Abstract

Air pollution is a critical global issue affecting sustainable development, and effectively addressing air pollution requires consumers to improve air quality through daily pro-environmental behaviors. This study aims to explore the influence mechanisms of multidimensional risk perception variables on consumers’ pro-environmental behaviors. It introduces risk effect, risk controllability, risk trust, and risk acceptability and incorporates multidimensional risk perception variables into the theory of planned behavior (TPB) model. The results of the structural equation model indicate that risk effect, risk trust, and risk acceptability of air pollution significantly influence pro-environmental behaviors through behavioral intentions. Moreover, the risk effect, risk trust, and risk acceptability of air pollution significantly influence consumers’ pro-environmental behaviors through the chain-mediating effect of attitudes and behavioral intentions. The risk controllability does not affect consumers’ behavioral intentions or pro-environmental behaviors. Through the integration of multidimensional risk perception and the validation of the behavioral intention–behavior gap, this study provides new perspectives for research related to consumer pro-environmental behavior. It also provides references for the government to communicate with consumers about risks, solve air pollution problems, and achieve sustainable development.

1. Introduction

Air pollution is one of the most prominent concerns affecting the public’s daily life [1]. According to a World Health Organization (WHO) report, air pollution is one of the greatest environmental risks to health [2]. Previous research has demonstrated a strong association between air pollution and various diseases, including respiratory diseases [3], cardiovascular diseases [4], cancers [5], and psychiatric diseases [6]. In addition, air pollution not only damages agriculture [7] and forestry and poses a significant threat to the sustainability of forest ecosystems [8] but also affects the sustainable development of local tourism and hinders economic development [9]. All the aforementioned points suggest that air pollution poses a significant threat to sustainable development, making it imperative to improve air quality.

The Chinese government has implemented several strategies to address air pollution. For example, the “Three-year Plan on Defending the Blue Sky” was issued by the State Council of China [10]. While these efforts have improved air quality, the situation remains unsatisfactory. Heavily polluted weather during the fall and winter continues to affect the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region and its surrounding areas, with more than half of China’s cities still experiencing severe pollution [11]. Traditional top–down planning is insufficient for fully resolving air pollution issues. A diversified governance approach incorporating bottom–up initiatives is needed to address the air pollution problem [12]. The diversified governance approach emphasizes the involvement of non-state actors; enterprises, the government, and the public need to collaborate to control air pollution [13]. Thus, as a member of the public, it is imperative that consumers be encouraged to adopt pro-environmental behaviors to enhance air quality. Pro-environmental behaviors are sustainable practices by consumers for achieving environmental sustainability, such as purchasing green products and conserving energy.

Despite the importance of such behaviors, many shortcomings remain in fostering a strong public sense of pro-environmental behavior in China [14]. An insufficient understanding of pro-environmental behaviors influences the appropriate implementation of regulations to control air pollution and the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) [14,15]. Therefore, identifying the factors that affect consumers’ pro-environmental behaviors is crucial. The theory of planned behavior (TPB) as a psychological model is widely used in pro-environmental behavior research. It is often applied to study individuals’ decision-making processes regarding pro-environmental and sustainable behaviors, e.g., energy conservation and reducing private road transportation [16,17]. However, there are concerns regarding the validity of the TPB model since it is unable to adequately describe and forecast individual actions on its own [18,19]. Additional psychological factors have been integrated into the TPB model to optimize it and to enhance its explanatory power [20,21].

Risk perception, as a psychological factor that explains the motivation of individual behaviors, has been widely accepted and applied [22,23]. Risk perception has been incorporated into the TPB model to increase its explanatory power. Rezaei et al. [24] integrated a single dimension of risk perception into the TPB to examine Iranian farmers’ intentions to utilize fertilizers safely, resulting in an 11.2% increase in the explanatory power of the model. However, they failed to differentiate the multidimensional attributes of risk perception and were thus unable to uncover the heterogeneous effects of different risk perception dimensions on behavior. The impacts of multidimensional risk perception on pro-environmental behavior are rarely examined in the current literature, despite the fact that risk perception is multidimensional and that examining the relationship between risk perception and pro-environmental behavior from a multidimensional risk perception perspective will be more thorough and in-depth. In addition, most studies based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB) focus only on the prediction of behavioral intention and lack empirical testing of the relationship between behavioral intention and actual behavior (pro-environmental behavior) [25].

To address these research gaps, this study aims to explore the mechanisms of how multidimensional risk perception variables influence consumers’ pro-environmental behaviors and the relationship between behavioral intention and pro-environmental behavior. Another objective is to examine the applicability of the extended TPB model to the study of pro-environmental behavior. To achieve the above objectives, this study introduces four dimensions of risk perception, namely risk effect, risk controllability, risk trust, and risk acceptability. This study subsequently incorporates multidimensional risk perception variables into the TPB model, extending the model to explore the link between consumers’ risk perception regarding air pollution and pro-environmental behavior. A structural equation model (SEM) is applied to analyze the data.

This study offers a dual contribution. First, compared with Rezaei et al.’s [24] unidimensional risk integration, this study constructs a new theoretical framework containing four dimensions of risk perception (risk effect, risk controllability, risk trust, and risk acceptability) and validates the different effects of multidimensional risk perception on consumers’ pro-environmental behavior through structural equation modeling, expanding the application of the TPB in pro-environmental behavior research. In addition, it confirms the existence of a gap between behavioral intention and pro-environmental behavior and that behavioral intention can be converted into pro-environmental behavior to a certain extent. Second, it provides valuable insights to the government for raising consumers’ awareness of environmental protection and enhancing consumers’ pro-environmental behaviors to improve air quality and to achieve the goal of sustainable development from the perspective of consumers’ risk perception of air pollution.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the relevant theoretical foundations and presents the hypotheses based on the existing literature. Section 3 details the research methodology. Section 4 presents the empirical results. Section 5 discusses the theoretical and policy implications of the findings. Section 5 also compares the results with previous studies. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the study, highlights its limitations, and suggests directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

Until recently, the TPB has been the most commonly used theory and model in the study of behavioral intentions and behaviors. The TPB posits that behavioral intention is the most proximate determinant of behaviors [26]. Behavioral intention is influenced by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control [26]. The TPB is a valuable tool for predicting behavioral intentions and pro-environmental behaviors. For example, Ajzen et al. [27] applied the theory of planned behavior to explore the factors individuals consider when they intend to and actually engage in leisure activities, as well as the ability of these factors to predict leisure intentions and behaviors. However, the traditional theory of planned behavior (TPB) demonstrates limited explanatory power regarding behavioral variance [28] and lacks the integration of external variables such as risk perception [24].

2.2. Attitude

Attitude represents the individual’s evaluation of a specific behavioral performance, which can be positive or negative [27]. Attitude tends to be positive when the expected effect of the action is favorable [29]. Since attitude, once formed, is difficult to change, it is a significant predictor of behavioral intention [30]. Many studies have shown that attitude is one of the factors that can predict behaviors. For instance, Savari and Gharechaee [31] reported that farmers’ attitude toward fertilizers has a positive and significant influence on their willingness to use fertilizers safely.

Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1.

Attitude positively affects consumers’ behavioral intention.

2.3. Subjective Norms

Subjective norms emphasize how individuals feel social pressure from family, friends, and peers within their social context [32]. Prior research has shown that individuals’ behaviors often stem from their perceptions of others’ expectations, and those close to them influence their behavioral intentions [33].

Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2.

Subjective norms positively affect consumers’ behavioral intention.

2.4. Perceived Behavioral Control

Perceived behavioral control is a presumption and judgment made by an individual about his or her ability to perform a certain behavior, and this ability could involve time, money, skills, opportunities, and resources [25]. Although some abilities are beyond individual control, they can still influence the individual’s behavioral intention. Individuals who perceive themselves as more capable are more likely to perform specific behaviors. For instance, if companies possess sufficient knowledge and skills for green transformation, their managers are more likely to pursue it [34].

Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3.

Perceived behavioral control positively affects consumers’ behavioral intention.

2.5. Attitudes, Subjective Norms, Perceived Behavioral Control, and Pro-Environmental Behavior

Furthermore, this research attempts to test the mediating effects between different characteristics of consumers’ behaviors. Prior studies have indicated that attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control are strongly correlated and interact with each other [35,36]. Rekola [36] demonstrated that subjective norms can influence pro-environmental behaviors before attitudes and perceived behavioral control. In addition, this finding was also supported by Nair and Little [37].

Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4.

Subjective norms indirectly influence consumers’ behavioral intention through attitudes.

H5.

Subjective norms indirectly influence consumers’ behavioral intention through perceived behavioral control.

2.6. Consumers’ Behavioral Intention and Pro-Environmental Behavior

Behavioral intention indicates the degree of an individual’s willingness to attempt and complete a program, and it is the closest factor to behavior. Strong intentions ultimately lead to behaviors [38], but research exploring the link between behavioral intention and pro-environmental behavior is limited. This research explores the link between consumers’ behavioral intention and pro-environmental behavior.

Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H6.

Consumers’ behavioral intention positively affects their pro-environmental behavior.

2.7. Air-Quality Risk Perception and the TPB

It has been demonstrated that the traditional TPB model predicts and explains a limited amount of variance, and it is necessary to add more variables to extend the model to enhance its predictive and explanatory powers [28]. Researchers have emphasized that the TPB model lacks the risk perception concept [39]. Risk perception has been studied from different perspectives and combined with the TPB model to extend the latter [40]. Risk perception significantly influences individuals’ attitude and behavioral intention [41,42]. Citing Slovic’s [43] classic framework on the multidimensionality of risk perception, this study incorporates multidimensional risk perception variables, specifically risk effect, risk controllability, risk trust, and risk acceptability, for air pollution. Risk effect reflects individual perceptions of the health and economic consequences of air pollution [44]. J. Yang et al. [45] found that the impact level of air pollution significantly affected respondents’ willingness to pay. Risk controllability is based on Fischhoff’s [46] theory of risk controllability. It reflects consumers’ degree of control over perceived risky events, the predictability of risky events, and the degree of control over avoiding risk hazards [47]. Slovic et al. [43] noted that high controllability may diminish an individual’s urgency to take action. Eser et al.’s research found that risk controllability has a significant impact on the willingness to buy insurance [48]. For the concept of risk trust, this study cites the research of Pu et al. [49], which argues that government trust is a key driver of public participation in environmental governance. Risk trust reflects the level of consumers’ trust in the ability of the government to control air pollution [49]. Nguyen et al. [50] revealed that the greater the consumers’ level of trust in the government is, the greater the likelihood that consumers will take action in the face of air pollution. Risk acceptability is based on Fischhoff and Slovic’s [46] tolerance model, which explains how an individual’s threshold of tolerance for the negative effects of pollution affects their motivation to engage in relevant behaviors. Risk acceptability reflects consumers’ ability to tolerate damage caused by air pollution [46]. Fischhoff et al. [46] suggest that a high level of risk acceptance may lead individuals to ignore the severity of environmental problems. Mao et al. [44] found that individuals with a higher level of risk acceptability were more averse to contributing to the improvement of air quality.

Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H7.

Risk effect positively affects consumers’ behavioral intention.

H8.

Risk controllability negatively affects consumers’ behavioral intention.

H9.

Risk trust positively affects consumers’ behavioral intention.

H10.

Risk acceptability negatively affects consumers’ behavioral intention.

H11.

Risk effect (a), risk controllability (b), risk trust (c), and risk acceptability (d) indirectly affect consumers’ behavioral intention through attitude.

H12.

Risk effect (a), risk controllability (b), risk trust (c), and risk acceptability (d) indirectly affect consumers’ pro-environmental behavior through behavioral intention

H13.

Risk effect (a), risk controllability (b), risk trust (c), and risk acceptability (d) indirectly affect consumers’ pro-environmental behavior through the chain-mediating effect of attitude and behavioral intention.

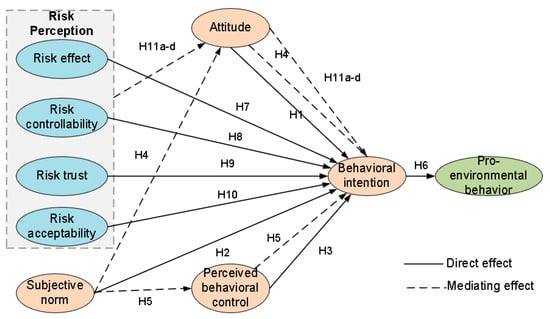

Therefore, this research integrates multidimensional risk perception variables into the TPB model and, consequently, proposes a conceptual model, as shown in Figure 1. It is an extended TPB model that incorporates multidimensional risk perception variables as antecedent variables to explore how the multidimensional risk perception of air pollution affects consumers’ pro-environmental behavior.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

Harbin is the capital city of Heilongjiang Province, located in Northeast China. Harbin’s tourism industry is a significant pillar of Harbin’s economic development. A tourist city’s environment significantly influences the tourism industry’s sustainability. However, Harbin’s air quality is ranked relatively low among China’s 168 key cities [51]. Simultaneously, industrial development has intensified air pollution in Harbin. The frequent occurrence of hazy weather affects both residents’ lives and sense of well-being, as well as tourists’ experience and travel satisfaction. Therefore, Harbin should urgently take effective measures to control air pollution. Hence, Harbin was selected as the study area, and the survey design was based on this area.

3.2. Questionnaire Design

The questionnaire was designed based on a comprehensive literature review. There are four parts to the questionnaire. Part 1 comprises a scale of the multidimensional risk perception variables related to air pollution among consumers, and it is derived from previous research [44,46,47,49]. The second part measures consumers’ attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. The third part consists of a scale with four items that measure consumers’ pro-environmental behavior. The specifics of Parts 1 to 3 are shown in Table A1. A five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) was used to measure the items from Part 1 to Part 3. Of the five choices, the respondents were required to select the one with which they agreed. The fourth part covers the demographic characteristics of the respondents, including gender, age, education level, the number of children, and the number of cars in the household.

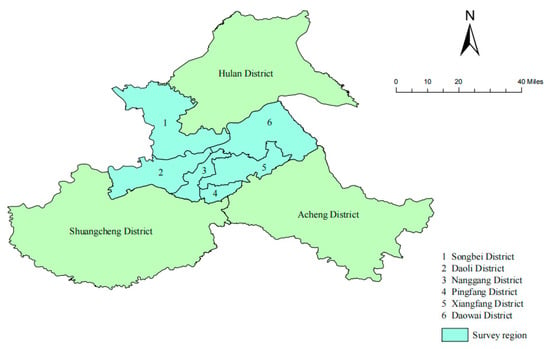

3.3. Sample Selection and Data Collection

Harbin has nine urban districts under its jurisdiction, six of which are in the inner city, including Songbei District, Daoli District, Nangang District, Pingfang District, Xiangfang District, and Daowai District. The district map of Harbin is shown in Figure 2. The six districts encompass the majority of the population, so this study takes the six districts as the research area. The sample size is allocated according to the population proportion of each district. Population proportions, sample allocations, and recall data for each district are shown in Table A2.

Figure 2.

Harbin city district map.

The sample size for this study was calculated based on Cochran’s formula. The formula is as follows:

In the formula, = 1.96 (corresponding to a 95% confidence level), = 0.5 (maximum variance assumption), and the margin of error = 5%. The theoretical minimum sample size was calculated as = 384. Considering the design effect of stratified sampling (the design effect coefficient was set to 1.2), the adjusted target sample size was 461.

Before the formal investigation, a pilot survey was carried out with 50 randomly selected respondents in order to revise any unclear or misleading content in the questionnaire. The formal investigation was conducted in October 2019 via stratified random sampling. Moreover, both the pilot survey and the formal investigation used face-to-face interviews. To minimize sampling bias, the survey time covered weekdays and weekends, and public places (e.g., parks, shopping malls) were selected for data collection. During the interview process, to reduce non-sampling errors caused by human factors as much as possible, our interviewers randomly selected the respondents they encountered. Then, they introduced the purpose of our study to them and invited them to fill out the questionnaire, giving them a gift as compensation. Questionnaires were considered invalid when the same option was selected for all questions or when the logic was inconsistent. Ultimately, 43 out of 492 questionnaires were excluded, leaving 449 valid questionnaires, which was close to the target value and met the statistical requirements.

3.4. Data Analysis Methods

3.4.1. Methods of the Reliability and Validity Tests

The reliability of the questionnaire data was examined via Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficients and standardized factor loadings. When α ≥ 0.7 [52] and the standardized factor loadings > 0.6 [53], these conditions indicate that the reliability is desirable.

After assessing reliability, the validity of the questionnaire was also examined. Validity is the degree to which a measurement tool accurately measures the content to be tested. In this study, we examined the data’s convergent validity and discriminant validity by conducting a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The standardized factor loadings, as well as combined reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) values in Table 1 are based on the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results. Convergent validity reflects the extent to which different measures of the same construct yield similar results. Discriminant validity reflects the difference between latent constructs. Based on established guidelines, when the standardized factor loadings are greater than 0.6, the composite reliability (CR) values are greater than 0.7, and the average variance extracted (AVE) values are greater than 0.5, it suggests that the convergent validity of the model is favorable [54,55]. Similarly, for discriminant validity, when the square root of the AVE value of the latent variable is greater than the correlation between the latent variables, this indicates that the data have satisfactory discriminant validity [56].

Table 1.

Reliability and validity tests.

3.4.2. Structural Equation Modeling

Structural equation modeling uses measurement theory, factor analysis, regression, and path analysis to address theoretical models [57]. It can estimate the statistical significance and magnitude of the structural relationship between theoretical constructs [58]. Risk perception, attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, behavioral intention, and pro-environmental behavior are latent variables that cannot be directly observed or measured. Structural equation modeling allows the impacts of the latent variables to be assessed. Therefore, an SEM is used to explore the relationships among risk perception, attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, behavioral intention, and pro-environmental behavior. In this study, an SEM is utilized to examine the model fitness and the direct and mediating effects between latent variables. Model fitness assesses the effect of model fitting, and the model can explain the actual problem only if it fits the data well.

To test the significance of the mediating effect, this study employed the bias-corrected bootstrap method [59] to generate 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (BCCIs) with 5000 sampling replicates using the AMOS 24.0 software. If the confidence intervals do not contain zero values, this indicates a significant mediation effect. In this study, we assessed the variance accounted for (VAF), which is used to test the types of mediating effects. A VAF value greater than 80% indicates full mediation. The VAF value ranging from 20% to 80% indicates partial mediation. There is no mediation when the VAF value is less than 20%. To measure the explanatory power of the model, this study calculated the value of R2. R2 is the percentage of the variance of the dependent variable that can be explained by the independent variables. The value of R2 ranges from 0 to 1. An R2 value of 0.12 or below indicates weak explanatory power, an R2 value between 0.13 and 0.25 indicates medium explanatory power, and an R2 value of 0.26 or above indicates strong explanatory power [60].

3.5. Descriptive Statistics

The respondents’ demographic characteristics in this study are shown in Table 2. To assess the representativeness of the sample, this study contrasted the demographic data of the respondents with the latest official statistics of Harbin City. The results show that in the sample, the percentage of females (58.1% vs. 50.8%), the 18–40-year age group (87.1% vs. 42.5%), and the those highly educated (87.3% vs. 25.3% with a bachelor’s degree and above) was higher than the citywide average. This bias may be related to the stratified sampling method used in the study (covering the core areas of the city), the selection of survey areas with high pedestrian flow (e.g., parks, shopping malls, and other central areas), and the willingness of the respondents to participate (males and the elderly were more reluctant to take the questionnaire, and the highly educated group was more concerned about environmental issues). In addition to the above-mentioned aspects related to sample representativeness, other demographic characteristics of the respondents are also worth noting. A total of 54.1% of the respondents had no children, and only 25.4% had no cars in their family.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents.

4. Results

4.1. Reliability Test

Table 1 shows that Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficients for all the constructs are greater than 0.7, indicating high internal consistency across the dimensions of the questionnaire. The standardized factor loadings for all question items exceed 0.6, which indicates that the measurement items effectively reflect the latent variables. The results mentioned above indicate that the reliability of the questionnaire is satisfactory. The means in Table 1 reflect the overall tendency of the respondents toward a particular issue. The closer the mean value is to 5, the higher the level of agreement among respondents with the corresponding statement. For example, the mean value of risk effect (RE1) is 3.94. Since the scale ranges from 1–5 (a typical Likert-type scale), this value indicates that respondents generally agree that “air pollution has an effect on the appreciation of the landscape”. The SD (standard deviation) measures the degree of dispersion of the data, with larger values indicating a greater variance in respondents’ answers and more diverse opinions, while smaller values indicate a concentration of responses and a high degree of consistency. For example, the SD of the risk effect (RE3) is 0.946, which indicates that there is a certain degree of divergence in the respondents’ views on the statement that “air pollution has an effect on psychological mood”.

4.2. Validity Test

As shown in Table 1, the standardized factor loadings are greater than 0.6, the composite reliability (CR) values are greater than 0.7, and the average variance extracted (AVE) values are greater than 0.5, suggesting that the convergent validity of the model is favorable [54,55]. Although the AVE value (0.521) of the risk effect is close to the threshold of 0.5, its CR (0.765) and factor loadings (RE1 = 0.747, RE2 = 0.730, RE3 = 0.686; all > 0.6) are in line with the requirements. Additionally, with respect to discriminant validity, as Table 3 shows, the diagonal entries of the table are the square roots of the AVE values of the latent variables. These values are greater than the correlations among the latent variables, indicating that the data have satisfactory discriminant validity [56]. The discriminant validity was verified by comparing the square root of the risk effect’s AVE with its correlation coefficients for other relevant latent variables. Similar situations have been considered acceptable in behavioral research [53].

Table 3.

Correlations between latent variables.

4.3. Model Fitness Test

The results of the model fitness examination are shown in Table A3: CMIN/df = 1.519; RMSEA = 0.034; AGFI = 0.910; GFI = 0.928; SRMR = 0.047; TLI = 0.971; PGFI = 0.745. All of these metrics meet the goodness-of-fit criteria, suggesting favorable fitness of the model.

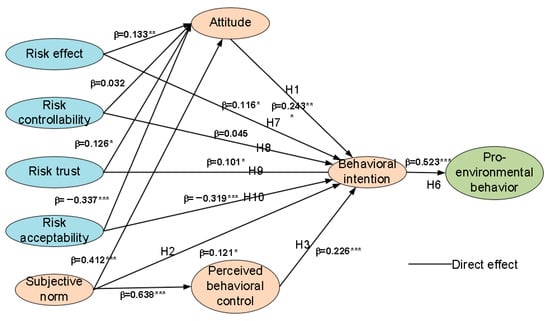

4.4. Hypothesis Testing for Direct Effects

The direct-effect results are shown in Table A4 and Figure 3. The results show that consumers’ attitudes (β = 0.243; p < 0.001) (H1), subjective norms (β = 0.121; p < 0.05) (H2), and perceived behavioral control (β = 0.226; p < 0.001) (H3) significantly and positively affect their behavioral intentions. Consumers’ behavioral intentions significantly and positively affect their pro-environmental behaviors (β = 0.523; p < 0.001) (H6). Moreover, risk effect (β = 0.116; p < 0.05) (H7) and risk trust (β = 0.101; p < 0.05) (H9) significantly and positively affect consumers’ behavioral intentions. Risk acceptability significantly negatively affects consumers’ behavioral intentions (β = −0.319; p < 0.001) (H10). Nevertheless, risk controllability does not affect consumers’ behavioral intentions (β = 0.045; p > 0.05) (H8). Hence, the multidimensional risk perception variables of air pollution significantly affect behavioral intentions.

Figure 3.

Standardized output of direct effects. Note: * significant at the 5% level; ** significant at the 1% level; *** significant at the 0.1% level.

4.5. Hypothesis Testing for Mediating Effects

The results of mediating effects are shown in Table 4. The indirect effects of subjective norms on behavioral intention through attitude (β = 0.087; p < 0.001) (H4) and perceived behavioral control (β = 0.126; p < 0.001) (H5) are all significantly and partially mediated. The results show that only the indirect effect of risk controllability (β = 0.008; p > 0.05) (H11b) on behavioral intention through attitude is insignificant. Attitude plays a significant mediating role in the effects of risk effect (β = 0.035; p < 0.01) (H11a), risk trust (β = 0.031; p < 0.01) (H11c), and risk acceptability (β = -0.075; p < 0.001) (H11d) on behavioral intention. These mediating effects all have variance accounted for (VAF) values that are between 20% and 80%, indicating that they are partially mediated.

Table 4.

Structural model path coefficients and hypothesis testing (mediating effects).

In addition, risk effect (β = 0.068; p < 0.01) (H12a), risk trust (β = 0.055; p < 0.05) (H12c), and risk acceptability (β = −0.159; p < 0.001) (H12d) all significantly and indirectly affect pro-environmental behavior through behavioral intention. Nevertheless, the indirect effect of risk controllability (β = 0.024; p > 0.05) (H12b) on pro-environmental behavior through behavioral intention is insignificant. Risk effect (β = 0.019; p < 0.01) (H13a), risk trust (β = 0.017; p < 0.01) (H13c), and risk acceptability (β = −0.04; p < 0.001) (H13d) can significantly and indirectly affect pro-environmental behavior through the chain-mediating effect of attitude and behavioral intention. Risk controllability (β = 0.024; p > 0.05) (H13b) has no significant effect on pro-environmental behavior through the chain-mediating effect of attitude and behavioral intention. Moreover, consumers’ attitude (β = 0.113; p < 0.001), subjective norms (β = 0.058; p < 0.05), and perceived behavioral control (β = 0.091; p < 0.001) significantly and indirectly affect pro-environmental behavior through behavioral intention.

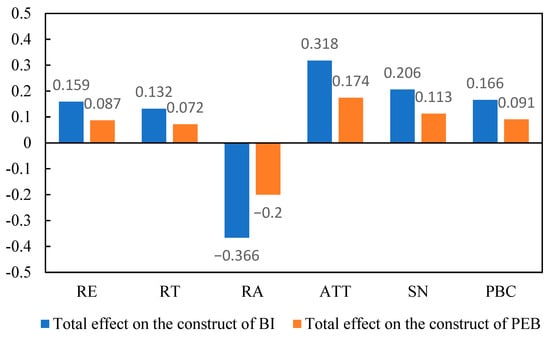

This study also tested the total effects of multidimensional risk perception variables and of attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control on behavioral intention and pro-environmental behavior, and the results are shown in Table A5 and Figure 4. The results show that the total effects of multidimensional risk perception variables and of attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control on behavioral intention are greater than those on pro-environmental behavior. Furthermore, the total effect of risk acceptability on behavioral intention and pro-environmental behavior is the greatest among the multidimensional risk perception variables; this is followed by risk effect and risk trust, while risk controllability has an insignificant total effect on behavioral intention and pro-environmental behavior.

Figure 4.

Total effects on behavioral intention and pro-environmental behavior. Note: The coefficients for the total effect of risk controllability on behavioral intention and pro-environmental behavior are not available in the figure because the total effects of risk controllability on behavioral intention and pro-environmental behavior are not significant.

As shown in Table 4, the SEM accounts for 86% of the variance in behavioral intention (R2 = 0.86) and 27% of the variance in pro-environmental behavior (R2 = 0.27), demonstrating the model’s strong explanatory power. This indicates a gap between behavioral intention and pro-environmental behavior, suggesting that behavioral intention can be converted into pro-environmental behavior to a certain extent.

5. Discussion

Since air pollution impedes societies’ ability to develop sustainably, it has drawn more attention in recent years. Studies on consumers’ pro-environmental behavior from consumers’ risk perception are rare, despite the government’s calls for customers to reduce air pollution through everyday sustainable and pro-environmental consumer behaviors. This study introduces four dimensions of risk perception, including risk effect, risk controllability, risk trust, and risk acceptability. It then integrates multidimensional risk perception variables into the TPB model to construct an extended TPB model, aiming to explore the influence mechanism of consumers’ risk perception of air quality on consumers’ pro-environmental behavior. This paper also aims to explore the applicability of the extended TPB model to the study of pro-environmental behavior and the relationship between behavioral intention and pro-environmental behavior. Moreover, it provides suggestions for the government to enhance consumers’ pro-environmental behavior, thereby mitigating air pollution and helping to achieve the goal of sustainable development.

This study indicates that risk controllability does not affect consumers’ behavioral intention or pro-environmental behavior, which is in line with the findings of Mao et al. [44], who reported that the risk controllability of air pollution had no significant effect on the public WTP for enhancing air quality. This result differs from the classical risk perception theory of Fischhoff and Slovic et al. [46], where controllability usually positively affects intentions by enhancing individuals’ sense of control over behavior. However, the results of this study may be related to the cultural context specific to China. For example, fatalism is more prevalent in East Asian cultures [61], and consumers may tend to accept the status quo rather than take action when they perceive the risk of air pollution as uncontrollable. This psychological mechanism weakens the role of risk controllability in driving behavioral intention. Moreover, the Chinese public’s long-term reliance on the government-led model of environmental pollution control [62] may further reduce individuals’ perceptions of their own control.

The results indicate that risk acceptability significantly and negatively affects consumers’ behavioral intentions and significantly and negatively indirectly affects pro-environmental behavior through behavioral intention. This is in line with the findings of Mao et al. [44]. This is because the average acceptance of poor air quality by consumers is low, and consumers with a low acceptance of poor air quality will have more anxiety about exposure to polluted air, as they worry that polluted air will affect their health. For the sake of their health, consumers will take action to improve air quality. Therefore, the government can enhance consumers’ pro-environmental behavior by educating consumers on the health risks, economic losses, and traffic risks caused by air pollution in various ways to influence consumers’ risk acceptability. For example, the official government account produces a series of sketches or animated shorts on short video platforms (Douyin, Kwai) to explain the possible health risks associated with air pollution, economic losses, and transportation risks caused by air pollution against the backdrop of the local air pollution problem.

The results show that risk effect significantly and positively affects consumers’ behavioral intentions and significantly and positively indirectly affects pro-environmental behavior through behavioral intention, which is consistent with the findings of J. Yang et al. [45]. Longer duration and greater risk impacts stimulate consumers’ awareness of self-protection and their intentions to improve air quality and avoid threats to their lives and safety. However, the government should not encourage consumers’ pro-environmental behavior by increasing the risk effect of air pollution. Instead, the government can allow schools to offer practical courses on environmental protection to teach students how to reduce the negative impacts of air pollution through personal pro-environmental behaviors (e.g., using public transportation, purchasing environmentally friendly products). Additionally, it can ask community councils to put up posters on community bulletin boards to publicize how to reduce air pollution through pro-environmental behaviors. By implementing these initiatives, the government can improve air quality and, hence, reduce the risk effects of air pollution.

This study indicates that risk trust significantly and positively affects consumers’ behavioral intentions and significantly and positively indirectly affects pro-environmental behavior through behavioral intention, which is in line with the findings of Nguyen et al. [50]. Furthermore, trust in the government also affects consumers’ behavioral intentions. Nguyen et al. [50] revealed that the greater the consumers’ level of trust in the government is, the greater the likelihood that consumers will take action in the face of air pollution. Therefore, to eliminate consumers’ information asymmetry and misunderstandings about the government and to strengthen consumers’ trust in the government, the government can set up a real-time data platform for air pollution control to publicize the monitoring data of pollutant sources (e.g., emissions from enterprises) and the progress of treatment (e.g., the rate of achievement of emission reduction targets). The government can regularly organize government–citizen dialogues where the head of the environmental protection department answers questions from the public (e.g., how to deal with industrial pollution) to increase public trust in government actions.

The findings of this study demonstrate the applicability of the extended TPB model to the study of pro-environmental behavior, which aligns with the findings of previous research [63,64]. This paper indicates that attitudes significantly and positively affect consumers’ behavioral intentions, consistent with the findings of Sánchez-García et al. [64] and Savari and Gharechaee [31]. The government can change consumer attitudes toward the improvement of air quality by designing a multi-level incentive mechanism. At the individual level, the government can implement a ”green points system”, whereby citizens accumulate points through low-carbon behaviors (e.g., using public transportation) and redeem them for discounts on public services (e.g., a 5% reduction in metro fares). At the corporate level, the government can offer tax breaks (e.g., a 10% reduction in corporate income tax) to corporations with “green certifications” and prioritize their products in government procurement. At the community level, the government can set up a network of environmental volunteers. In addition, honorary awards should be presented to outstanding environmental volunteer champions. Moreover, this study confirms that the multidimensional variables of risk perception, including risk effect, risk trust, and risk acceptability, significantly and indirectly affect pro-environmental behavior through the chain-mediating effect of attitude and behavioral intention. The rationality of risk perception as an antecedent variable for TPB variables has been justified in prior studies [30,41,65] and is demonstrated again in this study.

The results indicate that subjective norms significantly and positively affect consumers’ behavioral intentions, which is consistent with the findings of Rezaei et al. [24], Lou et al. [63], and Sung-Un Park et al. [66]. An individual’s social group tends to shape his or her thoughts, and the more pressure individuals feel from their social group, the stronger their behavioral intention will be. Especially in China, trust is valued in interpersonal interactions, and people are more willing to follow the advice of their relatives and friends [63]. Hence, subjective norms significantly and positively affect consumers’ behavioral intentions. In this case, the official media can launch “environmental role model” contests on social media (e.g., “Low-Carbon Family of the Year”), and expand their influence through social networks of acquaintances (WeChat) and use social pressure to drive behavioral change.

The results indicate that perceived behavioral control significantly and positively affects consumers’ behavioral intentions because people are more willing to engage in actions that they feel capable of performing. The behavioral intention of these individuals is higher when they have confidence in their time, resources, and skills, as they believe that these factors enable them to take effective actions. This finding is in line with the findings of Rezaei et al. [24], Savari and Gharechaee [31], and Cao et al. [32]. Therefore, the government can compile a guide on pro-environmental behavior for consumers to guide them in performing pro-environmental behaviors to improve air quality. Moreover, subjective norms have a significant indirect positive effect on consumers’ behavioral intention through attitudes and perceived behavioral control. Specifically, attitudes and perceived behavioral control may serve as mediators that influence the relationship between subjective norms and consumers’ behavioral intentions, and this result is consistent with the findings of Sánchez-García et al. [64].

This study indicates that consumers’ behavioral intentions significantly and positively affect pro-environmental behaviors, and that the SEM explains 86% of the variance in behavioral intention (R2 = 0.86) and 27% of the variance in pro-environmental behavior (R2 = 0.27). In this study, the explanatory power of the SEM for pro-environmental behavior was 27% (R2 = 0.27). This result falls within the reasonable range within the field of behavioral sciences, particularly in research grounded in the theory of planned behavior. For instance, in Savari and Gharechaee’s [31] study on farmers’ safe fertilizer-use behavior, the R² for pro-environmental behavior was 0.31. Similarly, Sánchez-García et al. [64] reported an R2 of 0.28 in their research on the willingness to pay to reduce air pollution. Hence, consumers’ behavioral intention is the most critical and direct factor affecting pro-environmental behavior, which is in line with the findings of previous studies [63,67,68]. Furthermore, the results also suggest that behavioral intention is not equivalent to pro-environmental behavior and that behavioral intention can, to a certain extent, be converted into pro-environmental behavior to a certain extent. This is because the generation of behaviors depends not only on behavioral intention but also on other factors influencing pro-environmental behavior. Although the model explains some of the variance in pro-environmental behavior, 73% of the variance is still unexplained, suggesting the presence of other potential influences, such as policy incentives and economic factors. Nigam et al.’s [69] study proved that government policy is a key factor influencing consumers’ use of new energy vehicles. The study by Bahrami et al. [70] demonstrated that despite consumers’ claims that they were willing to pay a premium for green products, actual purchase data showed that price was still a more important decision-making factor than environmental attributes. Due to the complexity of human behavior, it is challenging for a single theoretical model to comprehensively account for all influencing factors. In future research, scholars can further optimize the model by incorporating the aforementioned variables to enhance the explanatory power for pro-environmental behavior.

6. Conclusions and Limitations

6.1. Conclusions

This study explored the mechanisms by which multidimensional risk perception variables, including risk effect, risk controllability, risk trust, and risk acceptability of air pollution, influence consumers’ pro-environmental behavior. The risk effect, risk trust, and risk acceptability of air pollution can indirectly influence pro-environmental behavior through behavioral intention and the chain-mediating effect of attitude and behavioral intention. This study also demonstrated the applicability of the extended TPB model in pro-environmental behavior research. Integrating multidimensional risk perception variables as antecedent variables into the TPB model enhances the explanatory and predictive powers of the TPB model. Moreover, this study explored the relationship between behavioral intention and pro-environmental behavior, showing that behavioral intention is not equivalent to pro-environmental behavior and that behavioral intention can, to a certain extent, be converted into pro-environmental behavior. In addition, this study provides several suggestions for the government. These suggestions aim to enhance consumers’ pro-environmental behavior to improve air quality. Moreover, they aim to reduce air pollution by enhancing consumers’ pro-environmental behavior. By doing so, it is possible to protect the sustainability of ecological environments and to realize sustainable development.

6.2. Limitations

This study also has several limitations. First, it introduced four dimensions of risk perception variables—risk effect, risk controllability, risk trust, and risk acceptability of air pollution—without considering other dimensions. In addition, this study did not systematically measure economic factors such as income and the cost of environmental behavior, nor did it measure policy intervention variables. These omissions may have constrained the explanatory power of the model for pro-environmental behavior (R2 = 0.27). Second, this study was conducted in Harbin, and the results may not be applicable to cities with cultural backgrounds and air-quality conditions different from those of Harbin. Third, this study collected data in October 2019, which may constrain the generalizability of the findings to the current context. This is because consumer behavior, especially environmental behavior, is dynamic.

6.3. Scope for Future Research

In future research, additional dimensions of risk perception variables could be incorporated to explore their influence on consumers’ pro-environmental behavior. By integrating macro-policy data, such as regional environmental subsidies, with micro-economic variables like household income, future studies can more comprehensively elucidate the mechanisms underpinning pro-environmental behavior. Moreover, future investigations should be carried out in regions with diverse cultural backgrounds and varying air quality conditions. Furthermore, future research could build upon this work by integrating longitudinal data to capture the temporal dynamics of risk perception and behavioral intentions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P.; methodology, M.P.; software, M.P.; validation, M.P.; formal analysis, M.P.; investigation, M.P., Z.C., K.C., C.Y., and H.R.; resources, C.A.; data curation, C.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P.; writing—review and editing, M.P., Z.C., K.C., C.Y., C.A., and H.R.; visualization, M.P.; supervision, M.P.; project administration, M.P.; funding acquisition, C.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 71874026).

Institutional Review Board Statement

In accordance with Article 32 of China’s Ethical Review Measures for Life Sciences and Medical Research Involving Human Subjects, ethical review may be waived for research meeting all the following criteria, provided that the study does not harm participants, involve sensitive personal information or commercial interests, and aims to reduce unnecessary burdens on researchers while advancing scientific progress: (i) Public domain data: Research utilizing legally obtained public data or observational data collected without intervention in public settings; (ii) Anonymized data: Studies employing fully anonymized informational datasets; (iii) Pre-existing biospecimens: Research using archived human biological samples that meet all of the following conditions: Specimen sources comply with regulatory and ethical standards. Research scope aligns with original informed consent provisions. Excludes germline cells, embryos, reproductive cloning, chimera studies, or heritable genetic modifications; (iv) Cell line research: Studies using human cell lines obtained from certified biobanks where: Research purposes are within provider-authorized scope. Exclude applications in reproductive cloning, chimera development, or heritable genome editing. This study complies with the above provisions (specify applicable clauses) and therefore does not require separate ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TPB | Theory of planned behavior |

| SEM | Structural equation model |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Statements for the measurement items.

Table A1.

Statements for the measurement items.

| Constructs | Measurement Items |

|---|---|

| Risk Effect | |

| RE1 | I think air pollution has an effect on the appreciation of the landscape. |

| RE2 | I think air pollution has an effect on physical health. |

| RE3 | I think air pollution has an effect on psychological mood. |

| Risk Controllability | |

| RC1 | I think the risk effect of air pollution can be controlled. |

| RC2 | I think the duration of the risk of air pollution can be controlled. |

| RC3 | I think the scope of the risk of air pollution can be controlled. |

| Risk Trust | |

| RT1 | I believe the government’s disclosure about air pollution. |

| RT2 | I believe the government can effectively control air pollution. |

| RT3 | I believe the government will take appropriate and emergency measures to deal with serious air pollution. |

| Risk Acceptability | |

| RA1 | I think the health risks caused by air pollution are acceptable. |

| RA2 | I think the economic losses caused by air pollution are acceptable. |

| RA3 | I think the traffic risks caused by air pollution are acceptable. |

| Attitude | |

| ATT1 | I think the idea of paying to improve air quality is very responsible. |

| ATT2 | I think the idea of paying to improve air quality is very useful. |

| ATT3 | I think the idea of paying to improve air quality is very ecological. |

| Subjective Norms | |

| SN1 | Most people who are important to me would support me in paying to improve air quality. |

| SN2 | Most people who are important to me would want me to pay to improve air quality. |

| SN3 | Most people who are important to me think I should pay to improve air quality. |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | |

| PBC1 | I am confident that if I want to, I can pay to improve air quality. |

| PBC2 | I have the ability to pay to improve air quality. |

| PBC3 | I have the resources, time, and opportunities to pay to help to improve air quality. |

| Behavioral Intention | |

| BI1 | I am willing to pay to improve air quality. |

| BI2 | I would agree to an increase in taxes to improve air quality. |

| BI3 | Paying to improve air quality can make me feel accomplished. |

| Pro-environmental Behavior | |

| PEB1 | I will purchase products with renewable, recycled, or reclaimed labels. |

| PEB2 | I will purchase environmentally friendly products. |

| PEB3 | I will choose to walk, use public transportation, and use other travel modes to reduce air pollution caused by vehicle emissions. |

| PEB4 | I will advise others to stop polluting the air (e.g., setting off firecrackers, burning straw, etc.) |

Table A2.

Comparison table of population proportions in the six urban districts of Harbin and sample allocation.

Table A2.

Comparison table of population proportions in the six urban districts of Harbin and sample allocation.

| City District | Proportion of Population | Sample Size Allocation | Effective Sample Size in Recovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Songbei District | 6.20% | 30 | 30 |

| Daoli District | 21.50% | 106 | 95 |

| Nangang District | 28.93% | 142 | 127 |

| Pingfang District | 4.46% | 22 | 22 |

| Xiangfang District | 20.69% | 102 | 92 |

| Daowai District | 18.22% | 90 | 83 |

Table A3.

Comparing Model Fit Indices in SEM.

Table A3.

Comparing Model Fit Indices in SEM.

| Fit Index | Value | Acceptable Value |

|---|---|---|

| Cmin2/df | <3 | 1.519 |

| RMSEA | <0.05 | 0.034 |

| AGFI | >0.80 | 0.910 |

| GFI | >0.80 | 0.928 |

| SRMR | <0.08 | 0.047 |

| NFI | >0.9 | 0.930 |

| CFI | >0.9 | 0.975 |

| IFI | >0.9 | 0.975 |

| TLI | >0.9 | 0.971 |

| PGFI | >0.50 | 0.745 |

| PNFI | >0.50 | 0.802 |

| PCFI | >0.50 | 0.841 |

Table A4.

Structural model path coefficients and hypothesis testing (direct effects).

Table A4.

Structural model path coefficients and hypothesis testing (direct effects).

| Hypothesis | Path | Std. Estimate | S. E | t Values | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Attitude → Behavioral intention | 0.243 *** | 0.063 | 3.291 | Supported |

| H2 | Subjective norm → Behavioral intention | 0.121 * | 0.053 | 2.003 | Supported |

| H3 | Perceived behavioral control → Behavioral intention | 0.226 *** | 0.037 | 4.543 | Supported |

| H6 | Behavioral intention → Pro-environmental behavior | 0.523 *** | 0.064 | 8.544 | Supported |

| H7 | Risk effect → Behavioral intention | 0.116 * | 0.051 | 2.436 | Supported |

| H8 | Risk controllability → Behavioral intention | 0.045 | 0.047 | 0.920 | Rejected |

| H9 | Risk trust → Behavioral intention | 0.101 * | 0.048 | 2.092 | Supported |

| H10 | Risk acceptability → Behavioral intention | −0.319 *** | 0.055 | −5.327 | Supported |

| Subjective norm → Attitude | 0.412 *** | 0.056 | 7.549 | ||

| Subjective norm → Perceived behavioral control | 0.638 *** | 0.066 | 11.409 | ||

| Risk effect → Attitude | 0.133 ** | 0.064 | 2.641 | ||

| Risk controllability → Attitude | 0.032 | 0.061 | 0.603 | ||

| Risk trust → Attitude | 0.126 * | 0.061 | 2.425 | ||

| Risk acceptability → Attitude | −0.337 *** | 0.062 | −5.863 |

Note: * significant at the 5% level; ** significant at the 1% level; *** significant at the 0.1% level.

Table A5.

Total-effect coefficients on behavioral intention and pro-environmental behavior.

Table A5.

Total-effect coefficients on behavioral intention and pro-environmental behavior.

| Construct | Risk Effect | Risk Controllability | Risk Trust | Risk Acceptability | Attitude | Subjective Norm | Perceived Behavioral Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral intention | 0.159 ** | 0.051 | 0.132 ** | −0.366 *** | 0.318 *** | 0.206 ** | 0.166 *** |

| Pro-environmental behavior | 0.087 ** | 0.028 | 0.072 ** | −0.200 *** | 0.174 *** | 0.113 *** | 0.091 *** |

Note: ** significant at the 1% level; *** significant at the 0.1% level.

References

- Chen, L.; Wang, D.; Shi, R. Can China’s Carbon Emissions Trading System Achieve the Synergistic Effect of Carbon Reduction and Pollution Control? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Ambient (Outdoor) Air Quality and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/zh/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Wallbanks, S.; Griffiths, B.; Thomas, M.; Price, O.J.; Sylvester, K.P. Impact of Environmental Air Pollution on Respiratory Health and Function. Physiol. Rep. 2024, 12, e70006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldeira, D.; Franco, F.; Bravo Baptista, S.; Cabral, S.; Cachulo, M.D.C.; Dores, H.; Peixeiro, A.; Rodrigues, R.; Santos, M.; Timóteo, A.T.; et al. Air Pollution and Cardiovascular Diseases: A Position Paper. Rev. Port. Cardiol. 2022, 41, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, A.J.; Gregoire, A.M.; Niehoff, N.M.; Bertrand, K.A.; Palmer, J.R.; Coogan, P.F.; Bethea, T.N. Air Pollution and Breast Cancer Risk in the Black Women’s Health Study. Environ. Res. 2021, 194, 110651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y. Association between Air Pollutants and Four Major Mental Disorders: Evidence from a Mendelian Randomization Study. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 283, 116887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.; Wang, J. Air Pollution as a Substantial Threat to the Improvement of Agricultural Total Factor Productivity: Global Evidence. Environ. Int. 2023, 173, 107842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonwani, S.; Hussain, S.; Saxena, P. Air Pollution and Climate Change Impact on Forest Ecosystems in Asian Region—A Review. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2022, 8, 2090448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, S.; Qian, Z.; Xie, X.-H.; Luo, Y.; Han, R.; Hou, J.; Wang, C.; McMillin, S.E.; Wu, S.; et al. Short-Term Effects of Air Pollution on Cause-Specific Mental Disorders in Three Subtropical Chinese Cities. Environ. Res. 2020, 191, 110214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Council of China (SCC). Three-Year Plan on Defending the Blue Sky. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2018-07/03/content_5303158.htm (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China (MEE). On the Issuance of the “In-Depth Fight Heavy Pollution Weather Elimination, Ozone Pollution Prevention and Control and Diesel Truck Pollution Control Action Program” Notice. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2022-11/17/content_5727605.htm (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Wang, P. China’s Air Pollution Policies: Progress and Challenges. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2021, 19, 100227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jia, L.; He, P.; Wang, P.; Huang, L. Engaging Stakeholders in Collaborative Control of Air Pollution: A Tripartite Evolutionary Game of Enterprises, Public and Government. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 418, 138074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xia, X.H.; Chen, B.; Sun, L. Public Participation in Achieving Sustainable Development Goals in China: Evidence from the Practice of Air Pollution Control. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 201, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Kurisu, K.; Hanaki, K.; Che, Y. Influential Factors of Public Intention to Improve the Air Quality in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Does Social Value Matter in Energy Saving Behaviors?: Specifying the Role of Eleven Human Values on Energy Saving Behaviors and the Implications for Energy Demand Policy. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 52, 101327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olya, H.G.T.; Bagheri, P.; Tümer, M. Decoding Behavioural Responses of Green Hotel Guests: A Deeper Insight into the Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 2509–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, R.; Sniehotta, F.; Schuz, B. Predicting binge-drinking behaviour using an extended tpb: Examining the impact of anticipated regret and descriptive norms. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006, 42, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, I.J.; Cooper, S.R.; Conchie, S.M. An Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour Model of the Psychological Factors Affecting Commuters’ Transport Mode Use. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Li, H. Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand Individual’s Energy Saving Behavior in Workplaces. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, P.; Staats, H.; Wilke, H.A.M. Situational and Personality Factors as Direct or Personal Norm Mediated Predictors of Pro-Environmental Behavior: Questions Derived from Norm-Activation Theory. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 29, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapsall, S.; Soutar, G.N.; Elliott, W.A.; Mazzarol, T.; Holland, J. COVID-19’s Impact on the Perceived Risk of Ocean Cruising: A Best-Worst Scaling Study of Australian Consumers. Tour. Econ. 2022, 28, 248–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.-H.; Huang, S.-K.; Qin, P.; Chen, X. Local Residents’ Risk Perceptions in Response to Shale Gas Exploitation: Evidence from China. Energy Policy 2018, 113, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, R.; Seidi, M.; Karbasioun, M. Pesticide Exposure Reduction: Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand Iranian Farmers’ Intention to Apply Personal Protective Equipment. Saf. Sci. 2019, 120, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior: Frequently Asked Questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action Control; Kuhl, J., Beckmann, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. ISBN 978-3-642-69748-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Driver, B.L. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Leisure Choice. J. Leis. Res. 1992, 24, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Hansen, H. Determinants of Sustainable Food Consumption: A Meta-Analysis Using a Traditional and a Structura Equation Modelling Approach. Int. J. Psychol. Stud. 2012, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Badgaiyan, A.J. Towards Improved Understanding of Reverse Logistics—Examining Mediating Role of Return Intention. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 107, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.Y.; Chang, P.-J. The Effect of Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) Risk Perception on Behavioural Intention towards ‘Untact’ Tourism in South Korea during the First Wave of the Pandemic (March 2020). Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1017–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savari, M.; Gharechaee, H. Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior to Predict Iranian Farmers’ Intention for Safe Use of Chemical Fertilizers. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Li, F.; Zhao, K.; Qian, C.; Xiang, T. From Value Perception to Behavioural Intention: Study of Chinese Smallholders’ pro-Environmental Agricultural Practices. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 315, 115179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruijn, G.-J. Understanding College Students’ Fruit Consumption. Integrating Habit Strength in the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Appetite 2010, 54, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Tang, Y. A Study on the Mechanism of Digital Technology’s Impact on the Green Transformation of Enterprises: Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Mosquera, N. Gender Differences, Theory of Planned Behavior and Willingness to Pay. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekola, P.M.E. The Theory of Planned Behavior in Predicting Willingness to Pay for Abatement of Forest Regeneration. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2001, 14, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.R.; Little, V.J. Context, Culture and Green Consumption: A New Framework. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2016, 28, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lili, D.; Ying, Y.; Qiuhui, H.; Mengxi, L. Residents’ Acceptance of Using Desalinated Water in China Based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB). Mar. Policy 2021, 123, 104293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, L.; Mou, M.; Tang, H.; Gao, S. Exploring Preference and Willingness for Rural Water Pollution Control: A Choice Experiment Approach Incorporating Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 332, 117408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.L. Understanding Preventative Behavior During Prolonged Crises: The Role of Color-Coded Maps and Pandemic Fatigue in COVID-19 Risk Management. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 108, 104554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Q. Research on the Impact of Media Credibility on Risk Perception of COVID-19 and the Sustainable Travel Intention of Chinese Residents Based on an Extended TPB Model in the Post-Pandemic Context. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadian Pouri, M.; Rahimian, M.; Gholamrezai, S. Investigating the Dietary Intentions of Iranian Tourists Regarding the Consumption of Local Food. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1226607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. Perception of Risk. Science 1987, 236, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, B.; Ao, C.; Cheng, Y.; Jiang, N.; Xu, L. Exploring the Role of Public Risk Perceptions on Preferences for Air Quality Improvement Policies: An Integrated Choice and Latent Variable Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 269, 122379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zou, L.; Lin, T.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H. Public Willingness to Pay for CO2 Mitigation and the Determinants under Climate Change: A Case Study of Suzhou, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 146, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischhoff, B.; Slovic, P.; Lichtenstein, S.; Read, S.; Combs, B. How Safe Is Safe Enough? A Psychometric Study of Attitudes Towards Technological Risks and Benefits. Policy Sci. 1978, 9, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P.; Fischhoff, B.; Lichtenstein, S. The Psychometric Study of Risk Perception. In Risk Evaluation and Management; Covello, V.T., Menkes, J., Mumpower, J., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1986; pp. 3–24. ISBN 978-1-4612-9245-6. [Google Scholar]

- Eser, N.; Yavuzalp Marangoz, A. Kriz Dönemlerinde Risk Algısının Tüketici Davranışlarına Etkisi: Deprem Örneği. Alanya Akad. Bakış 2024, 8, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, S.; Shao, Z.; Fang, M.; Yang, L.; Liu, R.; Bi, J.; Ma, Z. Spatial Distribution of the Public’s Risk Perception for Air Pollution: A Nationwide Study in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 655, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.M.; Phuc, H.N.; Tam, D.T. Travel Intention Determinants During COVID-19: The Role of Trust in Government Performance. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China (MEE). National Ambient Air Quality Conditions for July 2024. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/ywdt/xwfb/202408/t20240821_1084322.shtml (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of Tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramayah, T.; Lee, J.W.C.; Lim, S. Sustaining the Environment Through Recycling: An Empirical Study. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 102, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.R.; Yi, Y. On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, S.; Batista-Foguet, J.M.; Van Wunnik, L. Exploring the Public’s Willingness to Reduce Air Pollution and Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Private Road Transport in Catalonia. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 646, 850–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Huang, G.; Yin, X.; Gong, Q. Residents’ Waste Separation Behaviors at the Source: Using SEM with the Theory of Planned Behavior in Guangzhou, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 9475–9491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayhew, M.J.; Hubbard, S.M.; Finelli, C.J.; Harding, T.S.; Carpenter, D.D. Using Structural Equation Modeling to Validate the Theory of Planned Behavior as a Model for Predicting Student Cheating. Rev. High. Educ. 2009, 32, 441–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1992, 1, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhont, F. Adaptability and Fatalism as Southeast Asian Cultural Traits. SUVANNABHUMI 2017, 9, 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Kou, P.; Jiao, Y. How Does Public Participation in Environmental Protection Affect Air Pollution in China? A Perspective of Local Government Intervention. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2022, 31, 1095–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, S.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, D. Foresight from the Hometown of Green Tea in China: Tea Farmers’ Adoption of pro-Green Control Technology for Tea Plant Pests. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 320, 128817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, M.; Zouaghi, F.; Lera-López, F.; Faulin, J. An Extended Behavior Model for Explaining the Willingness to Pay to Reduce the Air Pollution in Road Transportation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 128134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiyoso, W. Wilopo Social Distancing Intentions to Reduce the Spread of COVID-19: The Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-U.; Ahn, H.; So, W.-Y. Role of COVID-19 Risk Perception in Predicting the Intention to Participate in Exercise and Health Behaviors among Korean Men. J. Men’s Health 2023, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, B. The Determinants of Cucumber Farmers’ Pesticide Use Behavior in Central Iran: Implications for the Pesticide Use Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 205, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, G.M.L. Planned Behavior and Social Capital: Understanding Farmers’ Behavior Toward Pressurized Irrigation Technologies. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 243, 106524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigam, N.; Senapati, S.; Samanta, D.; Sharma, A. Consumer Behavior towards New Energy Vehicles: Developing a Theoretical Framework. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahrami Khodabandeh, R. Role of Green Marketing in the Adoption of Intelligent Food Containers. Master’s Thesis, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).