Hierarchical Analysis for Construction Risk Factors of Highway Engineering Based on DEMATEL-MMDE-ISM Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

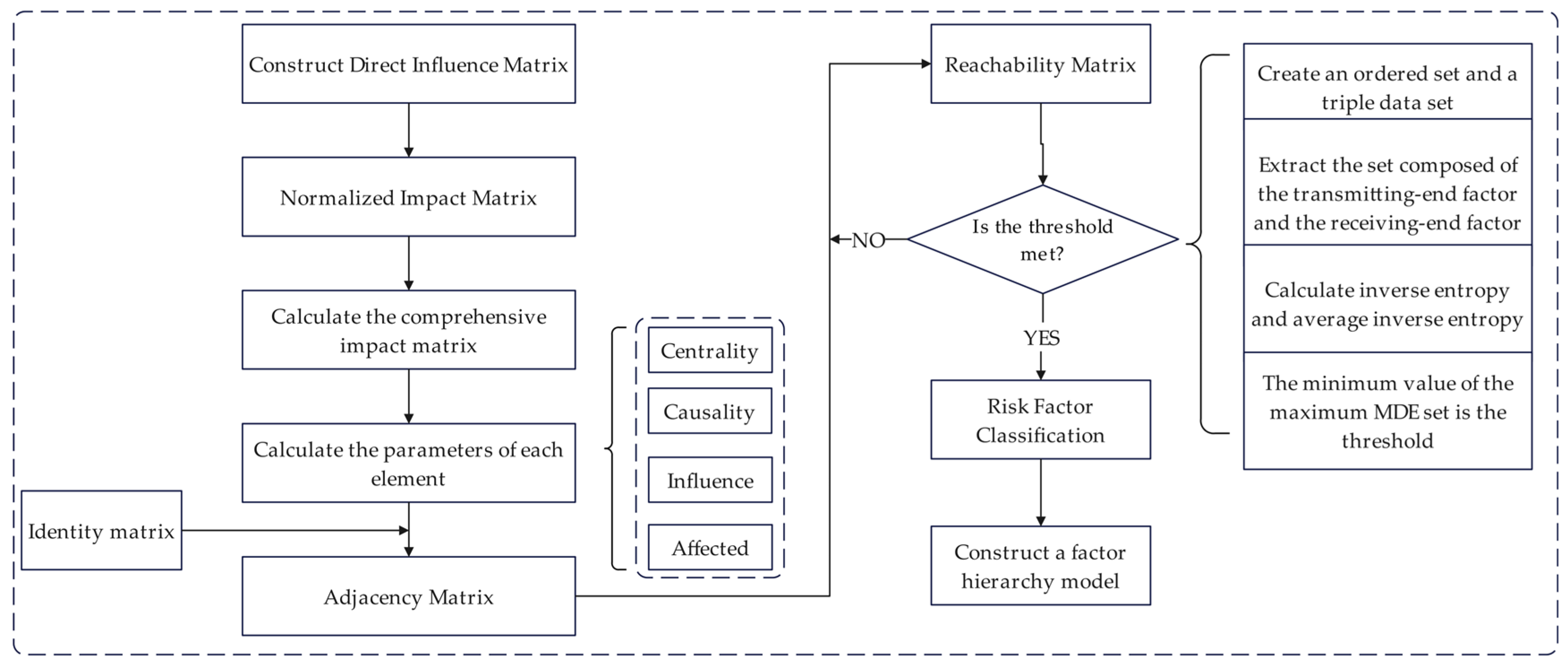

2. Methodology

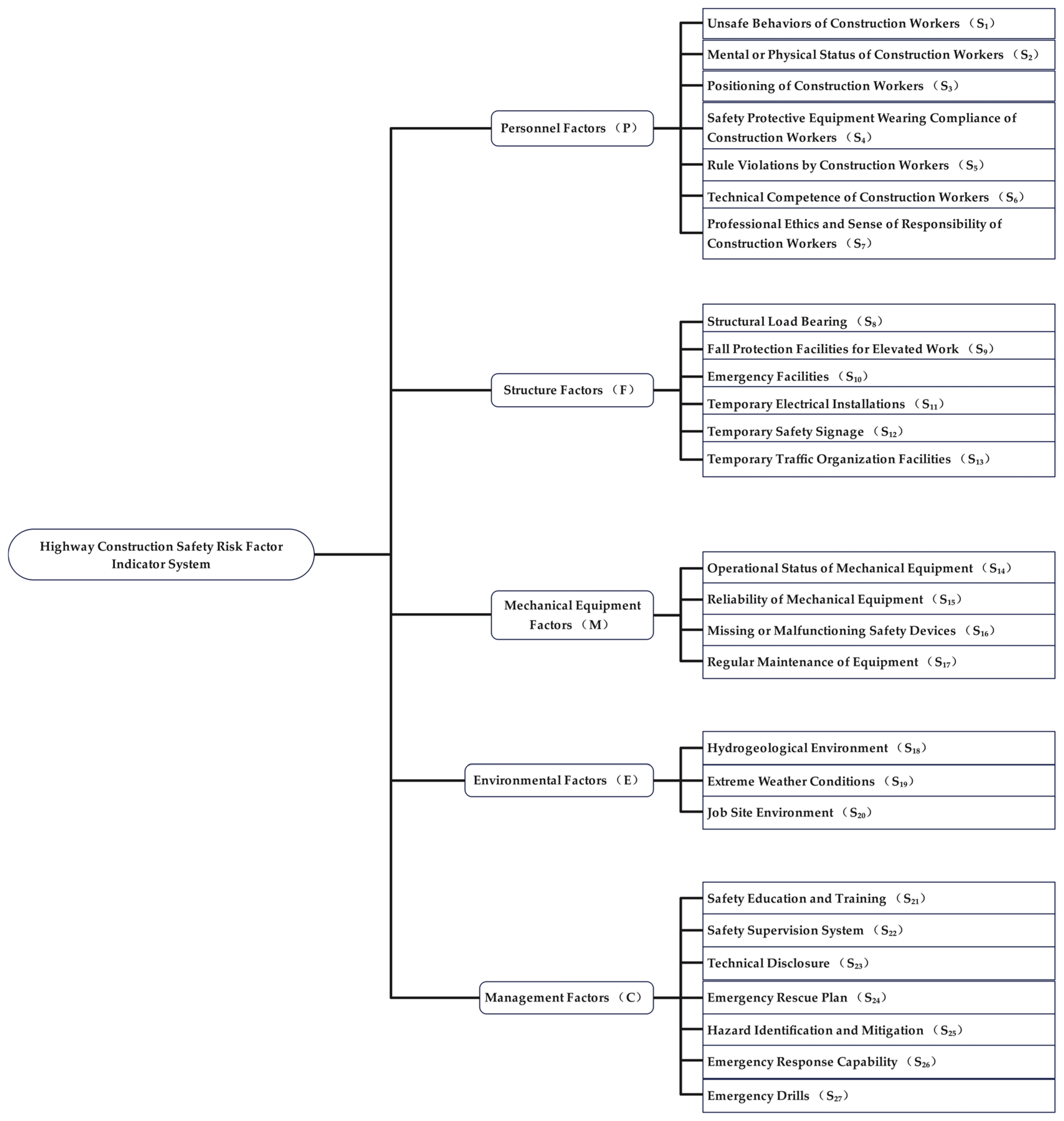

3. Indicator System for Construction Risk Factors of Highway Engineering

3.1. Data Sources and Expert Panel

3.2. Scoring Process and Data Validation

4. Research Results and Discussion

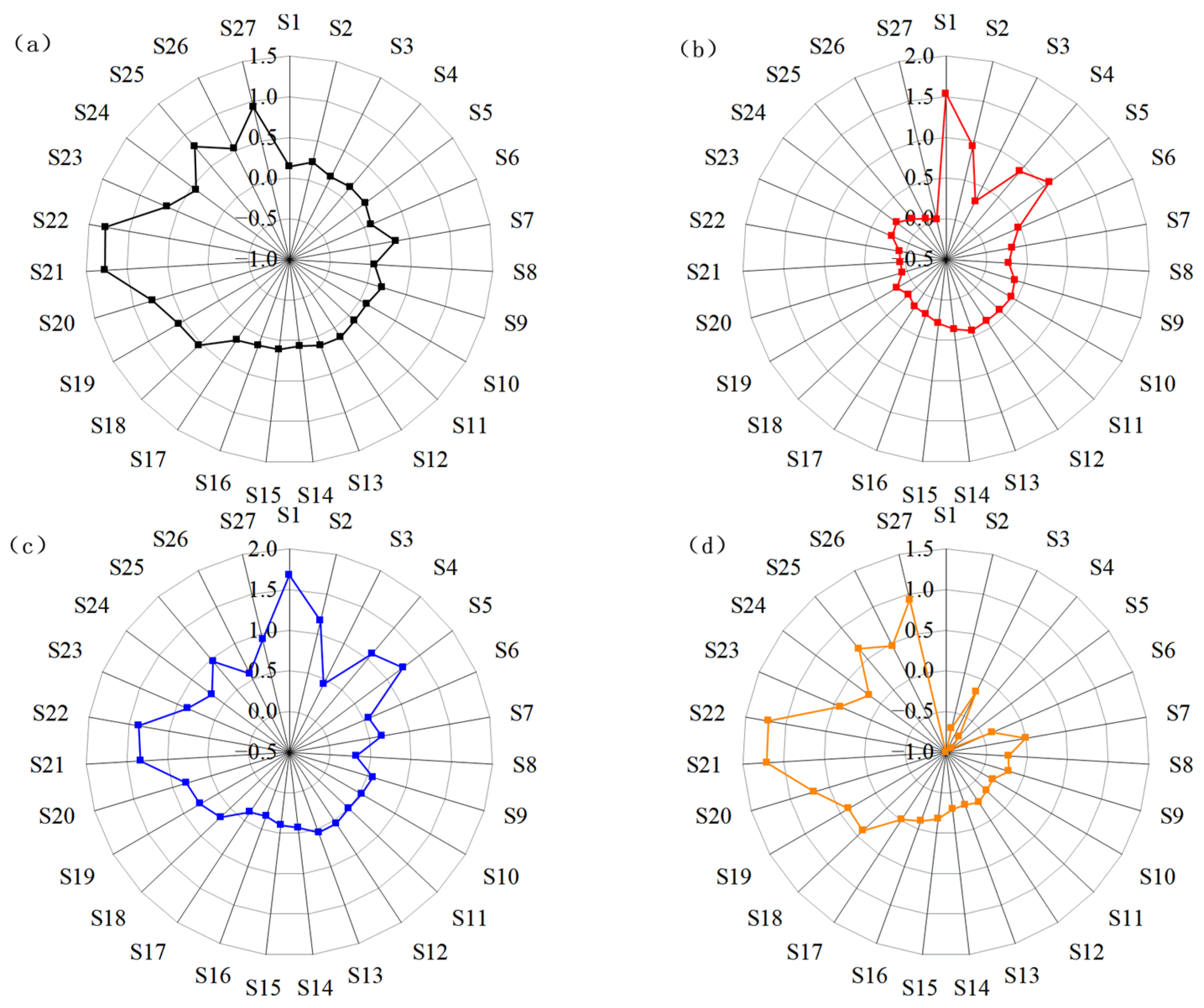

4.1. Matrix Construction and Core Degree Analysis

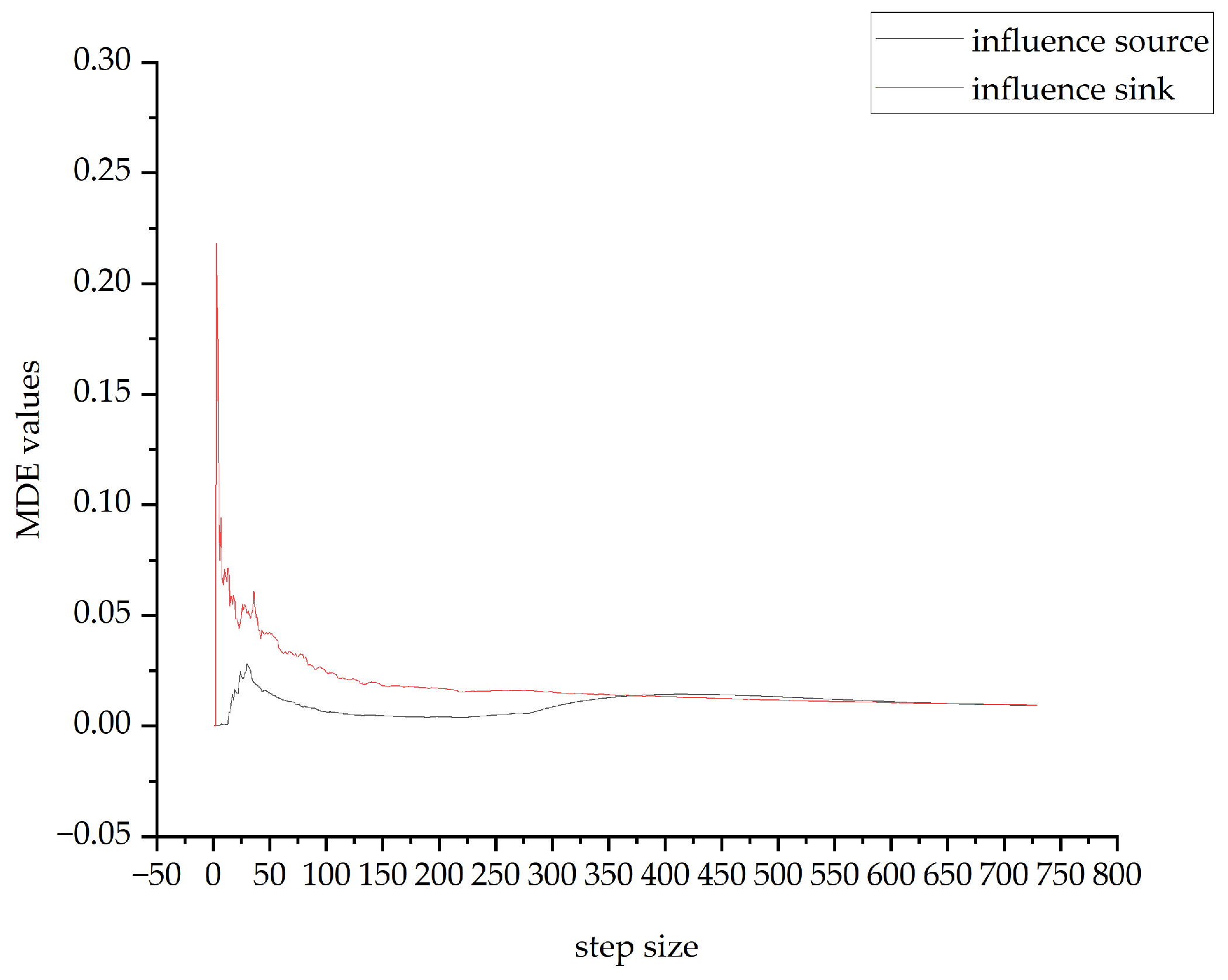

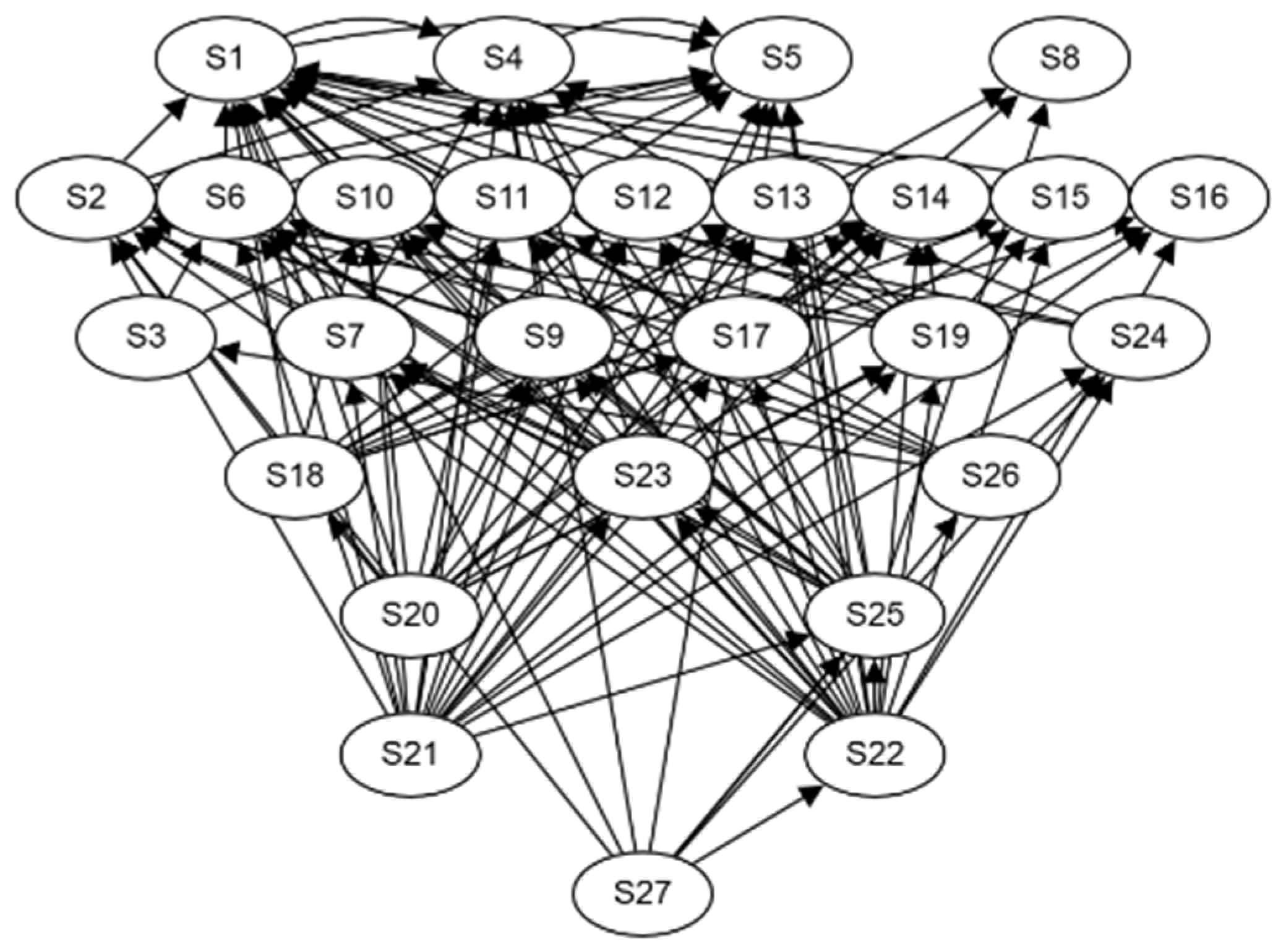

4.2. Threshold Determination and Hierarchical Model Analysis

5. Comparison Results and Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Su, Y.K. Prominence Factors of Recycled Concrete Based on the DEMATEL-ISM Method. J. Shenyang Jianzhu Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2024, 26, 479–486. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, L.H.; Zhang, R.H.; Ming, H.J.; Li, Y.H.; Li, C.X.; Zou, S.X. Accident Causation Chain Analysis of Hydropower Unit Maintenance Operations Based on the DEMATEL-ISM Method. J. Water Resour Hydropower Technol. 2024, 44, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Alqahtani, Y.A.; Makki, A.A. A DEMATEL-ISM Integrated Modeling Approach of Influencing Factors Shaping Destination Image in the Tourism Industry. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankur, C.; Amol, S.; Sanjay, J. An Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) and Decision-Making Trail and Evaluation Laboratory (DEMATEL) Method Approach for the Analysis of Barriers of Waste Recycling in India. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2018, 68, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.Z.; Wu, J.L. Analysis of Influencing Factors on Vocational Education Teacher Team Building Based on DEMATEL-ISM. J. Ningbo Vocat. Tech. Coll. 2025, 29, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.Y.; Dong, X.W.; Li, R.X.; Yu, S.J.; Xue, J.Y. Accident Cause Analysis of Agricultural Machinery Based on DEMATEL-ISM. South Agric. Mach. 2025, 56, 15–19+27. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.T.; Long, C.; Wang, Z.W. Research on Collaborative Influencing Factors and Capability Enhancement of Emergency Logistics Service Supply Chain Based on DEMATEL-ISM. J. Supply Chain. Manag. 2025, 6, 40–53. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, H.; Chen, J.Y.; Li, G.Z.; Zhang, S.T.; Qiang, C.J.; Zhang, H. Research on Resilience Influencing Factors in Civil Aviation Fuel Supply Chain Based on DEMATEL-ISM Model. J. Civ. Aviat. 2025, 9, 138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Deng, S.J.; Yu, G.B. Analysis of Safety Influencing Factors for Storage, Transportation, Dispatching, and Shipping Based on Improved DEMATEL-ISM. Fire Control Command. Control 2025, 50, 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Dai, P.; Zhao, F.L.; Cui, K.X. Tourism Safety Risk Assessment of Mountain-Type Scenic Areas: A Case Study of Beijing. J. Saf. Sci. China 2024, 34, 168–177. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.Z. Risk Early Warning and Legal Safeguard System Construction for Sports Injury Accidents in Universities—Review of “Research on Risk Management and Legal Response Mechanisms for Campus Sports Personal Injury Accidents”. J. Saf. Sci. China 2024, 34, 226. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.E.; Jing, H.F.; Guo, Z.X.; Wang, C.J. A Risk Early-Warning Model for Technology Transfer in Major Engineering Projects Based on DEMATEL-ISM-BN. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 1315–1327. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Y.S.; Zhu, Y.Q.; Wang, N.M.; Zhang, Q.L. Risk Analysis of Railway Bridge and Tunnel Engineering Technical Interfaces Based on DEMATEL, ISM, and BN. J. Chongqing Jiaotong Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2023, 42, 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, M.; Huang, H. Evaluation of Sustainable Agricultural Mechanization Development in Hubei Province Using Fuzzy DEMATEL-ISM. J. Agric. Eng. 2022, 38, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.J.; Chen, H.H.; Cheng, B.Q.; Hu, X.D.; Cai, Q. A Study on the Formation Model of Safety Atmosphere in Metro Construction Based on Fuzzy ISM-DEMATEL. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2021, 18, 2200–2208. [Google Scholar]

- Sahebi, I.G.; Toufighi, S.P.; Azzavi, M.; Masoomi, B.; Maleki, M.H. Fuzzy ISM-DEMATEL Modeling for the Sustainable Development Hindrances in the Renewable Energy Supply Chain. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2024, 18, 43–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, K.; Xia, J.B.; Zhang, X.Y.; Shen, J. System Structural Analysis of Communication Networks Based on DEMATEL-ISM and Entropy. J. Cent. South Univ. 2017, 24, 1594–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.X.; Sun, S.G.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Wang, Z.Q.; Chen, B.Q.; Ma, C. System Failure Analysis Based on DEMATEL–ISM and FMECA. J. Cent. South Univ. 2014, 21, 4518–4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.H.; Dang, R.; Liu, K.C. Health Status Assessment of Ancient Architectural Timber Structures Combined with DEMATEL-ISM-ANP. J. Northwest Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2025, 55, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Song, Y.C.; Wu, L.Y.; Zhao, X.T. Road Congestion Risk Assessment Method for Downstream Vehicles Based on Improved DEMATEL-ISM Model. J. Guangxi Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2024, 49, 146–154. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.P.; Zhang, B.Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.Y.; Li, F.; Zhao, Y.D. Blockchain-Based Optimization of Grain and Oil Quality and Safety Using DEMATEL-ISM. J. Agric. Mach. 2022, 53, 412–423. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Wang, J.; Song, Y.; Yuan, C.; He, J.; Chen, Z. Influencing Factors Analysis of Supply Chain Resilience of Prefabricated Buildings Based on PF-DEMATEL-ISM. Buildings 2022, 12, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.H.; Xia, J.B.; Chen, C.Q. A Network Genealogical Model with Reachable Influence Factors Based on Decision Experiment, Evaluation Experiment Method, and Interpretive Structural Model. J. Jilin Univ. (Eng.) 2012, 42, 782–788. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.D.; Yang, A.B.; Wang, Z.H.; Zhao, J.R.; Dong, G.Y.; Tong, R.P. Human Reliability Analysis of Emergency Responders in Hazardous Chemical Accidents in Chemical Industrial Parks. J. Saf. Sci. China 2025, 35, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. Technical Requirements for Safety Monitoring and Early Warning Systems in Highway Engineering Construction: JT/T 1498-2024; People’s Communications Press: Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Ma, F.; Wu, Y.; Han, B.; Luo, L. MFMDepth: Metaformer-Based Monocular Metric Depth Estimation for Distance Measurement in Ports. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2025, 207, 111325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Pu, Z.; Liu, P.; Qian, T.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y. Efficient Predictive Control Strategy for Mitigating the Overlap of EV Charging Demand and Residential Load Based on Distributed Renewable Energy. Renew. Energy 2025, 240, 122154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ma, Q.; Wu, H.; Shang, W.; Han, B.; Biancardo, S.A. Autonomous Port Traffic Safety-Oriented Vehicle Kinematic Information Exploitation via Port-Like Videos. Transp. Saf. Environ. 2025, 7, tdaf048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Field | Number of Experts | Distribution of Work Experience |

|---|---|---|

| University Research | 16 | 4 with 10–15 years; 12 with >15 years |

| Industry Enterprises | 8 | 2 with 10–15 years; 6 with >15 years |

| Government Supervision | 11 | 1 with 10–15 years; 10 with >15 years |

| Dimensions | Preliminary Indicators | Recognition Ratio | Final Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Construction Workers | Unsafe behaviors of construction workers | 100% | Unsafe behaviors of construction workers |

| Psychological or physical conditions of construction workers | 51.72% | Psychological or physical conditions of construction workers | |

| Positioning of construction workers | 62.07% | Positioning of construction workers | |

| Use of personal protective equipment by construction workers | 89.66% | Use of personal protective equipment by construction workers | |

| Violations of operating procedures by construction workers | 96.55% | Violations of operating procedures by construction workers | |

| Technical competence of construction workers | 62.07% | Technical competence of construction workers | |

| Professional ethics and sense of responsibility of construction workers (added) | |||

| Structures (Including Temporary Facilities) | Structural load-bearing capacity | 86.21% | Structural load-bearing capacity |

| Structural response (deleted) | 37.93% | Fall protection facilities for high-altitude operations | |

| Fall protection facilities for high-altitude operations | 93.1% | Emergency facilities | |

| Emergency facilities | 72.41% | Temporary electrical facilities | |

| Temporary electrical facilities | 72.41% | Temporary safety signs | |

| Temporary safety signs | 72.41% | Temporary traffic organization facilities (added) | |

| Drainage facilities (deleted) | 27.59% | ||

| Mechanical Equipment | Operating status of mechanical equipment | 79.31% | Operating status of mechanical equipment |

| Reliability of mechanical equipment | 89.66% | Reliability of mechanical equipment | |

| Lack or failure of safety devices | 93.1% | Lack or failure of safety devices | |

| Regular maintenance of equipment (added) | |||

| Environment | Hydrogeological environment | 86.21% | Hydrogeological environment |

| Site environment | 79.31% | Site environment | |

| Meteorological environment | 93.1% | Extreme weather (adjusted) | |

| Management | Safety education and training | 96.55% | Safety education and training |

| Safety supervision systems | 93.1% | Safety supervision systems | |

| Technical disclosure | 65.52% | Technical disclosure | |

| Emergency rescue plans | 89.66% | Emergency rescue plans | |

| Hidden danger investigation and remediation | 93.1% | Hidden danger investigation and remediation | |

| Emergency response capabilities | 86.21% | Emergency response capabilities | |

| Emergency drills (added) |

| Factor | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 | S8 | S9 | S10 | S11 | S12 | S13 | S14 | S15 | S16 | S17 | S18 | S19 | S20 | S21 | S22 | S23 | S24 | S25 | S26 | S27 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S5 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S7 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S8 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S9 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S10 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S11 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S12 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S13 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S14 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S15 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S16 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S17 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S18 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S19 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S20 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S21 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| S22 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| S23 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S24 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S25 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S26 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| S27 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| the set of triplets E∗ | (0.114,21,1),(0.114,22,1),(0.099,21,5),(0.099,22,5),(0.095,22,4),(0.094,21,4),(0.089,22,2),(0.088,21,2),(0.092,25,1),(0.086,23,1),(0.084,25,5),(0.079,23,5),(0.077,27,1),(0.074,7,5),(0.072,7,1),(0.071,20,1),(0.071,7,4),(0.069,21,7),(0.069,22,7),(0.069,27,5),(0.069,2,5),(0.068,2,4),(0.067,2,1),(0.067,9,1),(0.067,20,14),(0.066,4,5),(0.064,1,4),(0.064,1,5),(0.064,20,15),(0.064,22,24),(0.063,16,1),(0.063,19,1),(0.063,25,11),(0.063,25,12),(0.063,25,13),(0.062,20,9),(0.061,26,24),(0.060,3,6),(0.060,7,6),(0.060,27,26),(0.057,20,2),(0.056,25,2),(0.052,19,2),(0.051,19,4),… |

| the influence source set Ed | (21,22,21,22,22,21,22,21,25,23,25,23,27,7,7,20,7,21,22,27,2,2,2,9,20,4,1,1,20,22,16,19,25,25,25,20,26,3,7,27,20,25,19,19,21,21,22,22,21,21,22,22,21,27,19,21,22,22,27,5,12,18,21,3,21,21,21,22,22,22,25,26,27,6,13,18,19,19,20,21,22,25,6,18,18,18,18,19,19,20,20,21,22,24,24,24,25,25,25,17,17,17,18,18,18,19,19,19,20,22,27,7,8,10,11,12,13,15,15,16,17,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,23,23,23,23,23,25,27,24,26,20,20,19,26,27,20,27,27,27,27,22,24,24,…) |

| influence sink set Er | (1,1,5,5,4,4,2,2,1,1,5,5,1,5,1,1,4,7,7,5,5,4,1,1,14,5,4,5,15,24,1,1,11,12,13,9,24,6,6,26,2,2,2,4,11,13,11,13,10,12,10,12,9,24,9,14,15,23,4,1,1,14,23,5,16,17,24,16,17,25,7,10,25,5,5,15,14,15,10,19,19,10,1,1,10,12,13,13,16,17,8,16,25,25,10,11,13,8,9,23,1,2,14,8,16,17,8,16,17,18,22,22,2,1,2,2,2,2,2,14,2,14,15,19,18,19,21,21,8,9,10,11,…) |

| Value of Ed MDED set | 0.000, 0.000, 0.000, 0.000, 0.000, 0.000, 0.001, 0.001, 0.001, 0.001, 0.001, 0.001, 0.001, 0.006, 0.006, 0.010, 0.014, 0.012, 0.014, 0.011, 0.015, 0.015, 0.020, 0.019, 0.023, … |

| Value of Er MDER set | 0.000, 0.218, 0.175, 0.091, 0.075, 0.094, 0.064, 0.071, 0.068, 0.065, 0.072, 0.068, 0.055, 0.055, 0.059, 0.056, 0.048, 0.046, 0.044, 0.042, 0.030, … |

| Max MDED | 0.027 |

| Max MDER | 0.218 |

| λ | 0.041 |

| Factor | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 | S8 | S9 | S10 | S11 | S12 | S13 | S14 | S15 | S16 | S17 | S18 | S19 | S20 | S21 | S22 | S23 | S24 | S25 | S26 | S27 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S9 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S11 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S13 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S14 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S15 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S16 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S17 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S18 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S19 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S20 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S21 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| S22 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| S23 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S25 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| S26 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| S27 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Threshold Method | Threshold λ | Number of Layers | Differences in Hierarchical Structure | Interpretability Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMDE Optimization | 0.041 | 7 | Uniform hierarchical division with clear “source-process-terminal” logic | Optimal, consistent with the actual safety management process |

| Expert Subjective Determination | 0.052 | 5 | Unclear distinction among process guarantee factors | Good, but with the issue of subjective hierarchical compression |

| Mean + Standard | 0.037 | 8 | Excessive hierarchical segmentation | Poor, not conducive to prioritizing risk control |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, P.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, R.; Wu, B. Hierarchical Analysis for Construction Risk Factors of Highway Engineering Based on DEMATEL-MMDE-ISM Method. Sustainability 2026, 18, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010116

Zhang P, He Y, Zhang Y, Li R, Wu B. Hierarchical Analysis for Construction Risk Factors of Highway Engineering Based on DEMATEL-MMDE-ISM Method. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010116

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Peng, Yandong He, Yibo Zhang, Rong Li, and Biao Wu. 2026. "Hierarchical Analysis for Construction Risk Factors of Highway Engineering Based on DEMATEL-MMDE-ISM Method" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010116

APA StyleZhang, P., He, Y., Zhang, Y., Li, R., & Wu, B. (2026). Hierarchical Analysis for Construction Risk Factors of Highway Engineering Based on DEMATEL-MMDE-ISM Method. Sustainability, 18(1), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010116