4.3. Reliability and Validity Analysis

We performed reliability analysis to evaluate the instrument items to test the potential disruptive variables. Based on the conventional guideline, a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient beyond 0.7 is typically regarded as satisfactory, surpassing 0.8 is preferable, and surpassing 0.9 is ideal for assessing the reliability of an instrument. Following these guidelines,

Table 3 demonstrates that all variables exhibit a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient surpassing the threshold, widely acknowledged as indicative of strong internal consistency. In addition, it is worth noting that the instrument has a commendable level of reliability, surpassing the threshold, indicating highly favorable results.

Discriminant validity is the degree to which study constructs vary among each other [

59]. Similarly, Hair and colleagues defined discriminant validity as the degree to which a study measure varies from another measure in an empirical model [

60]. The discriminant validity is measured through the generally accepted method introduced by the Fornell–Larcker criterion for the present study [

61]. This approach links the square root of Average Variance Explained (AVE) numerical values with each latent variable’s correlational values. For discriminant validity, it is essential to note that all the diagonal and off-diagonal values are less than 0.90. The values of the diagonals are greater than those of other values in the rows.

Table 4 clearly shows that all values fall under the threshold limit. Hence, the instrument has established discriminant validity.

According to

Table 5, a two-tailed test at a significance level of 0.01 indicates that the correlation is statistically significant, and the same is observed at a significance level of 0.05. The correlation matrix should range from 0 to 1, with

p-values of 0.01 and 0.05 being significant. A correlation coefficient of 1 indicates an influential association between the independent and dependent variables, while a 0 indicates no association between the variables. As the table above shows, all variables display a highly significant correlation at the 1% significance level.

4.8. Discussion on Findings

The first hypothesis proposed a positive relationship between an EC and EGB in light of SCT. Accordingly, we found a positive and significant connection (B = 0.435, t = 10.64), inferring that climate dictates behavior. Our results are consistent with prior research, such as the work of Usman and fellows, wherein it was established that the organizational climate derives sustainable behaviors such as participation in environmental campaigns [

29]. Further, our results support Weber and Opoku-Dakwa because they proposed that an ethical climate promotes justice and commitment at the workplace, which urges employees to reciprocate with pro-environmental behaviors [

19]. This proposition is also traceable from the work of Marquardt and colleagues, wherein it was found that organizational priorities toward ethical concerns are reflected in employees’ reciprocated actions [

23]. These findings are also consistent with SCT because they prove that employee behaviors are driven by norms that an organization promotes. An ethical climate promotes a flexible culture wherein trust nourishes and binds individual and organizational goals. Accordingly, the research of Farooq and companions also pointed out that employees’ perception of ethical treatment encourages them to raise their concerns about sustainable practices, which is consistent with our claim [

30]. It implies how social capital covered in an ethical climate fosters cooperation and provokes green behaviors. In addition, employees exhibit green behaviors in three forms: taking pro-environmental initiatives, avoiding environmental harm, and influencing others to behave pro-environmentally. In conclusion, our findings extend the existing literature by documenting evidence that an ethical climate mobilizes employees’ sustainable behaviors.

Likewise, the second hypothesis (H2a) sheds light on EC-driven MOS supported by SCT. The structural model results were significant and positive (B = 0.426, t = 13.626). Based on these findings, we propose that climate strongly connects with employee psychology. When workers experience an EC, they feel a sense of fair treatment, which cultivates the aspiration to behave ethically. The more supportive culture nourishes, the greater the likelihood of ethical behaviors. These findings are aligned with prior literature, such as the research of Li and his fellow, who proposed that a supportive environment influences psychological health, leaving evidence of the effect of climate on workers’ cognition [

38]. In essence, motivation is workers’ effort to achieve a particular task, which is more likely to be prevalent in a psychologically safe culture [

31]. This connection is well explained by Patwary and fellows, clarifying that motivation reflects a desire to achieve and avoid failure [

34]. Connecting these dots, it is proposed that an ethical climate mitigates fear and boosts confidence, which motivates employees to raise efforts. SCT also supports these findings, as an EC enriches the culture of trust, cooperation, and shared values, which protects employees’ well-being. In essence, such a capital embedded in EC aligns the efforts of the organization and employees, promoting motivational force [

37]. Our findings support the hypothesis that an EC fosters MOSs and adds value to SCT by proposing that EC nourishes trust and shares norms that help employees believe in their capacity to raise their effort to achieve desired tasks.

The hypothesis coded by H2b proposed a direct connection between MOS and EGB. According to this, motivated employees are more likely to engage in green behaviors. Our findings also supported a significant positive relationship (B = 0.472, t = 7.499). These findings are also confirmed by SCT, which posits that employee pro-environmental behaviors are the outcome of trust driven by motivation. This proposition is also confirmed by Peker’s research, which emphasized motivation as a strong channel to encourage behaviors [

39]. Further, the outcome of the research of Li and his team also strengthens our stance, as they provided that intrinsic or extrinsic motivation modifies human behavior [

41]. Similarly, Zacher’s work also pointed out that motivational states are higher in those who exhibit pro-sustainable behaviors [

40]. The conclusion of Siyal and fellows also supports our claims, as they pointed out motivation encourages employees to share innovative ideas and participate in environment-related activities voluntarily [

42]. Connecting these insights with our findings leads us to conclude that motivation is the driving force to encourage pro-environmental green behaviors.

The hypothesis coded by H3 seeks to explain the indirect effect of EC on EGB through MOS. According to the mediation analysis results (

Figure 3), we found that MOS significantly mediates the relationship. SCT supports these findings, as motivation plays a central role in translating ethical initiatives to employee behaviors. Further, these findings are consistent with expectations derived from the literature. According to our findings, an EC is similar to social capital in promoting shared norms, integrity, trust, and mutual respect. A similar proposition is made by prior research, claiming that when employees experience such an environment, they feel valued by the employer [

45]. This feeling is further described by Bamberg and Verkuyten; according to them, when employees feel supported by their employer, they exhibit more responsible behavior filled with greater energy [

46]. Similarly, Norton’s stance that employer paybacks induce fair treatment regarding increased commitment is close to our findings [

28]. Connecting the dots from the literature, such as climate, energy, and commitments, and framing them all in our context, we establish that motivation is fundamental in translating the effect of an ethical climate on employees’ green behavior.

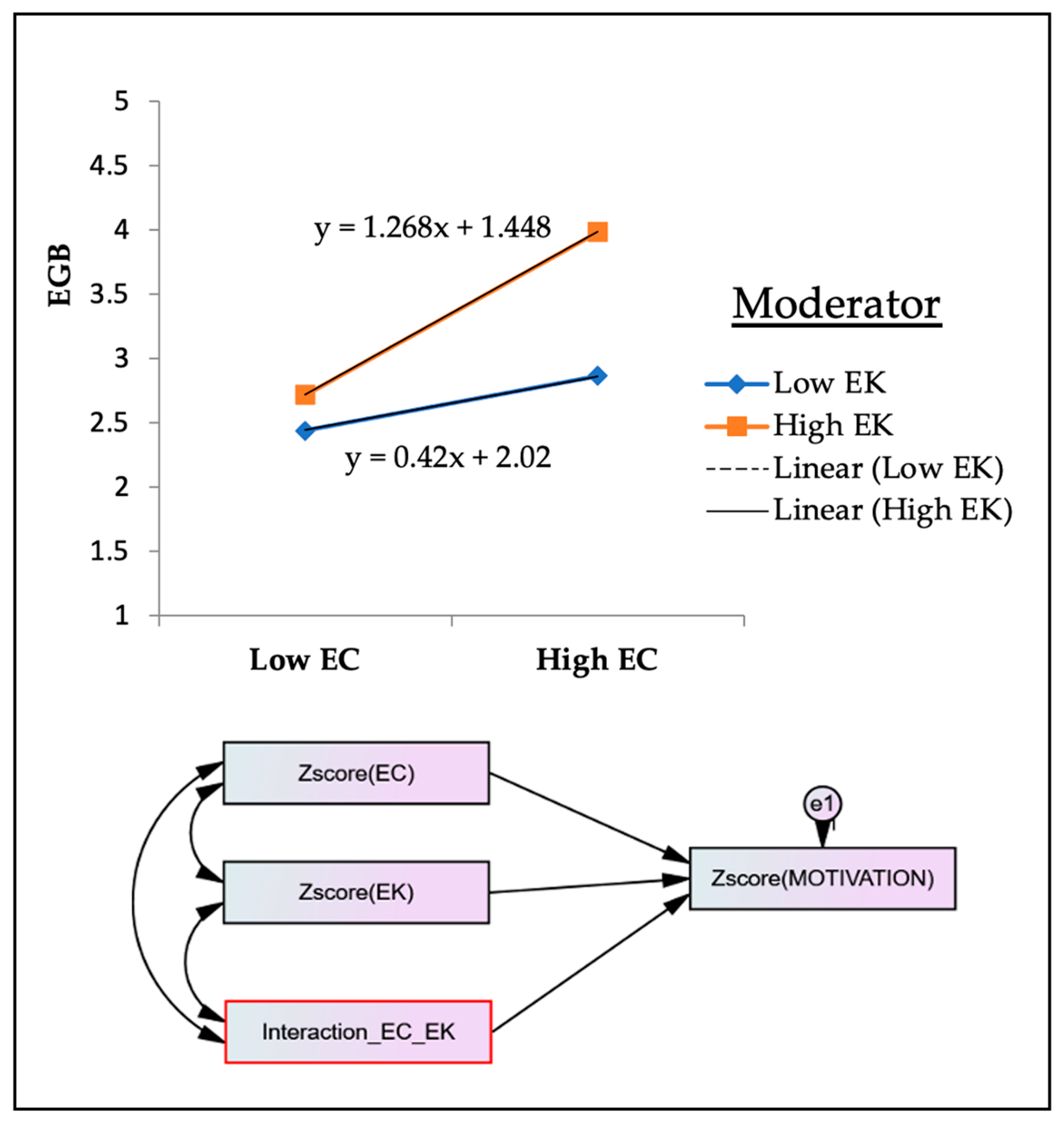

The last hypothesis (H4) proposes that EK significantly moderates the relationship between an EC and MOS. Our findings revealed a significant and positive moderation under the theoretical support of SCT. According to theory, trust, shared norms, and integrity promoted within a climate dictate the behaviors of the underlying workforce. According to Hamzah and Tanwir [

47], although an EC cultivates motivation, its true reflection is determined by employees’ level of environmental knowledge. Those organizations where the EC is strong but whose employees lack EK fail to motivate their workforce towards sustainable goals. Ideas of the necessity of knowledge further demonstrated that employees face behavioral challenges due to limited knowledge particularly related to the environment [

49]. In essence, EK makes employees better positioned to understand values and norms prevailing under the ethical climate, which enhances their confidence and readiness to act ethically. Hence, employees with greater EK tend to engage in pro-environmental behaviors more than those who lack in this area [

15]. Furthermore, Raza and Khan support this idea through demonstrating that trust in ethical initiatives is built on the basis of the level of ethical knowledge [

48]. Trust is central to SCT, which connects sustainable efforts with employee motivation, and this connection is stronger where EK is higher. Thus, based on our findings and support from the literature, organizational efforts to promote an ethical climate are better reflected in employee motivation when they possess greater EK.

4.8.1. Theoretical Implications

This work possesses various theoretical implications. The initial topic pertains to the literature on ethical climates, specifically emphasizing the consequences of non-environmentally friendly behavior. Nevertheless, the present study offers a comprehensive and analytical perspective on the impact of climates on EGB, a topic that has not yet been thoroughly investigated in previous research. Based on the research findings, it can be concluded that an EC has a considerable and positive influence on EGB. The observed association aligns with the SCT as proposed by Bandura. Furthermore, EK has been found to enhance employee motivation within the organizational setting, hence positively impacting the overall quality of life experienced by employees. This helps enhance environmentally conscious behavior among employees. Furthermore, our research addresses a pertinent issue raised by investigating the impact of an EC on the behavioral outcomes of followers within the organizational setting. In addition, our research uncovered the presence of a mediating mechanism, specifically the role of motivational states, in the relationship between an EC and EGB, by augmenting our comprehension of the mechanisms that underlie this organizational environment. In this study, EK was recognized as a significant determinant of the impact of EC on the empowerment of employees and the promotion of environmentally sustainable practices. This finding demonstrates that the presence of EK in an organization has a moderating effect on the ethical atmosphere, leading to an increased employee motivational state, ultimately resulting in enhanced employee job performance.

4.8.2. Practical Implications

Contemporary organizations can promote green behaviors by providing a supportive climate. Indeed, it will enhance transparency and fairness followed by sustainability. In essence, employees require fair treatment and trust, which is essential to transform effort into anticipated outcomes. Organizations may foster pro-environmental programs such as renewable resources, reductions in carbon footprints, and waste management. MOSs play the basic role in translating ethical initiative into individual ethical behavior. For this, hotel management either requires mandatory initiatives or encourages voluntary behavior. For instance, mandatory behaviors include ethical training or assignment of ethical activities, while voluntary behavior includes a reduction in paper usage by employees, participation in environmental campaigns, and sharing innovative ideas. For voluntary behaviors, organizations need to encourage them, which is possible through providing a supportive environment. Besides motivation, hotel managers are required to have sufficient knowledge about environmental concepts because it could either trigger green behavior or limit significantly. Thus, our findings serve as the guiding tool to manage EC-driven green behavior, particularly in the accommodation sector.

Organizations should consider implementing employee mentoring schemes in order to attain performance objectives and foster a climate of open communication inside the organization. When engaging in the promotion of current employees and the recruitment of new personnel, managers should inquire about the past environmental performance of the individuals in question. It is recommended that selection and promotion committees incorporate the candidate’s environmental assessment as part of their evaluation process. Moreover, the results of this study carry significant implications for society. It garners public interest towards the socially responsible and environmentally conscious endeavors undertaken by individuals and entities. It also helps organizational leaders in demonstrating environmentally conscious behavior. In essence, this research study elucidates the significance of individual members of society engaging in environmentally friendly behavior as a means of safeguarding the natural environment.