1. Introduction

Shaft voltages and currents in electric machinery have long been recognized as critical factors contributing to equipment degradation and reliability loss in power generation systems [

1,

2,

3]. In large-scale turbine generators, unmitigated stray shaft currents can lead to electrical discharge machining (EDM) effects, such as bearing pitting, fluting, and accelerated wear, ultimately undermining the generator performance and increasing lifecycle maintenance costs [

4,

5]. To address this, shaft-grounding brushes (also referred to as earthing brushes) are conventionally employed to provide a controlled, low-impedance path to the earth, thereby diverting harmful currents away from sensitive components [

1,

6,

7,

8]. When operating correctly, these brushes support sustainable asset performance by minimizing energy losses, preventing catastrophic failures, and extending the operational lifespan of critical infrastructure [

7,

9,

10]. However, the degradation or improper contact of grounding brushes can result in an electrically “floating” shaft condition, allowing dangerous voltages to accumulate and discharge through unintended paths. Such failures can lead to increased energy consumption, unscheduled outages, and premature mechanical wear, all of which contradict the principles of sustainable and resilient energy systems. Ensuring the continued effectiveness of earthing systems is therefore essential for the reliable, efficient, and environmentally responsible operation of power generation assets.

Prior research has documented instances of generator failures due to insufficient shaft grounding and highlighted the importance of maintaining good brush contact [

5,

11,

12]. Early works analyzed shaft-induced currents in machines, and later investigations showed that large turbo-generators require robust grounding brushes for safe operations [

13,

14]. Grounding brushes for the safe operations of large turbine generators have been discussed as a critical safety measure in the literature [

4,

7,

8,

9,

13]. To address this, the continuous monitoring of shaft voltages and currents has been proposed as a means of obtaining early warnings of developing issues [

6,

10,

15,

16]. The authors of [

6] showed that by monitoring shaft voltages and grounding currents, incipient problems could be detected before total failure occurs. In recent years, there has been renewed research interest in bearing currents and shaft voltages in rotating machines, including comprehensive reviews of their causes, measurement techniques, and mitigation strategies [

1,

3,

5,

17,

18,

19,

20]. The authors of [

1] provide a detailed overview of shaft voltage and current measurement systems for large turbo-generators, reinforcing the need for improved diagnostic methods in this domain. Their review and others indicate that while many measurement approaches exist, practical case studies linking specific electrical signatures to particular fault types are scarce in the open literature.

The recent literature has increasingly emphasized the need for stronger links between theoretical shaft voltage models, laboratory investigations, and real-world observations from large turbo-generators. While prior studies have catalogued the mechanisms behind bearing currents, electrostatic charging, and grounding-brush behavior, only a limited number of works have translated these concepts into validated field diagnostics applicable to utility-scale machines. Reviews such as [

1,

11] highlight that although harmonic distortion, DC offset, and impulsive discharge events are well-understood phenomena in controlled environments, comprehensive, case-based evidence demonstrating how these signatures manifest under actual brush degradation, contamination, or grounding discontinuities remains scarce. This gap indicates a strong need for studies that combine rigorous signal analysis with confirmed in-service faults, thereby providing practitioners with actionable diagnostic patterns rather than purely theoretical descriptions.

In light of this, our work aims to bridge the gap between theoretical monitoring approaches and real-world fault diagnostics. The authors of [

21] demonstrated the feasibility of detecting different earthing-brush faults via shaft signal analysis on a small synchronous machine in a laboratory setup. The authors of [

11] further developed advanced diagnostic techniques for earthing-brush fault detection from shaft voltage and current measurements in large turbine generators through a series of controlled site tests on multiple turbo-generators, and the authors further demonstrated that distinct earthing-brush fault conditions produce measurable and characteristic changes in shaft voltages and currents.

Building on this foundation, this paper presents several operational case studies that illustrate how distinct faults in a generator’s shaft-earthing system manifest as observable patterns in voltage and current signals. We focus on four common fault scenarios: a floating voltage brush, a floating grounding brush, a worn (degraded) brush, and a contaminated brush (covered with oil and dust). For each case study, we compare baseline (healthy) measurements to the fault condition to highlight the changes in electrical signatures. The contributions of this work are as follows: (1) an empirical demonstration that advanced monitoring systems can detect subtle changes in shaft voltages/currents indicative of incipient faults; (2) identification of unique “electrical fingerprints” for different fault modes, enabling not just detection but also classification of the fault type; and (3) initial quantitative thresholds and trends that can guide alarm settings for practical monitoring systems.

2. Methodology and Experimental Setup

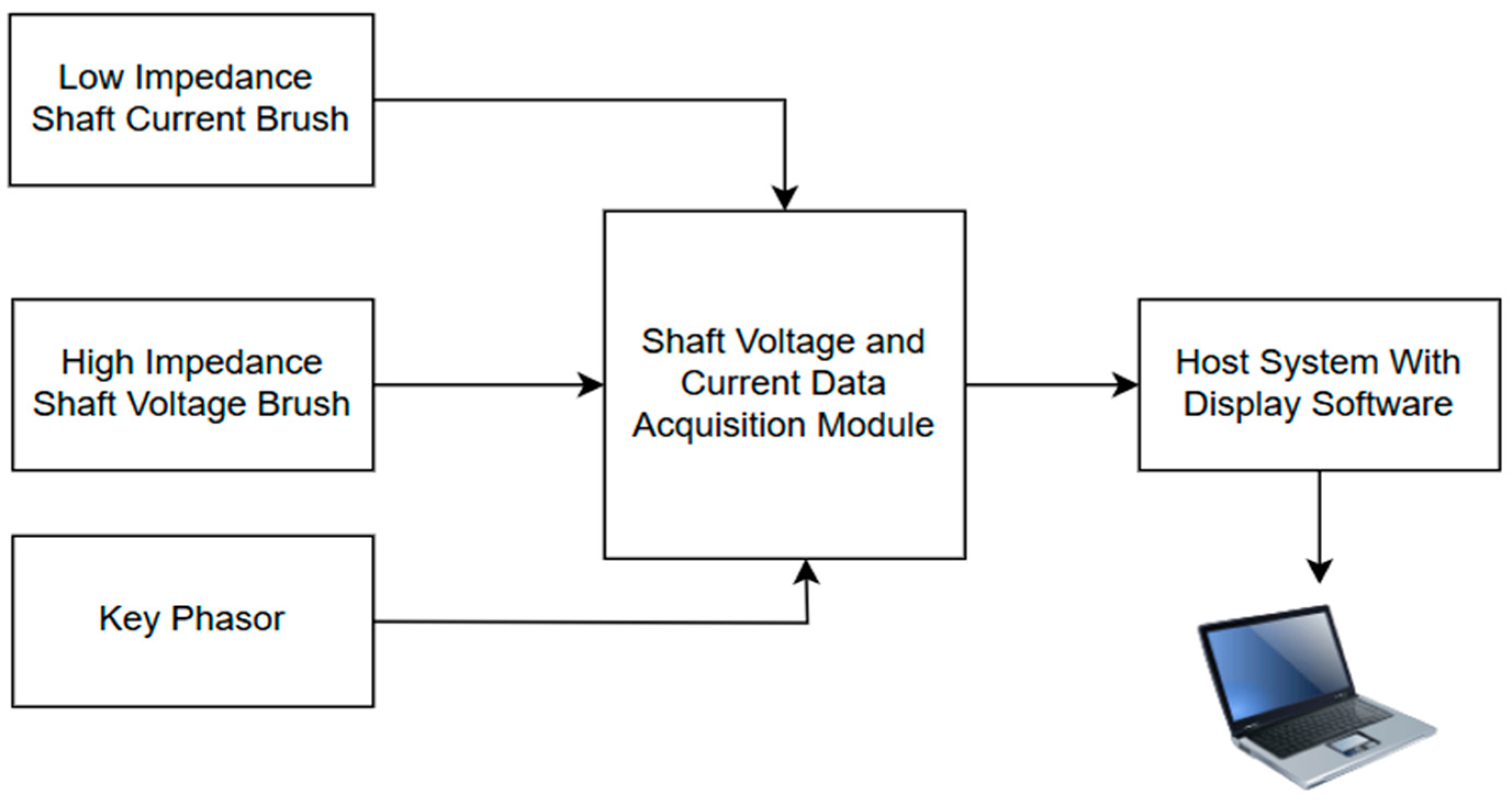

2.1. Online Monitoring System

An advanced shaft voltage and current-monitoring instrument was deployed on four large turbo-generators ranging from 246 MW to 713 MW. The system architecture is illustrated in

Figure 1. It employs three synchronized input channels: a high-impedance voltage brush, a low-impedance current brush, and a key-phasor signal providing a once-per-revolution reference.

Signals from both brushes are routed through a high-resolution data acquisition unit providing bandwidth up to 500 kHz—adequate to capture transients and harmonic components beyond the 50 Hz fundamental frequency. The processed data are transmitted to a host computer for real-time visualization and FFT-based analysis.

The latency requirements for identifying shaft-grounding faults are relatively modest because the diagnostic indicators RMS reduction, DC offset drift, harmonic distortion, and impulsive discharge activity develop over several electrical cycles rather than microseconds. The data acquisition unit used in this study (12-bit, 1 MS/s sampling rate) provides ample temporal resolution for detecting fast transient spikes and capturing harmonic components up to the high-frequency range. Although the DAQ is fully adequate for online diagnostic measurement campaigns, a permanent industrial monitoring installation would require automated near-real-time feature extraction to stream processed values such as the RMS, DC offset, and harmonic magnitudes directly to control room systems. Thus, the present DAQ supports accurate online detection, while continuous monitoring would require additional signal-processing integration.

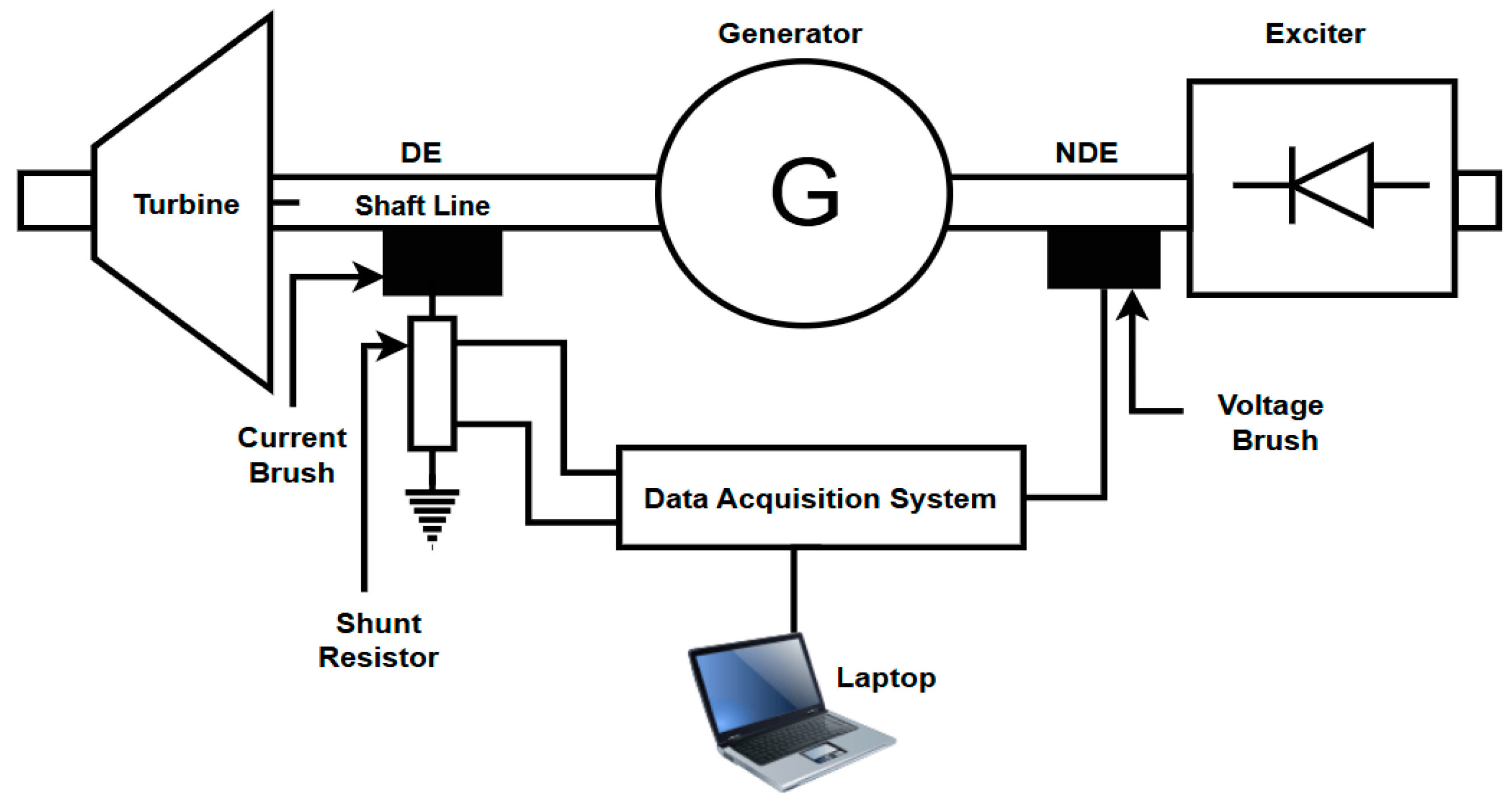

Figure 2 depicts a representative generator installation with the associated measurement instrumentation system. The non-drive-end (NDE) voltage brush senses shaft potential, while the drive-end (DE) brush provides a low-impedance grounding path through a calibrated 0.0496 Ω precision shunt (150 A, 1100 W). The voltage across the shunt yields the shaft current measurement. This configuration complies with IEEE 112 test method guidelines [

22], ensuring that the monitoring hardware does not alter the machine’s grounding behavior.

Prior to deployment, both measurement channels were calibrated. The shaft voltage channel was calibrated against a laboratory-grade multifunction calibrator (Fluke 5522A, Fluke Corporation, Everett, WA, USA) across the ±20 V input range, yielding a linearity error < 0.15% FS and a calibration uncertainty of ±0.05 V (k = 2). The shaft current channel uses a 0.0496 Ω precision shunt (±0.25% tolerance), and the voltage across the shunt was calibrated using a Fluke 8846A DMM (Fluke Corporation). The combined current measurement uncertainty was approximately ±0.3%, equivalent to ±0.01–0.02 A, over the current magnitudes encountered. These uncertainties are significantly smaller than the voltage and current deviations observed during the fault conditions analyzed in this study.

The 0.0496 Ω shaft current shunt is a low-inductance metal element device (≈10–20 nH, <1 pF parasitic capacitance). At 100 kHz, the inductive reactance is approximately 0.013 Ω, giving a total impedance of about 0.05 + j0.013 Ω. While this introduces some attenuation of the very short, high-frequency components of the current spikes, the measurement system is primarily sensitive to the presence, timing, and relative magnitude of impulsive discharge events, which are the phenomena of diagnostic interest. The analogue front-end bandwidth (≈500 kHz) further limits very-high-frequency components above ~200 kHz. Therefore, although parasitic inductance slightly reduces the absolute spike amplitude at frequencies > 100 kHz, it does not affect the ability of the monitoring system to detect or distinguish grounding-brush fault conditions.

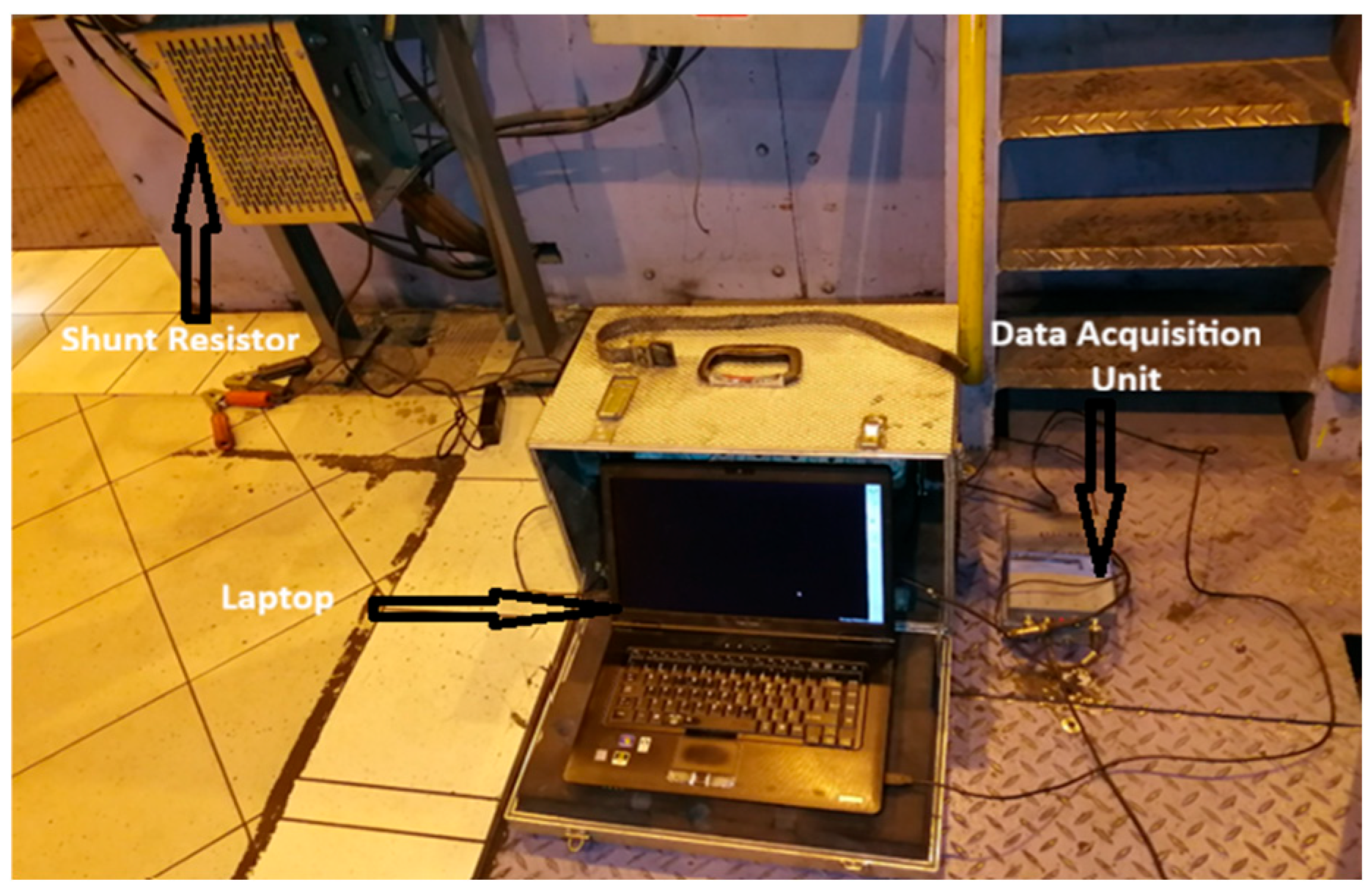

The photograph shows the complete on-site experimental setup used for the shaft voltage and shaft current measurement campaign, as shown in

Figure 3. A rugged industrial laptop serves as the main data-processing and visualization interface, connected directly to the high-resolution data acquisition unit (visible on the right). The DAQ unit receives signals from the voltage-sensing brush and the grounding-brush shunt resistor through shielded cables routed across the operating floor. The system is housed in a portable, protective case to withstand the harsh power station environment, and the components are arranged close to the generator pedestal to minimize noise pickup and signal attenuation. This field-deployable configuration enabled real-time monitoring, waveform capture, and FFT analysis during the in-service fault investigations.

2.2. Data Processing and Analysis

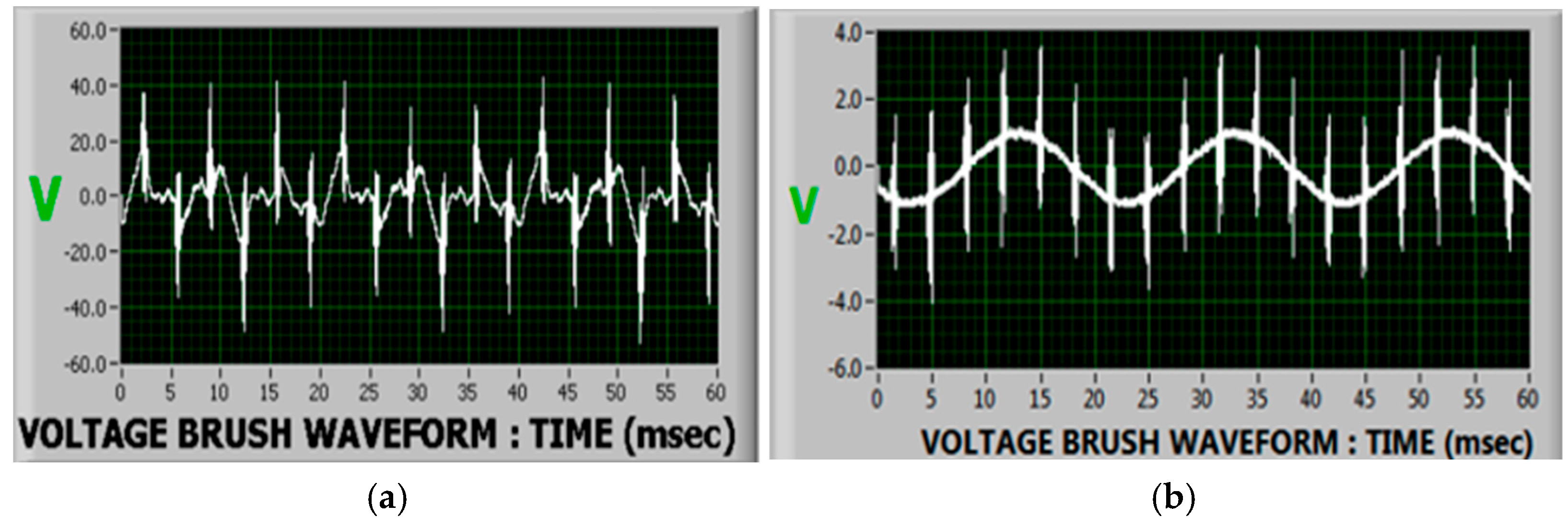

The voltage magnitudes reported in all tables (e.g., peak shaft voltage, RMS shaft voltage) were calculated directly from the digitally sampled waveform data (1 MS/s, 12-bit resolution). In contrast, the vertical-axis scales shown in the plotted figures (e.g., ±40 V in

Figure 4) represent the oscilloscope’s auto-selected display range and not the actual waveform amplitude. Therefore, the numerical peak values in the tables correspond to the true instantaneous shaft voltage, while the plotted figures may display a wider full-scale window for visualization purposes. Captured signals were analyzed in both the time and frequency domains as follows:

Time-domain analysis examined waveform distortion, amplitude excursions, and transient spikes.

Frequency-domain analysis used Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) techniques to determine harmonic content and total harmonic distortion (THD).

Time-domain discharge event plots.

Figure 4.

Power Station A shaft voltage brush waveform (V): (a) baseline vs. (b) floating voltage brush. Source: Authors.

Figure 4.

Power Station A shaft voltage brush waveform (V): (a) baseline vs. (b) floating voltage brush. Source: Authors.

Harmonic spectra were computed using Welch’s averaged periodogram method. A Hann window was applied to each data segment to minimize spectral leakage and preserve the fidelity of the fundamental and low-order harmonic components. Each spectrum represents the average of 16 overlapping segments (50% overlap), with an FFT length of 4096 samples at a 1 MS/s sampling rate, giving an effective frequency resolution of approximately 244 Hz. This averaging procedure reduces random noise and stabilizes the harmonic signatures, which is important when comparing baseline and fault conditions in the presence of impulsive disturbances.

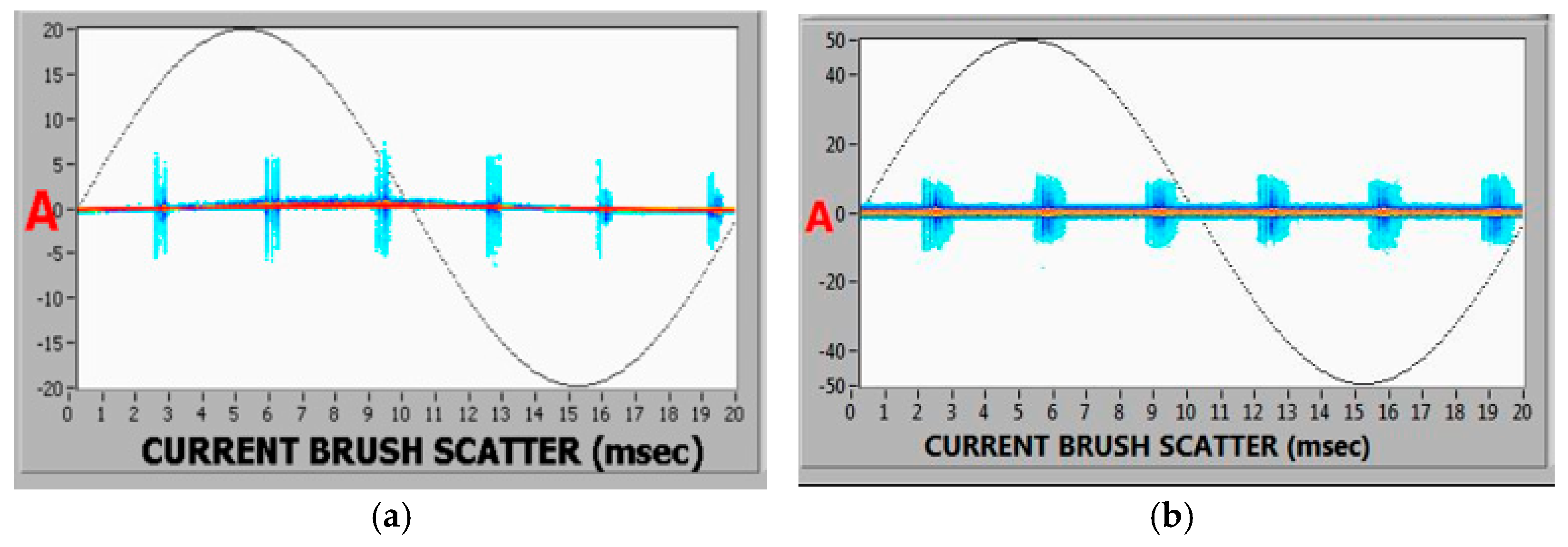

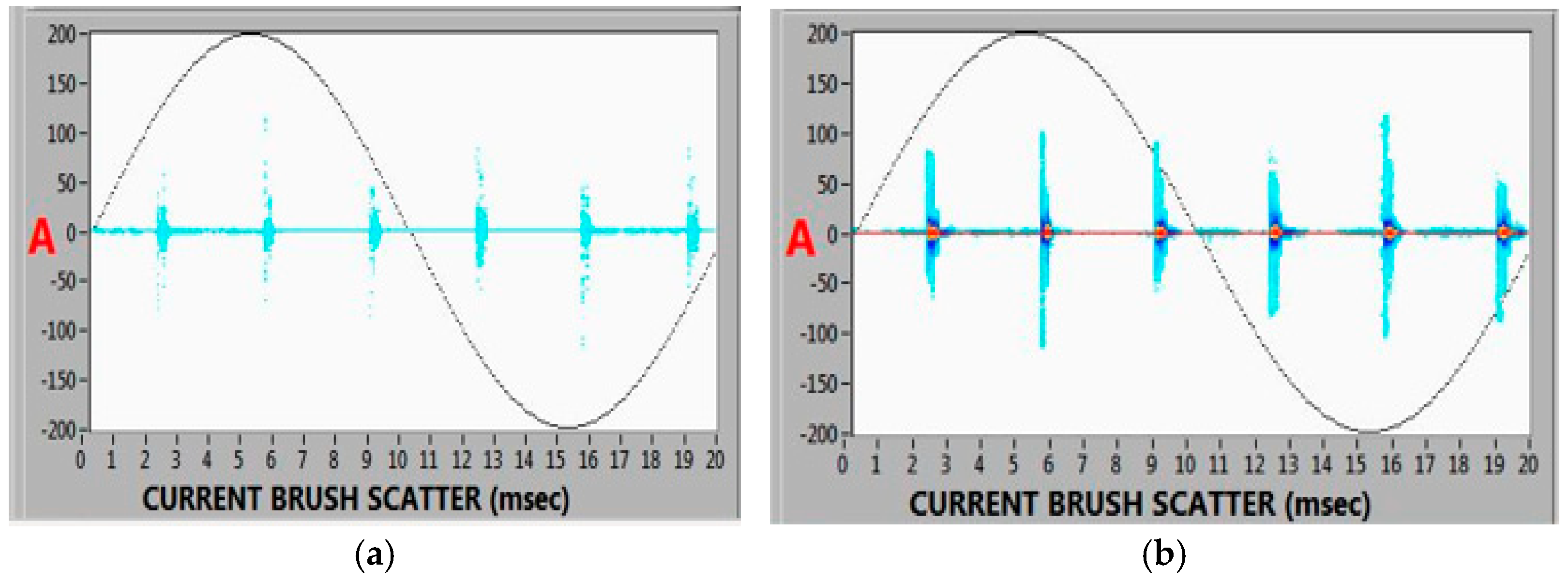

Although the platform supports the scatter-plot analysis of instantaneous currents versus electrical phase angles, the figures presented in this manuscript (

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8) show time-domain shaft current traces plotted as current amplitudes versus time (ms). These time-domain plots were chosen because they more clearly highlight intermittent discharge spikes, arcing behavior, and contact instability during the fault conditions. A 50 Hz sine wave is included in these figures as a reference signal to illustrate deviations from an ideal fundamental waveform and to help identify the timing of the discharge events.

The shaft voltage and current signals were digitized using a 12-bit data acquisition unit operating at 1 MS/s. The analogue front-end scales the shaft voltage to a ±20 V full-scale input, giving a quantization step size of approximately 9.8 mV per least significant bit (LSB). The worst-case quantization error is therefore ±0.5 LSB (≈±4.9 mV), which is an order of magnitude smaller than the smallest DC offsets of interest (≈0.1 V). Since DC and RMS values are computed by averaging over many samples and main cycles, the effective uncertainty due to quantization is further reduced. Consequently, the DC offset and RMS variations reported in this work lie well above the quantization noise floor and can be resolved reliably by the monitoring system.

Data were compared between baseline (healthy) and fault conditions for each case study. Quantitative metrics included the RMS peak, RMS average, and DC offset for both voltage and current.

Direct measurement of brush–shaft contact resistance using a micro-ohmmeter was not always feasible during online operation. However, during maintenance inspections, the brush surface condition, spring tension, landing geometry, and contamination film were examined to infer the contact resistance qualitatively. The waveform distortions observed in this study, such as RMS voltage collapse, DC offset drift, non-periodic voltage behavior, broadband harmonic noise, and intermittent high-current spikes, correlate strongly with the expected variations in contact resistance. In floating or worn brushes, intermittent loss of contact produces sharp transient discharges and unstable conduction, whereas contamination produces moderately elevated and time-varying resistance that leads to increased DC bias and erratic current pulses.

2.3. Test Units and Operating Conditions

Table 1 summarizes the key parameters of the turbine generator units tested. All are two-pole machines ranging from 246 MW to 713 MW and between 36 and 54 years of service, representing a diverse cross section of the utility’s generation fleet. Each unit was monitored under steady-state load conditions. Fault scenarios were investigated and observed during in-service anomalies.

3. Case Studies and Test Results

This section presents four representative operational case studies that illustrate distinct fault modes in turbo-generator shaft-earthing systems. For each, time-domain, frequency-domain, and scatter-plot analyses were performed to identify characteristic electrical signatures.

Although direct micro-ohm measurements of the brush contact resistance were not taken during online operation, physical inspection during maintenance allowed for qualitative estimation based on the brush wear, spring pressure, glazing, and contamination. The waveform distortions reported in each case (RMS collapse, DC offset increase, non-periodic behavior, and current surges) are consistent with the theoretical effects of increased or unstable contact resistance. Floating brushes correspond to effectively infinite resistance, worn brushes produce fluctuating resistance, and contaminated brushes exhibit moderately elevated and variable resistance.

3.1. Operational Case Study #1: Floating-Voltage-Brush Fault (Station A)

The Station A Unit (400 MW, 54 years of service) was found to have abnormally high shaft voltage readings during routine monitoring. Investigation revealed that both voltage brush holders on the exciter end had become mechanically loose, due to weakened spring pressure. This caused one of the voltage-sensing brushes to lose consistent contact with the shaft, effectively a floating-voltage-brush condition. The machine continued to operate, but with the brush intermittently not touching the shaft. This fault was confirmed by physical inspection of the brush assembly (the faulty brush holder mechanism is shown in

Figure 9).

To supplement the qualitative harmonic spectra presented in

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8,

Table 2 provides numerical harmonic indices for the second, third, fifth, and seventh shaft voltage harmonics under both baseline and fault conditions for all four case studies. These harmonic indices were derived by visually ranking the relative magnitudes of the FFT components within each spectrum, using a normalized scale (0–5) due to the absence of absolute Y-axis values in the exported DAQ figures. Although the plotted FFT images do not preserve numeric vertical scaling, the relative changes in harmonic strength remain diagnostically meaningful.

Table 2 therefore provides a consistent, quantitative comparison of the harmonic behavior across the four generator fault modes.

When the voltage brush was floating, the shaft’s charge could no longer dissipate normally through the high-impedance path of that brush. The immediate effect was a drastic change in the shaft voltage waveform.

Figure 4 compares the shaft voltage waveforms for the baseline versus floating-brush condition. Under the fault, the RMS voltage collapsed from 6.70 V to 0.78 V, while the peak voltage spiked from 6.8 V to 24.7 V. The waveform became erratic, dominated by transient discharges rather than a smooth sinusoid.

Table 3 quantifies these values.

The simultaneous decrease in the RMS voltage and increase in the peak voltage is a characteristic signature of intermittent brush contact. When the voltage brush is partially floating, the shaft voltage remains near zero for most of each cycle because charge is no longer transferred continuously to the measurement circuit. This drives the RMS value down, since the RMS reflects the average energy content of the waveform. However, as charge accumulates on the shaft, brief reconnection events occur, producing short-duration, high-amplitude discharge spikes. These impulsive transients contribute very little to the RMS value due to their narrow width but strongly influence the peak voltage. As a result, the RMS collapses while the instantaneous peak can rise dramatically, reflecting a transition from steady sinusoidal behavior to sporadic arcing-type discharges.

The floating-voltage-brush behavior can be interpreted using a simple lumped RC model. The generator shaft is represented as a conductor with finite capacitance (

) to ground, supplied by a small charging current (

) associated with induction and stray capacitive coupling in the excitation system. When the voltage brush is not in contact, the shaft is connected to ground only through a large leakage resistance (

), so the shaft voltage (

) builds up and gradual charges towards an equilibrium voltage. The shaft voltage then evolves according to the following:

with solution

(

t) =

, where

and (

). Thus, during each “open” interval, the shaft voltage gradually accumulates towards an equilibrium value set by the charging current and leakage path.

When contact is briefly re-established, the effective resistance collapses to a low value (

, and the governing equation becomes

and a very short discharge time constant (

). The resulting charge–accumulate–discharge cycle produces long intervals of low voltage interspersed with brief, high-amplitude spikes, which explains why the RMS voltage collapses while the instantaneous peak voltage and dV/dt increase during the floating-brush fault.

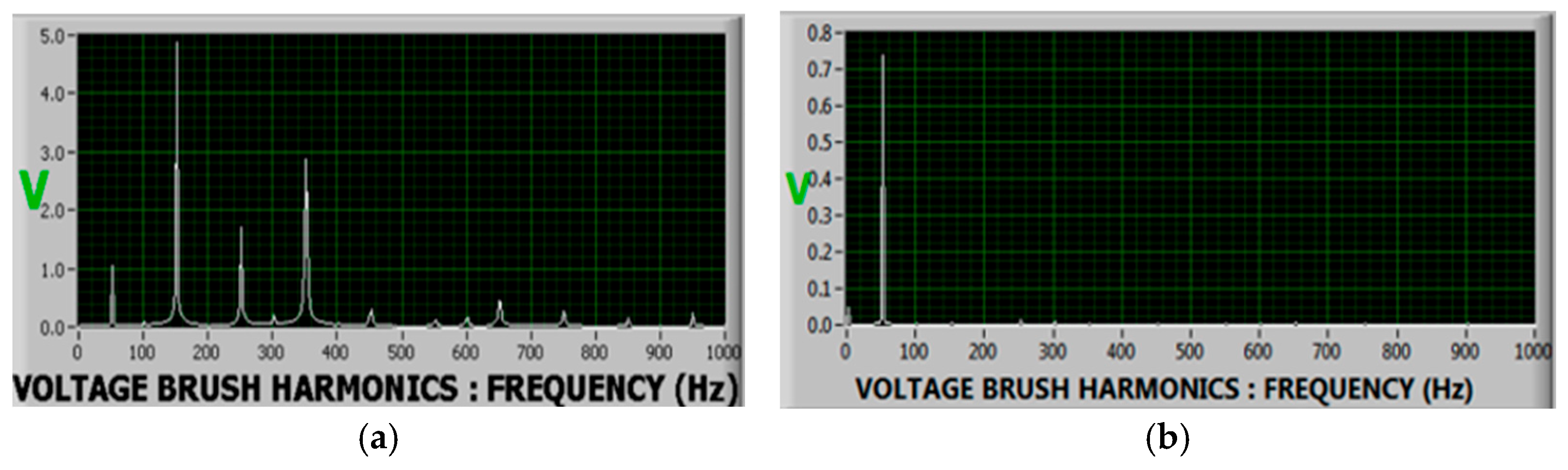

The frequency-domain analysis reinforces this observation. The voltage FFT spectrum (

Figure 4) showed that many of the normal harmonic components were greatly attenuated or disappeared when the brush floated. As seen in

Figure 5, the FFT spectrum lost its structured harmonic profile (notably the 150 Hz and 350 Hz components) and was replaced by broadband noise evidence of intermittent discharge rather than continuous conduction.

Crucially, the shaft-grounding current surged during the floating-brush condition.

Figure 10 presents scatter plots of shaft currents for baseline vs. fault conditions. With one voltage brush floating, the average shaft current found alternate paths (likely through the remaining grounding brush or even through bearings). The fault condition showed significantly higher and more erratic current values. The peak current rose from high resolution ones 0.39 A to 6.60 A, and the RMS current rose from 0.30 A to 2.31 A (

Table 4). This >10-fold increase indicates that charge was discharging through alternate unintended paths, such as bearings or coupling joints. Under baseline conditions (

Figure 10a), the blue waveform appears compact and low in amplitude, indicating stable grounding and consistent charge dissipation. In the floating-brush condition (

Figure 10b), both the blue instantaneous trace and the red RMS envelope become widely dispersed, with frequent sharp spikes. These coloured clusters particularly the dense red regions highlight periods of elevated current density caused by intermittent electrical contact. The irregular, high-amplitude excursions reflect transient discharge events through unintended paths such as bearings or coupling interfaces. This broadened distribution and the appearance of high-density colour clusters are characteristic of grounding failure, where the floating brush reconnects sporadically and produces EDM-like current surges.

A floating voltage brush produces a collapse in the average shaft voltage, loss of harmonic order, and sharp current surges. Meanwhile, the grounding current increases dramatically through unintended paths. Without prompt detection and correction (e.g., re-tensioning or replacing the brush), this condition can result in rapid bearing damage due to spark erosion and insulation stress. Collectively, these effects drastically increase the likelihood of insulation stress, electrical erosion, and premature generator component failure. The findings underscore the importance of reliable mechanical brush-holder systems and continuous online monitoring to prevent undetected floating-brush conditions.

3.2. Operational Case Study #2: Floating-Current-Brush Fault (Station B)

In the Station B Unit (713 MW, 40 years of service), an incident occurred where the shaft-earthing (current) brush became electrically disconnected. This unit uses a brush at the drive end as the primary low-impedance path to ground. The fault was initially indicated by abnormally high shaft RMS current readings and was later traced to a loosened or detached cable connecting the current brush to the ground mat (essentially an open circuit in the main grounding path). This floating-current-brush condition was confirmed via maintenance inspection.

Figure 11a shows the dislodged brush cable, and

Figure 11b displays evidence of electrical arcing/pitting damage on a generator bearing, consistent with circulating currents passing through it during the fault. Once the brush cable was reconnected, normal grounding was restored, allowing comparative measurements between the faulty and healthy states.

In the faulted conditions, especially in Cases 1 and 2, the loss of a stable grounding path allows for a substantial portion of the shaft current to circulate through bearings and other unintended structures, where the associated power loss can be approximated as follows:

Although the bearing current and film resistances were not measured directly in this study, the observed >10-fold increase in the peak and RMS shaft currents during the faults, followed by a return to low and stable currents once proper grounding was restored, implies a corresponding order-of-magnitude reduction in the electrical energy available to drive EDM damage when grounding is healthy. The present results therefore support the qualitative conclusion that stable shaft grounding markedly reduces bearing power dissipation and erosion risk, even though precise numerical values of the bearing power loss could not be quantified with the available instrumentation.

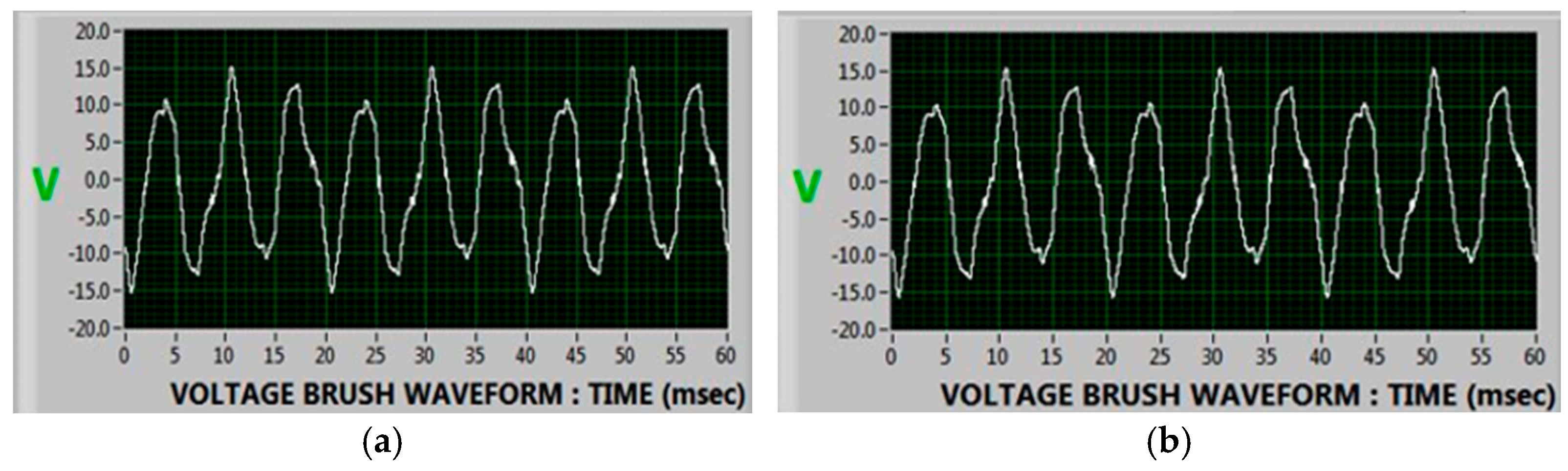

In contrast to Case 1, here, the shaft voltage did not collapse; instead, it remained at levels similar to the baseline amplitude, since the voltage-sensing brush was still in place, providing a reference. However, the nature of the voltage waveform changed under the floating-current-brush condition.

Figure 12 shows that the shaft voltage waveform amplitude remained ≈8 V, yet a pronounced DC offset appeared (from 0.23 V to 0.69 V). The RMS magnitude stayed nearly constant (7.9 V), confirming that voltage monitoring alone would not expose this failure.

The reason the shaft voltage RMS remains almost unchanged during the floating-current-brush fault is that the rotor is still capacitively coupled to ground through several distributed paths, including air-gap capacitance, stator-to-rotor capacitance, excitation system capacitance, and parasitic coupling through bearings and shaft seals. These high-impedance capacitive networks continue to impose an approximately sinusoidal voltage on the shaft, even when the main low-resistance grounding brush is electrically open. As a result, the overall RMS voltage stays close to the baseline value. What changes instead is the symmetry of the waveform: loss of the current brush introduces a net DC bias and enhances even-order harmonics, reflecting asymmetric charge–discharge behavior across the capacitive leakage network. This behavior is consistent with a shaft that remains capacitively energized while losing its primary resistive grounding path.

Table 5 quantifies these values. This DC shift in the shaft voltage indicates an asymmetry in the discharge of electric charge on the shaft. Essentially, without the low-resistance current brush, the shaft was “charging up” slightly, and current only flowed in bursts when the voltage brush or other leakage paths allowed it, leading to a net DC accumulation between discharges.

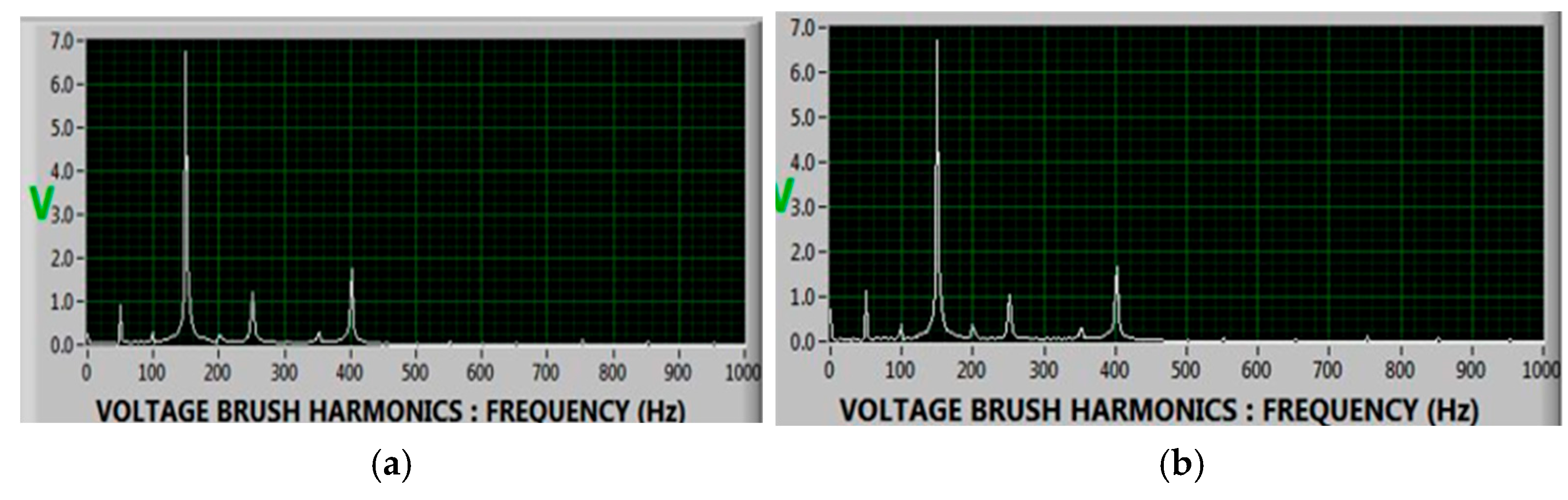

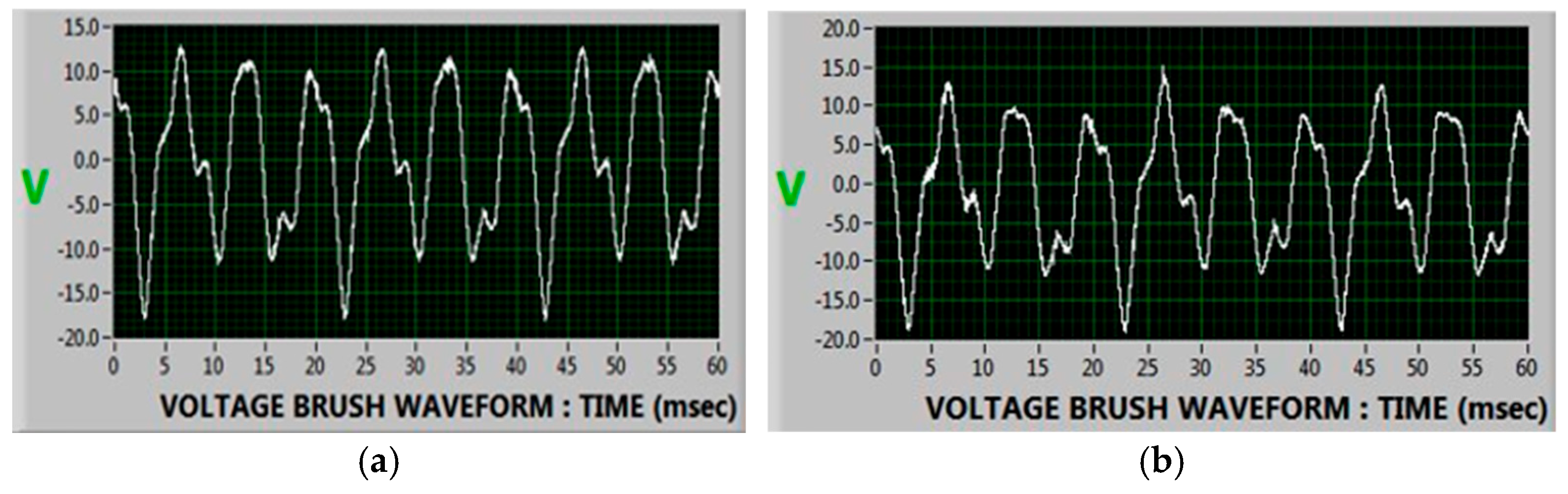

Frequency-domain analysis (

Figure 6) revealed a strong presence of even-order harmonics in the shaft voltage during the fault. Specifically, components at 100 Hz, 200 Hz, etc., became pronounced, growing DC components typical of asymmetrical, rectifying conduction. A floating current brush manifests as DC bias > 0.1 V, emergence of even harmonics, and a decline in the measured shaft current magnitude. The DC offset threshold (≈0.2 V) is a reliable trigger for grounding-integrity alarms. Immediate correction prevents severe EDM damage.

Figure 13 presents scatter plots of shaft currents for baseline vs. fault conditions. Measured currents through the shunt dropped from 0.63 A to 0.46 A, as shown in

Table 6, confirming loss of the main low-impedance path, while unmeasured stray currents caused bearing pitting (confirmed by inspection). Under normal operation (

Figure 13a), the blue current trace remains tightly bounded, indicating stable grounding and controlled dissipation of shaft charge. In contrast,

Figure 13b shows that the floating-brush waveform becomes highly irregular, with both the blue instantaneous trace and the red RMS envelope displaying sharp transients and widened amplitude spread. The clustered red regions represent periods of elevated current density caused by intermittent brush contact, while the scattered blue spikes reflect unstable, high-frequency discharge events. This broadened colour distribution indicates that the grounding path is intermittently forcing charge through unintended conductive routes—such as bearings or couplings—thereby increasing the likelihood of repetitive EDM activity. The observed instability confirms that floating-brush conditions significantly weaken grounding performance and elevate the risk of progressive bearing and insulation damage.

In summary, the floating-current-brush fault produced a stable average shaft voltage with a significant DC bias, dramatic rises in transient shaft current spikes (through unintended paths) accompanied by a drop in steady measured current through the normal path, and a loss of harmonic stability in the voltage signal. This led directly to bearing arcing damage. The incident underlines the need for robust grounding-integrity checks and real-time alarms for any discontinuity in the earthing circuit, as well as highlights the critical role of the continuous monitoring not only of shaft voltages but also of shaft currents in detecting floating-current-brush conditions. It also highlights the importance of robust grounding-integrity checks and the periodic verification of earthing connections to prevent recurrence.

3.3. Operational Case Study #3: Worn-Brush Fault (Station C)

The Station C Unit (246 MW, 48 years of service) began showing signs of an irregular shaft-grounding performance during operation. Operators observed visible sparking at the drive-end earthing brush during operation, and the shaft RMS peak current reading was abnormally high. Initial electrical checks (insulation resistance and continuity of the brush cable to ground) appeared normal, suggesting that the grounding path was intact. However, upon inspection during a scheduled outage, the grounding brush was found to be severely worn and near end-of-life. The brush contact surface was uneven and significantly shortened, resulting in poor contact pressure against the shaft. The shaft surface itself had slight engraving marks, a sign of prolonged operation with an intermittently contacting brush. Essentially, this case represents a worn-out brush that had degraded to the point of unstable electrical contact (

Figure 14).

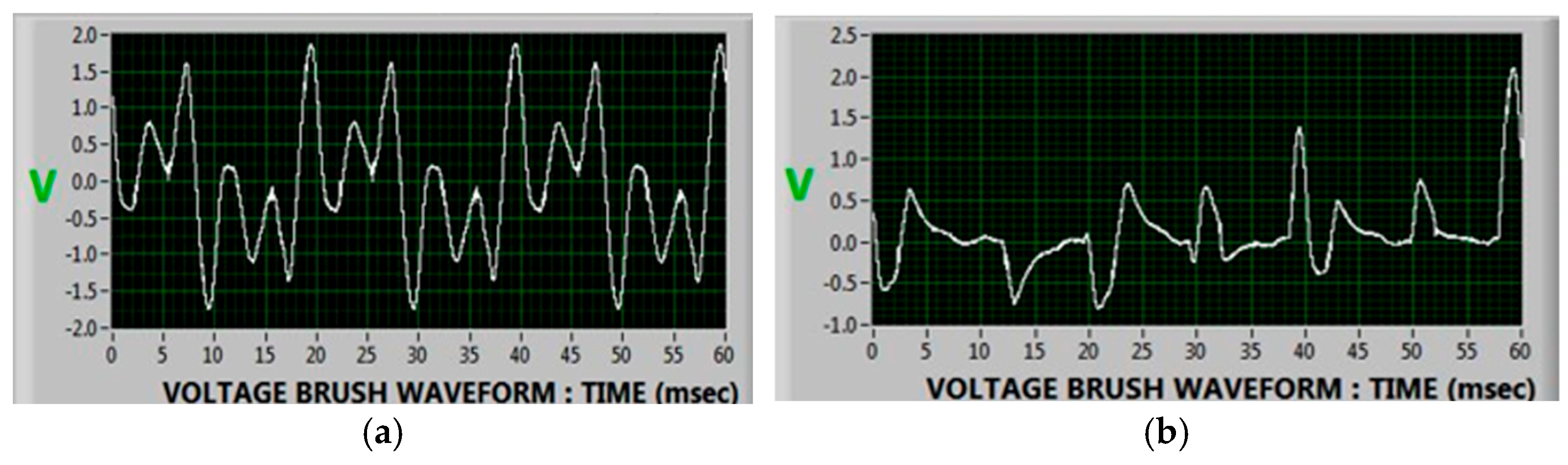

A worn brush introduced an extremely unstable electrical connection.

Figure 15 compares the shaft voltage waveform for the baseline (new brush) versus worn-brush condition. With the worn brush, the voltage waveform became highly distorted and erratic. Instead of a clean sinusoid, the voltage was noisy and frequently dropped out.

Figure 15b shows a non-periodic voltage waveform due to the worn-brush condition. The brush intermittently loses contact with the shaft, producing irregular discharge events, arcing pulses, and sudden voltage spikes (e.g., the 2 V peak at 55–60 ms). Unlike healthy conditions where the waveform is periodic at 50 Hz, a worn brush generates a non-stationary signal with cycle-to-cycle variation. In such cases, the FFT is interpreted as a broadband distortion spectrum rather than a harmonic profile, reflecting the unstable electrical contact characteristic of brush degradation.

Unlike the fully floating-voltage-brush condition in Case 1, a worn brush does not completely lose electrical contact for long intervals. Instead, the brush maintains intermittent or partial contact, with momentary conduction occurring whenever the remaining carbon surface touches the shaft. This partial contact provides a high-resistance but still functional leakage path that continuously bleeds off accumulated charge. Consequently, the shaft voltage cannot rise to the much higher potentials seen in fully floating conditions, and the resulting discharge events are smaller in amplitude. The worn-brush fault therefore produces frequent low-energy discharges rather than the infrequent high-energy spikes characteristic of a completely floating brush. This behavior limits peak voltage but increases waveform irregularity and harmonic noise.

The average voltage level at the brush dropped dramatically. In fact, during the worst moments of poor contact, the measured shaft voltage would collapse toward zero for brief intervals (essentially when the brush momentarily lost contact entirely). Quantitatively, there was a substantial reduction in the effective (RMS) voltage and a noticeable introduction of the DC component due to asymmetrical discharge. From

Table 7, we see that one measure of the shaft voltage’s RMS value decreased from ~0.86 V (the baseline healthy value for this particular unit) to ~0.41 V with the worn brush, reflecting the loss of consistent conduction. Meanwhile, a small DC offset appeared, rising from virtually 0 (0.01 V baseline) to ~0.07 V under the worn condition, indicating intermittent rectification effects as the contact repeatedly breaks and reconnects. Interestingly, the peak voltage did not increase in this case (remaining around 0.9 V; note that Station C’s absolute shaft voltage levels are lower than those of Stations A and B due to differences in the excitation and machine size). The lack of high-voltage spikes suggests that the brush, while sporadic, was still usually in contact enough to bleed off charge before very large voltages accumulated; however, it was making and breaking contact so rapidly that the voltage never built up to extreme spikes, as in Case 1.

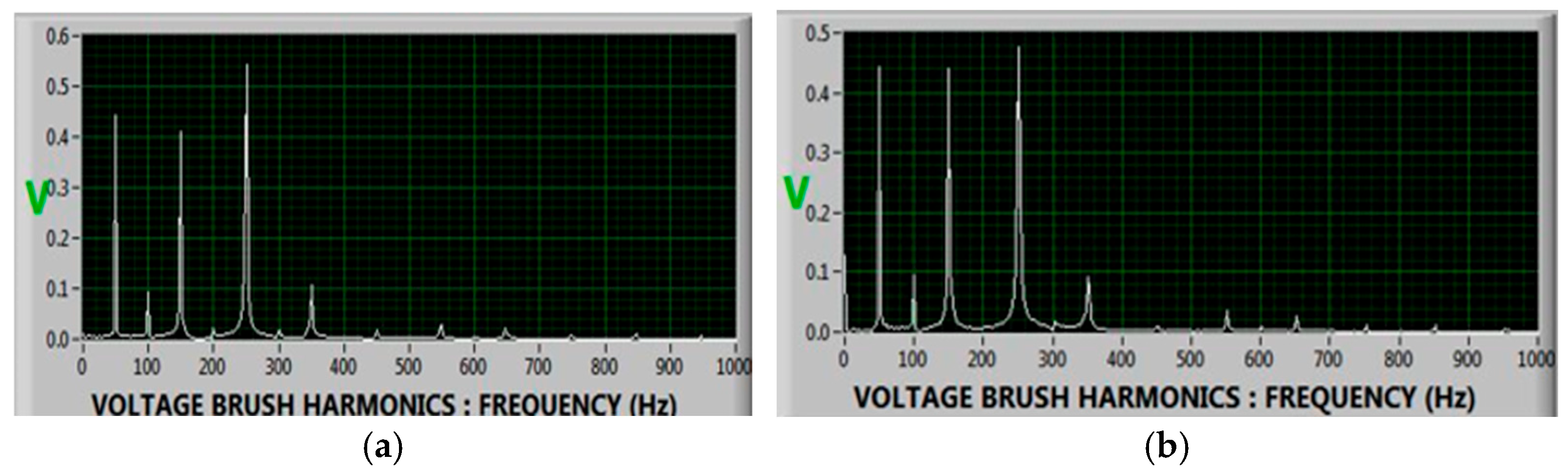

The FFT harmonic analysis (

Figure 7) shows a broadband spectrum containing both odd and even harmonics with an elevated noise floor, reflecting unstable, arcing contact. Unlike the floating current brush in Case 2, a worn brush introduces a fluctuating impedance: sometimes conducting, sometimes arcing. This produces a spectrum with many frequency components. In our data, higher-order harmonics were generally reduced in amplitude (since the stable driving waveform is compromised), but a wide range of low- and mid-frequency harmonics were present at modest levels, and the spectrum did not exhibit the clean discrete peaks of the baseline. The presence of simultaneous odd and even harmonics, plus a DC component, is characteristic of erratic, nonlinear contact.

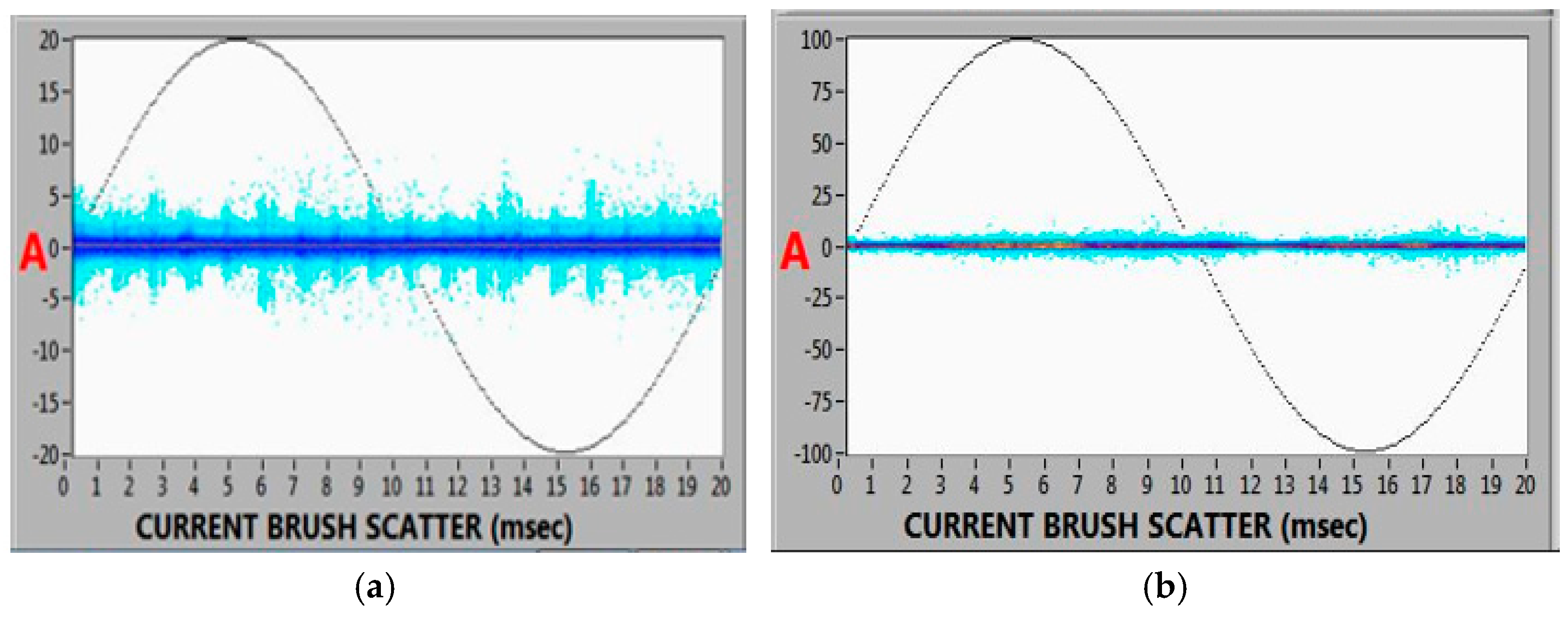

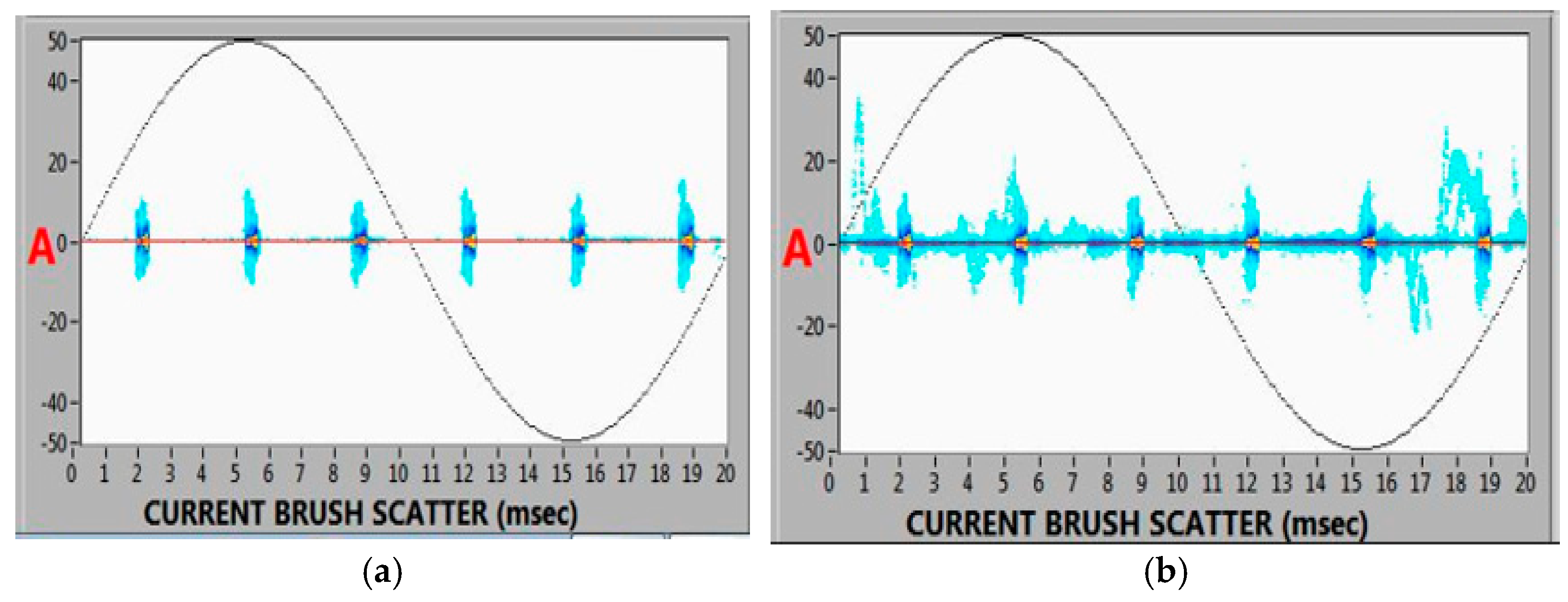

The shaft current under the worn-brush condition was perhaps the most telling indicator.

Figure 16 (current scatter plot) reveals an order-of-magnitude increase in the current variability. In other words, while the average grounding current for this unit might normally be a few amps, with the worn brush, it occasionally surged to several times that value in bursts. From

Table 8, the peak current observed increased from about 3.44 A (baseline) to 8.19 A with the worn brush. The RMS current also rose slightly (from ~3.29 A to 3.43 A), but this small change masks the real issue: the current was not steady. Instead, it oscillated between near-zero and very high spikes. Each time the brush made momentary contact after a brief open interval, a surge of charge flowed (essentially discharging the accumulated shaft voltage), resulting in a sharp current pulse. Then, as the brush lifted or had high resistance, the current dropped off again. This cycle repeated continuously, producing a noisy current signal with large excursions. Under baseline conditions (

Figure 16a), the blue shaft-current trace remains stable and well-bounded, indicating continuous and reliable conduction to ground. In contrast, the worn-brush condition in

Figure 16b shows a highly erratic pattern, with both the blue instantaneous waveform and the red RMS envelope exhibiting frequent high-amplitude spikes and periods where the current collapses to near zero. The scattered blue peaks and dense red clusters reflect intermittent brush contact: when resistance increases due to wear, the shaft accumulates charge, and when contact is momentarily restored, the charge is released in sharp current surges. This colouring pattern highlights the unstable grounding behaviour characteristic of worn brushes and indicates elevated risk of discharge events, heating, and brush–rotor interface degradation.

A worn-out brush can in some ways be more insidious than a completely failed brush because it intermittently provides a path to ground. This intermittent conduction means that the system experiences the worst of both worlds: periods of ungrounded operation (risking voltage buildup) interspersed with sudden high current discharges when contact is re-established. Operationally, this condition greatly increases the risk of localized heating, arcing damage at the brush–rotor interface, and even unexpected protection trips (if currents spike high enough or cause sensor noise). The findings reinforce why utilities typically replace brushes well before they reach complete wear-out: as the brush shortens and spring pressure weakens, its performance deteriorates nonlinearly. The monitoring system successfully detected this degradation by noting the increase in harmonic noise and erratic current behavior even before a total failure occurred. Thus, it provides an early warning for maintenance intervention (e.g., brush replacement) prior to a potentially catastrophic loss of grounding.

In conclusion, for Case 3, the worn-brush fault resulted in severely distorted voltage waveforms, a mix of odd/even harmonics and DC bias in the voltage spectrum, and highly irregular grounding currents with frequent surges. These signatures serve as clear indicators of a degraded brush that requires immediate replacement.

3.4. Operational Case Study #4: Brush Contamination Fault (Oil/Dust) (Station D)

The Station D Unit (approximately 600+ MW class, brushless excitation) experienced a subtler fault mode: contamination of the shaft grounding brush with oil and dust. Over time, oil mist from a slight seal leakage had mixed with carbon dust from the brush, forming a film layer on the brush shaft surface. This condition often goes unnoticed until it manifests as performance issues. In this case, routine online monitoring flagged anomalous waveform patterns and unexpectedly or abnormal high peak and average shaft currents on Unit 5 of Station D during steady-state operation. Upon checking the shaft-earthing assembly, maintenance technicians found the earthing brush and its holder coated with a layer of oily carbonaceous and pulverized fuel residues, as shown in

Figure 17. This contamination was providing an unpredictable electrical interface that was sometimes insulating, sometimes partially conductive. The brush and journal landing were thoroughly cleaned afterward, restoring normal readings.

To further assess the insulation-stress severity, the maximum voltage and current slew rates were evaluated qualitatively for all case studies. Since absolute numerical slew rates cannot be recovered from the exported DAQ images, a normalized 0–5 index scale was used to compare the relative steepness and impulsiveness of voltage and current spikes across faults.

Table 9 summarizes the comparative maximum dV/dt and dI/dt behavior for baseline and fault conditions.

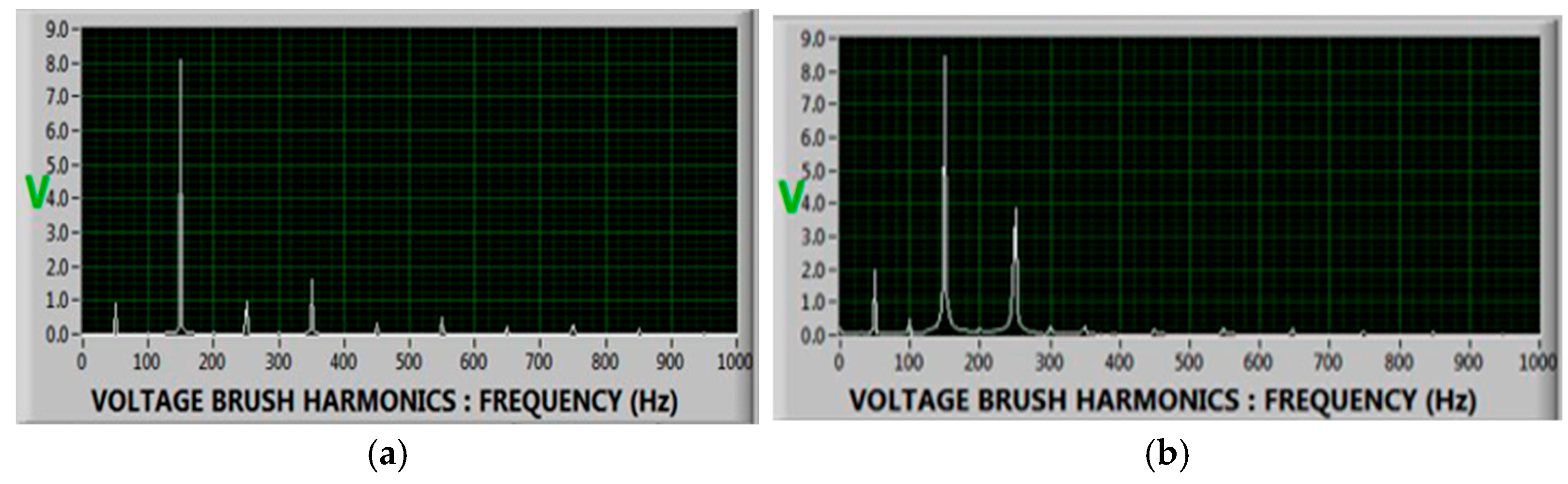

Brush contamination presented a distinctive signature compared with the purely mechanical faults.

Table 10 shows that the overall shaft voltage amplitude remained nearly unchanged under contamination. The RMS peak voltage increased only slightly, from 8.22 V (baseline) to 8.54 V, while the RMS average also rose modestly from 8.08 V to 8.52 V. However, the DC component increased sharply, from 0.12 V to 1.07 V. This indicates that while the voltage brush could still capacitively couple to the shaft through the contamination layer, the insulating film introduced a sustained DC bias and compromised the waveform stability. The contaminated interface likely caused intermittent sticking or insulating behavior, visible as minor irregularities in the voltage trace.

Figure 18 shows that the shaft voltage waveform became distorted under contamination, and a measurable DC offset appeared. The pronounced DC offset observed in the oil/dust contamination case can be explained by the semi-conductive film that forms on the shaft–brush interface. The mixture of oil mist and carbon dust creates a thin, uneven, partially insulating layer with nonlinear electrical properties. This layer behaves similarly to a

half-wave rectifier: it permits charge transfer more readily during one polarity of the shaft voltage cycle while impeding conduction during the opposite polarity. The resulting asymmetric conduction distorts the waveform, suppresses one half-cycle, and introduces a net DC shift. This rectification-like behavior is characteristic of contaminated sliding contacts and explains the elevated DC component and the presence of enhanced even-order harmonics in the voltage spectrum.

The shaft current response, by contrast, changed much more dramatically (

Figure 19,

Table 11). The RMS peak current rose from 0.58 A to 3.78, a more than sixfold increase, while the RMS average current more than doubled, from 0.44 A to 0.97 A. This reflects highly erratic conduction at the brush–shaft interface: when the oil/dust film temporarily increased contact resistance, the shaft accumulated excess charge, which was then released as sudden high-current surges once a conductive path formed. These frequent discharge events produced a widened scatter of current values and spiky current waveforms, highlighting an unstable grounding performance. Under baseline conditions in

Figure 16a, the time-domain current trace exhibits a compact and uniform pattern, represented by a narrow band of points indicating steady conduction to ground. In contrast, the contaminated-brush waveform in

Figure 16b displays a broad, irregular spread of amplitudes, with the colouring in the scatter distribution highlighting clusters of high-density current spikes. These coloured clusters correspond to periods where the brush momentarily regains electrical contact after slipping into a high-resistance state due to the contamination film. When the brush lifts or the oil/dust layer increases resistance, the shaft accumulates charge; upon sudden reconnection, this charge discharges in sharp bursts, producing the brightly coloured high-amplitude regions and elongated streaking visible in the plot.

In essence, contamination did not significantly alter the RMS shaft voltage magnitude, which could mislead operators relying solely on voltage-monitoring systems. However, the elevated DC voltage bias and pronounced current instability clearly revealed the fault. FFT analysis confirmed the slight broadening of harmonic peaks and reinforcement of DC components but showed no substantial change in the overall harmonic structure compared to baseline conditions. This reinforces the finding that current monitoring is essential for detecting contamination-related issues that voltage magnitudes or spectra alone might not expose. From an operational perspective, a contaminated brush represents a stealthy hazard. Normal-appearing voltage signals may mask the fact that the current is flowing erratically, causing stress on the brush and shaft system. The repeated current spikes can accelerate brush wear through arcing, elevate bearing temperatures due to localized heating, and increase the likelihood of current bypassing through unintended paths. Over time, these effects can lead to damage similar to that caused by floating or loose brushes, such as pitting and electrostatic buildup. After cleaning the contaminated brush, both the current waveform and DC bias returned to stable levels, confirming the diagnosis. Brush contamination resulted in only minor increases in the RMS shaft voltage but a substantial rise in the DC offset and unstable shaft current frequency spikes with peak current values more than six times the baseline. This underscores the importance of simultaneous shaft voltage and current monitoring, as current signatures provide the decisive evidence for contamination-related faults that might otherwise escape early detection.

4. Conclusions

This work has demonstrated that online shaft voltage and current monitoring is a powerful diagnostic tool for detecting and classifying earthing-brush faults in large turbine generators.

The proposed thresholds for RMS reduction (>30–40%) and DC offset elevation (>0.1–0.2 V) are derived from empirical observation across four operational case studies rather than from a formal statistical population analysis. Healthy machines consistently exhibited stable RMS values (typically varying only ±5–10%) and negligible DC offset (<0.05 V), whereas all documented fault conditions produced substantially larger deviations. Floating-brush and worn-brush faults resulted in RMS reductions exceeding 30–40%, while floating-current-brush and contamination faults introduced DC offsets above 0.1–0.2 V. These thresholds therefore reflect robust, repeatable field signatures that align with the underlying physical mechanisms of intermittent conduction, asymmetric discharge, and semi-conductive film rectification.

The diagnostic thresholds proposed in this work were found to be consistent across both brushless and static-excited units, as well as across a range of generator sizes (246–713 MW). Although the absolute shaft voltage or shaft current magnitudes vary between machines due to differences in their excitation architectures, rotor geometries, and grounding-brush designs, the relative indicators of fault conditions were remarkably stable. All units exhibited RMS reductions greater than 30–40% during floating- or worn-brush faults, as well as DC offset elevations above 0.1–0.2 V during grounding-path discontinuities or contamination. This suggests that the underlying physical mechanisms—intermittent contact, capacitive coupling, and rectification across degraded interfaces—govern fault signatures in a manner that is largely independent of generator size or excitation technology, making the proposed thresholds broadly applicable across the fleet.

Across the four operational case studies, the diagnostic indicators proposed in this work consistently distinguished healthy grounding behavior from confirmed fault conditions. All floating-brush, worn-brush, and contamination faults manifested at least one of the characteristic signatures, RMS reductions, elevated DC offset, harmonic distortion, or impulsive peaks, without producing contradictory patterns. No false positives were noted during normal operation. Ambiguity arose only in transitional or early-stage conditions (e.g., slight brush wear or mild contamination), where deviations were detectable but below the proposed thresholds. These cases represent early-warning states rather than diagnostic failures. Overall, the field results demonstrate high reliability and the clear separability of fault signatures across units of different ratings and excitation technologies.

Although the present study did not quantify material waste in kilograms, the operational outcomes across the four units indicate meaningful waste reduction when shaft-earthing faults are detected early. Floating- and worn-brush conditions typically accelerate carbon-brush consumption and generate excess carbon dust, while undetected grounding faults can lead to bearing pitting that may require several kilograms of bearing-metal replacement and disposal of contaminated lubricant. In all the documented case studies, early detection via online monitoring enabled corrective maintenance before severe degradation occurred, preventing premature brush replacements and avoiding bearing repairs altogether. These observations suggest that effective early detection not only improves electrical and mechanical reliability but also reduces material waste streams associated with brushes, bearings, and lubricants, contributing positively to sustainability and resource efficiency.

Through a series of case studies on utility-scale generators, we systematically analyzed the electrical behavior of the shaft-grounding system under both healthy and faulted conditions, specifically examining floating brushes (voltage and current), severely worn brushes, and brushes contaminated with oil/dust. Each fault case was found to imprint a distinct signature on the shaft electrical signals, and these are summarized as follows:

A floating voltage brush leads to a near-total loss of the measured shaft voltage (a very low RMS) combined with sporadic high-voltage spikes and a surge in the shaft-grounding current through unintended paths. This condition indicates a high risk of uncontrolled discharges and bearing EDM damage.

A floating current brush causes the shaft voltage to acquire a significant DC offset and waveform distortion (with strong, even harmonics), while the intended grounding current drops to zero. The system is effectively ungrounded, severely compromising protection and greatly increasing the likelihood of bearing damage from circulating currents.

A worn brush produces extremely unstable conduction characterized by truncated or noisy voltage waveforms, a mix of odd/even harmonic content with elevated DC components, and erratic high-amplitude current spikes. This reflects intermittent contact and micro-arcing, stressing the system and potentially triggering faults if not addressed.

Oil/dust contamination on a brush has minimal effect on the nominal shaft voltage magnitude but introduces a large DC bias and frequent current surges. The voltage may appear normal to a casual glance, but the current instability reveals a hidden problem that can accelerate wear and heating.

Importantly, the investigations confirmed that even early-stage deterioration (such as minor brush contamination or partial wear) causes detectable anomalies in the electrical signatures well before catastrophic failure. In all cases, the shift from baseline behavior was clear: our high-resolution monitoring platform could identify changes in RMS values, harmonic spectra, and transient characteristics that correlate to specific faults. This provides plant engineers with actionable information not just to detect a problem but to infer which type of fault is occurring, enabling quicker and more targeted maintenance responses. The contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

It provides empirical evidence that shaft voltage and current analyses offer a reliable and sensitive method for the early detection of shaft-earthing-brush faults. The combination of time-domain indicators (waveform shape, spikes, DC drift) and frequency-domain features (harmonic patterns) significantly improves diagnostic accuracy compared to using simple thresholds.

It establishes a baseline understanding of “normal” versus “fault” signatures across different generator configurations. For instance, the persistence of the 150 Hz harmonic in healthy conditions and its behavior under faults can be used as a baseline marker.

It underscores the importance of monitoring both the shaft voltage and shaft current. Neither alone is sufficient for all fault types. Voltage monitoring excels at catching floating-voltage-brush issues, whereas current monitoring is crucial for spotting grounding disconnections and subtle problems like contamination. Together, they enable comprehensive condition assessment.

We found that a drop in the shaft voltage RMS by more than ~30–40% from its healthy baseline reliably indicated a brush contact problem (a worn or intermittently contacting brush). The appearance of a DC offset exceeding ~0.1–0.2 V was associated with floating- or contaminated-brush conditions, reflecting loss of symmetric grounding. Likewise, increases in the shaft current peaks by >100% (doubling) were observed in several fault scenarios (especially worn or contaminated brushes), and an increase of >30–40% in the shaft current RMS average pointed to significantly degraded brush contact. Conversely, a drastic decrease in current (e.g., >90% drop in RMS current through the normal path) served as a clear indicator of a completely open grounding path (as in the floating-current-brush case). These quantitative thresholds provide a starting point for setting alarm criteria in monitoring systems, although they should be calibrated to specific machine baselines.

The outcomes of this research are aligned with sustainable infrastructure management in the energy sector. Specifically, the proposed monitoring and diagnostic approach have key sustainability contributions, which include the following:

An extended generator lifespan through early intervention, thereby reducing bearing replacements, shaft refurbishments, and related waste.

Improved energy efficiency, as healthy grounding minimizes resistive losses and ensures an optimal electro-mechanical performance.

Lower environmental and operational risk by minimizing unplanned outages, emergency maintenance, and spare-part usage.

Smarter resource use by transitioning from reactive to predictive maintenance, enables leaner workforce deployment, optimized spare-part logistics, and reduced energy loss during faults.

Resilient energy systems by improving the reliability of large-scale rotating equipment that underpins grid stability.

Looking ahead, we recommend developing automated fault classification algorithms, potentially integrating machine learning to enable real-time fault detection without human interpretation. Embedding these systems within existing plant-wide monitoring frameworks will support holistic and sustainable asset management. Although the current study focused on steady-state conditions, future work should investigate fault signal behavior during transients, such as start-up, shutdown, and load changes, to enhance diagnostic robustness across full operational cycles. In conclusion, this paper establishes that the condition monitoring of shaft-grounding systems using electrical signatures is not only technically feasible but also integral to the sustainability of modern power generation systems. By enabling early fault detection, reducing downtime, minimizing environmental waste, and supporting efficient resource use, this method aligns directly with the objectives of sustainable engineering and infrastructure resilience.

A simple lumped RC charging model further explains the observed intermittent behavior, showing how weak or unstable brush contact causes the shaft to accumulate charge over a long time constant and then discharge rapidly through short, low-resistance intervals, producing the characteristic high-dV/dt spikes documented in this study.

While individual metrics such as the DC offset ratio, RMS shaft voltage ratio, or peak voltage ratio may not uniquely distinguish all fault types across different generator units, the diagnostic approach relies on the combined pattern of multiple electrical indicators rather than any single scalar parameter. Each fault mode examined in this study imprints a distinct multi-dimensional signature consisting of changes in the DC bias, RMS magnitude, peak voltage, harmonic behavior, waveform stability, and grounding-current surges. Although some individual ratios (e.g., DC offset for worn brush vs. contamination) may appear numerically close, the full parameter set clearly differentiates the faults. This confirms that shaft voltage and shaft current monitoring is most effective when interpreted holistically, using unit-specific baselines and multi-parameter deviations rather than universal thresholds.