How Does Environmental Sustainability Commitment Affect Corporate Environmental Performance: A Chain Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

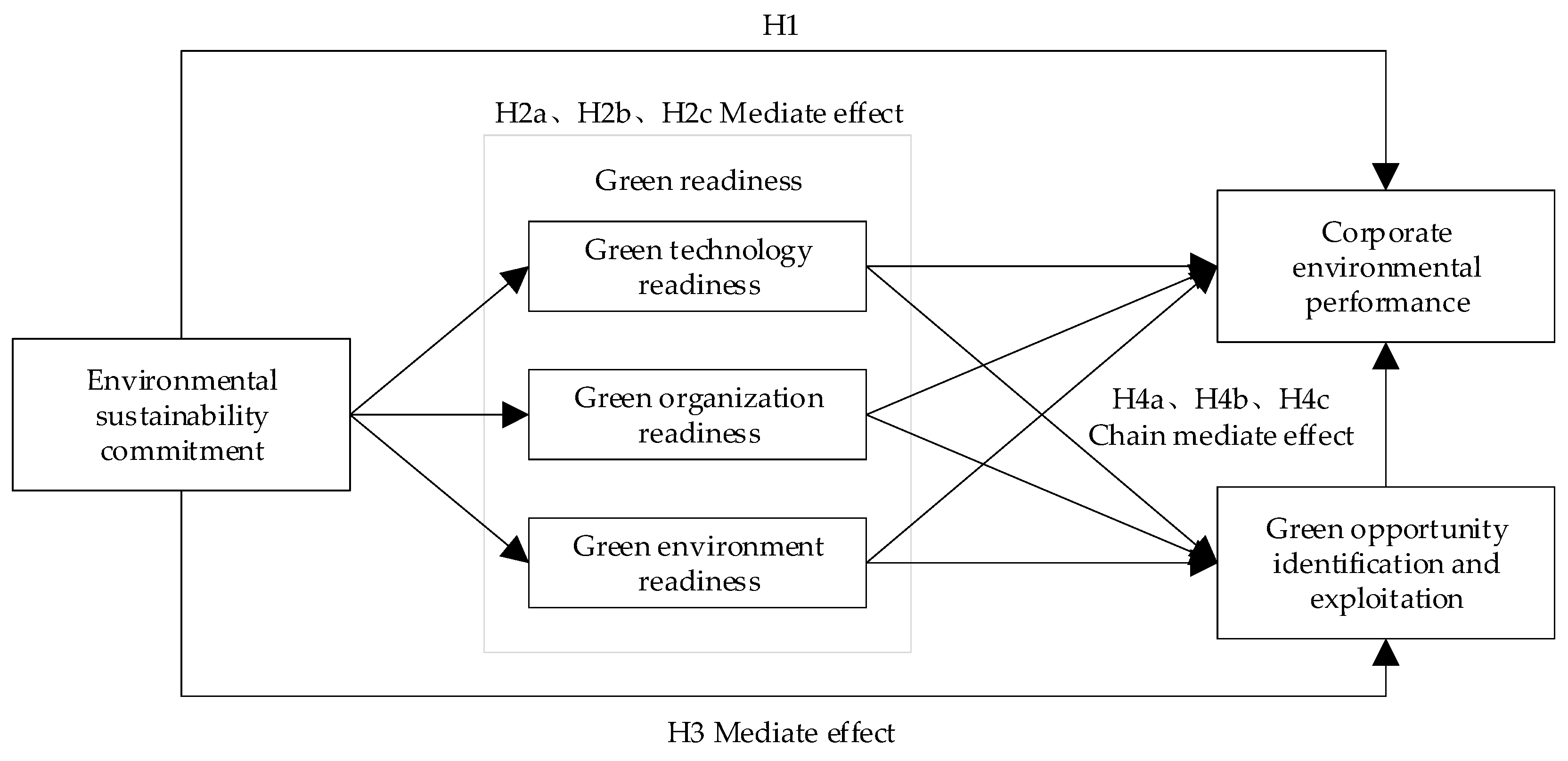

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Environmental Sustainability Commitment and Corporate Environmental Performance

2.2. The Mediating Role of Green Readiness

2.3. The Mediating Role of Green Opportunity Identification and Exploitation

2.4. The Chain Mediating Role of Green Readiness and Green Opportunity Identification and Exploitation

3. Methods

3.1. Sample

3.2. Measures

| Construct and Derivation | Indicator | Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Corporate environmental performance (CEP), Sahoo et al. (2023) [69] | CEP1 CEP2 CEP3 CEP4 CEP5 | We can promote the reduction of air emissions. We can promote the reduction of wastewater. We can promote the reduction of solid wastes. We can decrease the consumption of hazardous/ harmful/toxic materials. We can improve the company’s environmental situation. |

| Environmental sustainability commitment (ESC), Rehman et al. (2022) [33] | ESC1 ESC2 ESC3 ESC4 | Environmental protection is part of the business. Committing to environmental sustainability is good for my business. Our commitment to the environment allows us to gain more customers. We are proud to do business in the local community. |

| Green technology readiness (GTR), Zhang et al. (2020) [41] | GTR1 GTR2 GTR3 GTR4 GTR5 | Our green technologies meet our operational needs. Our green technologies match the requirements of suppliers/customers. Our green technologies increase operational efficiency. Our green technologies promote job effectiveness. Our green technologies enhance product/service quality. |

| Green organization readiness (GOR), Zhang et al. (2020) [41] | GOR1 GOR2 GOR3 GOR4 GOR5 GOR6 | Our organization cultivates a green culture among employees. Our organization pays attention to environmental protection in daily operations. Our organization incorporates sustainable development in corporate strategy. Our organization encourages employees to think creatively. Our organization provides managerial support at all levels. Our organization makes resources available as possible. |

| Green environment readiness (GER), Zhang et al. (2020) [41] | GER1 GER2 GER3 GER4 GER5 | Our organization pays attention to and complies with environmental policies. Our organization shares policy updates with employees. Our organization keeps track of green product/service demands. Our organization understands customers’ environmental concerns. Our organization regards customers as environmental partners. |

| Green opportunities identification and exploitation (GOIE), Ozgen et al. (2007) [67] and Dewar and Dutton (1986) [68] | GOIE1 GOIE2 GOIE3 GOIE4 GOIE5 GOIE6 | Our company can gather green opportunity information quickly. Our company can identify the impact of new information quickly. Our company can master new green opportunity information. Our company can master new green opportunity information. Our company can provide new green products/services. Our company can provide new green products/services. |

3.3. Evaluation of Common Method Bias

4. Results

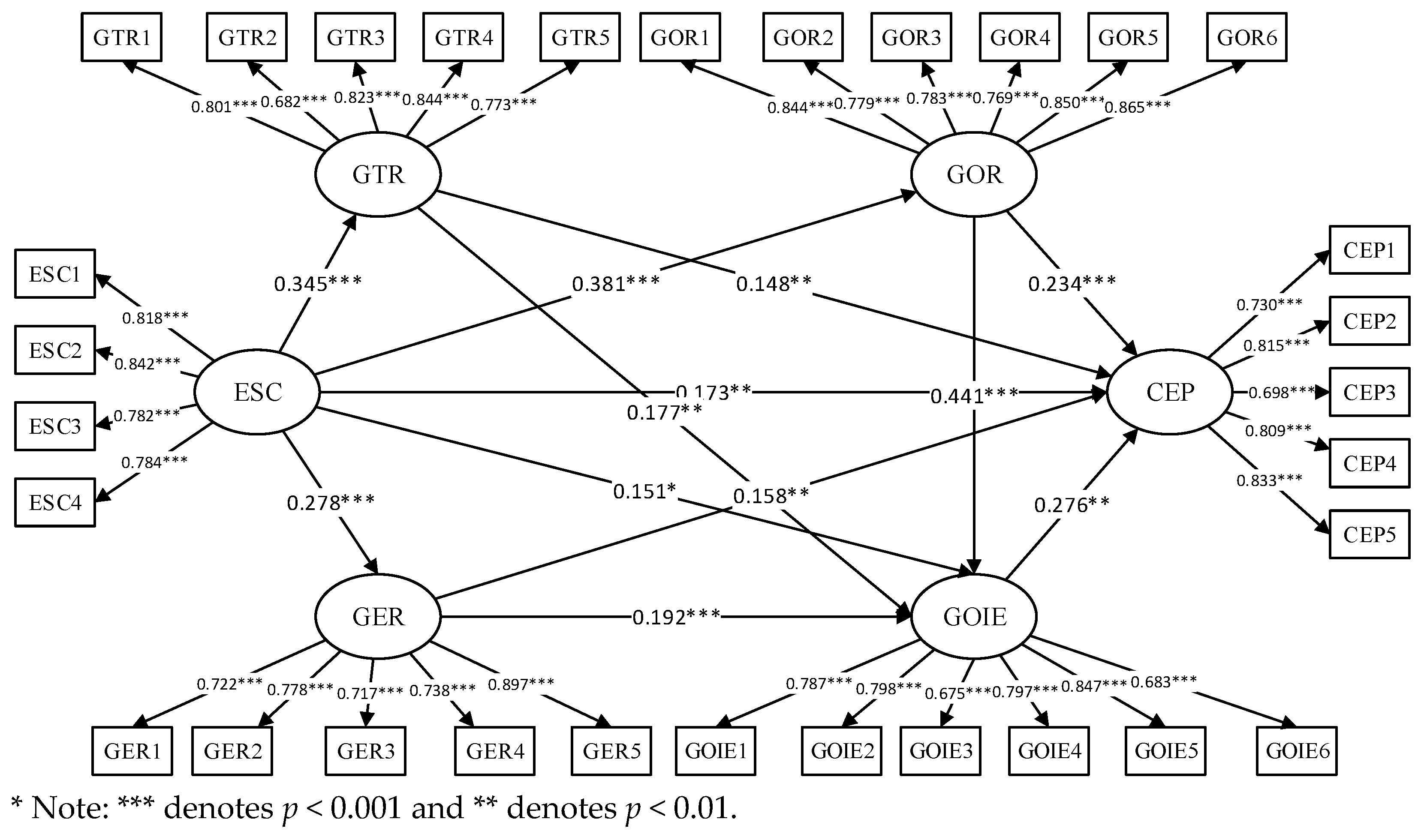

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

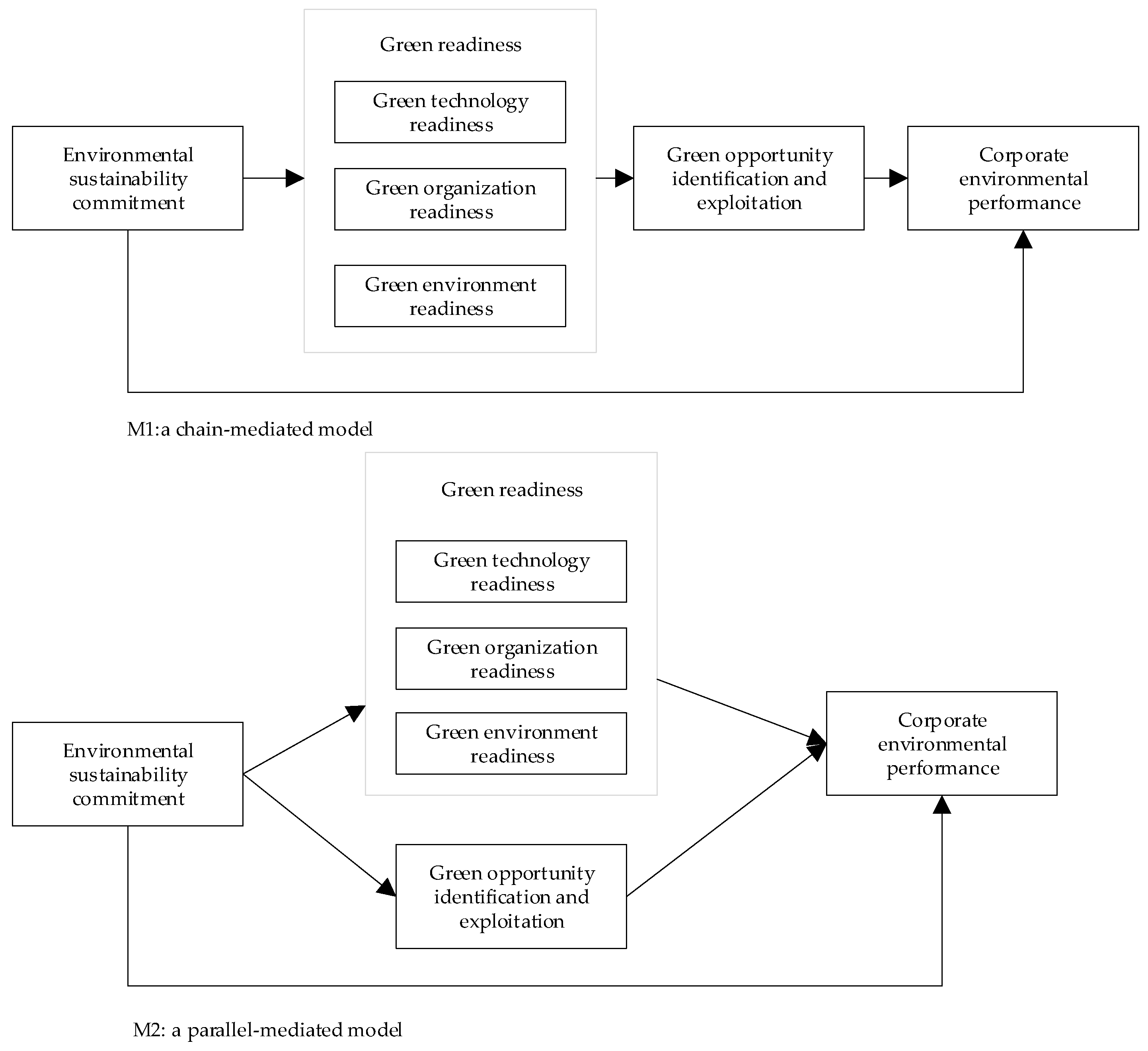

4.2. Model Selection

4.3. Hypotheses Testing

4.4. Robustness Tests

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Managerial Implications

5.4. Limits and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chan, R.Y.K.; He, H.; Chan, H.K.; Wang, W.Y.C. Environmental Orientation and Corporate Performance: The Mediation Mechanism of Green Supply Chain Management and Moderating Effect of Competitive Intensity. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2012, 41, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.B.; Iyer, E.S.; Kashyap, R.K. Corporate Environmentalism: Antecedents and Influence of Industry Type. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, A.; Menon, A. Enviropreneurial Marketing Strategy: The Emergence of Corporate Environmentalism as Market Strategy. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekasari, K.; Eltivia, N.; Indrawan, A.K.; Miharso, A. Corporate Commitment of Environment: Evidence from Sustainability Reports of Mining Companies in Indonesia. Indones. J. Sustain. Account. Manag. 2021, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Burbano, V.C. The Drivers of Greenwashing. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 54, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras-Saizarbitoria, I.; Boiral, O.; Díaz De Junguitu, A. Environmental Management Certification and Environmental Performance: Greening or Greenwashing? Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 2829–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Boiral, O.; Iraldo, F. Internalization of Environmental Practices and Institutional Complexity: Can Stakeholders Pressures Encourage Greenwashing? J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 147, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudłak, R. Greenwashing or Striving to Persist: An Alternative Explanation of a Loose Coupling between Corporate Environmental Commitments and Outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics 2025, 197, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahdi, K.S.; Acikdilli, G. Marketing Communications and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): Marriage of Convenience or Shotgun Wedding? J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Montes-Sancho, M.J. Voluntary Agreements to Improve Environmental Quality: Symbolic and Substantive Cooperation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 575–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Umrani, W.A. Corporate Social Responsibility and Pro-Environmental Behavior at Workplace: The Role of Moral Reflectiveness, Coworker Advocacy, and Environmental Commitment. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cop, S.; Alola, U.V.; Alola, A.A. Perceived Behavioral Control as a Mediator of Hotels’ Green Training, Environmental Commitment, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Sustainable Environmental Practice. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 3495–3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Reynolds, D. Predicting Green Hotel Behavioral Intentions Using a Theory of Environmental Commitment and Sacrifice for the Environment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 52, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibattista, I.; Berdicchia, D.; Mazzardo, E.; Masino, G. Green Norms in the Workplace to Promote Environmental Sustainability: The Positive Effect on Green Innovative Work Behaviors and Person-Environment Relationship. Front. Sustain. 2025, 5, 1506804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tang, G.; Jin, J.; Li, J.; Paillé, P. Linking Market Orientation and Environmental Performance: The Influence of Environmental Strategy, Employee’s Environmental Involvement, and Environmental Product Quality. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 479–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Raghupathi, W.; Raghupathi, V. An Exploratory Study of the Association between Green Bond Features and ESG Performance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarboui, A.; Bouzouitina, A. How Do the CEO Demographic Characteristics Affect CSR Commitment in European Firms? Soc. Bus. Rev. 2025. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardberg, N.A.; Fombrun, C.J. Corporate Citizenship: Creating Intangible Assets across Institutional Environments. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, J. The Synergy Impact of External Environmental Pressures and Corporate Environmental Commitment on Innovations in Green Technology. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 854–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Tung, A.; Baird, K. The Influence of Environmental Commitment on the Take-up of Environmental Management Initiatives. Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, I.; Sadorsky, P. The Relationship between Environmental Commitment and Managerial Perceptions of Stakeholder Importance. AMJ 1999, 42, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kärnä, J.; Hansen, E.; Juslin, H. Social Responsibility in Environmental Marketing Planning. Eur. J. Mark. 2003, 37, 848–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.-J.; Thérin, F. Knowledge Acquisition and Environmental Commitment in SMEs. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, K. Frontiers in Group Dynamics: Concept, Method and Reality in Social Science; Social Equilibria and Social Change. Hum. Relat. 1947, 1, 5–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zhao, M.; Ren, J. The Influence Mechanism of Corporate Environmental Responsibility on Corporate Performance: The Mediation Effect of Green Innovation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Choubey, A. Green Banking Initiatives: A Qualitative Study on Indian Banking Sector. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, N.; Rigoni, U.; Orij, R.P. Corporate Governance and Sustainability Performance: Analysis of Triple Bottom Line Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Lai, S.-B.; Wen, C.-T. The Influence of Green Innovation Performance on Corporate Advantage in Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojnik, J.; Ruzzier, M. What Drives Eco-Innovation? A Review of an Emerging Literature. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2016, 19, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. A Natural-Resource-Based View of the Firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.U.; Bresciani, S.; Yahiaoui, D.; Giacosa, E. Environmental Sustainability Orientation and Corporate Social Responsibility Influence on Environmental Performance of Small and Medium Enterprises: The Mediating Effect of Green Capability. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1954–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, D.; Power, D.; Samson, D. Greening the Automotive Supply Chain: A Relationship Perspective. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2007, 27, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Li, S.; Capaldo, A. Green Supply Chain Management, Supplier Environmental Commitment, and the Roles of Supplier Perceived Relationship Attractiveness and Justice. A Moderated Moderation Analysis. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 3523–3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J.; Nilsson, J.; Modig, F.; Hed Vall, G. Commitment to Sustainability in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: The Influence of Strategic Orientations and Management Values. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2017, 26, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.L.; Green, J.D.; Reed, A. Interdependence with the Environment: Commitment, Interconnectedness, and Environmental Behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.D.; Brooks, G.R.; Goes, J.B. Environmental Jolts and Industry Revolutions: Organizational Responses to Discontinuous Change. Strateg. Manag. J. 1990, 11, 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Wang, H. Traditional Energy and Renewable Energy: The Differences and Transitions. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Public Art and Human Development ( ICPAHD 2021); Kunming, China, 24–26 December 2021, Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 1100–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, H.; Date, H.; Raoot, A.D. Review on IT Adoption: Insights from Recent Technologies. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2014, 27, 488–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y. Critical Success Factors of Green Innovation: Technology, Organization and Environment Readiness. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 264, 121701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Rehman, S.U.; García, F.J.S. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Performance: The Mediating Role of Environmental Strategy and Green Innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 160, 120262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GRACI, S.; DODDS, R. Why Go Green? The Business Case for Environmental Commitment in the Canadian Hotel Industry. Anatolia 2008, 19, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.-J.; Boiral, O.; Lagacé, D. Environmental Commitment and Manufacturing Excellence: A Comparative Study within Canadian Industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2001, 10, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Pujari, D.; Pontrandolfo, P. Green Product Innovation in Manufacturing Firms: A Sustainability-Oriented Dynamic Capability Perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 490–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallaster, C. Managing a Company Crisis through Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility: A Practice-Based Analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, S.T.; Iqbal, K. How Does Green Human Resource Management Foster Employees’ Environmental Commitment: A Sequential Mediation Analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malokani, D.K.A.K.; Mumtaz, S.N.; Junejo, D.; Shaikh, D.H.; Hassan, N.; Darazi, M.A.; Malokani, M. The Green HRM Impact on Employees’ Environmental Commitment: Mediating Effect of Organizational Pride. Metall. Mater. Eng. 2024, 30, 470–480. [Google Scholar]

- Barron, A.; Hultén, P.; Vanyushyn, V. Country-of-Origin Effects on Managers’ Environmental Scanning Behaviours: Evidence from the Political Crisis in the Eurozone. Environ. Plann C Gov. Policy 2015, 33, 601–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirunyawipada, T.; Xiong, G. Corporate Environmental Commitment and Financial Performance: Moderating Effects of Marketing and Operations Capabilities. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 86, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roome, N.; Wijen, F. Stakeholder Power and Organizational Learning in Corporate Environmental Management. Organ. Stud. 2006, 27, 235–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Zhang, S.; Peng, J. The Value of Marketing Innovation: Market-Driven versus Market-Driving. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 126, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castka, P.; Balzarova, M.A.; Bamber, C.J.; Sharp, J.M. How Can SMEs Effectively Implement the CSR Agenda? A UK Case Study Perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2004, 11, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadenne, D.L.; Kennedy, J.; McKeiver, C. An Empirical Study of Environmental Awareness and Practices in SMEs. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhadi, A.; Kamble, S.S.; Zkik, K.; Cherrafi, A.; Touriki, F.E. The Integrated Effect of Big Data Analytics, Lean Six Sigma and Green Manufacturing on the Environmental Performance of Manufacturing Companies: The Case of North Africa. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, P. The Discipline of Innovation. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1985, 63, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.R.; Lévesque, M.; Shepherd, D.A. When Should Entrepreneurs Expedite or Delay Opportunity Exploitation? J. Bus. Ventur. 2008, 23, 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeffane, R.M.; Polonsky, M.J.; Medley, P. Corporate Environmental Commitment: Developing the Operational Concept. Bus. Strategy Environ. 1994, 3, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Venkataraman, S. The Promise of Entrepreneurship as a Field of Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, N.J.; Lyngsie, J.; Zahra, S.A. The Role of External Knowledge Sources and Organizational Design in the Process of Opportunity Exploitation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 1453–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Patzelt, H.; Baron, R.A. “I Care about Nature, but …”: Disengaging Values in Assessing Opportunities That Cause Harm. AMJ 2013, 56, 1251–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, P.; O’Brien, J.P.; Yoshikawa, T. The Implications of Debt Heterogeneity for R&D Investment and Firm Performance. AMJ 2008, 51, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, J.T.; Shane, S.A. Opportunities and Entrepreneurship. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, R.R.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, F.; Fang, K. Multi-Objective Energy Planning for China’s Dual Carbon Goals. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 34, 552–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, A.; Wu, Y. Environmental Regulation and Green Innovation: Evidence from China’s New Environmental Protection Law. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkin, T.R. A Review of Scale Development Practices in the Study of Organizations. J. Manag. 1995, 21, 967–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozgen, E.; Baron, R.A. Social Sources of Information in Opportunity Recognition: Effects of Mentors, Industry Networks, and Professional Forums. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 174–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewar, R.D.; Dutton, J.E. The Adoption of Radical and Incremental Innovations: An Empirical Analysis. Manag. Sci. 1986, 32, 1422–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Kumar, A.; Upadhyay, A. How Do Green Knowledge Management and Green Technology Innovation Impact Corporate Environmental Performance? Understanding the Role of Green Knowledge Acquisition. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error—Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Descriptive Items | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Firm size (employees) | ||

| Less than 50 | 31 | 9.57% |

| 51–100 | 34 | 10.49% |

| 101–500 | 69 | 21.30% |

| 501–1000 | 53 | 16.36% |

| Above 1000 | 137 | 42.28% |

| Industry type | ||

| Manufacturing | 148 | 45.68% |

| Construction | 29 | 8.95% |

| Transportation and Logistics | 17 | 5.25% |

| Information Technology | 51 | 15.74% |

| Retail and Wholesale Trade | 17 | 5.25% |

| Financial Services | 20 | 6.17% |

| Others | 42 | 12.96% |

| Firm age (years) | ||

| Less than 3 | 41 | 12.65% |

| 3–5 | 63 | 19.44% |

| 5–10 | 72 | 22.22% |

| 10–15 | 89 | 27.47% |

| More than 15 | 59 | 18.21% |

| Working experience (years) | ||

| Less than 3 | 22 | 6.79% |

| 3–5 | 44 | 13.58% |

| 5–10 | 77 | 23.77% |

| 10–15 | 92 | 28.40% |

| More than 15 | 89 | 27.47% |

| Variables | Items | Loading | KMO | Cronbach’s Alpha | C.R. | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEP | CEP1 CEP2 CEP3 CEP4 CEP5 | 0.753 0.832 0.722 0.827 0.850 | 0.885 | 0.895 | 0.897 | 0.637 |

| ESC | ESC1 ESC2 ESC3 ESC4 | 0.820 0.845 0.785 0.788 | 0.837 | 0.884 | 0.884 | 0.656 |

| GTR | GTR1 GTR2 GTR3 GTR4 GTR5 | 0.805 0.684 0.831 0.833 0.771 | 0.875 | 0.888 | 0.890 | 0.619 |

| GOR | GOR1 GOR2 GOR3 GOR4 GOR5 GOR6 | 0.843 0.784 0.786 0.769 0.850 0.861 | 0.917 | 0.922 | 0.923 | 0.666 |

| GER | GER1 GER2 GER3 GER4 GER5 | 0.728 0.781 0.718 0.734 0.893 | 0.841 | 0.879 | 0.881 | 0.598 |

| GOIE | GOIE1 GOIE2 GOIE3 GOIE4 GOIE5 GOIE6 | 0.808 0.818 0.700 0.816 0.863 0.708 | 0.908 | 0.907 | 0.907 | 0.621 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fornell and Larcker criterion | ||||||

| 1.CEP | 0.798 | |||||

| 2.ESC | 0.417 *** | 0.810 | ||||

| 3.GTR | 0.552 *** | 0.301 *** | 0.787 | |||

| 4.GOR | 0.608 *** | 0.344 *** | 0.571 *** | 0.816 | ||

| 5.GER | 0.542 *** | 0.226 *** | 0.671 *** | 0.575 *** | 0.773 | |

| 6.GOIE | 0.626 *** | 0.375 *** | 0.542*** | 0.644 *** | 0.537 *** | 0.788 |

| Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio criterion | ||||||

| 1.CEP | ||||||

| 2.ESC | 0.424 | |||||

| 3.GTR | 0.564 | 0.304 | ||||

| 4.GOR | 0.620 | 0.352 | 0.586 | |||

| 5.GER | 0.544 | 0.222 | 0.671 | 0.588 | ||

| 6.GOIE | 0.617 | 0.371 | 0.537 | 0.639 | 0.521 | |

| Model | χ2/d.f. | GFI | CFI | NNFI | IFI | PNFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M0 | 2.273 | 0.844 | 0.920 | 0.911 | 0.920 | 0.786 | 0.063 |

| M1 | 2.352 | 0.834 | 0.914 | 0.906 | 0.914 | 0.788 | 0.065 |

| M2 | 2.555 | 0.815 | 0.901 | 0.892 | 0.902 | 0.775 | 0.069 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Coefficient | S.E. | C.R. | p | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | ESC→CEP | 0.173 | 0.051 | 2.796 | 0.005 | Supported |

| Hypothesis | Path | Coefficient | S.E. | p | LLCI | ULCI | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2a | ESC→GTR→CEP | 0.051 | 0.030 | 0.038 | 0.003 | 0.124 | Supported |

| H2b | ESC→GOR→CEP | 0.089 | 0.039 | 0.003 | 0.031 | 0.186 | Supported |

| H2c | ESC→GER→CEP | 0.044 | 0.028 | 0.029 | 0.004 | 0.117 | Supported |

| H3 | ESC→GOIE→CEP | 0.042 | 0.025 | 0.018 | 0.007 | 0.107 | Supported |

| H4a | ESC→GTR→GOIE→CEP | 0.017 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.002 | 0.053 | Supported |

| H4b | ESC→GOR→GOIE→CEP | 0.046 | 0.020 | 0.000 | 0.019 | 0.106 | Supported |

| H4c | ESC→GER→GOIE→CEP | 0.015 | 0.010 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.046 | Supported |

| Paths | Estimate | S.E. | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESC—CEP | 0.375 | 0.051 | 0.268 | 0.468 |

| ESC—GTR—CEP | 0.075 | 0.026 | 0.031 | 0.129 |

| ESC—GOR—CEP | 0.103 | 0.032 | 0.049 | 0.173 |

| ESC—GER—CEP | 0.053 | 0.022 | 0.016 | 0.101 |

| ESC—GOIE—CEP | 0.162 | 0.039 | 0.093 | 0.246 |

| ESC—GTR—GOIE—CEP | 0.041 | 0.014 | 0.018 | 0.073 |

| ESC—GOR—GOIE—CEP | 0.053 | 0.018 | 0.024 | 0.092 |

| ESC—GER—GOIE—CEP | 0.029 | 0.013 | 0.009 | 0.058 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Shao, X.; Sun, T. How Does Environmental Sustainability Commitment Affect Corporate Environmental Performance: A Chain Mediation Model. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3461. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083461

Zhang J, Shao X, Sun T. How Does Environmental Sustainability Commitment Affect Corporate Environmental Performance: A Chain Mediation Model. Sustainability. 2025; 17(8):3461. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083461

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jinshan, Xuan Shao, and Tingshu Sun. 2025. "How Does Environmental Sustainability Commitment Affect Corporate Environmental Performance: A Chain Mediation Model" Sustainability 17, no. 8: 3461. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083461

APA StyleZhang, J., Shao, X., & Sun, T. (2025). How Does Environmental Sustainability Commitment Affect Corporate Environmental Performance: A Chain Mediation Model. Sustainability, 17(8), 3461. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083461