Towards a Sustainable Intelligent Transformation in E-Commerce: An Empirical Study of User Expectations and Perceptions of Virtual Anchors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Applications of Virtual Anchors Across Different Contexts

2.2. Construction of Virtual Anchor Attribute Indicators

2.3. Expectation–Perception Framework and Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA)

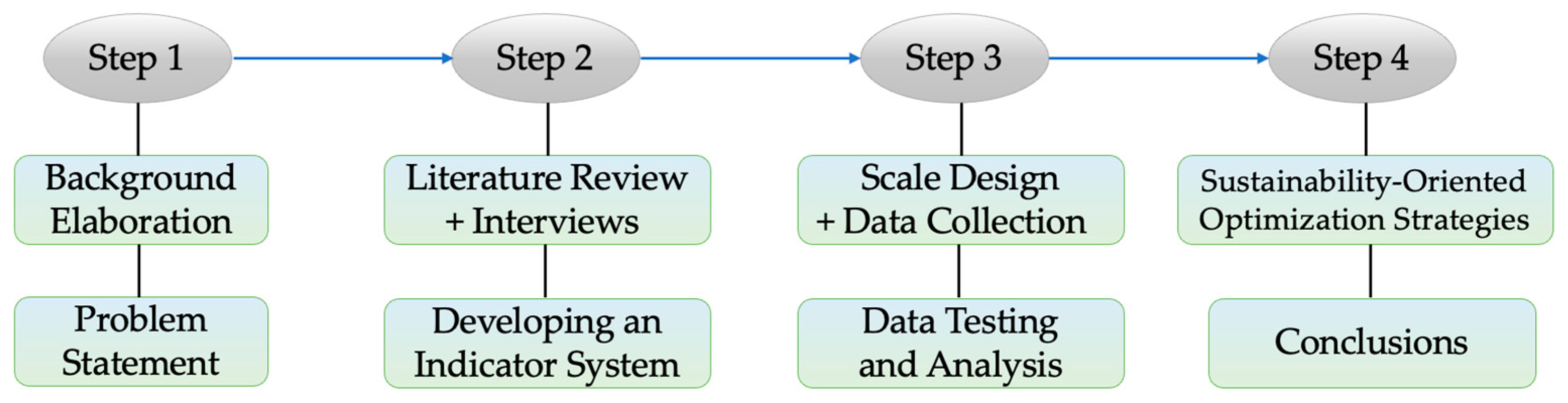

3. Research Design

3.1. Research Framework and Procedure

3.2. Indicator Measurement and Questionnaire Design

3.3. Research Sample and Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis Method

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Demographic Analysis

4.2. Reliability and Validity Tests

4.3. Common Method Bias Test

4.4. Analysis of I–P Values and Paired-Sample T-Test

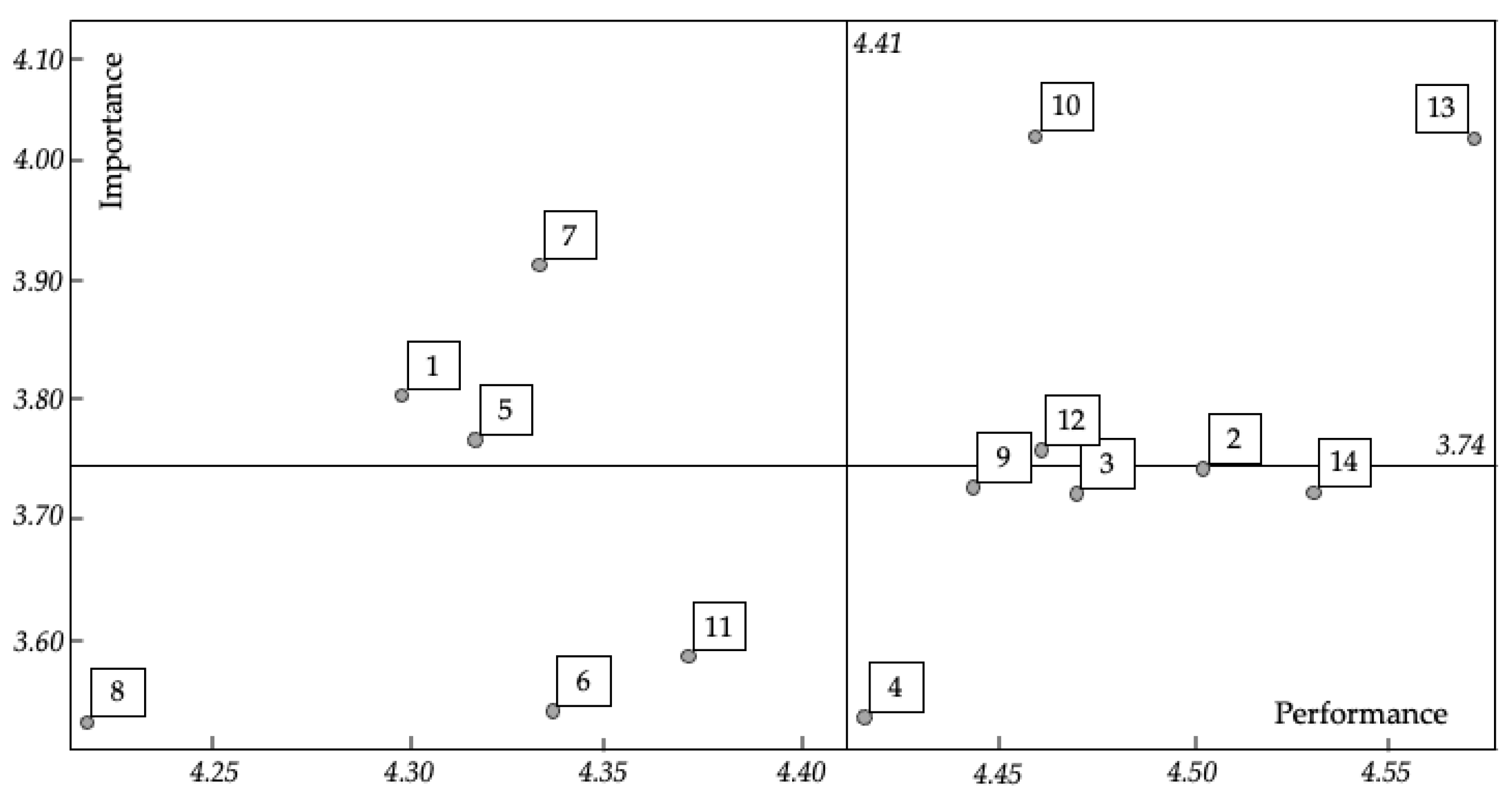

4.5. IPA Matrix Distribution and Discussion

4.5.1. Strength Maintenance Zone (Quadrant I)

4.5.2. Sustainment Zone (Quadrant II)

4.5.3. Low-Priority Improvement Zone (Quadrant III)

4.5.4. Key Improvement Zone (Quadrant IV)

4.5.5. Cross-Platformity: Boundary Attribute and Strategic Potential

5. Implications and Recommendations

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| 1-Gender | |

| 1. Male | 2. Female |

| 2-Age | |

| 1. 19 years or below | 2. 20–29 years |

| 3. 30–39 years | 4. 40 years or above |

| 3-Level of Education | |

| 1. Junior high school degree | 2. High school degree |

| 3. Junior college degree | 4. Bachelor’s degree |

| 5. Master’s degree or above |

Appendix A.2

| Very Unimportant/ Very Dissatisfied | Unimportant/ Dissatisfied | Neutral | Important/ Satisfied | Very Important/ Very Satisfied | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| To What Extent | ||||||

| (1) How important do you consider the following attributes of virtual anchors in e-commerce live streaming? Please rate each attribute on a 5-point Likert scale according to its importance in your expectations. (5 = Very important, 4 = Important, 3 = Neutral, 2 = Unimportant, 1 = Very unimportant) | ||||||

| No. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 1 | Human-like attributes | |||||

| 2 | Cross-platformity | |||||

| 3 | Anthropomorphic appearance | |||||

| 4 | Interactivity | |||||

| 5 | Credibility | |||||

| 6 | Behavioral agency | |||||

| 7 | Emotional bonding | |||||

| 8 | Entertainment | |||||

| 9 | Technical attributes | |||||

| 10 | Novelty | |||||

| 11 | Intelligence | |||||

| 12 | Spectacle | |||||

| 13 | Expressiveness | |||||

| 14 | Professionalism | |||||

| (2) How satisfied are you with the performance of the following characteristics of virtual anchors in e-commerce live streaming? Please rate each item on a 5-point scale according to your actual experience. (5 = Very satisfied, 4 = Satisfied, 3 = Neutral, 2 = Dissatisfied, 1 = Very dissatisfied) | ||||||

| No. | Questionnaire Content | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | Human-like attributes | |||||

| 2 | Cross-platformity | |||||

| 3 | Anthropomorphic appearance | |||||

| 4 | Interactivity | |||||

| 5 | Credibility | |||||

| 6 | Behavioral agency | |||||

| 7 | Emotional bonding | |||||

| 8 | Entertainment | |||||

| 9 | Technical attributes | |||||

| 10 | Novelty | |||||

| 11 | Intelligence | |||||

| 12 | Spectacle | |||||

| 13 | Expressiveness | |||||

| 14 | Professionalism | |||||

References

- Oláh, J.; Popp, J.; Khan, M.A.; Kitukutha, N. Sustainable e-commerce and environmental impact on sustainability. Econ. Sociol. 2023, 16, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aras, G.; Crowther, D. Making sustainable development sustainable. Manag. Decis. 2009, 47, 975–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oláh, J.; Kitukutha, N.; Haddad, H.; Pakurár, M.; Máté, D.; Popp, J. Achieving sustainable e-commerce in environmental, social and economic dimensions by taking possible trade-offs. Sustainability 2018, 11, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Wong, S.F.; Libaque-Saenz, C.F.; Lee, H. E-commerce sustainability: The case of Pinduoduo in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escursell, S.; Llorach-Massana, P.; Roncero, M.B. Sustainability in e-commerce packaging: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryanti, T.; Subriadi, A.P. E-commerce acceptance in the dimension of sustainability. J. Model. Manag. 2022, 17, 715–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M. Environmental sustainability under E-commerce: A holistic perspective. Eur. J. Dev. Stud. 2023, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. The Application Trend and Emotional Interaction of AI Virtual Anchors in the Era of Intelligent Media. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference on Information Economy, Data Modelling and Cloud Computing (ICIDC), Dalian, China, 21–23 June 2024; p. 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Li, Y. A Comparative Study of Virtual Anchor and Traditional Anchor in the Era of Artificial Intelligence. Libr. Prog.-Libr. Sci. Inf. Technol. Comput. 2024, 44, 17535. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Chung, W. Digital Emotional Bonds: How Virtual Anchor Characteristics Drive User Purchase Intention in Livestreaming E-commerce. SAGE Open 2025, 15, 21582440251342981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.Y.; Kweon, S.H. An evaluation of determinants to viewer acceptance of artificial intelligence-based news anchor. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2021, 21, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Dang, Y. Virtuality, simulation and fake: The technical development and philosophical criticism of virtual anchors. Prometeica 2022, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Pan, X. Visual fidelity effects on expressive self-avatar in virtual reality: First impressions matter. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR), Christchurch, New Zealand, 12–16 March 2022; pp. 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibrek, K.; Martin, S.; McDonnell, R. Is photorealism important for perception of expressive virtual humans in virtual reality? ACM Trans. Appl. Percept. 2019, 16, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lang, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X. A research on virtual anchor system based on Kinect sensory technology. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Aviation Safety and Information Technology(ICASIT), Weihai, China, 14–16 October 2020; pp. 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y. More than enough is too much: Curvilinear relationship between anchor body movements and sales in live streaming e-commerce. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 84, 104211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Yang, Y.; Mei, Z.; Xie, Y.; Yu, A. Exploring consumer citizenship behavior by personification of E-commerce virtual anchors based on shopping value. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 76469–76477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ge, S.; Huang, Z. A Study on the Impact of AI Anchor Feature Management on Consumer Purchase Intention—Based on ELM model. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Digital Economy, Blockchain and Artificial Intelligence, Guangzhou, China, 23–25 August 2024; pp. 362–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Cao, L.; Zhou, J. Is the Anthropomorphic Virtual Anchor Its Optimal Form? An Exploration of the Impact of Virtual Anchors’ Appearance on Consumers’ Emotions and Purchase Intention. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Ramasamy, S.S.; Ying, F. Evaluating the Virtual Anchors in Online Shopping Based on User Behaviour and Sales Using SOR Model. Int. J. Instr. Cases 2024, 8, 367–386. Available online: https://ijicases.com/article-view/?id=131 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Battarbee, K.; Koskinen, I. Co-experience: User experience as interaction. CoDesign 2005, 1, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y. Product-independent or product-dependent: The impact of virtual influencers’ primed identity on purchase intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 84, 104088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.P.; Xin, L.; Wang, H.; Park, H.W. Effects of AI virtual anchors on brand image and loyalty: Insights from perceived value theory and SEM-ANN analysis. Systems 2025, 13, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhang, S. The Image Construction of News Anchors Facing Virtual Reality in the Metaverse Environment. Comput. Inform. 2024, 43, 667–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.; Xu, J.; Qin, H.S.; Fu, W.Z.; Shang, Q. Effect of E-commerce Anchor Types on Consumers’ Purchase Behavior: AI Anchors and Human Anchors. J. Manag. Sci. 2023, 36, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y. Has the Booming Digital Human Livestreaming Industry Hit a Bottleneck? Int. Bus. Dly. 2024, 2, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y. The Virtual Evolution, Alienation, and Dissolution of the “Middlemen”—Digital Interpretation Based on Marx’s Theory of Alienated Labor. Adv. Philos. 2024, 13, 2540–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Allbeck, J.M. Virtual humans: Evolving with common sense. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Motion in Games (MIG), Rennes, France, 15–17 November 2012; pp. 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Allbeck, J.M. Imperatives for virtual humans. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalibard, S.; Magnenat-Talmann, N.; Thalmann, D. Anthropomorphism of artificial agents: A comparative survey of expressive design and motion of virtual Characters and Social Robots. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Autonomous Social Robots and Virtual Humans at the 25th Annual Conference on Computer Animation and Social Agents (CASA), Singapore, 9 May 2012; pp. 1–21. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-00732763 (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Sixth Tone. China’s Next-Gen TV Anchors Hustle for a Job AI Is Already Doing. Available online: https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1017300?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Graefe, A.; Bohlken, N. Automated journalism: A meta-analysis of readers’ perceptions of human-written in comparison to automated news. Media Commun. 2020, 8, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, S.; Qiu, S. A Systematic Literature Review on the Negative Impacts of AI-generated Virtual Digital Humans. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 80047–80062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Li, Y.; Jin, H. What do you think of AI? Research on the influence of AI news anchor image on watching intention. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiuchi, K.; Umehara, H.; Irizawa, K.; Kang, X.; Nakataki, M.; Yoshida, M.; Matsumoto, K. An exploratory study of the potential of online counseling for university students by a human-operated avatar counselor. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveys, K.; Sagar, M.; Zhang, X.; Fricchione, G.; Broadbent, E. Effects of emotional expressiveness of a female digital human on loneliness, stress, perceived support, and closeness across genders: Randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, 30624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheperis, C.J.; Annan-Coultas, D.L.; Rush, C.C. Reimagining the Counseling Profession: Preparing Counselors for AI and Digital Health Integration. J. Couns. Prep. Superv. 2025, 19, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, J.; Son, S.; Xu, Z.; Shi, J.; Liu, D.; Liu, F.; Zhou, Y. Visual Persona: Foundation Model for Full-Body Human Customization. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Nashville, TN, USA, 10–17 June 2025; pp. 18630–18641. Available online: https://cvlab-kaist.github.io/Visual-Persona/ (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Dondapati, A.; Dehury, R.K. Virtual vs. human influencers: The battle for consumer hearts and minds. Comput. Hum. Behav. Artif. Hum. 2024, 2, 100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Wang, Z. The ethics of virtuality: Navigating the complexities of human-like virtual influencers in the social media marketing realm. Front. Commun. 2023, 8, 1205610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Shieh, C.H.; van Esch, P.; Ling, I.L. AI customer service: Task complexity, problem-solving ability, and usage intention. Australas. Mark. J. 2020, 28, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolescu, L.; Tudorache, M.T. Human-computer interaction in customer service: The experience with AI chatbots—A systematic literature review. Electronics 2022, 11, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.X. Study on the Application and Challenges of Digital Human Technology in E-Commerce Live Streaming-Taking Taobao’s Digital Human Streamers as an Example. E-Commer. Lett. 2025, 14, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.Z. Research on Content Production in County-level Convergence Media Center with AI Virtual Anchor. Radio TV Broadcast Eng. 2024, 51, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sever, I. Importance-performance analysis: A valid management tool? Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, Q.B.; Hu, Z.Y.; Liu, Y. Analyzing Tourist Satisfaction of Rural Scenic Attractions Based on IPA Model. Data Anal. Knowl. Discov. 2023, 7, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, R.S. Unstructured interviews: Are they really all that bad? Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2022, 25, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Wu, F.Z.; Wang, Z. How Can Artificial Inteligent News Anchor Be Acepted?: Dual Perspectives of Emerging Technology and Social Actor. Glob. J. Media Stud. 2021, 8, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X. A Study on the Parasocial-Relationship Between Vtuber and Fans. Master’s Thesis, Liaoning University, Shenyang, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, C.; Groeppel-Klein, A.; Müller, K. Consumers’ responses to virtual influencers as advertising endorsers: Novel and effective or uncanny and deceiving? J. Advert. 2023, 52, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.S. Research on the Factors Influencing the Trust of AI Broadcasters: Taking CCTV’s “AI Wangguan” as an Example. Master’s Thesis, Hebei University, Baoding, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Peng, A.; Kwong, S.C.; Bannasilp, A. Influence of Virtual Anchor Characteristics on Consumers’ Consumption Willingness. J. Int. Bus. Manag. 2023, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinhui, K.; Tarofderb, A.K. Research on the Impact of AI Virtual anchors Interaction Effects on Consumer Purchase Intentions in E-commerce Live Streaming Scenes. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Publ. 2024, 6, 31–36. Available online: https://ijmrap.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/IJMRAP-V6N8P172Y24.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Zhong, D.; Wu, F.; Huang, Z.; Chen, Y. Navigating the human-digital nexus: Understanding consumer intentions with AI anchors in live commerce. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2025, 44, 4096–4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.X. Situation Analysis of Chinese Virtual Streamer Industry from the View of Media Materiality. Adv. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 1287–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y. The Alienation of Relational Labor among Virtual Anchors under the Power Struggle between Platform Capital and Fans. Youth J. 2024, 30, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Kim, Y.G. Application of the stimuli-organism-response (SOR) framework to online shopping behavior. J. Internet Commer. 2014, 13, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, R.E. Media appropriateness: Using social presence theory to compare traditional and new organizational media. Hum. Commun. Res. 1993, 19, 451–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martilla, J.A.; James, J.C. Importance-performance analysis. J. Mark. 1977, 41, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, P.; Schofield, P. The dynamics of destination attribute importance. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 709–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzler, K.; Sauerwein, E.; Heischmidt, K. Importance-performance analysis revisited: The role of the factor structure of customer satisfaction. Serv. Ind. J. 2003, 23, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abalo, J.; Varela, J.; Manzano, V. Importance values for Importance–Performance Analysis: A formula for spreading out values derived from preference rankings. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.Q.; Hou, S.T.; Li, X.; Zhen, F.L.; Li, Y.Q. Research on the establishment of national TCM Health Tourism Demonstration Zone based on IPA analysis. Chin. Hosp. 2022, 25, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, Q.; Wang, J.; Shi, M.; Liu, W. Unveiling consumer satisfaction with AI-generated museum cultural and creative products design: Using importance–performance analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Q.; Chow, I. Application of importance-performance model in tour guides’ performance: Evidence from mainland Chinese outbound visitors in Hong Kong. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boley, B.B.; McGehee, N.G.; Hammett, A.T. Importance-performance analysis (IPA) of sustainable tourism initiatives: The resident perspective. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.K.; Chen, I.S. An Inno-Qual performance system for higher education. Scientometrics 2012, 93, 1119–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, O.I.; Hatos, R.; Bugnar, N.G.; Sasu, D.; Popa, A.L.; Fora, A.F. Evaluation of the quality of higher education services by revised IPA in the perspective of digitization. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.W.; Liu, Y.; Fan, Z.P.; Zhang, J. Wisdom of crowds: Conducting importance-performance analysis (IPA) through online reviews. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 460–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.L.; Hu, Y.R.; Liu, H.J. LSTM and LDA Fusion Algorithm Analysis of Online Brand Community for Users’ focus Hot Spots. J. Intell. 2021, 39, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenburg, N.M.; Magal, S.R. Applying importance-performance analysis to evaluate e-business strategies among small firms. E-Service 2004, 3, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.L.; Dong, L.P. A Study on the Improvement Path of Online Fresh Food Platform Satisfaction: Based on the IPA Analysis Method. Mark. Mod. 2023, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Long, L. Statistical tests and control methods for common method bias. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 12, 942–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Wen, Z. Testing for common method bias: Problems and recommendations. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 43, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, E.; Yang, J. How perceived interactivity affects consumers’ shopping intentions in live stream commerce: Roles of immersion, user gratification and product involvement. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 754–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Han, Q.; Lian, Z.; Zhu, W.; Jiang, Y. From Certainty to Doubt: The Impact of Streamer Expression Certainty on Consumer Purchase Behavior in Live-Stream E-Commerce. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, E.; Silberman, M.S. Rating working conditions on digital labor platforms. Comput. Support. Coop. Work (CSCW) 2019, 28, 911–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.P. A Study on Language Expression and Communication Effect in Journalism and Communication. J. News Res. 2024, 15, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Cheng, S.; Zhou, W.; Yu, S.; Lin, X. A study on the impact of linguistic persuasive styles on the sales volume of live streaming products in social e-commerce environment. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.C.; Zhang, L. “Should a Potter Praise His Pot?”: The Influence of Streamers’ Excessive Praise on Consumers’ Purchase Intention in Live Streaming. Manag. Rev. 2024, 36, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.L.; Zhong, H.Y.; Yu, F. The Underlying Logic, Effectiveness Evaluation, and Development Path of Virtual You Tuber to Promote Consumers’ Purchase Behavior. J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. 2024, 43, 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Elston, D.M. The novelty effect. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 2021, 85, 565–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankton, N.; McKnight, D.H.; Thatcher, J.B. Incorporating trust-in-technology into expectation disconfirmation theory. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2014, 23, 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankton, N.K.; McKnight, D.H.; Wright, R.T.; Thatcher, J.B. Research note—Using expectation disconfirmation theory and polynomial modeling to understand trust in technology. Inf. Syst. Res. 2016, 27, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jin, H.X. A Study on Intellectual Property Infringement of AI Anchors’ Likeness in E-Commerce. E-Commer. Lett. 2025, 14, 2050–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F. Governance Challenges and Response Strategies of Virtual Digital Person Live Streaming with Goods. E-Commer. Lett. 2025, 14, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.S.; Choe, M.J.; Zhang, J.; Noh, G.Y. The role of wishful identification, emotional engagement, and parasocial relationships in repeated viewing of live-streaming games: A social cognitive theory perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 108, 106327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, S.; Zheng, C.; Cho, D.; Kim, Y.; Dong, Q. The impact of interpersonal interaction on purchase intention in livestreaming e-commerce: A moderated mediation model. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D.L.; Novak, T.P. Consumer and object experience in the internet of things: An assemblage theory approach. J. Consum. Res. 2018, 44, 1178–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.H.; Rust, R.T. Artificial intelligence in service. J. Serv. Res. 2018, 21, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J. The Application Challenges and Breakthrough Paths of AI Virtual Hosts for E-Commerce Promotion. E-Commer. Lett. 2025, 14, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, M. Bukimi no tani [The uncanny valley]. Energy 1970, 7, 33–35. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Bukimi+No+Tani+%28The+Uncanny+Valley%29&author=Masahiro+Mori&publication_year=1970&journal=Energy&pages=33-5 (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Shridhar, K. How Close Are Chatbots to Passing the Turing Test? Chatbots Mag. Chatbots Magazine. 2017. Available online: https://chatbotsmagazine.com/how-close-are-chatbots-to-pass-turing-test-33f27b18305e (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Zhan, Y.Q. Analysis of the Value Dilemma Brought by Network Broadcast to Contemporary College Students. Adv. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 6168–6174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, K.L.; Biocca, F. The effect of the agency and anthropomorphism on users’ sense of telepresence, copresence, and social presence in virtual environments. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 2003, 12, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epley, N.; Waytz, A.; Cacioppo, J.T. On seeing human: A three-factor theory of anthropomorphism. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 114, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J. Live-streamer as Digital Labor: A Systemic Review. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2023, 13, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Zhang, Q. The Impact of Interactivity on Virtual Gifts Giving Intent-Based on Live-Streaming Platforms. In Proceedings of the 2018 3rd International Conference on Humanities Science, Management and Education Technology (HSMET), Nanjing, China, 8–10 June 2018; pp. 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Gui, X.; Kou, Y. Multi-platform content creation: The configuration of creator ecology through platform prioritization, content synchronization, and audience management. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Hamburg, Germany, 23–28 April 2023; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadeni, K.; Santoso, E.; Jing, W. Creative Content Monetization: Case Studies on Digital Platforms. J. Soc. Entrep. Creat. Technol. 2025, 2, 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Abidin, C. Visibility labour: Engaging with Influencers’ fashion brands and OOTD advertorial campaigns on Instagram. Media Int. Aust. 2016, 161, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poell, T.; Nieborg, D.; Van Dijck, J. Platformisation. Internet Policy Rev. 2019, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scholars | Research Content | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Wang, Y. X [48] | The study verified that the novelty, credibility, human-likeness, and agency of virtual anchors positively influence audience acceptance of AI anchors through the mediating role of attitude. | literature |

| Tian, X [49] | The human-like appearance and behavior of virtual anchors, along with real-time interactivity and diverse modes of interaction, have the potential to influence consumers’ emotions. Their effect on engagement behavior is particularly pronounced when they can effectively convey information and demonstrate professional competence. | literature |

| Franke, C [50] | An increasing number of brands are employing virtual characters as their endorsers. Does this trend arise because virtual characters are more appealing than human ones, or because they can provide greater advertising novelty? | literature |

| Liu, M. S [51] | The study categorized the characteristics of news AI anchors into four dimensions: human-likeness, professionalism, likability, and intelligence, in order to examine their effects on users’ trust in the anchors. | literature |

| Yu, Y [52] | The study demonstrated that virtual anchors’ appearance attractiveness, interactivity, and entertainment features positively influence audiences’ purchase intentions. | literature |

| Jinhui, K [53] | The study identified five primary factors influencing the interaction effectiveness of AI virtual anchors: personalized interaction experience, entertainment value, real-time responsiveness, efficient content delivery, and realism of the anchor’s image. These factors affect customers’ sense of social presence, which in turn impacts their purchase intentions. | literature |

| Zhong, D [54] | The study examined the relationship between consumers’ perceived human-likeness and perceived intelligence of virtual anchors and their trust, and further validated that trust subsequently influences consumers’ purchase intentions. | literature |

| Dr. Wang | From a special effects perspective, virtual anchors really show off the huge potential of technology. In traditional effects production, we’re often limited by time, budget, and tech, so some supernatural effects are just impossible. But with virtual anchors, advanced digital tech and effects make it easy to pull off amazing supernatural abilities like flying, transforming, or teleporting. Using this tech not only gives virtual anchors way more room to perform, but also delivers an incredible visual punch and immersive experience for the audience. | Interview |

| Zhang (anchor) | You know, as a host, I often feel the challenges that come with different platforms. Audiences on each platform have their own tastes and preferences. Sometimes, platform contracts even stop us from freely doing activities on other platforms, which makes things even harder. But virtual anchors could be a whole new advantage, even an opportunity, and they might help us achieve much greater success in e-commerce live streaming. | Interview |

| Dimension | Attribute | Attribute Description |

|---|---|---|

| Human-like attributes | Cross-platformity | The ability of virtual anchors to maintain a consistent identity and performance across multiple platforms. |

| Anthropomorphic appearance | The degree to which virtual anchors simulate human characteristics in visual and behavioral design. | |

| Interactivity | The ability of virtual anchors to engage in real-time dialogue, feedback, and contextual responses with users. | |

| Credibility | The extent to which users perceive the information or recommendations provided by virtual anchors as trustworthy and reliable. | |

| Behavioral agency | The degree to which virtual anchors demonstrate autonomy and situational adaptability in their actions. | |

| Emotional bonding | The emotional attachment and sense of companionship formed by users through prolonged interaction with virtual anchors. | |

| Entertainment | The ability of virtual anchors to provide pleasure, amusement, and immersive experiences during live streaming. | |

| Technical attributes | Novelty | The innovativeness and originality of virtual anchors in design, performance, or content, reflecting their technological appeal. |

| Intelligence | The ability of virtual anchors to understand, reason, and respond appropriately based on AI technologies. | |

| Spectacle | The display of visually striking and technologically enhanced effects that transcend reality, providing users with a sense of “supernatural power.” | |

| Expressiveness | The richness and accuracy of verbal and non-verbal expressions demonstrated by virtual anchors. | |

| Professionalism | The depth of professional knowledge and the accuracy of information exhibited by virtual anchors. |

| Features | Classification | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 132 | 42.7% |

| Female | 177 | 57.3% | |

| Age | 19 years or below | 53 | 17.2% |

| 20–29 years | 101 | 32.7% | |

| 30–39 years | 87 | 28.2% | |

| 40 years or above | 68 | 21.9% | |

| Education | Junior high school degree | 17 | 5.5% |

| High school degree | 41 | 13.3% | |

| Junior college degree | 69 | 22.3% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 109 | 35.3% | |

| Master’s degree or above | 73 | 23.6% |

| Items | Total (n = 309) | Cronbach’s A | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I value (Importance) | 14 | 309 | 0.928 |

| p value (Performance) | 14 | 309 | 0.825 |

| Construct | KMO Measure | Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity |

|---|---|---|

| Importance (I) | 0.951 | χ2 = 2265.513, df = 91, p < 0.001 |

| Performance (P) | 0.876 | χ2 = 904.584, df = 91, p < 0.001 |

| Paired ID | Items | Mean | Standard Deviation | ΔM | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Human-likeness (I) | 4.29 | 1.05 | 0.50 | 7.190 | 0.000 ** |

| Human-likeness (P) | 3.80 | 1.12 | ||||

| 2 | Cross-platformity (I) | 4.50 | 1.01 | 0.76 | 10.427 | 0.000 ** |

| Cross-platformity (P) | 3.74 | 1.25 | ||||

| 3 | Anthropomorphic appearance (I) | 4.47 | 0.88 | 0.76 | 10.398 | 0.000 ** |

| Anthropomorphic appearance (P) | 3.72 | 1.25 | ||||

| 4 | Interactivity (I) | 4.41 | 0.93 | 0.88 | 11.204 | 0.000 ** |

| Interactivity (P) | 3.53 | 1.27 | ||||

| 5 | Credibility (I) | 4.31 | 1.07 | 0.55 | 7.542 | 0.000 ** |

| Credibility (P) | 3.76 | 1.19 | ||||

| 6 | Behavioral agency (I) | 4.34 | 1.04 | 0.80 | 10.297 | 0.000 ** |

| Behavioral agency (P) | 3.54 | 1.21 | ||||

| 7 | Emotional bonding (I) | 4.32 | 1.08 | 0.41 | 6.228 | 0.000 ** |

| Emotional bonding (P) | 3.91 | 0.98 | ||||

| 8 | Entertainment (I) | 4.21 | 0.93 | 0.69 | 9.155 | 0.000 ** |

| Entertainment (P) | 3.53 | 1.19 | ||||

| 9 | Technical attributes (I) | 4.45 | 0.96 | 0.73 | 10.014 | 0.000 ** |

| Technical attributes (P) | 3.72 | 1.17 | ||||

| 10 | Novelty (I) | 4.46 | 1.00 | 0.45 | 5.831 | 0.000 ** |

| Novelty (P) | 4.01 | 1.03 | ||||

| 11 | Intelligence (I) | 4.37 | 0.98 | 0.77 | 9.958 | 0.000 ** |

| Intelligence (P) | 3.59 | 1.13 | ||||

| 12 | Spectacle (I) | 4.45 | 0.98 | 0.71 | 9.005 | 0.000 ** |

| Spectacle (P) | 3.75 | 1.23 | ||||

| 13 | Expressiveness (I) | 4.60 | 0.74 | 1.07 | 13.885 | 0.000 ** |

| Expressiveness (P) | 3.52 | 1.28 | ||||

| 14 | Professionalism (I) | 4.53 | 0.69 | 0.82 | 12.017 | 0.000 ** |

| Professionalism (P) | 3.72 | 1.16 |

| ID | Dimension | Importance | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Human-like attributes | 4.29 | 3.80 |

| 2 | Cross-platformity | 4.50 | 3.74 |

| 3 | Anthropomorphic appearance | 4.47 | 3.72 |

| 4 | Interactivity | 4.41 | 3.53 |

| 5 | Credibility | 4.31 | 3.76 |

| 6 | Behavioral agency | 4.34 | 3.54 |

| 7 | Emotional bonding | 4.32 | 3.91 |

| 8 | Entertainment | 4.21 | 3.53 |

| 9 | Technical attributes | 4.45 | 3.72 |

| 10 | Novelty | 4.60 | 4.01 |

| 11 | Intelligence | 4.37 | 3.59 |

| 12 | Spectacle | 4.45 | 3.75 |

| 13 | Expressiveness | 4.60 | 4.01 |

| 14 | Professionalism | 4.53 | 3.72 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zou, C.; Dang, Q. Towards a Sustainable Intelligent Transformation in E-Commerce: An Empirical Study of User Expectations and Perceptions of Virtual Anchors. Sustainability 2026, 18, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010016

Zou C, Dang Q. Towards a Sustainable Intelligent Transformation in E-Commerce: An Empirical Study of User Expectations and Perceptions of Virtual Anchors. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleZou, Changyun, and Qiong Dang. 2026. "Towards a Sustainable Intelligent Transformation in E-Commerce: An Empirical Study of User Expectations and Perceptions of Virtual Anchors" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010016

APA StyleZou, C., & Dang, Q. (2026). Towards a Sustainable Intelligent Transformation in E-Commerce: An Empirical Study of User Expectations and Perceptions of Virtual Anchors. Sustainability, 18(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010016