Ecological Awareness and Behavioral Intentions Toward Sustainable Building Materials in Poland: Evidence from a Multi-Wave Nationwide Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Sampling

2.2. Variables and Measures

- Environmental Awareness—items capturing a sense of responsibility for environmental protection and the perceived importance of ecological building materials (e.g., “Using ecological materials in construction is important for protecting the climate”).

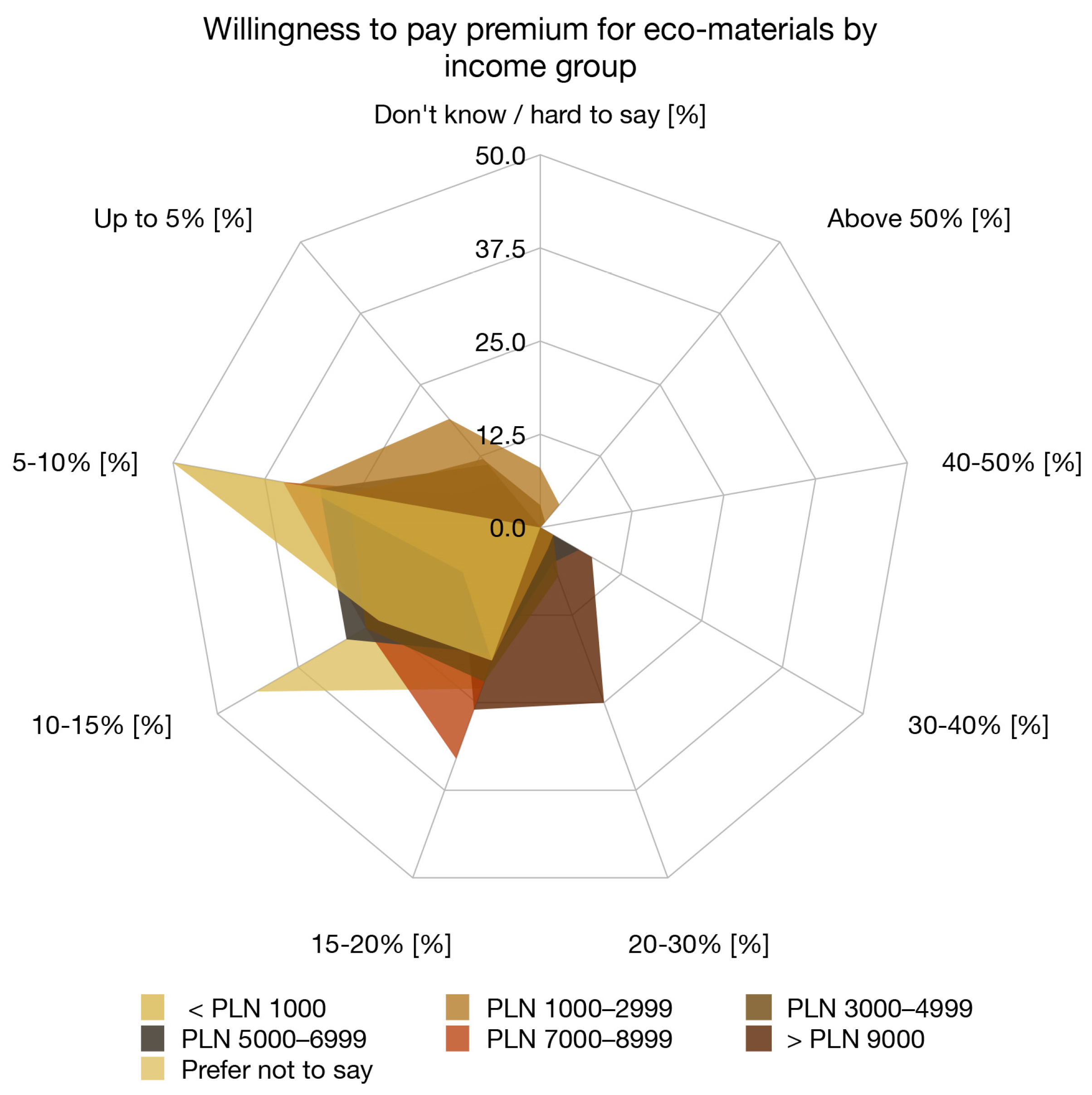

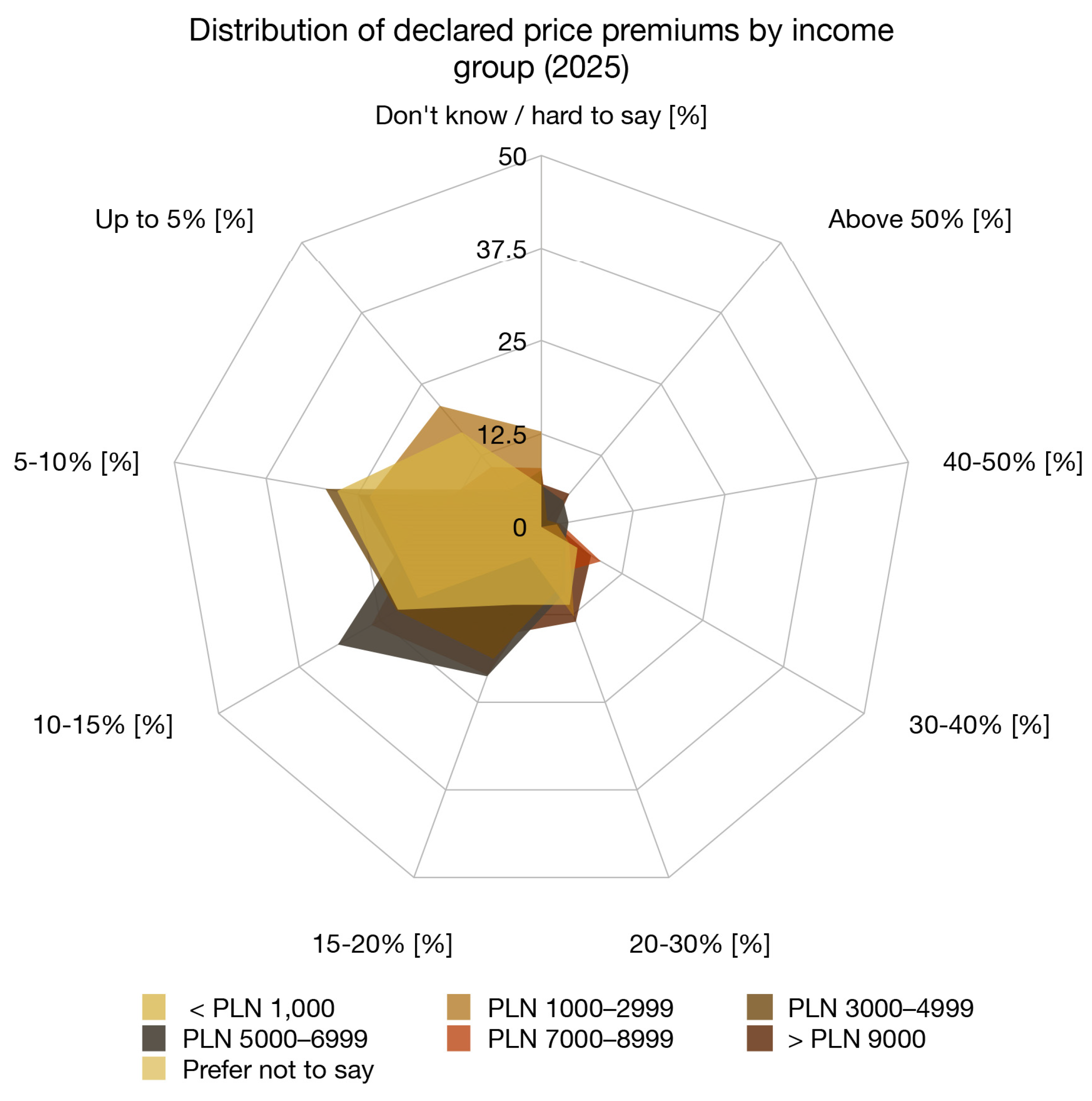

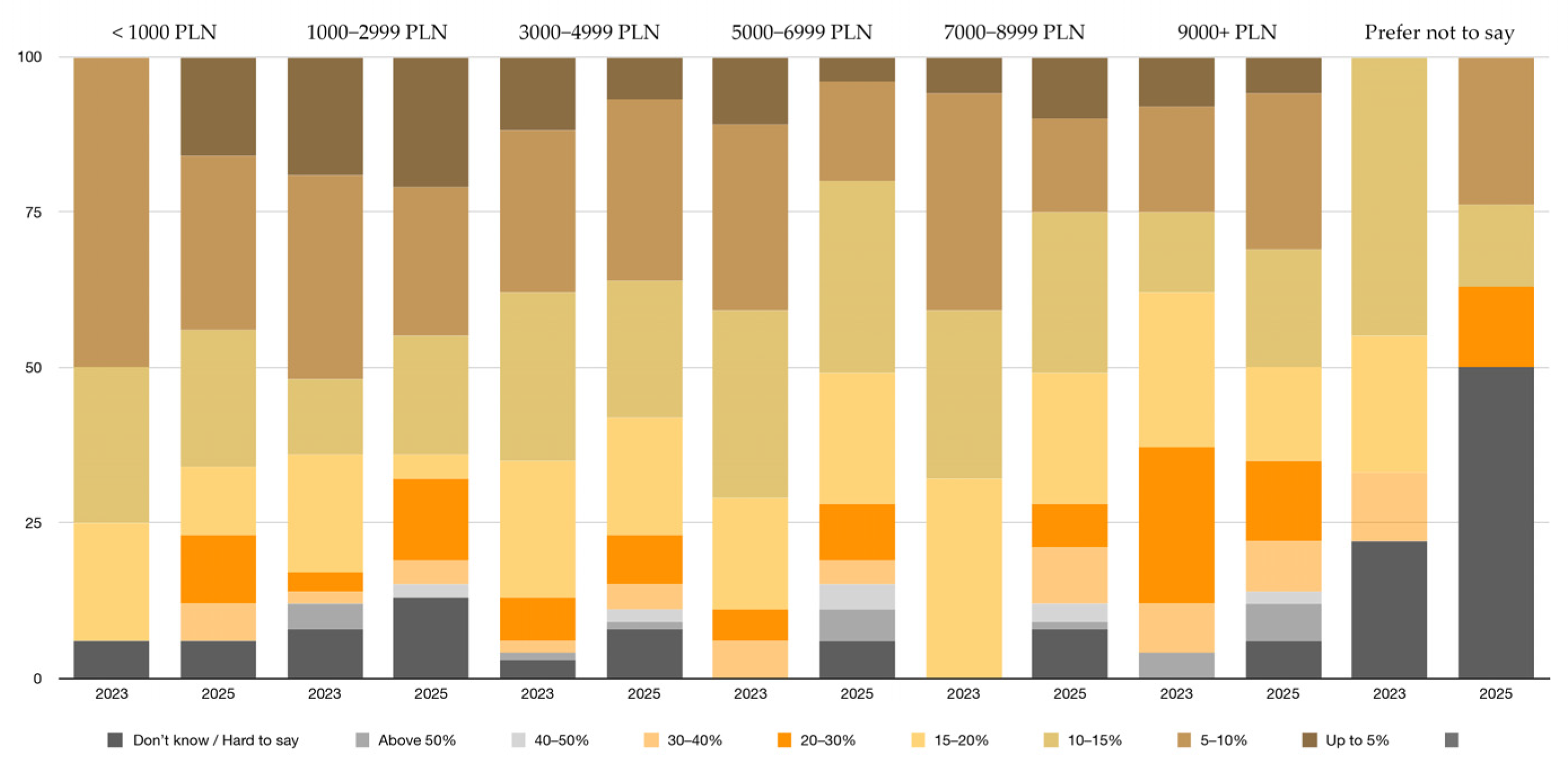

- Attitudes and Intentions—questions about willingness to choose eco-materials and willingness to pay more for properties built with such materials. In Waves 1 and 4, respondents were asked: “If you were to buy a house or apartment in the near future, would you be willing to pay more for a building constructed using environmentally friendly materials, including recycled materials?” Response options formed an ordered single-choice scale: “definitely yes”, “rather yes”, “rather no”, “definitely no”, “I don’t know/hard to say”, and, in Wave 4, an additional category “I do not intend to buy a property”. For respondents who answered positively, a follow-up question measured the price premium they were willing to pay: “How much more (above the standard price) would you be willing to spend?” The answers were given in percent We have removed commas from all four-digit numbers in the figures, in accordance with the journal’s formatting guidelines age bands (e.g., “up to 5%”, “5–10%”, “10–15%”, “15–20%”, “20–30%”, “30–40%”, “40–50%”, “more than 50%”, “I don’t know/hard to say”), creating an ordinal categorical variable).

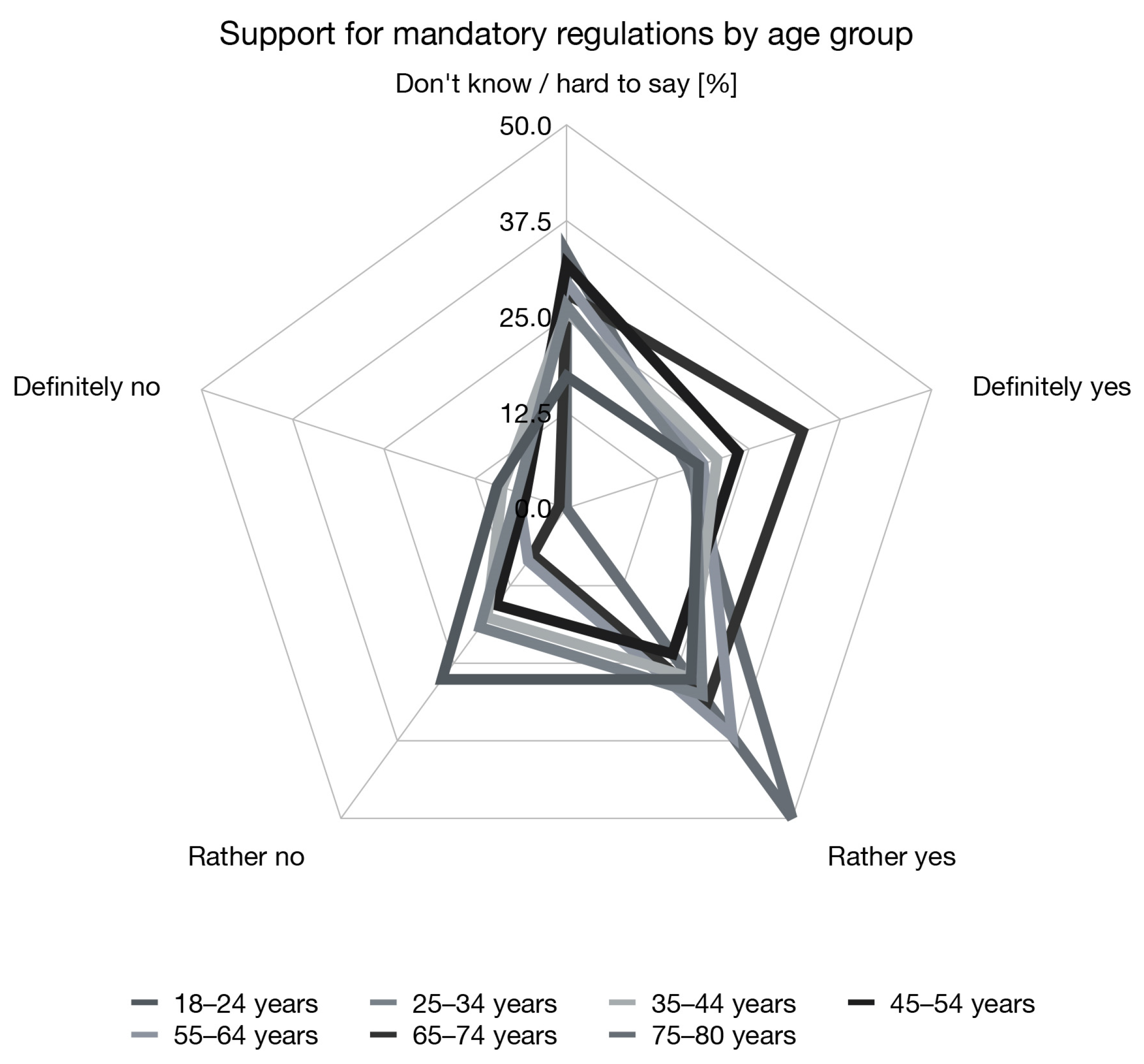

- Actual Behaviors—questions on real purchasing practices during renovation and reasons for not choosing eco-materials. In Wave 2, respondents answered whether they look for eco-friendly materials, including products made from recycled raw materials, when buying construction materials for home or apartment renovation (single-choice nominal variable with three categories: “yes, I look for them”, “no, I do not look for them”, “I do not remember/I do not pay attention”). Those who did not look for such materials were presented with a multiple-response question (“Why do you not look for such materials?”) allowing up to three reasons to be selected from a list (e.g., “they are too expensive in relation to quality”, “I do not believe that these materials are truly ecological”, “poorly labelled/not visible in stores”). Each response option was coded as a separate dichotomous variable (selected vs. not selected). In Wave 3, support for regulations obliging developers to use environmentally friendly materials was measured using an ordered single-choice scale with five options (“definitely yes”, “rather yes”, “rather no”, “definitely no”, “I don’t know/hard to say”).

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Basic Questions

3.2. Questions About Environmental Behavior

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paris Agreement Signed on 22 April 2026 The Paris Agreement|UNFCCC. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- UNEP’s Emissions Gap Report 2025: Off Target. Emissions Gap Report 2025|UNEP—UN Environment Programme. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2025 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Energy Use in Buildings in Europe. European Environment Agency Report. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/indicators/greenhouse-gas-emissions-from-energy (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- The European Green Deal. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Fit for 55: Delivering on the Proposals—European Commission. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/topics/climate-action/delivering-european-green-deal/fit-55-delivering-proposals_en (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Energy Performance of Buildings Directive. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-efficiency/energy-performance-buildings/energy-performance-buildings-directive_en (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Brock, A.; Williams, I.; Kemp, S. “I’ll take the easiest option please”. Carbon reduction preferences of the public. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 429, 139398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganglmair-Wooliscroft, A.; Wooliscroft, B. An investigation of sustainable consumption behavior systems—Exploring personal and socio-structural characteristics in different national contexts. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 148, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passer, A.; Lasvaux, S.; Allacker, K.; De Lathauwer, D.; Spirinckx, C.; Wittstock, B.; Kellenberger, D.; Gschösser, F.; Wall, J.; Wallbaum, H. Environmental product declarations entering the building sector: Critical reflections based on 5 to 10 years experience in different European countries. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2015, 20, 1199–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kylili, A.; Fokaides, P. Policy trends for the sustainability assessment of construction materials: A review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 35, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasvaux, S.; Habert, G.; Peuportier, B.; Chevalier, J. Comparison of generic and product-specific Life Cycle Assessment databases: Application to construction materials used in building LCA studies. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2015, 20, 1473–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.; Dair, C. What is stopping sustainable building in England? Barriers experienced by stakeholders in delivering sustainable developments. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 15, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häkkinen, T.; Belloni, K. Barriers and Drivers for Sustainable Building. Build. Res. Inf. 2011, 39, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darko, A.; Chan, A.P.C. Review of Barriers to Green Building. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darko, A.; Chan, A.P.C.; Owusu-Manu, D.G.; Ameyaw, E.E. Drivers for implementing green building technologies: An international survey of experts. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 145, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yang, L.; Chin, K.; Yang, Y.; Pedrycz, W.; Chang, J.-P.; Martínez, L.; Skibniewski, M.J. Sustainable building material selection: An integrated multi-criteria large group decision making framework. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 113, 107903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.; Hammad, A. A Hybrid Multi-Criteria Decision Support System for Selecting the Most Sustainable Structural Material for a Multistory Building Construction. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergel, C.; Menrad, K.; Decker, T. Which factors influence consumers’ selection of wood as building material for houses? Can. J. For. Res. 2024, 54, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, S.; Güneş, G. Determining the importance levels of criteria in selection of sustainable building materials and obstacles in their use. J. Sustain. Constr. Mater. Technol. 2024, 9, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajwa, A.; Siriwardana, C.; Shahzad, W.; Naeem, M. Material selection in the construction industry: A systematic literature review on multi-criteria decision making. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2025, 45, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudeliuniene, J.; Trinkuniene, E.; Burinskiene, A.; Bubliene, R. Application of Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Approach COPRAS for Developing Sustainable Building Practices in the European Region. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L.; Seyfang, G.; O’Neill, S. Public engagement with carbon and climate change: To what extent is the public ‘carbon capable’? Glob. Environ. Change 2011, 21, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Abdullah, A.B.; Shahir, S.A.; Kalam, M.A.; Masjuki, H.H.; Shumon, R.; Rashid, M.H. A public survey on knowledge, awareness, attitude and willingness to pay for WEEE management: Case study in Bangladesh. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 728–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoxha, E.; Jusselme, T. On the necessity of improving the environmental impacts of furniture and appliances in net-zero energy buildings. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 596–597, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weniger, A.; Del Rosario, P.; Backes, J.; Traverso, M. Consumer Behavior and Sustainability in Construction. Buildings 2023, 13, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churkina, G.; Organschi, A.; Reyer, C.P.O.; Ruff, A.; Vinke, K.; Liu, Z.; Reck, B.K.; Graedel, T.E.; Schellnhuber, H.J. Buildings as a global carbon sink. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A. Consumers’ purchase behaviour and green marketing: A synthesis, review and agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, Ł.K.; Winkler, J. Timber Construction in Poland: An Analysis of Its Contribution to Sustainable Development and Economic Growth. Drewno 2025, 68, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węgrzyn, J.; Kania, K. Heterogeneous Preferences for Sustainable Housing in Poland. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2024, 39, 749–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, J. Polish Transition towards Circular Economy: Materials Management and Implications for the Construction Sector. Materials 2020, 13, 5228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meena, C.S.; Kumar, A.; Jain, S.; Rehman, A.U.; Mishra, S.; Sharma, N.K.; Bajaj, M.; Shafiq, M.; Eldin, E.T. Innovation in Green Building Sector for Sustainable Future. Energies 2022, 15, 6631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaghefi-Rezaee, H.A.; Sarvari, H.; Khademi-Adel, S.; Roberts, C.J. A Scientometric Review and Analysis of Studies on the Barriers and Challenges of Sustainable Construction. Buildings 2024, 14, 3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikingura, A.; Grabiec, A.M.; Radomski, B. Examining Key Barriers and Relevant Promotion Strategies of Green Buildings Adoption in Tanzania. Energies 2025, 18, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Gao, X.; Xu, X.; Song, J.; Geng, Y.; Sarkis, J.; Fishman, T.; Kua, H.; Nakatani, J. A Life Cycle Thinking Framework to Mitigate the Environmental Impact of Building Materials. One Earth 2020, 3, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijekoon, R.; Sabri, M. Determinants That Influence Green Product Purchase Intention and Behavior: A Literature Review and Guiding Framework. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalejska-Jonsson, A.; Wilhelmsson, M. Impact of Perceived Indoor Environment Quality on Overall Satisfaction in Swedish Dwellings. Build. Environ. 2013, 63, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalejska-Jonsson, A. Stated WTP and rational WTP: Willingness to pay for green apartments in Sweden. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2014, 513, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, G.M.; Lakatos, E.S.; Bacali, L.; Lakatos, G.D.; Danu, B.A.; Cioca, L.-I.; Rada, E.C. Key Factors Influencing Consumer Choices in Wood-Based Recycled Products for Circular Construction Sector. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Taisch, M.; Mier, M. Influencing factors to facilitate sustainable consumption: From the experts’ viewpoints. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farjam, M.; Nikolaychuk, O.; Bravo, G. Experimental evidence of an environmental attitude-behavior gap in high-cost situations. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 166, 106434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, J.; Michałowski, B. Understanding Sustainability of Construction Products among Market Actors. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Change in Europe: Facts and Figures. Updated on 6 December 2024 Climate Change in Europe: Facts and Figures|Topics|European Parliament. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20180703STO07123/climate-change-in-europe-facts-and-figures#the-eus-biggest-greenhouse-gases-emitters-countries-and-sectors-6 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Steg, L. Psychology of climate change. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2023, 74, 391–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Wave | Implementation Period | Sample Size (N) | Target Group (Age) | Main Objective of the Wave |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 | 8–11 June 2023 | 1030 | 18–65 | WTP for eco-materials in new housing |

| Wave 2 | 24–26 June 2023 | 1008 | 18–80 | Search behavior and barriers in DIY/building stores |

| Wave 3 | 28–29 September 2023 | 1026 | 18–80 | Support for regulations obliging developers to use eco-materials |

| Wave 4 | 21–23 September 2025 | 1003 | 18–80 | Post-EPBD and KPO: updated WTP and behavioral changes |

| Answer | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| Don’t know/Hard to say | 19.2 | 23.6 |

| Definitely yes | 12.0 | 11.5 |

| Rather yes | 22.3 | 23.8 |

| Rather no | 22.1 | 18.5 |

| Definitely no | 14.9 | 13.2 |

| I don’t intend to buy anything | 23.6 | 9.3 |

| Answer | <PLN 1000 | PLN 1000–2999 | PLN 3000–4999 | PLN 5000–6999 | PLN 7000–8999 | >PLN 9000 | Prefer Not to Say |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Don’t know/ Hard to say | 6.3% | 8.2% | 2,9% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 22.2% |

| Above 50% | 0% | 4.1% | 0.7% | 0% | 0% | 4.2% | 0% |

| 40–50% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 30–40% | 0% | 1.4% | 1.5% | 6.3% | 0% | 8.3% | 11.2% |

| 20–30% | 0% | 2.7% | 7.3% | 4.8% | 0% | 25.0% | 0% |

| 15–20% | 18.7% | 19.2% | 21.9% | 17.5% | 32.4% | 25.0% | 22.2% |

| 10–15% | 25.0% | 12.3% | 27.0% | 30.2% | 27.0% | 12.5% | 44.2% |

| 5–10% | 50.0% | 32.9% | 26.3% | 30.2% | 35.1% | 16.7% | 0% |

| Up to 5% | 0% | 19.2% | 12.4% | 11.0% | 5.5% | 8.3% | 0% |

| Answer | [%] |

|---|---|

| Don’t know/Hard to say | 24.3 |

| Definitely yes | 6.8 |

| Rather yes | 9.1 |

| Rather no | 33.7 |

| Definitely no | 26.1 |

| Answer | 18–24 Years | 25–34 Years | 35–44 Years | 45–54 Years | 55–64 Years | 65–74 Years | 75–80 Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Don’t know/Hard to say | 17.2% | 26.4% | 25.7% | 31.8% | 29.5% | 28.0% | 33.3% |

| Definitely yes | 18.1% | 17.6% | 20.6% | 23.5% | 18.7% | 32.3% | 16.7% |

| Rather yes | 27.6% | 30.1% | 27.3% | 23.5% | 36.7% | 31.2% | 50.0% |

| Rather no | 27.6% | 19.2% | 17.6% | 15.6% | 8.5% | 7.5% | 0.0% |

| Definitely no | 9.5% | 6.7% | 8.8% | 5.6% | 6.6% | 1.0% | 0.0% |

| Answer | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| Don’t know/Hard to say | 20.2% | 25.6% |

| Definitely yes | 19.8% | 16.5% |

| Rather yes | 28.9% | 30.3% |

| Rather no | 15.9% | 17.0% |

| Definitely no | 8.7% | 4.6% |

| I don’t intend to buy anything | 6.5% | 6.0% |

| Answer | <PLN 1000 | PLN 1000–2999 | PLN 3000–4999 | PLN 5000–6999 | PLN 7000–8999 | >PLN 9000 | Prefer Not to Say |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Don’t know/ Hard to say | 5.6% | 12.8% | 7.6% | 5.6% | 7.9% | 5.8% | 50.0% |

| Above 50% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.2% | 4.6% | 1.3% | 5.8% | 0% |

| 40–50% | 0.0% | 2.1% | 2.4% | 3.7% | 2.6% | 1.9% | 0% |

| 30–40% | 5.6% | 4.3% | 3.5% | 3.7% | 9.2% | 7.7% | 0% |

| 20–30% | 11.1% | 12.8% | 8.2% | 9.3% | 6.6% | 13.5% | 12.5% |

| 15–20% | 11.1% | 4.3% | 18.8% | 21.3% | 21.1% | 15.4% | 0% |

| 10–15% | 22.2% | 19.1% | 22.4% | 31.5% | 26.3% | 19.1% | 12.5% |

| 5–10% | 27.8% | 23.4% | 29.4% | 15.7% | 14.5% | 25.0% | 25% |

| Up to 5% | 16.6% | 21.1% | 6.5% | 4.6% | 10.5% | 5.8% | 0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dendura, B.; Porębska, A. Ecological Awareness and Behavioral Intentions Toward Sustainable Building Materials in Poland: Evidence from a Multi-Wave Nationwide Survey. Sustainability 2026, 18, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010102

Dendura B, Porębska A. Ecological Awareness and Behavioral Intentions Toward Sustainable Building Materials in Poland: Evidence from a Multi-Wave Nationwide Survey. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010102

Chicago/Turabian StyleDendura, Bartosz, and Anna Porębska. 2026. "Ecological Awareness and Behavioral Intentions Toward Sustainable Building Materials in Poland: Evidence from a Multi-Wave Nationwide Survey" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010102

APA StyleDendura, B., & Porębska, A. (2026). Ecological Awareness and Behavioral Intentions Toward Sustainable Building Materials in Poland: Evidence from a Multi-Wave Nationwide Survey. Sustainability, 18(1), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010102