Abstract

Building on our prior research with a national survey sample of 5385 US participants, the Pooled Rideshare Acceptance Model (PRAM) was built upon two factor analyses. This exploratory study extends the PRAM framework using the Pooled Rideshare Acceptance Model Multigroup Analyses (PRAMMA) to examine how 16 demographic variables influence and interact with the acceptance of Pooled Rideshare (PR), filling a gap in understanding user segmentation and personalization. Using a national sample of 5385 US participants, this methodological approach allowed for the evaluation of how PRAM variables such as safety, privacy, service experience, and environmental impact vary across diverse groups, including gender, generation, driver’s license, rideshare experience, education level, employment status, household size, number of children, income, vehicle ownership, and typical commuting practices. Factors such as convenience, comfort, and passenger safety did not show significant differences across the moderators, suggesting their universal importance across all demographics. Furthermore, geographical differences did not significantly impact the relationships within the model, suggesting consistent relationships across different regions. The findings highlight the need to move beyond a “one size fits all” approach, demonstrating that tailored strategies may be crucial for enhancing the adoption and satisfaction of PR services among various demographic groups. The analyses provide valuable insight for policymakers and rideshare companies looking to optimize their services and increase user engagement in PR.

1. Introduction

1.1. Rideshare Services

Personal rideshare services like Uber and Lyft in the US have reshaped transportation over the last decade, enabling passengers to book rides using mobile apps efficiently. Personal rideshare services allow individuals to travel alone or with known companions. These companies have become an integral part of the transportation ecosystem, offering a flexible and convenient alternative to traditional car ownership and public transit. Services offered by companies such as Uber and Lyft cater to passengers seeking privacy, convenience, and direct routes to their destinations. By 2017, Uber alone had expanded to 224 urban areas across the United States [1]. Such expansion highlights the substantial role Transportation Network Companies (TNCs) play, especially in densely populated cities. For instance, by 2016, TNCs accounted for 15% of all intra-city vehicle trips on average weekdays in San Francisco [2]. In 2017, Uber and Lyft transported 2.61 billion passengers—a 37% increase from the 1.90 billion passengers in 2016, indicating a rapid adoption rate among users [3]. A significant portion of these rides occurred in major metropolitan areas like Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, Miami, New York City, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington D.C., where they have become essential components of the local transport networks. This expansion reflects a broader trend of increasing reliance on TNCs, which contrasts with the declining use of traditional taxi services and carpooling, which steadily decreased from 19.7% in 1980 to 9.4% in 2013 [4]. Such trends demonstrate the growing preference for on-demand, personalized transportation solutions offered by TNCs, reshaping how people commute and travel within urban environments [5].

1.2. Emergence of Pooled Rideshare

Along with personal rideshare, in recent years, pooled rideshare (PR) has emerged as another significant evolution within mobility, offering even more alternatives to traditional transportation modes [6]. Pooled rideshare, where travelers share a vehicle with others they do not know and who may enter or exit the trip at different locations, has been popularized by major TNCs, including Uber and Lyft, through services such as UberPool or UberX Share and LyftLine or Lyft Shared [7,8]. According to Schaller [3], by 2018, 20% of all Uber trips were made via sharing the ride, demonstrating its substantial adoption. Moreover, Carrier et al. [9] suggest that despite the added travel time due to multiple passenger pickups, this model offers cost advantages that are attractive to riders, although it introduces complexities such as increased travel time and different safety concerns due to sharing a ride with strangers than personal rideshare.

The integration of advanced technology once again plays a pivotal role in facilitating the efficient operation of pooled rideshare services. These platforms utilize even more complicated dynamic ride-matching algorithms supported by real-time data to optimize routes and increase service capabilities. As noted by Levosky and Greenberg [10] and Siddiqi and Buliung [11], such technological advancements are critical in addressing the logistical challenges inherent in coordinating multiple pickups and drop-offs. Furthermore, the societal and environmental benefits of reduced traffic congestion and pollution, as highlighted by Moody et al. [12], align with broader sustainability goals, making pooled rideshare an increasingly attractive option for travelers and the environment. Yet, challenges remain with rider buy-in, particularly in convincing potential users of the safety and reliability of sharing rides with unknown riders, as shown by the hesitation of riders observed in various studies [13,14].

In 2014, Uber introduced its PR service, UberPool, and in the same year, Lyft launched its equivalent service, LyftLine [15]. The utilization of PR services was focused in large, densely populated urban areas. The service initially started by experimenting in San Francisco and, by 2017, spread across nine major metropolitan areas—Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, Miami, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington D.C.—these cities comprise 23% of the total US population [3]. As of 2024, PR availability extended to 27 metropolitan areas in the US [7]. Since its launch in 2014, pooled rideshare services have seen steady growth but experienced a decline from 2020 onward, largely due to the global COVID-19 pandemic. This downturn impacted TNCs. In 2020, Uber drivers completed 4.98 billion trips, marking a 27% drop from the 6.9 billion trips in 2019 [16]. Similarly, Lyft only had 12.5 million riders in the fourth quarter of 2020, a 45% decrease compared to the same period in 2019 [17]. However, post-pandemic, both Lyft and Uber began to show signs of recovery in the US. By April 2022, Uber’s sales had not only recovered but exceeded pre-pandemic levels, maintaining the highest ever usage rates throughout most of 2022 and into 2023. In 2022, Uber completed a total of 7.6 billion trips, surpassing their 2019 totals by 20.6% [18]. Nevertheless, the pandemic has led to a lasting reduction in the adoption of pooled ridesharing; for instance, only 4% of rideshare users in Chicago chose pooled rides in October 2022, a sharp decline from 17% before the pandemic [19].

1.3. Literature Review of Various Factors and Demographics Impact on Pooled Rideshare

Investigating the impact of various factors on PR usage, such as travel time preferences, cost considerations, safety concerns, and privacy needs in PR services, is essential for gaining deeper insights into user behavior and enhancing the efficacy of these services [9,13,20,21,22,23,24]. These factors significantly influence the decision-making process of potential users. By gaining a greater understanding of these influences, service providers can tailor their offerings to better meet the specific needs and concerns of different user groups. For instance, understanding that certain demographics might prioritize safety over cost can lead service providers to implement more rigorous background checks or introduce additional safety features, thereby increasing user trust and service adoption [9,13,25]. Furthermore, considerations like vehicle type and accessibility options may cater to the needs of users with disabilities, making pooled ridesharing a more inclusive service [20,21,23,26]. Analyzing how these varied influences impact user choices may help to create a more personalized and responsive pooled ridesharing ecosystem, ultimately leading to higher satisfaction and increased usage rates.

The exploration of how diverse user groups perceive and use PR services reveals significant insights that are essential for customizing and improving these services. Distinct demographic variables such as gender, age, geographic location, and income can lead to varied preferences and usage patterns in pooled ridesharing. For example, gender differences may influence the perceived safety and comfort of sharing a ride with strangers, as studies suggest females may prioritize safety more than males [9,27]. Similarly, generational differences impact technology adoption and transportation preferences, with younger individuals being more likely to embrace pooled ridesharing due to their comfort with digital platforms [28,29].

Geographic location plays a critical role. Urban residents might have different motivations for using PR compared to those in suburban or rural areas due to differences in availability and accessibility of transport options within cities [30,31]. Additionally, income levels affect transportation choices. Higher-income individuals may choose pooled rideshare for convenience reasons despite having personal vehicles, whereas lower-income users might prioritize cost savings over convenience [32]. These distinctions are crucial for service providers to understand and cater to ensure that PR services are as appealing and practical as possible. Chen et al. [33] predict an increase in PR usage in both privileged and underprivileged regions with greater precision and rationality.

Furthermore, employment status and household composition influence transportation needs and preferences. Employed adults might prioritize travel time and costs differently than retirees or those who are unable to work. For instance, households with multiple members might prefer pooled ridesharing for its cost-effectiveness or as a more convenient alternative to public transport [9]. Household vehicle ownership can influence reliance on pooled ridesharing. Households without a vehicle may view pooled rideshare as a convenient, affordable alternative to owning a car. Those households with multiple vehicles may use pooled ridesharing selectively to avoid the hassles of driving and parking in congested areas or for specific occasions when driving or parking is challenging or impractical. Additionally, environmental concerns associated with multiple vehicles may lead some to choose ridesharing for its lower environmental impact [34].

Individuals’ approach to pooled ridesharing varies by educational attainment. Those with higher education levels might be more familiar with technology and have higher disposable income, which makes them more likely to use app-based pooled ridesharing services frequently [32,35,36]. Conversely, individuals with lower education may prioritize cost over convenience, potentially finding pooled ridesharing more appealing as a cost-effective alternative to personal vehicle use or public transportation [30].

The typical transport mode used to commute plays a pivotal role in shaping the preferences and decisions of commuters towards adopting pooled rideshare services. Individuals who primarily use their personal vehicle may view PR as a way to reduce commute-related stress, save on parking fees, and mitigate the environmental impact of solo commutes [37]. However, these users may also be concerned about the potential increase in travel time due to multiple pickups and drop-offs characteristic of pooled ridesharing [30]. On the other hand, users who typically rely on public transportation may find pooled ridesharing an appealing alternative when it offers a faster or more direct route, particularly during off-peak hours when public transport schedules are less frequent [9].

For individuals who typically walk or ride a bike, opting for pooled ridesharing services might depend on factors like adverse weather conditions or the need to travel longer distances that are less feasible with walking or riding a bike. Meanwhile, telecommuters might occasionally use pooled ridesharing for meetings or work-related travel, valuing the flexibility to work en route [38]. Each of these commuting habits influences the perceived benefits and barriers to choosing PR.

Carpoolers already exhibit a willingness to share rides with others, which may make them more amenable to pooled rideshare services. However, they might seek assurances that pooled ridesharing can provide a level of convenience and reliability similar to or better than traditional carpooling setups, where schedules and routes are often more fixed and predictable [6].

Understanding these differences is not just about improving service delivery—they are also about enhancing the overall sustainability of mobility. By effectively targeting the specific needs and preferences of different demographic groups, rideshare companies can maximize usage rates, reduce the number of vehicles on the road, and contribute to environmental goals. For example, if PR options are more effectively tailored to meet the safety and convenience standards expected by various user groups, such improvements could lead to broader acceptance and regular use, thereby increasing the societal and environmental benefits of shared transportation modes [39].

Different opinions and preferences of various user groups regarding pooled ridesharing are vital for the continuous improvement, acceptance, and longevity of these services. By acknowledging and acting on users’ diverse needs, rideshare companies may enhance user satisfaction and service efficiency, thus contributing to broader transportation sustainability and urban planning objectives. The current study is the continuation of previous research, which identified factors influencing individuals’ willingness to use pooled ridesharing services through the development of the Pooled Rideshare Acceptance Model (PRAM) [40,41,42]. For a more extensive review of the functional mechanisms through which various influencing factors, such as safety, privacy, service experience, convenience, etc., operate, please see the literature reviews in [40,41,42].

1.4. Research Objectives

Despite the growing adoption of pooled rideshare services and the development of predictive models like PRAM, the purpose of this exploratory study provides insight to determine how different demographic segments influence the acceptance and perceived barriers to PR services. The previous study on the development of PRAM considered users as a homogeneous group without accounting for how age, gender, income, or commuting patterns may uniquely contribute to riders’ perceptions of safety, convenience, and service experience.

To address this gap, the current study poses two key questions: (1) How do demographic variables moderate the influence of PRAM factors on pooled rideshare acceptance? (2) Which PRAM variables show the most variation in predictive strength across different user subgroups? Multigroup analyses were conducted using the same data from the national survey. This exploratory analysis aimed to identify the influence of 16 potential moderators, spanning from demographic variables to transportation needs, on PRAM.

By answering these questions, this research aims to provide actionable insights into how service providers and policymakers can tailor pooled rideshare features, communication strategies, and implementation plans to meet the specific expectations of diverse user groups.

1.5. Pooled Rideshare Acceptance Model (PRAM)

The current study is based on the development of the Pooled Rideshare Acceptance Model (PRAM) [40]. PRAM was constructed based on data obtained from a nationwide online survey with a US sample, including 5385 participants. The primary aim of this survey was to examine the participants’ preferences regarding willingness to use PR, thus laying the foundation for understanding the factors influencing individuals’ acceptance of PR. The PRAM model, built upon two independent factor analyses, examines the factors affecting US participants’ acceptance of pooled rideshare.

1.5.1. Willingness to Consider PR Factors

In a detailed examination of factors influencing one’s willingness to consider PR, factor analyses of the national survey highlighted several considerations. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses on 25 items identified five factors: time/cost, privacy, safety, service experience, and traffic/environment [41]. First, the time/cost factor highlighted the importance of efficiency through specific items like “Travel time from door to door”, “Wait time”, and “Likelihood of on-time arrival”, as well as the cost savings, and demonstrated that users prioritize prompt and economical travel options. Second, privacy concerns were significant, with users expressing a preference for personal space and minimal interaction within the vehicle. Safety is another critical factor, where trust in the driver and fellow passengers plays a central role, reflecting widespread safety concerns that directly influence the decision to use PR. Additionally, the service experience factor, related to users’ previous interactions and perceptions of service quality and reliability, can influence users towards or against considering PR. Lastly, the traffic/environment factor addresses users’ environmental consciousness, with a focus on reducing traffic congestion and pollution. These insights collectively help to understand the various user considerations for the acceptance of PR services.

1.5.2. Optimizing Experience Factors

The exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses on 23 items related to ways to optimize one’s experience were categorized into four factors: vehicle technology/accessibility, convenience, comfort/ease of use, and passenger safety [42]. Each factor included items that impact user decisions. The vehicle technology/accessibility factor, for instance, considered the availability of automated and battery-electric vehicles, as well as accessibility features for passengers with disabilities. The convenience factor contained items like the affordability of the service, clear information about the ride, and minimized detours, ensuring that the service meets the practical needs of users efficiently. Similarly, the comfort/ease of use factor included items related to the physical comfort within the vehicle, such as adjustable seating and sufficient space for personal belongings, which are essential for a pleasant ride experience. Lastly, the passenger safety factor focused on ensuring a safe environment through measures like pre-screening of other passengers and maintaining cleanliness and sanitation in the vehicle. Pooled rideshare services may experience broader user acceptance by addressing these specific aspects.

1.5.3. PRAM Outcome

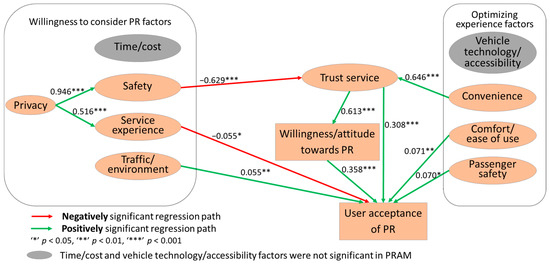

The PRAM research employed covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) to identify the potential causal relations between various factors related to the willingness to consider PR (including time/cost, privacy, safety, service experience, and traffic/environment) and optimizing the PR experience factors (comprising vehicle technology/accessibility, convenience, comfort/ease of use, and passenger safety). This ultimately culminated in identifying a higher-order factor, trust service, and assessing each factor’s relative impact on willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR, leading to the formulation of the PRAM (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pooled Rideshare Acceptance Model (PRAM) developed based on the US national survey of 5385 participants [40].

Within the PRAM framework, several factors proved to be statistically significant, including privacy, safety, trust service, and convenience, alongside comfort/ease of use, service experience, traffic/environment, and passenger safety. Interestingly, two factors, namely time/cost and vehicle technology/accessibility, were not predictive of acceptance of PR, suggesting that users primarily consider these variables once they have established a sense of safety in using PR. Despite the lack of direct significance, it is worth noting that individual components related to time and cost remain essential when examined within the broader factor of convenience [42]. This highlights the importance of addressing users’ privacy and safety perceptions as pivotal factors influencing their attitudes toward PR. Once these safety concerns are adequately addressed and the services are perceived as convenient, the time and cost elements significantly contribute to users’ trust in pooled rideshare services. This finding consistently holds throughout the study.

In more specific terms, privacy indirectly exerts a negative influence on willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR, with mediation through safety and trust service pathways. Additionally, privacy also indirectly impacts willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR; this impact is mediated through the prism of service experience. Safety, on the other hand, indirectly affects willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR, with its influence channeled through the trust service factor. Trust service itself directly and positively affects user acceptance of PR, with an added positive indirect influence mediated through willingness/attitude towards PR. Moreover, convenience indirectly contributes to willingness/attitude towards PR and user acceptance of PR, with its impact channeled through the trust service factor.

When considering other factors from willingness to consider PR, service experience has a direct negative influence on user acceptance of PR, while traffic/environment has a direct positive impact on user acceptance of PR. Similarly, within the optimizing experience domain, comfort/ease of use positively and directly influences user acceptance of PR, while passenger safety also directly and positively influences user acceptance of PR. In summary, information related to the ride, such as cost, route, and time, service transparency, and the ability for users to communicate with the outside world significantly influence the acceptance of PR. Individuals tend to view privacy, safety, and service experience as factors that may discourage them from choosing PR over other transportation modes.

1.6. Exploring Opportunities for Further Analysis: Examining Moderators in the PRAM

Multigroup analyses were conducted using the same data from the national survey. This analysis aimed to explore the influence of 16 potential moderators, spanning from demographic variables to transportation needs, on PRAM. By understanding the impact of these moderators, this study can provide a more detailed perspective on rideshare acceptance.

1.7. Moderation Analysis (Single Versus Multiple Group)

In Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), researchers have the option of conducting either a single-group or multigroup analysis [43]. A single-group analysis involves testing the model with a single respondent group at a time, focusing on examining the direct and indirect connections between variables specific to that group. Conversely, multigroup analysis in SEM is utilized when the objective is to compare the model across two or more distinct groups, such as different age groups or educational levels. In this case, the goal was to assess the model’s fit for each demographic group and ascertain if there were significant variations in the relationships between variables within each group. Therefore, while single-group SEM sheds light on variable relationships within a particular group, multigroup SEM provides valuable comparative insights across groups. For the current study, the multigroup analysis was appropriate to analyze each moderator based on the multiple groups within a given moderator.

2. Methods

2.1. Survey Design

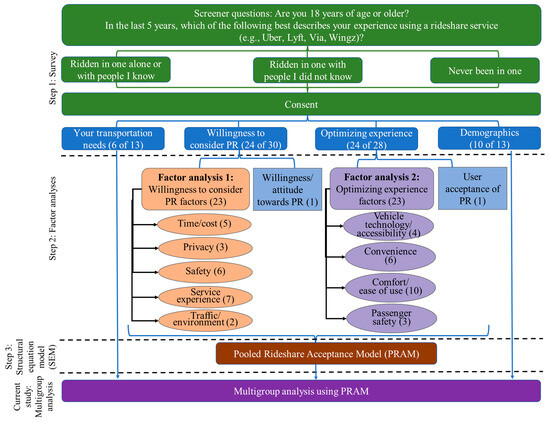

The multigroup analysis was completed using 5385 participants, including 2000 nationwide participants with roughly 500 additional participants each from Atlanta, Austin, Chicago, Detroit, New York City, and San Francisco, plus 384 participants from Upstate South Carolina. The survey structure and the data analysis process are shown in Figure 2. Potential participants first confirmed they were 18 years of age or older. Next, baseline experience with rideshare was used for recruitment or sampling purposes. Then, potential participants provided their consent to be part of the study. The first section included questions to assess participants’ transportation needs. This section explored their needs as well as their experience with various transportation services. In the second section of questions, participants reported their willingness to consider utilizing PR; please refer to Section 1.5.1. for more details. The third section focused on survey items about optimizing one’s experience using PR; please see Section 1.5.2. for more information. The final section included demographic questions.

Figure 2.

Step 1 displays the structure of the survey. The numbers in parentheses in the willingness to consider PR and optimizing experience sections are the number of survey items used in the PRAM. The numbers in parentheses in your transportation needs and demographics sections are the number of survey items explored as potential moderators for the multigroup analysis. Factor analyses and SEM statistical methods were used to develop PRAM. The current study uses demographic data from the survey to conduct multigroup analyses using PRAM.

This study explored the impact of select items from the two sections of the survey, specifically your transportation needs, using six of the 13 items, and demographics, using 10 of the 13 items in that section, to determine their influence on the PRAM. Refer to Section 1.5.3. for the PRAM model development. The combination of responses from your transportation needs and demographics were combined into the demographic topics explored in this multigroup analysis. These items served as potential moderators in PRAM.

2.2. Potential Moderators

The participants’ distribution is listed in Table 1. The total sample was grouped into 16 different categories based on their demographics and transportation needs; each of these categories was explored as a possible moderator. The first two moderators were the participant’s gender and age. Of the 5385 participants, 52.1% were female, 47.3% were male, and 0.3% preferred self-describing. Overall, participants had a mean age of 46.5 (SD = 17.5), ranging from 18 to 95 years. The participant’s age distribution was grouped based on generation. Each generation had a sample distribution of more than 15%, except for the pre-boomers group (4.7%). The third moderator was living area; most of the participants were from suburban (54.9%) and urban (37.8%) areas. A driver’s license was the fourth moderator; 89.2% of participants had a license. The fifth moderator was the participants’ experience using rideshare as a rider, where 43.3% of participants had no previous rideshare experience. The sixth moderator focused on participants’ level of school completion, which ranged from 22.7% of participants with some college to 27.9% of participants with some graduate school or an advanced degree. Next, the participants indicated their employment status. The majority of the participants were employed (57.5%) or retired (22.1%). The eighth moderator was the number of people living in the household, including the participant. The sample included one (19.9%), two (33.9%), three (18.3%), or more than three (27.5%) individuals. Then, the ninth moderator was the number of children under the age of 18 living in the household. Most of the participants had zero (66.5%) children. The tenth moderator was based on the household’s annual income before taxes. There were 39.9% in the USD 25k to under USD 80k group, followed by 26.8% in the USD 80k to under USD 150k group. The eleventh moderator was based on the number of vehicles owned or leased by household members. Most of the participants had one vehicle (40.8%), followed by two vehicles (35.3%). The twelfth to sixteenth moderators were related to transportation. The participants were asked about the different types of transportation typically used in their daily commute. The twelfth moderator was grouped as those who use a personal vehicle for their daily commute, 80.7%. The remaining moderators focused on other forms of transportation used for commuting, such as public transport (20.6%), walk/bike (34.4%), telecommute (10.1%), and carpooling (11.9%).

Table 1.

Distribution of participants based on their demographics and transportation needs.

2.3. Data Analysis Process

A multigroup SEM was conducted to assess the moderating effects of the 16 potential moderators on the pooled rideshare acceptance model (PRAM). The analyses were conducted in R using the lavaan package [44,45]. The lavaan fully supports multiple groups’ analysis of data using the CB-SEM approach. This study is the follow-up analysis of the full model obtained in the PRAM [40]. For the multigroup moderation using CB-SEM, all the moderators were assumed to be categorical to separate the responses into groups at each moderator level. The multigroup moderation was conducted hierarchically.

First, each potential moderator was imposed on the full PRAM model as an unconstrained regression model. In the unconstrained model, all the regression path coefficients were allowed to be freely estimated in the groups. Then, all regression path loadings were constrained to be equal across groups to find the significant group difference over the full model, termed a constrained regression model. For the model comparison, the chi-square difference test was conducted to determine whether there was a difference in the fit of the models between the unconstrained and constrained models due to the moderator [46,47]. However, because the models included causal structural relations and their relative contributions towards different paths, it was important to understand the strength of the relationship between the individual regression paths when imposed with a moderator rather than for the full model. Therefore, the full model was constrained to one regression path coefficient at a time, and the chi-square was conducted between the unconstrained and one regression path coefficient constrained model [48]. This importantly provided the statistically significant difference between the groups in a moderator for a particular regression path. This analysis was completed for all 11 regression paths individually. Various goodness-of-fit indices were used to evaluate the model’s fit. Based on the existing literature, the goodness-of-fit indices should meet the following criteria: Comparative Fit Index (CFI) > 0.8 [49], Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08 [50], Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) < 0.08 [51], and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) > 0.8 [49]. The chi-square difference test (∆χ2) and its significance at the 5% level were also reported.

After identifying the significant difference between the groups for a given moderator, the next step was the post hoc analysis to identify if levels of the moderator were significantly different from one another, particularly when there were more than two groups for a moderator. If there were more than two groups, and if the model comparison analysis had indicated there was a significant difference between the groups, then the model comparison using the chi-square difference test was made for the different groups within a moderator. The standardized path coefficient estimation of the multiple group models in the moderator for the different significant regression paths was reported in the result. Out of 11 regression paths in the PRAM, the two regression paths safety → trust service and service experience → user acceptance of PR had a negative relationship, which means the safety concern factor negatively influenced the trust in the service (safety → trust service) and lack of better service experience compared to other transportation modes negatively influenced the PR acceptance (service experience → user acceptance of PR). Therefore, for these two regression paths, standardized path coefficient estimation explains the negative relative differences between the groups.

3. Results and Discussion

The multigroup moderation analysis was conducted on the full model obtained in the PRAM using the moderators listed in Table 1. The sections below explain the results of each moderator’s influence on the relationship between the variables with a significant path in the PRAM model. A summary of these results is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the moderator’s influence on the PRAM.

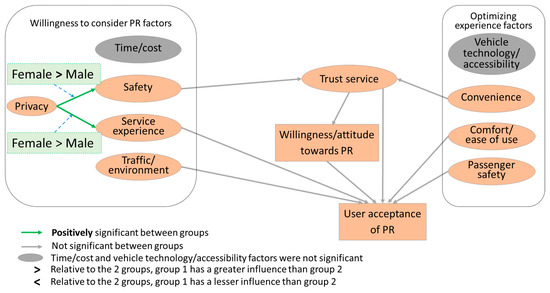

3.1. Gender

In PRAM, safety was an issue for everyone; as a result, gender was further explored. The gender moderator consisted of two groups: (1) male and (2) female. Using the hierarchal approach of model comparison, first, the unconstrained model and the 11 individual regression paths of constrained models that were significant in PRAM were compared. Table 3 shows the regression paths that were significantly different from the unconstrained model. The privacy → safety (∆χ2 = 4.399, p < 0.05) and privacy → service experience (∆χ2 = 16.609, p < 0.001) regression paths were significantly different from the unconstrained model, indicating that the moderator, gender, influenced these two paths.

Table 3.

Multigroup analysis of gender highlighting significant paths.

Next, the group differences using the model comparison were obtained for the two significant regression paths, see Figure 3. Privacy had a greater influence on safety for females (β = 1.004) compared to males (β = 0.877). Similarly, privacy had a greater influence on service experience for females (β = 0.608) compared to males (β = 0.422).

Figure 3.

The gender moderator influenced two regression paths.

The moderator gender (males and females) significantly influenced two regression paths: privacy → safety and privacy → service experience. The influence of gender as a moderator significantly differs between privacy and safety, as well as between privacy and service experience. While PRAM demonstrates that privacy has a positive relation with both safety and service experience, these positive relations were stronger for females than males. This suggests that for female participants, an increased sense of privacy notably enhances their perception of safety and their overall service experience. These findings underline the critical role of gender-based preferences, concerning privacy considerations. Further, this suggests the need for tailored strategies that account for these different privacy needs is worth further exploration.

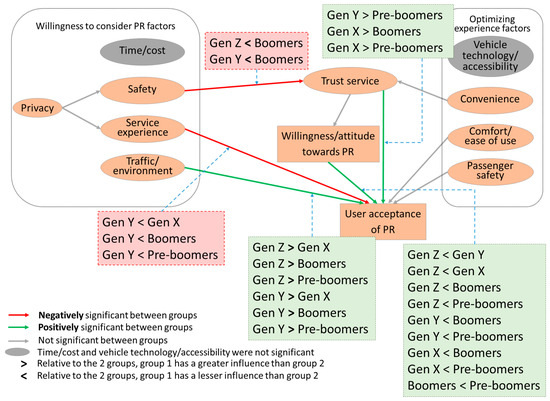

3.2. Generation

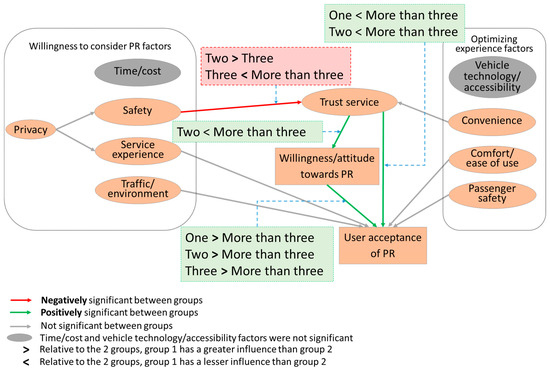

The generation moderator consisted of five groups: (1) gen Z (<27 years), (2) gen Y (27–44 years), (3) gen X (45–56 years), (4) boomers (57–75 years), and (5) pre-boomers (>75 years). Table 4(A) shows the regression paths that were significantly different from the unconstrained model. The safety → trust service (∆χ2 = 11.075, p < 0.05), service experience → user acceptance of PR (∆χ2 = 11.356, p < 0.05), traffic/environment → user acceptance of PR (∆χ2 = 15.447, p < 0.01), trust service → user acceptance of PR (∆χ2 = 14.002, p < 0.01), and willingness/attitude towards PR → user acceptance of PR (∆χ2 = 46.165, p < 0.001) regression paths were significantly different from the unconstrained model, indicating the moderator, generation, influenced these five paths.

Table 4.

(A) Multigroup analysis of generation highlighting significant paths. (B) Analysis of group differences in significant paths.

Next, the group differences were obtained using model comparisons to identify the significant regression paths, as shown in Table 4(B) and Figure 4. In comparison to gen Z (β = −0.828), safety had a greater negative influence on trust service for boomers (β = −1.019). Similarly, compared to gen Y (β = −0.609), safety had a greater negative influence on trust service for boomers (β = −1.019). Service experience had a greater negative influence on user acceptance of PR for gen X (β = 0.009) when compared to gen Y (β = −0.198). Service experience had a greater negative influence on user acceptance of PR for boomers (β = −0.016) when compared to gen Y (β = −0.198). Service experience had a greater negative influence on user acceptance of PR for pre-boomers (β = 0.137) when compared to gen Y (β = −0.198). Traffic/environment had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for gen Z (β = 0.218) compared to gen X (β = −0.014). Similarly, traffic/environment had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for gen Z (β = 0.218) compared to boomers (β = 0.033). Traffic/environment had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for gen Z (β = 0.218) compared to pre-boomers (β = 0.06). Similar to gen Z, traffic/environment had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for gen Y (β = 0.136) compared to gen X (β = −0.014). Traffic/environment had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for gen Y (β = 0.136) compared to boomers (β = 0.033). Traffic/environment had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for gen Y (β = 0.136) compared to pre-boomers (β = 0.06). Trust service had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for gen Y (β = 0.312) when compared to pre-boomers (β = 0.085). Gen X (β = 0.292) had trust service as a greater influence on user acceptance of PR when compared to boomers (β = 0.264). Gen X (β = 0.292) had trust service as a greater influence on user acceptance of PR when compared to pre-boomers (β = 0.085). Willingness/attitude towards PR had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for gen Y (β = 0.35) when compared to gen Z (β = 0.221). Similarly, willingness/attitude towards PR had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for gen X (β = 0.357) when compared to gen Z (β = 0.221). Willingness/attitude towards PR had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for boomers (β = 0.416) when compared to gen Z (β = 0.221). Willingness/attitude towards PR had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for pre-boomers (β = 0.546) when compared to gen Z (β = 0.221). Willingness/attitude towards PR had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for boomers (β = 0.416) when compared to gen Y (β = 0.35). Willingness/attitude towards PR had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for pre-boomers (β = 0.546) when compared to gen Y (β = 0.35). Similar to gen Z and gen Y, willingness/attitude towards PR had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for boomers (β = 0.416) when compared to gen X (β = 0.357). Willingness/attitude towards PR had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for pre-boomers (β = 0.546) when compared to gen X (β = 0.357). Lastly, willingness/attitude towards PR had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for pre-boomers (β = 0.546) when compared to boomers (β = 0.416).

Figure 4.

The generation moderator influenced five regression paths.

The moderator generation (gen z, gen y, gen x, boomers, and pre-boomers) significantly influenced five regression paths: safety → trust service, service experience → user acceptance of PR, traffic/environment → user acceptance of PR, trust service → user acceptance of PR, and willingness/attitude towards PR → user acceptance of PR. The youngest generation, gen Z was more willing to use PR than the older generations. Out of the five age groups, safety had a larger influence on boomers. Willingness to use PR had a larger influence for boomers and pre-boomers if they consider accepting PR.

Addressing safety concerns is key to gaining the trust of the boomer generation, while enhancing the service experience may be more valuable in attracting users from gen X, boomers, and pre-boomers. For gen Z and gen y users, emphasizing the potential for a positive environmental impact and reduced traffic congestion may be more influential. In terms of trust in PR service, this factor is essential to influence gen Y, gen X, and pre-boomers, suggesting that these generations place higher importance on reliable and high-quality service. The willingness and attitude towards PR are significant across all generations except gen Z, but they appear to hold a more prominent role for boomers and pre-boomers in terms of their acceptance of PR. These findings suggest that addressing the unique concerns and preferences of each generation is important to consider because a “one size fits all” approach will not work. Yet, considering the unique needs of each generation may effectively promote the acceptance and usage of PR.

3.3. Geographic Area

The geographic area moderator consisted of three groups: (1) urban, (2) suburban, and (3) rural. The chi-square model comparison showed no significant differences between the unconstrained model to when the 11 regression paths were constrained individually. Since there was no significant difference between the three groups, the moderator was then grouped into two groups: (1) urban (38%) and (2) suburban or rural (62%) to identify if there were any differences. When examining the two groups, the chi-square model comparison showed no significant difference between the unconstrained model to when the 11 regression paths were constrained individually. Therefore, the findings from the study do not support a different strategy based upon one’s geographic area, and the relationship between the factors was consistent across the three different geographic areas.

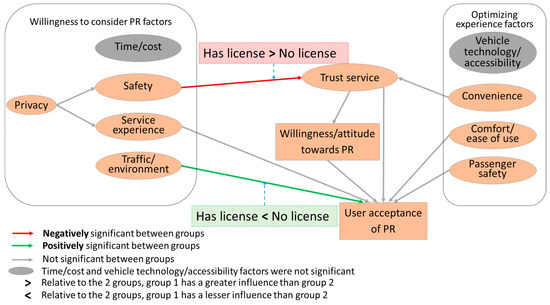

3.4. Driver’s License

The driver’s license moderator consisted of two groups (1) has license and (2) no license. Table 5 shows the regression paths that were significantly different from the unconstrained model. The safety → trust service (∆χ2 = 5.658, p < 0.05) and traffic/environment → user acceptance of PR (∆χ2 = 4.204, p < 0.05) regression paths were significantly different from the unconstrained model, indicating the moderator, driver’s license, influenced these two paths.

Table 5.

Multigroup analysis of driver’s license highlighting significant paths.

Next, the group differences using model comparison were obtained for the significant regression paths, see Figure 5. Safety had a greater negative influence on trust service for the has license (β = −0.666) group compared to the no license (β = −0.626) group. In comparison to the has license group (β = 0.043), traffic/environment had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for the no license (β = 0.189) group.

Figure 5.

The driver’s license moderator influenced two regression paths.

These findings suggest differing priorities between individuals possessing a driver’s license and those without. Those with a driver’s license placed a higher emphasis on safety aspects when establishing trust in PR services, which suggests that addressing safety concerns might be particularly effective in increasing PR acceptance among license holders. Individuals without a driver’s license demonstrated a greater sensitivity to traffic and environmental factors in their acceptance of PR services. Therefore, emphasizing the positive impact of PR services on traffic reduction and environmental sustainability may influence this group more effectively.

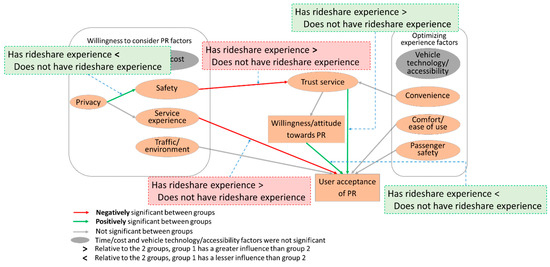

3.5. Rideshare Experience

The rideshare experience moderator consisted of two groups: (1) has rideshare experience and (2) does not have rideshare experience. Table 6 shows the regression paths that were significantly different from the unconstrained model. The privacy → safety (∆χ2 = 6.982, p < 0.01), safety → trust service (∆χ2 = 4.196, p < 0.05), service experience → user acceptance of PR (∆χ2 = 6.517, p < 0.05), trust service → willingness/attitude towards PR (∆χ2 = 4.713, p < 0.05), and willingness/attitude towards PR → user acceptance of PR (∆χ2 = 12.562, p < 0.001) regression paths were significantly different from the unconstrained model, indicating the moderator, rideshare experience, influenced these five paths.

Table 6.

Multigroup analysis of rideshare experience highlighting significant paths.

Next, the group differences using model comparison were obtained for the significant regression paths (see Figure 6). In comparison to the has rideshare experience (β = 0.985) group, privacy had a greater influence on safety for the does not have rideshare experience (β = 0.987) group. In comparison to the does not have rideshare experience group (β = −0.596), safety had a greater negative influence on trust service for the has rideshare experience (β = −0.806) group. In comparison to the does not have rideshare experience group (β = −0.003), service experience had a greater negative influence on user acceptance of PR for the has rideshare experience group (β = −0.123). In comparison to the does not have rideshare experience group (β = 0.473), trust service had a greater influence on willingness towards PR for the has rideshare experience (β = 0.64) group. In comparison to the has rideshare experience group (β = 0.315), willingness towards PR had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for the does not have rideshare experience (β = 0.351) group.

Figure 6.

The rideshare experience moderator influenced five regression paths.

The influence of different factors on perceptions and behaviors towards PR adoption differs considerably between users with and without previous rideshare experience. For those without prior rideshare experience, privacy appears to be a primary concern that significantly influences their perceptions regarding safety. This implies that in order to attract new users, it may be crucial to proactively address these potential riders’ privacy concerns. For experienced rideshare users, safety concerns have a significant negative impact on trust in PR services, implying that these riders prioritize safety and expect reliable, trustworthy services. The overall service experience is also different between these two groups. Among users with rideshare experience, service experience has a greater negative influence on their acceptance of PR, suggesting that efforts to retain these riders should prioritize improving the overall service experience. Similarly, trust in PR services has a greater positive influence on experienced users’ willingness towards PR, further reinforcing the importance of building and maintaining trust among these riders. The willingness towards PR emerges as an influential factor for users without rideshare experience, with a significant positive influence on their acceptance of PR. This finding shows the importance of effectively promoting the benefits of PR to potential new users in order to positively influence their acceptance of PR services.

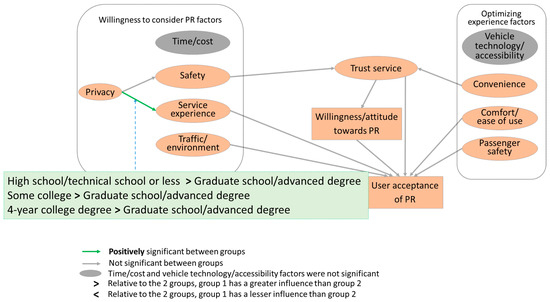

3.6. School Completion

The school completion moderator consisted of four groups: (1) high school/technical school or less, (2) some college, (3) 4-year college degree, and (4) graduate school/advanced degree. Table 7(A) shows the regression paths that were significantly different from the unconstrained model. The privacy → service experience (∆χ2 = 31.169, p < 0.001) regression path was significantly different from the unconstrained model, indicating the moderator, school completion, influenced this one path.

Table 7.

(A) Multigroup analysis of school completion highlighting a significant path. (B) Analysis of group differences in a significant path.

Next, the group differences using model comparison were obtained for the significant regression paths, as shown in Table 7(B) and Figure 7. In comparison to high school/technical school or less (β = 0.543) respondents, privacy had a lesser influence on service experience for the graduate school/advanced degree (β = 0.369) respondents. In comparison to some college (β = 0.598) respondents, privacy had a lesser influence on service experience for graduate school/advanced degree (β = 0.369) respondents. In comparison to 4-year college degree (β = 0.691) respondents, privacy had a lesser influence on service experience for graduate school/advanced degree (β = 0.369) respondents.

Figure 7.

The school completion moderator influenced one regression path.

Those individuals with higher education levels, specifically those riders with an advanced degree, reported less concerns about privacy when evaluating service experiences related to PR services in comparison to riders with less education. This tendency may imply that those individuals with an advanced degree may have a more comprehensive understanding of privacy policies and security measures associated with PR services, or that they do not have the same biases or concerns as the other riders with less education. Regardless, this divergence in privacy concerns highlights the diverse ways in which different groups approach and interact with PR services and demonstrates the need for varying approaches to address privacy concerns with PR for potential riders with different educational backgrounds rather than a “one size fits all” approach.

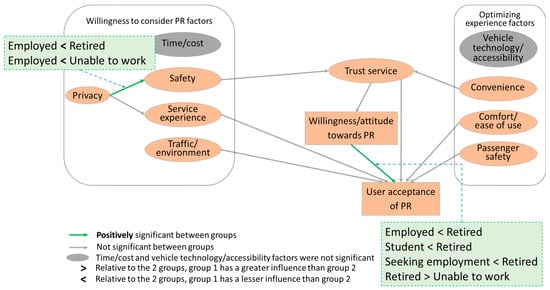

3.7. Employment Status

The employment status moderator consisted of six groups: (1) employed, (2) student, (3) student employed, (4) seeking employment, (5) retired, and (6) unable to work. Table 8(A) shows the regression paths that were significantly different from the unconstrained model. The privacy → safety (∆χ2 = 107.227, p < 0.001) and willingness/attitude towards PR → user acceptance of PR (∆χ2 = 31.523, p < 0.001) regression paths were significantly different from the unconstrained model, indicating the moderator, employment status, influenced these two paths.

Table 8.

(A) Multigroup analysis of employment status highlighting significant paths. (B) Analysis of group differences in significant paths.

Next, the group differences using the model comparison were obtained for the significant regression paths, as shown in Table 8(B) and Figure 8. In comparison to retired (β = 1.297), privacy had a lesser influence on safety for the employed (β = 0.882) group. Similarly, in comparison to unable to work (β = 0.922), privacy had a lesser influence on safety for the employed (β = 0.882) group. In comparison to employed (β = 0.34), willingness/attitude towards PR had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for the retired (β = 0.454) group. In comparison to student (β = 0.269), willingness/attitude towards PR had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for the retired (β = 0.454) group. In comparison to seeking employment (β = 0.251), willingness/attitude towards PR had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for the retired (β = 0.454) group. In comparison to unable to work respondents (β = 0.249), willingness/attitude towards PR had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for the retired (β = 0.454) group.

Figure 8.

The employment status moderator influenced two regression paths.

When examining the role of employment status in the context of PR services, it was observed that the employed individuals are less concerned about privacy as compared to their retired or unable to work counterparts. This may indicate different priorities, biases, or risk perceptions between these groups. On the other hand, the willingness or positive attitude towards PR services holds a greater influence for the retired group than for employed individuals, students, those seeking employment, and individuals unable to work. This may suggest a potential openness or receptivity to PR services among retired individuals, perhaps due to different lifestyles, fewer time demands, or transportation preferences. Alternatively, retired individuals may face age-related challenges that their younger peers do not and may be open to alternative forms of transportation if they have retired from driving or see peers who are no longer able to drive. Understanding these differences in privacy concerns based upon one’s stage in life and willingness to use PR, based on employment status, may provide valuable insights for targeted service improvements and/or promotional strategies.

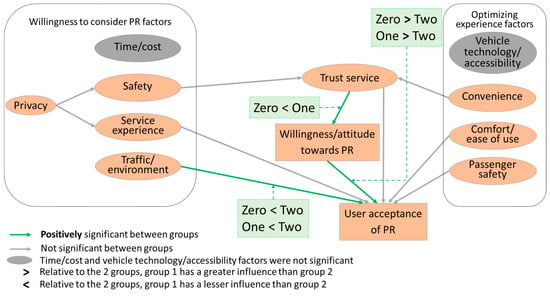

3.8. Number of People in the Household

The number of people in the household moderator consisted of four groups: (1) one, (2) two, (3) three, and (4) more than three. Table 9(A) shows the regression paths that were significantly different from the unconstrained model. The safety → trust service (∆χ2 = 9.354, p < 0.05), trust service → willingness/attitude towards PR (∆χ2 = 84.601, p < 0.001), trust service → user acceptance of PR (∆χ2 = 7.962, p < 0.05), and willingness/attitude towards PR → user acceptance of PR (∆χ2 = 14.164, p < 0.01) regression paths were significantly different from the unconstrained model, indicating the moderator, number of people in the household, influenced these four paths.

Table 9.

(A) Multigroup analysis of number of people in the household highlighting significant paths. (B) Analysis of group differences in significant paths.

Next, the group differences using model comparison were obtained for the significant regression paths, as shown in Table 9(B) and Figure 9. In comparison to two (β = −0.733) people in the household, safety had a lesser negative influence on trust service for three (β = −0.496) people in the household. In comparison to three (β = −0.496) people in the household, safety had a greater negative influence on trust service for more than three (β = −0.839) people in the household. In comparison to two (β = 0.597) people in the household, trust service had a greater influence on willingness/attitude towards PR for more than three (β = 0.602) people in the household. In comparison to one (β = 0.251) person in the household, trust service had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for more than three (β = 0.349) people in the household. Similarly, in comparison to two (β = 0.273) people in the household, trust service had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for more than three (β = 0.349) people in the household. In comparison to one (β = 0.406) person in the household, willingness/attitude towards PR had a lesser influence on user acceptance of PR for more than three (β = 0.287) people in the household. In comparison to two (β = 0.378) people in the household, willingness/attitude towards PR had a lesser influence on user acceptance of PR for more than three (β = 0.287) people in the household. In comparison to three (β = 0.377) people in the household, willingness/attitude towards PR had a lesser influence on user acceptance of PR for more than three (β = 0.287) people in the household.

Figure 9.

The number of people in the household moderator influenced four regression paths.

When comparing the impact of various factors across households of different sizes, some important findings were identified. For households with more than three people, the importance of safety has a more pronounced negative effect on trust in PR services compared to those households with two or three members. Similarly, in larger households (more than three people), the influence of trust in the service on their willingness or attitude towards PR is stronger when compared to those households with only two people. This heightened trust also extends to user acceptance of PR, where larger households exhibit a stronger relationship between trust in the service and acceptance of PR, compared to households comprising one or two individuals. When it comes to the impact of willingness or attitude towards PR on its acceptance, households with more than three people show a smaller influence of willingness or attitude towards PR on its acceptance when compared to households with one, two, or three people. These observations suggest that the size of the household may strongly influence a household’s perceptions and acceptance of PR services.

3.9. Number of Children

The number of children moderator consisted of four groups: (1) zero, (2) one, (3) two, and (4) more than two. Table 10(A) shows the regression paths that were significantly different from the unconstrained model. The traffic/environment → user acceptance of PR (∆χ2 = 10.636, p < 0.05), trust service → willingness/attitude towards PR (∆χ2 = 10.672, p < 0.05), and willingness/attitude towards PR → user acceptance of PR (∆χ2 = 34.779, p < 0.001) regression paths were significantly different from the unconstrained model, indicating the moderator number of children influenced these three paths.

Table 10.

(A) Multigroup analysis of number of children highlighting significant paths. (B) Analysis of group differences in significant paths.

Next, the group differences using model comparison were obtained for the significant regression paths, as shown in Table 10(B) and Figure 10. In comparison to zero (β = 0.034) children in the household, traffic/environment had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for two (β = 0.23) children in the household. Similarly, in comparison to one (β = 0.038) child, traffic/environment had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for two (β = 0.23) children. In comparison to zero (β = 0.578) children, trust service had a greater influence on willingness towards PR for a family with one (β = 0.636) child. In comparison to zero (β = 0.393) children, willingness towards PR had a lesser influence on user acceptance of PR for two (β = 0.179) children. Similarly, in comparison to one (β = 0.345) child, willingness towards PR had a lesser influence on user acceptance of PR for two (β = 0.179) children in the household.

Figure 10.

The number of children moderator influenced three regression paths.

The analysis of the influence of the number of children in a household on the acceptance and utilization of PR services reveals significant implications. Different family sizes exhibit varying attitudes and priorities when considering PR services. Households with two children place more emphasis on traffic and environmental considerations, while trust in PR service is more prominent for families with one child. Additionally, the willingness to use PR services does not necessarily translate into acceptance for larger families, highlighting the complexity of decision-making processes in these groups. For example, larger families may have specific safety and logistical requirements that are not being met by existing PR services, such as not enough room for multiple car seats. These findings emphasize the need for PR service providers to understand that family size is not just a demographic attribute but a significant factor that influences transportation preferences and requirements, thus necessitating tailored strategies to meet the needs of different family groups.

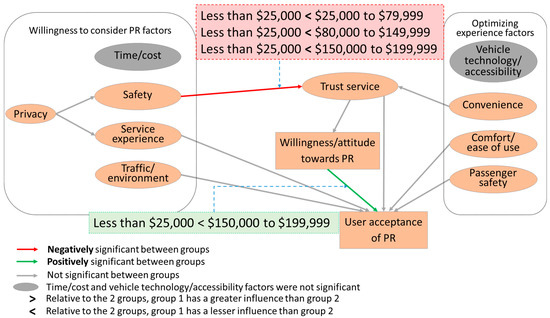

3.10. Household Annual Income

The household annual income moderator consisted of six groups: (1) less than USD 25,000, (2) USD 25,000 to USD 79,999, (3) USD 80,000 to USD 149,999, (4) USD 150,000 to USD 199,999, (5) USD 200,000 to USD 249,999, and (6) USD 250,000 or more. Table 11(A) shows the regression paths that were significantly different from the unconstrained model. The safety → trust service (∆χ2 = 25.445, p < 0.001) and willingness/attitude towards PR → user acceptance of PR (∆χ2 = 16.116, p < 0.01) regression paths were significantly different from the unconstrained model, indicating the moderator, household annual income, influenced these two paths.

Table 11.

(A) Multigroup analysis of household annual income highlighting significant paths. (B) Analysis of group differences in significant paths.

Next, the group differences using model comparison were obtained for the significant regression paths, as shown in Table 11(B) and Figure 11. In comparison to the less than USD 25,000 (β = −0.716) household annual income, safety had a greater negative influence on trust service for the USD 25,000 to USD 79,999 (β = −0.798) household annual income. In comparison to the less than USD 25,000 (β = −0.716) household annual income, safety had a greater negative influence on trust service for the USD 80,000 to USD 149,999 (β = −0.788) household annual income. Similarly, in comparison to the less than USD 25,000 (β = −0.716) household annual income, safety had a greater negative influence on trust service for the USD 150,000 to USD 199,999 (β = −0.723) household annual income. In comparison to the less than USD 25,000 (β = 0.297) household annual income, willingness/attitude towards PR had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for the USD 150,000 to USD 199,999 (β = 0.496) household annual income.

Figure 11.

The household annual income moderator influenced two regression paths.

The findings related to household annual income and its influence on the acceptance of PR services highlight variations in different income groups. Specifically, the relationship between safety and trust in PR services is negatively influenced to a greater degree in the income brackets ranging from USD 25k to less than USD 200k when compared to households earning less than USD 25k. Willingness and attitude towards PR have a stronger influence on user acceptance of PR for households earning USD 150k to less than USD 200k. These insights indicate that the perception of safety and the propensity to adopt PR services are not uniform across income levels but are instead influenced by specific financial circumstances. This understanding necessitates that PR providers develop targeted strategies that recognize and respond to the varying attitudes and concerns of users across different income brackets, with particular attention to safety perceptions and the factors that promote willingness to use PR services.

3.11. Number of Vehicles

The number of vehicles moderator consisted of four groups: (1) zero, (2) one, (3) two, and (4) more than two. Table 12(A) shows the regression paths that were significantly different from the unconstrained model. The safety → trust service (∆χ2 = 19.100, p < 0.001) and willingness/attitude towards PR → user acceptance of PR (∆χ2 = 15.253, p < 0.01) regression paths were significantly different from the unconstrained model, indicating the moderator, number of vehicles, influenced these two paths.

Table 12.

(A) Multigroup analysis of number of vehicles highlighting significant paths. (B) Analysis of group differences in significant paths.

Next, the group differences using model comparison were obtained for the significant regression paths, as shown in Table 12(B) and Figure 12. Safety had a greater negative influence on trust service for two (β = −0.717) vehicles in the household when compared to zero (β = −0.467) vehicles. Similarly, safety had a greater negative influence on trust service for two (β = −0.717) vehicles in the household when compared to one (β = −0.591) vehicle. Safety had a greater negative influence on trust service for more than two (β = −0.893) vehicles in the household when compared to zero (β = −0.467) vehicles. Similarly, safety had a greater negative influence on trust service for more than two (β = −0.893) vehicles in the household when compared to one (β = −0.591) vehicle. In comparison to zero (β = 0.432), one (β = 0.377), and two (β = 0.374) vehicles in the household, willingness/attitude towards PR had a lesser influence on user acceptance of PR for more than two (β = 0.217) vehicles in the household.

Figure 12.

The number of vehicles moderator influenced two regression paths.

The analysis of the number of vehicles as a moderating variable suggests significant variations in how safety and willingness towards PR services impact user acceptance across different groups. Safety has a greater negative impact on trust for households with two or more vehicles than for those with fewer vehicles. Conversely, willingness and attitude towards PR services have a lower influence on user acceptance in households with more than two vehicles. These findings imply that households with more vehicles may have greater concerns about safety, causing a decrease in trust towards PR services. Consequently, PR service providers need to tailor their strategies to enhance user acceptance by focusing on addressing safety concerns, particularly for households with more vehicles. Furthermore, marketing strategies should be more diversified to attract households with various numbers of vehicles, considering the variations in safety and willingness on user acceptance.

3.12. Typical Transport Mode Used to Commute

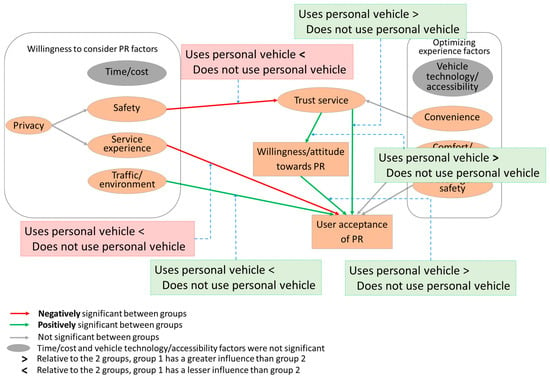

3.12.1. Personal Vehicle

The personal vehicle moderator consisted of two groups: (1) uses personal vehicle and (2) does not use personal vehicle. Table 13 shows the regression paths that were significantly different from the unconstrained model. The safety → trust service (∆χ2 = 4.525, p < 0.05), service experience → user acceptance of PR (∆χ2 = 5.591, p < 0.05), traffic/environment → user acceptance of PR (∆χ2 = 4.591, p < 0.05), trust service → willingness/attitude towards PR (∆χ2 = 4.144, p < 0.05), trust service → user acceptance of PR (∆χ2 = 4.423, p < 0.05), and willingness/attitude towards PR → user acceptance of PR (∆χ2 = 9.584, p < 0.01) regression paths were significantly different from the unconstrained model, indicating the moderator, personal vehicle, influenced these six paths.

Table 13.

Multigroup analysis of personal vehicle highlighting significant paths.

Next, the group differences using model comparison were obtained for the significant regression paths; see Figure 13. Safety had a greater negative influence on trust service for the does not use personal vehicle group (β = −1.283) compared to the uses personal vehicle group (β = −0.705). Service experience had a greater negative influence on user acceptance of PR for the does not use personal vehicle group (β = −0.053) when compared to the group that uses personal vehicle (β = −0.018). In comparison to the uses personal vehicle group (β = 0.039), traffic/environment had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for the does not use personal vehicle group (β = 0.045). In comparison to the does not use personal vehicle group (β = 0.474), trust service had a greater influence on willingness/attitude towards PR for uses personal vehicle group (β = 0.629). In comparison to the does not use personal vehicle group (β = 0.244), trust service had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for the uses personal vehicle (β = 0.293) group. In comparison to the does not use personal vehicle group (β = 0.357), willingness/attitude towards PR had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for the uses personal vehicle group (β = 0.379).

Figure 13.

The personal vehicle moderator influenced six regression paths.

The use of personal vehicles appears to strongly influence attitudes and perceptions towards PR services. For individuals who do not typically use personal vehicles, safety has a stronger negative influence on trust in PR services. Additionally, this group gives more weight to their service experience and traffic or environmental conditions in their acceptance of PR services. This suggests that these individuals are more accustomed to the quality of service and environmental impact, possibly because they rely on public or alternative transportation modes more frequently, as these were the highest factor loading items for the service experience factor [41]. In contrast, for those who do use personal vehicles, trust in PR services plays a more substantial role in shaping their willingness and acceptance towards PR services. This implies a need for strong reliability and trust in any alternative to personal vehicle use for this group. Their willingness or positive attitude towards PR also has more of an influence on their acceptance of PR services, which might suggest that these individuals could be more open to trying PR services if their initial perceptions and attitudes are positive. These variations highlight the importance of understanding the differing needs and priorities of these groups, which could be instrumental in shaping strategies to promote PR acceptance.

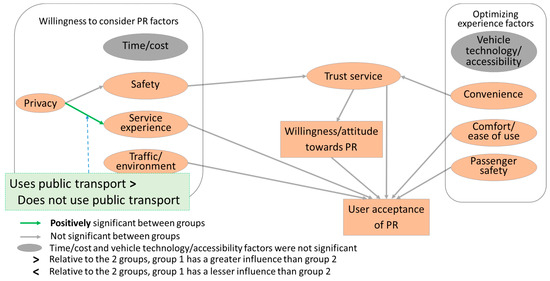

3.12.2. Public Transport

The public transport moderator consisted of two groups: (1) uses public transport and (2) does not use public transport. Table 14 shows the regression paths that were significantly different from the unconstrained model. The privacy → service experience (∆χ2 = 18.015, p < 0.001) regression path was significantly different from the unconstrained model, indicating the moderator, public transport, influenced this one path.

Table 14.

Multigroup analysis of public transport highlighting a significant path.

Next, the group differences using model comparison were obtained for the significant regression paths; see Figure 14. In comparison to the does not use public transport group (β = 0.504), privacy had a greater influence on service experience for the uses public transport group (β = 0.654).

Figure 14.

The public transport moderator influenced one regression path.

For those who frequently use public transportation, privacy emerges as a more prominent concern in their evaluation of the service experience offered by PR services. This indicates that to enhance the service experience and increase acceptance of PR among public transport users, it is important that PR providers prioritize addressing privacy concerns. These findings highlight the need for careful attention to privacy-related aspects of the service experience in order to appeal to public transportation users who are likely to have more experience with shared transportation settings.

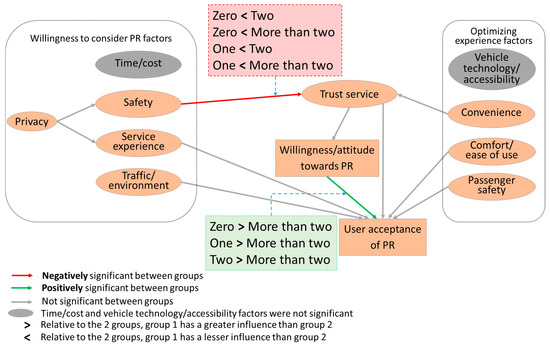

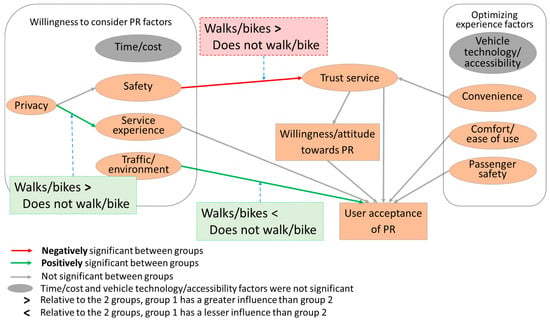

3.12.3. Walk/Bike

The walk/bike moderator consisted of two groups: (1) walks/bikes and (2) does not walk/bike. Table 15 shows the regression paths that were significantly different from the unconstrained model. The privacy → service experience (∆χ2 = 6.292, p < 0.05), safety → trust service (∆χ2 = 8.358, p < 0.01), and traffic/environment → user acceptance of PR (∆χ2 = 6.905, p < 0.01) regression paths were significantly different from the unconstrained model, indicating the moderator, walk/bike, influenced these three paths.

Table 15.

Multigroup analysis of walk/bike highlighting significant paths.

Next, the group differences using model comparison were obtained for the significant regression paths; see Figure 15. In comparison to the does not walk/bike group (β = 0.486), privacy had a greater influence on service experience for the walks/bikes group (β = 0.573). Safety had a greater negative influence on trust service for the walks/bikes group (β = −0.789) compared to the does not walk/bike group (β = −0.571). In comparison to the walks/bikes group (β = 0.015), traffic/environment had a greater influence on user acceptance of PR for the does not walk/bike group (β = 0.106).

Figure 15.

The walk/bike moderator influenced three regression paths.

For individuals who typically utilize walking or biking as their mode of transportation, privacy plays a crucial role in influencing their service experience with PR services. In other words, the walk/bike user group maintains a higher emphasis on privacy. Moreover, these users also demonstrate heightened sensitivity to safety concerns as it highly influences their trust in PR services in a more substantial manner than for those who do not regularly walk or bike. Those who do not walk or bike are found to give higher importance to traffic and environmental factors when considering the acceptance of PR. This group’s decision to use PR services is more influenced by these factors as compared to individuals who regularly walk or bike. This divergence in influential factors between the two groups highlights how different transport habits can lead to varying priorities and considerations when it comes to adopting PR services.

3.12.4. Telecommute

The telecommute moderator consisted of two groups: (1) used telecommute and (2) does not use telecommute. The chi-square model comparison showed no significant difference between the unconstrained model and when the 11 regression paths were constrained individually.

This finding suggests that the adoption and acceptance of PR services were relatively consistent between those who do and do not telecommute, with similar relationships held across these two distinct groups.

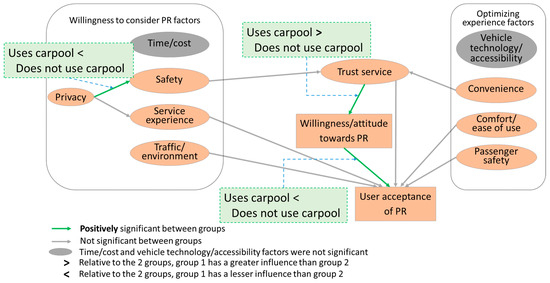

3.12.5. Carpool

The carpool moderator consisted of two groups: (1) uses carpool and (2) does not use carpool. Table 16 shows the regression paths that were significantly different from the unconstrained model. The privacy → safety (∆χ2 = 12.349, p < 0.001), trust service → willingness/attitude towards PR (∆χ2 = 6.401, p < 0.05), and willingness/attitude towards PR → user acceptance of PR (∆χ2 = 4.648, p < 0.05) regression paths were significantly different from the unconstrained model, indicating the moderator, carpool, influenced these three paths.

Table 16.

Multigroup analysis of carpool highlighting significant paths.

Next, the group differences using model comparison were obtained for the significant regression paths; see Figure 16. In comparison to the does not use carpool group (β = 0.951), privacy had a lesser influence on safety for the uses carpool group (β = 0.881). In comparison to the does not use carpool group (β = 0.594), trust service had a greater influence on willingness/attitude towards PR for the uses carpool group (β = 0.662). In comparison to the does not use carpool group (β = 0.361), willingness/attitude towards PR had a lesser influence on user acceptance of PR for the uses carpool group (β = 0.288).

Figure 16.

The carpool moderator influenced three regression paths.

The influence of certain factors on perceptions and attitudes towards PR services was found to differ between individuals who currently use carpooling and those who do not. Specifically, among individuals who do not use carpooling, privacy was a more substantial factor influencing their safety evaluations compared to those who do use carpooling. This suggests that addressing privacy concerns is a crucial strategy for attracting non-carpool groups to PR services. On the other hand, for carpool users, trust in the service held greater importance on their willingness and attitudes towards PR than it did for non-carpool users, emphasizing the need to build and maintain trust to retain these users. The relationship between willingness and attitudes towards PR and user acceptance of PR was more influential for non-carpool users, with a significant positive influence. This finding shows the importance of effectively promoting the benefits of PR to potential non-carpool users to positively influence their acceptance of PR services.

4. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

4.1. Conclusions

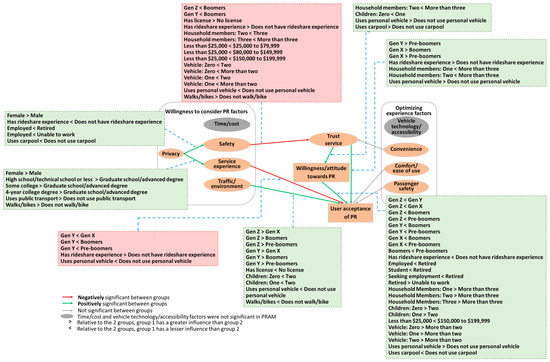

The analysis of our survey data on pooled rideshare (PR) research from a national sample of 5385 individuals began by completing two factor analyses to determine which factors influence users’ decision-making process regarding PR usage. With these factors identified, we developed the Pooled Rideshare Acceptance Model (PRAM), which integrates the factors into a comprehensive framework. The purpose of this exploratory study was to conduct a moderator analysis to explore how different user groups may influence and interact with the identified factors and acceptance of PR, resulting in the Pooled Rideshare Acceptance Model Multigroup Analyses (PRAMMA). This methodical approach allowed us to systematically assess and interpret the complex relationships between user characteristics and their willingness to use PR, ultimately providing a deeper understanding of the factors that drive or deter PR usage. Figure 17 provides a summary of PRAM and PRAMMA.

Figure 17.

Overall summary of the Pooled Rideshare Acceptance Model (PRAM) and Pooled Rideshare Acceptance Model Multigroup Analysis (PRAMMA).

The previous literature [40] presents the development of the Pooled Rideshare Acceptance Model (PRAM), aimed at understanding the barriers and preferences for PR services among a sample of US participants. The PRAM builds upon two independent factor analyses, namely the willingness to consider PR (including time/cost, privacy, safety, service experience, and traffic/environment) and optimizing the PR experience factors (comprising vehicle technology/accessibility, convenience, comfort/ease of use, and passenger safety) [41,42]. It is important to note that the time and cost variables were thoroughly analyzed in the factor analysis and the development of PRAM [40,41,42]. In the PRAM, the time and cost variables did not directly influence the acceptance of PR; therefore, time and cost are not directly evaluated in PRAMMA. Based on PRAM, the purpose of this study was to analyze the strength of the relationships between variables in the PRAM when moderated by 16 demographic variables individually. The multigroup moderation analyses showed the statistical significance between groups for a given moderator in PRAM. The conclusion of this study provides several insights into various significant moderators in the PRAM, such as gender, generation, driver license, rideshare experience, school completion, employment status, number of people in the household, number of children, household annual income, number of vehicles, and typical transport to commute. The 16 individual multigroup analyses explored if it will be beneficial to address the unique concerns or preferences of different user groups, compared to a “one size fits all” approach, which has been used in PRAM analyses. Rather, addressing the distinct needs of different groups may significantly enhance the acceptance and use of PR services.

In the Pooled Rideshare Acceptance Model Multigroup Analysis (PRAMMA), moderators were largely influential in user acceptance of PR, trust in service, and the safety of PR. Safety emerged as a crucial factor, which significantly varied its influence on the trust service for eight moderators; see Table 3. Interestingly, the convenience, comfort, and passenger safety as predictors were not influenced by the moderators, which suggested that these predictors hold importance across all demographic variables.

Gender emerged as a significant moderator, especially with regard to privacy’s influence on safety and service experience. Female participants were found to place a higher emphasis on privacy, highlighting the importance of gender-based privacy considerations in service provision. For different generations, unique strategies tailored to their priorities will be more effective, given their differing safety concerns, service experience preferences, and environmental impact considerations.