Community Environmental Leadership and Sustainability: Building Knowledge from the Local Level

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Leadership and Sustainability

1.2. Sustainable Development and Community Leadership

1.3. Environmental Education and Leadership Training

1.4. Research Objective

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Area and Context of Study

2.2. Type of Research and Procedure

2.3. Phase 1: Identification of Potential Environmental Leaders

2.4. Phase 2: Diagnosis of Training Needs of Environmental Leaders

2.5. Phase 3: Development of the Program to Strengthen Capacities

- Deontological: The profile of the environmental leader was defined on the predominant leadership characteristics and its evolution, as outlined in Phase 1.

- Epistemological: The knowledge that enabled the identified leaders was built upon the findings of the TDN.

- Pedagogical: A training model based on cognitivism, socio-constructivism, critical pedagogy and a competency-based approach was adopted, ensuring that leaders actively participate in constructing their own knowledge.

- Contextualization: Findings from Phase 1 guided the curriculum design, ensuring relevance to local leadership styles and environmental issues.

- Structuring: Content was aligned with training needs, incorporating the historical, economic, and ecological context [27].

- Programming: Four four-hour training sessions were scheduled at a local public educational facility. Sessions integrated prior knowledge exploration and interactive strategies to address the climate crisis.

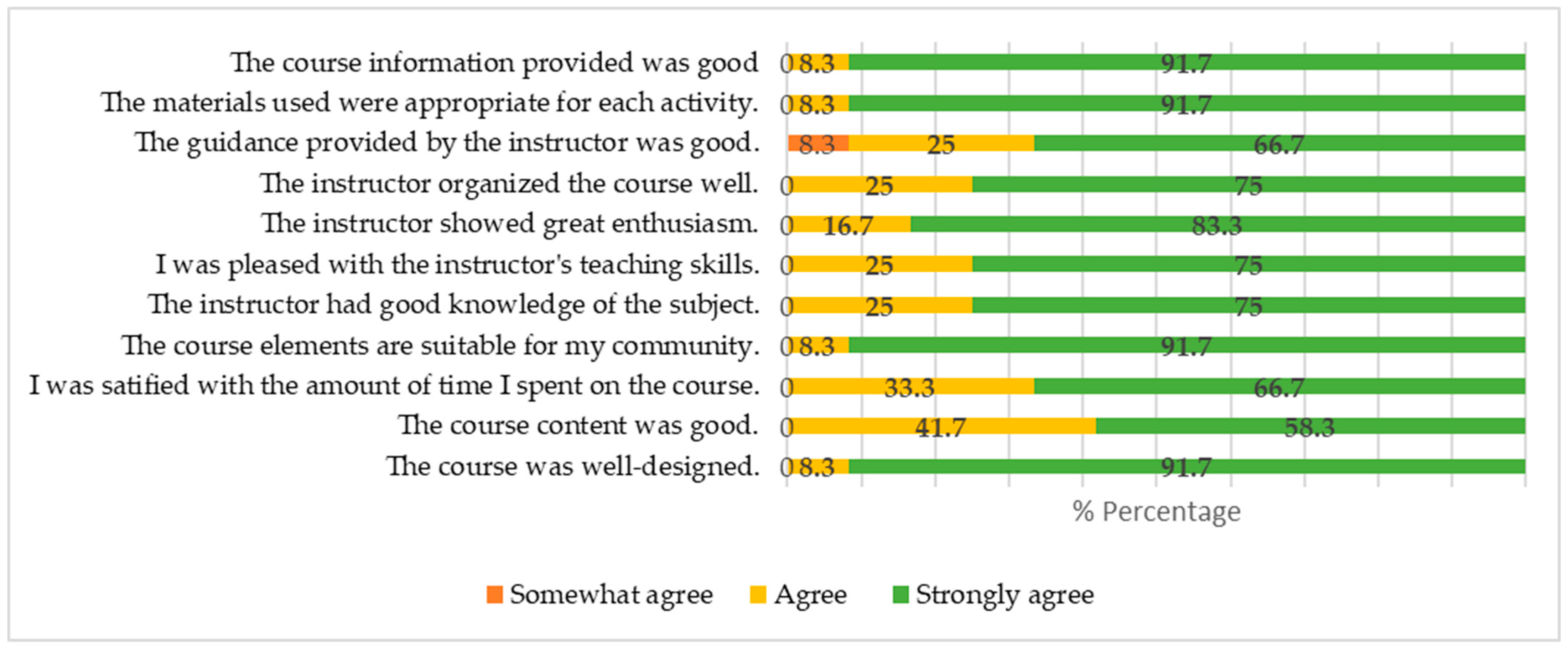

- Evaluation: After program completion, 12 surveys (adapted from Stocking et al. [58] were conducted to assess: relevance of content, facilitator expertise, session duration, material effectiveness, and perceived impact on leadership skills. As mentioned in previous statistical analysis, since the assumption of normality was met for all the samples, a one-sample t-test was conducted to determine whether the sample mean significantly differed from the reference value of 5. Additionally, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to estimate the range within the true population mean is likely to fall, using the formula presented in Equation 1. The data were processed using Minitab statistical software.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of the Environmental Leaders

3.2. Presentation of Environmental Problems in the Communities

3.3. Cleanup Campaign

3.4. Training Needs of Environmental Leaders

3.5. Training Program for the Development of Environmental Competencies

3.5.1. First Session, 27 August 2022

3.5.2. Second Session, 3 September 2022

3.5.3. Third Session, 10 September 2022

3.5.4. Fourth Session, 24 September 2022

3.6. Evaluation of the Environmental Leaders Training Program in the Context of Sustainable Development

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| TDN | Training Needs Diagnosis |

| ESG | Environmental Social Governance |

| GTL | Green Transformational Leadership |

| SMEs | Small–Medium Entrepreneurs |

| ESTL | Environmentally Specific Transformational Leadership |

| UNEP | United Nations Environment Program |

| CONABIO | Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad |

| CONAGUA | Comisión Nacional del Agua |

| CONAPESCA | Comisión Nacional de Pesca y Acuacultura |

| SEMAREN | Secretaria del Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales |

References

- Celis Campos, I. Liderazgo Ambiental: Una Práctica Imprescindible. Saving The Amazon. 13 May 2021. Available online: https://savingtheamazon.org/blogs/news/liderazgo-ambiental-una-practica-imprescindible (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Chávez, J.; Ibarra, M. Liderazgo y cambio cultural en la organización para la sustentabilidad. TELOS Rev. Estud. Interdiscip. Cienc. Soc. 2016, 18, 138–158. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, G.; Hernández, O.; González, F. Liderazgo comunitario y su influencia en la sociedad como mejora del entorno rural. Rev. Innova ITFIP 2019, 5, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes-Duarte, R.; Santos-Echeandia, J.; Rodríguez-Herrera, J.; Marmolejo-Rodríguez, A. Estudio integral de la calidad del agua en el litoral del puerto San Carlos, Baja California Sur, México. Rev. Int. Contam. Ambient. 2020, 36, 927–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez, L.; Rodríguez, C.; López, J.L.; Salinas, S.; Bello, M. Análisis socioambiental de la Laguna de Tres Palos, México: Un enfoque socioecosistémico. Reg. Cohesión 2023, 13, 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente [PNUMAGEO 6 Perspectivas del medio ambiente mundial]. Resumen para responsables de políticas. 2019, pp. 9–11. Available online: https://www.unep.org/es/resources/perspectivas-del-medio-ambiente-mundial-6 (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Sandoval, A. La problemática detrás del Lago de Chapala. Gac. UNAM 2021. Available online: https://www.gaceta.unam.mx/?s=chapala+ (accessed on 5 February 2022).

- Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales [SEMARNAT]. Informe de la Situación del Medio Ambiente en México, 1st ed.; SEMARNAT: Mexico City, México, 2018; p. 22. Available online: https://apps1.semarnat.gob.mx:8443/dgeia/informe18/tema/pdf/Informe2018GMX_web (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Sumaya, F. Evaluación de la Calidad Ambiental del Humedal Refugio de Vida Silvestre Sistema Lagunar de Tisma, Masaya, Nicaragua; Tesis de Maestría en Ciencias en Manejo y Conservación de los Recursos Naturales Renovable, Facultad de Recursos Naturales y del Ambiente-Universidad Nacional Agraria: Managua, Nicaragua, 2018. Available online: https://apps1.semarnat.gob.mx:8443/dgeia/informe18/tema/pdf/Informe2018GMX_web.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Bolden, D.R.; Gosling, J.; Hawkins, B. Exploring Leadership; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Volume 83, p. 97. [Google Scholar]

- Northouse, P.G. Leadership: Theory and Practice, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Carrera, R.; Bautista-Vallejo, J.M. El Liderazgo en la Educación: Conceptos, Modelos y Estilos en el Marco Actual. In Investigación, Tecnología y Sociedad: Investigación e Innovación en Educación; Dykinson, S.L.: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 2065–2068. [Google Scholar]

- Changar, M.; Atan, T. The Role of Transformational and Transactional Leadership Approaches on Environmental and Ethical Aspects of CSR. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liefferink, D.; Wurzel, R. Environmental leaders and pioneers: Agents of change? J. Eur. Public Policy 2016, 24, 951–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y. Sustainable leadership: A literature review and prospects for future research. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, A.; Walkowiak, K.; Bernaciak, A. Leadership Styles of Rural Leaders in the Context of Sustainable Development Requirements: A Case Study of Commune Mayors in the Greater Poland Province, Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R. The greening of Chicago: Environmental leaders and organisational learning in the transition toward a sustainable metropolitan region. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2010, 53, 1051–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdugo-Araujo, L.M.; Tereso-Ramírez, L.; Carrillo-Montoya, T. La participación comunitaria como vía para el empoderamiento de encargadas del programa Comedores Comunitarios en Culiacán, México. Prospectiva. Rev. Trab. Soc. Interv. Soc. 2019, 28, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Wang, X.; Xiao, H. What motivates environmental leadership behaviour—An empirical analysis in Taiwan. J. Asian Public Policy 2017, 11, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe [CEPAL]. Acerca de Desarrollo Sostenible 2024. Available online: https://www.cepal.org/es/temas/desarrollo-sostenible/acerca-desarrollo-sostenible (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- Novo, M. La educación ambiental, una genuina educación para el desarrollo sostenible. Revista de Educación número extraordinario 2009. pp. 195–217. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3019430 (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- Organización de las Naciones Unidas [ONU]. La Agenda para el Desarrollo Sostenible. 2024. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/development-agenda/ (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Cámara de Diputados del, H. Congreso de la Unión. Ley General de Equilibrio Ecológico y la Protección al Ambiente. Última Reforma Publicada en el Diario Oficial de la Federación 01-04-2024; 6. Available online: https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/LGEEPA.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Ferragut, E.; Velázquez, Y.T.; Pérez, E. Programa de educación ambiental para la comunidad de la Conchita, Pinar del Río. CIGET. Holguín 2018, 20, 308–318. [Google Scholar]

- Tovar-Gálvez, J.C. Hacia una educación ambiental ciudadana contextualizada: Consideraciones teóricas y metodológicas. Desde el trabajo por proyectos. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. 2012, 58, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, L.; Buendía, M. Guía para la Estructuración y Programación de un Proyecto de Educación Ambiental y para la Sustentabilidad; Documento interno de trabajo; Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí: San Luis Potosí, Mexico, 2008; pp. 1–24. Available online: https://www.uv.mx/mie/files/2012/10/SESION10-14-ABRIL-GuiaparalaevaluacionNieto.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Rojas Casarrubias, C.; Rodríguez Alviso, C.; Aparicio López, J.L.; Castro Bello, M.; Villerías Salinas, S.; Bedolla Solano, R. Problemas socioambientales desde la percepción de la comunidad: Pico del Monte-laguna de Chautengo, Guerrero. Soc. Y Ambiente 2023, 26, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D.H. Teorías del Aprendizaje, 6th ed.; Pearson Educación: Guadalajara, México, 2012; pp. 238–246. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/39617127/SEXTA_EDICIÓN_TEORÍAS_DEL_APRENDIZAJE_Una_perspectiva_educativa (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Márquez Duarte, F. Modelo de Naciones Unidas: Una herramienta constructivista. Alteridad 2019, 14, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorliza, K. Environmental leadership, practices and sustainability. Palarch’s J. Archaeol. Egypt/Egyptol. 2020, 17, 4370–4378. [Google Scholar]

- Tovar-Gálvez, J.C. Fundamentos para la formación de líderes ambientales comunitarios: Consideraciones sociológicas, deontológicas, epistemológicas, pedagógicas y didácticas. Rev. Luna Azul 2012, 34, 214–239. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, B.; Paz, R.; Chapalbay, R. Escuela de liderazgo ambiental de la Reserva Biosfera de Sumaco: RBS Estrategia multi-organizacional e innovación local de los recursos naturales (2009–2011). Número de informe: Serie Sistematizaciones, Fascículo 2. Afiliación: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH. 2011. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/33909882/Escuela_de_Liderazgo_Ambiental_de_la_Reserva_de_Biosfera_Sumaco_RBS_Una_estrategia_multi_organizacional_e_innovadora_para_fomentar_la_gobernanza_local_de_los_recursos_naturales (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Tovar-Gálvez, J.C. Pedagogía ambiental y didáctica ambiental: Tendencias en la educación superior. Rev. Bras. Educ. 2017, 22, 519–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, N.M.; Gould, R.K.; Kelsey, E.; Fielding-Singh, F. Collaborative and Transformational Leadership in the Environmental Realm. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2014, 17, 360–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes Barrera, D.M.; Rojas Caldelas, R.I. Estilo de liderazgo predominante en organizaciones sociales dedicadas a la educación ambiental. Rev. Venez. Gerenc. 2017, 22, 657–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, M.C.; Ballard, H.L.; Oxarart, A.; Sturtevant, V.E.; Jakes, P.J.; Evans, E.R. Agencies, educators, communities, and wildfire: Partnerships to enhance environmental education for youth. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 22, 1098–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, H.; Cohen, F.; Warner, A. Youth and Environmental Action: Perspectives of Young Environmental Leaders on Their Formative Influences. J. Environ. Educ. 2009, 40, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Huang, F. Transformational Leadership, Organizational Innovation, and ESG Performance: Evidence from SMEs in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliman, M.A.; Abdou, A.H.; Ibrahim, M.F.; Al-Khaldy, D.A.W.; Anas, A.M.; Alrefae, W.M.M.; Salama, W. Impact of Green of Green Transformational Leadership on Employees’ Environmental Performance in the Hotel Industry Context: Does GreenWorkEngagement Matter? Sustainability 2023, 15, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgül, B.; Zehir, C. How Managers’ Green Transformational Leadership Affects a Firm’s Environmental Strategy, Green Innovation, and Performance: The Moderating Impact of Differentiation Strategy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, J.A.E.; Ejaz, F.; Ejaz, S. Green Transformational Leadership, GHRM, and Proenvironmental Behavior: An Effectual Drive to Environmental Performances of Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Li, W.; Mavros, C. Transformational Leadership and Sustainable Practices: How Leadership Style Shapes Employee Pro-Environmental Behavior. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leff, E. Pensamiento Ambiental Latinoamericano: Patrimonio de un Saber para la Sustentabilidad. ISEE Publicación Ocas. 2009, 6, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizina, Y.N. Decolonizing Sustainability through Indigenization in Canadian Post-Secondary Institutions. Societies 2022, 12, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonchingong Che, C.; Bang, H.N. Towards a “Social Justice Ecosystem Framework” for Enhancing Livelihoods and Sustainability in Pastoralist Communities. Societies 2024, 14, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiarti, T.; Purba, J.T.; Pramono, R. Enhancing Human Resource Quality in Lombok Model Schools: A Culture-Based Leadership Approach with Tioq, Tata, and Tunaq Principles. Societies 2024, 14, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales [SEMARNAT]. Estrategia Nacional de Educación Ambiental para la Sustentabilidad, en México, 1st ed.; SEMARNAT: Mexico City, México, 2006; pp. 27–47. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/semarnat/educacionambiental/documentos/estrategia-de-educacion-ambiental-para-la-sustentabilidad-en-mexico-version-extensa (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía [INEGI]. Rumbo al Censo. 2020. Available online: https://iieg.gob.mx/ns/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/CENSO-2020-Consulta.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Plan Municipal de Desarrollo. Municipio de Florencio Villarreal, Guerrero. H. Ayuntamiento Municipal Constitucional de Copala, Gro. 2021–2024. Available online: https://congresogro.gob.mx/63/ayuntamientos/plan-municipal/plan-municipal-de-desarrollo-florencio-villarreal-rpg.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Plan Municipal de Desarrollo. Municipio de Copala, Guerrero. H. Ayuntamiento Municipal Constitucional de Copala, Gro. 2021–2024. Available online: https://congresogro.gob.mx/63/ayuntamientos/plan-municipal/plan-municipal-copala.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Plan Municipal de Desarrollo. Municipio de Cuautepec, Guerrero. H. Ayuntamiento Municipal Constitucional de Cuautepec, Gro. 2021–2024. Available online: https://congresogro.gob.mx/63/ayuntamientos/plan-municipal/plan-de-desarrollo-municipal-2021-municipio-de-cuautepec.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Hintz, C.J.; Lackey, B.K. Assessing community needs for expanding environmental education programming. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2017, 16, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad [CONABIO]. Distribución de los Manglares en México en 1981. Available online: http://www.conabio.gob.mx/informacion/gis/maps/ccl/mexman70gw_c.zip (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad [CONABIO]. Distribución de los Manglares en México en 2010. Available online: http://www.conabio.gob.mx/informacion/gis/maps/ccl/mexman2010gw_c.zip (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad [CONABIO]. Distribución de los manglares en México en 2020. Available online: http://www.conabio.gob.mx/informacion/gis/maps/ccl/mx_man20gw_c.zip (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Pérez Serrano, G.; Nieto Martin, S. La investigación-acción en la educación formal y no formal. Enseñanza Teach. Rev. Interuniv. Didáctica 1993, 10, 177–198. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez Pozos, M. Algunas Reflexiones Sobre la Investigación Acción Colaboradora en la Educación. Revista Electrónica de Enseñanza de las Ciencias. (1) 1. Facultad de Ciencias de Educación. Universidad de Vigo. Campus de Ourense. 2002. Available online: https://repositorio.minedu.gob.pe/bitstream/handle/20.500.12799/1835/Algunas%20reflexiones%20sobre%20la%20investigacion-accion%20colaboradora%20de%20la%20educacion.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Stokking, H.; Van Aert, L.; Meijberg, W.; Kaskens, A. Evaluating Environmental Education; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; Ministry of Agriculture, Nature Management and Fisheries: Cambridge, UK, 2009; pp. 8–9. Available online: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/1999-069.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2021).

- Li, Z.; Xue, J.; Li, R.; Chen, H.; Wang, T. Environmentally Specific Transformational Leadership and employee´s pro-environmental behavior: The mediating roles of environmental passion and autonomous motivation. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Chang, T.W.; Lee, Y.S.; Yen, S.J.; Ting, C.W. How does sustainable leadership affect environmental innovation strategy adoption? The mediating role of environmental identity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, C.; Bohórquez, H.A.; Piña, D.C. El empoderamiento de los líderes ambientales escolares: Una estrategia para desarrollar la cultura ambiental en dos colegios públicos de Bogotá D.C. Rev. Tecné Epistem. Didaxis TED 2016, 599–605. Available online: https://revistas.upn.edu.co/index.php/TED/article/view/4620 (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Selby, S.T.; Cruz, A.R.; Ardoin, N.M.; Durham, W.H. Community-as-pedagogy: Environmental leadership for youth in rural Costa Rica. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 26, 1594–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; White, O.; Twigger-Ross, C. Our Bright Future Evaluation. Environmental Leadership: A Research Study; ERS Ltd.: Sheffield, UK; Collingwood Environmental Planning: Bristol, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.ourbrightfuture.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Our-Bright-Future-Environmental-Leadership-Study-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2023).

| Title | Authors and Year | Methodology | Sample | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foundations for Training Environmental Leaders [31] | Tovar-Gálvez (2012) | Literature review | Theoretical framework | Framework for leader training |

| Environmental Leadership School of Sumaco [32] | Torres (2011) | Systematized experience | 75 leaders (Ecuador) | Leaders develop socio-environmental solutions |

| Towards a Contextualized Citizen Environmental Education [33] | Tovar-Gálvez (2017) | Literature review | Theoretical analysis | Contextualized citizen education essential |

| Collaborative and Transformational Leadership [34] | Ardoin et al. (2014) | Narrative interviews | 12 leaders (USA) | Collaborative and transformational leadership key |

| Predominant Leadership in Environmental Education [35] | Reyes and Rojas (2017) | Qualitative questionnaire | 5 organizations (Mexico) | Transformational and collaborative styles dominate |

| Leadership Styles of Rural Leaders [16] | Springer et al. (2020) | Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire | 49 community leaders (Poland) | Transactional leadership predominates |

| Agencies, Educators, Communities, and Wildfire [36] | Monroe et al. (2015) | In-depth interviews | 7 youth programs (USA) | Community-driven projects empower youth |

| Youth and Environmental Action [37] | Arnold et al. (2009) | Qualitative interviews | 12 young leaders (Canada) | Formative influences on youth activism |

| Transformational Leadership and Environmental Social Governance (ESG) Performance [38] | Zhu and Huang (2023) | Survey | 500 employees (China) | Transformational leadership drives ESG |

| Impact of Green Transformational (GTL) Leadership in Hotels [39] | Suliman et al. (2023) | Quantitative questionnaire | 347 hotel employees (Egypt) | GTL enhances engagement and performance |

| Managers’ Green Transformational Leadership in Firms [40] | Özgül and Zehir (2023) | Survey | 315 firms (Turkey) | GTL boosts financial and green innovation |

| Green Transformational Leadership in Small–Medium Entrepreneurs (SMEs) [41] | Perez et al. (2023) | Quantitative questionnaire | SMEs (Pakistan) | GTL fosters sustainability in SMEs |

| Transformational Leadership and Pro-Environmental Behavior [42] | Ren et al. (2024) | Repeated questionnaires | 350 employees (China) | Environmental Specific Transformation Leadership (ESTL) promotes pro-environmental behavior |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rojas Casarrubias, C.; Aparicio López, J.L.; Rodríguez Alviso, C.; Castro Bello, M.; Villerías Salinas, S. Community Environmental Leadership and Sustainability: Building Knowledge from the Local Level. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3626. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083626

Rojas Casarrubias C, Aparicio López JL, Rodríguez Alviso C, Castro Bello M, Villerías Salinas S. Community Environmental Leadership and Sustainability: Building Knowledge from the Local Level. Sustainability. 2025; 17(8):3626. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083626

Chicago/Turabian StyleRojas Casarrubias, Concepción, José Luis Aparicio López, Columba Rodríguez Alviso, Mirna Castro Bello, and Salvador Villerías Salinas. 2025. "Community Environmental Leadership and Sustainability: Building Knowledge from the Local Level" Sustainability 17, no. 8: 3626. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083626

APA StyleRojas Casarrubias, C., Aparicio López, J. L., Rodríguez Alviso, C., Castro Bello, M., & Villerías Salinas, S. (2025). Community Environmental Leadership and Sustainability: Building Knowledge from the Local Level. Sustainability, 17(8), 3626. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083626