Recycled CO2 in Consumer Packaged Goods: Combining Values and Attitudes to Examine Europeans’ Consumption Intentions

Abstract

1. Introduction

“The end of the fossil fuel era is assured. The only questions are: Will we move fast enough to limit the worst of climate chaos? And will the transition to renewables be fair, just and equitable? It is up to all of us to ensure the answer to both these questions is—yes”[1]. UN Secretary-General’s video message to the International Energy Agency’s 50th Anniversary Celebration in Paris, February 2024.

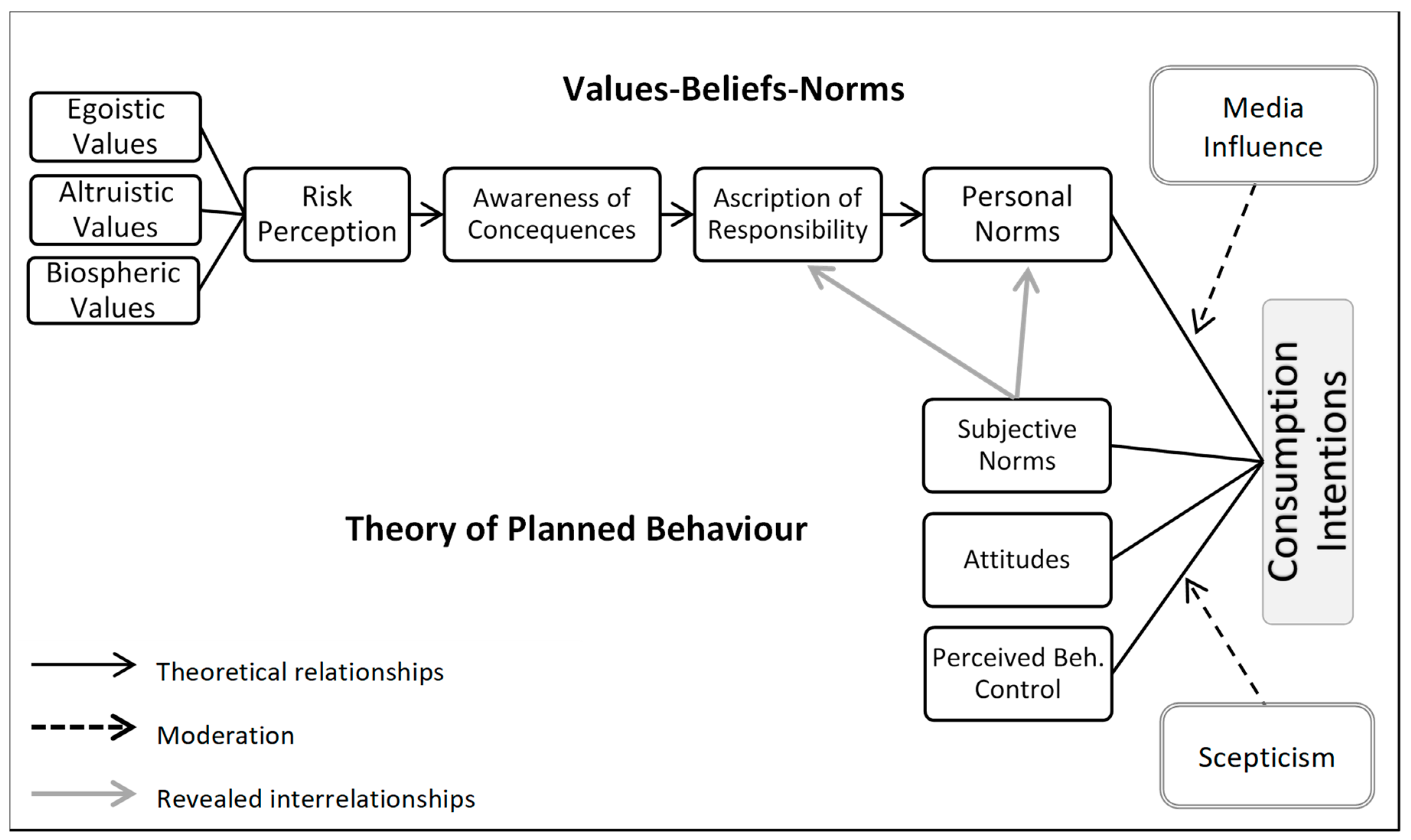

2. Theoretical Background

3. Literature Review and Hypotheses

3.1. Values

3.2. Beliefs

3.3. Personal Norms

3.4. Intentions

3.5. Scepticism and Media Influence

4. Methodology

5. Results

5.1. Demographics

5.2. Structural Equation Modelling (SEM)

5.2.1. Measurement Model

5.2.2. Common Method Variance

5.2.3. Structural Model

5.2.4. Moderation

6. Discussion

7. Limitations and Future Research Suggestions

8. Conclusions

9. Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Secretary-General’s Video Message to the International Energy Agency’s 50th Anniversary Celebration. Available online: https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/statement/2024-02-14/secretary-generals-video-message-the-international-energy-agencys-50th-anniversary-celebration (accessed on 26 March 2024).

- United Nations. Now Must Be the Time for Action. Available online: https://www.un.org/climatechange?gclid=Cj0KCQjwmvSoBhDOARIsAK6aV7iBzbPo0wBThL6QUxeTWxg1ijjjWv3j-mlPnhet0WiOWjJCLMv90CAaAtQ3EALw_wcB (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- European Union. Climate Change: What the EU Is Doing. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/climate-change/ (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Goldberg, M.H.; Gustafson, A.; van der Linden, S. Leveraging Social Science to Generate Lasting Engagement with Climate Change Solutions. One Earth 2020, 3, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.; Discetti, R.; Bellucci, M.; Acuti, D. SMEs Engagement with the Sustainable Development Goals: A Power Perspective. J. Bus Res. 2022, 149, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Climate Change: Annual Report 2020; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 9789292191979. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/UNFCCC_Annual_Report_2021.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2024).

- Ding, Z.; Jiang, X.; Liu, Z.; Long, R.; Xu, Z.; Cao, Q. Factors Affecting Low-Carbon Consumption Behavior of Urban Residents: A Comprehensive Review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 132, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, H.; Slade, E.L.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Examining Antecedents of Consumers’ pro-Environmental Behaviours: TPB Extended with Materialism and Innovativeness. J. Bus Res. 2021, 122, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change. Global Warming of 1.5 °C; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; ISBN 9781009157940. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Thomas, G. Examining the Impact of Pro-Environmental Factors on Sustainable Consumption Behavior and Pollution Control. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social: The Case of Environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, L.M.; Shiu, E.; Shaw, D. Who Says There Is an Intention–Behaviour Gap? Assessing the Empirical Evidence of an Intention–Behaviour Gap in Ethical Consumption. J. Bus Ethics 2016, 136, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElHaffar, G.; Durif, F.; Dubé, L. Towards Closing the Attitude-Intention-Behavior Gap in Green Consumption: A Narrative Review of the Literature and an Overview of Future Research Directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 122556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, M.; Chatzidakis, A.; Goworek, H.; Shaw, D. Consumption Ethics: A Review and Analysis of Future Directions for Interdisciplinary Research. J. Bus Ethics 2021, 168, 215–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaremohzzabieh, Z.; Ismail, N.; Ahrari, S.; Abu Samah, A. The Effects of Consumer Attitude on Green Purchase Intention: A Meta-Analytic Path Analysis. J. Bus Res. 2021, 132, 732–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Alfaro-Barrantes, P. Pro-Environmental Behavior in the Workplace: A Review of Empirical Studies and Directions for Future Research. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2015, 120, 137–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stampa, E.; Schipmann-Schwarze, C.; Hamm, U. Consumer Perceptions, Preferences, and Behavior Regarding Pasture-Raised Livestock Products: A Review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 82, 103872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canlas, I.P.; Karpudewan, M.; Mohamed Ali Khan, N.S. More than Twenty Years of Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Environmentalism: What Has Been and yet to Be Done? Interdiscip. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2022, 18, e2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Moreno, F. Driving Values to Actions: Predictive Modeling for Environmentally Sustainable Product Purchases. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 23, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ruiz-Menjivar, J.; Luo, B.; Liang, Z.; Swisher, M.E. Predicting Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Behaviors in Agricultural Production: A Comparison of the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Value-Belief-Norm Theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 68, 101408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, M.; Zouaghi, F.; Lera-López, F.; Faulin, J. An Extended Behavior Model for Explaining the Willingness to Pay to Reduce the Air Pollution in Road Transportation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 128134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebarajakirthy, C.; Sivapalan, A.; Das, M.; Maseeh, H.I.; Ashaduzzaman, M.; Strong, C.; Sangroya, D. A Meta-Analytic Integration of the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Value-Belief-Norm Model to Predict Green Consumption. Eur. J. Mark. 2024, 58, 1141–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiserowitz, A. Climate Change Risk Perception and Policy Preferences: The Role of Affect, Imagery, and Values. Clim. Chang. 2006, 77, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Eroglu, D.; Scholder, E.P. The Development and Testing of a Measure of Skepticism toward Environmental Claims in Marketers’ Communications. J. Consum. Aff. 1998, 32, 30–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearden, W.O.; Netemeyer, R.G.; Teel, J.E. Measurement of Consumer Susceptibility to Interpersonal Influence. J. Consum. Res. 1989, 15, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Global Edition; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 9780135153093. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D. The “New Environmental Paradigm”. J. Environ. Educ. 1978, 9, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research [Internet]; Addition-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. On Behaving in Accordance with One’s Attitudes. In Consistency in Social Behavior: The Ontario Symposium; Zana, M.P., Higgins, T.E., Herman, P.C., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, MI, USA, 1982; Volume 2, pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S. Normative Explanations of Helping Behavior: A Critique, Proposal, and Empirical Test. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1973, 9, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 10, 221–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Kalof, L.; Dietz, T.; Guagnano, G.A. Values, Beliefs, and Proenvironmental Action: Attitude Formation toward Emergent Attitude Objects. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 25, 1611–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behaviour: Reactions and Reflections. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Q.C.; Jian, I.Y.; Chi, H.L.; Yang, D.; Chan, E.H.W. Are You an Energy Saver at Home? The Personality Insights of Household Energy Conservation Behaviors Based on Theory of Planned Behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 174, 105823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Long, X.; Li, L.; Wang, Q.; Ding, X.; Cai, S. Extending Theory of Planned Behavior in Household Waste Sorting in China: The Moderating Effect of Knowledge, Personal Involvement, and Moral Responsibility. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 7230–7250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretter, C.; Unsworth, K.L.; Russell, S.V.; Quested, T.E.; Doriza, A.; Kaptan, G. Don’t Put All Your Eggs in One Basket: Testing an Integrative Model of Household Food Waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 185, e106442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, M.A.; Hanafiah, M.H.; Kunjuraman, V. Tourists’ Intention to Visit Green Hotels: Building on the Theory of Planned Behaviour and the Value-Belief-Norm Theory. J. Tour. Futures 2024, 10, 255–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, N. Factors Influencing the Purchase Intention for Recycled Products: Integrating Perceived Risk into Value-Belief-Norm Theory. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkargkavouzi, A.; Halkos, G.; Matsiori, S. Environmental Behavior in a Private-Sphere Context: Integrating Theories of Planned Behavior and Value Belief Norm, Self-Identity and Habit. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 148, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, D.; Hahn, R. Understanding Collaborative Consumption: An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior with Value-Based Personal Norms. J. Bus Ethics 2019, 158, 679–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.F. Selecting Environmental Psychology Theories to Predict People’s Consumption Intention of Locally Produced Organic Foods. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; Cavallo, C.; Catellani, P.; Del Giudice, T.; Cicia, G. Why Do Consumers Intend to Purchase Natural Food? Integrating Theory of Planned Behavior, Value-Belief-Norm Theory, and Trust. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W. Toward a Theory of Ethical Consumer Intention Formation: Re-Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. AMS Rev. 2020, 10, 260–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. Measuring Endorsement of the New Ecological Paradigm: A Revised NEP Scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Mas’od, A.; Sulaiman, Z. Moderating Effect of Collectivism on Chinese Consumers’ Intention to Adopt Electric Vehicles—An Adoption of VBN Framework. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornara, F.; Molinario, E.; Scopelliti, M.; Bonnes, M.; Bonaiuto, F.; Cicero, L.; Admiraal, J.; Beringer, A.; Dedeurwaerdere, T.; de Groot, W.; et al. The Extended Value-Belief-Norm Theory Predicts Committed Action for Nature and Biodiversity in Europe. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2020, 81, 106338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Swidi, A.; Saleh, R.M. How Green Our Future Would Be? An Investigation of the Determinants of Green Purchasing Behavior of Young Citizens in a Developing Country. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 13436–13468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Fitzgerald, A.; Shwom, R. Environmental Values. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 335–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, E.M.; Nguyen, B.; Mutum, D.S.; Yap, S.-F. Pro-Environmental Behaviours and Value-Belief-Norm Theory: Assessing Unobserved Heterogeneity of Two Ethnic Groups. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.F. Integrating the Value–Belief–Norm Model and the Theory of Planned Behavior for Explaining Consumers’ Purchase Intention of Suboptimal Food. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 3483–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Kim, W.; Kim, J.J. Application of the Value-Belief-Norm Model to Environmentally Friendly Drone Food Delivery Services: The Moderating Role of Product Involvement. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 1775–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Gupta, A. Pro-Environmental Behaviour among Tourists Visiting National Parks: Application of Value-Belief-Norm Theory in an Emerging Economy Context. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical Advances and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M.P., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992; Volume 25, pp. 1–65. ISBN 0065-2601. [Google Scholar]

- Steg, L.; Dreijerink, L.; Abrahamse, W. Factors Influencing the Acceptability of Energy Policies: A Test of VBN Theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Keizer, K.; Perlaviciute, G. An Integrated Framework for Encouraging Pro-Environmental Behaviour: The Role of Values, Situational Factors and Goals. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoquab, F.; Jaini, A.; Mohammad, J. Does It Matter Who Exhibits More Green Purchase Behavior of Cosmetic Products in Asian Culture? A Multigroup Analysis Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wong, P.P.W.; Narayanan Alagas, E. Antecedents of Green Purchase Behaviour: An Examination of Altruism and Environmental Knowledge. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 14, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hwang, J.; Lee, M.J. The Value–Belief–Emotion–Norm Model: Investigating Customers’ Eco-Friendly Behavior. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 590–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, A.B.; Steg, L.; Gorsira, M. Values versus Environmental Knowledge as Triggers of a Process of Activation of Personal Norms for Eco-Driving. Environ. Behav. 2018, 50, 1092–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaung, W.; Carrasco, L.R.; Richards, D.R.; Shaikh, S.F.E.A.; Tan, P.Y. The Role of Urban Nature Experiences in Sustainable Consumption: A Transboundary Urban Ecosystem Service. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 601–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L. Values, Norms, and Intrinsic Motivation to Act Proenvironmentally. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016, 41, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. The Refined Theory of Basic Values. In Values and Behavior; Roccas, S., Sagiv, L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, G.M.; Moreira, N.; Bouman, T.; Ometto, A.R.; van der Werff, E. Towards Circular Economy for More Sustainable Apparel Consumption: Testing the Value-Belief-Norm Theory in Brazil and in The Netherlands. Sustainability 2022, 14, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trautwein, U.; Babazade, J.; Trautwein, S.; Lindenmeier, J. Exploring Pro-Environmental Behavior in Azerbaijan: An Extended Value-Belief-Norm Approach. J. Islam. Mark. 2023, 14, 523–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Stern, P.C.; Rycroft, R.W. Definitions of Conflict and the Legitimation of Resources: The Case of Environmental Risk. Sociol. Forum 1989, 4, 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megeirhi, H.A.; Woosnam, K.M.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Ramkissoon, H.; Denley, T.J. Employing a Value-Belief-Norm Framework to Gauge Carthage Residents’ Intentions to Support Sustainable Cultural Heritage Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1351–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awais, M.; Fatima, T.; Awan, T.M. Assessing Behavioral Intentions of Solar Energy Usage through Value-Belief-Norm Theory. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2022, 33, 1329–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Chung, J.E. Consumer Purchase Intention for Organic Personal Care Products. J. Consum. Mark. 2011, 28, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askadilla, W.L.; Krisjanti, M.N. Understanding Indonesian Green Consumer Behavior on Cosmetic Products: Theory of Planned Behavior Model. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 15, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, E.; Soon, P.C.; Mutum, D.S.; Nguyen, B. Health and Cosmetics: Investigating Consumers’ Values for Buying Organic Personal Care Products. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 39, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.L.; Chang, C.Y.; Yansritakul, C. Exploring Purchase Intention of Green Skincare Products Using the Theory of Planned Behavior: Testing the Moderating Effects of Country of Origin and Price Sensitivity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, J.; Jiang, B.C.; Mufidah, I.; Persada, S.F.; Noer, B.A. The Investigation of Consumers’ Behavior Intention in Using Green Skincare Products: A pro- Environmental Behavior Model Approach. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimul, A.S.; Cheah, I.; Khan, B.B. Investigating Female Shoppers’ Attitude and Purchase Intention toward Green Cosmetics in South Africa. J. Glob. Mark. 2022, 35, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arli, D.; Tan, L.P.; Tjiptono, F.; Yang, L. Exploring Consumers’ Purchase Intention towards Green Products in an Emerging Market: The Role of Consumers’ Perceived Readiness. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw, A.; Valois, P.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Using the Theory of Planned Behavior to Identify Key Beliefs Underlying Pro-Environmental Behavior in High-School Students: Implications for Educational Interventions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Madden, T.J. Prediction of Goal-Directed Behavior: Attitudes, Intentions, and Perceived Behavioral Control. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 22, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Lobo, A.; Nguyen, H.L.; Phan, T.T.H.; Cao, T.K. Determinants Influencing Conservation Behaviour: Perceptions of Vietnamese Consumers. J. Consum. Behav. 2016, 15, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D.A. Moderation. Available online: https://davidakenny.net/cm/moderation.htm (accessed on 7 February 2024).

- Zarei, A.; Maleki, F. From Decision to Run: The Moderating Role of Green Skepticism. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2018, 24, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, C.N.; Skarmeas, D. Gray Shades of Green: Causes and Consequences of Green Skepticism. J. Bus Ethics 2017, 144, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilikidou, I.; Delistavrou, A. Pro-Environmental Purchasing Behaviour during the Economic Crisis. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2014, 32, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowe, R.; Williams, S. Who Are the Ethical Consumers? The Co-operative Bank: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Young, W.; Hwang, K.; McDonald, S.; Oates, C.J. Sustainable Consumption: Green Consumer Behaviour When Purchasing Products. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleim, M.R.; Smith, J.S.; Andrews, D.; Cronin, J.J. Against the Green: A Multi-Method Examination of the Barriers to Green Consumption. J. Retail. 2013, 89, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, H.; Reid, L.N.; King, K.W. Measuring Trust In Advertising. J. Advert. 2009, 38, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osburg, V.-S.; Akhtar, P.; Yoganathan, V.; McLeay, F. The Influence of Contrasting Values on Consumer Receptiveness to Ethical Information and Ethical Choices. J. Bus Res. 2019, 104, 366–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttavuthisit, K.; Thøgersen, J. The Importance of Consumer Trust for the Emergence of a Market for Green Products: The Case of Organic Food. J. Bus Ethics 2017, 140, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Sun, Y.; Shen, J.; Xia, L. How Does Green Advertising Skepticism on Social Media Affect Consumer Intention to Purchase Green Products? J. Consum. Behav. 2020, 19, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, S.K.; Balaji, M.S. Linking Green Skepticism to Green Purchase Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 131, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, R.H.; Patel, J.D.; Acharya, N. Causality Analysis of Media Influence on Environmental Attitude, Intention and Behaviors Leading to Green Purchasing. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sama, R. Impact of Media Advertisements on Consumer Behaviour. J. Creat. Commun. 2019, 14, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A.; Iacobucci, D. Marketing Research: Methodological Foundations, 9th ed.; Thomson/South-Western: Mason, OH, USA, 2005; ISBN 9780324201604. [Google Scholar]

- Zikmund, W.C.; Babbin, B.J. Essentials of Marketing Research, 4th ed.; South-Western Cengage Learning: Mason, OH, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-324-59375-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Kuhl, J., Beckmann, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, G.A. Marketing Research: Methodological Foundations, 6th ed.; Dryden Press Series in Marketing; Dryden Press: Orlando, FL, USA, 1995; ISBN 9780030983665. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, G.A. A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.P.; Shaver, P.R.; Wrightsman, L.S. Criteria for Scale Selection and Evaluation. In Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes; Robinson, J.P., Shaver, P.R., Wrightsman, L.S., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991; pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-0-12-590241-0. [Google Scholar]

- Spector, P. Summated Rating Scale Construction; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1992; ISBN 9780803943414. [Google Scholar]

- EUROSTAT. Population on 1 January by Age, Sex and Educational Attainment Level. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/bookmark/dd48d1b9-9b11-4b5b-85c0-dabc2262fe39?lang=en (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, J.B.E.M.; Maydeu-Olivares, A. An Updated Paradigm for Evaluating Measurement Invariance Incorporating Common Method Variance and Its Assessment. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2021, 49, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odou, P.; Schill, M. How Anticipated Emotions Shape Behavioral Intentions to Fight Climate Change. J. Bus Res. 2020, 121, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelidou, N.; Hassan, L. New Advances in Attitude and Behavioural Decision-Making Models. J. Mark. Manag. 2014, 30, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| France | Germany | Greece | Spain | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Total | 503 | 100 | 570 | 100 | 308 | 100 | 453 | 100 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Men | 242 | 48.9 | 285 | 50.0 | 149 | 48.4 | 226 | 49.9 |

| Women | 261 | 51.1 | 285 | 50.0 | 159 | 51.6 | 226 | 49.9 |

| Other | 1 | 0.2 | ||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| 18–24 years old | 61 | 12.1 | 67 | 11.8 | 36 | 11.7 | 60 | 13.2 |

| 25–34 years old | 98 | 19.5 | 118 | 20.7 | 59 | 19.2 | 67 | 14.8 |

| 35–44 years old | 108 | 21.5 | 107 | 18.8 | 63 | 20.5 | 95 | 21.0 |

| 45–54 years old | 104 | 20.7 | 101 | 17.7 | 73 | 23.7 | 95 | 21.0 |

| 55–64 years old | 63 | 12.5 | 97 | 17.0 | 56 | 18.2 | 85 | 18.8 |

| 65 years or older | 68 | 13.5 | 80 | 14.0 | 21 | 6.8 | 51 | 11.3 |

| No answer | 1 | 0.2 | ||||||

| Education | ||||||||

| Primary school | 11 | 2.2 | 9 | 1.6 | 16 | 5.2 | 25 | 5.5 |

| Secondary school | 193 | 38.4 | 52 | 9.1 | 114 | 37.0 | 147 | 32.5 |

| Vocational training | 71 | 14.1 | 336 | 58.9 | 61 | 19.8 | 112 | 24.7 |

| University | 126 | 25.0 | 116 | 20.4 | 80 | 26.0 | 106 | 23.4 |

| Masters’ | 83 | 16.5 | 43 | 7.5 | 31 | 10.1 | 51 | 11.3 |

| Ph.D. | 10 | 2.0 | 9 | 1.6 | 6 | 1.9 | 12 | 2.6 |

| No answer | 9 | 1.8 | 5 | 0.9 | ||||

| Annual Income | ||||||||

| up to 5000 € | 31 | 6.2 | 23 | 4.0 | 49 | 15.9 | 21 | 4.6 |

| between 5001 €–15,000 € | 54 | 10.7 | 67 | 11.8 | 84 | 27.3 | 73 | 16.1 |

| between 15,001 €–25,000 € | 94 | 18.7 | 78 | 13.7 | 81 | 26.3 | 132 | 29.1 |

| between 25,001 €–35,000 € | 111 | 22.1 | 100 | 17.5 | 37 | 12.0 | 109 | 24.1 |

| between 35,001 €–45,000 € | 87 | 17.3 | 88 | 15.4 | 9 | 2.9 | 55 | 12.1 |

| between 45,001 €–55,001 € | 55 | 10.9 | 67 | 11.8 | 6 | 1.9 | 22 | 4.9 |

| 55,001 € and more | 40 | 8.0 | 108 | 18.9 | 2 | 0.6 | 25 | 5.5 |

| No answer | 31 | 6.2 | 39 | 6.8 | 40 | 13.0 | 16 | 3.5 |

| Occupation | ||||||||

| Professional/Entrepreneur/Farmer | 75 | 14.9 | 38 | 6.7 | 33 | 10.7 | 46 | 10.2 |

| Private employee | 103 | 20.5 | 251 | 44.0 | 99 | 32.1 | 125 | 27.8 |

| Public employee | 74 | 14.7 | 35 | 6.1 | 45 | 14.6 | 58 | 12.8 |

| Unemployed | 52 | 10.3 | 18 | 3.2 | 48 | 15.6 | 43 | 9.5 |

| Houseperson | 22 | 4.4 | 37 | 6.5 | 13 | 4.2 | 35 | 7.7 |

| Retired | 88 | 17.5 | 111 | 19.5 | 31 | 10.1 | 58 | 12.8 |

| Student | 34 | 6.8 | 32 | 5.6 | 26 | 8.4 | 49 | 10.8 |

| Other | 45 | 8.9 | 37 | 6.5 | 7 | 2.3 | 32 | 7.1 |

| No answer | 10 | 2.0 | 11 | 1.9 | 6 | 1.9 | 7 | 1.5 |

| Goodness of Fit | χ2 | df | Sig. | χ2/df | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | |

| 1855.635 | 518 | p < 0.001 | 3.582 | 0.971 | 0.974 | 0.038 | ||

| Variables/items, Range, Means, Reliability | Factor Loadings | |||||||

| Biospheric Values (BV) (range: 4–24, Mean: 19.61, α: 0.934, construct reliability: 0.934) | ||||||||

| Bio1 | Protecting the environment: preserving nature | 0.897 *** | ||||||

| Bio2 | Preventing pollution | 0.897 *** | ||||||

| Bio3 | Respecting the earth: live in harmony with other species | 0.880 *** | ||||||

| Bio4 | Unity with nature: fitting into nature | 0.856*** | ||||||

| Risk Perception 1 (RiskPer1) (range: 3–18, Mean:13.72, α: 0.914, construct reliability: 0.914) | ||||||||

| RP1 | How concerned are you about global warming? | 0.858 *** | ||||||

| RP2 | How serious of a threat do you believe global warming is to nonhuman nature? | 0.906 *** | ||||||

| RP3 | How serious are the current impacts of global warming around the world? | 0.886 *** | ||||||

| Awareness of Consequences (AC) (range; 2–12, Mean; 9.00, α: 0.813, construct reliability: 0.823) | ||||||||

| AC3 | The exhaustion of fossil fuels is a problem | 0.742 *** | ||||||

| AC4 | The exhaustion of energy sources is a problem | 0.924 *** | ||||||

| Ascription of Responsibility (AR) (range: 4–24, Mean: 16.11, α: 0.895, construct reliability: 0.898) | ||||||||

| AR1 | I am jointly responsible for CO2 emissions | 0.812 *** | ||||||

| AR2 | I feel jointly responsible for the exhaustion of energy sources | 0.889 *** | ||||||

| AR3 | I feel jointly responsible for global warming | 0.899 *** | ||||||

| AR4 | Not only the government and industry are responsible for high levels of CO2 emissions, but me too | 0.708 *** | ||||||

| Personal Norms (PN) (range: 7–42, Mean: 26.54, α: 0.936, construct reliability: 0.933) | ||||||||

| PN1 | I feel personally obliged to buy CPGs containing green chemical ingredients | 0.816 *** | ||||||

| PN2 | Regardless of what others do, I feel morally obliged to buy CPGs containing green chemical ingredients | 0.804 *** | ||||||

| PN3 | I feel guilty when I do not buy CPGs containing green chemical ingredients | 0.772 *** | ||||||

| PN4 | I feel morally obliged to use ecological products instead of regular products | 0.835 *** | ||||||

| PN5 | When I buy a new CPG, I feel a moral obligation to prefer one that contains green chemical ingredients | 0.882 *** | ||||||

| PN6 | People like me should do everything they can to buy CPGs containing green chemical ingredients | 0.843 *** | ||||||

| PN7 | I would be a better person if I consumed CPGs containing green chemical ingredients | 0.758 *** | ||||||

| Attitudes (Att) (range: 3–18, Mean: 12.76, α: 0.876, construct reliability: 0.827) | ||||||||

| At2 | Undesirable-Desirable | 0.924 *** | ||||||

| At3 | Unwise (Foolish)/Wise | 0.701 *** | ||||||

| At4 | Negative/Positive | 0.714 *** | ||||||

| Subjective Norms (SN) (range: 4–24, Mean: 14.06, α: 0.929, construct reliability: 0.929) | ||||||||

| SN1 | My family members think I should buy CPGs containing green chemical ingredients | 0.881 *** | ||||||

| SN2 | My friends think I should buy CPGs containing green chemical ingredients | 0.903 *** | ||||||

| SN3 | Important people who influence my behaviour think I should buy CPGs containing green chemical ingredients | 0.854 *** | ||||||

| SN4 | Persons who are significant to me do buy CPGs containing green chemical ingredients for themselves | 0.866 *** | ||||||

| Perceived Behavioural Control (CI) (range: 4–24, Mean: 16.10, α: 0.879, construct reliability: 0.883) | ||||||||

| PBC1 | Selecting a CPG containing green chemical ingredients is completely up to me. | 0.725 *** | ||||||

| PBC2 | I am confident that if I want to buy a CPG containing green chemical ingredients, I can buy it. | 0.878 *** | ||||||

| PBC3 | There are no obstacles for me if I want to select a CPG with green, chemical ingredients | 0.839 *** | ||||||

| PBC4 | I am confident that I can easily find a CPG containing green chemical ingredients if I want to buy it | 0.786 *** | ||||||

| Consumption Intentions (CI) (range: 4–24, Mean: 16.59, α: 0.880, construct reliability: 0.877) | ||||||||

| CI1 | I will buy CPGs containing green chemical ingredients if they are of similar quality to the regular products | 0.766 *** | ||||||

| CI2 | I will buy CPGs containing green chemical ingredients if they are of similar price to the regular products | 0.730 *** | ||||||

| CI3 | I am seriously thinking to buy CPGs containing environmentally friendlier ingredients as soon as I run out of the products I am currently using | 0.834 *** | ||||||

| CI4 | I will definitely switch to a brand of a CPG that contains green chemical ingredients | 0.868 *** | ||||||

| AVE | Correlations Squared Correlations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BV | RiskPer1 | AC | AR | PN | Att | SN | PBC | ||

| Biospheric Values (BV) | 0.779 | ||||||||

| Risk Perception (RiskPer1) | 0.781 | 0.678 *** 0.460 | |||||||

| Awareness of Consequences (AC) | 0.702 | 0.481 *** 0.231 | 0.552 *** 0.305 | ||||||

| Ascription of Responsibility (AR) | 0.690 | 0.404 *** 0.163 | 0.604 *** 0.365 | 0.443 *** 0.196 | |||||

| Personal Norms (PN) | 0.667 | 0.394 *** 0.155 | 0.552 *** 0.305 | 0.401 *** 0.161 | 0.716 *** 0.513 | ||||

| Attitudes (Att) | 0.618 | 0.396 *** 0.157 | 0.479 *** 0.229 | 0.331 *** 0.110 | 0.453 *** 0.205 | 0.539 *** 0.291 | |||

| Subjective Norms (SN) | 0.768 | 0.323 *** 0.104 | 0.425 *** 0.181 | 0.301 *** 0.091 | 0.530 *** 0.281 | 0.744 *** 0.554 | 0.539 *** 0.291 | ||

| Perceived Behav. Control (PBC) | 0.655 | 0.401 *** 0.161 | 0.456 *** 0.208 | 0.351 *** 0.123 | 0.483 *** 0.233 | 0.607 *** 0.368 | 0.477 *** 0.228 | 0.634 *** 0.402 | |

| Consumption Intentions (CI) | 0.642 | 0.465 *** 0.216 | 0.548 *** 0.300 | 0.404 *** 0.163 | 0.531 *** 0.282 | 0.722 *** 0.521 | 0.607 *** 0.368 | 0.724 *** 0.524 | 0.754 *** 0.569 |

| GOFs | Structural Models | Moderation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VBN | TPB | Combined | Scepticism | Media Influence | |||||||

| Unconstrained Model | Constrained Model | Unconstrained Model | Constrained Model | ||||||||

| χ2 | 1520.528 | 526.507 | 2901.845 | 3596.031 | 3602.362 | 3723.124 | 3729.583 | ||||

| sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| df | 242 | 80 | 541 | 1082 | 1083 | 1082 | 1083 | ||||

| χ2/df | 6.283 | 6.581 | 5.364 | 3.324 | 3.326 | 3.441 | 3.444 | ||||

| TLI | 0.959 | 0.971 | 0.950 | 0947 | 0947 | 0.943 | 0.943 | ||||

| CFI | 0.964 | 0.978 | 0.955 | 0.952 | 0.952 | 0.949 | 0.948 | ||||

| RMSEA | 0.054 | 0.055 | 0.049 | 0.036 | 0.036 | 0.037 | 0.037 | ||||

| Paths | Structural relationships (β) | Structural relationships (β) | Critical Ratios | Δχ2 test | Structural relationships (β) | Critical Ratios | Δχ2 test | ||||

| Below the Mean | Above the Mean | Below the Mean | Above the Mean | ||||||||

| BV→RiskPer1 | 0.684 *** | 0.683 *** | 0.736 *** | 0.624 *** | 0.687 *** | 0.705 *** | |||||

| RiskPer1→AC | 0.628 *** | 0.597 *** | 0.635 *** | 0.571 *** | 0.553 *** | 0.653 *** | |||||

| AC→AR | 0.541 *** | 0.382 *** | 0.427 *** | 0.358 *** | 0.343 *** | 0.452 *** | |||||

| AR→PN | 0.724 *** | 0.435 *** | 0.432 *** | 0.436 *** | 0.418 *** | 0.413 *** | |||||

| PN→CI | 0.736 *** | 0.252 *** | 0.187 *** | 0.333 *** | 0.986 | 0.299 *** | 0.165 *** | −2.640 | 6.549 | ||

| Att→CI | 0.222 *** | 0.186 *** | 0.168 *** | 0.211 *** | 0.166 | 0.194 *** | 0.140 *** | −1.200 | |||

| SN→CI | 0.318 *** | 0.185 *** | 0.205 *** | 0.159 *** | −1.780 | 0.186 *** | 0.210 *** | 0.190 | |||

| PBC→CI | 0.444 *** | 0.407 *** | 0.460 *** | 0.340 *** | −2.603 | 6.331 | 0.369 *** | 0.487 *** | 1.832 | ||

| SN→AR | 0.450 *** | 0.324 *** | 0.544 *** | 0.412 *** | 0.480 *** | ||||||

| SN→PN | 0.535 *** | 0.537 *** | 0.539 *** | 0.541 *** | 0.501 *** | ||||||

| Squared Multiple Correlations (R2) | 0.541 | 0.697 | 0.711 | 0.703 | 0.726 | 0.696 | 0.725 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Delistavrou, A.; Tilikidou, I. Recycled CO2 in Consumer Packaged Goods: Combining Values and Attitudes to Examine Europeans’ Consumption Intentions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3515. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083515

Delistavrou A, Tilikidou I. Recycled CO2 in Consumer Packaged Goods: Combining Values and Attitudes to Examine Europeans’ Consumption Intentions. Sustainability. 2025; 17(8):3515. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083515

Chicago/Turabian StyleDelistavrou, Antonia, and Irene Tilikidou. 2025. "Recycled CO2 in Consumer Packaged Goods: Combining Values and Attitudes to Examine Europeans’ Consumption Intentions" Sustainability 17, no. 8: 3515. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083515

APA StyleDelistavrou, A., & Tilikidou, I. (2025). Recycled CO2 in Consumer Packaged Goods: Combining Values and Attitudes to Examine Europeans’ Consumption Intentions. Sustainability, 17(8), 3515. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083515