Optimizing Tour Guide Selection: A Best–Worst Scaled Assessment of Critical Performance Criteria for Enhanced Tour Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Relevant Literature

2.1. Tour Guide Evaluation Research and Criteria Selection

2.2. Role and Impact of Tour Guides in Tourism Experience

2.3. Evaluation Criteria for Tour Guide Performance: Comparative Analysis of Previous Studies

2.4. Application of MCDM Methodologies in Tourism and Tour Guide Evaluation

3. Methodology

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Local Cultural and Historical Background

4.2. Language Proficiency Skills

4.3. Time Management and Punctuality Assessment

4.4. Environmental and Ethical Awareness

4.5. Emergency Response Time

4.6. Practical Experience

4.7. Customer Service Skills

4.8. Technology Adaption Score

4.9. Safety and First Aid Training Score

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Castro, J.C.; Quisimalin, M.; de Pablos, C.; Gancino, V.; Jerez, J. Tourism marketing: Measuring tourist satisfaction. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2017, 10, 280–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, D.M.N.D. The quest for adventure: A Tourist’s perspective on choosing attractions in Zambales, Philippines. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2023, 17, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, I. The Role of the Tour Guide in Transferring Cultural Understanding. Sch. Leis. Sport Tour. 2001, 3, 1836–9979. Available online: https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/bitstream/2100/893/1/lstwp3.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Alqahtani, A.Y.; Makki, A.A. A DEMATEL-ISM Integrated Modeling Approach of Influencing Factors Shaping Destination Image in the Tourism Industry. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quality of Life Program. Tourism Dashboard; Ministry of Tourism: New Delhi, India, 2025. Available online: https://mt.gov.sa/tic/dashboard/inbound-tourism (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Tsaur, S.-H.; Teng, H.-Y. Exploring tour guiding styles: The perspective of tour leader roles. Tour. Manag. 2016, 59, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Zhao, H. An Analysis on the Strategy of the Improvement of Languages Art of Tour Guides; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oroceo, M. Evaluation of Tour Guides’ Performance to the Satisfaction of Local Tourists in Intramuros, Manila. 2023. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/94074600/evaluation_of_tour_guides_performance_to_the_satisfaction_of_local_tourists_in_intramuros_manila (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Rezaei, J. Best-worst Multi-criteria Decision-making Method. Omega 2015, 53, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. The tourist guide: The origins, structure and dynamics of a role. Ann. Tour. Res. 1985, 12, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, J. The guided tour a sociological approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 1981, 8, 377–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, R.; Weiler, B. Quality assurance and regulatory mechanisms in the tour guiding industry: A systematic review. J. Tour. Stud. 2005, 16, 24–37. Available online: https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.200509017 (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Wong, J.-Y.; Wang, C.-H. Emotional labor of the tour leaders: An exploratory study. Tour. Manag. 2008, 30, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Q.; Chow, I. Application of importance-performance model in tour guides’ performance: Evidence from mainland Chinese outbound visitors in Hong Kong. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Hsu, C.H.C.; Chan, A. Tour Guide Performance and Tourist Satisfaction: A Study of the Package Tours in Shanghai. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2009, 34, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabotić, B. Tourist guides in contemporary tourism. In International Conference on Tourism and Environment; Philip Noel-Baker University: Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2010; pp. 353–364. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, K.-C. Examining the Effect of Tour Guide Performance, Tourist Trust, Tourist Satisfaction, and Flow Experience on Tourists’ Shopping Behavior. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 19, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandaruwani, J.; Gnanapala, W.A.C. The role of tourist guides and their impacts on sustainable tourism development: A critique on Sri Lanka. Tour. Leis. Glob. Change 2016, 3, 62–73. Available online: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/20173155188 (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Weiler, B.; Walker, K. Enhancing the visitor experience: Reconceptualising the tour guide’s communicative role. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2014, 21, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatori, A.; Smith, M.K.; Puczko, L. Experience-involvement, memorability and authenticity: The service provider’s effect on tourist experience. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.-W.; Xu, F.-F.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.-T. Tourists’ Attitudes Toward Tea Tourism: A Case Study in Xinyang, China. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ap, J.; Wong, K.K. Case study on tour guiding: Professionalism, issues and problems. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Actors in Cultural Tourism Practices; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rini, N.A.; Firdaus, L.A. Evaluation of Tour Guide Communication in Providing Guiding to Foreigners as Tourists. Int. J. Travel. Hosp. Events 2022, 1, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacchini, A.; Guizzardi, A.; Costa, M. The Value of Sustainable Tourism Destinations in the Eyes of Visitors. Highlights Sustain. 2022, 1, 202–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumov, K. Tourists Perceptions and Satisfaction Regarding Tour Guiding in the Republic of North Macedonia. Eur. J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2020, 5, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anom, I.P.; Mahagangga, I.G.O.; Suryawan, I.B.; Koesbardiati, T.; Wulandari, I.G.A.A. Case Study of Balinese Tourism: Myth as Cultural Capital. Utopía Y Prax. Latinoam. 2020, 25, 122–133. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/8069667.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Fennell, D.A. Tourism ethics needs more than a surface approach. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2008, 33, 223–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kafy, J.A. Challenges Facing Tour Guide Profession and their Impacts on the Egyptian Guides performance. J. Assoc. Arab. Univ. Tour. Hosp. 2021, 19, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejmeddin, A.I. The Importance of Tour Guides in Increasing the Number of Tourists at a Tourist Destination. Polytech. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2021, 1, 18–23. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348338623_The_Importance_of_Tour_Guides_in_Increasing_the_Number_of_Tourists_at_a_Tourist_Destination (accessed on 26 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Patria, T.A.; Ulinnuha, H.; Hidayah, N.; Latif, A.N.K.; Susanto, E.; Claudia, C. Effect of Key Opinion Leaders and Instagram Posts on Wonderful Indonesia Brand Awareness. EDP Sci. 2023, 426, 2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, V.; Eusébio, C.; Breda, Z. Enhancing sustainable development through tourism digitalisation: A systematic literature review. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2022, 25, 13–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotohy, H. New Trends in Tour Guiding, The Guide faces Technology ‘Applied study to selected sites in Egypt’. J. Assoc. Arab. Univ. Tour. Hosp. 2021, 19, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Deng, B. Exploring the nexus of smart technologies and sustainable ecotourism: A systematic review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uriely, N. The tourist experience: Conceptual Developments. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanwanakul, S. Effectiveness of Tour Guides’ Communication Skills at Historical Attractions. Int. J. Entrep. 2021, 25, 1–10. Available online: https://www.abacademies.org/articles/effectiveness-of-tour-guides-communication-skills-at-historical-attractions.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Orabi, R.; Fadel, D. The Role of Tour Guide Performance in Creating Responsible Tourist Behavior: An Empirical Study: Archaeological Sites in Alexandria. Int. J. Herit. Tour. Hosp. 2020, 14, 325–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şengel, Ü.; Çevrimkaya, M.; Zengin, B. The effect of professional expectations of tour guiding students on their professional motivation. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2021, 29, 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Cros, H.D. Cultural Tourism: The Partnership Between Tourism and Cultural Heritage Management; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Okaily, N.S. A Model for Tour Guide Performance. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2022, 23, 1077–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanan, A.; Sugianto, S. The communication strategies on tourist guide professionalism in lombok west nusa tenggara. J. Lang. Lang. Teach. 2021, 9, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syakier, W.A.; Hanafiah, M.H. Tour Guide Performances, Tourist Satisfaction And Behavioural Intentions: A Study On Tours In Kuala Lumpur City Centre. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 23, 597–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, H.D.; Irawati, N.; Santoso, H.T. Analisis kualitas pelayanan tour guide di destinasi wisata benteng marlborough bengkulu. Kepariwisataan J. Ilm. 2022, 16, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, S.W.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Pan, B. Electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, N.P. Foundations of Tourism; Prentice-Hall Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Muthiah, J.; Muntasib, E.K.S.H.; Meilani, R. Tourism hazard potentials in Mount Merapi: How to deal with the risk. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018; Volume 149, p. 12020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhofer, B.; Buhalis, D.; Ladkin, A. Smart technologies for personalized experiences: A case study in the hospitality domain. Electron. Mark. 2015, 25, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gültekin, S.; Icigen, E. A Research on Professional Tour Guides Emotional Intelligence and Problem-Solving Skills. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 20, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. The Analytic Hierarchy Process: Decision Making in Complex Environments. In Quantitative Assessment in Arms Control: Mathematical Modeling and Simulation in the Analysis of Arms Control Problems; Avenhaus, R., Huber, R.K., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1984; pp. 285–308. [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar, J.J. Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). In Multi-Criteria Decision Making; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan, D.; Sevim, E. Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Techniques in Medical Tourism Studies: A Systematic Review TT-Medikal Turizm Çalışmalarında Çok Kriterli Karar Verme Teknikleri: Bir Sistematik Derleme. Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi Vizyoner Derg. 2022, 13, 1305–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Deng, W.; Yuan, J. Evaluation of sports tourism competitiveness of urban agglomerations in Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forouzandeh, S.; Rostami, M.; Berahmand, K. A Hybrid Method for Recommendation Systems based on Tourism with an Evolutionary Algorithm and Topsis Model. Fuzzy Inf. Eng. 2022, 14, 26–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazhuhan, M.; Shiri, N. Regional tourism axes identification using GIS and TOPSIS model (Case study: Hormozgan Province, Iran). J. Tour. Anal. Rev. Análisis Turístico 2020, 27, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Sharma, M.; Singh, R.K. Performance Evaluation of Agro-tourism Clusters using AHP–TOPSIS. J. Oper. Strat. Plan. 2020, 3, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, K.; Ocampo, L. Utilizing TOPSIS-Sort for sorting tourist sites for perceived COVID-19 exposure. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 25, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, L.T.H.; Hien, D.T.T.; Thong, N.T.; Smarandache, F.; Giang, N.L. An ANP-TOPSIS model for tourist destination choice problems under Temporal Neutrosophic environment. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 136, 110146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawansyah, S. Sistem Pendukung Keputusan Rekomendasi Tempat Wisata Menggunakan Metode TOPSIS. J. Ilm. Inform. dan Ilmu Komput. 2022, 1, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuangpornpitak, W.; Boonchom, W.; Suphan, K.; Chiengkul, W.; Tantipanichkul, T. Application of TOPSIS-LP and New Routing Models for the Multi-Criteria Tourist Route Problem: The Case Study of Nong Khai, Thailand. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2024, 14, 14929–14938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Yang, S.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Škare, M. An overview of fuzzy multi-criteria decision-making methods in hospitality and tourism industries: Bibliometrics, methodologies, applications and future directions. Econ. Res. Istraz. 2022, 36, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Bai, C.; Shi, L.; Puška, A.; Štilić, A.; Stević, Ž. Assessment of Mountain Tourism Sustainability Using Integrated Fuzzy MCDM Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuriyev, A.M. Fuzzy MCDM models for selection of the tourism development site: The case of Azerbaijan. F1000Research 2022, 11, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shokraneh, F.; Adams, C.E. A simple formula for enumerating comparisons in trials and network meta-analysis. F1000Research 2019, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saaty, T.L.; Ergu, D. When is a decision-making method trustworthy? Criteria for evaluating multi-criteria decision-making methods. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Decis. Mak. 2015, 14, 1171–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulaal, R.M.S.; Bafail, O.A. BWM—RAPS Approach for Evaluating and Ranking Banking Sector Companies Based on Their Financial Indicators in the Saudi Stock Market. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulaal, R.M.S.; Bafail, O.A. A Comparative Study between GLP and GBWM. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 5555933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, M.; Bafail, O.; Alidrisi, H. HVAC Systems Evaluation and Selection for Sustainable Office Buildings: An Integrated MCDM Approach. Buildings 2023, 13, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsanousi, A.T.; Alqahtani, A.Y.; Makki, A.A.; Baghdadi, M.A. A Hybrid MCDM Approach Using the BWM and the TOPSIS for a Financial Performance-Based Evaluation of Saudi Stocks. Information 2024, 15, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barasin, A.M.; Alqahtani, A.Y.; Makki, A.A. Performance Evaluation of Retail Warehouses: A Combined MCDM Approach Using G-BWM and RATMI. Logistics 2024, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamučar, D.; Ecer, F.; Cirovic, G.; Arlasheedi, M.A. Application of Improved Best Worst Method (BWM) in Real-World Problems. Mathematics 2020, 8, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J.; Nispeling, T.; Sarkis, J.; Tavasszy, L. A supplier selection life cycle approach integrating traditional and environmental criteria using the best worst method. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krstić, M.; Tadić, S.; Miglietta, P.P.; Porrini, D. Biodiversity Protection Practices in Supply Chain Management: A Novel Hybrid Grey Best–Worst Method/Axial Distance-Based Aggregated Measurement Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Model. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Kaushik, M.K.; Kumar, R.; Khan, W. Investigating the barriers of blockchain technology integrated food supply chain: A BWM approach. Benchmarking Int. J. 2022, 30, 713–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Khan, S.; Haleem, A. Analysing barriers towards management of Halal supply chain: A BWM approach. J. Islam. Mark. 2019, 13, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badri Ahmadi, H.; Kusi-Sarpong, S.; Rezaei, J. Assessing the social sustainability of supply chains using Best Worst Method. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 126, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaswan, M.S.; Rathi, R. Investigation of life cycle assessment barriers for sustainable development in manufacturing using grey relational analysis and best worst method. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2021, 14, 672–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, J.; Moslem, S.; Tóth, J.; Péter, T.; Palaguachi, J.; Paguay, M. Using Best Worst Method for Sustainable Park and Ride Facility Location. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, N.; Rezaei, J. Evaluating firms’ R&D performance using best worst method. Eval. Program Plan. 2018, 66, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M.W.; Pumpin, M.d.L.Á.R.; Vargas, G. Prioritization of Water Footprint Management Practices and Their Effect on Agri-Food Firms’ Reputation and Legitimacy: A Best–Worst Method Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikis, J.; Bathaei, A.; Štreimikienė, D. Sustainability assessment of the agriculture sector using best worst method: Case study of Baltic states. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 5611–5626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi-Babadi, A.; Bozorgi-Amiri, A.; Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, R. Sustainable facility relocation in agriculture systems using the GIS and best–worst method. Kybernetes 2021, 51, 2343–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, C.; Micheels, E.T. Identifying risk in production agriculture: An application of best-worst scaling. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2020, 23, 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everest, T.; Sungur, A.; Özcan, H. Applying the best–worst method for land evaluation: A case study for paddy cultivation in northwest Turkey. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 19, 3233–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyüz, G.; Yalpir, Ş.; Ertunç, E. Determining the Suitability of Lands for Agricultural Use with the Best-Worst Method. Afyon Kocatepe Univ. J. Sci. Eng. 2023, 23, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samani, Z.N.; Alesheikh, A.A.; Karimi, M.; Samany, N.N.; Bayat, S.; Lotfata, A.; Garau, C. Advancing Urban Healthcare Equity Analysis: Integrating Public Participation GIS with Fuzzy Best–Worst Decision-Making. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslem, S.; Campisi, T.; Szmelter-Jarosz, A.; Duleba, S.; Nahiduzzaman, K.M.; Tesoriere, G. Best–Worst Method for Modelling Mobility Choice after COVID-19: Evidence from Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boz, E.; Çizmecioğlu, S.; Çalık, A. A Novel MDCM Approach for Sustainable Supplier Selection in Healthcare System in the Era of Logistics 4.0. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslem, S.; Gul, M.; Farooq, D.; Celik, E.; Ghorbanzadeh, O.; Blaschke, T. An Integrated Approach of Best-Worst Method (BWM) and Triangular Fuzzy Sets for Evaluating Driver Behavior Factors Related to Road Safety. Mathematics 2020, 8, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrudi, S.H.H.; Ghomi, H.; Mazaheriasad, M. An Integrated Fuzzy Delphi and Best Worst Method (BWM) for performance measurement in higher education. Decis. Anal. J. 2022, 4, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour, M.J.; Mesrabadi, J.; Hosseinzadeh, M. A comprehensive framework to rank cloud-based e-learning providers using best-worst method (BWM). Online Inf. Rev. 2019, 44, 114–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour, M.J.; Hosseinzadeh, M.; Rafiei, K. Identifying and prioritizing applications of Internet of Things (IOT) in educational learning using Interval Best-Worst Method (BWM). In Proceedings of the 2020 4th International Conference on Smart City, Internet of Things and Applications (SCIOT), Mashhad, Iran, 16–17 September 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorani, S.F.; Serkani, M.; Karimi, Z. Identifying and prioritizing the applications of game theory in the educational and learning environments using the BWM. Technol. Educ. J. 2023, 17, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, R.; Guzman, A.F. A perspective on emerging energy policy and economic research agenda for enabling aviation climate action. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 117, 103725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, P.E.; Beggs, J.R.; Binny, R.N.; Bray, J.P.; Cogger, N.; Dhami, M.K.; French, N.P.; Grant, A.; Hewitt, C.L.; Jones, E.E.; et al. “Emerging advances in biosecurity to underpin human, animal, plant, and ecosystem health. Iscience 2023, 26, 107462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robison, R.; Skjølsvold, T.M.; Hargreaves, T.; Renström, S.; Wolsink, M.; Judson, E.; Pechancová, V.; Demirbağ-Kaplan, M.; March, H.; Lehne, J.; et al. Shifts in the smart research agenda? 100 priority questions to accelerate sustainable energy futures. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 419, 137946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleser, M.; Elbert, R. Combined rail-road transport in Europe–A practice-oriented research agenda. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2024, 53, 101101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reefke, H.; Sundaram, D. Key themes and research opportunities in sustainable supply chain management–identification and evaluation. Omega 2017, 66, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, R.; Almutairi, S.; Bansal, P. Emerging energy economics and policy research priorities for enabling the electric vehicle sector. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 1836–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Kannan, D.; Jørgensen, T.B.; Nielsen, T.S. Supply Chain 4.0 performance measurement: A systematic literature review, framework development, and empirical evidence. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 164, 102725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Verbal Judgment | Numeric Value |

|---|---|

| Absolutely more important | 9 |

| Somewhat between very strong and absolute | 8 |

| Very strongly more important | 7 |

| Somewhat between strong and very strong | 6 |

| Strongly more important | 5 |

| Somewhat between moderate and strong | 4 |

| Moderately more important | 3 |

| Somewhat between equal and moderate | 2 |

| Equally important | 1 |

| Code | Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| C1 | Local Cultural and Historical Background | Maximization |

| C2 | Language Proficiency Skills | Maximization |

| C3 | Time Management and Punctuality Assessment | Minimization |

| C4 | Environmental and Ethical Awareness | Maximization |

| C5 | Emergency Response Time | Minimization |

| C6 | Practical Experience | Maximization |

| C7 | Customer Service Skills | Maximization |

| C8 | Technology Adaption Score | Maximization |

| C9 | Safety and First Aid Training Score | Maximization |

| Expert | Qualification | Field | Years of Experience in Tourism |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | B.Sc. | Human Resources | 4 |

| E2 | Higher Diploma | Hospitality | >1 |

| E3 | M.Sc. | Hospitality | 10 |

| E4 | B.Sc. | Hospitality | >2 |

| E5 | B.Sc. | Education | <2 |

| E6 | Higher Diploma | Hospitality | 30 |

| E7 | Higher Diploma | Hospitality | >1 |

| E8 | Higher Diploma | Customer Service | 1 |

| E9 | M.Sc. | Human Resources | 1 |

| E10 | B.Sc. | Healthcare | >1 |

| E11 | B.Sc. | Industry | >2 |

| E12 | Ph.D. | Education | 3 |

| Best-to-Others | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Criteria | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | C7 | C8 | C9 |

| C1 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Others-to-Worst | |

|---|---|

| Main Criteria | C8 |

| C1 | 5 |

| C2 | 6 |

| C3 | 5 |

| C4 | 6 |

| C5 | 5 |

| C6 | 7 |

| C7 | 5 |

| C8 | 1 |

| C9 | 5 |

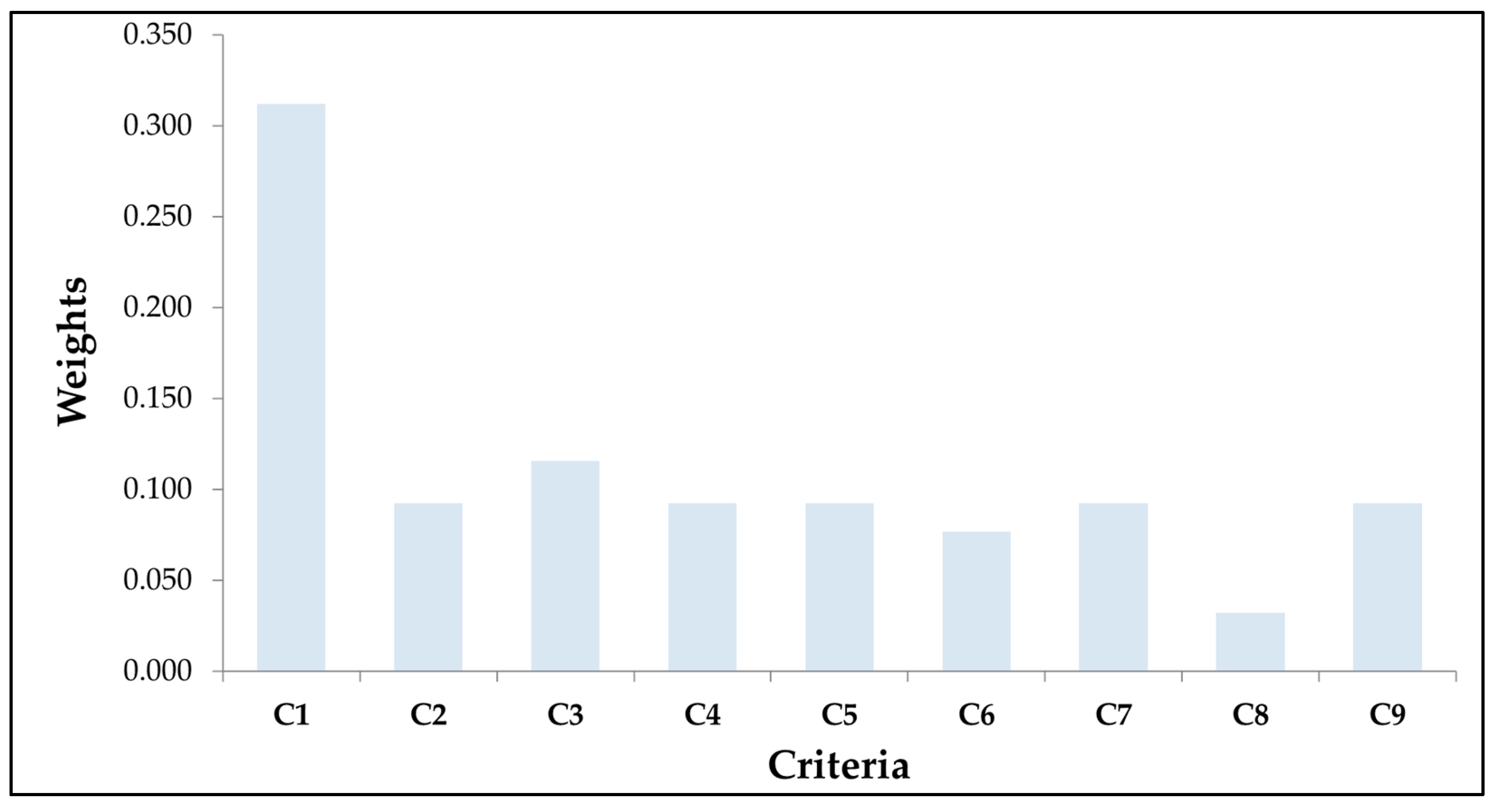

| Criteria | Weight |

|---|---|

| C1—Local Cultural and Historical Background | 0.312 |

| C2—Language Proficiency Skills | 0.092 |

| C3—Time Management and Punctuality Assessment | 0.116 |

| C4—Environmental and Ethical Awareness | 0.092 |

| C5—Emergency Response Time | 0.092 |

| C6—Practical Experience | 0.077 |

| C7—Customer Service Skills | 0.092 |

| C8—Technology Adaption Score | 0.032 |

| C9—Safety and First Aid Training Score | 0.092 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bafail, O.; Hanbazazah, A. Optimizing Tour Guide Selection: A Best–Worst Scaled Assessment of Critical Performance Criteria for Enhanced Tour Quality. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4213. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094213

Bafail O, Hanbazazah A. Optimizing Tour Guide Selection: A Best–Worst Scaled Assessment of Critical Performance Criteria for Enhanced Tour Quality. Sustainability. 2025; 17(9):4213. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094213

Chicago/Turabian StyleBafail, Omer, and Abdulkader Hanbazazah. 2025. "Optimizing Tour Guide Selection: A Best–Worst Scaled Assessment of Critical Performance Criteria for Enhanced Tour Quality" Sustainability 17, no. 9: 4213. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094213

APA StyleBafail, O., & Hanbazazah, A. (2025). Optimizing Tour Guide Selection: A Best–Worst Scaled Assessment of Critical Performance Criteria for Enhanced Tour Quality. Sustainability, 17(9), 4213. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094213

_Li.png)