1. Introduction

Throughout history, humans have facilitated the spread of plants across different regions due to migration, trade, and globalization. These plant distributions can be either intentional—where plant species with desired traits are introduced for cultivation in a new region—or accidental, where unwanted plants or weeds are transported along with other goods during trans-Atlantic or trans-Saharan trade. Upon arriving in a new environment, alien plants first establish self-sustaining populations, also referred to as naturalization. Some of these naturalized plants remain confined to their introduced habitats without spreading or causing harm to native species. However, others spread rapidly, expanding into new areas and reaching population levels that outcompete indigenous plant species. These species are then termed “invasive alien species” (IASs) [

1]. Several hypotheses suggest that IASs thrive in their new environments because they are free from the constraints they faced in their native regions, such as natural enemies or competitors. As a result, the resources that would have been used to combat these pressures are redirected toward developing novel survival mechanisms, allowing these invasive plants to outcompete native species and disrupt ecosystem functions [

2].

Invasive alien species not only affect biodiversity and ecosystem function but also have significant impacts on human livelihoods. A plethora of studies emphasize the importance of documenting the perspectives of rural communities that are directly affected by invasives [

3]. Livelihoods in rural areas, which are often tied to crop and livestock farming, are directly influenced by invasive species and understanding how invasive plants impact these livelihoods is crucial for making informed management decisions and preventing conflicts, particularly in cases where local communities have found ways to benefit from these invasive alien plant species [

4]. Although the term “invasive alien species” generally conveys negative connotations, research has shown that people’s perceptions of the negative, positive, or nuanced impact of these species on their livelihood vary, depending on their interactions with the plants over time.

Numerous studies have documented the detrimental effects of invasive plants on agricultural sustainability. For instance,

Parthenium hysterophorus L. has been found to harm crops and livestock in Pakistan [

5], while

Mikania micrantha Kunth reduced forest resources essential for livelihoods in Nepal [

6]. In East Africa,

Lantana camara L. diminished forage availability and crop yields, while its control costs pose a threat to food security [

7]. These negative impacts of invasive species on livelihoods have prompted government efforts to minimize their spread. For example, South Africa implemented national-scale eradication programs, such as “Working for Water”, aimed at eliminating invasive species like Acacia, Eucalyptus, Prosopis, and Pinus. However, these efforts, costing over USD 450 million, have been met with varying degrees of success [

8]. Conversely, not all interactions with invasive species are negative. For example, a study by van Wilgen et al. [

9] revealed that local communities reported both positive and negative impacts of

Vernonanthura polyanthes (Spreng.) based on how they had used the plant over time. Similarly, some people who used

Acacia dealbata for fuel or construction materials viewed it positively. At the same time, crop farmers whose land had been invaded by the species perceived it negatively [

10]. Despite

L. camara’s adverse effects on biodiversity, it has been used as a wood substitute when other resources were scarce [

11]. These examples highlight the importance of understanding the perspectives of rural communities that directly interact with invasive species, especially when management measures and governmental policies are to be implemented.

Chromolaena odorata (L.) King and Robinson (Asteraceae: Eupatorieae) is a weed that was accidentally introduced to Nigeria in 1937 [

12] and has since posed a serious threat to ecosystem integrity. It disrupts vegetation structure, composition, and flora–fauna interactions, leading to biodiversity loss [

13]. The weed’s invasive success is attributed to its high reproductive rate, rapid growth, allelopathic properties, and resilience in diverse ecological zones [

14,

15]. When in high abundance,

C. odorata forms dense thickets along forest edges and fallow lands, suppressing native vegetation and increasing the risk of wildfires [

16]. Studies in southern Nigeria demonstrated that the high density of

C. odorata reduces the species diversity of native plant species [

17], while similar findings have been reported in Nepal’s forest ecosystems [

18]. Given the detrimental effects of

C. odorata on ecosystems, it is critical to examine how it impacts human livelihoods, especially in rural areas where people depend on land resources for survival.

Chromolaena odorata has plagued farming communities for decades, causing significant harm to farmers’ livelihoods. Its aggressive spread across plantations, farmlands, and fallow areas has directly impacted human well-being in these regions. In addition to the costs of controlling the weed, its tendency to fuel wildfires and reduce crop yields poses further challenges. Studies in East Africa and West Timor revealed that

C. odorata infested grazing lands, resulting in significant losses for livestock and crop farmers [

19,

20]. Despite these negative impacts, some local communities have found ways to benefit from the weed. For instance, it has been reported to improve soil fertility and possess ethnopharmacological benefits [

15,

21,

22,

23]. Understanding the perspectives of local dwellers who interact directly with

C. odorata is crucial, as their insights can provide valuable information about both the positive and negative effects of the weed.

In southern Nigeria, research on

C. odorata has primarily focused on its impact on native plant density, its ethnomedicinal and agricultural uses, and its potential for biogas production, as well as efforts to identify biological control agents and their applications in classical biocontrol [

15,

24,

25,

26,

27]. However, there is a need for comprehensive information regarding the effects of

C. odorata on people’s livelihoods. Some of the positive and negative impacts of the weed on both biodiversity and livelihoods have been reviewed [

15], but the conclusions thereof were largely anecdotal and require further empirical investigation to provide clearer insights and propose ecosystem-friendly management strategies.

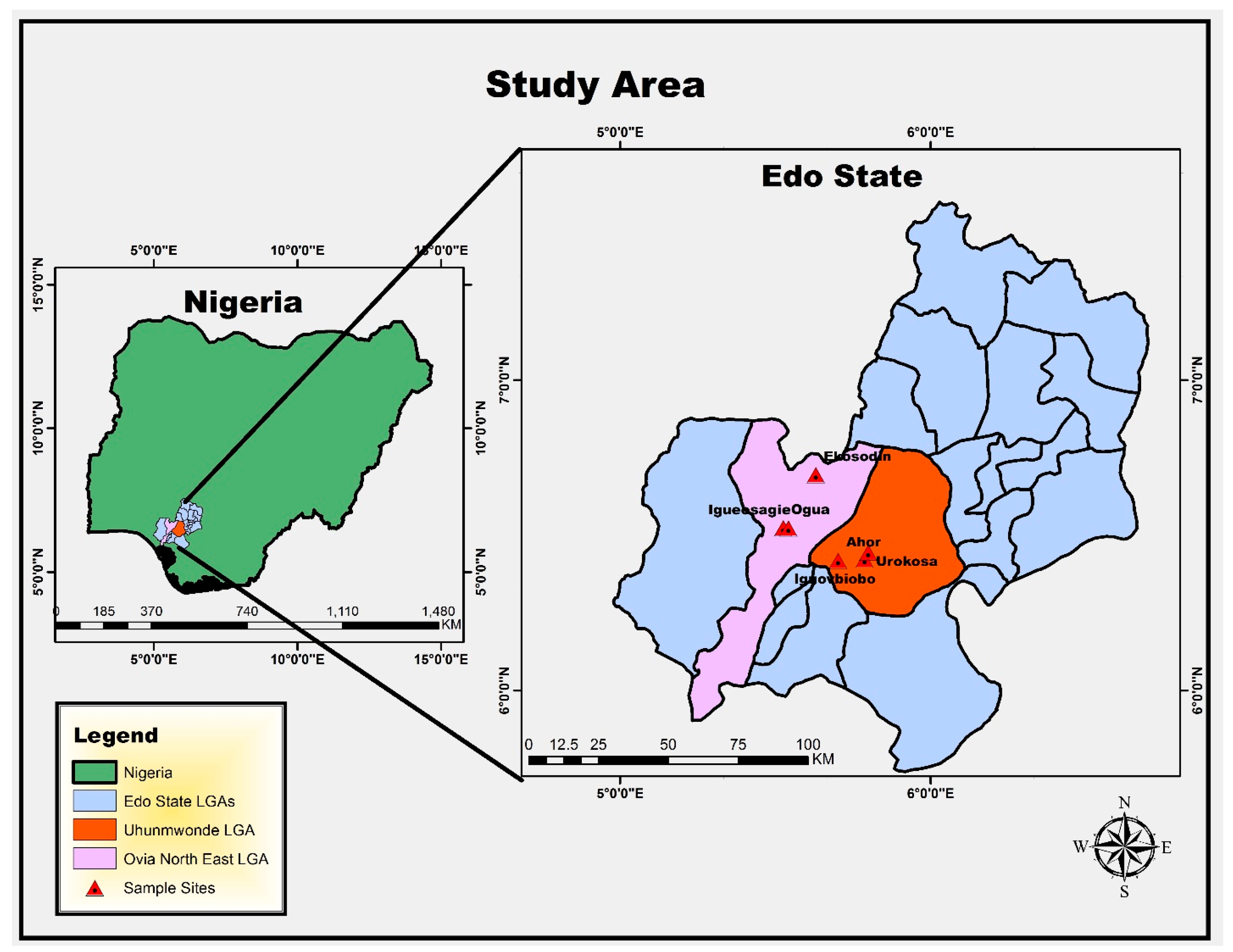

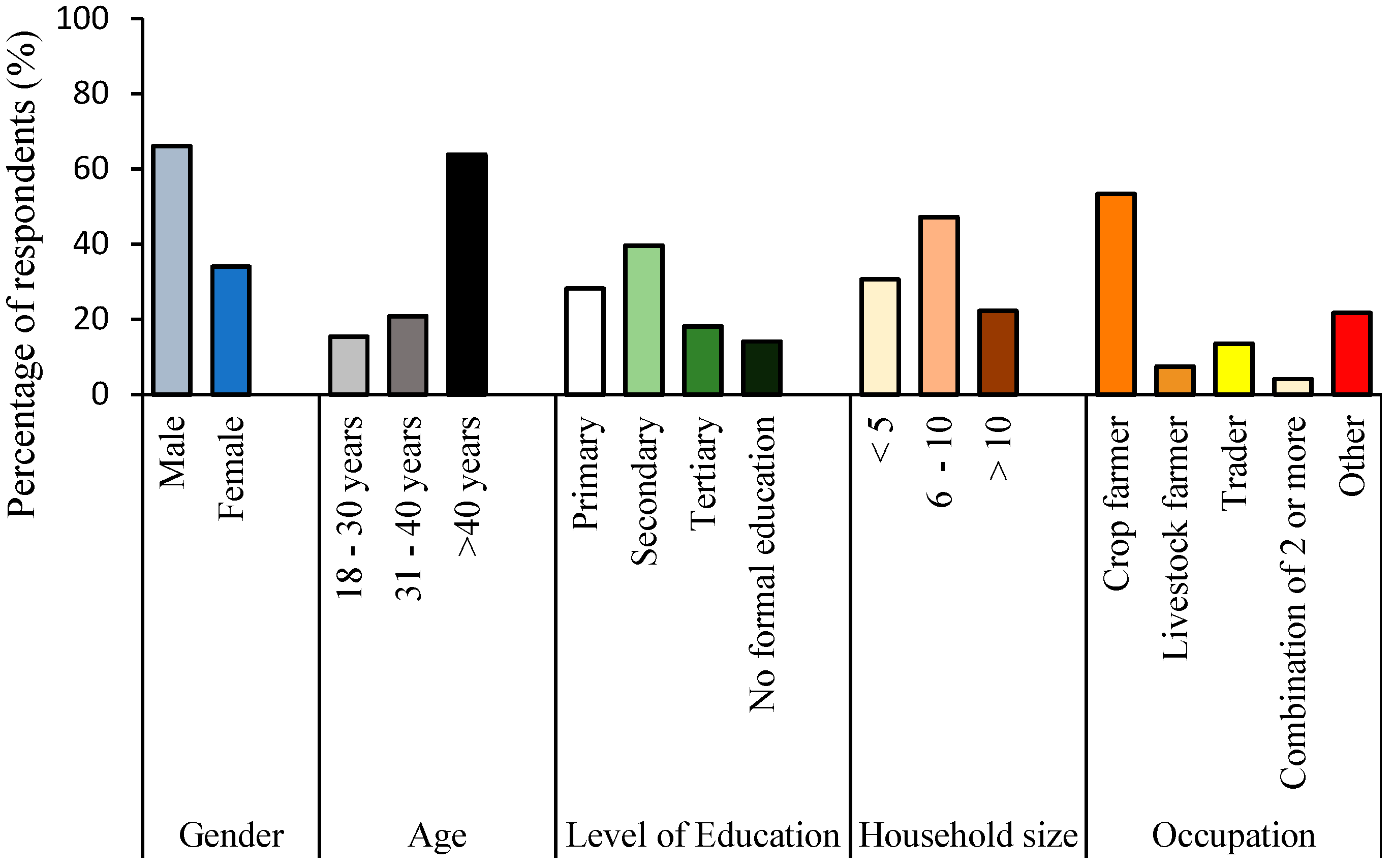

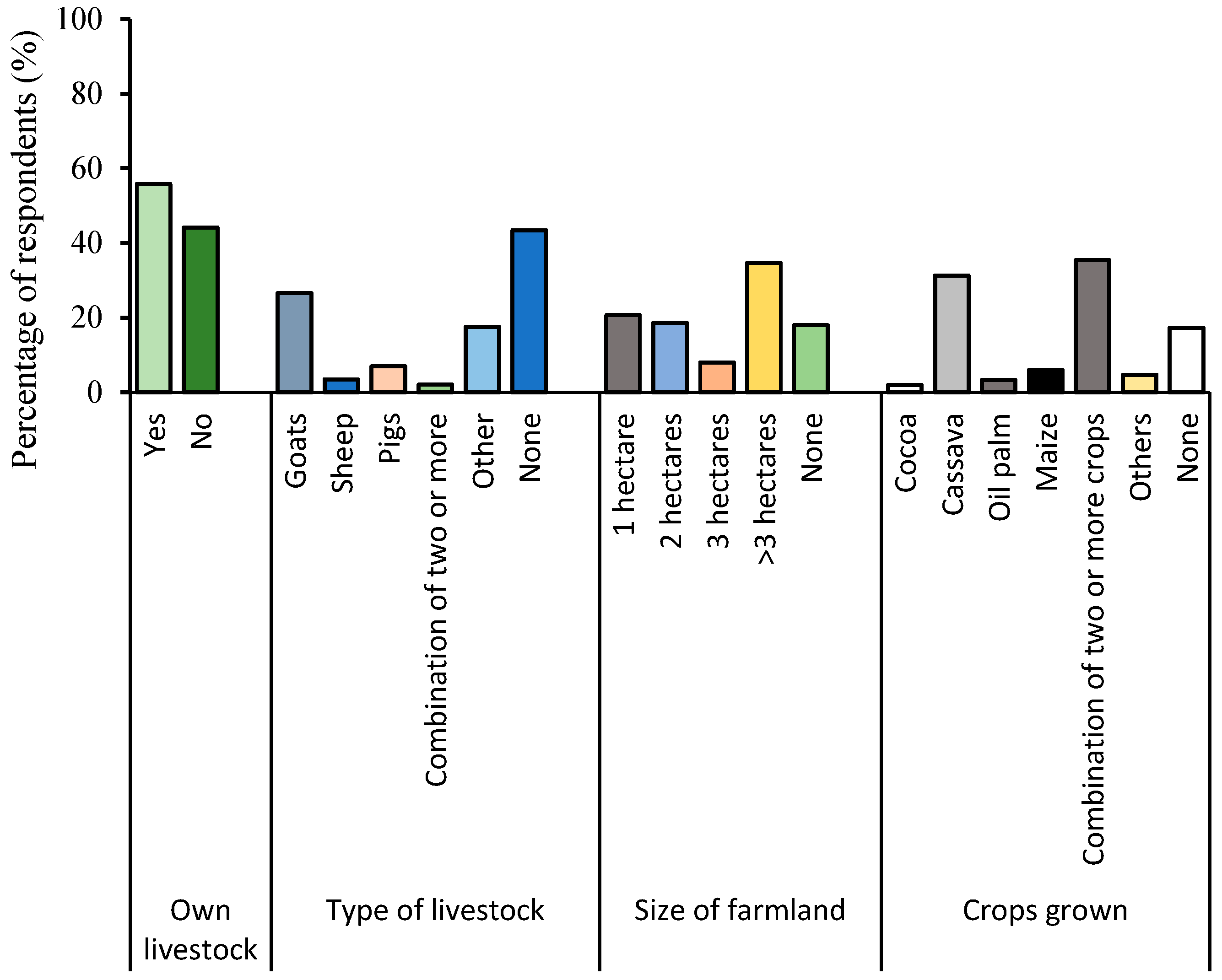

This study utilized participatory rural appraisal techniques to assess local perceptions of C. odorata and its effects on rural communities’ livelihoods. The primary objective was to explore the weed’s impact on crop and livestock production, wildlife, and the health conditions of the local inhabitants while also evaluating how local communities have harnessed the plant for their benefit. Additionally, this paper examines the strategies employed by the inhabitants to manage C. odorata in the region.

4. Discussion

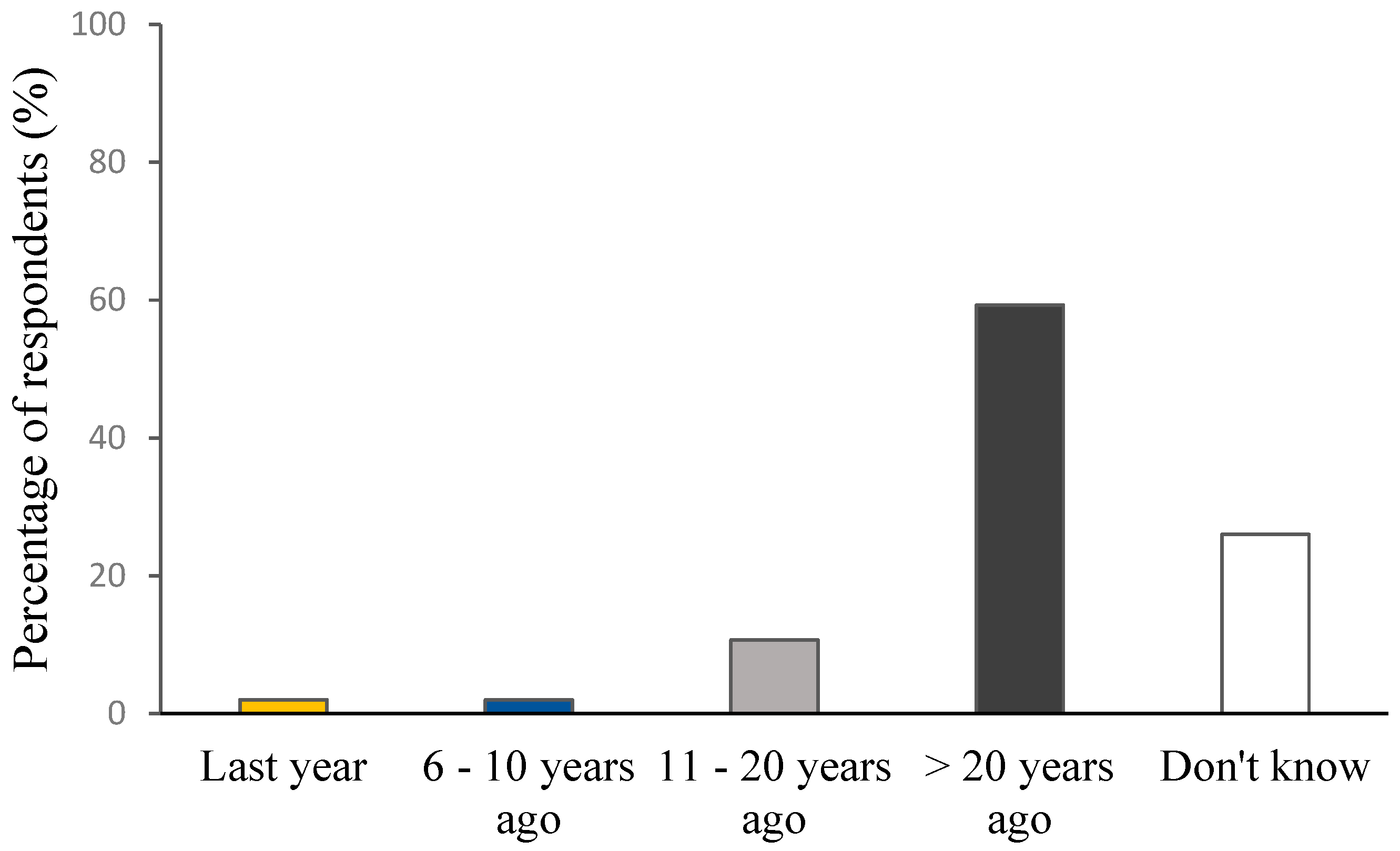

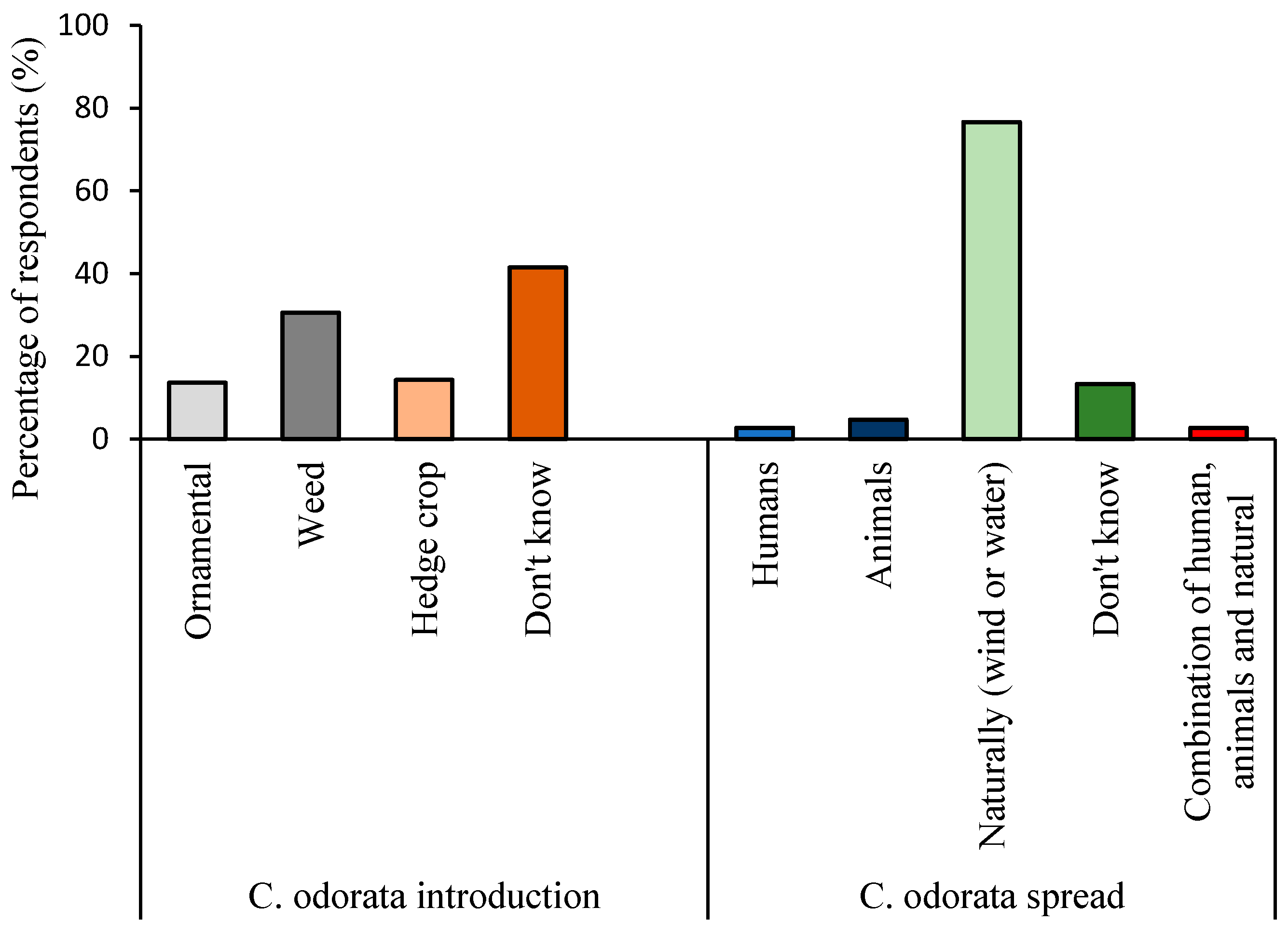

Chromolaena odorata is a well-known invasive weed in Southern Nigeria, and a significant majority of rural inhabitants are familiar with its presence. Although historical records show that it was first documented in Nigeria in 1937 [

12], most respondents in the study area reported its widespread occurrence by 1956. The weed’s spread can explain this discrepancy in reported arrival times. After arriving in 1937,

C. odorata likely went through the less prominent but no less profound stages of invasion, comprising colonization, naturalization, and spread, before becoming widely noticeable [

1]. According to the theories of plant invasion, an exotic plant must overcome various biotic and abiotic barriers during the acclimatization stages before it becomes invasive, which usually takes many years [

2,

33]. The initial colonization and naturalization phases may have gone unnoticed, only becoming apparent when the weed started affecting the livelihoods of locals, hence the time gap in when it was first perceived. Taken together, from the first documented evidence to the locals’ perception of its arrival, it is anecdotally suggestive of a little short of two decades for

Chromolaena’s lag phase.

Interestingly, the majority of respondents in this study consider

C. odorata beneficial, particularly for its medicinal (or ethnobotanical) and agricultural fertility uses [

23,

34,

35]. Empirical support for the locals’ perceptions of the soil-improving capacity of

C. odorata abound in the literature [

35,

36,

37,

38]. For instance, Tondoh and coworkers [

36] reported an increase in key soil macronutrients, mineral pools, soil macroinvertebrate abundance, and overall soil biomass in

C. odorata-dominated sites compared to control plots. Similarly,

C. odorata was found to be a more effective fallow species than

Calliandra calothyrsus and

Pueraria phaseoloides in enhancing soil fertility [

37]. Others [

35,

38] have enunciated

C. odorata’s efficiency in soil nutrient accretion, although the extent of nutrient enrichment largely depended on the duration of the fallow period. In addition to its role in nutrient cycling,

C. odorata has been identified as an effective organic mulch (15). In fact, records [

39,

40] indicate that its rapid decomposition facilitates nutrient release, thereby improving soil fertility. Moreover,

C. odorata has been demonstrated to enhances soil microbial biomass and enzymatic activities [

41], which may contribute to its rapid biodegradability and its competitive advantage over native vegetation [

42].

Beyond its effects on soil properties,

C. odorata has also been linked to improved agricultural productivity, as evident in the increase in crop yields following fallow periods dominated by

C. odorata. For example, notable yield improvements in yam and rice cultivated on previously

C. odorata-occupied soils have been reported [

43,

44,

45]. The most plausible explanation for these yield improvements is the enhanced availability of essential nutrients following

C. odorata-mediated soil enrichment.

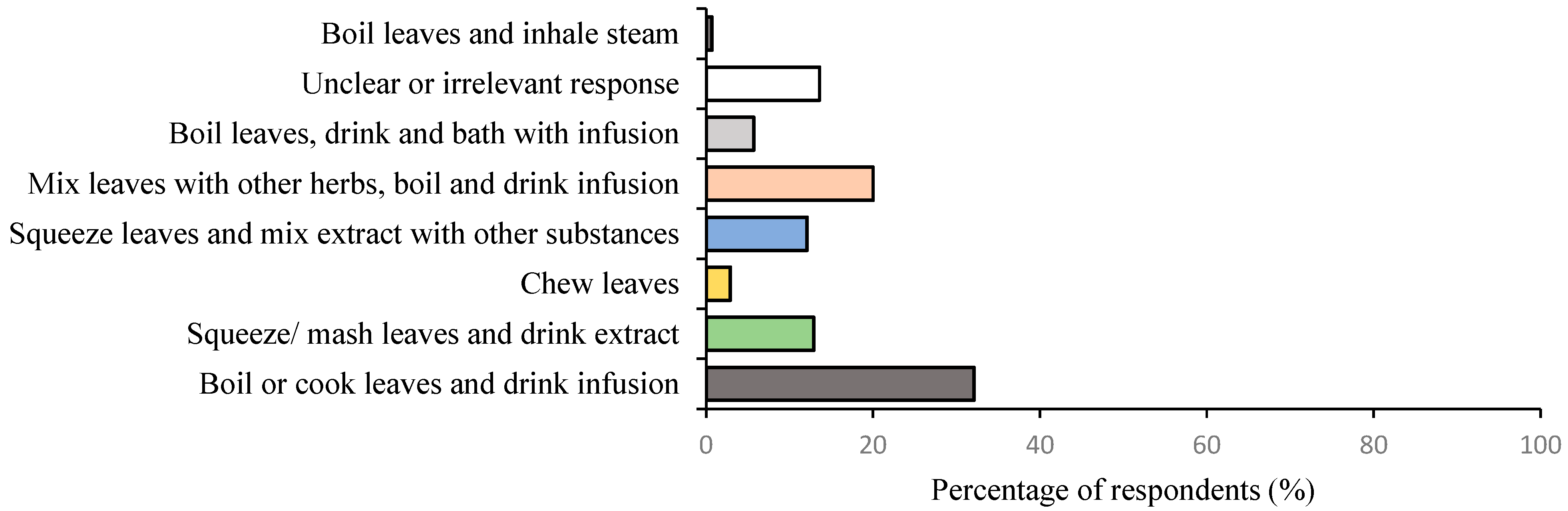

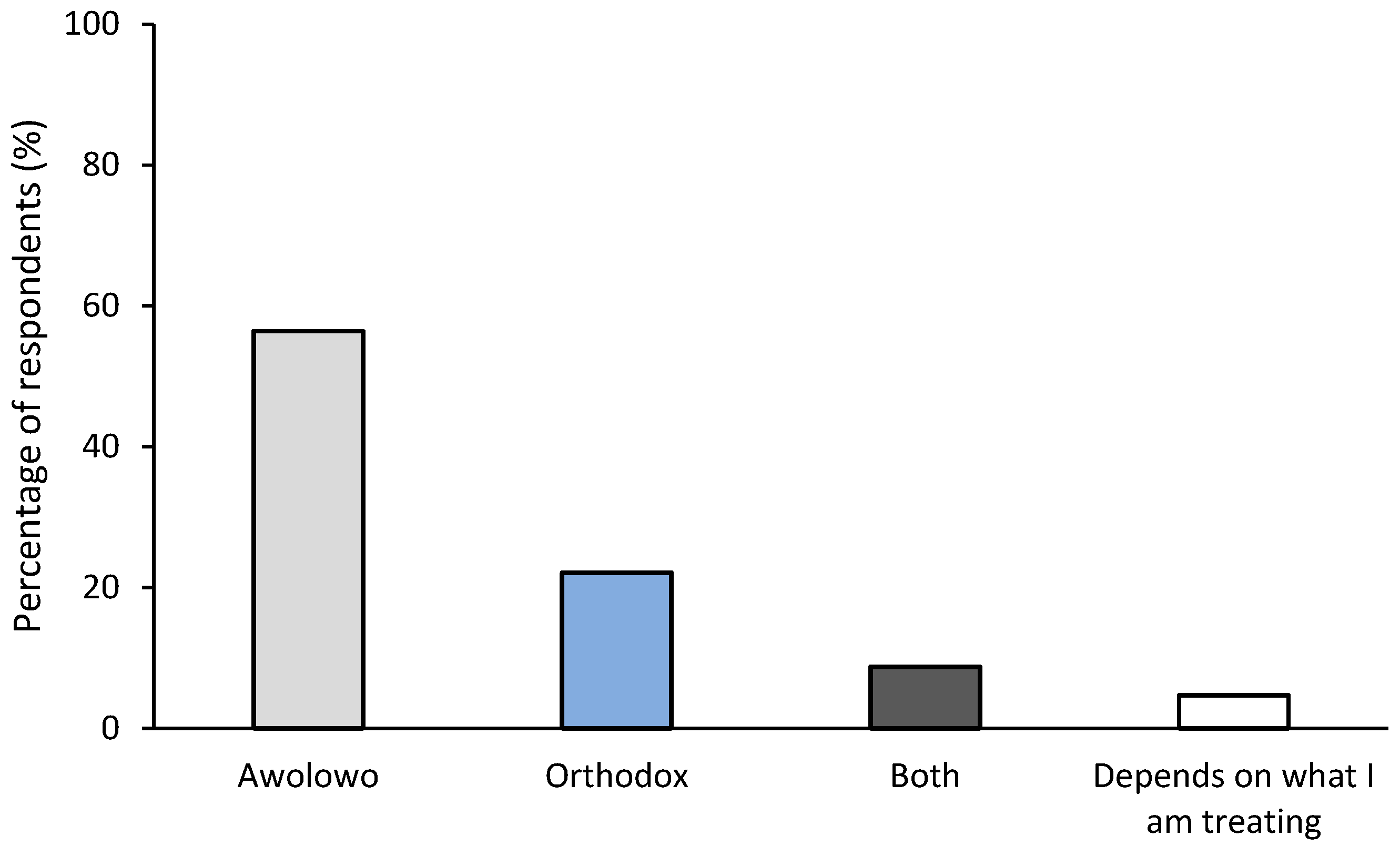

In rural areas, where access to healthcare is limited, villagers often rely on affordable, readily available alternatives like medicinal herbs. This was demonstrated in this study when over 50% of the respondents indicated a preference for using aqueous leaf extracts of

C. odorata after mild heating to treat fever due to its low cost and accessibility. Farmers, who are frequently exposed to injuries during agricultural work, often use the weed to stop bleeding, which is seen as a significant and beneficial first aid before seeking orthodox medical assistance. Furthermore, many respondents believe in the potency of herbs to heal various ailments because they believe in traditional medicine prepared through herbs that are directly sourced from nature. Over 80% of respondents claimed that the weed plays an important role in agriculture as a fallow plant, rejuvenating nutrient-depleted soils. Similar studies [

46,

47] have highlighted

C. odorata’s use in traditional medicine and agriculture. However, contrary to these reports,

C. odorata provided no benefits in East Africa, where its recent introduction caused sudden and devastating impacts [

20]. We consider that the most plausible explanation for these obverse patterns could be because, for East Africans, the presence of the weed is relatively new, and the people are yet to adapt to the reality of the invasive weed, unlike in Ghana and Nigeria, where a longer human–chromolaena interaction periods allowed its integration into the daily lives of rural-dwelling West Africans [

22,

46]. In Nigeria, in 1975, when the weed was fairly new to the inhabitants, the weed’s devastating impact on oil palm plantations and crop farms prompted a large-scale biological control effort after mechanical and chemical control methods failed to control the weed effectively [

48]. Despite the introduction of the biocontrol agent

Pareuchaetes pseudoinsulata to manage the weed, it was unsuccessful. Because subsequent large-scale control efforts were not recorded, the locals likely adapted to

C. odorata by utilizing the weed for several purposes, which metamorphosed into its beneficial properties today, hence reiterating the fact that as people interact with an invasive weed, they discover novel ways to utilize it.

Despite the perceived benefits, this study also reveals that

C. odorata poses a substantial economic burden on farmers due to its negative impact on crop yields and quality. More than half of the respondents indicated that the weed’s encroachment on farmlands reduces crop productivity. In Ghana, its initial invasion led to a sharp decline in staple crop yields, forcing farmers to abandon affected areas [

14]. Our finding aligns with previous studies from Tanzania and Kenya, where

C. odorata similarly dominated agricultural landscapes, diminishing yields [

19], while in Nepal,

C. odorata also affected the productivity of key crops [

47]. Other invasive weeds, such as

Parthenium hysterophorus, have caused crop declines in Pakistan, affecting potato, sugarcane, and maize production [

5]. Likewise,

Vernonanthura polyanthes and

Lantana camara have negatively impacted agricultural productivity in various communities [

11,

49]. Furthermore, over 60% of respondents in this study reported that

C. odorata hinders movement due to the dense thickets it forms, a phenomenon also observed with

Mikania micrantha in Nepal, which obstructed human and wildlife movement [

6].

Despite its invasiveness, over 70% of respondents find

C. odorata relatively easy to control, using manual methods such as uprooting or cutting (slashing with cutlasses), with few opting for herbicides. Similar reports from Ghana indicate that the use of herbicides to control the weed is rare [

21]. In contrast, weeds like

Parthenium hysterophorus are more difficult to manage, requiring substantial financial costs for control [

5]. Nevertheless, farmers in the study area reported encountering mainly newly emerged shoots of

C. odorata, which are easier to remove manually.

However, the respondents claimed that Elephant grass (

Pennisetum purpureum L.) poses a more significant challenge to farmers than

C. odorata. Elephant grass, commonly called Napier grass, is a member of the Poaceae family, and it is native to tropical Africa. Farmers in the communities surveyed alluded to the spread of Elephant grass to the nomadic cattle herdsmen (commonly referred to as Fulani herders) who migrate from northern Nigeria to the southern parts of the country in search of grazing land for their cattle. The farmers believe that the weed’s seeds are dispersed through cattle faeces, contributing to its rapid spread across farmlands. Respondents widely regarded elephant grass as a troublesome weed because of its resilience, rapid regrowth (even after mechanical removal), and resistance to pesticides, resulting in difficulty in managing this weed and contributing to low yield in crop farming in the area. Despite its invasive tendencies, many scientific studies have emphasized the potential benefits of Elephant grass as fodder for cattle and raw material for biofuel production [

50,

51].

While Elephant grass serves as a valuable resource in some contexts, its capacity for rapid spread and regrowth remains a serious challenge for rural farmers in the study area, most of whom are crop farmers rather than livestock farmers. Consequently, they do not derive economic benefits from the grass, making its aggressive growth much more of a threat than an asset, as opposed to how some perceive

C. odorata. Several factors contribute to the prioritization of Elephant grass management over

C. odorata. Firstly, Elephant grass is highly persistent and vigorous, exhibiting rapid growth [

51] that allows it to outcompete crops for essential resources such as light, water, and nutrients. Its ability to thrive in areas with precipitation above 1000 mm, its high yield capacity, and its resistance to pests and diseases makes the study site particularly suitable for its proliferation, further enhancing its dominance in agricultural fields. Farmers in the study area find Elephant grass particularly difficult to control due to its resilience. Traditional methods such as slashing are largely ineffective because of its rapid regrowth, while its high photosynthetic efficiency allows it to recover quickly even after herbicide application [

51]. Consequently, managing Elephant grass requires more effort and resources, making it a greater concern for farmers than

C. odorata, despite the latter’s well-documented ecological impacts.

Unsurprisingly, the locals perceive

C. odorata as a rapidly spreading plant. This aligns with the concept of “propagule pressure”, which posits that invasive plants with high seed production are more likely to dominate their habitats [

52]. The weed’s prolific seed production and rapid germination have enabled its continued spread in invasive regions. A similar situation was observed in Kenya with the invasive

Prosopis species, which continued to spread despite being incorporated into local livelihoods [

53]. In contrast, in Ghana,

C. odorata was found to be decreasing in density, likely due to the successful establishment of biocontrol agents like

Pareuchaetes pseudoinsulata and

Cecidochares connexa in that region [

21]. However, the effectiveness of biocontrol can vary depending on ecological context, and there are cases where unintended consequences have arisen. For instance, Havens et al. [

54] cautions that the promotion of biocontrol as the most effective approach for invasive weed management is sometimes overstated due to potential non-target effects. This highlights the need for rigorous, case-specific assessments of novel biocontrol agents before widespread implementation, particularly as past biocontrol efforts against

C. odorata in Nigeria, such as the introduction of

P. pseudoinsulata, were unsuccessful [

46]. While using biocontrol agents remains a valuable tool in managing invasive weeds [

55], its application should be complemented with integrated management strategies [

54,

56].