Opportunities and Constraints in the Horticultural Sector of Botswana: A SWOT Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

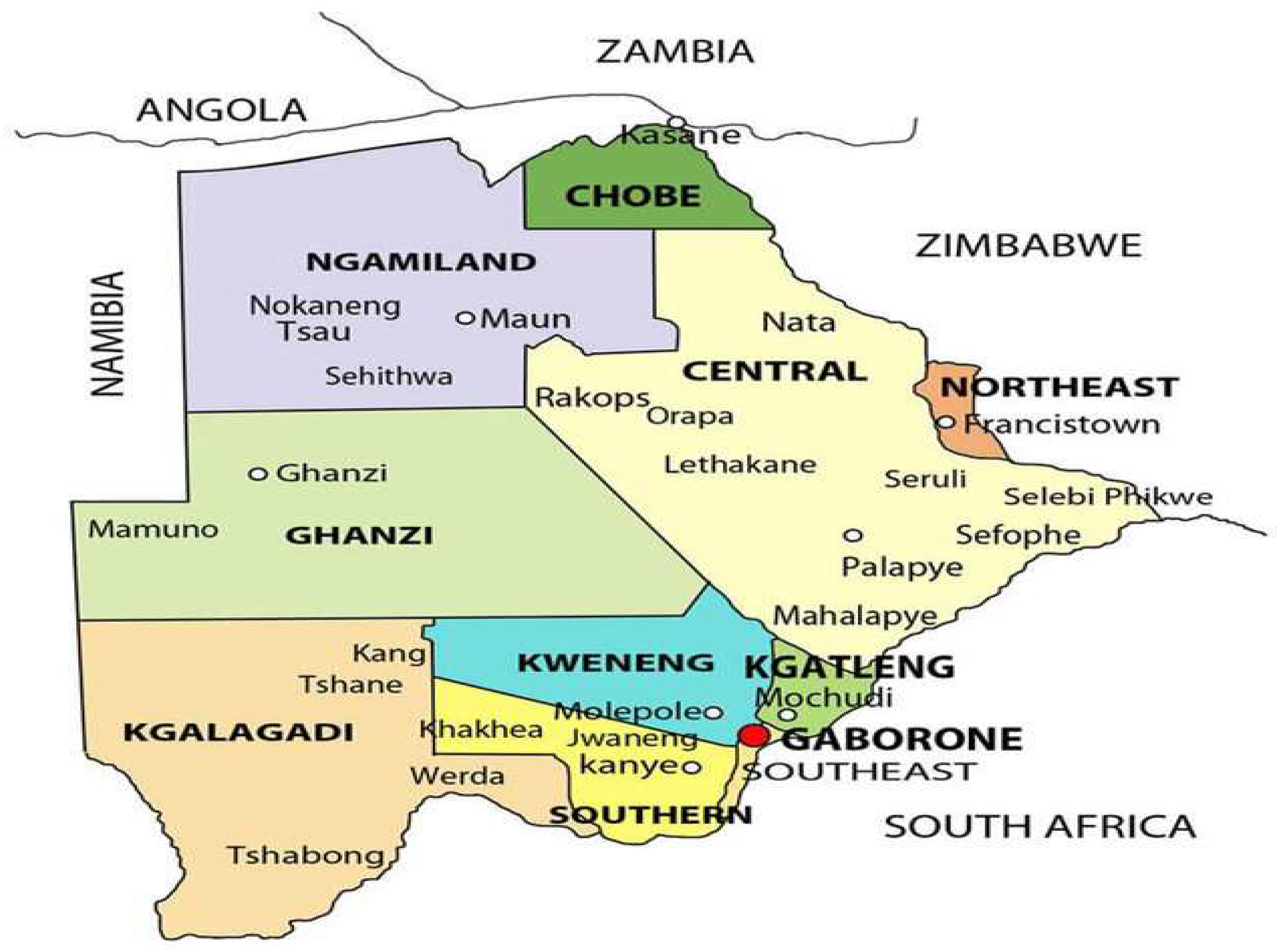

2.1. The Study Area

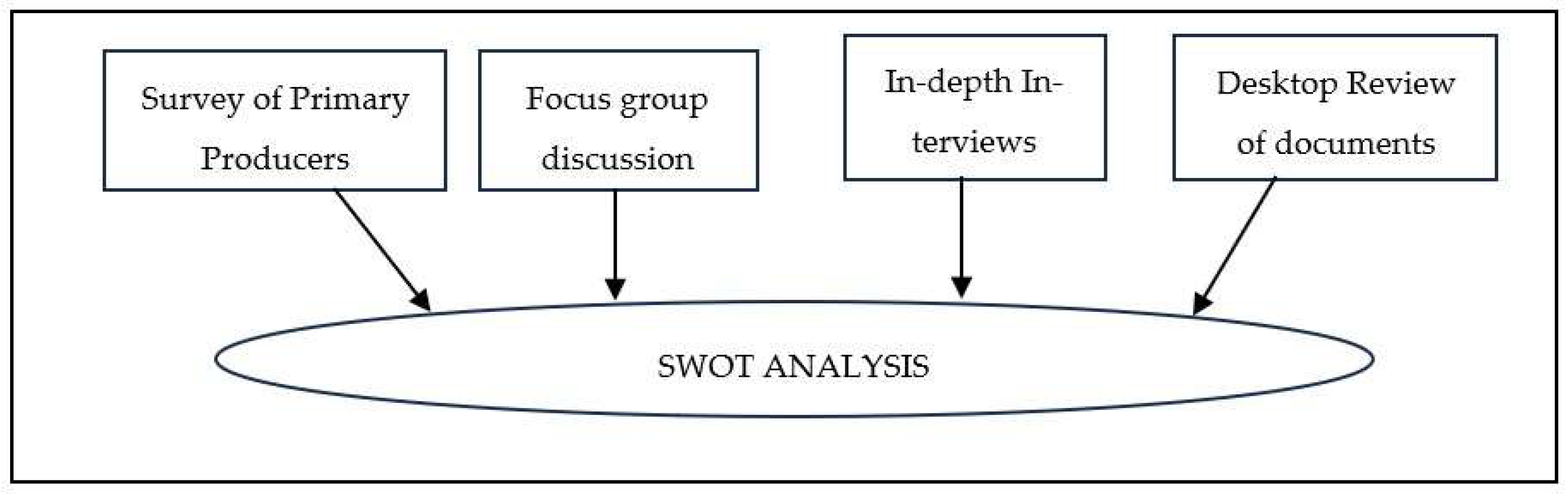

2.2. Data and Data Collection Methods

2.2.1. Survey

2.2.2. In-Depth Interviews

2.2.3. Focus Group Discussions

2.2.4. Desktop Reviews

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Analysis of Survey Data

2.3.2. Analysis of the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats

2.3.3. Characterisation of Producers

3. Results

3.1. SWOT Analysis

3.1.1. Strengths

Supportive Government Programmes

Availability of Land

Availability of Cheap Labour

3.1.2. Weaknesses

Food Safety Issues

Lack of Mandatory Standards

Inadequate Laws Covering Biosecurity

Poor Extension Services

Poor Technical and Farm Business Skills

Lack of Market Access and Corrupt Marketing System

Limited Market Intelligence

Uncoordinated Production

Unskilled Labour

Uncoordinated Support Services

Poor Infrastructure

Limited Access to Credit

3.1.3. Opportunities

Increased Interest in Horticulture

Public Procurement

Sufficient Demand for Vegetables

Processing Potential

Reliable Input Suppliers

3.1.4. Threats

Support Programmes Focused on Primary Production Only

Limited Water Resources

Lack of Interest in the Sector Among the Youth

Removal of the Import Ban

Stiff Competition from Imports

Smuggling of Banned Products

Low Technology Adoption in the Face of Climate Change

Vertical Integration into Primary Production by Retailers

Poor Control of Disease and Pest Outbreaks

Criminal Activities

3.2. Challenges at Each Stage of the Value Chain

3.2.1. Input Supply Challenges at Input Supply

3.2.2. Primary Production Challenges at Primary Production

3.2.3. Challenges at Processing Level

3.2.4. Challenges at End Markets

3.3. Opportunities Along the Value Chain

3.3.1. Input Supply

3.3.2. Primary Production

3.3.3. Processing

3.3.4. End Markets

4. Discussion

4.1. Constraints

4.1.1. Lack of Market Access

4.1.2. Pests and Diseases

4.1.3. Limited Access to Credit

4.1.4. Inadequate Infrastructure

4.2. Opportunities for Improving Value Chain Performance

4.2.1. Import of Most Inputs

4.2.2. Unmet Local Demand and Low Productivity

4.2.3. Lack of Processing

4.2.4. Public Procurement

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Government of Botswana. Second Transitional National Development Plan, April 2023–March 2025. Towards a High-Income Economy: Transformation, Now, Prosperity Tomorrow; National Planning Commission, Office of the President, Government Printer: Gaborone, Botswana, 2023.

- Amao, I. Health benefits of fruits and vegetables: Review from Sub-Sahara Africa. In Vegetables-Importance of Quality Vegetables to Human Health; Asaduzzaman, M.D., Assao, T., Eds.; InTech: London, UK, 2018; pp. 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. International Year of Fruits and Vegetables 2021, Fruits and Vegetables—Your Dietary Requirements, Background Paper; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; 63p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshin, A.; Sur, P.J.; Fay, K.A.; Cornaby, L.; Ferrara, G.; Salama, J.S.; Mullany, E.C. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 195872. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/article/S01406736(19)30041-8/fulltext (accessed on 7 November 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Botswana. Guidelines for Integrated Support Programme for Arable Agriculture Development Programme (ISPAAD); Revised Version; Government Printer: Gaborone, Botswana, 2013.

- Government of Botswana. Guidelines for ISPAAD Horticulture Impact Accelerator Subsidy (IAS); Ministry of Agriculture Development and Food Security, Government Printer: Gaborone, Botswana, 2020.

- Government of Botswana. Control of Goods and Other Charges Act: Chapter 43:08; Government Printer: Gaborone, Botswana, 1973.

- Government of Botswana. Economic Inclusion Act. Act No. 26 of 2021: Chapter 28:05; Government Printer: Gaborone, Botswana, 2021.

- Government of Botswana. National Horticulture Strategy (2022–2030); Revised Final; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture. Horticulture Production Trends; Department of Crop Production, Horticulture Unit: Gaborone, Botswana, 2021.

- Statistics Botswana. International Merchandise Trade Statistics; Statistics Botswana: Gaborone, Botswana, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dubios, T.; Nordey, T.; Opara, L. Unleashing the power of vegetables and fruits in Southern Africa. In Transforming Agriculture in Southern Africa: Constraints, Technologies and Process; Sikora, R.A., Terry, E.R., Vlek, P.L.G., Chitja, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Obi, A.; Maphahama, L. Obstacles to the profitable production and marketing of horticultural products: An offset-constrained modelling of famers’ perceptions. In Institutional Constraints to Smallholder Development in South Africa; Obi, A., Ed.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 169–183. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, M. Constraints and Opportunities for Horticultural Smallholders in Nacala Corridor in Northern Mozambique; Essay on Development Policy; NABEL MAS Cyle, 2012–2014; ETH Zurich: Zurich, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. Improving Market Access for Smallholder Farmers: What Works in Out-Grower Schemes-Evidence from Timor-Leste. 2017, Issue Brief No.1. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/thelab (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Magala, N.M.; Bamanyisa, J.M. Assessment of market options for smallholder horticultural growers and traders in Tanzania. Eur. J. Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 6, 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, B.; Bhattacharjee, M.; Wani, S. Value-chain analysis of horticultural crops-regional analysis in Indian horticultural scenario. IJAR 2020, 6, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapanga, A. A value chain governance framework for economic growth in developing countries. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 20, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Namibian Agronomic Board. Agronomy and Horticulture Market Division, Research and Policy Subdivision. An Analysis of Market Access by Small-Scale Horticulture Producers in Namibia. 2021. Available online: https://www.nab.com.na (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Mathinya, V.N.; Frankie, A.C.; Va De Ven, G.W.J.; Giller, K.E. Productivity and constraints of small-scale crop farming in the summer rainfall region of South Africa. Outlook Agric. 2022, 51, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, S.; Visser, M. South African Horticulture: Opportunities and Challenges for economic and social upgrading in value chains. SSRN 2013, 12, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baliyan, S.P. Improving sustainable vegetable production and income through net shading: A case study of Botswana. J. Agric. Sustain. 2014, 5, 70–103. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, S.K. Horticultural crops and climate change: A review. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 2012, 87, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakre, A.K.; Bisen, A. Challenges of climate change on horticultural crops and mitigation strategies through adoption of extension based smart horticultural practices. Pharma J. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Tejashree, S.G.; Shivalingaiah, Y.N.; Raghuprasad, K.P.S.; Rujar, S.S. Constraints and suggestions given by horticulture crop growers in adoption of precision farming technologies. Int. J. Adv. Biochem. Res. 2024, 8, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, M.A.; Xu, Y.; Iv, Z.; Xu, J.; Shah, I.H.; Sabir, A.; Wang, Y.; Sun, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; et al. Horticulture crop under pressure: Unravelling the impact of climate change on nutrition and fruit cracking. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 357, 120759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondim, D. Value Chain analysis of vegetables (onions, tomato, potato) in Ethiopia: A review. Int. J. Agric. Sci. Food Technol. 2021, 7, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madisa, M.E.; Asefa, Y.; Obopile, M. Assessment of production constraints, crop and pest management in peri-urban vegetable farms in Botswana. Egypt. Acad. J. Biol. Sci. 2010, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, K.S.; Temu, A.E. Access to credit and its effect on the adoption of agricultural technologies: The case of Zanzibar. Sav. Dev. 2008, 32, 45–89. [Google Scholar]

- Dimo, J.C.; Maina, S.W.; Ndiema, A. Access to credit and its relationship with information and communication technology tools’ adoption in agricultural extension among peasants in Rangwe sub-county, Kenya. Asian J. Agric. Ext. Econ. Sociol. 2022, 40, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masca, U.; Mirriam, K.N.; Bor, E.K. Does access to credit influence adoption of good agricultural practices? The case of smallholder potato farmers in Molo sub-county, Kenya. J. Agric. Ext. Rural. Dev. 2022, 14, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdes, R.; Gomez-Castilo, D.; Barrantes, L. Enhancing agricultural value chains through technology adoption: A case study in the horticultural sector of a developing country. Agric. Food Secur. 2023, 12, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, E.; Tsilo, T.J.; Sosibo, N.Z.; Fanadzo, M. Irrigation Wheat Production Constraints and opportunities in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2020, 116, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asian Development Bank (ADB). Sustainable Development and Climate Change Department. Dysfunctional Horticulture Value Chains and the Need for Modern Marketing Infrastructure: The Case of Bangladesh. 2020. Available online: https://www.adb.org/terms-use#openaccess (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- Kibinge, D.; Singh, A.S.; Rugube, L. Small-scale irrigation and production efficiency among vegetable farmers in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa: The DEA Approach. J. Agric. Stud. 2019, 7, 149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Sikora, A.R.; Tery, E.R.; Vlek, P.L.G.; Chitja, J. Overview of Southern African Agriculture. In Transforming Agriculture in Southern Africa: Constraints, Technologies and Process; Sikora, R.A., Terry, E.R., Vlek, P.L.G., Chitja, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- LEA. Horticulture Study on Fresh Fruit and Vegetables in Botswana; Local Enterprise Authority: Gaborone, Botswana, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Madisa, M.E.; Assefa, Y.; Obopile, M. Crop diversity, extension services and marketing outlets of vegetables in Botswana. Egypt. Acad. J. Biol. Sci. 2010, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Baliyan, S.P. Constraints in the growth of horticulture sector in Botswana. J. Soc. Econ. Policy 2012, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- ITC. Horticulture Sector Value Chain Analysis and Action Plan, 2015, Private Sector Development Programme (PSDP), Ministry of Agriculture and Centre for Enterprise Development; ITC: Gaborone, Botswana, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Botswana. Food Control Act: Chapter 65:05; Government Printer: Gaborone, Botswana, 1993.

- Government of Botswana. Plant Protection Act: Chapter 35:02; Government Printer: Gaborone, Botswana, 2009.

- Ministry of Agriculture. Horticulture Production Report, Horticulture Unit 2022/23, 2023; Ministry of Agriculture: Gaborone, Botswana, 2023.

- Statistics Botswana. International Merchandise Statistics; Statistics Botswana: Gaborone, Botswana, 2023.

- Seleka, T.B.; Malope, P.; Madisa, M.E. Baseline Study on Tomato Production, Marketing and Post-Harvest Activities in Botswana; Consultancy Report; Initiative for Development and Equity in African Agriculture (IDEAA): Gaborone, Botswana, 2002. [Google Scholar]

| Method of Data Collection | Type of Respondents | Number of Respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Survey | Primary producers | 102 |

| In-depth interviews | Input suppliers | 9 |

| Wholesalers | 5 | |

| Processors | 1 | |

| Street vendors | 18 | |

| Retailers | 12 | |

| Finance and insurance | 2 | |

| Business advisory services and standards | 4 | |

| Research and development; education and training | 2 | |

| Government departments | 7 | |

| Focus group discussion | District-level and national (Botswana Horticultural Council) farmers associations | 4 |

| Desktop review | Value chain studies on Botswana and other countries’ horticultural sectors; studies on horticulture in Botswana and elsewhere; Statistics Botswana International Merchandise Trade Statistics; Horticulture Unit—Production Trends | - |

| Strengths | Weaknesses | Opportunities | Threats |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal: positive attributes of the value chain | Internal: negative attributes of the value chain | External: positive attributes that can enhance the performance of the chain | External: negative factors that can prevent the efficient working of the chain |

| Variable | Category | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 72(71) |

| Female | 30(29) | |

| Educational Level | Primary | 6(6) |

| Secondary | 36(35) | |

| Tertiary | 44(43) | |

| Postgraduate | 14(14) | |

| Non-formal | 1(1) | |

| <30 | 7(7) | |

| Age | 30–39 | 29(28) |

| 40–49 | 32(31) | |

| 50–59 | 20(20) | |

| 60–69 | 9(9) | |

| >=70 | 2(2) | |

| Training received in horticulture | Yes | 57(56) |

| No | 45(44) | |

| Training in horticulture | Short course | 38(68) |

| Certificate | 12(21) | |

| Diploma | 3(5) | |

| Degree | 4(7) | |

| Production system (indicated in hectares planted) | Open field | 246(85) |

| Tunnel | 7(2.4) | |

| Shade net | 35(12) | |

| Hydroponics | 0(0) | |

| Greenhouse | 1(0.34) | |

| Membership of farmers’ group | Association | 35(50.72) |

| Cluster | 19(28) | |

| Cooperative | 4(6) | |

| Association and cluster | 2(3) | |

| Association and cooperative | 1(1) | |

| Association, cooperative, and cluster | 1(1) | |

| Source of water * | Borehole | 56(55) |

| River—perineal | 28(28) | |

| River—seasonal | 93(92) | |

| Dam—perineal | 3(3) | |

| Dam—seasonal | 4(4) | |

| Treated water | 1(1) | |

| Other | 3(3) | |

| Source of power for pumping water * | National grid | 30(29) |

| Solar | 25(25) | |

| National grid and solar | 9(9) | |

| National grid and engine/generator | 2(2) | |

| Petrol engine/generator | 23(23) | |

| Diesel engine/generator | 22(22) | |

| Irrigation technology * | Drip | 83(81) |

| Sprinkler | 32(31) | |

| Spray cubes | 10(10) | |

| Hose pipe | 23(23) | |

| Farrow | 3(3) | |

| Watering can | 16(16) | |

| Other | 5(5) |

| Strengths | Weaknesses | Opportunities | Threats |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Challenges Faced in Production | Weighting | Score | Rank | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Limited knowledge of horticultural production | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 300 | 12 |

| Pests and diseases | 33 | 16 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1085 | 1 |

| Limited land for expansion | 6 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 325 | 10 |

| Limited water for irrigation | 6 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 348 | 9 |

| Expensive inputs | 12 | 23 | 19 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 927 | 2 |

| Market access | 12 | 12 | 11 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 723 | 4 |

| Lack of storage | 2 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 433 | 6 |

| Weather conditions | 7 | 17 | 17 | 14 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 873 | 3 |

| Transport | 2 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 385 | 7 |

| Limited working capital | 6 | 4 | 8 | 9 | 15 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 614 | 5 |

| Lack of skilled labour | 2 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 391 | 8 |

| Lack of reliable labour | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 290 | 13 |

| Lack of funds to produce under controlled environments | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 310 | 11 |

| Other (e.g., wild animals, acidic water, high costs of fuel for irrigation) | 9 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 194 | 14 |

| Cause | Weighting | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | Score | Rank | |

| Causes of post-harvest losses | |||||||

| Lack of market | 60 | 20 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 396 | 1 |

| Poor storage | 18 | 27 | 10 | 8 | 0 | 244 | 2 |

| Poor transportation | 5 | 14 | 23 | 8 | 0 | 166 | 3 |

| Poor quality due to harvesting | 7 | 7 | 13 | 19 | 2 | 142 | 4 |

| Other (e.g., theft) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 5 |

| Causes of in-field crop losses | |||||||

| Pests | 54 | 21 | 13 | 3 | 0 | 399 | 1 |

| Diseases | 8 | 47 | 20 | 8 | 1 | 305 | 2 |

| Hailstorms/rain | 11 | 3 | 15 | 22 | 3 | 159 | 4 |

| Frost | 16 | 19 | 20 | 13 | 1 | 243 | 3 |

| Other (e.g., high temperatures, fungus) | 11 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 82 | 5 |

| Market Outlets in Order of Priority | Weighting | Score | Rank | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Retailers | 44 | 20 | 13 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 440 | 1 |

| Wholesalers | 8 | 20 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 209 | 5 |

| Hawkers | 28 | 27 | 22 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 408 | 2 |

| Public institutions (schools, hospitals, etc.) | 5 | 14 | 9 | 18 | 15 | 0 | 220 | 4 |

| Individuals | 11 | 16 | 32 | 18 | 10 | 0 | 348 | 3 |

| Other (e.g., hospitality industry) | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 6 |

| Market outlets paying better prices | ||||||||

| Retailers | 36 | 18 | 20 | 9 | 2 | 0 | 417 | 1 |

| Wholesalers | 3 | 16 | 14 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 182 | 5 |

| Hawkers | 23 | 30 | 14 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 383 | 2 |

| Public institutions (schools, hospitals, etc.) | 21 | 12 | 6 | 10 | 11 | 0 | 262 | 4 |

| Individuals | 14 | 18 | 27 | 12 | 10 | 1 | 339 | 3 |

| Other (e.g., hotels, lodges, and restaurants) | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Malope, P.; Madisa, M.E.; Solani, D.; Mabikwa, O.V. Opportunities and Constraints in the Horticultural Sector of Botswana: A SWOT Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3088. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073088

Malope P, Madisa ME, Solani D, Mabikwa OV. Opportunities and Constraints in the Horticultural Sector of Botswana: A SWOT Analysis. Sustainability. 2025; 17(7):3088. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073088

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalope, Patrick, Mogapi E. Madisa, Dynah Solani, and Onkabetse V. Mabikwa. 2025. "Opportunities and Constraints in the Horticultural Sector of Botswana: A SWOT Analysis" Sustainability 17, no. 7: 3088. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073088

APA StyleMalope, P., Madisa, M. E., Solani, D., & Mabikwa, O. V. (2025). Opportunities and Constraints in the Horticultural Sector of Botswana: A SWOT Analysis. Sustainability, 17(7), 3088. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073088