Sustainable Development of Soft Skills with the Purpose of Enhancing the Employability of Engineering Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Framework

1.2. Research Questions

- -

- What soft skills do students consider to be relevant in order to get a job in their field?

- -

- What can be done to improve the employability of engineering students within ESP classes?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.1.1. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale

2.1.2. Johari Window Questionnaire

2.2. Research Instruments

3. Results

3.1. Outcome 1: Identification of the Soft Skills Maximizing the Career Success of Engineering Students

3.2. Outcome 2: Design and Validation of the ESP Course

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale

Appendix B. Johari Window Test

References

- Hirudayaraj, M.; Baker, R.; Baker, F.; Eastman, M. Soft Skills for Entry-Level Engineers: What Employers Want. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvinenko, V.S.; Petrov, E.I.; Vasilevskaya, D.V.; Yakovenko, A.V.; Naumov, I.A.; Ratnikov, M.A. Assessment of the role of the state in the management of mineral resources. J. Min. Inst. 2023, 259, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikeshin, M.I. Technoscience, education and philosophy. Gorn. Zhurnal 2022, 11, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretschmann, J.; Plien, M.; Nguyen, T.H.N.; Rudakov, M.L. Effective capacity building by empowerment teaching in the field of occupational safety and health management in mining. J. Min. Inst. 2020, 242, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmos, A.; Holgaard, J.E.; Routhe, H.W. Understanding and Designing Variation in Interdisciplinary Problem-Based Projects in Engineering Education. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyebanji, D.J. The Spread of English Language in Asian Countries: A Review Paper. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 2024, 5, 3648–3651. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382871392_The_Spread_of_English_Language_in_Asian_Countries_A_Review_Paper (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Knight, P.T.; Yorke, M. Learning, Curriculum and Employability in Higher Education; Routledge Falmer: London, UK, 2004; pp. 203–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.; Knowles, V. Graduate recruitment and selection practices in small businesses. Career Dev. Int. 2000, 5, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Liang, F.; Guo, H.; Li, B. Research on Personal Skills That Architects Should Focus on Improving in Professional Career Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelha, M.; Fernandes, S.; Mesquita, D.; Seabra, F.; Ferreira-Oliveira, A.T. Graduate Employability and Competence Development in Higher Education—A Systematic Literature Review Using PRISMA. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J.; De Grip, A. Training, task flexibility & employability of low-skilled workers. Int. J. Manpow. 2004, 25, 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Mainga, W.; Murphy-Braynen, M.B.; Moxey, R.; Quddus, S.A. Graduate Employability of Business Students. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukulska-Hulme, A.; Wise, A.F.; Coughlan, T.; Biswas, G.; Bossu, C.; Burriss, S.K.; Charitonos, K.; Crossley, S.A.; Enyedy, N.; Ferguson, R.; et al. Innovating Pedagogy 2024: Open University Innovation Report 12; The Open University: Milton Keynes, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Petruzziello, G.; Chiesa, R.; Mariani, M.G. The Storm Doesn’t Touch me!—The Role of Perceived Employability of Students and Graduates in the Pandemic Era. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, R. Six Must-Have Soft Skills for Freshers in 2023. The Economic Times, 1 June 2023. Available online: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/jobs/fresher/six-must-have-soft-skills-for-freshers-in-2023/articleshow/100518650.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Bui, B.C.; Gonzalez, E.M. Obtaining Academic Employment Within the U.S. Context: The Experiences of Strugglers. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazhin VYu Issa, B. Influence of heat treatment on the microstructure of steel coils of a heating tube furnace. J. Min. Inst. 2021, 249, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrokhina, K.V.; Trofimets, V.Y.; Mazakov, E.B.; Makhovikov, A.B.; Khaykin, M.M. Development of methodology for scenario analysis of investment projects of enterprises of the mineral resource complex. J. Min. Inst. 2023, 259, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharlamova OYu Zherebkina, O.S.; Kremneva, A.V. Teaching Vocational Oriented Foreign Language Reading to Future Oil Field Specialists. Eur. J. Contemp. Educ. 2023, 12, 480–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabzadeh, A.R.; Long, J.; Saini, G.; Zeadin, M. Engineering Student Experiences of Group Work. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrkov, A.G.; Makhovikov, A.B.; Tomaev, V.V.; Taraban, V.V. Priority in the field of nanotechnology of the Mining University in St. Petersburg—A modern center for the development of new nanostructured metallic materials. Tsvetnye Met. 2023, 8, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skornyakova, E.R.; Vinogradova, E.V. Fostering engineering students’ competences development through lexical aspect acquisition model. Int. J. Eng. Pedagog. 2022, 12, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Li, W.; Zhang, H. Career Adaptability as a Strategy to Improve Sustainable Employment: A Proactive Personality Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.F.B.; Cipolla, C.M. Critical Soft Skills for Sustainability in Higher Education: A Multi-Phase Qualitative Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinchliffe, G.W.; Jolly, A. Graduate identity and employability. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2011, 37, 563–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C. Exploring students’ emotions and emotional regulation of feedback in the context of learningto teach. In Methodological Challenges in Research on Student Learning; Donche, V., De Maeyer, S., Gijbels, D., van den Bergh, H., Eds.; Garant: Antwerpen, Belgium, 2015; p. 107. [Google Scholar]

- Yepes Zuluaga, S.M.; Granada, W.F.M. Engineers’ self-perceived employability by gender and age: Implications for higher education. Cogent Educ. 2023, 10, 2287928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyberaj, J.; Seibel, S.; Schowalter, A.F.; Pötz, L.; Richter-Killenberg, S.; Volmer, J. Developing Sustainable Careers during a Pandemic: The Role of Psychological Capital and Career Adaptability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Mohan, A. Soft Skills For Effective Teaching—Learning: A Review Based Study. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. (IJSRP) 2022, 12, 12530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caringal-Go, J.; Carr, S.; Hodgetts, D.; Intraprasert, D.; Maleka, M.; McWha-Hermann, I.; Meyer, I.; Mohan, K.; Nguyen, M.; Noklang, S.; et al. Work education and educational developments around sustainable livelihoods for sustainable career development and well-being. Aust. J. Career Dev. 2024, 33, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkermans, J.; Le Blanc, P.; Van der Heijden, B.; De Vos, A. Toward a contextualized perspective of employability development. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2023, 33, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Feng, Y.; Jiang, X. How Does Forgone Identity DwellingFoster Perceived Employability: ASelf-Regulatory Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabor, M.R.; Blaga, P.; Matis, C. Supporting Employability by a Skills Assessment Innovative Tool—Sustainable Transnational Insights from Employers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, M.; Gao, T. For Sustainable Career Development: Framework and Assessment of the Employability of Business English Graduates. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 847247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P.R. The Role of Metacognitive Knowledge in Learning, Teaching, and Assessing. Theory Pract. 2002, 41, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorke, M.; Knight, P. Evidence-informed pedagogy and the enhancement of student employability. Teach. High. Educ. 2007, 12, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenjing, L.; Liu, J. Soft skills, hard skills: What matters most? Evidence from job postings. Appl. Energy 2021, 300, 117307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamri, J.; Lubart, T. Reconciling Hard Skills and Soft Skills in a Common Framework: The Generic Skills Component Approach. J. Intell. 2023, 11, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firescu, V. Increasing Collaboration Between Humans and Technology Within Organizations: The Need for Ergonomics and Soft Skills in Engineering Education 5.0. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Horne, C.; Rakedzon, T. Teamwork Made in China: Soft Skill Development with a Side of Friendship in the STEM Classroom. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwita, K.M.; Kinunda, S.; Obwolo, S.; Mwilongo, N.H. Soft skills development in higher education institutions: Students’ perceived role of universities and students’ self-initiatives in bridging the soft skills gap. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 505, ISSN 2147-4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola, A.; Marcionetti, J.; Savickas, M. Psychometric properties of the Career Adapt-Abilities Scale in Italian young people not in education, employment, or training (NEET). Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porfeli, E.J.; Savickas, M.L. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale–USA form: Psychometric properties and relation to vocational identity. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 748–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johari Window of Personality Test Online. Available online: https://kevan.org/johari (accessed on 26 December 2024).

- Koltsova, E.A.; Boyko, S.A. Flipped Classroom Approach in Language Classes for Oil and Gas Engineering Master Students Integration of Engineering Education and the Humanities: Global Intercultural Perspectives. In IEEHGIP 2022; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 449, pp. 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonge, J.d.; Peeters, M.C.W. At Work with Sustainable Well-Being and Sustainable Performance: Testing the DISC Model Among Office Workers. Sustainability 2025, 17, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Lawrence, A.; Xu, X. Does a stick work? A meta-analytic examination of curvilinear relationships between job insecurity and employee workplace behaviors. J. Organ. Behav. 2022, 43, 1410–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langerak, J.B.; Koen, J.; van Hooft, E.A.J. How to minimize job insecurity: The role of proactive and reactive coping over time. J. Vocat. Behav. 2022, 136, 103729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrier, A.; Sels, L. The concept employability: A complex mosaic. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Dev. Manag. 2003, 3, 102–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantassova, D.; Churchill, D.; Tentekbayeva, Z.; Aitbayeva, S. STEM Language Literacy Learning in Engineering Education in Kazakhstan. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varlakova, E.; Bugreeva, E.; Maevskaya, A.; Borisova, Y. Instructional Design of an Integrative Online Business English Course for Master’s Students of a Technical University. Educ.Sci. 2023, 13, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sveshnikova, S.A.; Skornyakova, E.R.; Troitskaya, M.A.; Rogova, I.S. Development of Engineering Studens’ Motivation and Independent Learning Skills. Eur. J. Contemp. Educ. 2022, 11, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Jiang, L.; Chen, L. Get a little help from your perceived employability: Cross-lagged relations between multi-dimensional perceived employability, job insecurity, and work-related well-being. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2022, 31, 880–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Zhang, D.; Jin, Y. Understanding the Push-Pull Factors for Joseonjok (Korean-Chinese) Students Studying in South Korea. Sustainability 2024, 16, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramisetty, J.; Desai, K.; Ramisetty-Mikler, S. Measurement of Employability Skills and Job Readiness Perception of Post-graduate Management students: Results from A Pilot Study. Int. J. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2017, 5, 82–94. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320735657_Measurement_of_Employability_Skills_and_Job_Readiness_Perception_of_Post-graduate_Management_students_Results_from_A_Pilot_Study (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Qi, X.; Chen, Z. A Systematic Review of Technology Integration in Developing L2 Pragmatic Competence. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, T.M.; Grieger, K.; Miller, S.; Nyachwaya, J. Exploring the Nature and Role of Students’ Peer-to-Peer Questions During an In-Class Collaborative Activity. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Students | Professors |

|---|---|

| Grasp of knowledge within and beyond the discipline | Integrating knowledge, skills, and competencies required in various disciplines |

| Employment of carefully selected evidence | A curriculum reflecting the newest international knowledge within the engineering discipline |

| Universal skills being applicable in multiple contexts | Conducting regular reviews of required labor market knowledge, skills, and competencies |

| Advanced strategies for learning | Selecting and employing advanced strategies for teaching |

| Examining individual learning styles, capabilities, and needs | Using cognitive strategies for differentiation in task difficulty |

| Soft Skills | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Skills | Personal Skills | ||

| Effective communication | Empathy | Motivation | Self-regulation |

| Ability to find common ground with everyone, to attract others, to prevent and solve conflicts: interpersonal impact; relationship reinforcement; time administration; team building | Ability to empathize with the emotions of others, experience yourself through another person: accepting different points of view; understanding other people; high level of public awareness | Ability to overcome short-term difficulties in order to achieve a goal: initiative; positivity; commitment to the goal and its implementation | Ability to control emotions and behavior: reliability; conscientiousness; adaptability; creativity |

| Active listening | Conflict resolution | Critical thinking | Self-awareness |

| Readiness for listening; noticing the verbal and nonverbal cues being exchanged; giving accommodating input | Skill in finding solutions agreeable to all involved | Ability to question and test assumptions; adept at spotting ambiguity; explore; interpret in order to evaluate and reflect | Awareness and understanding of emotions, strengths, and weaknesses: emotional awareness; accurate self-assessment; self-confidence |

| Social Skills | CAAS Factors | Personal Skills | CAAS Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effective communication | Confidence | Self-awareness | Confidence |

| Empathy | Concern | Motivation | Concern |

| Active listening | Curiosity | Critical thinking | Curiosity |

| Conflict resolution | Control | Self-regulation | Control |

| Factors | Items |

|---|---|

| Concern | 1. Wondering what my future will be like |

| 2. Knowing that today’s choices determine my future | |

| 3. Preparing for the future | |

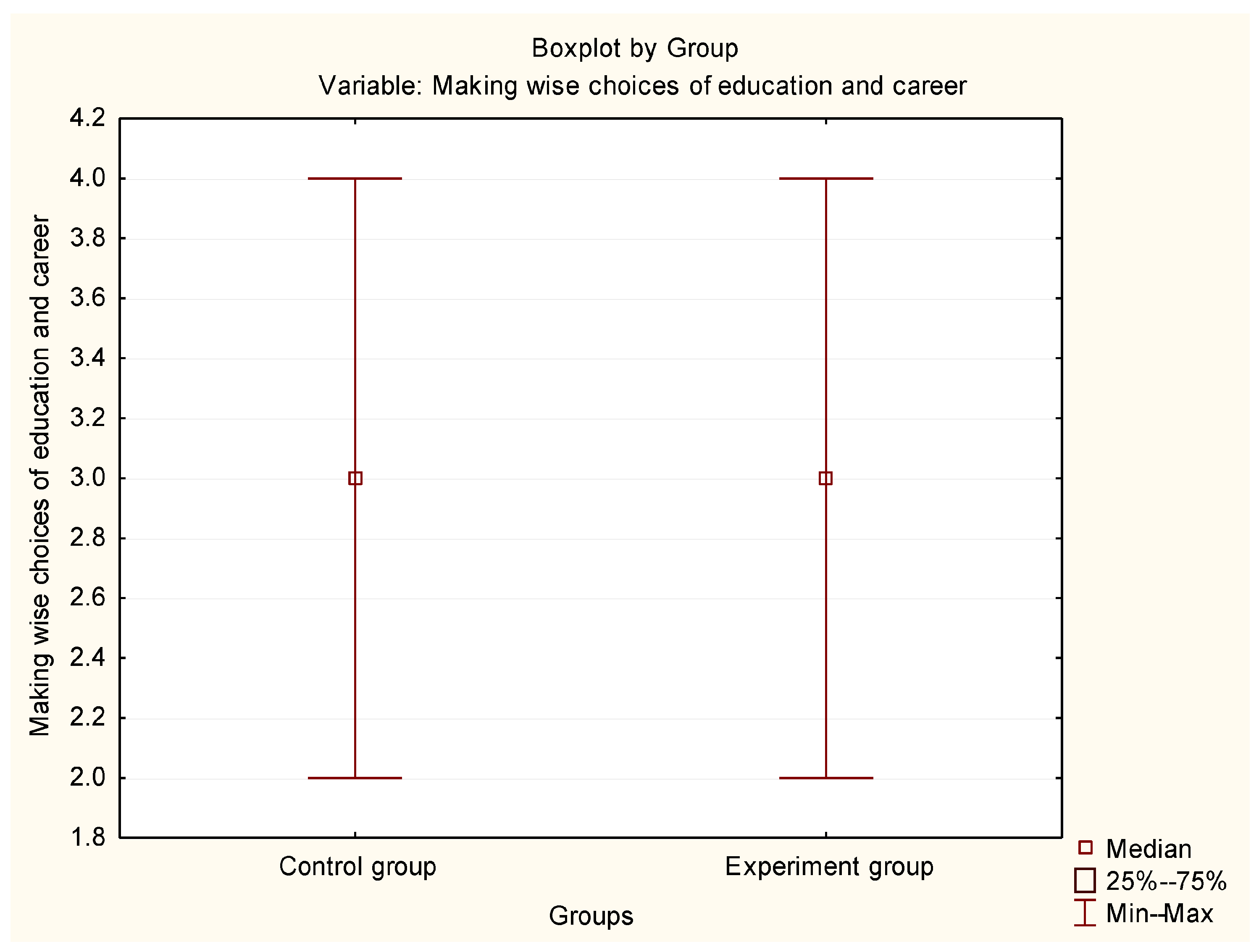

| 4. Making wise choices of education and career | |

| 5. Planning ways of achieving my goals | |

| 6. Concerns about career advancing | |

| Control | 1. Encouraging spirit and feeding mind and body |

| 2. Making decisions independently | |

| 3. Taking responsibility for the actions | |

| 4. Being able to defend my beliefs | |

| 5. Believe in myself | |

| 6. Doing what’s suitable for me | |

| Curiosity | 1. Examining the professional field |

| 2. Looking for possibilities for personal growth | |

| 3. Exploring options before making a choice | |

| 4. Monitoring various ways of doing things | |

| 5. Thinking deeply about the issues I have | |

| 6. Increasing interest in opportunities | |

| Confidence | 1. Finding the most efficient way of performing tasks |

| 2. Being responsible for the choice | |

| 3. Acquisition of new skills | |

| 4. Working within my capabilities | |

| 5. Overcoming obstacles | |

| 6. Troubleshooting skills |

| Arena Known to self and others | Blind spot Unknown to self and known to others |

| Façade Known to self and unknown to others | Unconscious Unknown to self and others |

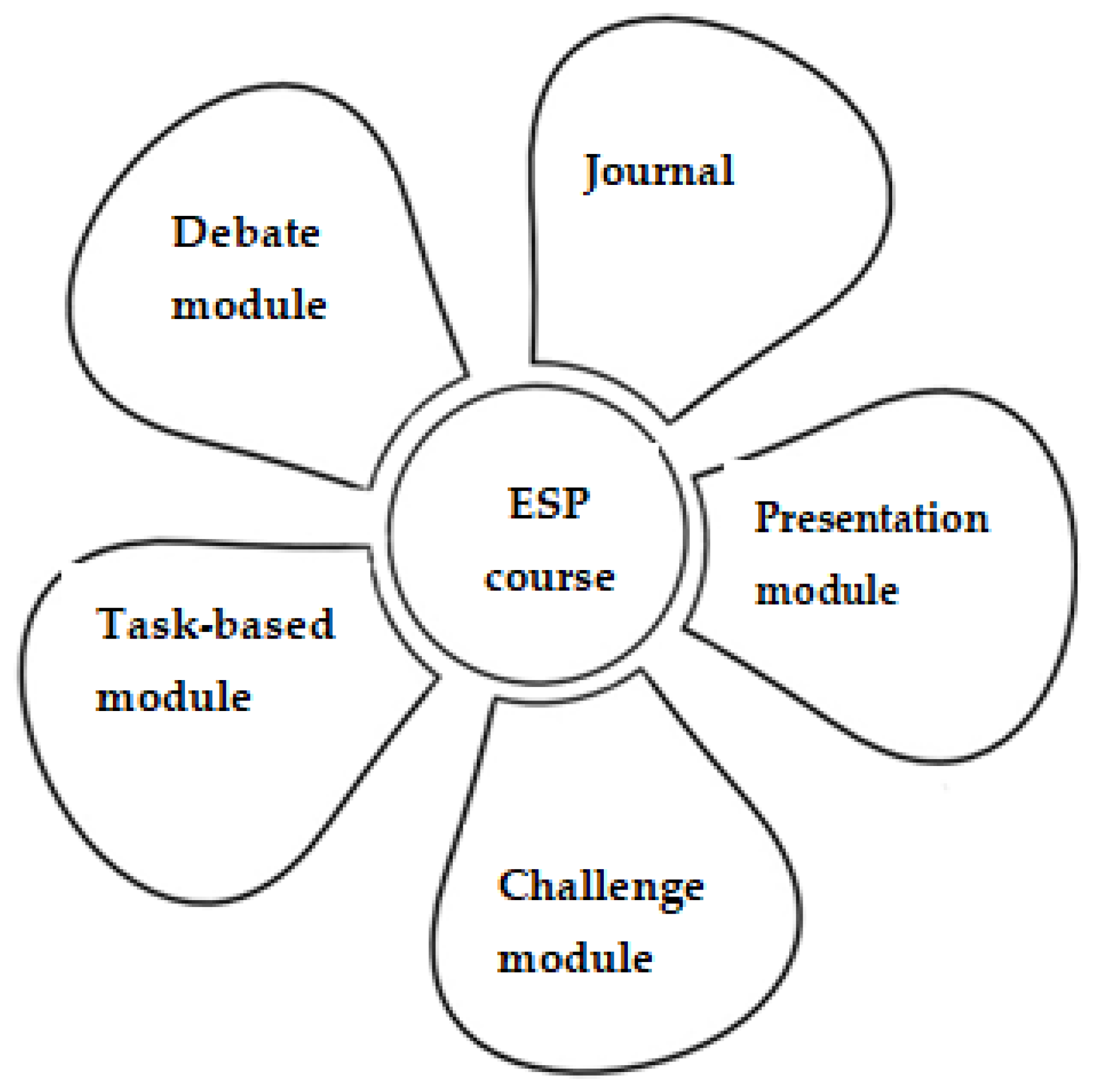

| ESP course | Module | Career adapt-abilities scale factors | Soft skills |

| Debate | Control | conflict resolution, self-regulation | |

| Presentation | Confidence | communication | |

| Task-based (teamwork) | Concern | empathy, motivation | |

| Challenge | control, concern | self-regulation, motivation | |

| Journal | Curiosity | critical thinking |

| Module | Features |

|---|---|

| Debate |

|

| Presentation |

|

| Task-based (teamwork) |

|

| Challenge |

|

| Journal |

|

| № | Module/Topic | Content | Hours |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Stages of presentation preparation | four steps to a successful start; explaining the main points and using examples; how to end the presentation and lead the discussion | 9 |

| 2 | Writing a speech in English | how to put complex things into simple words; using synonyms; using correct and standardized terms | 9 |

| 3 | Pronunciation and intonation | ‘false friends”; pronunciation of numerals and fractions; the importance of a correct accent | 9 |

| 4 | Examples of successful presentations | what makes a presentation successful; TED format; analyses of successful presentations | 9 |

| 5 | Psychological aspects | awareness of fears; positive attitude; breathing techniques | 9 |

| 6 | Preparation of visuals | title and title slide; use of verbs and prepositions; grammar and spelling; layout | 9 |

| 7 | Giving a paper | how to start a speech; engaging the audience; use of examples | 9 |

| 8 | Practical application of the studied material | speech preparation; presentation preparation; giving a presentation | 9 |

| Total | 72 | ||

| Groups | Variables | Wondering What My Future Will Be Like | Knowing That Today’s Choices Determine My Future | Preparing for the Future | Making Wise Choices of Education and Career | Planning Ways of Succeeding My Goals | Concerns About Career Advancing | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | ||

| Control group | Mean | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.13 | 2.50 |

| ±SD | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.85 | 0.81 | |

| Median | 3.0 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | |

| Q1 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | |

| Q3 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | |

| MannWhitney Z test | 4.82 | 4.82 | - | 6.22 | - | 4.49 | |||||||

| P (before-after) | 0.000 | 0.000 | - | 0.000 | - | 0.000 | |||||||

| Difference between groups, % | −16.7% | 20.0% | 0.0% | −33.3% | 0.0% | 17.4% | |||||||

| Experimental group | Median | 3.0 | 4.0 | 2.5 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 4.5 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 |

| Q1 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | |

| Q3 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | |

| MannWhitney Z test | 8.44 | 8.68 | 8.64 | 8.68 | 8.64 | 7.11 | |||||||

| p value (before-after) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||

| Difference between groups, % | 33.3% | 40.0% | 50.0% | 33.3% | 50.0% | 33.3% | |||||||

| Difference between groups | MannWhitney Z-test | 0.15 | −10.5 | 0.00 | −2.93 | 0.00 | −8.66 | 0.00 | −11.7 | −0.10 | −7.59 | −8.49 | −8.87 |

| p value | 0.879 | 0.000 | 0.999 | 0.003 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.924 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Difference between groups, % | 0.0% | 60.0% | 0.0% | 16.7% | 0.0% | 50.0% | 0.0% | 100% | 0.0% | 50.0% | 50.0% | 100% | |

| Groups | Variables | Encouraging Spirit and Feeding Mind and Body | Making Decisions Independently | Taking Responsibility for the Actions | Being Able to Defend My Beliefs | Believe in Myself | Doing What’s Suitable for Me | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | ||

| Control group | Mean | - | - | 2.00 | 2.05 | 2.11 | 2.18 | 1.79 | 1.98 | 1.57 | 1.98 | 1.70 | 2.00 |

| ±SD | - | - | 0.72 | 0.69 | 0.80 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0.45 | |

| Median | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | |

| Q1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | |

| Q3 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | |

| MannWhitney Z test | 0.53 | 2.02 | 2.37 | 3.72 | 4.91 | 4.29 | |||||||

| P (before-after) | 0.593 | 0.043 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||

| Difference between groups, % | 0.0% | 2.5% | 3.3% | 10.6% | 26.1% | 17.6% | |||||||

| Experimental group | Average | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.03 | - | - | - | - | - |

| ±SD | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.85 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Median | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | |

| Q1 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | |

| Q3 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 3.3 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | |

| MannWhitney Z test | 8.68 | 7.72 | 8.68 | 8.68 | 8.64 | 8.33 | |||||||

| P (before-after) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||

| Difference between groups, % | 50.0% | 50.0% | 50.0% | 50.0% | 50.0% | 50.0% | |||||||

| Difference between groups | MannWhitney Z-test | 0.09 | −6.85 | −0.84 | −6.84 | 0.00 | −8.80 | −1.88 | −8.62 | 0.00 | −10.46 | −0.41 | −7.46 |

| p value | 0.925 | 0.000 | 0.399 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.060 | 0.000 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.682 | 0.000 | |

| Difference between groups, % | 0.0% | 50.0% | 0.0% | 50.0% | 0.0% | 50.0% | 13.4% | 50.0% | 0.0% | 50.0% | 0.0% | 50.0% | |

| Groups | Variables | Examining the Professional Field | Looking for Possibilities for Personal Growth | Exploring Options Before Making a Choice | Monitoring Various Ways of Doing Things | Thinking Deeply About the Issues I Have | Increasing Interest in Opportunities | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | ||

| Control group | Mean | 2.20 | 2.48 | - | - | 1.80 | 2.42 | 1.69 | 2.17 | 1.63 | 2.07 | 2.23 | 2.38 |

| ±SD | 0.93 | 0.69 | - | - | 0.88 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.43 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.63 | 0.51 | |

| Median | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | |

| Q1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | |

| Q3 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | |

| MannWhitney Z test | 3.70 | - | 5.91 | 5.30 | 5.08 | 2.80 | |||||||

| P (before-after) | 0.000 | - | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.005 | |||||||

| Difference (before-after), % | 12.7% | 0.0% | 34.4% | 28.4% | 27.0% | 6.7% | |||||||

| Experimental group | Average | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.22 | - | - | - |

| ±SD | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.63 | - | - | - | |

| Median | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | |

| Q1 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 2.8 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | |

| Q3 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | |

| MannWhitney Z test | 8.68 | 8.68 | 8.64 | 8.51 | 8.55 | 8.68 | |||||||

| P (before-after) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||

| Difference (before-after), % | 33.3% | 66.7% | 100.0% | 50.0% | 100.0% | 50.0% | |||||||

| Difference between groups | MannWhitney Z-test | −4.18 | −9.48 | 0.00 | −12.06 | 0.32 | −11.63 | 0.00 | −7.11 | −5.49 | −12.11 | 0.15 | −8.95 |

| p value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.748 | 0.000 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.883 | 0.000 | |

| Difference between groups, % | 50.0% | 100% | 0.0% | 66.7% | 0.0% | 100% | 0.0% | 50.0% | 36.2% | 100% | 0.0% | 50.0% | |

| Groups | Variables | Finding the Most Efficient Way of Performing Tasks | Being Responsible for the Choice | Acquisition of New Skills | Working Within My Capabilities | Overcoming Obstacles | Troubleshooting Skills | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | ||

| Control group | Mean | 1.56 | 2.08 | - | - | 1.93 | 2.16 | 2.64 | 2.78 | 1.76 | 2.21 | - | - |

| ±SD | 0.57 | 0.31 | - | - | 0.64 | 0.37 | 0.98 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.41 | - | - | |

| Median | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 | |

| Q1 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | |

| Q3 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | |

| MannWhitney Z test | 6.15 | 7.47 | 4.02 | 3.30 | 5.84 | 5.99 | |||||||

| P (before-after) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||

| Difference (before-after), % | 33.3% | 150.0% | 11.9% | 5.3% | 25.6% | 33.3% | |||||||

| Experimental group | Average | 1.90 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ±SD | 0.61 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Median | 2.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 5.0 | |

| Q1 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | |

| Q3 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 5.0 | |

| MannWhitney Z test | 8.68 | 8.68 | - | 8.68 | 8.59 | 8.51 | |||||||

| P (before-after) | 0.000 | 0.000 | - | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||

| Difference (before-after), % | 50.0% | 200.0% | - | 50.0% | 33.3% | 33.3% | |||||||

| Difference between groups | MannWhitney Z test | −3.45 | −8.51 | 0.00 | −1.07 | 0.28 | −9.15 | 0.00 | −8.48 | −6.01 | −11.07 | −1.86 | −12.14 |

| p value | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.999 | 0.286 | 0.782 | 0.000 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.062 | 0.000 | |

| Difference between groups, % | 21.8% | 50.0% | 0.0% | 20.0% | 0.0% | 50.0% | 0.0% | 33.3% | 50.0% | 100% | 33.3% | 150% | |

| Groups | Variables | Open Area | Blind Area | Hidden Area | Unknown Area | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | Before ESP Training | After ESP Training | ||

| Control group | Mean | - | - | 2.06 | 1.91 | 3.93 | 3.79 | - | - |

| ±SD | - | - | 0.57 | 0.65 | 0.61 | 0.71 | - | - | |

| Median | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 47.0 | 48.0 | |

| Q1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 47.0 | 47.0 | |

| Q3 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 48.0 | 49.0 | |

| MannWhitney Z test | 2.73 | 1.87 | 2.93 | 4.36 | |||||

| P (before-after) | 0.006 | 0.062 | 0.003 | 0.000 | |||||

| Difference (before-after), % | −33.3% | −7.3% | −3.6% | 2.1% | |||||

| Experimental group | Average | - | - | 2.32 | - | - | - | 47.08 | - |

| ±SD | - | - | 0.68 | - | - | - | 1.02 | - | |

| Median | 3.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 47.0 | 46.0 | |

| Q1 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 46.0 | 46.0 | |

| Q3 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 48.0 | 47.0 | |

| MannWhitney Z test | 8.10 | 6.97 | 8.23 | 5.24 | |||||

| P (before-after) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||

| Difference (before-after), % | 33.3% | 50.0% | −50.0% | −2.1% | |||||

| Difference between groups | MannWhitney Z test | 0.04 | −10.89 | −2.75 | −8.91 | 0.00 | 10.28 | 2.02 | 6.91 |

| p value | 0.970 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.043 | 0.000 | |

| Difference between groups, % | 0.0% | 100.0% | 12.6% | 50.0% | 0.0% | −50.0% | −0.5% | −4.2% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gerasimova, I.; Oblova, I. Sustainable Development of Soft Skills with the Purpose of Enhancing the Employability of Engineering Students. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2426. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062426

Gerasimova I, Oblova I. Sustainable Development of Soft Skills with the Purpose of Enhancing the Employability of Engineering Students. Sustainability. 2025; 17(6):2426. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062426

Chicago/Turabian StyleGerasimova, Irina, and Irina Oblova. 2025. "Sustainable Development of Soft Skills with the Purpose of Enhancing the Employability of Engineering Students" Sustainability 17, no. 6: 2426. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062426

APA StyleGerasimova, I., & Oblova, I. (2025). Sustainable Development of Soft Skills with the Purpose of Enhancing the Employability of Engineering Students. Sustainability, 17(6), 2426. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062426