1. Introduction

With urban dwellers spending nearly 90% of their time indoors, the World Health Organization (WHO) has advocated since 2018 for buildings and designed interiors that foster physical, mental, and social well-being [

1,

2,

3]. Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) has become a vital metric in the past decades for human comfort, encompassing thermal, air, acoustic, and visual elements [

4,

5,

6]. A sustainable approach to enhancing IEQ entails the deployment of advanced building materials designed to prioritise a holistic well-being [

7]. In this context, passive materials have attracted research attention for their capacity to regulate indoor conditions such moisture, condensation, and CO

2 levels, offering an energy conscious approach to creating healthier indoor spaces [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Concurrently, Additive Manufacturing (AM) has emerged as a key technology for advancing these kinds of functional materials by enabling precise control over their porous structure and properties. Architected sorbents employing AM have recently attracted significant interest due to their advantages, such as reduced pressure drop and faster mass transfer, when compared to their conventionally shaped counterparts [

13,

14,

15,

16].

The literature on LCA of 3D-printed building components for passive strategies mainly focuses on the building level [

17,

18], with little attention to the production stage of individual components and in most studies focusing on concrete as the primary feedstock [

19,

20]. When looking into sorptive materials, while previous studies have explored the functional properties of 3D-printed ceramics for IEQ applications (e.g., natural cooling mechanisms based on terracotta clay TPMS geometries, 3D-printed clay components for passive indoor moisture buffering, 3D-printed Zeolite monoliths for CO

2 removal from enclosed environments) [

9,

21,

22], to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no prior research has investigated the development of multi-functional materials for indoor applications based on LDM processes that simultaneously consider a comprehensive evaluation of their environmental footprint. Currently, the literature on LCA of 3D-printed ceramics is very limited, with most studies primarily focusing on structural performance, rather than the environmental impacts [

23,

24,

25,

26]. While the work by Posani et al. [

27] sets a promising foundation in this context, the study only addresses Global Warming Potential (GWP) expressed in CO

2 eq and does not provide any insights or interpretation of results concerning other environmental impact categories, like resource depletion. Best practices in LCA emphasise the inclusion of multiple midpoint indicators to fully capture the range of potential environmental burdens. Overreliance on carbon metrics alone risks missing key trade-offs and unintended consequences that may arise in other dimensions of sustainability. Although the Posani et al. study [

27] provides information on the system boundaries of the analysis and on the Life Cycle Inventories (LCIs) used, the correlations between the LCI data, the LCA stages, and the LCA results remain unclear, implying the need for clarity and an explanatory description of the workflow and the LCA methodology followed. In addition, the LCIs used do not provide analytical data regarding electricity demands; instead, they rely on literature data rather than real data regarding electricity consumption. Therefore, consistency issues of proxies in terms of equipment, operation, electricity grid mix, etc., may arise, limiting the validity of data and the accuracy of results. The present research study addresses the lack of literature in the field by providing LCIs for 3D-printed ceramic components throughout their production stage, based on real measured data, while also ensuring transparency in the LCA methodology to support future studies.

The scope of the present study is twofold: (a) to investigate the materials and fabrication selection criteria for 3D-printed aluminosilicate components aimed for passive cooling and CO

2 adsorption in indoor conditions and (b) to evaluate the environmental impacts across the selected components’ production stage through Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), with a special focus on climate change mitigation. The dual-function components are fabricated using Liquid Deposition Modelling (LDM), an AM technology based on customised slurry-based feedstock materials. LDM was selected for the present study because the rheological properties and composition of the feedstock material, as well as the targeted component geometries, aligned closely with the operational requirements of slurry-based extrusion. Although other AM approaches, such as Stereolithography (SL), Inkjet Printing (IJP), or Direct Ink Writing (DIW), are capable of processing ceramic materials [

23], they were not pursued here, as no comparative evaluation was within the scope of this work. Furthermore, related studies have shown that LDM is a robust and reliable technique for producing ceramic slurry-based components, especially in interior architectural applications where scalability, geometric adaptability, and material customisation are critical advantages [

28].

To assess the environmental effects of the production process, the study employs the LCA methodology, an internationally standardised framework used to quantify potential environmental impacts across the product’s life cycle [

29,

30]. By introducing an integrative LDM design strategy, this study outlines a systematic approach to selecting materials and fabrication processes, considering the following:

- (a)

The functional performance requirements (i.e., humidity and CO2 adsorption capacity);

- (b)

The use of locally sourced materials (e.g., Zeolite minerals) in custom feedstock pastes;

- (c)

The constraints (e.g., dimensional accuracy) of the selected fabrication methods.

It should be noted that the functional performance requirements analysis—from point (a)—is beyond the scope of the present study and is addressed in a separate investigation within the EU-funded research ecosystem of iclimabuilt [

31].

The fabrication process is evaluated for its efficiency in material and energy use, as well as waste production. Additionally, post-processing is assessed for energy-saving opportunities, with particular attention paid to the potential of Low-Temperature Firing (LTF).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design Methodology

The study presents a computationally driven design approach for differential growth pattern generation [

32] and an interlocking assembly logic for modular systems. The software employed is the integrated visual programming platform Grasshopper [

33] of Rhinoceros 3D v. 7 [

34] in conjunction with the Kangaroo plugin [

35].

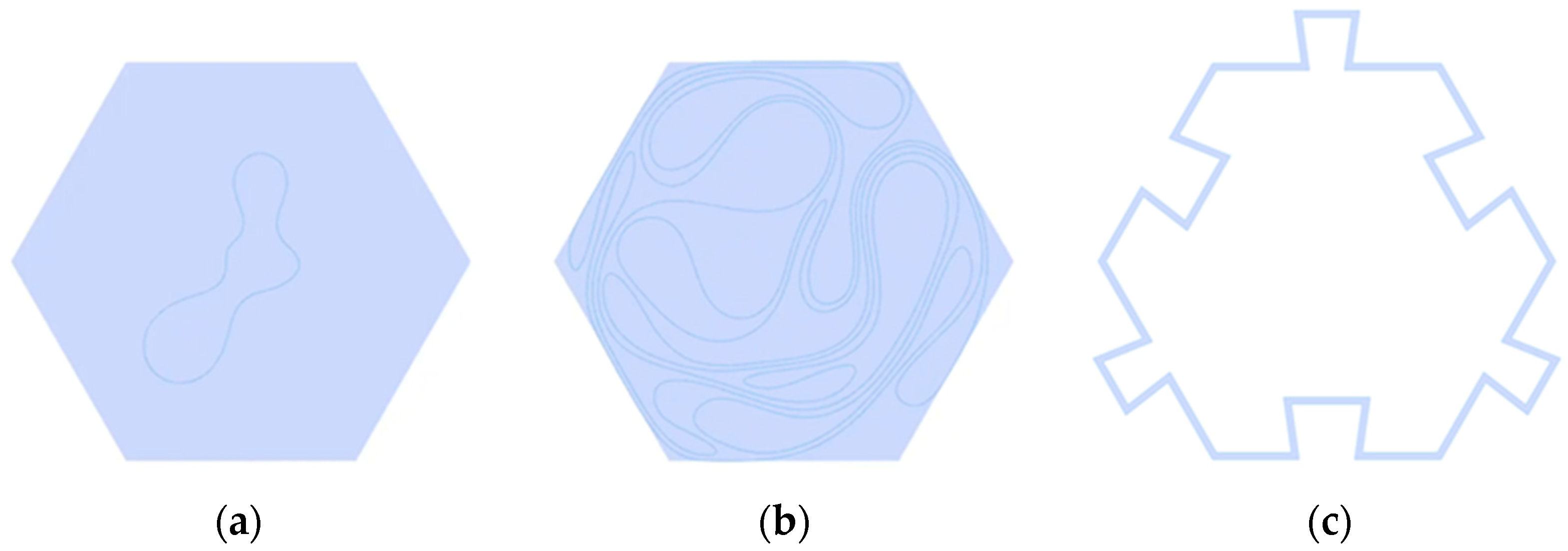

Differential growth emulates the natural expansion of curves within a constrained domain, resulting in complex, organic morphologies (

Figure 1a,b) that significantly increase exposed surface area while maintaining recessed features to enhance air circulation.

A puzzle-like assembly method (

Figure 1c) using blank and tab joints offers a versatile and scalable construction method. These interlocking joints allow components to fit together securely without the need for adhesives or fasteners, enabling quick and easy assembly or disassembly. This modular approach (

Figure 2) facilitates adaptive expansion, supporting customisable layouts in which elements can be added, removed, or rearranged according to the design requirements in terms of performance and aesthetics. The approach was selected for its simplicity, structural integrity, and applicability to a range of use cases, including space dividers or architectural facades.

2.2. Materials’ Selection Criteria and Formulation Methodology

Material selection was guided by a hierarchy of criteria, emphasising functionality, environmental impact, and manufacturing feasibility:

Table 1.

Weight Loss (%) and Diameter Change Δd (mm) in manually extruded BW10:5, KW10:5, and ZW10:5. Background colour indicates the selected materials.

Table 1.

Weight Loss (%) and Diameter Change Δd (mm) in manually extruded BW10:5, KW10:5, and ZW10:5. Background colour indicates the selected materials.

| Composition | Weight Loss (%) | Diameter Change Δd (mm) |

|---|

| BW10:5 | 51.6 | 3.90 ± 0.18 |

| KW10:5 | 27.1 | 0.90 ± 0.04 |

| ZW10:5 | 26.3 | 0.67 ± 0.07 |

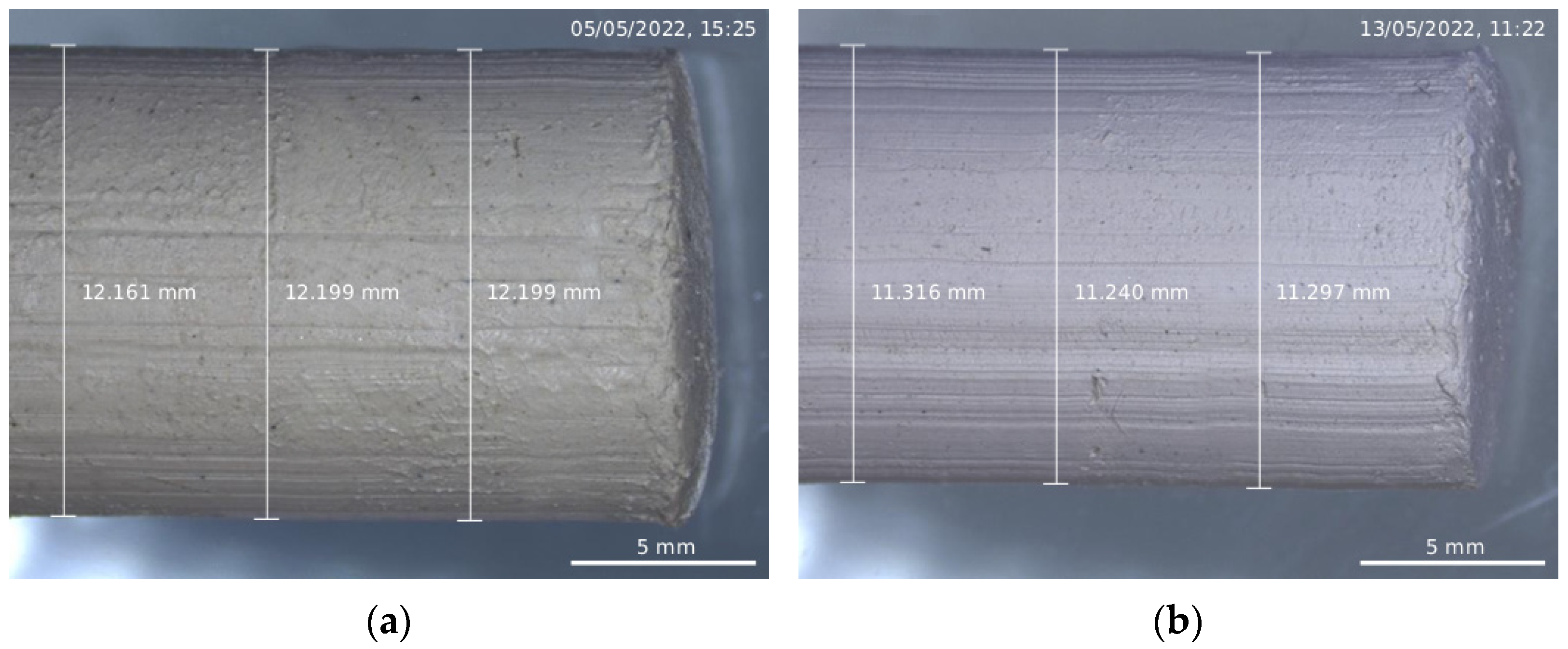

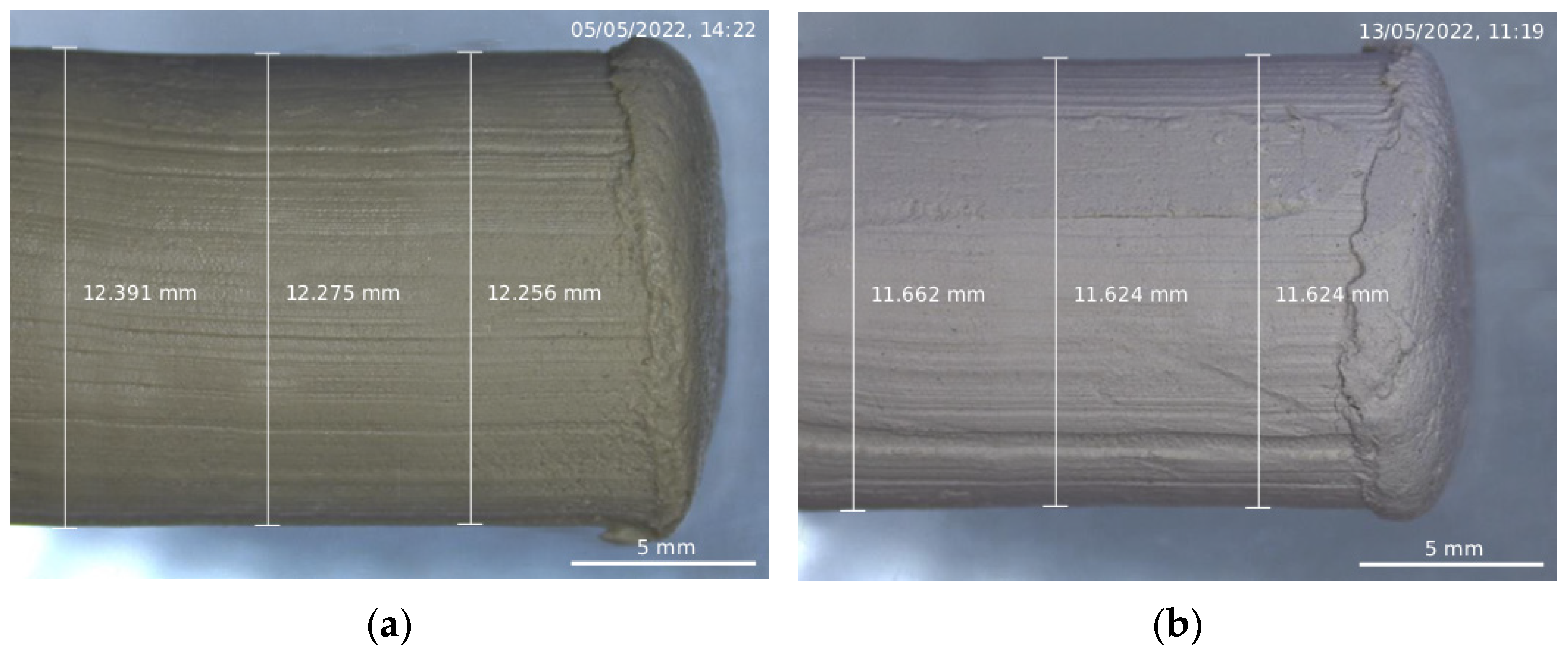

Figure 3.

Monitoring of manually extruded KW10:5 specimens: (a) humid and (b) dried after >7 days.

Figure 3.

Monitoring of manually extruded KW10:5 specimens: (a) humid and (b) dried after >7 days.

Figure 4.

Monitoring of manually extruded ZW10:5 specimens: (a) humid and (b) dried after >7 days.

Figure 4.

Monitoring of manually extruded ZW10:5 specimens: (a) humid and (b) dried after >7 days.

Table 2.

Weight Loss (%) in manually extruded ΖΚW7:3:5, ΖΚW8:2:5, and ΖΚW9:1:5. Background colour indicates the selected material formulation ratio.

Table 2.

Weight Loss (%) in manually extruded ΖΚW7:3:5, ΖΚW8:2:5, and ΖΚW9:1:5. Background colour indicates the selected material formulation ratio.

| Composition | Weight Loss (%) |

|---|

| ΖΚW7:3:5 | 27.3 |

| ΖΚW8:2:5 | 26.0 |

| ΖΚW9:1:5 | 25.6 |

The multi-criteria approach integrates sustainability with material performance and digital fabrication constraints.

2.3. Liquid Deposition Modelling (LDM) and Feedstock Material Design Parameters

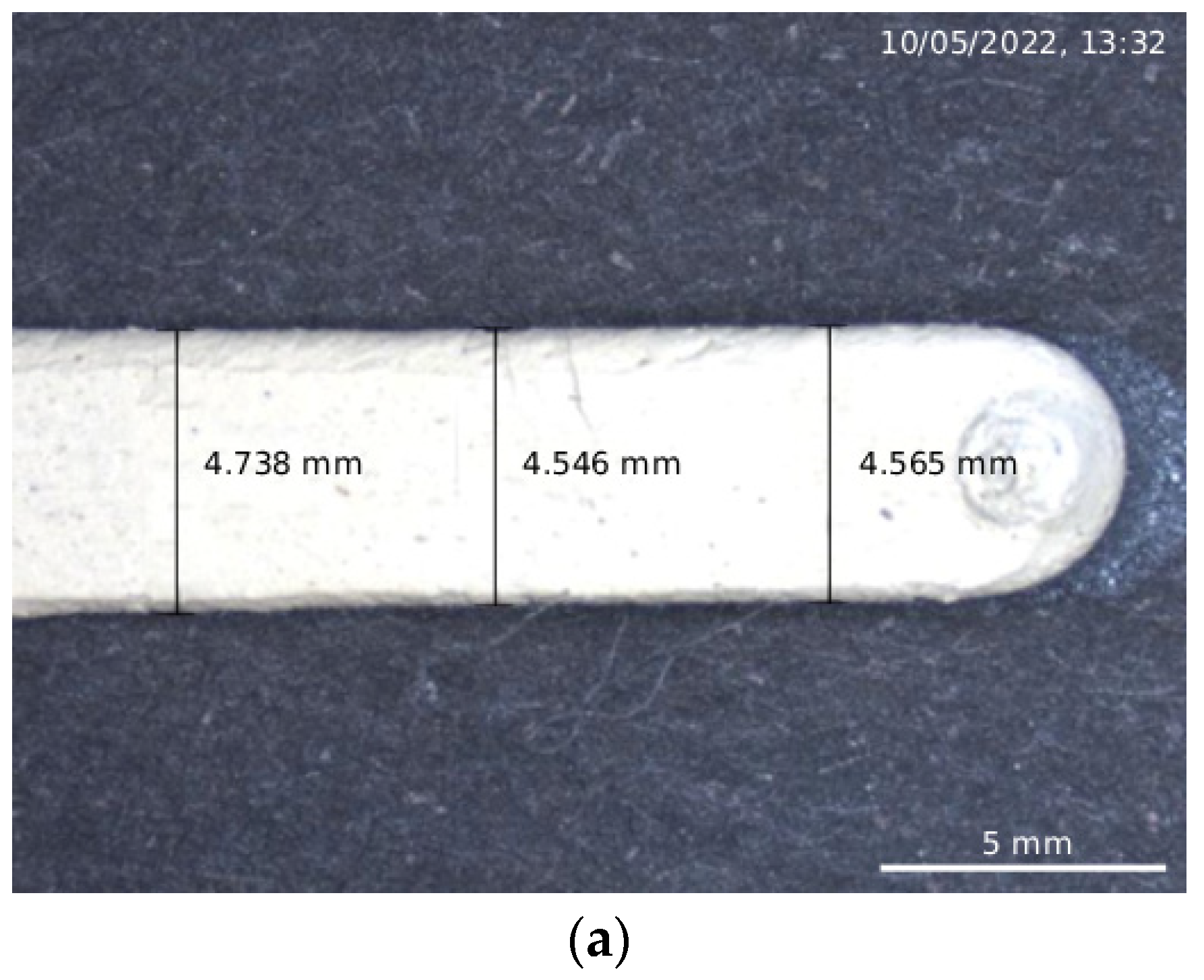

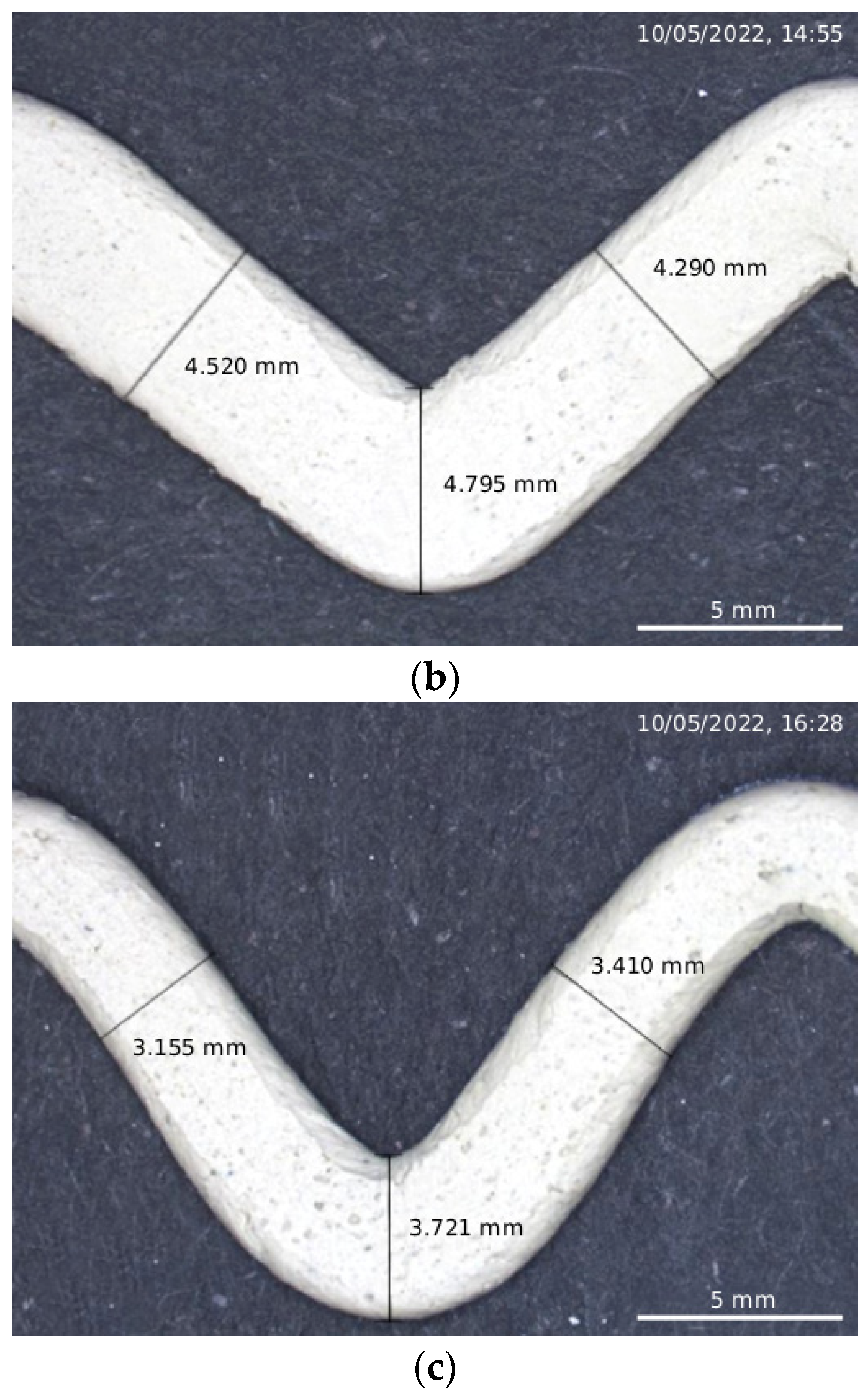

The manufacturing process was based on Liquid Deposition Modelling (LDM), a non-thermally extrusion-based AM technology, in which the feedstock material is employed in the form of paste. As discussed in

Section 1, LDM was selected for the present study because the feedstock’s rheological properties and composition, together with the intended component geometries, were well aligned with the requirements of slurry-based extrusion, particularly for interior architectural applications where advantages arise from the technology’s inherent scalability, geometric versatility, and material customisation potential. The development of feedstock material lies in manual or mechanical mixing of dry powder-based materials with a liquid medium (i.e., water). For the purposes of the present study, the ceramic 3D-printer WASP 40100 LDM (print volume capacity: ⌀400 mm × H1000 mm; selected nozzle resolution: ⌀3 mm; selected printing speed 15 mm/s, material extrusion pressure 5 bar) (WASP S.r.l., Massa Lombarda, RA, Italy) for fluid-dense materials was utilised. For the feedstock material, OLYMPUS Zeolite, PROLAT Kaolin, and deionised water were employed. The mixing was manually carried out by gradually adding deionised water to an initial quantity of powder until a homogenised result and the desired paste fluidity were achieved. While all previous material formulations (discussed in

Section 2.2) were tested in terms of manual extrudability and functional performance, only the selected formulation (i.e., ΖΚW

9:1:5) satisfying all the former criteria underwent printability assessment to ensure it could accommodate dimensional accuracy in the (a) linear (d

median = 4.616 mm,

s ≈ 0.1058 mm), (b) angular (d

median = 4.535 mm,

s ≈ 0.2528 mm), and (c) curved (d

median = 3.429 mm,

s ≈ 0.2834 mm) geometric features embedded in the design (

Figure 5). The aim was to maintain consistent layer width, particularly at points of geometric deviation, throughout the printing process. Negligible dimensional shrinkage was observed in curved toolpaths (

Figure 5c).

To validate the integration of the single-layer geometric features in the three-dimensional space—without material collapse during printing—two 3D hexagonal specimens (side length = 53 mm, height = 30 mm) (

Figure 6) were fabricated, as a proof of concept.

Finally, based on the feedstock material design parameters established and the concept design strategy outlined in

Section 2.1, preliminary ZKW

9:1:5 components (height = 3 mm) were fabricated and subjected to the post-processing and firing conditions detailed in

Section 2.4.

2.4. Post-Processing: Firing

After the 3D-printing process, the deposited layers were solidified through vaporisation of the liquid medium in indoor conditions (20–30 °C, relative humidity 40–60%). ΖΚW

9:1:5 specimens underwent thermal treatment for conditioning (105 °C for 3 h) and enhancement of mechanical properties under High-Temperature Firing (HTF) and Low-Temperature Firing (LTF) Protocol: (a) HTF, 400 °C for 2 h followed by 800 °C for 2 h, and (b) LTF, 400 °C for 4 h, with a ramp rate of 5 °C/min (

Figure 7).

2.5. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)

LCA is a comprehensive and systematic approach used to evaluate the potential environmental impacts of a product, process, or service, across its life cycle. This study performs the LCA methodology, as outlined in the internationally recognised standards ISO 14040:2006 [

29] and ISO 14044:2006 [

30], following the four basic LCA phases: (1) Goal and Scope Definition, (2) Inventory Analysis, (3) Impact Assessment, and the Interpretation of the LCA Results, which are presented in

Section 3. In this study, the LCA methodology is applied to the production stage of the 3D-printed dual-functionality ZKW

9:1:5 component, developed by BIOG3D.

2.5.1. Goal and Scope Definition

The primary goal of using LCA in this study is to assess the potential environmental impacts of the specific ZKW9:1:5 component and to identify any environmental hotspots across its manufacturing stage, with the final aim of climate change mitigation, towards product environmental sustainability. This analysis aims to identify opportunities for improving environmental performance, as well as to facilitate the design of more sustainable 3D-printed ceramic products. Furthermore, the research findings may inform both industry stakeholders and decision-makers in product redesign or development strategies aimed at reducing environmental impacts.

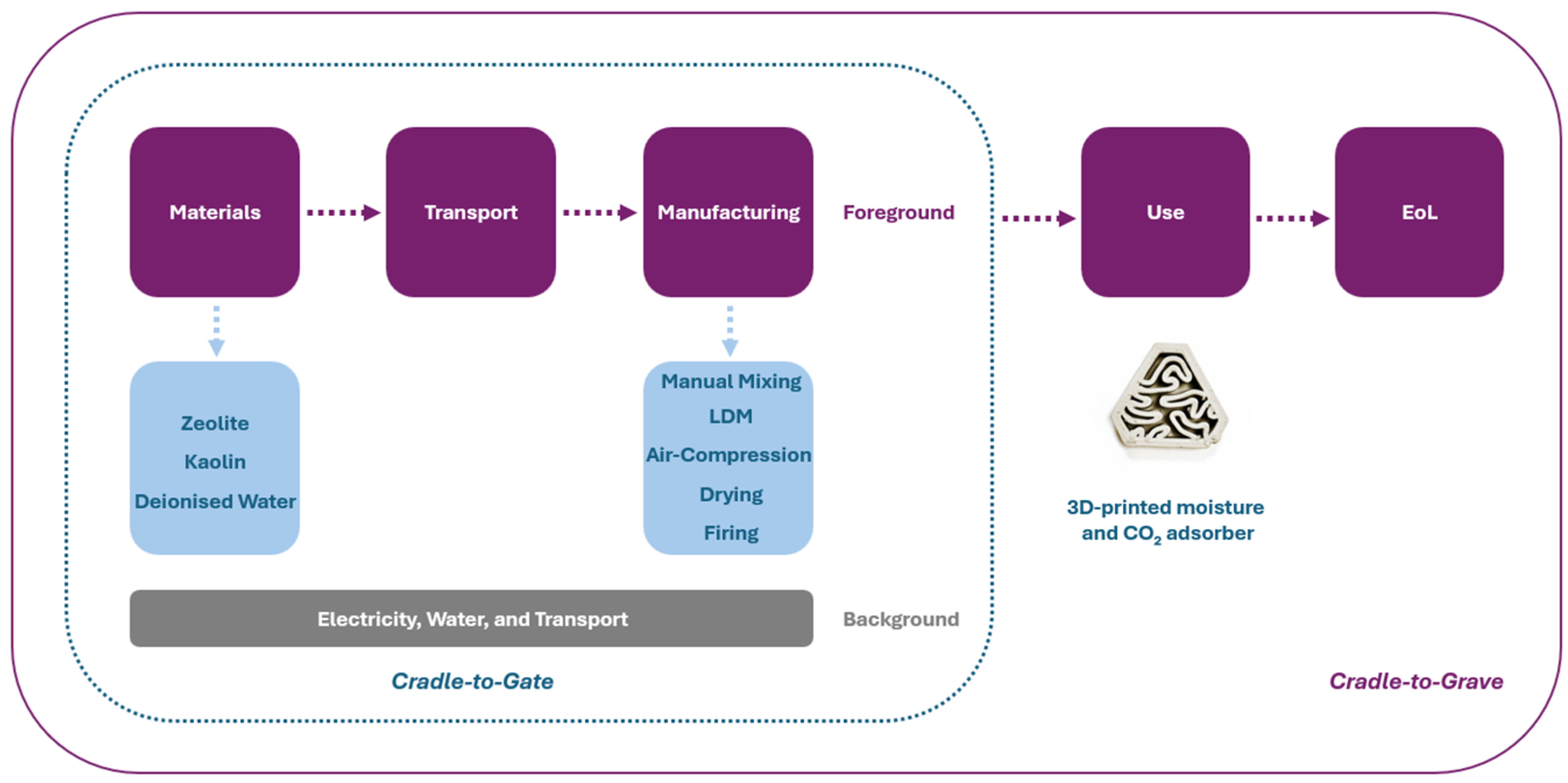

In this study, LCA follows the system boundary approach of “Cradle-to-Gate”, which includes by definition the following stages: extraction of raw materials, transport to the manufacturer, and manufacturing. In particular, the system boundaries considered are illustrated in

Figure 8. It should be mentioned that the raw materials and manufacturing of the equipment and infrastructure used are left out of the system boundaries, since they are out of the study scope, which is exclusively focused on the production of the 3D-printed component.

The Functional Unit (FU) defined in this study is one piece of 3D-printed ceramic component ZKW9:1:5 with 175.56 g of green weight and dimensions of L80.32 mm × W92.75 mm × T30 mm.

2.5.2. Inventory Analysis

The Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) of the ZKW

9:1:5 component under analysis illustrates the material and energy inputs and outputs of the manufacturing process. The LCI was developed by IRES through iterative data gathering in cooperation with BIOG3D, with a reference unit of 14 pieces (pcs) of 3D-printed ZKW

9:1:5 components, reflecting the production capacity of 14 pcs per printing batch (

Table 3). Background data were sourced from the professional database Ecoinvent (Version 3.6) [

45], considering European conditions in terms of water inputs and country specific conditions (Greece, location of BIOG3D) in terms of electricity inputs, taking into account the medium voltage grid. Regarding the transport of materials to the manufacturing location, average European and Global conditions, as well as literature data, were considered.

The LCA modelling of the 3D-printed components is performed using the following estimations and assumptions:

For each infrastructure, the instantaneous electricity consumption was measured (≥5 times) on-site by BIOG3D. These measurements are assumed to reflect the average consumption of each infrastructure, leading to the electricity demands of each device.

No production losses are considered, since the materials and their paste used as input in the 3D-printing are 100% recyclable. In case of any waste occurring by this AM process (i.e., fail prints), the paste can be recycled directly in-house by BIOG3D.

2.5.3. Impact Assessment

The Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) was conducted by the commercial software SimaPro (Version 9.6.0.1) [

46], using the ILCD 2011 Midpoint+ method, released by the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission [

47]. This method includes sixteen midpoint environmental impact categories, including climate change, which is expressed as Global Warming Potential (GWP), with the greenhouse effect over a horizon of 100 years (see

Section 3).

3. Results and Discussion

The multi-criteria framework established during material and process selection directly influenced the environmental performance outcomes quantified via the LCA. By prioritising locally sourced, processed, and functional materials, i.e., Zeolite as the adsorbent compound [

14,

22,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42] and Kaolin as the binder and stabiliser [

44], transportation-related emissions were substantially reduced, resulting in negligible contributions across all midpoint categories.

Furthermore, emphasis on processability and post-drying dimensional stability—validated through the ZKW9:1:5 formulation—was demonstrated via a series of steps: (a) manual syringe-extrusion, (b) printability assessment on single-layer 2D trajectories (i.e., linear, angular, and curved toolpaths), and (c) 3D hexagonal specimens of 30 mm height. These steps proved the effectiveness of the selected LDM material design parameters, minimising defect probability and material collapse during printing. Finally, the decision to employ the LTF Protocol stemmed from the energy efficiency criterion and was confirmed by the LCIA results presented below.

Figure 9 presents the LCIA results for the 3D-printed ZKW

9:1:5 component, showing the contribution of each system input and output per impact category (%) (in 100% stacked columns). The production stage shows a climate change impact of 1.08 kg CO

2 eq per pc, with the total electricity required for manufacturing being the main contributor (53%), followed by the Zeolite (45.5%). Zeolite’s impact arises from fossil CO

2 emissions during powder production.

Regarding electricity use, neither the LDM 3D-printing process (including the air compressor) nor the drying process dominate the climate change impact. Instead, the firing is the most energy-intensive process examined. Under the HTF Protocol (400 °C for 2 h, 800 °C for 2 h), firing alone accounts for 44.8% of the climate change impact.

It is also evident that the electricity demands associated with the firing process and the use of Zeolite, are the predominant contributors across all impact environmental categories examined. Zeolite predominates the “Mineral, fossil, and renewable resource depletion” category, accounting for over 90% of the impact due to the raw ore mining, leading to the depletion of natural resources. By contrast, Kaolin, used at a 1:9 mass ratio relative to Zeolite, as well as the deionised water, have negligible impacts across all categories addressed. Finally, it is observed that the transport of materials to the manufacturer is also negligible, as all materials are locally sourced.

These findings underscore the potential for substantial environmental benefits through process-level interventions, particularly in energy-intensive steps such as firing, which play a predominant role in the overall climate change impact of the production process. In the context of climate change mitigation within manufacturing processes, the reduction in electricity consumption during the firing stage was, therefore, examined using the LTF Protocol (400 °C for 4 h).

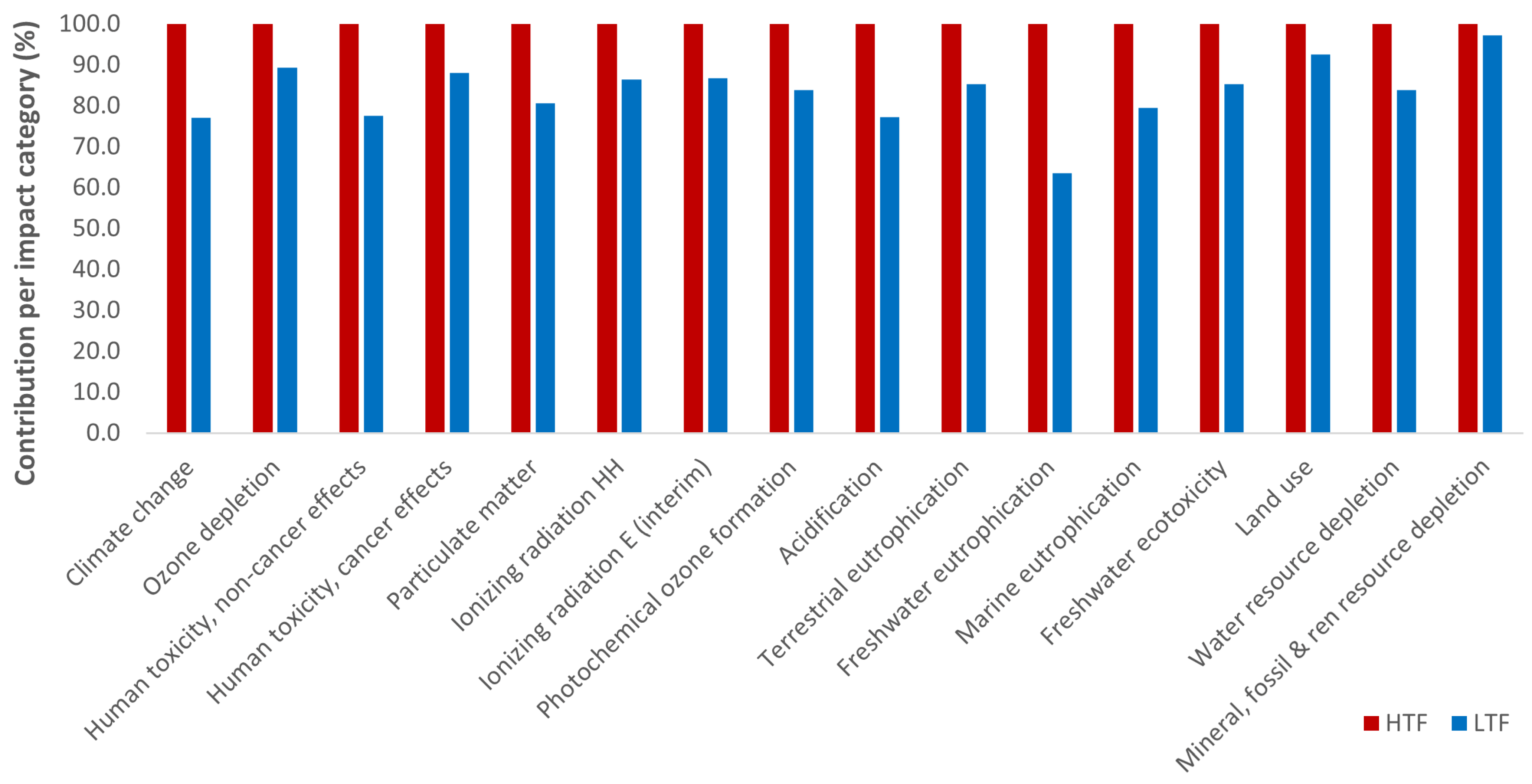

Figure 10 presents the comparative LCIA results for the production stage of the 3D-printed ZKW

9:1:5 component, between the HTF and the LTF Protocols. The results show that the climate change impact is reduced by 23% under the LTF Protocol, with a single 3D-printed humidity and CO

2 adsorber pc contributing 0.83 kg CO

2 eq. As indicated in

Figure 10, transitioning from the HTF to the LTF Protocol leads to a significant reduction in all environmental impact categories, thereby increasing the environmental sustainability of the 3D-printed component.

To conclude, the LCA results indicate that total electricity use is the primary climate change hotspot in the manufacturing process, with firing alone accounting for 44.8% of the impact. By reducing electricity consumption for firing (per batch of 14 components)—from 8.4 kWh (HFT Protocol) to 4.1 kWh (LFT Protocol)—a 23% reduction in CO2 eq emissions is achieved, lowering the impact from 1.08 to 0.83 kg CO2 eq per component. This highlights the critical importance of optimising energy consumption in the firing stage, demonstrating the potential for substantial reductions in the overall carbon footprint of the manufacturing process.

Table 4 presents the absolute values of the comparative LCA results for the HTF and the LTF Protocols by the environmental impact category addressed, including the percentage reduction observed when transitioning from HTF to LTF for the production stage of the 3D-printed component.

4. Conclusions and Future Work

This study demonstrates that a multi-criteria approach to material design and process selection can effectively enhance the environmental performance of 3D-printed ceramic components. By integrating functional, fabrication, and environmental criteria, the developed framework acts as an environmental design lever, linking early-stage decisions on sourcing, composition, detailed design, and processing to quantifiable reductions in resource depletion and emissions intensity. The selected criteria improved shaping control, minimised shrinkage variability, material collapse, and printing defects, with a 3.04% weight loss recorded under the LTF Protocol.

Directly measured energy data, collected using energy metres across the manufacturing chain, provided a practical and cost-efficient approach to overcoming data limitations that often obstruct LCA studies, particularly when novel components are being examined. A key finding is that the electricity demand associated with the LDM-based 3D-printing process does not contribute to the overall environmental impact compared to other system inputs, such as the electricity required for firing. The LCA results confirmed that the LTF Protocol reduces the overall energy resource demands and lowers the climate change impact by 23%, primarily through lower thermal energy inputs and reduced mineral resource use. Since the electricity mix of Greece is primarily fossil-fuel based, reductions in firing energy directly translate into lower emissions intensity, demonstrating the influence of energy-source dependency on environmental performance. The study further underscores the importance of optimising energy-intensive material-related subprocesses, with locally sourced materials helping to minimise transportation-related impacts. In conclusion, integrating LCA with lab-scale manufacturing of innovative 3D-printed components enables early identification of environmental hotspots across the manufacturing chain and facilitates sustainable decision-making for process redesign and optimisation, before scaling up to pilot or commercial level. It should also be noted that as component manufacturing advances towards higher Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs) and upscaled production, the electricity demand per pc of 3D-printed component is expected to decrease due to economies of scale.

The incorporation of LCA insights ensures that the 3D-printed components are designed with a clear understanding of their environmental footprint, paving the way for more informed and sustainable manufacturing practices. Extending the system boundaries to subsequent LCA stages highlights additional opportunities to minimise environmental impacts, especially at the End-of-Life (EoL) stage, by leveraging the recyclability of the components. As a future step, full reusability of the ZKW9:1:5 residual paste (with the addition of water content) shall be investigated to further eliminate material loss and waste-treatment burdens from the system inventory, within a “Cradle-to-Cradle” boundary approach. Alternative component designs that minimise material inputs, exploiting the computational design flexibility in 3D-printing, should also be explored. In the Transport-to-the-Installation-Site stage, local or on-site production and modular packaging can reduce transportation emissions and waste. For the Installation stage of the 3D-printed components in the building site, tool and adhesive-free assembly strategies are expected to lower on-site energy use, labour, and waste, while aligning with scalable, low-impact construction and green certification goals. Finally, future research should evaluate the component regeneration and CO2 valorisation pathways to further enhance sustainability through recycling and resource-efficient practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, V.T. and D.A.; methodology, V.T. and D.A.; software, V.T. and D.A.; validation, V.T. and D.A.; formal analysis, V.T. and D.A.; investigation, V.T. and D.A.; resources, A.K.; data curation, V.T. and D.A.; writing—original draft preparation, V.T. and D.A.; writing—review and editing, V.T., D.A., A.K. and E.P.K.; visualisation, V.T. and D.A.; supervision, A.K. and E.P.K.; project administration, V.T. and A.K.; funding acquisition, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was carried out as part of the H2020 project “iclimabuilt—Functional and advanced insulating and energy harvesting/storage materials across climate adaptive building envelopes” (Grant Agreement no. 952886).

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elena Aeraki (Chemical Engineer—Intern, BioG3D) for the technical support of the project.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Vaia Tsiokou and Anna Karatza are affiliated with BioG3D P.C., and Authors Despoina Antypa and Elias P. Koumoulos are affiliated with Innovation in Research & Engineering Solutions (IRES); they all declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AM | Additive Manufacturing |

| EoL | End-of-Life |

| EU | European Commission |

| FU | Functional Unit |

| GWP | Global Warming Potential |

| HTF | High-Temperature Firing |

| IEQ | Indoor Environmental Quality |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| LCI | Life Cycle Inventory |

| LCIA | Life Cycle Impact Assessment |

| LDM | Liquid Deposition Modelling |

| LTF | Low-Temperature Firing |

| MBV | Moisture Buffer Value |

| TRL | Technology Readiness Level |

References

- Wang, M.; Li, L.; Hou, C.; Guo, X.; Fu, H. Building and Health: Mapping the Knowledge Development of Sick Building Syndrome. Buildings 2022, 12, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas Dodd, S.D.; Mauro, C. Level(s) Indicator 4.1: Indoor Air Quality User Manual: Introductory Briefing, Instructions and Guidance (Publication Version 1.1); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://susproc.jrc.ec.europa.eu/product-bureau/sites/default/files/2021-02/UM3_Indicator_4.1_v1.1_37pp.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Housing and Health Guidelines. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550376 (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- EN 16798–1:2019; Energy Performance of Buildings—Ventilation for Buildings—Part 1: Indoor Environmental Input Parameters for Design and Assessment of Energy Performance of Buildings Addressing Indoor Air Quality, Thermal Environment, Lighting and Acoustics. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Boerstra, A.C. New Health & Comfort Promoting CEN Standard. REHVA J. 2019, 56, 6–7. Available online: https://www.rehva.eu/rehva-journal/chapter/new-health-comfort-promoting-cen-standard (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Olesen, B.W. Indoor Environmental Input Parameters for the Design and Assessment of Energy Performance of Buildings. REHVA J. 2017, 54, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Aerts, D.; Amon, A.; Barta, Z.; Mandin, C.; Moser, S.; Schweiker, M.; Nielsen, M.; Thomson, H.; Wahlberg, A.; Wargocki, P.; et al. Healthy Buildings Barometer 2024 How to Deliver Healthy, Sustainable, and Resilient Buildings for People. 2024. Available online: https://www.bpie.eu/publication/healthy-buildings-barometer-2024-how-to-deliver-healthy-sustainable-and-resilient-buildings-for-people/ (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Van Roijen, E.; Miller, S.A.; Davis, S.J. Building Materials Could Store More than 16 Billion Tonnes of CO2 Annually. Science 2025, 387, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, V.; Libralato, M.; Fantucci, S.; Shtrepi, L.; Autretto, G. Enhancement of the Hygroscopic and Acoustic Properties of Indoor Plasters with a Super Adsorbent Calcium Alginate BioPolymer. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76, 107147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantucci, S.; Fenoglio, E.; Grosso, G.; Serra, V.; Perino, M.; Marino, V.; Dutto, M. Development of an Aerogel-Based Thermal Coating for the Energy Retrofit and the Prevention of Condensation Risk in Existing Buildings. Sci. Technol. Built Environ. 2019, 25, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafizah Ahmad, N.; Zainal Abidin, E.; Karuppiah, K.; Syawani Jasni, A.; Pei Zam, H.; Hassim Ismail, N.; Sapuan Salit, M. Development of Porous Ceramics as Wall Tiles with Humidity Controlling and Antimicrobial Characteristics from Modified Diatomaceous Eart (DE): Potential to Improve Indoor Air Quality. Asia Pac. Environ. Occup. Health J. 2018, 4, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, M.Z. Heat, Air and Moisture Control Strategies for Managing Condensation in Walls. In Proceedings of the BSI 2003 Proceedings, Westford, MA, USA, 7 October 2003; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, M.; Zhang, S.; Dai, S.; Wang, H.; Liu, B. Pressure Drops and Mass Transfer of a 3D Printed Tridimensional Rotational Flow Sieve Tray in a Concurrent Gas–Liquid Column. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 287, 120549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, S.; Li, X.; Thakkar, H.; Rownaghi, A.A.; Rezaei, F. Recent Advances in 3D Printing of Structured Materials for Adsorption and Catalysis Applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 6246–6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A.; Alamoodi, N.; Karanikolos, G.N.; Doumanidis, C.C.; Polychronopoulou, K. A Review on New 3-D Printed Materials’ Geometries for Catalysis and Adsorption: Paradigms from Reforming Reactions and CO2 Capture. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartings, M.R.; Ahmed, Z. Chemistry from 3D-Printed Objects. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2019, 3, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayat, H.; Kashani, A. Reducing Material and Energy Consumption in Single-Story Buildings through 3D-Printed Wall Designs. Energy Build. 2025, 333, 115497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, M.; Mohseni, M.; Aslani, A.; Zahedi, R. Investigation of Thermal Performance and Life-Cycle Assessment of a 3D Printed Building. Energy Build. 2022, 272, 112341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, A.; Navaratnam, S.; Rajeev, P.; Sanjayan, J. Thermal Performance and Life Cycle Analysis of 3D Printed Concrete Wall Building. Energy Build. 2024, 320, 114604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christen, H.; van Zijl, G.; de Villiers, W. Improving Building Thermal Comfort through Passive Design—An Experimental Analysis of Phase Change Material 3D Printed Concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 392, 136247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Bartlett School of Architecture. TerraMound—Exploration with TPMS Geometries. 2023. Available online: https://fifteen2023.bartlettarchucl.com/dfm-2023/terramound (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Thakkar, H.; Eastman, S.; Hajari, A.; Rownaghi, A.A.; Knox, J.C.; Rezaei, F. 3D-Printed Zeolite Monoliths for CO2 Removal from Enclosed Environments. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 27753–27761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, A.; Gianchandani, P.K.; Baino, F. Sustainable Approaches for the Additive Manufacturing of Ceramic Materials. Ceramics 2024, 7, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robayo-Salazar, R.; Martínez, F.; Vargas, A.; Mejía de Gutiérrez, R. 3D Printing of Hybrid Cements Based on High Contents of Powders from Concrete, Ceramic and Brick Waste Chemically Activated with Sodium Sulphate (Na2SO4). Sustainability 2023, 15, 9900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Sharma, V. 3D Printed Bio-Ceramic Loaded PEGDA/Vitreous Carbon Composite: Fabrication, Characterization, and Life Cycle Assessment. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2023, 143, 105904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez, E.; Gallego, J.M.; Colorado, H.A. 3D Printing via the Direct Ink Writing Technique of Ceramic Pastes from Typical Formulations Used in Traditional Ceramics Industry. Appl. Clay Sci. 2019, 182, 105285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posani, M.; Voney, V.; Odaglia, P.; Du, Y.; Komkova, A.; Brumaud, C.; Dillenburger, B.; Habert, G. Low-Carbon Indoor Humidity Regulation via 3D-Printed Superhygroscopic Building Components. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, V.; Vargas Velasquez, J.D.; Fantucci, S.; Autretto, G.; Gabrieli, R.; Gianchandani, P.K.; Armandi, M.; Baino, F. 3D-Printed Clay Components with High Surface Area for Passive Indoor Moisture Buffering. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 91, 109631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/37456.html (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- ISO 14044:2006/Amd 1:2017; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines—Amendment 1. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/72357.html (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Iclimabuilt—Advanced Insulation and Energy Harvesting. Available online: https://iclimabuilt.eu/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Garikipati, K.; Goriely, A.; Kuhl, E.; Menzel, A. Mini-Workshop: Mathematics of Differential Growth, Morphogenesis, and Pattern Selection. Oberwolfach Rep. 2016, 12, 2895–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutten, D. Grasshopper—Algorithmic Modeling for Rhino. Available online: https://www.grasshopper3d.com/ (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Robert McNeel and Associates. Rhinoceros 3D. Available online: https://www.rhino3d.com/ (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Piker, D. Kangaroo Rhino Grasshopper Plugin. Available online: https://docs.packhunt.io/reference/supported_gh_plugins/gh_plugin_kangaroo/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Bo, Z.; Meijia, R.; Wenjian, H.; Linying, S.; Erlin, M.; Jun, L. Study on Temperature-Humidity Controlling Performance of Zeolite-Based Composite and Its Application for Light Quality Energy-Conserving Building Envelope. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 69, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jivrakh, K.B.; Varghese, A.M.; Ehrling, S.; Kuppireddy, S.; Polychronopoulou, K.; Abu Al-Rub, R.K.; Alamoodi, N.; Karanikolos, G.N. 3D-Printed Zeolite 13X Gyroid Monolith Adsorbents for CO2 Capture. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 154674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middelkoop, V.; Coenen, K.; Schalck, J.; Van Sint Annaland, M.; Gallucci, F. 3D Printed versus Spherical Adsorbents for Gas Sweetening. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 357, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, J. Synthesis of Zeolite 4A from Kaolin and Its Adsorption Equilibrium of Carbon Dioxide. Materials 2019, 12, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Bai, P.; Sun, M.; Liu, W.; Li, D.; Wu, W.; Yan, W.; Shang, J.; Yu, J. Fabricating Mechanically Robust Binder-Free Structured Zeolites by 3D Printing Coupled with Zeolite Soldering: A Superior Configuration for CO2 Capture. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1901317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couck, S.; Cousin-Saint-Remi, J.; Van der Perre, S.; Baron, G.V.; Minas, C.; Ruch, P.; Denayer, J.F.M. 3D-Printed SAPO-34 Monoliths for Gas Separation. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2018, 255, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couck, S.; Lefevere, J.; Mullens, S.; Protasova, L.; Meynen, V.; Desmet, G.; Baron, G.V.; Denayer, J.F.M. CO2, CH4 and N2 Separation with a 3DFD-Printed ZSM-5 Monolith. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 308, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, K.; Adethya, V.S.; Ballari, S.O.; Yadav, K.D.; Bansode, S.S.; Shukla, S. Application of Bentonite Clay as a Binding Material. Des. Eng. 2021, 9, 9111–9131. [Google Scholar]

- Dondi, M.; Iglesias, C.; Dominguez, E.; Guarini, G.; Raimondo, M. The Effect of Kaolin Properties on Their Behaviour in Ceramic Processing as Illustrated by a Range of Kaolins from the Santa Cruz and Chubut Provinces, Patagonia (Argentina). Appl. Clay Sci. 2008, 40, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecoinvent, version 3.6; Ecoinvent Association: Zürich, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://www.ecoinvent.org/ (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- SimaPro, version 9.6.0.1; PRé Sustainability: Amersfoort, The Netherlands, 2024. Available online: https://simapro.com/ (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Hauschild, M.; Goedkoop, M.; Guinee, J.; Heijungs, R.; Huijbregts, M.; Jolliet, O.; Margni, M.; De Schryver, A. Recommendations for Life Cycle Impact Assessment in the European Context—Based on Existing Environmental Impact Assessment Models and Factors (International Reference Life Cycle Data System—ILCD Handbook); Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2011; Volume 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |