6.1. Experiment Design, Participants, and Procedure

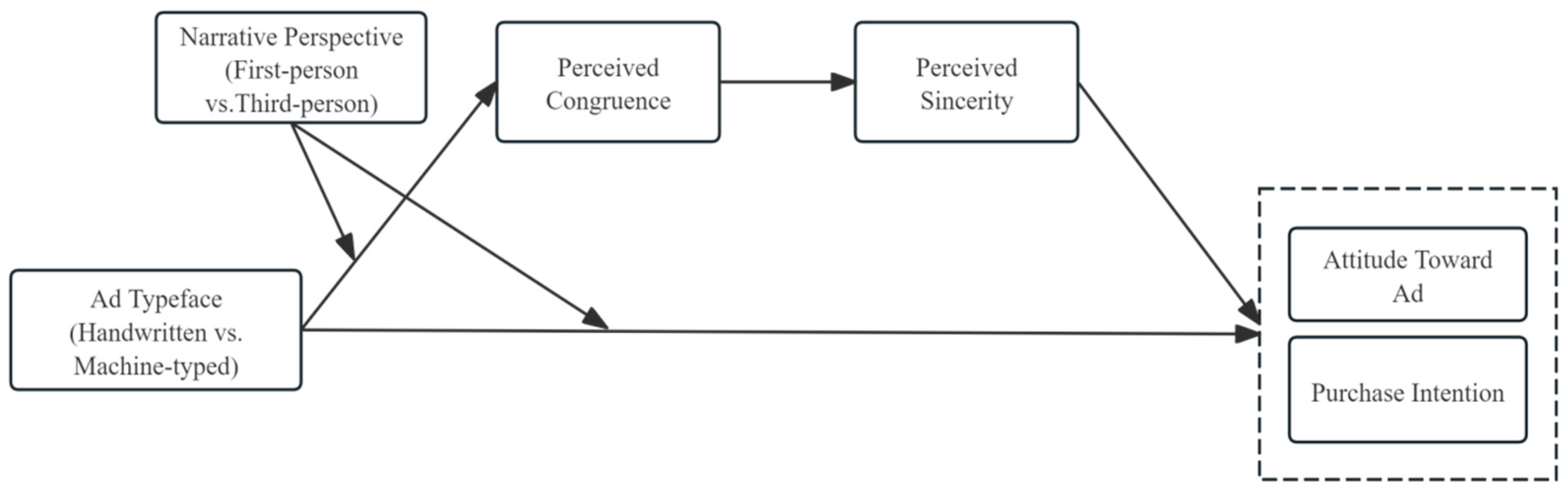

To examine the mediating effect and moderating effect, a 2 (typeface: handwritten vs. machine-typed) × 2 (narrative perspective: first-person vs. third-person) between-subject experimental design was adopted to verify the hypotheses.

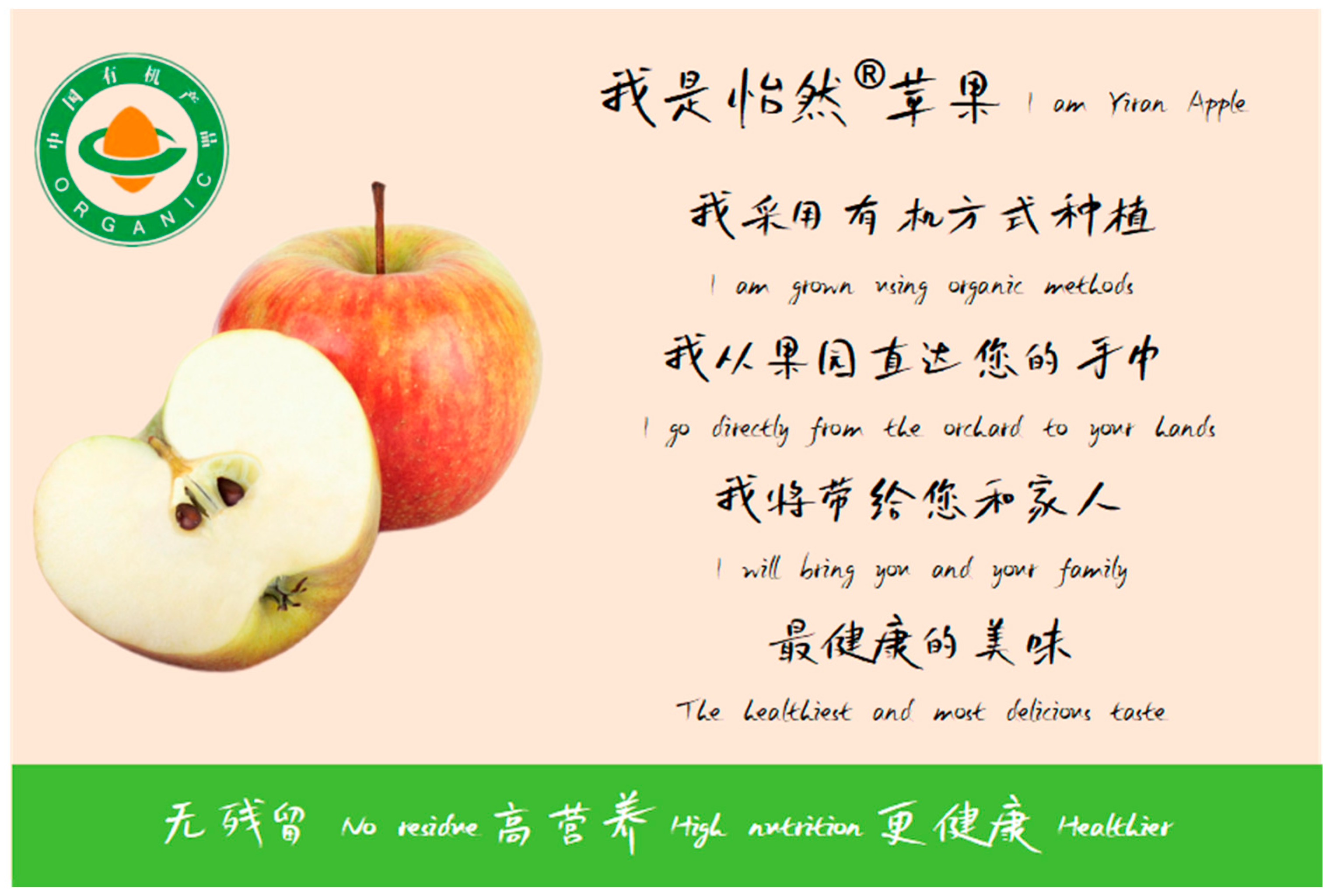

The experimental stimuli consisted of advertisements for organic food. Study 2 used an organic apple instead of a tomato to avoid material repetition and enhance external validity. Both were common, natural products in the organic food category. The ad layout, message length, and core manipulations (typeface and narrative) remained consistent throughout studies.

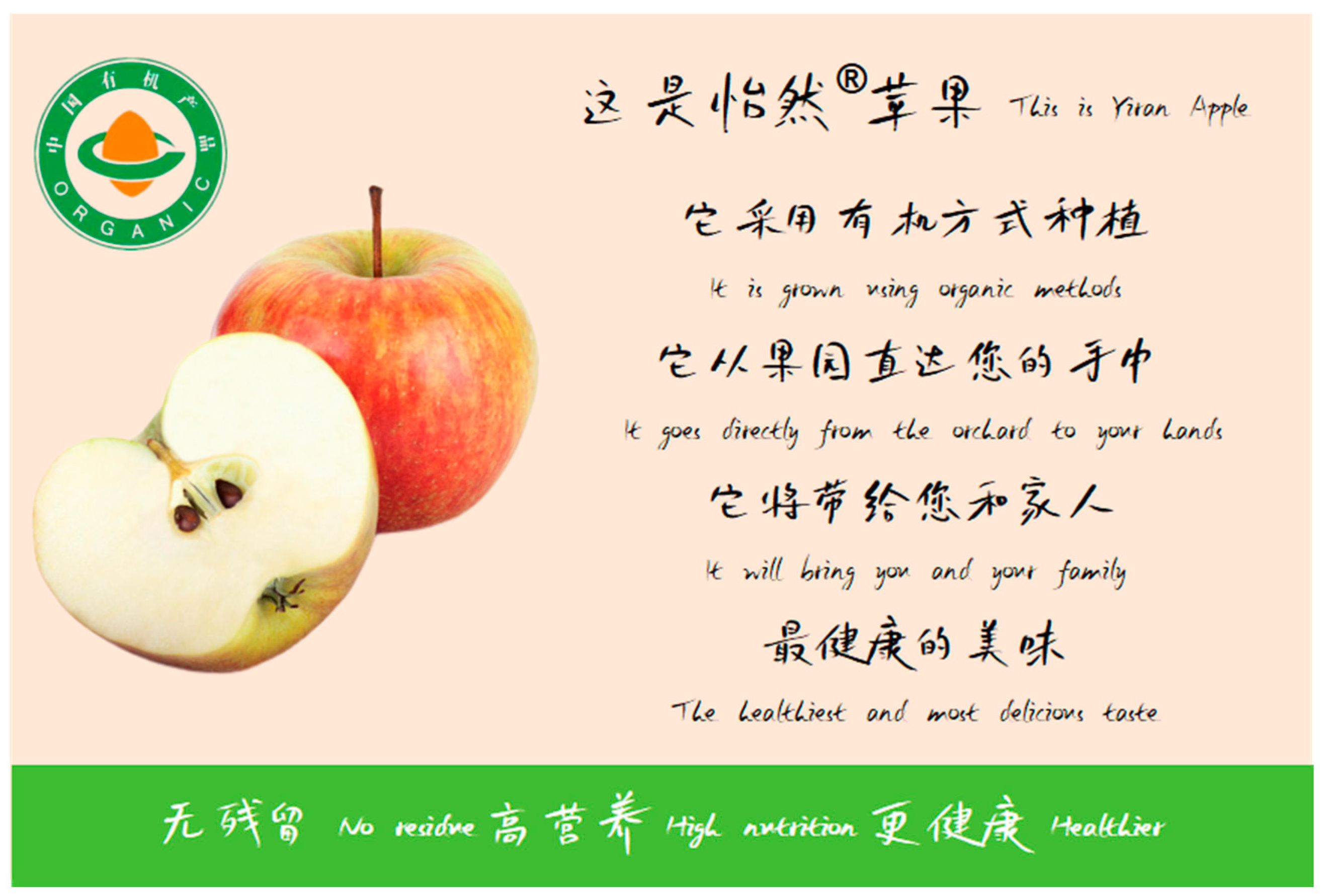

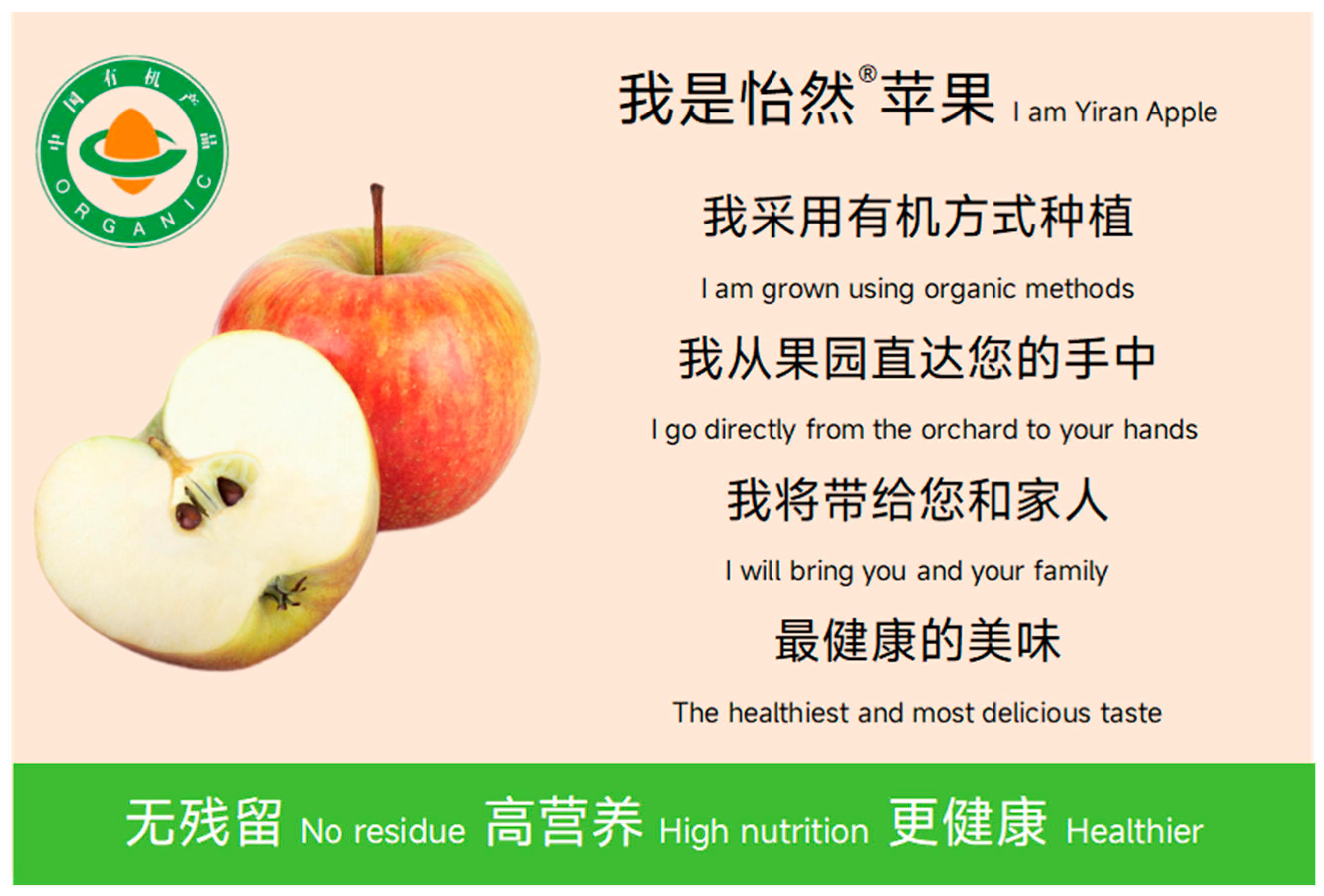

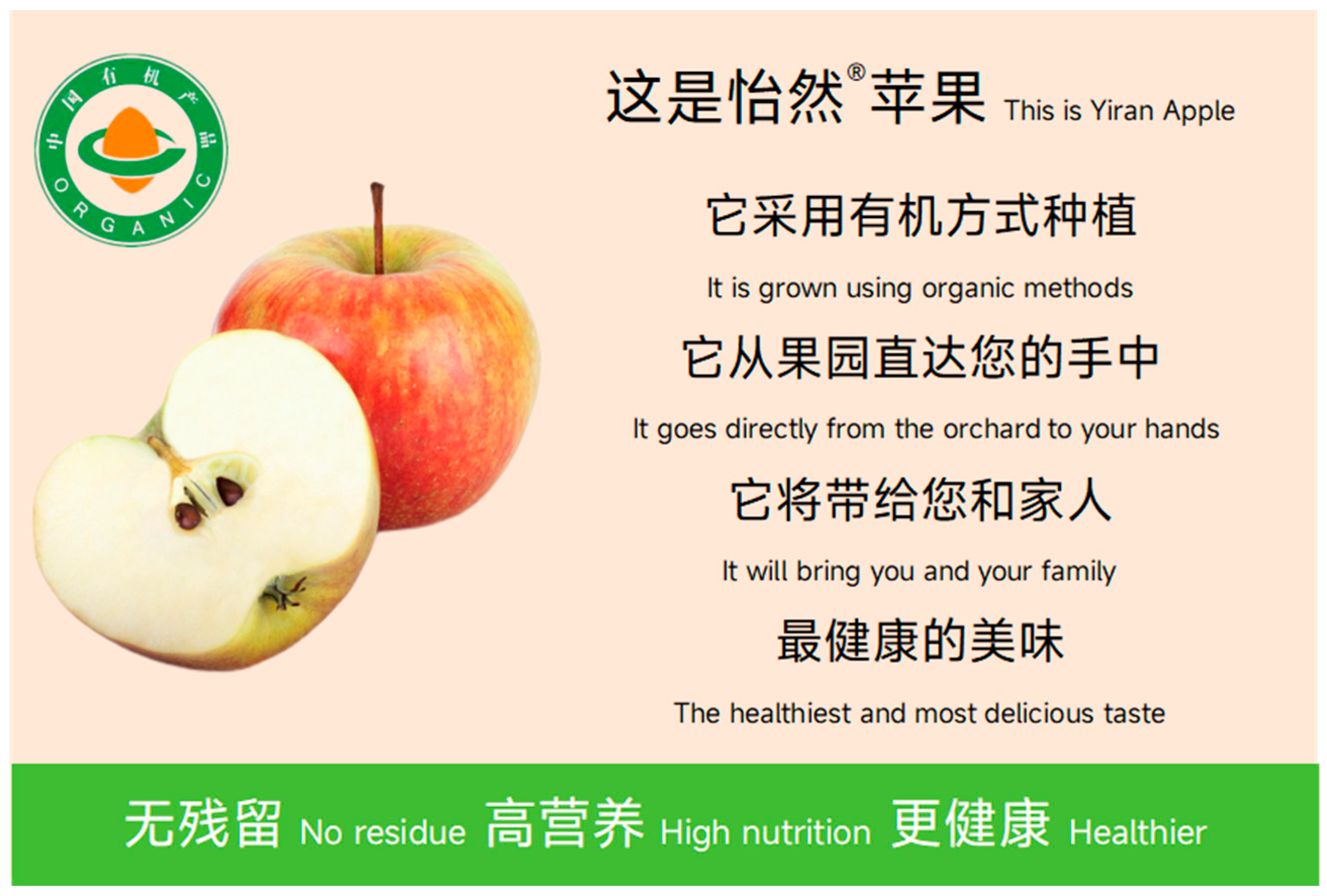

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four condition groups. They were required to imagine that when browsing the web, they saw an advertisement. The ad featured the “Yiran” organic apple, a product that belongs to the organic food category and is used to promote the concept of healthy eating. In addition to the apple, there was a short advertising content illustrating the product. The ad typeface was manipulated through two stimuli tested before, Hongleizhuoti (handwritten) and Misans (machine-typed), respectively. Narrative perspective was manipulated through different pronouns (first-person: I vs. third-person: It). For example, the first-person narration text was “I am Yiran Apple. I am grown using organic methods. I go directly from the orchard to your hands. I will bring you and your family the healthiest and most delicious taste”. The third-person perspective content was “It is Yiran Apple. It is grown using organic methods. It goes directly from the orchard to your hands. It will bring you and your family the healthiest and most delicious taste”. The two typeface and two narratives perspectives comprised the four experimental conditions used in this study as stimuli (

Appendix C).

After reading these materials, participants completed a series of questions measuring their perceived congruence [

19] from one (totally disagree) to seven (totally agree) (α = 0.90). Their perceived sincerity was measured by a four-item seven-point scale [

61,

69] (α = 0.89). Their attitude toward the ad was measured by three items [

70] (α = 0.91). Finally, the purchase intention scale consisted of three items [

70] (α = 0.92). The measurement scales are provided in

Table 6.

To conduct the manipulation check of typeface, participants were required to assess one item: “The typeface of ads appears to be handwritten” [

16,

37]. Moreover, participants were asked to respond to one item: “The content is narrated in the first person”. To check the scenario realism of ads, participants were asked to respond to the following item: “In real life, advertisements for such products may appear”. (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) [

37].

To estimate the minimum required sample size, G*Power was used. Using a configuration of effect size f of 0.25, a power of 0.80, a significance of 0.05, and 4 groups, the calculated minimum sample should be 180 cases. A total of 228 undergraduate students from a Chinese university were invited to participate in this experiment in exchange for course credit. To maintain the validity of the sample, any participants who failed the manipulation check or completed the questionnaire in an unrealistically short time were excluded.

The final sample size was composed of 206 valid cases. Among the participants, 72.3% were female and over 94.7% were aged between 18 and 25. As participants were randomly assigned into one of four conditions, gender showed no significant differences under conditions (handwritten condition—74% female; machine-typed condition—70.6% female; χ2 (1, N = 206) = 0.306, p = 0.58, confirming the success of randomization.

In addition, participants’ prior purchase experience with organic food and their trust in organic food brands were also measured, as prior studies suggest these variables may influence consumers’ responses to organic advertising [

17,

42]. Although not included in the main analysis, these variables were added as covariates in supplementary robustness checks, the results of which are reported in

Appendix D.

6.2. Data Analysis and Result

Confirmatory factor analysis: Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using AMOS 26.0 to evaluate the construct validity of the measurement model. The results demonstrated a good model fit: χ2/df = 1.917, CFI = 0.969, TLI = 0.961, RMSEA = 0.067, and GFI = 0.905. All the indicators had a good fit criterion. Therefore, the construct validity of the model was well-supported.

Specifically, the factor loadings ranged from 0.708 to 0.937, all exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.5, indicating the adequate convergent validity of the items. A detailed list of items and their corresponding loadings is provided in

Table 6. To evaluate internal consistency, composite reliability (CR) values were calculated, ranging from 0.89 to 0.93, all above the acceptable cutoff of 0.7 (

Table 6). Furthermore, the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct ranged from 0.64 to 0.81, surpassing the minimum threshold of 0.5. Discriminant validity was also supported, as each construct’s AVE exceeded the squared correlations with other constructs [

71].

Manipulation checks: A manipulation check was conducted to test the differences between typefaces. It showed that participants’ perceptions differed significantly between conditions (Mhand = 5.65, SD = 1.29, vs. Mmachine = 2.20, SD = 1.20, t (204) = 19.89, p < 0.001, d = 2.77). Moreover, their perception of narrative perspective also presented significantly different (Mfirst = 6.31, SD = 0.94, vs. Mthird = 1.92, SD = 1.21, t (204) = 29.19, p < 0.001, d = 4.07). The realism of the scenario was also tested, and the result showed that people believed that this kind of ad would appear in real life (M = 5.79, SD = 0.92) and the result of the realism scenario indicated that there no significant differences between typeface conditions (M = 5.78 and M = 5.79, respectively; F (1, 204) = 0.014, p = 0.91).

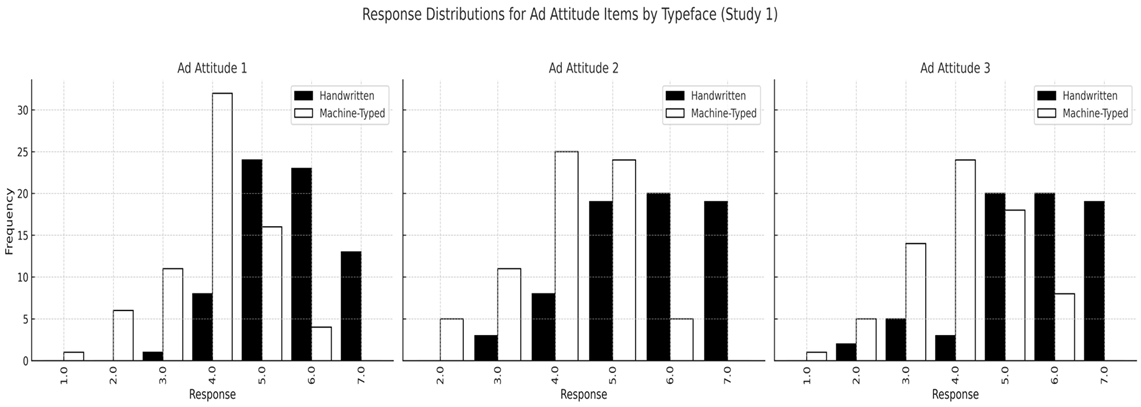

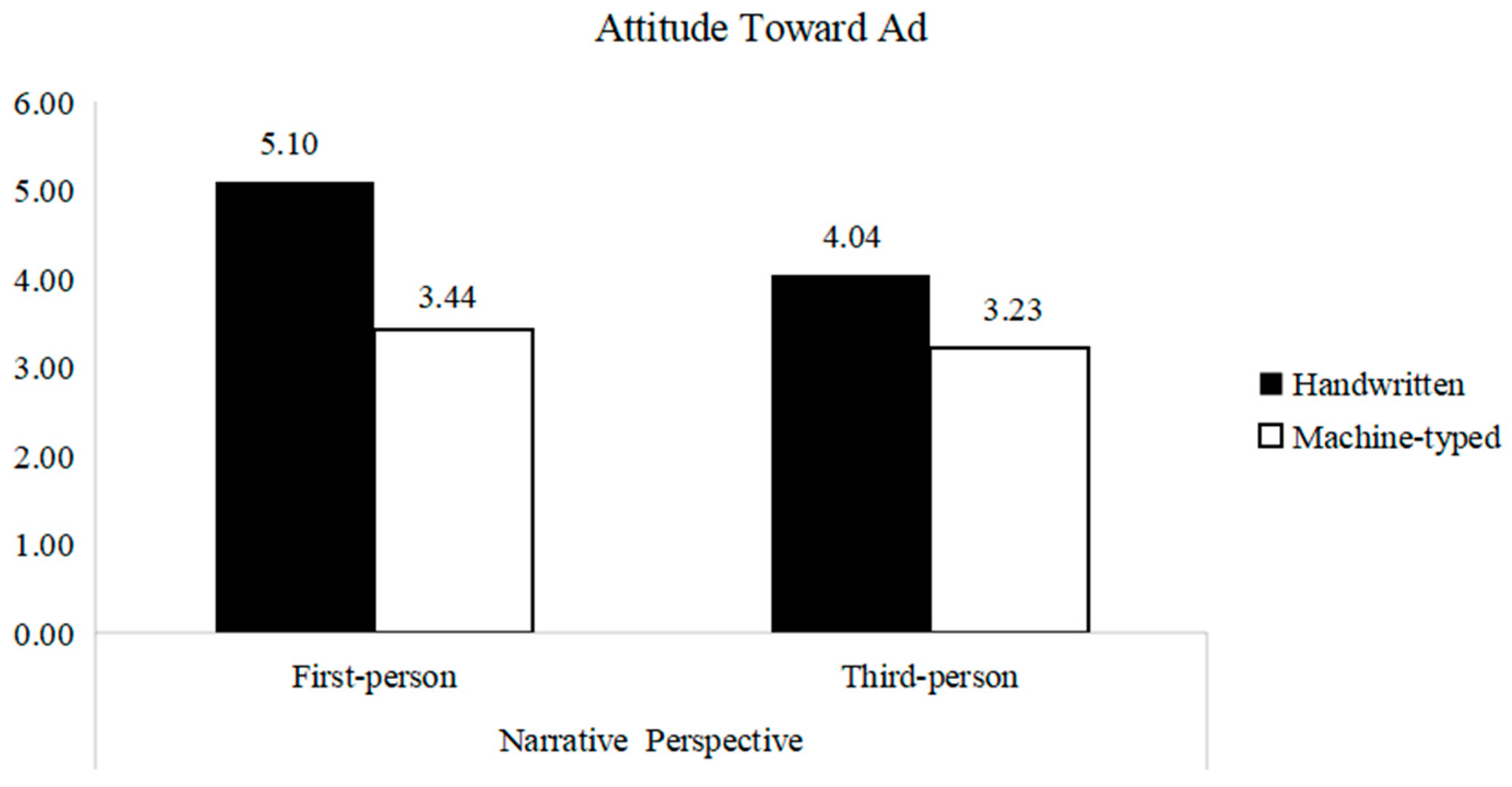

Consumer response: attitude towards ads. Two-way ANOVA was conducted to test the result of attitudes toward ads. The main effect of typeface on attitude toward ads was significant (

F (1, 202) = 45.02,

p < 0.001,

η2 = 0.182), and there was a significant effect of narrative on attitude toward ads (

F (1, 202) = 12.03,

p < 0.001,

η2 = 0.056). Moreover, their interaction effect was also significant (

F (1, 202) = 5.28,

p < 0.05,

η2 = 0.025). More specifically, when ad narration was first-person, handwritten typeface (M = 5.10, SD = 1.18) engendered significantly more favorable attitudes than machine-typed variants (M = 3.44, SD = 1.47,

F (1, 103) = 40.74,

p < 0.001). When ad narration was third-person, handwritten typeface (M = 4.04, SD = 1.29) also triggered more positive attitudes than machine variants (M = 3.23, SD = 1.33,

F (1, 99) = 9.71,

p < 0.01) (see

Figure 2).

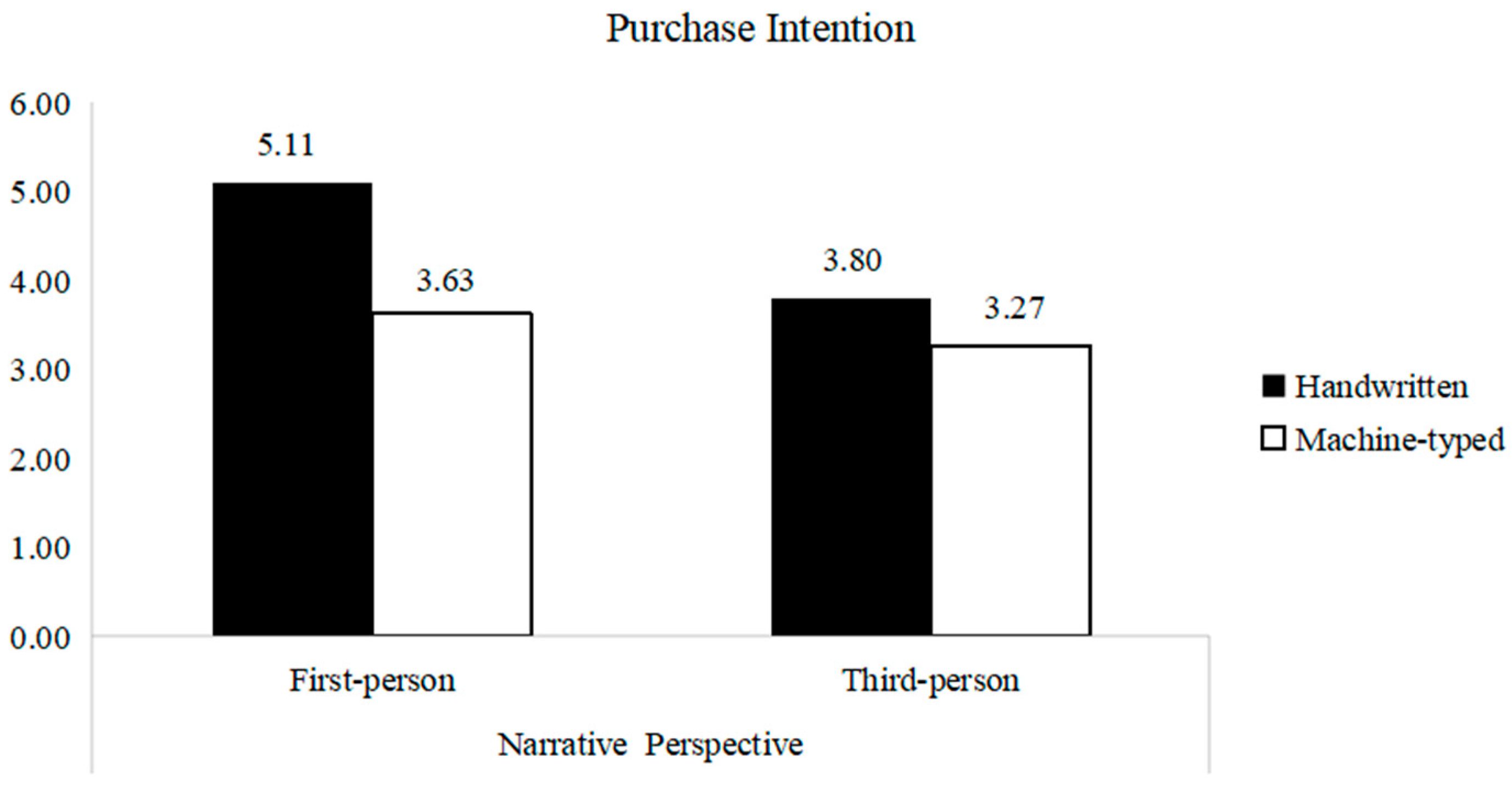

Consumer response: purchase intention. A two-way ANOVA was conducted to test purchase intention. The main effect of the typeface was significant (

F (1, 202) = 26.59,

p < 0.001,

η2 = 0.116), and the main effect of the narrative was also significant (

F (1, 202) = 18.67,

p < 0.001,

η2 = 0.085). More specifically, the interaction effect of typeface x narrative perspectives was significant (

F (1, 202) = 5.92,

p < 0.05,

η2 = 0.025). When the ad adopted first-person narration, the use of handwritten typeface (M = 5.11, SD = 1.33) led to a higher level of purchase intention compared with machine-typed writing (M = 3.63, SD = 1.61,

F (1, 103) = 26.54,

p < 0.001). When ads utilized a third-person perspective, handwritten typeface (M = 3.80, SD = 1.37) also triggered higher purchase intention than machine ones (M = 3.27, SD = 1.27,

F (1, 99) = 4.09,

p < 0.05) (see

Figure 3). These results supported H2.

Moreover, including both covariates (prior experience and brand trust) in the ANCOVA led to the result pattern remaining significant (see

Appendix D).

Moderated mediation analysis: In order to test H3, moderated mediation analysis was run through the bootstrapping method (SPSS, version 27.0. Process Model 86) [

34,

37,

56,

72]. In this test, the typeface was used as the independent variable. We used perceived congruence and perceived sincerity as mediators, employing attitude toward ads and purchase intention as dependent variables, respectively, and using narrative perspective as the moderator. The handwritten typeface was coded as 1 and the machine-typed as 0, while the first-person narrative was coded as 1 and the third-person style was coded as 0.

First, the moderated mediation effect was examined regarding attitudes toward ads. The bootstrapping results showed a significant moderated mediation effect by narrative perspective through perceived congruence and perceived sincerity (index of moderated mediation = 0.1587, 95% CI = [0.0166, 0.3577]). More specifically, the indirect effect was stronger when the narration was first-person (effect = 0.3223, 95% CI = [0.1643, 0.5380]) due to the serial mediation effect of perceived congruence and perceived sincerity when compared to third person (effect = 0.1635, 95% CI = [0.0598, 0.2929]), which confirmed that first-person narration engenders more favorable attitude than third-person narration.

Secondly, the moderated mediation effect was examined on purchase intention. The results showed a significant moderated mediation effect of the narrative perspective (index of moderated mediation = 0.1904, 95% CI = [0.0169, 0.4046]). More specifically, the indirect effect was stronger when the narration was first-person (effect = 0.3865, 95%CI = [0.2019, 0.6092]) through perceived congruence and perceived sincerity, when compared to third-person (effect = 0.1961, 95% CI = [0.0735, 0.3428]), confirming that when utilizing first-person narration, organic product ads would lead to stronger purchase intention than those used third person’s (see

Table 7).

The results certified that when the first-person perspective was used in organic product ads, it engendered a more positive attitude toward ad and purchase intention through perceived congruence and perceived sincerity when compared to third-person narration, supporting H3. This suggested that when both the handwritten typeface and the first-person narrative perspective were used in organic food advertising, they triggered positive consumer responses by enhancing perceptions of congruence and sincerity, which were essential for highlighting the rustic and natural qualities of organic food and boosting the development of organic farming and sustainable food production.