1. Introduction

Because of the recent focus on climate change in the media, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations are often linked to environmental preservation and climate change. However, the SDGs also address a wide range of objectives for societal advancement and individual well-being, where heritage and culture play significant roles.

The relationship between cultural infrastructure and economic levels is examined in this article, with particular attention to Goal 4: Quality Education and Goal 10: Reduced Inequalities. By fostering cross-cultural interaction, achieving these goals can significantly raise social capital. According to Bourdieu’s theory of social capital, access to and comprehension of cultural norms are fundamental components of social capital.

The purpose of this study is to determine the link between sustainable development (an economic component, GDP per capita, and a social component, poverty) and cultural infrastructure in the case of two countries, France and Romania, in the era of smart technologies and how multidisciplinary education can contribute to strengthening this link.

The significance of culture and cultural activities in mitigating inequality and enhancing education is paramount. People develop a greater awareness and regard for others from different backgrounds when they embrace multiple cultural experiences, which promotes inclusivity and respect. Cultural pursuits like music, theatre, and the arts give underrepresented voices a platform, bridging societal divides and allowing everyone to have their voice heard. By increasing accessibility and engagement with education, these activities also improve learning. For instance, adding visual arts, dance, and narrative to the curriculum can help make difficult subjects more approachable and understandable.

Besides developing critical thinking and creativity, students learn to empathize with others while participating in cultural activities. They begin viewing the world from other perspectives, which falls under solving problems and working collaboratively. In addition, exposure to different cultures can inspire students in new interests and professions that might expand their possibilities and open up options they would have never considered otherwise.

Ultimately, it is the enrichment of education, promotion of equity, and building of a more harmonious society of better understanding among all its members that is achieved by paying attention to culture. Valuing the diversity of cultures and embedding them into the process of education bring new educational settings in which each student feels at ease with one’s background (lifelong learning). This is not only important for individuals but also benefits communities and builds social cohesion.

Sustainable development has been defined since 1987 in the Brutland Report—Our Common Future [

1] as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”.

The British Academy [

2] defines cultural infrastructure as “the spaces, services, and structures that support the quality of life of a community, bringing people together and strengthening the social and cultural fabric”.

Cultural capital [

3] is defined as “non-economic assets that enable social mobility and confer social status, being transmitted through families, influencing educational outcomes, and perpetuating social inequalities”.

Cultural infrastructure and regional government priorities relate very closely to the questions of culture, education, and inequalities. It has the potential to contribute significantly to education and decrease social inequalities by making cultural experiences more accessible to everybody through the cultural infrastructure provided in museums, theatres, and community centers. Another relevant aspect is represented by the income levels of those people who really gain from such infrastructure.

Taking countries like France and Romania for comparison, one might ask whether income levels make any difference in the availability and use of cultural infrastructure. Should more cultural infrastructure be invested in low-income regions to increase equality and educational opportunities, or should such investments be concentrated in wealthier areas, such as where people are most likely to spend their money on cultural activities? Exploring these questions can reveal some good practices for using cultural infrastructure to support education and reduce inequalities. However, there are a few aspects that may contribute to differences in the development of cultural infrastructure, such as differences in the historical, social, and political context between the two countries with significant impacts on the development of cultural infrastructure. France has a strong long-standing cultural heritage and a well-implemented cultural policy system. Romania has a different history and is in the process of developing cultural infrastructure.

Decentralization means shifting power and control from a central authority to smaller, local units. This approach helps manage areas outside the main organization more effectively and efficiently. It also strengthens these areas by promoting democratic principles in public administration.

Decentralization is among the most globally widespread public sector reforms. Many countries have taken formal steps to empower local governments, typically with a mix of stated developmental and governance goals [

4]. This shift towards decentralization aims to enhance the responsiveness and efficiency of public service delivery by bringing decision-making closer to the local level. By redistributing powers and resources, administrative decentralization seeks to enable local governments to better address the specific needs and preferences of their communities. This approach not only promises to improve the quality and accessibility of services but also to foster greater local accountability and participation in governance. As a result, decentralization is increasingly viewed as a key strategy for achieving both developmental goals and improved governance outcomes in diverse political and administrative contexts. Administrative decentralization seeks to redistribute the authority, responsibility, and financial resources for providing public services between different levels of government [

5].

The implementation of decentralization laws in France and Romania has had a strong impact on the administration and distribution of cultural infrastructure. As a result of the transition from centralized toward localized governance, these legal frameworks highlight the importance of local governments in cultural management. This common dedication to decentralization offers a solid foundation for contrasting the ways in which cultural infrastructure supports sustainable development in various local contexts.

The decentralization legislation in France, especially the changes of 1982 and 1983, laid the groundwork for the transfer of authority and funds from the state to local government entities [

6]. This legislative framework attempted to address disparities in a few areas, including culture. France invests an average of 1.5% [

7] of its GDP in the cultural sector. By giving local governments the authority to manage cultural infrastructure, France encourages a more equal allocation of cultural resources, which supports cultural variety and accessibility at the regional level and is consistent with larger sustainable development objectives.

The framework law on decentralization represents a significant advancement in the transfer of financial and administrative responsibilities from the national government to local governments and even the private sector in Romania. Utilizing the potential of culture and cultural diversity for social cohesion and welfare is the focus of Romania’s approach. This legal framework with the national strategy for cultural and creative industries also highlight the multifaceted role of cultural infrastructure in sustainable development by promoting cultural creativity in innovation, economic growth, job creation, and education [

8]. The decentralization laws of both nations support local economic growth, cultural variety, and accessibility, all in line with the broader objectives of sustainable development in the era of smart technologies and digital progress of the EU Member States. An examination of the operationalization of these policies in several contexts, including France and Romania, provides insights into the efficacy of cultural infrastructure as a tool for sustainable regional development.

Since 2014, the European Commission has been monitoring Member States’ digital progress through the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) reports. Since 2023 and in line with the 2030 Digital Decade Policy Agenda, the DESI is integrated into the Digital Decade Progress Report and used to monitor progress towards digital goals [

9].

To answer the objectives of this study, we formulated the following research questions:

- Q1.

What is the link between sustainability (an economic component, GDP per capita, and a social component, poverty) and cultural infrastructure?

- Q2.

What are the main themes addressed in the specialized literature?

- Q3.

What are the main policy recommendations and practical solutions that the authors of the article offer for decision-makers?

This paper has in its structure the Introduction section describing the subject of the research topic, i.e., cultural infrastructure as a vector of sustainable development in the current context of sustainability and smart technologies with a focus on France and Romania; a Materials and Methods section detailing the research objectives on the cultural infrastructure of France and Romania; a Results and Discussion section related to the two countries; and a Conclusions section.

3. Results and Discussion

To answer the objectives of this study, we formulated the following research questions:

Q1. What is the link between sustainability (an economic component, GDP per capita, and a social component, poverty) and cultural infrastructure?

We present the results from the linear regression analysis that were conducted to establish the relationship between GDP per capita and cultural infrastructure. The analysis was performed in Excel, and the results present the significance and power of the associations. It contains some key metrics regarding the regression coefficients, R-squared value, and

p-values so as to obtain an all-round understanding of the model’s performance and its power of prediction. We present the major results of our analysis below (

Figure 1).

The model explains approximately 32.14% of the variance in the cultural expenditure of local governments based on the GDP per capita. This simply means that by itself, GDP per capita, as an explanatory factor, is relatively influential in association with cultural expenditure, but there would be other explanatory factors to account for the remaining 67.86%. As GDP per capita increases, more cultural expenditure by local governments is equally invoked. The existence of a relationship is attested by the t-value being not zero. But, this is not a strong relationship, as its magnitude of slope is very small. The R square value is 0.3214; hence, the GDP per capita does not predict the cultural expenditure well, indicating a lot of variability that this model could not manifest. This might well be because the higher the BDP per capita of the region, the lesser the investment in the regional cultural infrastructure, which may be due to other priorities in that sector.

The regression analysis for France (poverty and cultural infrastructure) reveals a moderate relationship (

Figure 2) between the independent and dependent variables, with a multiple R value of 0.60, indicating a positive correlation.

The R square value of 0.36 suggests that approximately 36% of the variation in the dependent variable is explained by the independent variables, while the Adjusted R square value of 0.32 accounts for the number of predictors, showing a slightly lower but still moderate explanatory power. The standard error of 28.94 reflects the average deviation of observed values from the regression line, though its significance depends on the scale of the dependent variable. Most importantly, the model is statistically significant, as indicated by the significance F value of 0.0085 (p < 0.05), meaning that the independent variables collectively have a meaningful impact on the dependent variable. However, with 64% of the variance still unexplained, other influential factors not included in the model may also play a role.

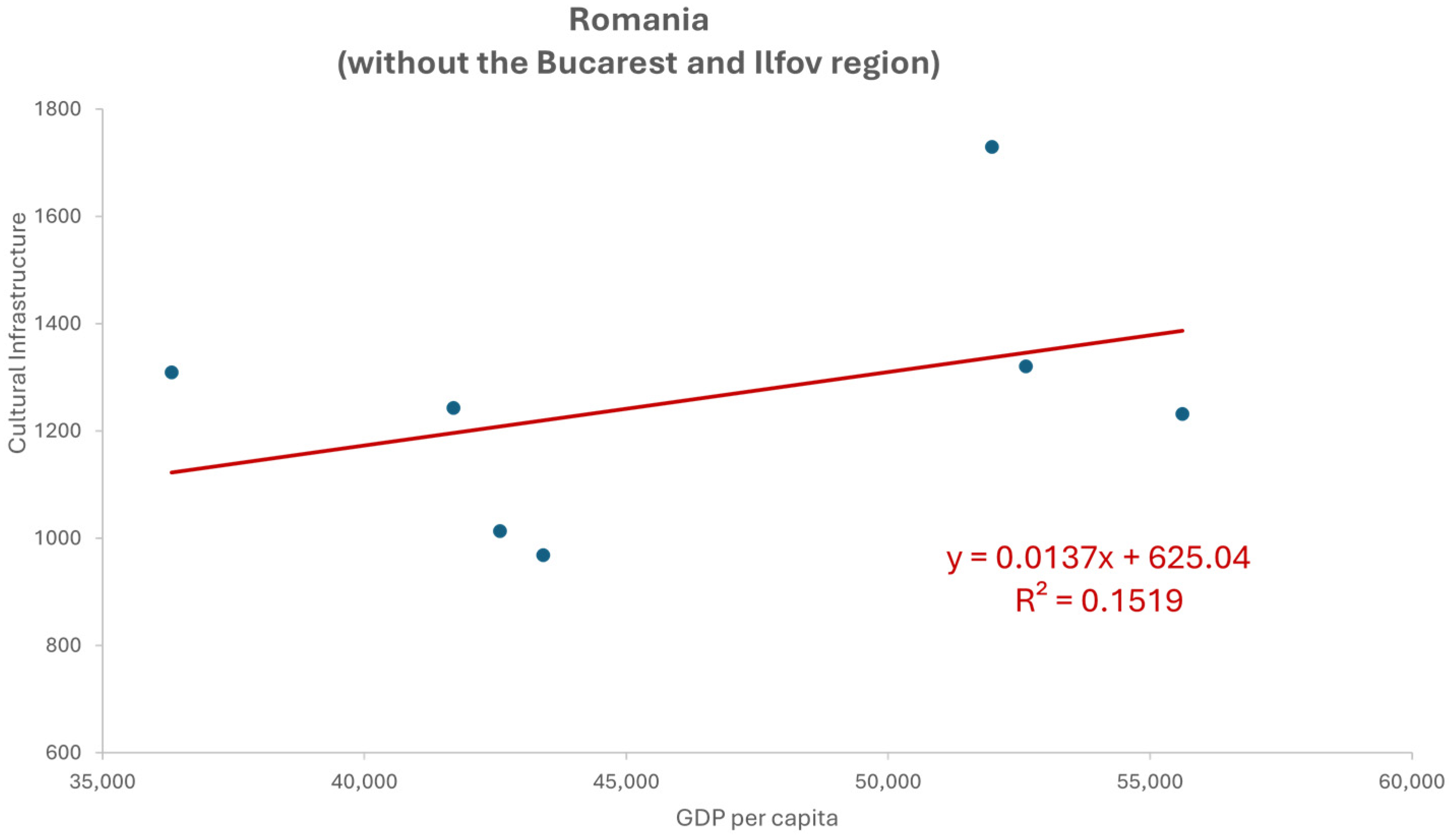

The model in

Figure 3 (results for Romania) explains about 63.39% of variance in cultural infrastructure based on the GDP per capita; so, there is quite a strong explanatory power.

The slope is negative (−0.0124), indicating that the higher GDP per capita, the lower the cultural infrastructure. The relationship is meaningful despite the small magnitude of the slope. With an R square value of 0.6339, GDP per capita is a significant predictor of cultural infrastructure; however, 36.61 percent of the variability is left without an explanation by the model. This could be interpreted to mean that higher per capita GDP regions might spend less on cultural infrastructure due to priorities placed elsewhere or due to them having adequate cultural infrastructure. The high explanatory power would, therefore, indicate that GDP per capita is an important factor explaining cultural infrastructure, although other variables should be put into consideration to fully explain the relationship.

Something in this regression analysis unbalances the results, which can be clearly observed in the graph. The circled point at the lower right extremity of the graph represents the situation of the Bucharest and Ilfov region. Being the largest city and, more importantly, an economic engine of the country, it might be misleading—as the generated GDP per capita is much higher than that in other regions, while the total superficies of this region is relatively small compared with the others; so, probably it may be normal to have a smaller cultural infrastructure. In order to correct this variable, another analysis has been run without considering this region.

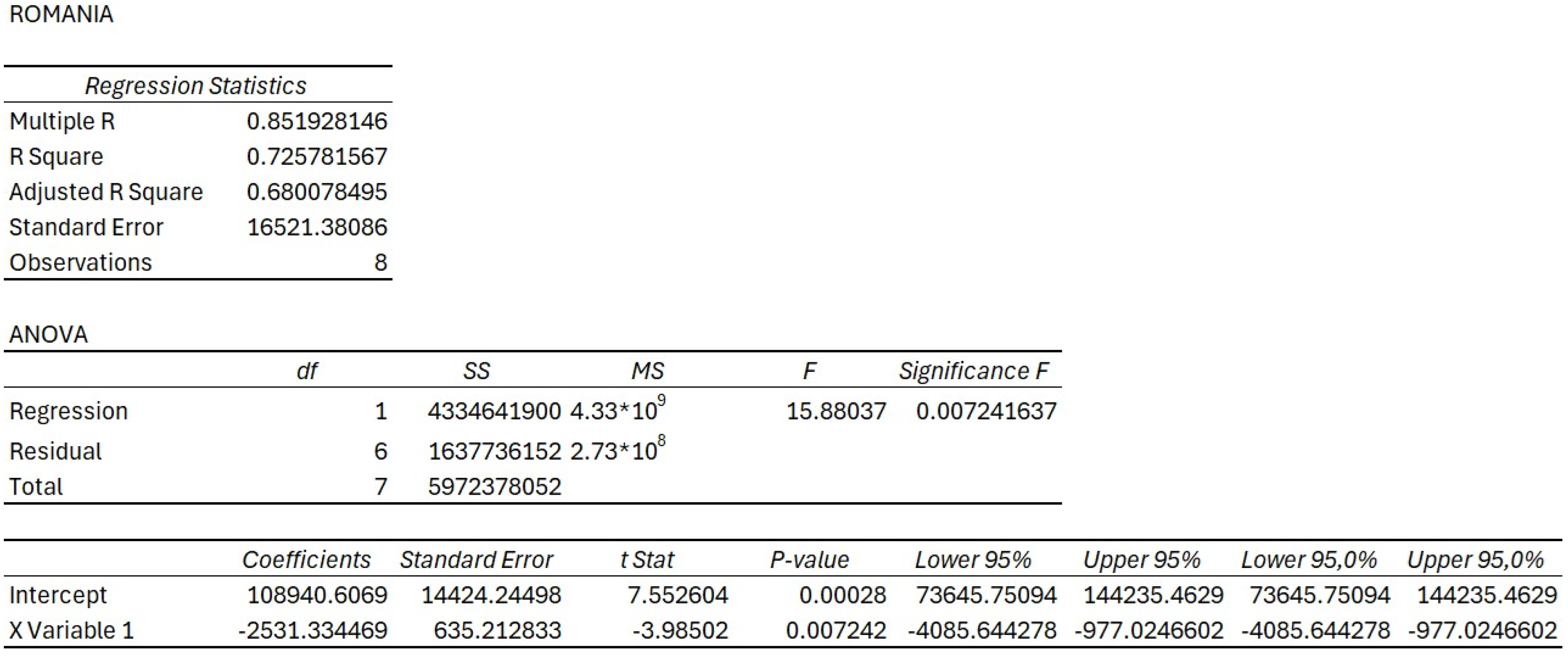

The model (

Figure 4) accounts for around 15.19% of the variation in cultural infrastructure as a function of GDP per capita. The slope, 0.0137, is positive, indicating that cultural infrastructure tends to increase with increasing GDP per capita.

However, the relationship is not that strong, since the magnitude of the slope is small. At this R square value of 0.1519, the GDP per capita is not that strong a predictor of cultural infrastructure. This means that it has low predictive power with respect to cultural infrastructure based on the GDP per capita alone.

The regression analysis (

Figure 5) indicates a strong relationship between the independent and dependent variables, with a multiple R value of 0.85, suggesting a high positive correlation.

The R square value of 0.73 shows that approximately 73% of the variation in the dependent variable is explained by the independent variables, while the adjusted R square value of 0.68 accounts for the number of predictors and confirms the model’s strong explanatory power. The model is also statistically significant, as evidenced by the significance F value of 0.0072 (p < 0.05), meaning that the independent variables collectively have a meaningful impact on the dependent variable. With only 27% of the variance left unexplained, this model provides a stronger predictive capacity compared to the previous one, though additional factors may still contribute to the outcome.

The decentralization laws of both nations support local economic growth, cultural variety, and accessibility, all of which are in line with the broader goals of sustainable development in the era of smart technologies and digital progress of the EU Member States.

These interpretations underline the fact that even though there might be some weak positive relationship between cultural infrastructure and GDP per capita, it is not strong enough to predict simply on the basis of the GDP per capita. Other factors have to be explored so as to have a fuller understanding of what drives the development of cultural infrastructural facilities.

One of the very first elements that we can apply to this model is the Bucharest exception, which completely changed the tendencies of this phenomenon. In fact, the high explanatory power of this regression may support that GDP per capita is one of the main elements in explaining cultural infrastructure; however, other variables should also be taken into account in order to gain a deeper understanding of their relationships. These findings indicate that a more complete model with other variables is needed to explain the variation in cultural infrastructure in the absence of control for this region.

For instance, the frequency of participation in public cultural consumption, which applies to every cultural unit that was taken into the analysis, shows that Romanians are not heavy consumers of cultural goods and services (

Figure 6), at least in the public sphere [

25].

This may raise the problem to a whole different stage, where the questions are more about the consumer behavior of Romanians regarding cultural goods and services and the lack of incentives to consume being justified by a deeper social cause and not by the income level or cultural infrastructure. “The science of taste and cultural consumption begins with a transgression that is in no way aesthetic: it has to abolish the sacred frontier which makes legitimate culture a separate universe, in order to discover the intelligible relations which unite apparently incommensurable choices, such as preferences in music and food, painting and sport, literature and hairstyle” [

26]. It is though difficult to assess the impact of the cultural infrastructure by itself into the obtentions and development of cultural capital to tackle inequalities.

The other fundament of this study aims to show that access to culture can enhance education. Without official data on available on the topic of scholar abandonment by region, we have to take the world of media outlets and their private investigation. Apparently, Regiunea Centru is the one with the higher scholar abandonment in 2020, raising to 4.45% [

27]. From our data, it scores second highest in terms of cultural infrastructure and third in terms of GDP per capita. This seems contradictory, as we would not normally expect this kind of situation based on both of our variables. This may be explained by the huge difference between life conditions and opportunities in rural and urban areas of the region.

These opposite results to the second and third analyses underline how dramatic an effect a certain region can have on overall trends. As can be seen by removing the Bucharest and Ilfov region, its data may have affected the original analysis, biased the relationship, and explained the power of the model. It may be that in a full dataset, more complex dynamics are at work in the negative correlation, such that high economic wealth [

28] might relatively decrease cultural investment due to shifting priorities or saturating cultural infrastructures. This is hidden in this instance by the deletion of such information, and instead, is a more general—and fundamentally weaker—positive correlation made overt, indicating that when most extreme-impact regions, such as Bucharest and Ilfov, are discarded, this correspondence appears less extreme and open to a greater range of more complex influences. Several constraints are found within the analyses of the relationship between GDP per capita and cultural infrastructure. Excluding data from the Bucharest and Ilfov region may introduce a selection bias as—due to it being unique in its economic and cultural characteristics—it has a very strong ability to sway the general trends in a way that might distort the result. Both the models are linear; this can be too simplistic to explain the complex and often nonlinear relationship of GDP per capita with cultural infrastructure while missing other key variables, such as local policy and historical factors. The R square values show that most of the variability in cultural infrastructure cannot be explained by GDP per capita alone, which is why one needs to add more explanatory variables.

Compared to other studies in the literature that also used linear regression mentioned by Titko et. al., the dataset is represented by nineteen explanatory variables and two dependent variables, which are proxies for the Sustainable Development Goals. The data were collected from 27 European countries for the period of 2011–2020.

However, since 2014, the European Commission has been monitoring Member States’ digital progress through the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) reports. From 2023 onwards and in line with the 2030 Agenda (2030 Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals) on the Digital Decade, the DESI is integrated into the Digital Decade Progress Report and used to monitor progress towards the digital goals. From 2014 to 2022, the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) summarized indicators on Europe’s digital performance [

29] and tracked the progress of EU countries (

Figure 7).

In

Figure 7, it can be seen the differences in the rankings of the two countries according to the DESI index from the EU average. Thus, France ranks above the EU average, while Romania ranks last in the DESI ranking for 2022.

France ranks 12th out of 27 EU Member States in the 2022 edition of the Digital Economy and Society Index. Thanks to a sustained effort to support digitization, France has outperformed in recent years, progressing more than expected. However, the country is not yet among the digital frontrunners. In the coming years, France will accelerate progress towards digital transformation to achieve the Digital Decade goals [

30]. The digital transformation of the French economy and society is underpinned by the Recovery Plan, with a generous contribution of around EUR 40 billion. For 2030, France has launched a strategic plan to strengthen its technological sovereignty by greening the economy and stimulating innovation. Initiatives are underway in several areas of activity including culture.

Romania ranks 27th out of the 27 EU Member States in the 2022 edition of the Digital Economy and Society Index. The country lags behind on a number of indicators of the human capital dimension, with a low level of basic digital skills compared to the EU average. However, Romania maintains its top spot in the indicators: the share of female ICT specialists in the workforce (2nd place) and the number of ICT graduates (4th place). A significant change in the pace of Romania’s digital skills readiness is essential if the EU is to achieve the 2030 Digital Decade target for digital literacy and ICT specialists. Romania performs relatively well in connectivity, the dimension for which it scores best, but performs less well in the other three sections of the DEDI index, namely, human capital, digital technology integration, and digital public services, including in the area of cultural infrastructure.

Q2. What are the main themes addressed in the specialized literature?

Viewing the map (

Figure 8) indicating the density of the keywords chosen by the authors, culture, education, and sustainable development (CEDD), in a simple query of the Web of Science (WoS) database on 15 August 2024, shows that for a minimum of five occurrences of the 2743 words selected with the WOSviewer software version 1.6.20 [

31], 74 out of the 144 selected articles meet the threshold of occurrence.

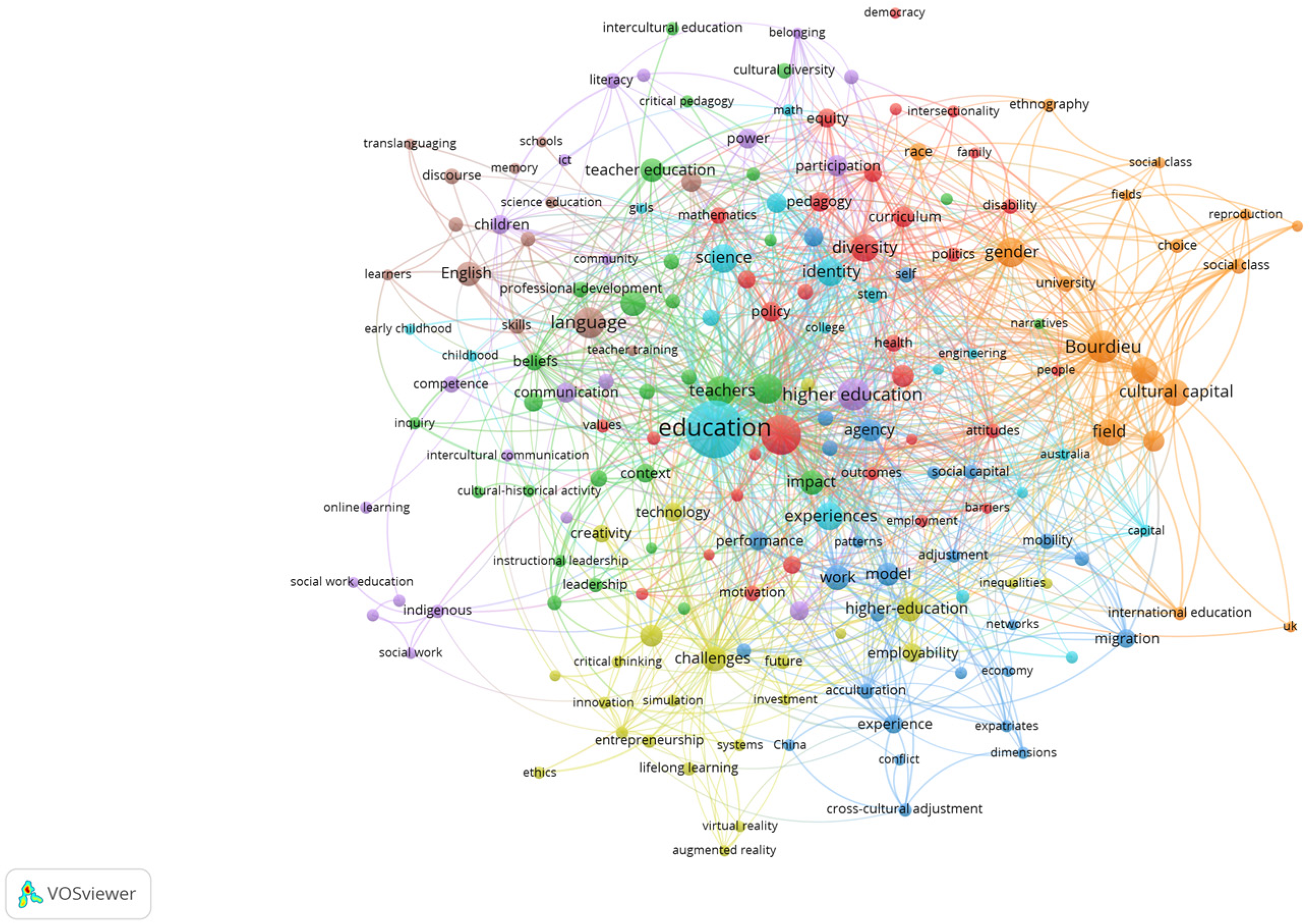

With a bibliometric analysis, it is possible to highlight the occurrences of the keywords but also the strong links made by them (

Figure 9). At a minimum of five occurrences out of the 3511 words selected with the WOSviewer software from the 144 selected articles, 182 words meet the occurrence threshold. Thus, the word education appears 124 times and achieves 394 links, cultural equity appears 27 times and achieves 97 links, cultural appears 25 times and achieves 78 links, inequality appears 17 times and achieves 77 links, etc. The main words that highlight the analysis nuclei are higher education, Bourdieu, diversity, teacher education, culture, cultural diversity, professional development, equity, creativity, etc.

Most articles were published in journals such as

Education Sciences,

Frontiers in Education,

British Journal of Sociology,

Cultural Studies of Science,

Higher Education,

Social Work Education,

Revista Românească Pentru Educație, etc., as shown in

Figure 10.

In addition, our study also bases its research methodology on a bibliometric analysis in order to map and emphasize the importance of the created field of culture, education, and sustainable development (CEDD).

The bibliometric analysis develops in this paper the conceptual structure that identifies the main themes emerging from the analyzed sample. The analysis of the co-occurrence of terms identifies the frequency and links between them in the selected sample articles, highlighting specific topics. From the total of 18,788 terms, the selection using VOSviewer from the Web of Science database involved excluding terms with a low relevance score from the 458 terms meeting a threshold of 10 occurrences, resulting in a total of 275 terms. The grouping of terms highlights four research themes (

Figure 11) addressed in four clusters.

The 144 articles selected with VOSviewer were analyzed by the study authors using the content analysis method. Each author was assigned 18 articles for analysis. At the end of the study, the four research themes were outlined, as presented below.

The red zone (94 items) contains terms such as regions, cultural heritage, cultural heritage sustainability, communication, topic, traditions, initiatives, services, tourism, promotion, potential, improvement, important role, history, globalization, effectiveness, educational system, creation, creativity, cultural differences, young person, cultural norms, cities, innovation, measure, mechanism, methodology, motivation, new knowledge, etc. The sustainability of cultural heritage [

32] is a complex, rarely measured topic due to the lack of indicators of the sustainability of universal heritage. The authors propose a set of cultural heritage sustainability indicators, because in the last decades, “the notion of ‘culture’ has emerged as the fourth pillar of sustainable development” [

33]. Cultural heritage is considered as a tool for sustainable development, certainly for the developing world. According to Ölçer Özünel, E. [

34], among the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, there is no direct heading related to culture, but it is obvious that culture is at the center of the goals. Crowdsourcing of cultural heritage [

35] has emerged as a promising novelty to address the challenges of digitization and preservation of cultural heritage, contributing to the SDGs of cultural preservation and digital inclusion. The rapid development of digitization, in light of the regulation of complex management processes, requires the establishment of a legal, sustainably regulated framework in accordance with the highest standards of cultural heritage protection [

36]. In the context of the continuous digitization of society and the dimensions of inclusiveness, equality, citizens’ needs, sustainability, and quality of life are increasingly important as driving forces for cities to become smart [

37]. Transforming a city with cultural heritage into a smart city requires efforts that go beyond smart ICT (Information and Communication Technology) implementation into social sustainability issues. Authors [

38] have explored the integration of augmented reality (AR) technology in cultural heritage tourism, especially its influence on the development of the heritage responsibility behaviors of tourists. There is consensus on the importance of local identity and cultural diversity in the sustainability discourse, including community resilience. Cultural policies are essential to enable sustainability goals [

39] and the realization of smart cities. On the role of culture and cultural heritage in the development and construction of smart cities [

40], as well as the legal framework that facilitates or promotes their incorporation in the new organizational models that have been launched, A. Borda and J. P. Bowen [

41] have spoken. Sustainable and smart cities are a new target for urban development [

42]. Public authorities need to identify and develop sustainable strategies to increase the performance of their city and ensure that it lasts over time. Information and Communication Technology (ICT) contributes greatly to this goal in the era of digitalization. The preservation, protection, and accessibility of cultural heritage have become essential elements with the rapid advances of globalization and financial modernization efforts that constantly threaten historical artifacts and sites around the world. The emergence of the metaverse [

43], which has immersive and interactive capabilities, represents a new, sustainable approach to the protection, conservation, and promotion of cultural heritage. Exploring the potential of metaverse applications in the digitization of cultural heritage can make possible virtual reconstructions, educational expansion, global accessibility, and the sustainability of cultural heritage. A series of challenges and opportunities associated with the virtual preservation and protection of tangible and intangible cultural heritage are highlighted, including issues of representation, authenticity, and sustainability. Furthermore, the impact of metaverse applications on cultural education on the one hand and on public engagement on the other hand can be assessed. The foundations are laid for the development of innovative strategies in the digital age for the preservation of cultural heritage. Best practice solutions and guidelines are highlighted for optimizing and cost-effective applications of the metaverse in the preservation of cultural heritage around the world.

The green zone contains 78 items, such as assumption, connection, complexity, child, class, COVID, crisis, conversation, cultural historical activities, cultural diversity, inclusion, globalization, identity, instructor, educator, cultural and intercultural competences, lessons, linguistic diversity, literature, pedagogue, progress, reflection, reform, story, storytelling, vision, voice, suggestion, site, reflection, etc. The problem of the sustainability of many original products of intangible cultural heritage stems from the reduction in the number of folk craftsmen. This is also the case for craftsmen who weave bamboo baskets. New technologies for designing bamboo baskets such as 2D to 3D mapping have been analyzed [

44]. These intelligent technologies allow designers to analyze and design digital models. Other authors [

45] state that the integration of cultural heritage in education facilitates the introduction of new learning styles based on critical thinking, experiential learning, and intercultural collaborative learning. Digital technologies make education more accessible and facilitate innovative hybrid models within sustainable education. According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) culture [

46] provides the transformative dimension to ensure the process of development of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. As one of the key enablers in the implementation of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, culture provides a people-centered and lifelong learning approach that cuts across a range of policy areas and, thus, in the context of quality education, promotes human resource development for cultural and environmental sustainability. A study analyses the cultural identity of students and helps the younger generation [

47] to preserve the values inherited from their ancestors throughout their lives. The most appropriate solution identified in the Catalan public and private sectors [

48] regarding the inequality of women’s working conditions in the Catalan cultural sector was compliance with the law on the recognition of equal pay for equal work between Catalan women and men. In the context of smart technologies, the introduction of games into experiential learning can increase young people’s interest in the cultural heritage brought by historical sites, artifacts, and cultural traditions. K12 students [

49] evaluate the impact of games on cultural heritage in terms of learning capacity. The game design process is a complete and complex one based on an automatic generation of the game maze using a formal description, topology, learning methodology, and evaluation of the game experience. Maze video games, as part of digital literacy, are the most appropriate tools for learning, accessibility, protection, and preservation of cultural heritage for students of all ages.

The blue zone includes 71 items, such as academic, faculty, agenda, barriers, benefits, Bourdieu, capital, conceptual framework, cultural capital, cultural practices, original values, design methodology approach, employability, inequality, master, manager, organization, barriers, partnerships, practical involvement, qualitative studies, recruitment, responsibility, professionalism, social capital, supervisor, transition, variety, jobs, etc. The creation of sustainable cities [

50] is the main objective of urban development strategies in the context of sustainability. In addition, they acquired [

51] teaching skills that promoted quality education and contributed toward two of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), in particular: SDG 4 “Ensure inclusion and equity for quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” and SDG 11 “Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable”. The importance of the cultural economy [

52] has led urbanism to a new stage in the direction of sustainability, ecology, and energy efficiency. Culture is the engine for everything that makes a city creative and sustainable [

53]. Popular music [

54] and its heritage are the key drivers for urban regeneration in small towns. The identification and inventory of avifauna [

55] present in the area of archaeological sites around the Acropolis in Greece underlines the importance of these areas as a biotope for wildlife in the historic center of Athens, the largest city in Greece. A study [

56] introduces to the literature a robust multidimensional framework for assessing the intelligence of Italian cities. Some studies [

57] have analyzed the roles of social and cultural sustainability as key factors shaping smart urban development in some Arab regions and highlight how cultural aspects are integrated into the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Cities. Other studies analyze [

58] sustainable tourism practices in specific regions of the South Caucasus to map the synergies and trade-offs between sustainable tourism practices and sustainable development goals. The authors of some studies [

59] present the benefits brought by urban trees to the city community, such as carbon capture and greenhouse gas reduction, regulation of air and water quality in the urban environment, and pest and disease control. The issue of air pollution from urban street areas [

60] poses a serious risk to public health, especially in highly populated areas. Improving accessibility [

61] and correlating social media data with traditional methods can lead to improved cultural heritage conservation strategies and help sustainable urban development by promoting stronger and more prominent identity values in cities.

The yellow area includes 32 items, such as achievements, associations, careers, behavior, equality, gender, investigation, boundaries, representation, respondent, science, future research, objectives, women, young, sample, network, infrastructure, questionnaire, etc.

The relevance of exploring green rural, cultural, and ecological tourism in Europe is an extremely important topic that offers tourists the opportunity to enjoy nature, culture, rural landscapes, and clean air; to interact with locals and their crafts; and to participate in authentic rural life with traditions and customs [

62]. Green rural tourism can facilitate cultural exchange between tourists and locals [

63]. A balanced correlation that takes into account the needs of cultural infrastructure, environmental elements, traditional cultural aspects, and the participation of local communities are the key elements of the sustainable development of green rural, cultural, and ecological tourism in Europe [

64]. The authors of a study [

65] tested a hypothesis about the contribution of culture to sustainable development through the relationship between culture-related indices and the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. Research on green, cultural, and ecological rural tourism in Europe contributes to the development of the tourism industry and has an important impact on the socio-economic development [

66] and the preservation of the natural and cultural heritage of the regions. The UNESCO Convention on the Intangible Cultural Heritage dates back to 2003 and has been signed by 178 countries. The greatest impact of the Convention was the inclusion of the International Council of Museums in 2007 in the definition of museums by intangible cultural heritage [

67]. A study in the literature [

68] indicates a clear fragmentation of the plan in Nepal for the cultural configuration and the efforts to accelerate cultural infrastructure; thus, a tripartite strategic model for tourism development is needed in order to achieve sustainable economic growth, especially in developing countries. Culture [

69] is a specifically human activity that enriches the lives of citizens and contributes to economic growth through employment and social cohesion, thus helping to sustainably transform urban and rural areas in Slovakia by promoting sustainable tourism but also in other areas [

70]. Other studies [

71] explore the dynamic links between social capital, livelihoods, and tourism development in a region of Pakistan [

72], with a focus on indigenous social capital influenced by cultural trends [

73]. The authors of a study [

74] found a series of factors that are positively and negatively [

75] influenced by the use of cultural heritage [

76] in the socio-economic development of a region. Inclusive growth [

77] is that economic growth that is accompanied by a reduction in social inequalities in different dimensions through different channels and factors that can favor access to cultural heritage [

78].

Q3. What are the main policy recommendations and practical solutions that the authors of the article offer for decision-makers?

Promoting the development of cultural infrastructure in regions with different economic levels requires tailored policies that address local economic conditions, funding availability, and community needs. Various policy measures can effectively promote cultural infrastructure development across regions. Public–private partnerships, such as the UK’s Creative Enterprise Zones, encourage collaboration between local governments and businesses through tax incentives and co-funding opportunities. European Union structural funds, like the European Regional Development Fund, have revitalized industrial heritage sites in Poland, demonstrating how targeted financial support can transform cultural landscapes in disadvantaged areas. The decentralization of cultural institutions, exemplified by France’s Musée du Louvre-Lens, fosters economic growth by encouraging major museums and theaters to establish branches in struggling regions. Additionally, cultural tax incentives and grants, such as Canada’s Cultural Spaces Fund, provide direct funding and tax reductions for arts and heritage projects in underdeveloped areas. Lastly, community-led cultural development, inspired by Brazil’s Favela Cultural Movement, highlights the importance of grassroots initiatives by supporting local artists through funding and training programs, ensuring inclusive and sustainable cultural growth.

Several measures can be implemented by local governments to balance economic development and cultural investment. As already implemented in different cities and argued in the academic literature, clustering cultural institutions in certain districts generates spillover economic benefits [

79]. For example, in Nantes, France, several industrial sites, such as the ancient LU Biscuits factory and the Naval Chartiers, have been transformed into cultural hubs. Also, in Barcelona, Spain, with the creation of the 22@ Innovation District, the city transformed a former industrial area into a hub for technology, startups, and culture.

The authors of this article propose a practical solution applicable to the field of culture for resilience and sustainability (

Figure 12) in both countries, but especially in Romania, to reduce the gap with France. Moreover, this practical solution helps decision-makers to integrate smart technologies into different aspects of cultural infrastructure, such as improving the conservation of cultural heritage, improving the accessibility of cultural activities, and promoting cultural education.

The interaction of intelligent technologies interacting and helping, nowadays, in a series of activities found in the cultural area makes the emergence of AI, artificial intelligence, through a series of uses, from natural language processing to machine translation into various languages of international circulation, received by several tourists as a great plus in terms of international circulation.

The use of smart technologies now creates the possibility to interact very easily with a number of institutions related to the cultural area, from museums and theaters, to cinemas and even participation in a number of festivals promoted online and easily found by tourists via the internet.

The solution proposed by the authors of this article is based on the use of an ERP system, in this case SAP, which is managed by the municipal company of a city and which has under its subordination several institutions that promote and produce cultural acts aimed at involving the local public, as well as the one who is on vacation and visiting our country.

The main idea is that those who want to best promote what they have as objects of activity in the cultural area, including theater, art, cinema, museums, etc., will have to create an account and upload various promotional materials designed to attract tourists from various places around the globe. The application will store all these materials and make them available to tourists very easily via the internet on web pages populated with data from the ERP application. Moreover, tourists will make reservations to be used to see many cultural events in our country and beyond. However, there are also some disadvantages to using smart technologies due to access, with urban areas having an advantage over rural areas.

The promotion by governments of countries of packages to help the population to acquire smart technologies, from smart phones, tablets, etc., to smart TVs, would be auspicious and useful in the interplay between culture, well-being, and the big picture of a sustainable ecosystem. The smart architecture promoted by the authors of this scientific article will allow the cultural activities existing in a location to be highlighted, but, moreover, the possibility to have an overview of a series of events that will take place in a period, where the use of smart technologies is a good opportunity to interconnect smart technology with culture.

It can be seen that a number of elements have been utilized, from the use of cloud or on premise storage environments, intelligent communication channels with the likes of SAP Fiori Launchpad (provides access to the application using a web page), SAP CoPilot (digital assistant for SAP users), and SAP CoPilot working as a chatbot integrated into S/4HANA.

It uses Natural Language Processing (NLP) to allow users to interact with the ERP system via voice or text commands, automating tasks and providing contextual information; SAP Intelligent RPA (Robotic Process Automation) integrates software robots that automate repetitive processes.

They can be used to retrieve data or respond to requests, thus automating communication between departments or even with external systems, e-mail, SAP Conversational AI, etc., up to modeling business processes for sales and purchasing [

80]. This application can be installed on any smart device, i.e., smart phones, tablets, computers, etc. This way of approaching the interaction between culture and those who want to participate in events of all kinds belonging to this segment of activity using smart technologies [

81] leads to progress and facilitates the possibility of more detailed and rapid information.