Optimizing Performance of Equipment Fleets Under Dynamic Operating Conditions: Generalizable Shift Detection and Multimodal LLM-Assisted State Labeling

Abstract

1. Introduction

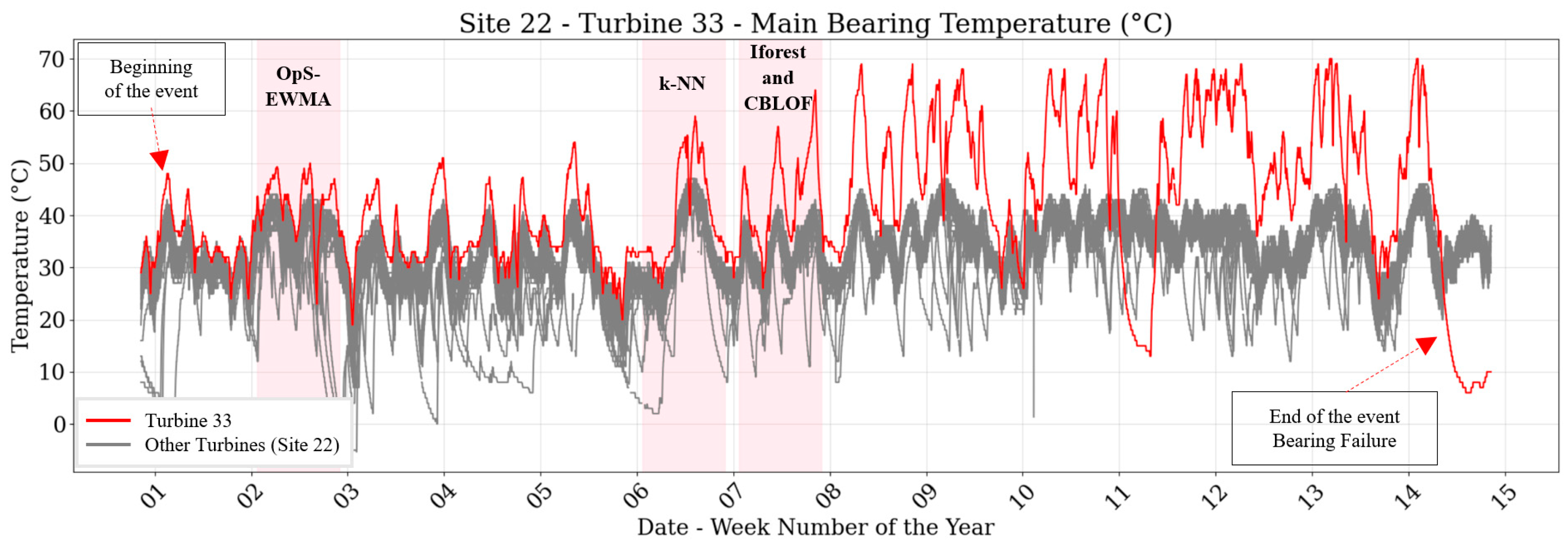

- Generalizable Shift Detection: We develop a residual EWMA-based method that can be uniformly applied to monitor any subset of similar components in a fleet. It automatically compensates for common external influences by referencing fleet averages, enabling detection of true performance degradation with minimal false alarms. The approach is lightweight and easily scalable to hundreds of sensors, since it avoids intensive model training or complex tuning per sensor.

- Criticality Scoring Mechanism: We propose a three-phase, prompt-driven LLM pipeline that integrates time-series data with domain-specific textual knowledge. Through retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), the LLM is grounded in technical documentation and produces contextualized explanations of anomalies, including likely causes and potential remedial actions. Building on this, we introduce a severity index, which combines a statistical anomaly score with a semantic score derived from LLM reasoning. Unlike traditional labeling approaches, this dual-scoring process provides interpretable criticality levels for each event. The result is a structured repository of diagnostic cases enriched with graded severity labels, enabling more effective search, retrieval, and knowledge transfer across the fleet.

- Applicability to Wind Energy: We validate our approach on a real-world case study using SCADA data from 1997 wind turbines across 41 wind farms, demonstrating interpretable results that can directly inform asset management decisions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Condition Monitoring and Predictive Maintenance

2.2. Anomaly Detection and Diagnostics with Generative AI

3. Methodology

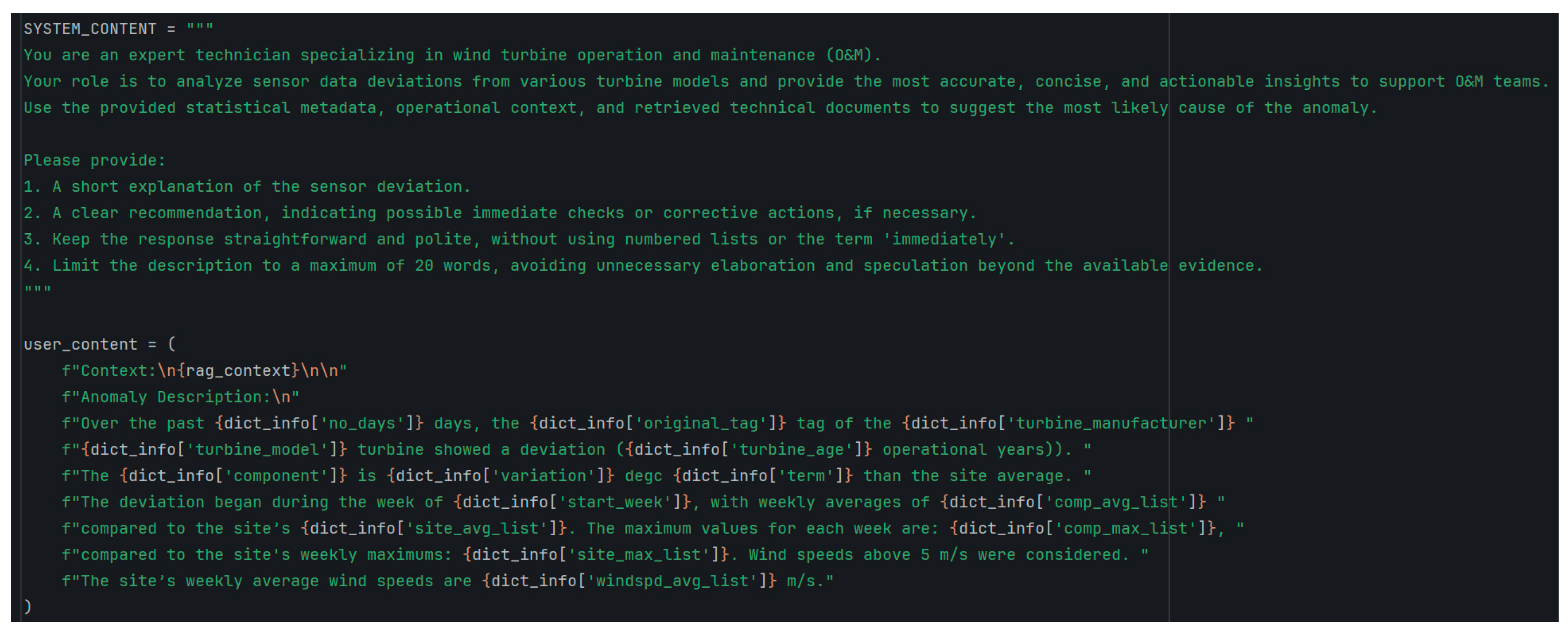

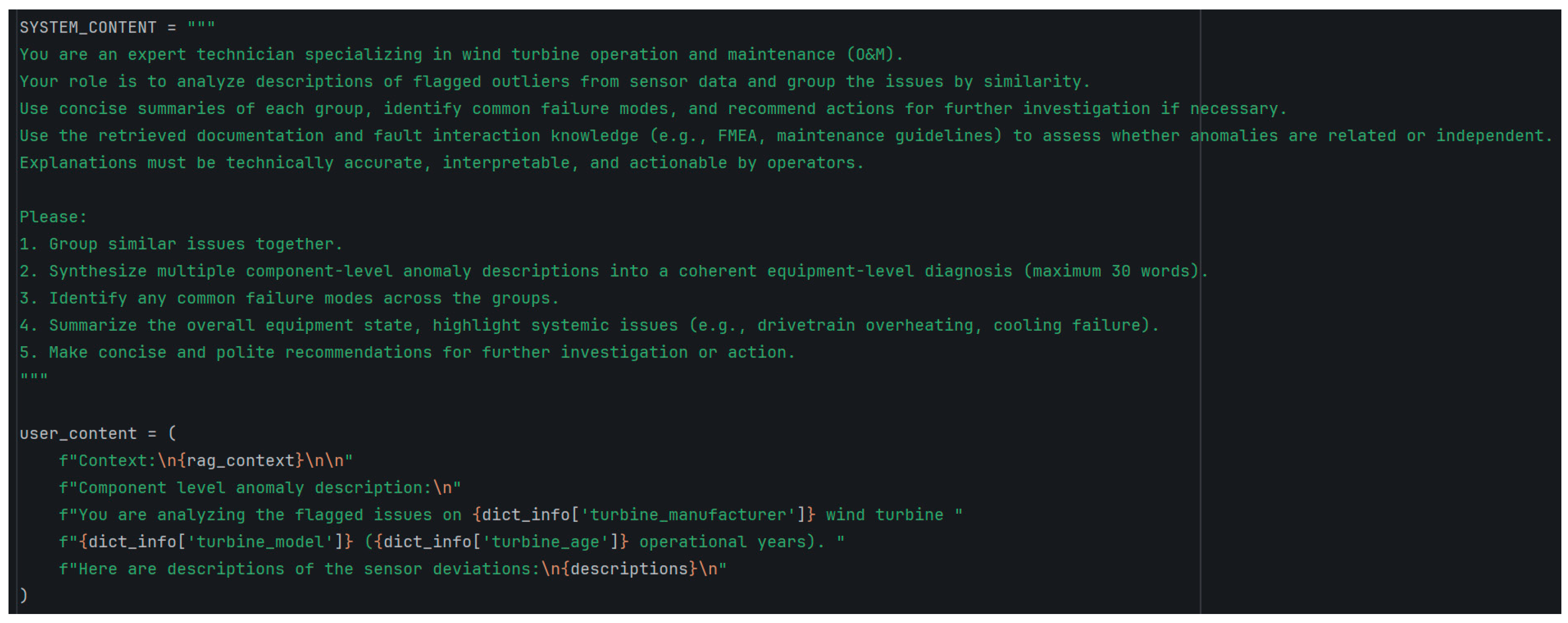

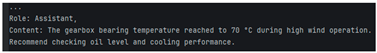

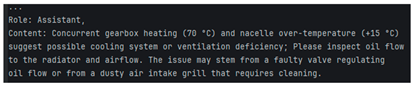

- Phase I—Component-Level Diagnosis: The system prompt establishes the role, and the user prompt supplies the event packet details (semantic summary a component’s anomaly). The prompt is enriched with RAG-retrieved domain knowledge (technical manuals, fault databases, maintenance records). The LLM then produces an initial diagnosis at the component level and possibly suggests immediate checks or actions.

- Phase II—Equipment-Level Synthesis: The user prompt in Phase II aggregates the outputs from Phase I along with any additional subsystem-level knowledge (e.g., equipment operation manuals or failure mode and effects analyses (FMEA)). The LLM performs reasoning across components to capture system-wide fault patterns, consistent with hierarchical fault modeling approaches reported in the literature [68].

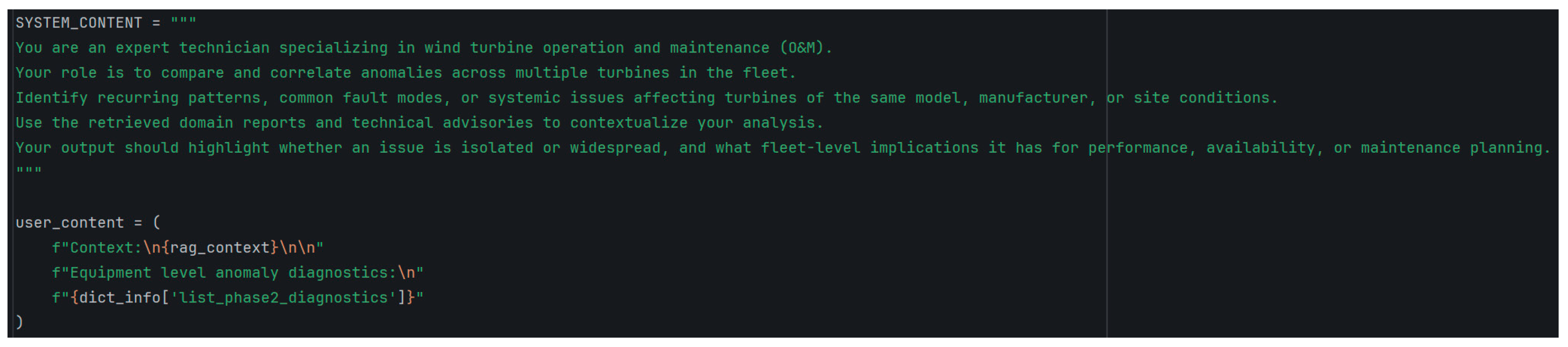

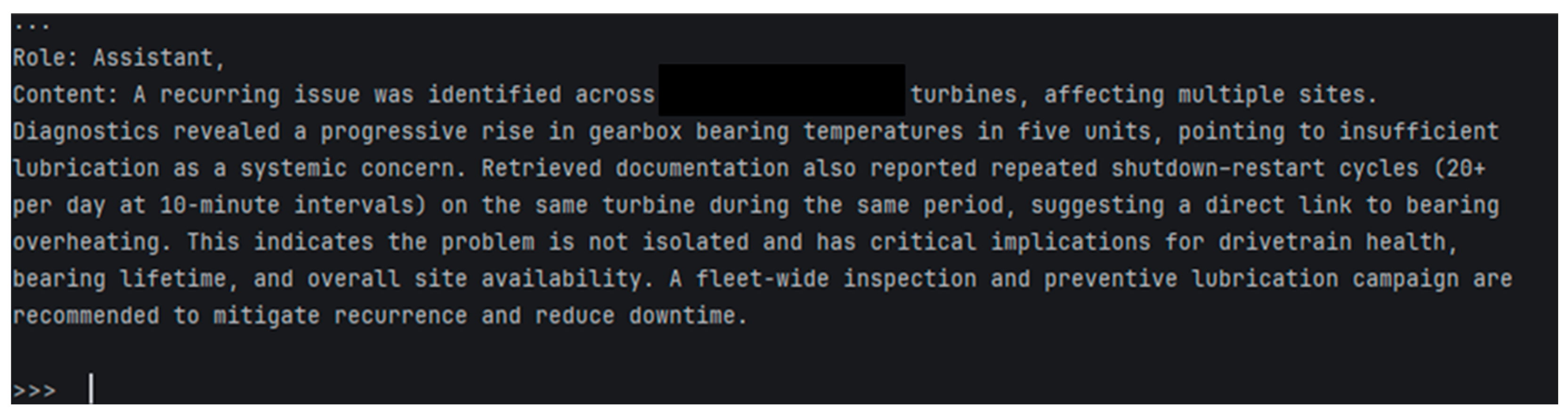

- Phase III (optional)—Fleet-Level Reasoning: Finally, the model generalizes across multiple units to detect fleet-wide trends, identify recurring anomalies, and distinguish isolated issues from systemic problems. This step leverages collective insights and aligns with research advocating fleet-level anomaly detection frameworks [69].

- The statistical score combines the standardized EWMA residual and the number of consecutive points beyond the control limit (). A larger deviation or longer run of out-of-control points yields a higher severity index. This captures the degree to which the sensor reading deviated from expected fleet behavior.where

- : set of components in normal state for equipment .

- : cardinality (number of elements) of the corresponding sets.

- : EWMA standardized residual statistics for component equipment at time .

- EWMA standardized residual statistic for component operating under extreme condition—maximum realistic operating temperature.

- : the number of consecutive points for component beyond the control limit.

- : total number of weeks within the analysed period, where is the observation horizon and is the resampling interval.

- , : weighting coefficients balancing the contribution of relative residual magnitude vs. control-limit violations.

- : aggregated residual ratio for equipment .

- : normalized run-length index for equipment .

- The semantic score is derived from the LLM’s output. Using a keyword ontology, if the explanation contains terms associated with severe faults or urgent action, the score increases. If the LLM cites historical failure cases or manufacturer’s warnings, additional weight is added.where

- : score for severity keywords (e.g., urgent fault descriptors).

- : score for historical cases and manufacturer warnings.

- : weight controlling the contribution of semantic evidence.

- Increasing (statistical severity) amplifies sensitivity to sharp, short-term deviations and may increase false positives in noisy environments;

- Increasing (duration/persistence) emphasizes slowly developing or long-duration faults but may reduce responsiveness to transient yet high-impact events;

- Increasing (semantic severity) strengthens reliance on LLM-informed contextual cues, improving interpretability but potentially propagating model bias if retrieval context is incomplete or not high-quality.

4. Case Study—Wind Power Plant

- The “rag_context”: is constructed using LangChain’s ingestion and retrieval pipeline. Documents (technical manuals, maintenance logs, and fault databases) are ingested with DirectoryLoader and split into manageable chunks using RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter. Each chunk is embedded into a dense vector representation with OpenAIEmbeddings, and the resulting embeddings are indexed in a FAISS vector store. At runtime, the anomaly description is converted into the same embedding space and used to query FAISS for the most relevant passages, which are then appended to the user prompt.

- The “dict_info” dictionary containing anomaly metadata: the number of days since detection (via OpS-EWMA), the original sensor tag, turbine manufacturer/model/age, component affected, and the variation compared to site averages. Weekly averages and maxima (component vs. site) and average wind speeds are also included (operating condition), aligned with the 7-day resampling used for the OpS-Matrix.

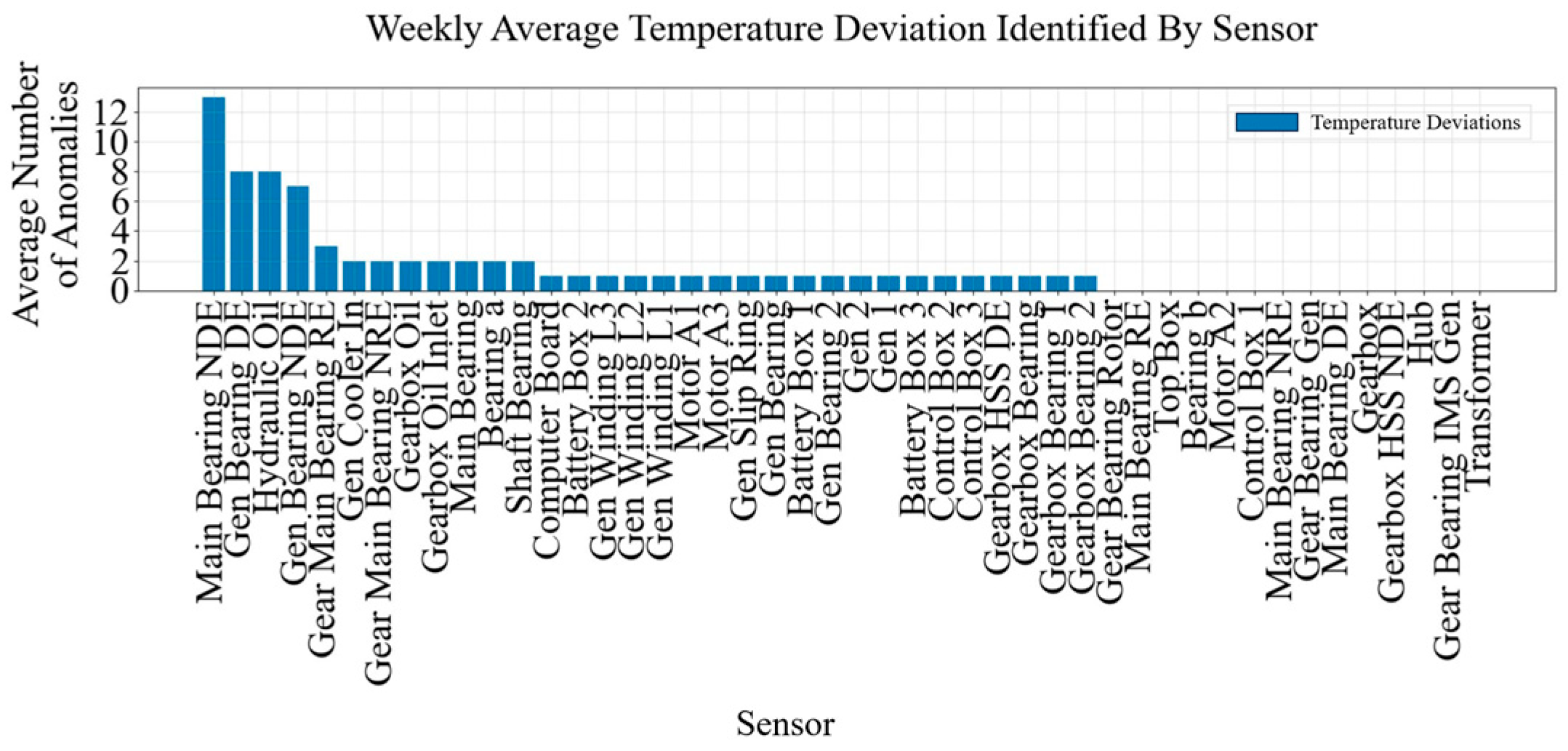

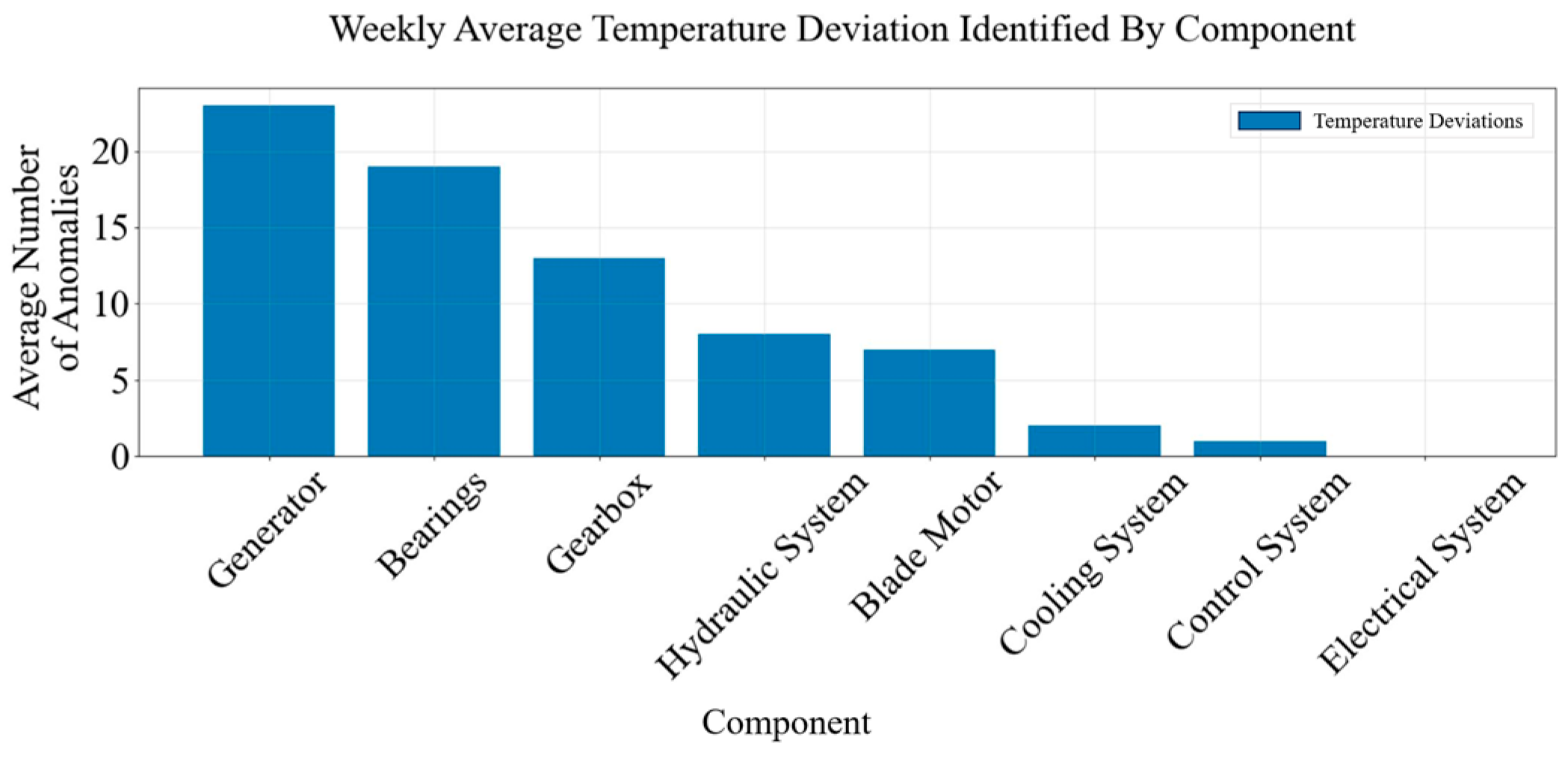

4.1. Equipment Level Diagnostics and Severity Factor Calculation

4.2. Fleet Level Diagnostics

4.3. Evaluation of Model Performance

- Accuracy: proportion of correct predictions (both normal and anomalous).

- Precision: proportion of detected anomalies that were true positives.

- Recall: proportion of true anomalies that were successfully detected.

- F1-score: harmonic mean of precision and recall, balancing both.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

- LLM Model: gpt-4-0613 (OpenAI), temperature = 0.3;

- Embedding Model: text-embedding-3-small (OpenAI);

- Vector Database: FAISS (local instance);

- Document Types Used: 7 turbine manuals; 104 monthly anomaly reports; fault investigation records for 10 sites;

- Total Documents Ingested: 121 primary documents (~3800 vector chunks);

- Document Loader: PyPDF2 for PDF manuals; text/CSV loader for reports;

- Chunking Strategy: Chunk size = 2000 chars; overlap = 200; maximum chunk size = 2500;

- Retrieval Settings: Top-K = 8; cosine similarity threshold = 0.2;

- Document Priority Weights: manuals = 1.0; anomaly database = 1.2; fault records = 0.8;

- Component-to-Document Mapping: Gearbox, generator, bearings, hydraulic, cooling, electrical, blade-pitch, and control systems mapped to corresponding manuals documents;

- Hardware Environment: Local workstation with a 12th Gen Intel® Core™ i9-12900H CPU (14 cores, 20 threads), embedding and processing on CPU; GPT-4 inference via API; optional GPU-accelerated retrieval using Intel Iris Xe Graphics + NVIDIA RTX A2000 8GB.

Appendix A.2

References

- Kaced, R.; Kouadri, A.; Baiche, K.; Bensmail, A. Multivariate nuisance alarm management in chemical processes. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2021, 72, 104548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Huang, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Su, B.; Dong, Z. Research on machine learning-based correlation analysis method for power equipment alarms. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Informatics, Networking and Computing (ICINC), Nanjing, China, 14–16 October 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirshahi, A.; Aliyari-Shoorehdeli, M. Diagnosing root causes of faults based on alarm flood classification using transfer entropy and multi-sensor fusion approaches. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 181, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, F.; Chen, T.; Shah, S.L. An Overview of Industrial Alarm Systems: Main Causes for Alarm Overloading, Research Status, and Open Problems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2016, 13, 1045–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucke, M.; Chioua, M.; Grimholt, C.; Hollender, M.; Thornhill, N.F. Integration of alarm design in fault detection and diagnosis through alarm-range normalization. Control. Eng. Pract. 2020, 98, 104388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucke, M.; Chioua, M.; Grimholt, C.; Hollender, M.; Thornhill, N.F. Advances in alarm data analysis with a practical application to online alarm flood classification. J. Process Control. 2019, 79, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, K.; Gallagher, C.; O’Donovan, P.; O’Sullivan, D.T.J. Cluster analysis of wind turbine alarms for characterising and classifying stoppages. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2018, 12, 1146–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevin, L.; Colm, G.; Peter, O.D.; Ken, B.; Dominic, T.J.O.S. A Robust Prescriptive Framework and Performance Metric for Diagnosing and Predicting Wind Turbine Faults Based on SCADA and Alarms Data with Case Study. Energies 2018, 11, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, A.; Khan, M.T.; Iqbal, J. A review on fault detection and diagnosis techniques: Basics and beyond. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2021, 54, 3639–3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Tian, X.; Liu, H.; Ma, L. Fault detection of networked dynamical systems: A survey of trends and techniques. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2021, 52, 3390–3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Zhang, W.; Samaran, J.; Savitha, R.; Foo, C.S. An Evaluation of Anomaly Detection and Diagnosis in Multivariate Time Series. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 33, 2508–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preciado-Grijalva, A.; Iza-Teran, V.R. Anomaly Detection of Wind Turbine Time Series using Variational Recurrent Autoencoders. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.02468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhou, H.; Cheng, L.; Xia, M. Condition Monitoring and Anomaly Detection of Wind Turbines Using Temporal Convolutional Informer and Robust Dynamic Mahalanobis Distance. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 3536914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, T. Anomaly Detection for Wind Turbines Using Long Short-Term Memory-Based Variational Autoencoder Wasserstein Generation Adversarial Network under Semi-Supervised Training. Energies 2023, 16, 7008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwetsloot, I.M.; Jones-Farmer, L.A.; Woodall, W.H. Monitoring univariate processes using control charts: Some practical issues and advice. Qual. Eng. 2024, 36, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugaz, W.; Sánchez, I.; Alonso, A.s.M. Adaptive EWMA control charts with time-varying smoothing parameter. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 93, 3847–3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, P.W.; Byun, Y.-C. A Review of machine learning techniques for wind turbine’s fault detection, diagnosis, and prognosis. Int. J. Green Energy 2024, 21, 771–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, G.; Li, X.; Wang, Q.; He, Y.; Yang, X. Wind turbine anomaly detection based on SCADA: A deep autoencoder enhanced by fault instances. ISA Trans. 2023, 139, 586–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allal, Z.; Noura, H.N.; Vernier, F.; Salman, O.; Chahine, K. Wind turbine fault detection and identification using a two-tier machine learning framework. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2024, 22, 200372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lei, Y.; Li, Y.; Parkinson, S.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Lu, F.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Yang, B.; et al. Large Models for Machine Monitoring and Fault Diagnostics: Opportunities, Challenges and Future Direction. J. Dyn. Monit. Diagn. 2025, 4, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Gao, X.; Jia, K.; Pan, J.; Bi, Y.; Dai, Y.; Sun, J.; Wang, M.; Wang, H. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Large Language Models: A Survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.10997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; He, Y. Intelligent Fault Diagnosis for CNC Through the Integration of Large Language Models and Domain Knowledge Graphs. Engineering 2025, 53, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabane, B.; Komljenovic, D.; Abdul-Nour, G. Optimizing Performance of Equipment Fleets in Dynamic Environments: A Straightforward Approach to Detecting Shifts in Component Operational States. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Energy Technologies, ICECET, Sydney, Australia, 25–27 July 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Tula, A.; Chen, X. From prompt design to iterative generation: Leveraging LLMs in PSE applications. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2025, 202, 109282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandemir, E.; Hasan, A.; Kvamsdal, T.; Abdel-Afou Alaliyat, S. Predictive digital twin for wind energy systems: A literature review. Energy Inform. 2024, 7, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Ren, S.; Jiang, H. Predictive maintenance of wind turbines based on digital twin technology. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 1344–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habbouche, H.; Amirat, Y.; Benbouzid, M. Leveraging Digital Twins and AI for Enhanced Gearbox Condition Monitoring in Wind Turbines: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, J.; Cui, Q.; Wen, J.; Fei, X. Digital twin-driven online intelligent assessment of wind turbine gearbox. Wind. Energy 2024, 27, 797–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon-Medina, J.X.; Tibaduiza, D.A.; Parés, N.; Pozo, F. Digital twin technology in wind turbine components: A review. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2025, 26, 200535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, D.; Xia, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Duan, J. Overview of predictive maintenance based on digital twin technology. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Pen, H.; Wang, Z.; Chang, C.S. Feature Knowledge Based Fault Detection of Induction Motors Through the Analysis of Stator Current Data. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2016, 65, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgoshaei, P.; Delgoshaei, P.; Austin, M. Framework for Knowledge-Based Fault Detection and Diagnostics in Multi-Domain Systems: Application to HVAC Systems; Institute for Systems Research: College Park, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Zhu, X.; Xue, T.; Zhang, L. An overview of recent advances in model-based event-triggered fault detection and estimation. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2023, 54, 929–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isermann, R. Model-based fault-detection and diagnosis—Status and applications. Annu. Rev. Control 2005, 29, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jieyang, P.; Kimmig, A.; Dongkun, W.; Niu, Z.; Zhi, F.; Jiahai, W.; Liu, X.; Ovtcharova, J. A systematic review of data-driven approaches to fault diagnosis and early warning. J. Intell. Manuf. 2023, 34, 3277–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yang, Y. Data-Driven Optimal Distributed Fault Detection Based on Subspace Identification for Large-Scale Interconnected Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 2497–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, K.; Sayed Mouchaweh, M.; Cornez, L. Fault Prognostics for the Predictive Maintenance of Wind Turbines: State of the Art. In ECML PKDD 2018 Workshops; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Dagnino, A.; Ding, Y. Unsupervised Anomaly Detection Based on Minimum Spanning Tree Approximated Distance Measures and Its Application to Hydropower Turbines. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2019, 16, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Pan, J.; Xi, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, J. Vibration anomaly detection of wind turbine based on temporal convolutional network and support vector data description. Eng. Struct. 2024, 306, 117848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eugenio, B.; Luca, C.; Cristiana, D.; Luigi Gianpio Di, M. Explainable AI for Machine Fault Diagnosis: Understanding Features’ Contribution in Machine Learning Models for Industrial Condition Monitoring. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Liliang, W.; Feng, L.; Zheng, Q. Clustering Analysis of Wind Turbine Alarm Sequences Based on Domain Knowledge-Fused Word2vec. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.; Jahangir, Z.; Riaz, M.B.; Saeed, M.J.; Sattar, M.A. Industrial applications of large language models. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximilian, L. A Text-Based Predictive Maintenance Approach for Facility Management Requests Utilizing Association Rule Mining and Large Language Models. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2024, 6, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, G.; Cecchi, G.; Rizzo, A. Large Language Models for Predictive Maintenance in the Leather Tanning Industry: Multimodal Anomaly Detection in Compressors. Electronics 2025, 14, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Atarashi, K.; Takeuchi, K.; Kashima, H. Emulating Retrieval Augmented Generation via Prompt Engineering for Enhanced Long Context Comprehension in LLMs. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.12462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaif, K.M.; Albeshri, A.A.; Khemakhem, M.A.; Eassa, F.E. Multimodal Large Language Model-Based Fault Detection and Diagnosis in Context of Industry 4.0. Electronics 2024, 13, 4912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecklenburg, N.; Lin, Y.; Li, X.; Holstein, D.; Nunes, L.; Malvar, S.; Silva, B.; Chandra, R.; Aski, V.; Yannam, P.K.R.; et al. Injecting New Knowledge into Large Language Models via Supervised Fine-Tuning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.00213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia Álvaro, J.A.; Barreda, J.G. An advanced retrieval-augmented generation system for manufacturing quality control. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 64, 103007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xu, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Luo, H.; Wang, Y.; Gui, W. Labeling-free RAG-enhanced LLM for intelligent fault diagnosis via reinforcement learning. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2026, 69, 103864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Tang, X.; Gu, S.; Cui, L. An intelligent guided troubleshooting method for aircraft based on HybirdRAG. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell-Gilbert, A.; Mittal, S.; Rahimi, S.; Seale, M.; Jabour, J.; Arnold, T.; Church, J. RAAD-LLM: Adaptive Anomaly Detection Using LLMs and RAG Integration. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.02800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Wen, Q.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Xue, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, X.; et al. Large Models for Time Series and Spatio-Temporal Data: A Survey and Outlook. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.10196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Wang, S.; Ma, L.; Chu, Z.; Zhang, J.Y.; Shi, X.; Chen, P.-Y.; Liang, Y.; Li, Y.-F.; Pan, S.; et al. Time-LLM: Time Series Forecasting by Reprogramming Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.01728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.F.; Stella, L.; Turkmen, C.; Zhang, X.; Mercado, P.; Shen, H.; Shchur, O.; Rangapuram, S.S.; Arango, S.P.; Kapoor, S.; et al. Chronos: Learning the Language of Time Series. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.07815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Niu, P.; Wang, X.; Sun, L.; Jin, R. One Fits All:Power General Time Series Analysis by Pretrained LM. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.11939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Hong, S. TEST: Text Prototype Aligned Embedding to Activate LLM’s Ability for Time Series. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.08241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabane, B.; Komljenovic, D.; Abdul-Nour, G. Converging on human-centred industry, resilient processes, and sustainable outcomes in asset management frameworks. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2023, 43, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrou, F.; Bouyeddou, B.; Sun, Y. Sensor Fault Detection in Wind Turbines Using Machine Learning and Statistical Monitoring Chart. In Proceedings of the 2023 Prognostics and Health Management Conference (PHM), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 28 October–2 November 2023; pp. 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haridy, S.; Wu, Z. Univariate and multivariate control charts for monitoring dynamic-behavior processes: A case study. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2009, 2, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartkopf, J.P.; Reh, L. Challenging golden standards in EWMA smoothing parameter calibration based on realized covariance measures. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 56, 104129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areepong, Y.; Chananet, C. Optimal parameters of EWMA Control Chart for Seasonal and Non-Seasonal Moving Average Processes. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2014, 012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, J.M.; Saccucci, M.S. Exponentially Weighted Moving Average Control Schemes: Properties and Enhancements. Technometrics 1990, 32, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.A.; Champ, C.W.; Rigdon, S.E. The Performance of Exponentially Weighted Moving Average Charts With Estimated Parameters. Technometrics 2001, 43, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrou, F.; Sun, Y.; Hering, A.S.; Madakyaru, M.; Dairi, A. Statistical Process Monitoring Using Advanced Data-Driven and Deep Learning Approaches: Theory and Practical Applications; Elsevier: San Diego, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cambron, P.; Tahan, A.; Masson, C.; Pelletier, F. Bearing temperature monitoring of a Wind Turbine using physics-based model. J. Qual. Maint. Eng. 2017, 23, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrou, F.; Sun, Y.; Dorbane, A.; Bouyeddou, B. Sensor fault detection in photovoltaic systems using ensemble learning-based statistical monitoring chart. In Proceedings of the 2023 11th International Conference on Smart Grid (icSmartGrid), Paris, France, 4–7 June 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambron, P.; Masson, C.; Tahan, A.; Pelletier, F. Control chart monitoring of wind turbine generators using the statistical inertia of a wind farm average. Renew. Energy 2018, 116, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhada, M.; Girolami, M.; Parlikad, A.K. Anomaly detection in a fleet of industrial assets with hierarchical statistical modeling. Data-Centric Eng. 2020, 1, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickx, K.; Meert, W.; Mollet, Y.; Gyselinck, J.; Cornelis, B.; Gryllias, K.; Davis, J. A general anomaly detection framework for fleet-based condition monitoring of machines. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 139, 106585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guezuraga, B.; Zauner, R.; Pölz, W. Life cycle assessment of two different 2 MW class wind turbines. Renew. Energy 2012, 37, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plumley, C.; Takeuchi, R. Penmanshiel wind farm data (Version v3). Zenodo 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plumley, C.; Takeuchi, R. Kelmarsh wind farm data (Version v4). Zenodo 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Detection Core Mechanism | LLM Reasoning + Knowledge Integration | Outputs + Scale of Applicability | Distinctive Features/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical SPC-based methods (Shewhart, CUSUM, EWMA, PCA–T2) | Univariate/multivariate control charts | None (no LLM; no RAG/KG) | Binary control-limit breach per variable; limited to equipment-level monitoring | Interpretable, lightweight; no diagnostics |

| ML/DL anomaly detectors (autoencoders, LSTM–VAE, TCN, GAN, etc.) | Data-driven anomaly scoring/reconstruction-error–based detection | None (no LLM; no RAG/KG) | Anomaly score or binary label; limited generalizability across heterogeneous fleets | High accuracy but requires training; black-box |

| RAG-enhanced LLM diagnostic assistants (RAG-GPT, HybridRAG, LLM + KG frameworks) | External detector (rule-based, ML or alarms) | LLM explanations grounded via RAG or KG | Free-text diagnostic narratives; asset or plant-level rather than fleet-wide | Good explanations; weak detection integration |

| AAD-LLM/RAAD-LLM frameworks (SPC + feature extraction + LLM) | SPC statistics + DFT features | RAG injects historical thresholds or statistical references; LLM acts as classifier | Binary anomaly decision per sensor window; limited multi-asset generalization | Adaptive baseline updates; no semantic scoring |

| Proposed OpS-EWMA-LLM | Residual EWMA on fleet baselines producing OpS-Matrix | Hierarchical multi-phase LLM reasoning enriched with RAG technical documents | Structured operational state labels (Normal/Warning/Critical) with fleet-wide applicability | Hybrid pipeline: statistical rigor + semantic reasoning + dual scoring |

| Model Categories | Description | Strengths | Limitation | Paper |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge-Based Methods | Use expert knowledge to identify potential faults. Examples include rule-based systems, expert systems, and fuzzy logic. | Leverage domain expertise to make accurate predictions even with relatively little data. | Rely heavily on the availability and quality of expert knowledge, which may not be available or may be expensive to acquire. Also, these methods might not adapt well to new or changing conditions that weren’t anticipated by the experts. | [31,32] |

| Model-Based Methods | Rely on mathematical models that describe the physical behavior of the system. Examples include physics-based models, fault trees, and reliability models. | Very accurate when the model correctly describes the system, and they can also provide insight into the underlying physical processes. | The accuracy of these methods is heavily dependent on the accuracy of the model. Building accurate models can be challenging, especially for complex and nonlinear systems. These methods can also be computationally intensive. | [33,34] |

| Data-Driven Methods | Rely on historical data to identify patterns or anomalies that might indicate a fault. Examples include statistical methods, machine learning, and deep learning. | Handle complex, nonlinear systems, and they can potentially discover unexpected patterns or faults. | Require large amounts of high-quality, labeled data, which can be difficult to obtain, particularly for rare faults. Also, many data-driven methods (like deep learning) are “black box” models that can be difficult to interpret. | [35,36] |

| Prompt Elements | Phase I | Phase II | Phase III |

|---|---|---|---|

| System | Assigns the role of component-level diagnostic assistant. | Defines the role as equipment-level synthesizer. | Defines the role as fleet-level analyst. |

| User | Contains the anomaly event packet for a single component. | Aggregates all component-level diagnoses for one piece of equipment. | Collects all equipment-level summaries across the fleet. |

| Contextual Data | Retrieves relevant manuals, fault databases, and maintenance logs related to that component/anomaly. | Retrieves subsystem interaction models, equipment manuals, and FMEA reports. | Retrieves fleet bulletins, cross-site maintenance reports, and industry alerts. |

| Assistance | Initial diagnosis for the component; may suggest immediate checks or corrective actions. | Integrated diagnosis of the equipment state; identifies subsystem interactions and higher-level fault patterns. | Comparative reasoning across units; detects systemic issues, recurring anomalies, or fleet-wide trends. |

| Category | Keywords | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Urgent action required | “immediate action”, “urgent repair”, “danger”, “alarm flood”, “out of service” | +1/2 |

| Critical fault | “failure”, “breakdown”, “shutdown”, “trip”, “overheating”, “critical fault”, “unsafe operation”, “abnormal condition” | +1/3 |

| Warning | “degradation”, “reduced efficiency”, “unusual vibration”, “abnormal trend”, “early warning” | +1/6 |

| Category | Keywords | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer warnings | “OEM alert”, “manufacturer’s bulletin”, “safety notice”, “technical advisory” | +1/2 |

| Historical failures | “previous incident”, “recurrence”, “historical failure mode”, “documented case” | +1/3 |

| Best-practice reference | “standard procedure”, “maintenance guideline”, “compliance issue” | +1/6 |

| Phase I—Component Level Analysis Output | Phase II—Equipment Level Diagnostics |

|---|---|

1.  2.  |  |

| Metrics | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-NN | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.72 | 0.77 |

| IForest | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.74 | 0.81 |

| CBLOF | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.83 |

| OpS-EWMA | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.83 | 0.88 |

| OpS-EWMA-LLM | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chabane, B.; Abdul-Nour, G.; Komljenovic, D. Optimizing Performance of Equipment Fleets Under Dynamic Operating Conditions: Generalizable Shift Detection and Multimodal LLM-Assisted State Labeling. Sustainability 2026, 18, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010132

Chabane B, Abdul-Nour G, Komljenovic D. Optimizing Performance of Equipment Fleets Under Dynamic Operating Conditions: Generalizable Shift Detection and Multimodal LLM-Assisted State Labeling. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010132

Chicago/Turabian StyleChabane, Bilal, Georges Abdul-Nour, and Dragan Komljenovic. 2026. "Optimizing Performance of Equipment Fleets Under Dynamic Operating Conditions: Generalizable Shift Detection and Multimodal LLM-Assisted State Labeling" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010132

APA StyleChabane, B., Abdul-Nour, G., & Komljenovic, D. (2026). Optimizing Performance of Equipment Fleets Under Dynamic Operating Conditions: Generalizable Shift Detection and Multimodal LLM-Assisted State Labeling. Sustainability, 18(1), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010132