Research on the Evolutionary Game of Quality Governance of Geographical Indication Agricultural Products in China: From the Perspective of Industry Self-Governance

Abstract

1. Introduction

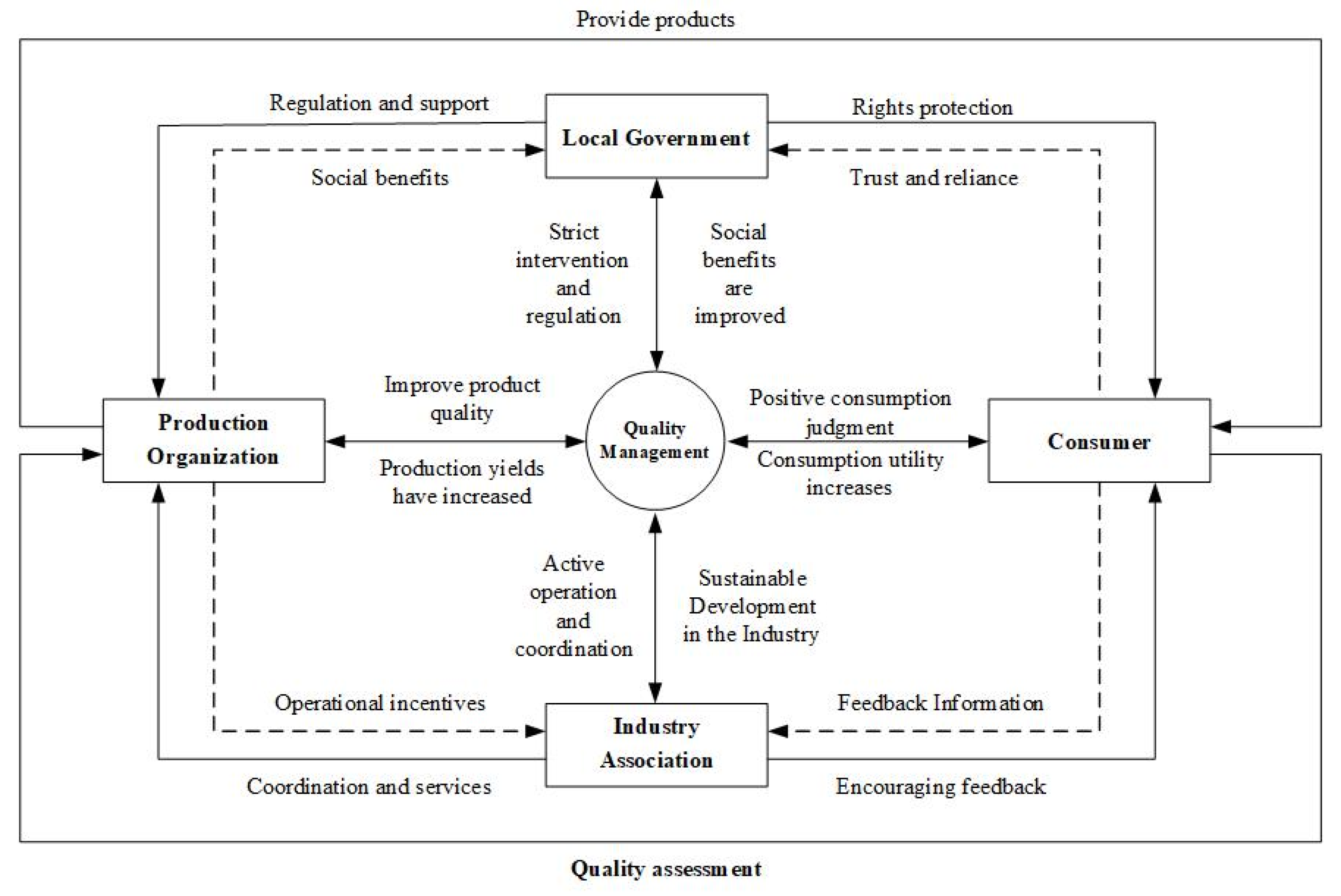

2. Model Assumptions and Construction

2.1. Model Assumptions

2.2. Model Building and Solution

- (1)

- The replication dynamic equation of agricultural product production organizations

- (2)

- The replication dynamic equation of local governments

- (3)

- The replication dynamic equation of industry associations

- (4)

- The replication dynamic equation of Consumer

3. Analysis of the Stability of Equilibrium Points in the Four-Dimensional Evolutionary Game System

3.1. Analysis of the Stability of Strategic Combination Under the Passive Compliance of Industry Associations

3.2. Analysis of the Stability of Strategic Portfolios Under the Active Responsibility of Industry Associations

4. Simulation Analysis

4.1. Parameter Assignment

- (1)

- According to the survey data on the production and consumption of “Three Standards and One Brand” released by the Suzhou Municipal Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Affairs [39], the additional cost for most production organizations adopting standardized production is typically 20% to 50% higher than that of conventional production. Taking the median value of 35%, and considering that the premium level for most geographical indications ranges from 20% to 50%, combined with the research by Jiang et al. (2023) on the premium of agricultural product geographical indications [40], the premium level for agricultural product geographical indications is approximately 32%. Therefore, in this study, the premium level is set at 32%, with set at 15 and at 21. According to the “ Measures for the Protection of Geographical Indications Products” [41], and the “Product Quality Law of the People’s Republic of China” [42], individuals or entities forging or misappropriating certification marks will have their illegal products confiscated and be fined an amount not exceeding the value of the goods. Based on publicly available administrative penalty information from Jining City, Shandong Province, is set at 4. Additionally, according to the “Food Safety Law” of China [43], consumers can demand that producers pay ten times the price or three times the loss for producing food that does not meet standards. Combined with the research by Huo & Liu (2024) on the supervision of agricultural product quality and safety [44], is set at 1.5. Drawing on the research by Wu et al. and Xia et al. [45,46], , , , and are, respectively, set at 2, 3, 1.2, 1.1, 1, and 4;

- (2)

- Based on the research by Guo et al. (2023) regarding government intervention in the development of agricultural product brands [47], and in conjunction with the 2024 budget data from the Ganzhou Municipal Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Affairs [48], the values of and are set at 8 and 10, respectively. Given that the current tax rate imposed by the Chinese government on agricultural products is 9%, is set to 2. Drawing on the accountability scenarios for local governments in product quality supervision as outlined in the study by Zhao et al. (2023) [49], is assigned a value of 4. Furthermore, concerning the success probabilities of supervision conducted by local governments and industry associations, this paper references the research by Wu et al. (2024) on quality investment behavior in the food supply chain under the framework of social co-governance [45], setting , and to 0.4, 0.5, and 0.7, respectively;

- (3)

- Referring to the charter of the Ganzhou City Gan Nan Tangerine Industry Association [50], the cost of fulfilling the association’s duties includes expenses for skills training and supervision. Based on the research by Li et al. (2022) [19], is set at 6. According to Qi et al. (2009)’s study on the role of industry associations in agricultural industrialization [51], is set at 5, while , and are assigned values of 3, 2, and 0.2, respectively. Drawing on the budget data from the Ganzhou City Agricultural and Rural Affairs Bureau for 2024, which allocates 70,000 yuan for rural cooperative economies, and combining this with the notice issued by the Ministry of Finance in 2018 [52], as well as Lyu (2015) ’s research [53], local governments support association development through service procurement and other means and provide rewards to entities obtaining geographical indication product status. Therefore, is set at 4. Referring to the trust crisis triggered by the inaction of the “Northeast Rice” association, the failure of industry associations to act can lead to reputation losses (e.g., member attrition). Hence, is set at 3;

- (4)

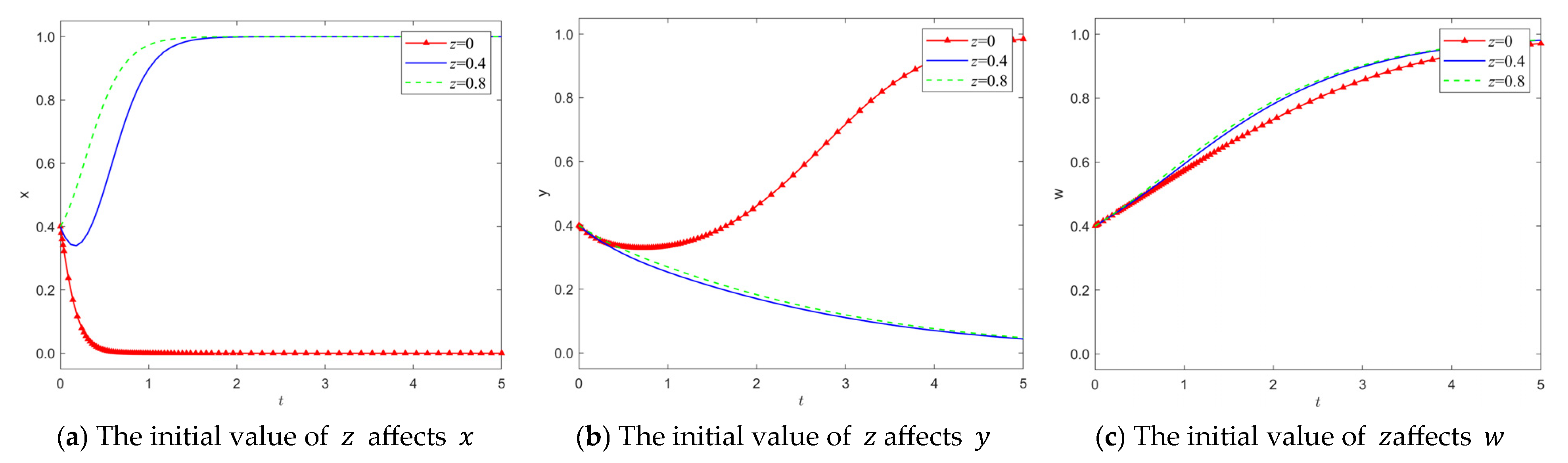

4.2. Numerical Analysis of the Stability of the Ideal Equilibrium Point

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Parameters

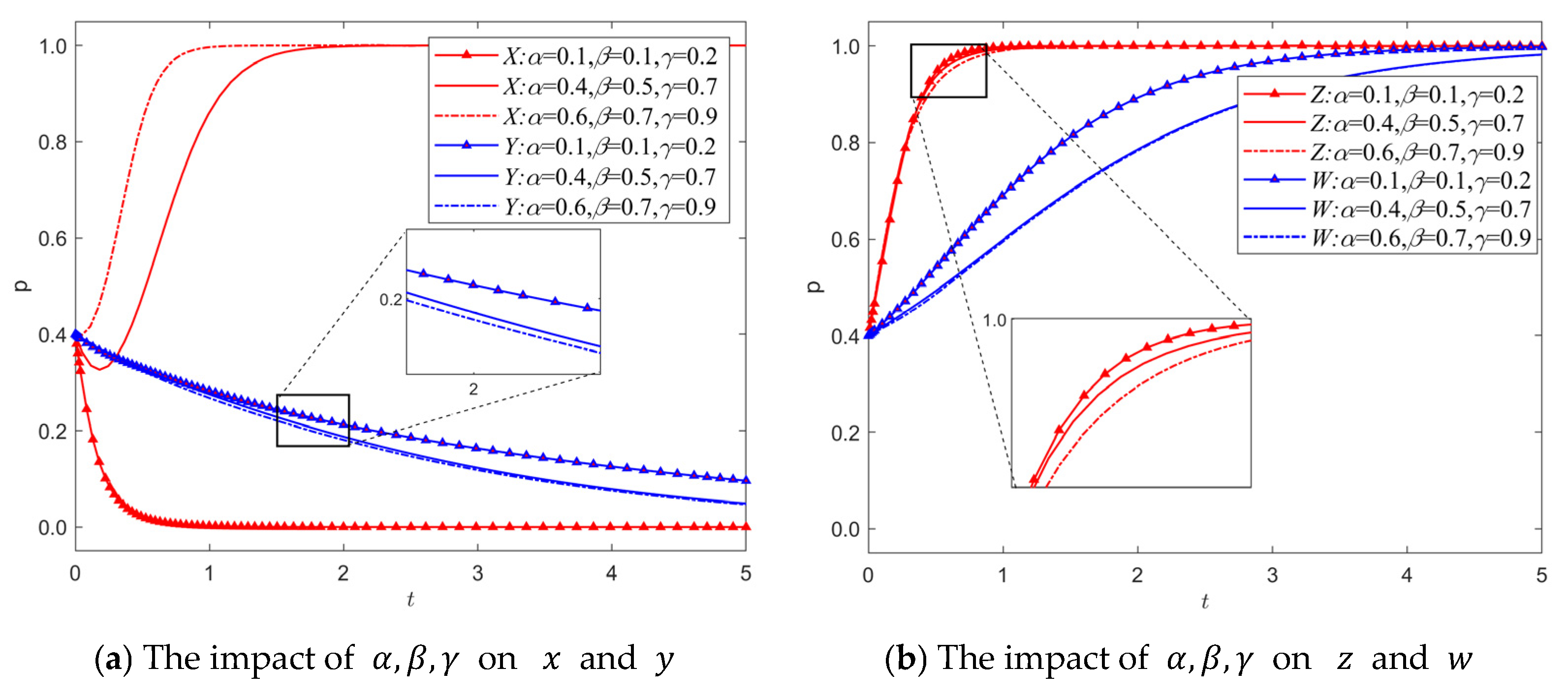

- (1)

- The impact of industry self-regulation mechanisms on evolution

- (2)

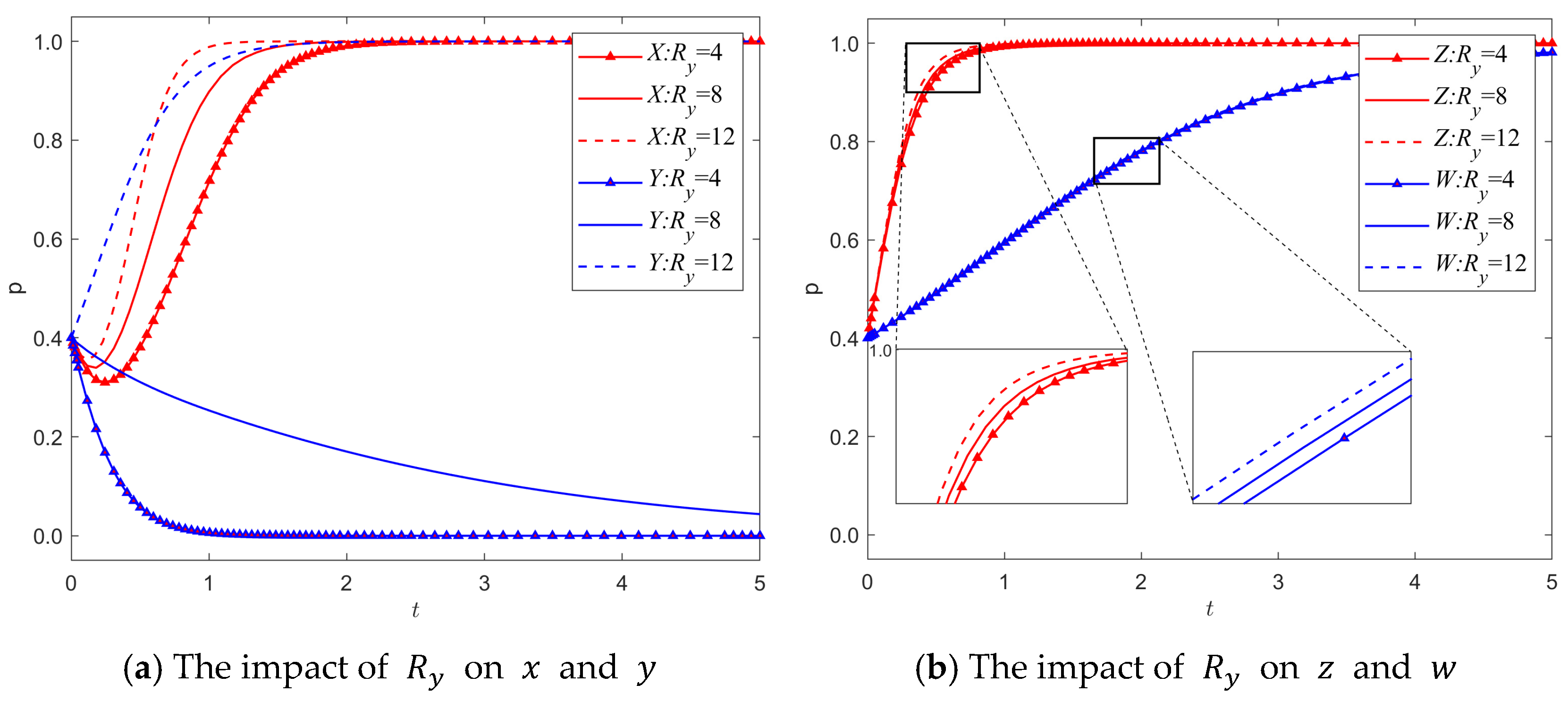

- The synergistic capabilities of industry associations in influencing evolution

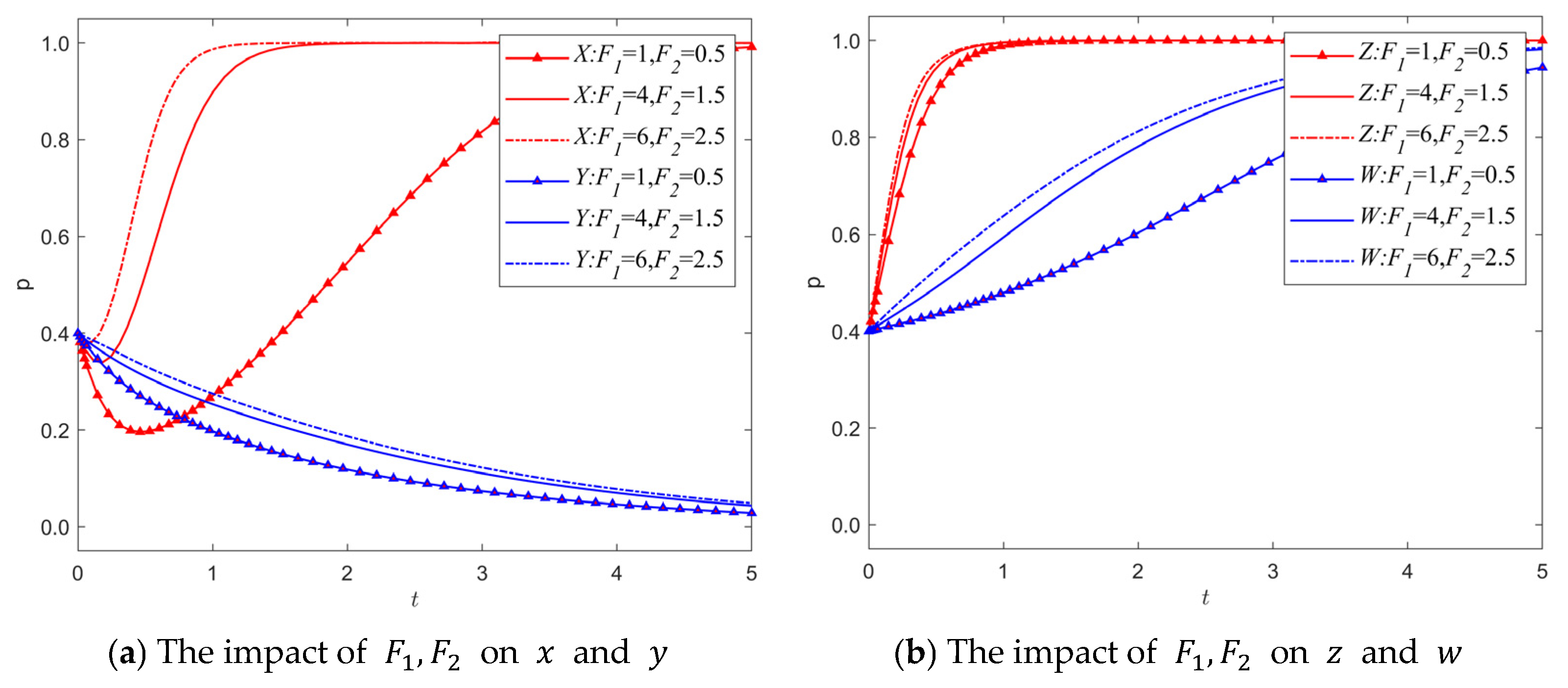

- (3)

- The impact of subsidies and benefit distribution on evolution

- (4)

- The impact of reputation mechanisms on evolution

- (5)

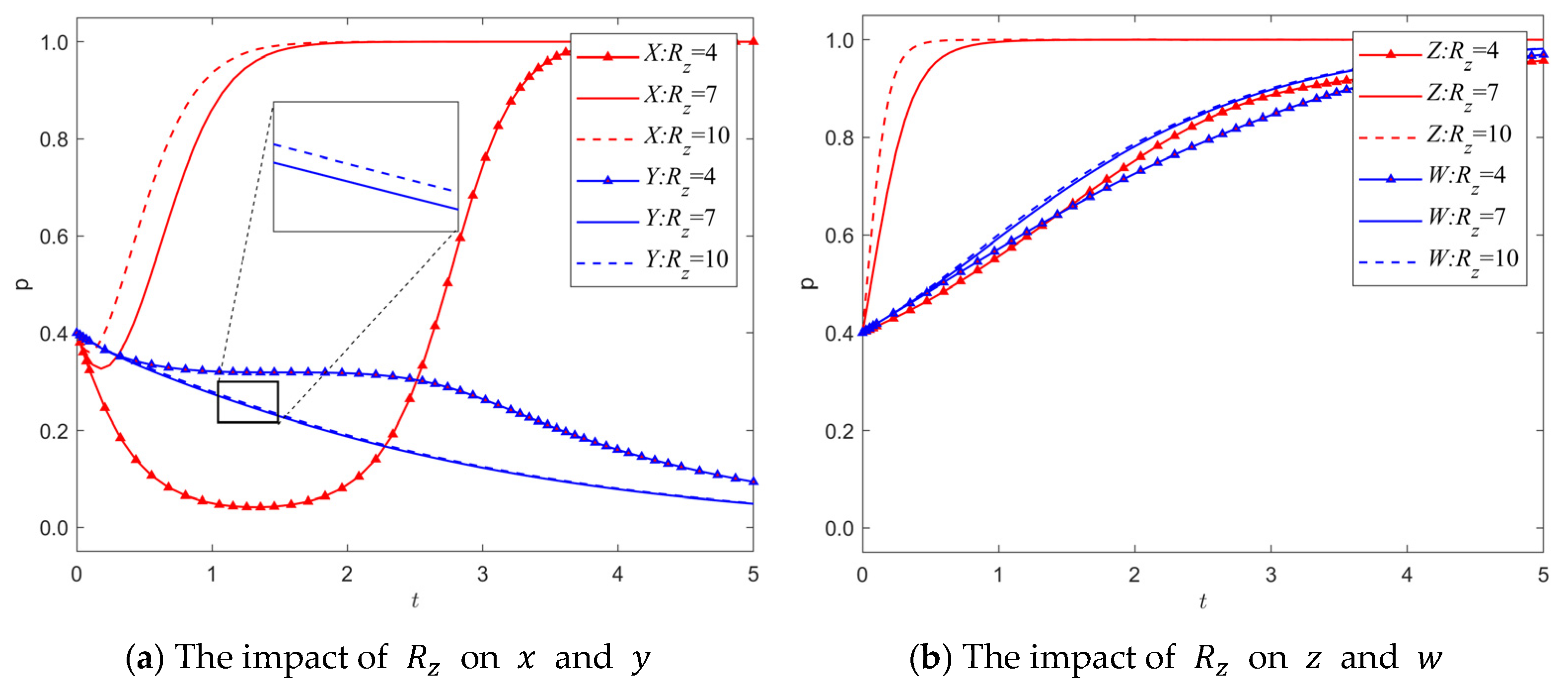

- The impact of regulation on evolution

- (6)

- The impact of consumer participation costs and benefits on evolution

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- The game model constructed in this paper has a series of stable equilibrium points in the two distinct stages of geographical indication industry development. (1,1,1,1) is the ideal equilibrium point in the initial stage of development, where the production organization conducts autonomous production, the local government exercises strict regulation, the industry association actively fulfills its responsibilities, and the consumer participates in governance. (1,0,1,1) is the ideal equilibrium point in the mature stage of development, where the production organization conducts autonomous production, the local government loosens its regulation, the industry association actively fulfills its responsibilities, and the consumer participates in governance. This indicates that the optimal regulatory strategy of local governments can be adjusted in accordance with the different stages of industrial development under industry self-governance;

- (2)

- The industry self-regulation mechanism proves to be effective and highly efficient. The strategy choices of industry associations exert significant influences on the strategic decisions of other stakeholders. The support from local governments, donations from social organizations, social reputation, and the ability to integrate resources are the key factors motivating industry associations to actively fulfill their responsibilities. The resource integration capacity of industry associations can effectively drive the entire governance system to operate efficiently. Additionally, an effective interest allocation mechanism between production organizations and industry associations can incentivize industry associations to continuously play their roles;

- (3)

- The regulatory strategies of local governments in the different development stages of the geographical indication industry exhibit stability differences, mainly influenced by regulatory benefits, regulatory costs, and the degree of collaboration with industry associations. Hence, the selection of local government regulatory strategies is a dynamic adjustment process aimed at maximizing regulatory benefits. Furthermore, subsidies from higher-level governments are crucial factors affecting their strategic choices. In the initial stage of industry development, subsidies from higher-level governments are of vital importance for local governments to play a leading role;

- (4)

- Effective regulatory mechanisms and reputation mechanisms are of vital significance for the quality governance of geographical indication agricultural products. The more efficient the regulation is, the greater the likelihood that the production organization will opt for self-disciplined production. Meanwhile, as a brand profoundly influenced by reputation, the existence of reputation mechanisms can empower consumers to effectively engage in the quality governance of geographical indication agricultural products;

- (5)

- The participation strategies of consumers in the quality governance of geographical indication agricultural products are significantly influenced by their costs of information acquisition, authenticity identification, and complaint. Higher participation and complaint costs may restrain consumers’ active participation. Additionally, the consumer surplus that consumers obtain from the consumption of geographical indication products is also a key factor affecting their participation in governance. The more consumer surplus consumers perceive, the higher their willingness to participate in governance tends to be.

5.2. Management Insights

- (1)

- During the initial stage of the geographical indication industry’s development, the higher-level government ought to offer financial subsidies to local governments that can effectively alleviate their financial strain. Such financial support not only mitigates the financial burden of local governments but also boosts their motivation and capacity to fulfill their supervisory duties, fully mobilizing their initiative in quality governance. For example, in the quality-related incidents involving “Wuchang Rice” and “Yangcheng Lake Crabs”, if the higher-level government provides adequate financial support to the local government responsible for the brand, it can empower the local government to strengthen regulatory efforts, identify counterfeiting issues within the supply chain at an earlier stage, and thereby protect the brand from sustaining significant reputational damage;

- (2)

- Local governments should place significant emphasis on the role of geographical indication industry associations and provide operating subsidies to heighten their willingness to participate in governance. They should also collaborate with the associations to establish quality standards for geographical indication of agricultural products. During the initial stage of industry development, local governments should closely cooperate with industry associations to explore efficient supervisory models to reduce supervisory costs and enhance supervisory efficiency. In the mature stage of the industry, local governments should gradually delegate powers and clarify the responsibilities of industry associations in aspects such as standard formulation, production supervision, infringement handling, etc. Both sides should also actively coordinate the participation of stakeholders like farmers, enterprises, and research institutions to ensure that the standards not only reflect the actual demands of the industry but also enjoy wide recognition. Under the guidance of the local agricultural and rural affairs bureau and the market supervision bureau, Yangcheng Lake Town established a specialized Yangcheng Lake hairy crab industry association. This association not only enforces industry supervision but also actively engages in brand promotion and technical support, thereby playing a highly constructive role in safeguarding the geographical indication status of “Yangcheng Lake Hairy Crab”;

- (3)

- By constructing a multi-party value co-creation system based on blockchain technology, it is feasible to promote coordinated development within the geographical indication agricultural products sector through technological empowerment. The regulatory function of blockchain furnishes transparent tools for local governments and industry associations to dynamically monitor production processes and quality certification, thereby ensuring the credibility of products. Consumers can engage in evaluation via the blockchain platform, forming a reputation-based feedback mechanism that not only prompts producers to enhance product quality but also strengthens consumer trust in products. Simultaneously, smart contracts supported by blockchain can optimize the distribution of interests between production organizations and industry associations, guaranteeing fair rewards and stimulating in-depth participation from multiple parties. Through closely connecting producers, governments, industry associations, and consumers, blockchain technology can break through the trust bottleneck of traditional collaboration and establish a transparent, fair, and mutually beneficial value co-creation ecosystem. Recently, Xingkuang Technology, a subsidiary of the Tianxiangxiu Group, has partnered with the “Gusu Chengwai” hairy crab brand to launch “Digital Traceability Crabs” integrated with anti-counterfeiting codes. By leveraging blockchain technology, this initiative enables digital traceability for Yangcheng Lake hairy crabs, significantly assisting consumers in overcoming information asymmetry. On one hand, it helps reduce the production and distribution costs associated with Yangcheng Lake hairy crabs; on the other hand, it effectively minimizes the risk of counterfeit and substandard products entering the market.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, General Office. Implementation Plan for Supporting the Development of Regional Public Brands in Poverty-Alleviated Areas (2023–2025). 2023. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/govpublic/SCYJJXXS/202304/t20230420_6425711.htm (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Giampieri, F.; Mazzoni, L.; Cianciosi, D.; Alvarez-Suarez, J.M.; Regolo, L.; Sánchez-González, C.; Capocasa, F.; Xiao, J.; Mezzetti, B.; Battino, M. Organic vs conventional plant-based foods: A review. Food Chem. 2022, 383, 132352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Han, T. Exploring the Improvement of Geographical Indication Protection System. Economic Daily, 23 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Moschini, G.; Menapace, L.; Pick, D. Geographical Indications and the Competitive Provision of Quality in Agricultural Markets. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2008, 90, 794–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Luan, J. Value Characteristics, Realization Approach and Public Governance of Geographical Indication of Agricultural Products. Financ. Trade Res. 2021, 32, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Jean Tirole, A. Theory of Collective Reputations (with applications to the persistence of corruption and to firm quality). Rev. Econ. Stud. 1996, 63, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Gao, X. Regional Quality Reputation and Export Quality of Agricultural Products: Concurrently Discussing the Issue of ‘Free Riding’ by Enterprises. Macroeconomics 2020, 12, 84–97. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Xu, J.; Shi, G.; Huang, X. Evaluation and countermeasures for the secure supply of fruit and vegetable products in jiangyin, China. Agro Food Ind. Hi-Tech 2016, 27, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Hug, S.; Irek, J.; Finger, R. Product differentiation, quality, and milk price stability: The case of the Swiss cheese market. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2025, 47, 416–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menapace, L.; Moschini, G.C. Strength of protection for geographical indications: Promotion incentives and welfare effects. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2014, 96, 1030–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones-Ruiz, X.F.; Penker, M.; Belletti, G.; Marescotti, A.; Scaramuzzi, S. Why early collective action pays off: Evidence from setting Protected Geographical Indications. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2017, 32, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boga, R.; Paül, V. ‘Because of its size, it’s not worth it!’: The viability of small-scale geographical indication schemes. Food Policy 2023, 121, 102549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cei, L.; Defrancesco, E.; Stefani, G. From geographical indications to rural development: A review of the economic effects of European Union policy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poetschki, K.; Peerlings, J.; Dries, L. The impact of geographical indications on farm incomes in the EU olives and wine sector. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 579–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Qian, W. The Free-rider Problem in the Construction of Region Public Brands of Agricultural Products: An Analysis Based on Governance Study of Digital Traceability, Transparency and Assurances Systems. China Rural. Surv. 2022, 6, 142–162. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.; Zheng, S. Research on the Use of Regional Public Brand for Agricultural Products by Farmers: Collective Action Dilemma and Self-Organized Governance. J. Rural Econ. 2018, 2, 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Li, G.; Luo, C. The Mechanism and Improvement Strategy of Value Co-creation for Regional Shared Brand in Agricultural Product. J. Hubei Eng. Univ. 2023, 43, 118–122. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y. Research on the Construction of Agricultural Product Geographical Indication Brands in the Perspective of Economic Law in China. J. Southeast Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2020, 22, 90–93. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Yang, H.; Zeng, L.; Li, X. The Evolutionary Game of Three Parties Participating in the Promotion of Regional Brands of Agricultural Products. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2022, 30, 196–209. [Google Scholar]

- Barjolle, D.; Quiñones-Ruiz, X.F.; Bagal, M.; Comoé, H. The role of the state for geographical indications of coffee: Case studies from Colombia and Kenya. World Dev. 2017, 98, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Xie, C.; Ma, L. Tripartite evolutionary game and simulation analysis of brand enhancement for geographical indications agri-food. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2024, 16, 340–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Geng, X. A Study on the Governance of Opportunistic Behavior of Geographical Indications Agricultural Producers:Based on the Perspective of Collective Action. Econ. Manag. 2022, 36, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Belletti, G.; Marescotti, A. Origin products, geographical indications and rural development. In Labels of Origin for Food: Local Development, Global Recognition; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2011; pp. 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Wang, L.; Yu, Y. Research on Applying “Double Engines” of Government and Market to Strengthen the Construction of Regional Public Brands of Agricultural Products. Collect. Essays Financ. Econ. 2022, 38, 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Cayambe, J.; Heredia-R, M.; Torres, E.; Puhl, L.; Torres, B.; Barreto, D.; Heredia, B.N.; Vaca-Lucero, A.; Diaz-Ambrona, C.G. Evaluation of sustainability in strawberry crops production under greenhouse and open-field systems in the Andes. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2023, 21, 2255449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.B.; Elshaikh, N.A.; Hong, L.; Adam, A.B.; Yan, H. Conservation tillage as an approach to enhance crops water use efficiency. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B—Soil Plant Sci. 2017, 67, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, X.; Yan, H.; Ullah, I.; Zuo, Z.; Li, L.; Yu, J. Effects of irrigation quantity and biochar on soil physical properties, growth characteristics, yield and quality of greenhouse tomato. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 241, 106263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darko, R.O.; Yuan, S.; Hong, L.; Liu, J.; Yan, H. Irrigation, a productive tool for food security—A review. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B—Soil Plant Sci. 2016, 66, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Hu, Y.; Ali Buttar, N.; Mahmood, A. X-ray computed tomography for quality inspection of agricultural products: A review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 3146–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Yu, P.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Lu, C.; Jiang, X. Application status and prospect of impedance spectroscopy in agricultural product quality detection. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; He, Y.; Yuan, B.; Li, L.; Luo, L.; You, T. Simultaneous detection of multiple mycotoxins in agricultural products: Recent advances in optical and electrochemical sensing methods. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e70062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Jin, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, L. The Evolutionary Game of Quality Regulation among Government, Enterprise and Consumer in the Social Media Environment. Manag. Rev. 2023, 35, 248–261. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. From repeat patronage to value co-creation in service ecosystems: A transcending conceptualization of relationship. J. Bus. Mark. Manag. 2010, 4, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Sun, J. Research on Collaborative Co-construction of Regional Brand of Agricultural Products Under Rural Revitalization Strategy—From the Perspective of Value Co-creation. Res. Econ. Manag. 2022, 43, 96–110. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, M.A. Asymmetric evolutionary games with non-linear pure strategy payoffs. Games Econ. Behav. 2008, 63, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Kock, N. An evolutionary game theoretic perspective on e-collaboration: The collaboration effort and media relativeness. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 194, 821–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.D.; Jonker, L.B. Evolutionary stable strategies and game dynamics. Math. Biosci. 1978, 40, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzberger, K.; Weibull, J.W. Evolutionary selection in normal-form games. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1995, 63, 1371–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzhou Municipal Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. What Do Producers and Operators Say About Suzhou’s ‘Three Products and One Label’ Agricultural Products? Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzU0NDc4NTMwMw==&mid=2247593066&idx=2&sn=d943d4c40c9c8a28137be46757ccc6a2&chksm=fb75fa92cc027384590d87667e519424f2df4e01120e99dbf5a757ed24340b0a2936c3f12ea6&scene=27 (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Jiang, Y.; Pu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Ji, S.; Yu, H. Premium Between Geographical Indications of Agricultural Products and Corporate Brands and Their Synergistic Effect: Taking Green Tea for Example. Econ. Geogr. 2023, 43, 179–186. [Google Scholar]

- National Intellectual Property Administration, China. Measures for the Protection of Geographical Indications Products. 2024. Available online: https://www.cnipa.gov.cn/art/2024/1/2/art_2790_189522.html (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress of China. Product Quality Law of the People’s Republic of China; Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress of China: Beijing, China, 2023.

- Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress of China. Food Safety Law of the People’s Republic of China; Committee of the National People’s Congress of China: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Huo, H.; Liu, X. Behavioral decision-making of government, agricultural product producers, and consumers on agricultural product quality and safety regulation in a digital environment. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1373747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Ling, Z.; Chen, X. Selection of Behavior Strategy for Quality Investment in Food Supply Chain under Social Co-governance Framework. J. Macro-Qual. Res. 2024, 12, 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, C.; Wang, J.; Perc, M.; Wang, Z. Reputation and reciprocity. J. Phys. Life Rev. 2023, 46, 8–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Yao, J. Government Interference, Consumer Purchase Behavior and Brand Construction of Agricultural Products: Based on Tripartite Evolutionary Game Theory. J. Agro-For. Econ. Manag. 2023, 22, 171–181. [Google Scholar]

- Ganzhou Municipal Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. 2024 Department Budget Disclosure of Ganzhou Municipal Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. Available online: https://www.ganzhou.gov.cn/zfxxgk/c116058/202404/10e34e931a6b4a04a7ab91ea8bc0356e.shtml (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Zhao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chu, N. Evolutionary Game Analysis of Internal Employee’s Participation in Product Quality Supervision. Oper. Res. Manag. Sci. 2023, 32, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ganzhou Gannan Navel Orange Association. Articles of Association of Ganzhou Gannan Navel Orange Association; Ganzhou Gannan Navel Orange Association: Ganzhou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Y.; Shao, J.; Mu, Y. The Role of Agricultural Product Industry Associations in Agricultural Industrialization: A Case Study of Heilongjiang Province. Acad. Exch. 2009, 1, 78–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China. Notice on the Cancellation of Direct Central Government Funding for Industry Associations and Chambers of Commerce from 2018. 27 October 2015. Available online: http://www.mof.gov.cn/index.htm (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Lyu, S. Reflection on Chinese Subsidy and Bonus Policies of Geographical Indications of Agricultural Products in China Based on the Reform Trend of CAP in EU. Int. Econ. Trade Res. 2015, 31, 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Saïdi, M.; Ay, J.S.; Marette, S.; Martin, C. Willingness-to-pay for reshuffling geographical indications. J. Wine Econ. 2020, 15, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| The additional costs arisen for agricultural product production organizations during self-regulatory production | |

| The additional costs incurred when the local government imposes strict regulations | |

| Additional costs incurred by trade associations in fulfilling their responsibilities | |

| The cost of consumer participation in governance | |

| The additional revenue derived from the sale of agricultural products under the name of geographical indication products | |

| The regulatory gains from strict local government regulation | |

| Benefits of active engagement by industry association | |

| Subsidies received from the local government when the association actively fulfills its responsibilities | |

| The association saves the cost of improving quality for self-regulated production organizations | |

| The association saves the government the cost of regulatory oversight. | |

| The association saves information collection costs for consumers who participate in governance | |

| The cost of consumer complaints | |

| Punishment by local government and associations for unregulated enterprises | |

| Liability of production organization to consumer | |

| The brand reputation that it brings to the organization of production | |

| Reputational damage to the production organization | |

| Local governments have been held accountable by higher-level governments and suffered reputational losses | |

| Reputational damage to trade associations | |

| Taxes imposed by the government when agricultural products are sold under the name of geographical indications | |

| Consumer surplus when consumers purchase high-quality agricultural products while participating in governance | |

| The consumer surplus of consumers who consume ordinary products versus consumers who consume landmark products when no regulation is in place | |

| Consumer surplus from purchasing low-quality agricultural products | |

| The probability of successful regulation when local governments exercise strict oversight | |

| The probability of regulatory success when trade associations actively fulfill their responsibilities | |

| The probability of successful co-regulation between local governments and industry associations |

| Participants | Local Government (G) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer (C) | |||||||

| Participating | Not Participating Temporarily | Participating | Not Participating Temporarily | ||||

| Industry association (A) | Actively fulfilling responsibilities ( | Production organization (P) | Standardize production ( | ( | ( | ( | ( |

| Unstandardized production ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | |||

| Negatively fulfilling responsibilities ( | Standardize production ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | ||

| Unstandardized production ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | |||

| Equilibrium Poin | Jacobian Matrix Eigenvalues | Symbol | Stability | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditional ESS | ||||||

| Conditional ESS | ||||||

| Conditional ESS | ||||||

| Unstable point | ||||||

| Conditional ESS | ||||||

| Conditional ESS | ||||||

| Unstable point | ||||||

| Unstable point | ||||||

| Equilibrium Poin | Jacobian Matrix Eigenvalues | Symbol | Stability | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditional ESS | ||||||

| Conditional ESS | ||||||

| Conditional ESS | ||||||

| 0 | Unstable point | |||||

| Conditional ESS | ||||||

| Conditional ESS | ||||||

| Unstable point | ||||||

| Unstable point | ||||||

| Variable | |||||||||||||

| Value | 15 | 21 | 4 | 1.5 | 2 | 3 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 6 |

| Variable | |||||||||||||

| Value | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 2 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, G.; Zhan, K. Research on the Evolutionary Game of Quality Governance of Geographical Indication Agricultural Products in China: From the Perspective of Industry Self-Governance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3414. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083414

Zhao G, Zhan K. Research on the Evolutionary Game of Quality Governance of Geographical Indication Agricultural Products in China: From the Perspective of Industry Self-Governance. Sustainability. 2025; 17(8):3414. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083414

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Guanbing, and Kuijian Zhan. 2025. "Research on the Evolutionary Game of Quality Governance of Geographical Indication Agricultural Products in China: From the Perspective of Industry Self-Governance" Sustainability 17, no. 8: 3414. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083414

APA StyleZhao, G., & Zhan, K. (2025). Research on the Evolutionary Game of Quality Governance of Geographical Indication Agricultural Products in China: From the Perspective of Industry Self-Governance. Sustainability, 17(8), 3414. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083414