1. Introduction

With the continuous growth of the global economy, environmental issues have become a major challenge that urgently needs to be addressed. Problems such as climate change, resource depletion, water scarcity, and pollution are becoming increasingly severe and have had profound impacts on the global ecosystem and socio-economic systems. The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) explicitly highlight that environmental protection and sustainable resource utilization are among the core issues of global development [

1,

2,

3]. To address these challenges, governments, businesses, and international organizations worldwide have implemented a series of policy measures aimed at promoting a green economy and environmental protection. However, balancing economic growth with ecological sustainability has become a common goal for all stakeholders [

4,

5,

6]. In particular, for traditional high-pollution industries, transitioning to a green economic model is not only a significant task for policymakers but also a critical challenge faced by businesses [

6,

7,

8]. Therefore, promoting green innovation has become an important approach to addressing the environmental crisis, enabling a win–win situation for both the economy and the environment.

Corporate green innovation is driven by various factors. Specifically, technological advancements play a key role in innovations related to green energy (such as solar and wind energy) and environmental protection processes. Bi’s research shows that adopting low-carbon technologies and efficient production processes not only reduces pollution but also enhances the competitiveness of enterprises [

9]. Secondly, market demand, particularly consumer preferences for environmentally friendly products, has driven businesses to innovate in green products and services. Song’s research indicates that with the growing environmental awareness, consumer demand for electric vehicles and green home appliances has led businesses to increase their investment in research and development (R&D) [

10]. On the internal governance side, Abbas mentions that leadership decisions and an innovation-driven culture are crucial for green technology R&D [

11], while Cao et al. further emphasize the impact of long-term R&D investments on green innovation. External competitive pressure also plays an important role [

12]. Bataineh et al. found that green innovation by peer companies motivates competitors to follow suit, driving the overall green transformation of the industry. Additionally, supply chain management, by promoting green procurement and industry chain collaboration, further drives the expansion of green innovation [

13]. Zhao et al. highlights that through collaboration with supply chain partners to jointly develop green technologies, companies not only reduce costs but also enhance the overall sustainability of the industry [

14].

Green credit policies, as a mechanism to encourage sustainable business practices, have been gaining attention in recent years. These policies typically involve providing favorable financial conditions, such as lower interest rates or financial subsidies, to firms that meet specific environmental standards. The idea is to incentivize companies to engage in environmentally friendly practices, including green technology research and development (R&D), pollution control investments, and the adoption of green production processes [

15].

Several studies have explored the impact of green credit policies on corporate behavior. For instance, Wang et al. (2018) examined how green credit policies in China have provided firms with financial incentives to invest in cleaner technologies, leading to a reduction in pollution and a boost in green innovation [

16]. Similarly, Zhang et al. (2019) found that access to green credit significantly lowers the financial barriers for firms to adopt green technologies, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that may struggle to obtain traditional financing [

17]. These findings are supported by the work of Tran, who found that the implementation of green credit policies positively impacts firms’ willingness to invest in green R&D and increases their environmental performance, especially in pollution-intensive industries [

18].

In addition, some studies have highlighted the role of green credit policies in promoting the green transformation of industries. For example, Negi et al. suggested that green credit policies not only encourage individual firms to adopt cleaner technologies but also foster industry-wide shifts toward more sustainable practices [

19]. They argue that firms in industries with more stringent environmental regulations tend to benefit more from green credit policies, as these policies reduce the cost of compliance with environmental standards and promote innovation in sustainable technologies.

However, the effectiveness of green credit policies is not without debate. Some researchers have questioned whether the policies are sufficiently robust to drive significant change, particularly in sectors that are heavily reliant on traditional, high-pollution industries. For instance, Zhang argued that while green credit policies provide short-term financial relief, they may not lead to sustained long-term investment in green technologies unless complemented by other regulatory or market-driven incentives [

20].

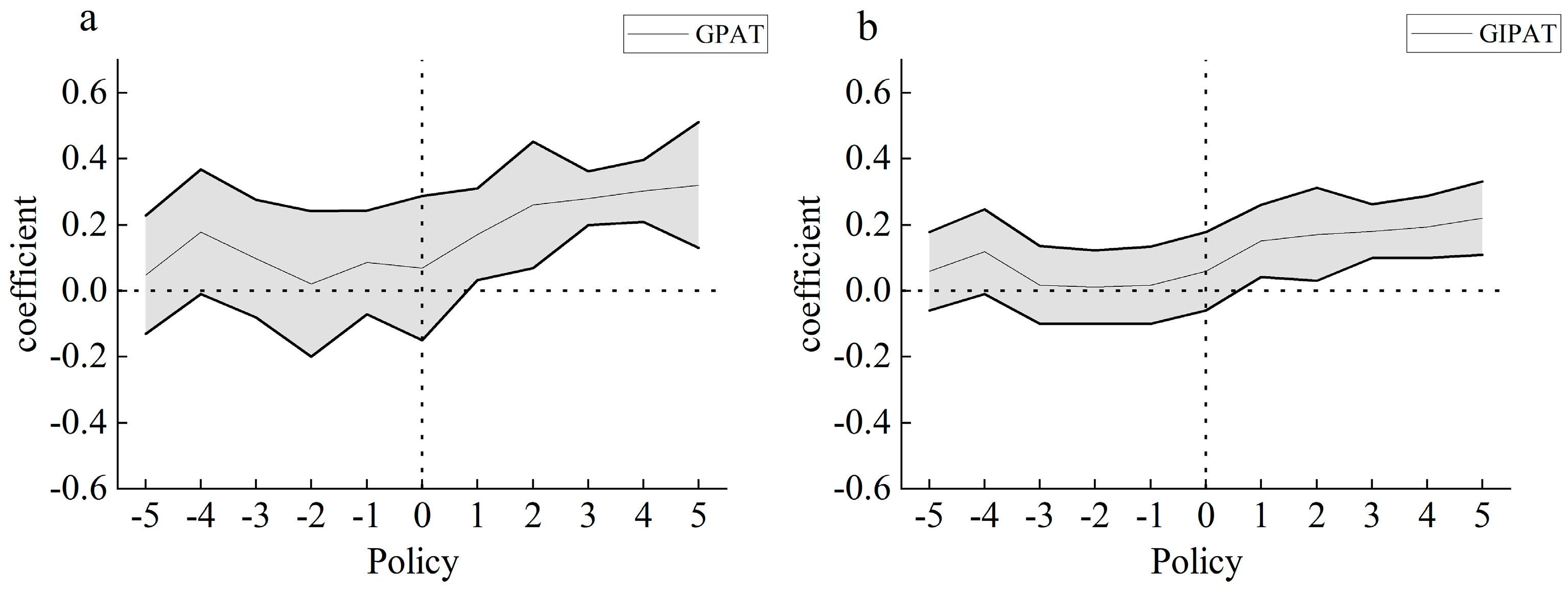

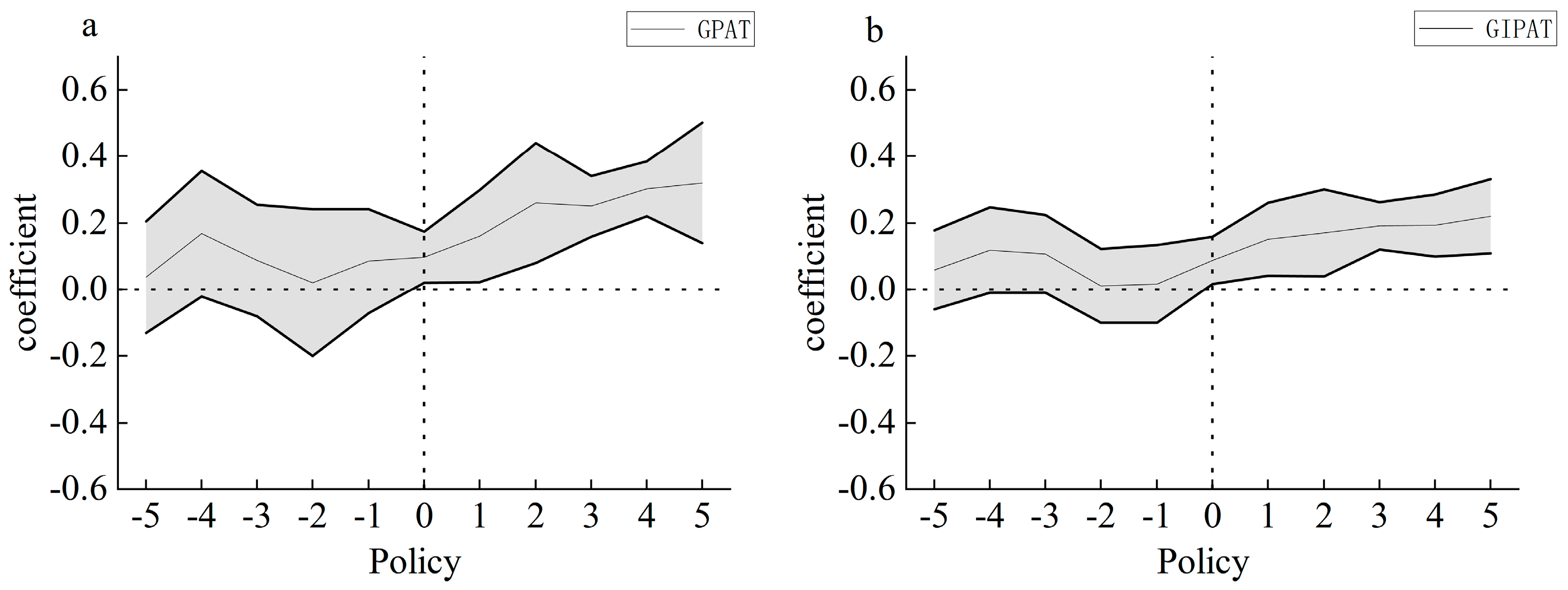

This study uses enterprise-level data from China to empirically analyze the impact of green credit policies on corporate green innovation through a difference-in-differences (DID) approach, particularly exploring the differentiated effects of green credit policies across different types of enterprises. At the same time, one of the significant innovations of this study is that, in addition to focusing on the direct impact of green credit policies, it also examines the moderating role of analyst attention in the relationship between green credit policies and corporate green innovation. As a key intermediary in the capital markets, analysts can influence investors’ evaluation of a company’s environmental performance by focusing on its green innovation activities, which in turn affects the company’s financing ability and market reputation. Therefore, this study not only analyzes the driving factors of green innovation from a policy perspective but also introduces the external capital market factor—analyst attention—providing a new perspective for understanding the mechanisms that drive green innovation.

3. Research Design

3.1. Research Sample and Data Sources

This study selects A-share listed companies from 2007 to 2023 as the research sample. The sample is processed according to the following criteria: abnormally traded listed companies classified as ST (special treatment), *ST (special treatment with risk warning), and PT (particularly traded) are excluded. These classifications are used to identify companies that are facing significant financial difficulties or have been placed under special supervision by regulatory authorities, which may affect their reliability for research purposes. Additionally, samples with missing relevant indicators, such as missing financial performance data (e.g., total assets, revenue, or net income) or incomplete corporate governance information (e.g., board composition or ownership structure), were removed from the sample. After data processing, a total of 51,170 annual observations were obtained. All data were sourced from the Wind and CSMAR databases, which are widely recognized and extensively used in academic and industry research. The Wind and CSMAR databases were selected for several reasons. First, both databases provide comprehensive and accurate financial, market, and corporate governance data for A-share listed companies, making them reliable sources for analyzing Chinese listed firms. Second, these databases are frequently used in academic studies in China, ensuring that the results are comparable to those of the existing literature. Wind offers a wide range of financial and economic indicators, while CSMAR provides detailed data on corporate governance and firm-level information, which are essential for this study.

3.2. Variable Selection and Measurement

Dependent Variable. This study measures corporate green innovation using the number of green patent applications. The logarithm of the number of green patent applications plus one is taken as the metric for corporate green innovation activities (GPATs), expressed as ln(GreenPatent + 1), where GreenPatent represents the number of green patent applications. Furthermore, the number of green invention patents (GIPATs) is used as an indicator of the quality of corporate green innovation, allowing a comparison between the quantity and quality of green innovation [

31,

32].

Independent Variable. This study follows the approach of Li et al. by classifying industries based on the environmental and social risk levels outlined in the Key Evaluation Indicators for Green Credit Implementation issued by the former China Securities Regulatory Commission [

33,

34,

35]. According to the “Key Evaluation Indicators for the Implementation of Green Credit” document issued by the Chinese government in 2012, industries belonging to companies classified as Category A for environmental and social risks are identified as restricted industries for green credit. Specifically, industries under Category A include nuclear power generation, hydropower generation, water conservancy and inland river port engineering construction, coal mining and washing, oil and natural gas extraction, black metal mining and selection, non-ferrous metal mining and selection, non-metallic mineral mining and selection, and other mining industries, totaling nine sectors. When a company belongs to one of these nine industries, it is classified as the treatment group; conversely, when it does not belong to these nine industries, it is classified as the control group. The dummy variable post represents the period before and after the policy implementation, taking the value of 0 before the policy and 1 after the policy.

Moderating Variable. Analyst attention is measured by taking the natural logarithm of the number of securities analysts covering the same listed company plus one [

36,

37].

Control Variables. The control variables include the debt-to-asset ratio, return on assets (ROAs), return on equity (ROE), total operating cost ratio, operating profit margin, Tobin’s Q, book-to-market ratio, total assets (log-transformed), fixed asset ratio, board size (log-transformed), revenue growth rate, cash holdings ratio, and ownership concentration [

38,

39,

40]. The variable definitions are shown in

Table 1.

3.3. Model Construction

The difference-in-differences (DID) method is a widely used empirical research technique in econometrics; it is particularly suited for evaluating the impact of policy changes on specific groups. This method estimates the policy effect by comparing the changes before and after the policy implementation between the treatment group (affected by the policy) and the control group (unaffected by the policy). The basic idea is to compare the changes in the treatment and control groups before and after the policy intervention, thereby controlling for unobservable fixed factors that may influence the variable being studied.

In this study, the DID method is used to assess the impact of the green credit policy on corporate green innovation. By dividing firms into high-pollution enterprises (treatment group) and non-high-pollution enterprises (control group) and observing the changes before and after the policy implementation, the specific impact of the green credit policy can be effectively identified.

To investigate the impact of the green credit policy on corporate green innovation and test hypothesis H1, this study constructs a two-way fixed effects model (1).

where Y is the dependent variable representing the number of green innovations by the enterprise, with subscripts i and t denoting the enterprise and the year, respectively. The independent variable (DID) represents the difference-in-differences term. This study classifies industries based on environmental and social risk levels, dividing firms into high-pollution and non-high-pollution enterprises. If the enterprise is a high-pollution enterprise, it is considered the treatment group, with the treatment taking the value of 1; non-high-pollution enterprises are the control group, with the treatment taking the value of 0. The variable post takes the value of 0 before the policy implementation and 1 afterward. The interaction term (

)t measures the effect of the green credit policy on corporate green innovation. β represents the coefficients of the variables, and control denotes the control variables. To ensure the robustness of the empirical results, the model includes both firm fixed effects (

) and year fixed effects (

), with the random disturbance term represented as

.

Furthermore, to examine the moderating role of analyst attention in the impact of the green credit policy on corporate green innovation, and to test hypothesis H2, this study constructs a two-way fixed effects model (2).

where Y represents the dependent variable, which is the number of green innovations by the enterprise; DID represents the independent variable, the difference-in-differences term; afnum denotes the moderating variable, analyst attention;

represents the interaction term between analyst attention and DID; control represents the control variables; and β denotes the coefficients of each variable.

represents the firm fixed effects,

represents the year fixed effects, and

is the random disturbance term.

6. Moderating Effect

Considering that the effect of the “Green Credit Guidelines” on corporate green innovation may vary due to differences in analyst attention, this study adds an interaction term between analyst attention and DID in the benchmark regression model to further verify hypothesis H2.

As shown in

Table 6, columns (1) and (3) present the regression results of model (4-1) with fixed effects, while columns (2) and (4) reveal the results of model (4-2). These results not only provide empirical evidence in support of the hypothesis but also further confirm the assumptions made earlier. Specifically, the results show that the dummy variable (DID) is significantly positively correlated with the quantity (GPAT) and quality (GIPAT) of corporate green innovation activities. This means that when enterprises are influenced by the green credit policy, their green innovation behaviors are promoted in terms of both quantity and quality. Additionally, the interaction term of analyst attention plays an important role. It is closely related to the quantity and quality of corporate green innovation and is statistically significant at the 1% level. This finding indicates that the level of analyst attention to a company’s information can positively moderate the impact of the green credit policy on corporate green innovation. In other words, when more analysts begin to focus on a company’s green innovation activities, this attention may encourage the company to be more proactive in green innovation, thereby improving the overall effectiveness of its innovation activities.

In summary, these regression results strongly validate hypothesis H2a, indicating that, in the context of the green credit policy, analyst attention can serve as an important moderating variable that affects the quantity and quality of corporate green innovation activities. This helps further understand and assess how analysts influence a company’s green innovation strategy through their attention to information, and how this strategy is impacted by the external policy environment. For policymakers, this is undoubtedly an important signal, suggesting that when designing relevant incentive measures, they should consider how to better mobilize analysts’ enthusiasm to achieve the best green innovation outcomes.

7. Heterogeneity Analysis

7.1. State-Owned Enterprise or Not

To further explore the heterogeneous effects of the green credit policy, this study analyzes the differences in green innovation between state-owned and non-state-owned enterprises. The results are shown in

Table 7. According to relevant theories and empirical studies, state-owned enterprises tend to respond better to government policy incentives, particularly benefiting from clear advantages in policy support and financing channels. Therefore, we hypothesize that the green credit policy has a more significant impact on green innovation in state-owned enterprises, while the response from non-state-owned enterprises is relatively weaker [

45].

The regression results show that the green credit policy has a significant positive impact on green innovation in state-owned enterprises. Specifically, state-owned enterprises experienced a significant increase in the number of green patent applications (GPATs) and green invention patent applications (GIPATs) after the policy was implemented, indicating that the green credit policy plays a strong role in promoting green innovation in state-owned enterprises. With the support of government policies and guidance, state-owned enterprises are better positioned to leverage the incentives of the green credit policy to drive technological innovation and industrial upgrading.

However, the performance of non-state-owned enterprises after the implementation of the green credit policy is relatively weaker. The regression analysis shows that there was no significant increase in the number of green patents and invention patents filed by non-state-owned enterprises, suggesting that the green credit policy has a limited impact on their green innovation activities. Non-state-owned enterprises may face higher financing costs and have relatively fewer resources and policy support, which could be the reason for their weaker response to green innovation.

7.2. Firm Size

To further analyze the heterogeneous impact of the green credit policy on corporate green innovation, this study also examines the issue from the perspective of firm size. According to resource dependency theory and research on policy implementation effects, larger firms typically have more resources, stronger financing abilities, and greater capacity to adapt to policies. Therefore, we hypothesize that the green credit policy has a more significant impact on the green innovation of large firms [

46,

47].

First, we classify the sample firms into large and small enterprises based on their size. Large firms are defined according to total asset size. Generally, large firms have stronger competitiveness in capital, technology, market access, and talent, and they are more likely to benefit from government policies. Small firms, on the other hand, may struggle to fully utilize policy support due to limited resources, leading to a weaker response in green innovation activities.

The regression analysis results show that the green credit policy has a significant positive impact on the green innovation of large firms (

Table 8). Specifically, the number of green patent applications (GPATs) and the number of green invention patent applications (GIPATs) significantly increased in large firms after the policy was implemented, indicating that large firms are able to effectively leverage the incentives in the green credit policy to drive the research and application of green technologies. This could be due to the fact that large firms have more financial and technological reserves, allowing them to increase investments in green R&D and achieve green transformation under the policy’s impetus.

However, while small firms are also affected by the green credit policy, the increase in their green innovation is relatively small, and the changes in their green patent applications are not as significant as those in large firms. This may be because small firms face resource constraints in areas such as capital and technology, making it difficult for them to respond to and absorb the policy benefits as quickly as large firms, resulting in weaker momentum for green innovation.

7.3. Excess Cash or Not

To further explore the heterogeneous effects of the green credit policy, this study analyzes the issue from the perspective of whether firms hold excess cash. A firm’s cash flow situation significantly influences its innovation capacity and policy response. Specifically, firms that hold excess cash typically have more financial flexibility, making it easier for them to invest in green innovation [

48]. Therefore, we hypothesize that firms holding excess cash will respond more significantly to the green credit policy in terms of green innovation. The results are shown in

Table 9.

In this study, surplus cash is defined as the difference between the cash held by a firm and its normal cash requirements. Firms that hold cash amounts greater than the industry average are classified as having surplus cash. We group the sample firms based on whether they possess surplus cash and examine the changes in their green innovation before and after the implementation of the green credit policy.

The regression results show that firms with excess cash experienced a significant increase in both the number of green patent applications (GPATs) and the number of green invention patent applications (GIPATs) after the policy was implemented. This suggests that firms with excess cash have more financial support, allowing them to invest more actively in green technology R&D and to fully leverage the incentives provided by the green credit policy, thereby driving the growth of green innovation.

In contrast, firms without excess cash showed a smaller increase in green innovation after the policy implementation, with no significant changes in their green patent applications. This could be because these firms face tighter financial conditions and are unable to fully utilize the policy resources for technological innovation, resulting in a weaker response to green innovation.

8. Conclusions and Recommendation

8.1. Conclusions

This study investigates the impact of green credit policies on corporate green innovation, focusing on A-share listed companies in China from 2007 to 2023. Using a difference-in-differences (DID) model, the results reveal significant findings regarding the effectiveness of green credit policies in promoting green innovation, particularly in high-pollution enterprises. The study also examines moderating factors, such as state ownership, firm size, and excess cash holdings, which influence the responsiveness of firms to the policy.

The findings confirm that the green credit policy has a significant positive impact on both the quantity and quality of green innovation. High-pollution enterprises, in particular, showed notable improvements in green innovation after the policy was implemented. This suggests that the policy provides effective incentives for high-pollution industries to adopt greener technologies, resulting in both an increase in the number of green patents and an improvement in the quality of those patents. These findings underscore the policy’s role in facilitating the transformation and upgrading of high-pollution enterprises towards greener practices.

Additionally, the study reveals that state-owned enterprises respond more significantly to the green credit policy than non-state-owned enterprises; this is likely due to their better access to financial resources and government support. Large enterprises, with their larger financial and technological reserves, also exhibit more significant improvements in green innovation following the policy implementation. In contrast, small enterprises, particularly those without excess cash, show weaker responses to the policy. This suggests that financial constraints limit the ability of smaller firms to fully capitalize on the incentives offered by the green credit policy, resulting in less substantial improvements in green innovation.

The study also highlights the important moderating role of analyst attention. It finds that when firms attract more attention from analysts, their green innovation activities improve significantly. This suggests that external attention can amplify the effects of the green credit policy, motivating firms to enhance their green innovation efforts.

8.2. Recommendations

The results of this study indicate that green credit policies have a significant positive effect on high-pollution industries and large enterprises, particularly state-owned enterprises. Therefore, policymakers should further optimize green credit policies to enhance their targeting. For high-pollution industries, the guidance of green credit should be strengthened by establishing clear environmental standards and corporate performance evaluation systems to ensure that loan funds are directed toward enterprises genuinely committed to green transformation. Additionally, the government can collaborate with financial institutions to establish dedicated green credit funds, providing long-term, low-interest green loans to eligible enterprises, thereby reducing their financing costs and enhancing their motivation for green innovation.

For small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and non-state-owned enterprises, which often face greater financial pressure and financing constraints, the government should provide more tailored support. For example, a green financing guarantee fund could be established to offer loan guarantees for SMEs lacking sufficient collateral, thereby lowering their financing barriers. At the same time, tax incentive policies could be introduced, such as allowing additional deductions for R&D expenses or granting direct tax reductions for companies meeting green innovation standards, encouraging them to increase investment in green technologies. Furthermore, the government could guide large enterprises to collaborate with SMEs in green innovation, facilitating technology sharing and joint innovation to help smaller firms overcome technological and financial constraints.

This study also finds that analyst attention plays a crucial role in promoting corporate green innovation. Therefore, policymakers can take measures to increase capital market attention to green innovation. For instance, a green enterprise rating system could be established, incorporating green innovation performance into public company disclosure requirements and publishing corporate green innovation reports regularly. These initiatives would raise awareness among investors and analysts about green innovation. Additionally, the government could encourage financial institutions and securities analysts to conduct specialized research on green innovation firms, channeling market resources toward green enterprises and further enhancing the effectiveness of green credit policies.

Moreover, it is recommended to expand the coverage of green credit policies beyond traditional high-pollution industries to other sectors with significant environmental impacts. For example, the manufacturing, transportation, and construction industries are also major contributors to carbon emissions and resource consumption. Extending green credit policies to these sectors would further promote the green transition of the entire economic system. The government can tailor industry-specific green credit standards and incentive mechanisms to ensure that the policy effectively drives green innovation across various sectors.

8.3. Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights into the impact of green credit policies on corporate green innovation, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the study focuses on A-share listed companies in China, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other countries or industries. The business environment, regulatory frameworks, and access to green financing may differ significantly across regions, affecting the applicability of the results to non-Chinese contexts.

Second, this study primarily relies on firm-level data from publicly listed companies, which may not fully capture the behavior of smaller firms or those not listed on the stock market. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which may face different challenges and incentives in accessing green credit, are underrepresented in the sample. Future studies could include a broader range of firms, including SMEs and privately held companies, to examine how green credit policies affect different types of firms.

Then, while the study examines the moderating role of analyst attention, other external factors, such as market competition, consumer behavior, and industry-specific regulations, may also influence the effectiveness of green credit policies. Future research could explore these factors in greater depth and analyze their interaction with green credit policies to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the drivers of green innovation.

In addition, in analyzing the impact of the green credit policy, this study classified enterprises in the nine heavily polluting industries into treatment and control groups based on industry classification, referring to the policy documents. However, due to limitations in the data, this study did not further determine whether specific enterprises within these industries actually received green credit support. As a result, there may be instances where some control group enterprises also engage in green credit behaviors or have not received green credit but are attempting to obtain it. Due to the lack of detailed information regarding whether specific enterprises received green credit, this study did not account for this variable difference. Future research is recommended to improve this analysis by using more detailed data.