1. Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) has become an integral aspect of business strategy, particularly in consumer-driven markets such as cosmetics. The increasing awareness of social and environmental issues among consumers has led to a paradigm shift in how companies approach their CSR initiatives. This shift is particularly pronounced among younger generations, such as Millennials and Generation Z, who prioritize ethical consumption and are more likely to support brands that align with their values [

1].

The impact of CSR on consumer behavior is further amplified by the rise of social media as a platform for brand communication. Lyu et al. [

2] note that social media marketing can effectively enhance the visibility of CSR initiatives, thereby influencing consumer purchasing behavior. The interactive nature of social media allows consumers to engage with brands and share their perceptions of CSR efforts, creating a community of advocates who support socially responsible practices. This dynamic not only strengthens consumer–brand relationships but also encourages companies to be more accountable for their CSR commitments. These ongoing trends underscore the necessity for companies to not only engage in CSR activities but also effectively communicate these efforts to their target audiences.

The cosmetics industry, in particular, has been scrutinized for its environmental impact, including issues related to sourcing, production, and packaging. As consumers become more informed about the ecological footprint of their purchases, they increasingly demand transparency and accountability from brands. Studies have shown that CSR initiatives, particularly those focused on sustainability and ethical practices, can enhance brand perception and foster consumer loyalty [

3,

4]. For instance, brands that actively engage in environmentally friendly practices, such as using sustainable materials or reducing waste, are often viewed more favorably by consumers, which can translate into increased purchase intentions [

5,

6]. This relationship highlights the importance of CSR as a strategic tool for differentiation in a competitive market.

Recent research suggests that emotional engagement, such as feelings of pride or collective guilt, can significantly enhance the impact of CSR on consumer behavior [

7,

8]. When consumers perceive a brand as genuinely committed to social and environmental causes, they are more likely to form positive attitudes toward the brand, which can lead to increased purchase intentions and advocacy behaviors [

9,

10]. This emotional resonance is particularly relevant in the cosmetics market, where brand loyalty is often driven by personal values and identity.

While prior research has examined the general relationship between CSR and consumer behavior, there is a need for more nuanced investigations that differentiate between the effects of various CSR dimensions. This study addresses this gap by explicitly focusing on social and environmental CSR and exploring their potential interactive effects. This focus aligns with the findings of Bae and Lee [

11] and Zaborek [

12], who highlighted the differential effects of CSR activities on firm performance, emphasizing the need to understand the specific impact of each CSR dimension. While many studies have focused on the individual impacts of social or environmental initiatives, there is a growing need to explore how these dimensions interact to shape consumer perceptions and behaviors [

13,

14]. For example, a brand that promotes both social equity and environmental sustainability may resonate more strongly with consumers than one that focuses on only one aspect. Understanding this interplay can provide valuable insights for marketers aiming to craft comprehensive CSR strategies that appeal to a broader audience.

Recent studies, such as those by Singh et al. [

15] and Hojnik et al. [

16], further emphasize the importance of CSR’s role in shaping purchase behavior, particularly when considering contextual variables and consumer heterogeneity. This oversight leaves unanswered questions about whether firms should prioritize one CSR dimension over another or integrate both strategically to maximize consumer goodwill. Additionally, existing research largely overlooks the moderating role of intrinsic and extrinsic consumer motives, price sensitivity, and sustainable consumption habits, which may shape the effectiveness of CSR efforts [

17,

18]. Moreover, Konalingam et al. [

19] underscore the importance of consumer attributions in evaluating CSR initiatives, highlighting the need for more experimental investigations to untangle these effects. In particular, integration of motivational dimensions with CSR research remains underexplored in experimental settings that allow for precise control and measurement of these variables.

To address these gaps, this study employed an experimental design that manipulated social CSR, environmental CSR, and price to analyze their direct and interactive effects on consumer purchase intentions. Specifically, it examined how consumers’ purchasing decisions are influenced by their knowledge of a company’s social and environmental performance, with a focus on hair shampoo products.

Furthermore, this research explored the moderating role of consumer motives (intrinsic/extrinsic, hedonic/utilitarian) and sustainable consumption habits, adding another layer of complexity and contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of the factors that shape consumer responses to CSR initiatives.

The practical contributions of this study are multifaceted. First, it provides actionable insights for businesses in the cosmetics market by demonstrating how a balanced emphasis on social and environmental CSR can synergistically enhance consumer purchase intentions. This finding underscores the importance of integrating both dimensions into CSR strategies, rather than prioritizing one over the other. Second, this study highlights the significance of consumer motivations, particularly intrinsic motives, in mediating CSR effects. Companies can leverage this understanding to tailor their CSR communications, emphasizing authenticity and alignment with consumers’ personal values. Finally, the findings offer guidance for pricing strategies by revealing how price sensitivity interacts with CSR initiatives, helping businesses optimize their value propositions for ethically conscious consumers.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. The next section briefly looks into the challenges and opportunities of CSR adoption in the cosmetics industry. Next we review the theoretical background and formulate the research hypotheses. This is followed by the research methods section, which details the experimental design and measurement approach. The findings section presents the key results and their implications, while the discussion provides an interpretation of these results in light of the existing literature. Finally, the article concludes with practical recommendations and directions for future research.

2. Corporate Social Responsibility in the Cosmetics Industry

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) has become a pivotal aspect of the cosmetics industry, reflecting a commitment to ethical practices, environmental sustainability, and social accountability. As consumers increasingly demand transparency and responsibility from brands, CSR initiatives have evolved from optional endeavors to essential components of corporate strategy. This shift is particularly evident in the cosmetics sector, where companies are integrating CSR into their operations to meet consumer expectations and regulatory requirements.

Environmental sustainability is a core focus of CSR in the cosmetics industry. Companies are adopting practices that minimize their environmental impact, such as reducing carbon footprints, implementing sustainable sourcing, and promoting eco-friendly packaging. For instance, L’Oréal achieved an 81% reduction in CO

2 emissions at its manufacturing and distribution facilities between 2005 and 2020 and aspires to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 [

20]. Similarly, Christian Dior aims to slash its operational emissions by 46% by 2030 compared to 2019 levels and to power all of its facilities with 100% renewable energy and biogas by 2023 [

20].

However, challenges persist in achieving genuine sustainability. A study by Lee and Jeong [

21] found that while consumers positively perceive CSR activities related to environmental sustainability, there is often skepticism regarding the authenticity of these initiatives. This skepticism underscores the need for companies to ensure that their CSR efforts are not only well-communicated but also transparently implemented to build brand trust.

Ethical sourcing and ingredient transparency are critical elements of CSR in cosmetics. Consumers are increasingly concerned about the origins of ingredients and the ethical implications of their production. A study by Vuković [

22] highlights that modern consumers, particularly Generation Z, prioritize brands that demonstrate social responsibility, including ethical sourcing and transparency in ingredient lists. This demographic’s purchasing decisions are significantly influenced by a brand’s commitment to ethical practices, reflecting a broader trend toward conscientious consumption.

It seems that these consumer concerns are not properly addressed by the industry. A report by Good on You analyzed 239 beauty brands and found that while 75% disclose ingredient lists, many lack transparency regarding specific components, such as fragrance ingredients. Additionally, 78% of brands lack certification proving they do not test on animals, highlighting a significant gap in ethical practices. These findings underscore the need for more rigorous and standardized regulations to ensure transparency and accountability in the industry [

23].

This apparent lack of transparency is related to the concept of greenwashing, where companies misleadingly portray their products as environmentally friendly. This is particularly concerning in the cosmetics sector, where the use of natural and organic ingredients is often marketed as a hallmark of sustainability, despite the presence of harmful chemicals in the products. As noted by Nguyen et al. [

24], many CSR practices in the cosmetics industry can be superficial, serving more as marketing strategies than genuine efforts toward sustainability. This undermines the fundamental goals of sustainable development and can lead to consumer skepticism regarding the authenticity of CSR claims. Considering that consumers are becoming more adept at identifying insincere CSR efforts, companies that fail to demonstrate genuine commitment are exposed to a serious risk of reputational damage.

In conclusion, CSR in the cosmetics industry encompasses a broad spectrum of practices aimed at promoting environmental sustainability, ethical sourcing, and social responsibility. As consumer awareness and demand for responsible business practices continue to grow, companies must navigate the challenges and seize the opportunities presented by CSR to build trust, loyalty, and the industry’s sustainability.

3. Theoretical Background and Research Hypotheses

A substantial body of literature supports the notion that CSR engagement positively influences consumer purchase intentions [

15,

16]. Companies that actively engage in CSR initiatives tend to foster stronger brand trust, consumer loyalty, and perceived brand authenticity [

25]. However, consumer responses to CSR initiatives are not uniform. While some consumers respond positively to CSR efforts, others exhibit skepticism, particularly when CSR claims appear misaligned with corporate actions [

26,

27].

A disparity often exists between consumers’ expressed support for ethical practices and their actual purchasing behavior. Factors such as price sensitivity, convenience, and habitual purchasing can overshadow CSR considerations, leading to a weaker correlation between CSR engagement and purchase decisions. Vermeir and Verbeke [

28] highlighted this gap, noting that positive attitudes toward sustainability do not always translate into sustainable purchasing actions.

From a psychological perspective, CSR engagement strengthens brand–consumer relationships by appealing to ethical consumerism, where buyers seek to align their purchasing behaviors with personal values [

29]. Several studies suggest that brands perceived as socially responsible enjoy greater customer commitment and fewer switching intentions [

30]. The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) further explains this relationship by positing that an individual’s behavioral intentions are influenced by their attitudes, perceived control, and subjective norms [

31].

Another theoretical framework supporting this proposition is signaling theory, which suggests that CSR activities function as quality signals that influence consumer decision-making [

32]. Companies engaging in CSR send positive cues about corporate ethics and responsibility, enhancing brand equity and trustworthiness [

11]. Empirical studies in the cosmetics industry indicate that CSR perceptions not only shape brand evaluations but also affect price tolerance, as ethically engaged consumers may be willing to pay a premium for socially responsible brands [

22].

Emotional benefits associated with CSR-aligned brands can mitigate cognitive dissonance, a psychological state where conflicting beliefs and behaviors create discomfort. Achabou [

33] discusses how cognitive dissonance theory posits that consumers may employ various strategies to reconcile their beliefs with their purchasing behaviors, often leading to a preference for brands that reflect their ethical standards. This is further supported by the work of Wagner et al. [

34], which illustrates that consumers are increasingly prioritizing the social responsibility of firms in their purchasing decisions, thereby enhancing brand image and consumer loyalty. The emotional gratification from supporting ethical brands not only reduces cognitive dissonance but also fosters a deeper connection between consumers and the brands they choose to support.

Additionally, research indicates that younger generations, particularly Millennials and Generation Z, who are consistent with this study’s sample, demonstrate heightened responsiveness to CSR initiatives [

35]. These cohorts prioritize sustainability and ethical transparency, making CSR engagement a strategic imperative for brands aiming to secure long-term customer loyalty. Given that younger consumers increasingly utilize digital platforms to scrutinize corporate behavior, brands with strong CSR commitments benefit from enhanced online reputations and positive word-of-mouth effects.

Taken together, these theoretical insights and empirical findings lead to the following first hypothesis:

H1. Social CSR and environmental CSR engagement of a company are positively associated with consumer purchase intentions for products from that company.

The exploration of the synergistic effect of social and environmental corporate social responsibility (CSR) on consumer purchasing decisions presents a notable research gap in the current literature. While there is a growing body of evidence examining the individual impacts of social and environmental CSR on consumer behavior, studies that specifically investigate their combined effects remain limited. For instance, Woo and Kim [

36] found that consumer attitudes toward green food products are significantly influenced by their environmental concerns, suggesting that green perceived value (GPV) plays a crucial role in shaping purchase intentions. Similarly, Ng’s research indicates that CSR expectations positively impact the purchase intentions of social enterprise products, highlighting the importance of perceived social responsibility in consumer decision-making [

37]. However, these studies primarily focus on the isolated effects of either social or environmental CSR, leaving the interaction between the two dimensions largely unexplored.

Evidence of the diverse effects of different CSR types can be found in Pérez et al. [

38], who showed that social value can only be influenced through social CSR initiatives, while environmental CSR does not similarly affect social value perceptions. In their study, social value represents social benefits one could gain from using or consuming a product in public, which is consistent with extrinsic motives for sustainable consumption. In a related study, Behre and Cauberghe [

39] investigated how ethical (social) and environmental cues affect three kinds of brand perceptions: emotional (representing intrinsic motives), social (corresponding to extrinsic motives), and functional (associated with utilitarian motives). They carried out a two-by-two between-subjects experiment in which they presented participants with pictures from an online store of a fictional fashion brand. Their findings indicate that environmental vs. social sustainability cues resulted in much more positive brand attitudes (interestingly, the direct effect of social cues on brand attitude was negative). The enhanced brand attitude for environmental CSR was achieved through the moderation of social brand values (linked to personal image benefits), which was not observed for social CSR. These findings underscore the potential disconnect between social and environmental CSR, suggesting that more research is needed to explore how these dimensions can be integrated to enhance consumer perceptions and purchasing decisions. As such, we put forward the following hypothesis:

H2. Social CSR and environmental CSR interact to influence purchase intentions, such that the positive effect of one dimension is enhanced when the other is also high.

Several studies indicate that higher product prices can diminish the positive effects of CSR on purchase intentions. For instance, Liu and Xu [

29] found that when consumers are presented with CSR information, their purchase intentions can be significantly influenced by the perceived value of the CSR initiatives. They noted that when prices are perceived as high, the positive impact of CSR on purchase intentions diminishes, suggesting that price can act as a moderating factor. This aligns with findings from Tong and Su [

40], who reported that price negatively impacts consumers’ purchase intentions, particularly when CSR reputation is considered alongside product pricing. Their research indicates that consumers may prioritize price over CSR attributes when making purchasing decisions, especially in competitive FMCG markets.

On the other hand, some research suggests that CSR can maintain or even enhance purchase intentions despite higher prices. For one, Siyal et al. [

41] argue that when brands effectively position themselves as environmentally responsible, consumers may be willing to overlook higher prices in favor of supporting sustainable practices. This indicates that strong CSR messaging can mitigate the negative effects of price on purchase intentions, implying that consumers may prioritize ethical considerations over cost in certain contexts.

Moreover, Ng’s [

37] research highlights that CSR expectations can positively influence purchase intentions, even when prices are elevated. Therefore, consumers may perceive the value of CSR initiatives as justifying higher prices, particularly for products that align with their ethical and moral principles. Similarly, Huang et al. found that consumers increasingly seek products that reflect their environmental and ethical values, indicating that CSR can enhance purchase intentions regardless of price [

42]. This implies that while price is a significant factor, it may not always negatively moderate the effects of CSR on purchase intentions. Zaborek and Nowakowska [

43] provide even more striking evidence for a positive moderating role of price. In an experiment that presented respondents with various shopping scenarios involving a hypothetical fast-fashion brand, higher prices led to increased purchase intentions for the brand with the highest level of CSR engagement. The authors explain this effect by suggesting that consumers may not trust claims of high CSR involvement when retail prices appear too low. This may imply that consumers are aware of the concept of greenwashing and do not trust CSR cues that they consider unrealistic. Accounting for the above examples of recent research, we propose that:

H3. Product price negatively moderates the effects of social and environmental CSR on purchase intentions.

The conceptual model of this study was expanded to incorporate motivational variables identified by previous research as potential moderators of the relationship between CSR engagement and purchase intentions. These include intrinsic/extrinsic and utilitarian/hedonic motivations. While examining these variables was not the primary focus of this project, considering their possible moderating effects enhances our understanding of how consumers respond to CSR cues during their shopping experiences. This approach may reveal spurious relationships or uncover suppressed associations, thereby providing a more nuanced perspective on the interplay between CSR initiatives and consumer behavior.

Several studies indicate that both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations can enhance the positive effects of CSR on purchase intentions. Wallach and Popovich [

18] found that when consumers perceive CSR initiatives as authentic and aligned with their values (intrinsic motives), alongside tangible benefits (extrinsic motives), their intention to purchase increases. Similarly, Pham et al. [

17] demonstrated that intrinsic motivations, such as personal values and environmental concerns, synergistically interact with extrinsic motivations like social status and peer influence to promote sustained pro-environmental consumer behaviors. This indicates that when consumers are motivated by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors, they are more likely to respond favorably to CSR initiatives, thereby enhancing purchase intentions.

On the other hand, some studies present a more neutral perspective, suggesting that the relationship between CSR and purchase intentions may not be significantly affected by intrinsic or extrinsic motives. For example, Hwang’s [

44] exploration of sustainable fashion consumption highlights that while intrinsic motivations are important, the influence of extrinsic motivations can be context-dependent, leading to mixed results regarding their overall impact on purchase intentions. Similarly, Zaborek and Nowakowska [

43] found extrinsic motives to be stronger drivers of purchase intentions than intrinsic values, which were found for certain consumer groups to diminish purchase intentions in response to a brand’s CSR engagement. Considering the most plausible relationship patterns, we hypothesize that:

H4a. Intrinsic motives for sustainable consumption moderate the relationship between social and environmental CSR and purchase intentions.

H4b. Extrinsic motives for sustainable consumption moderate the relationship between social and environmental CSR and purchase intentions.

Based on published research, the effect of hedonic and utilitarian consumption motives on the link between CSR engagement and purchase intentions seems to be less straightforward than the role of extrinsic and intrinsic motivations. Some evidence suggests that utilitarian motives can undermine the positive effects of CSR on purchase intentions. As an example, Pérez et al. [

45] found that while hedonic motivations can enhance consumer responses to CSR, utilitarian motivations may not have the same effect, indicating that a focus on functional benefits can detract from the emotional appeal of CSR initiatives. Interestingly, Lin et al. [

46] observed that while hedonic and utilitarian shopping values are associated with CSR expectations, they were found to be negative predictors of green purchase intentions, suggesting that while both types of motives can influence consumer perceptions of CSR, their direct impact on purchase intentions may vary. On the other hand, Zaborek and Nowakowska [

43], investigating both motivation taxonomies, showed that hedonic and utilitarian motives did not significantly contribute to the model explaining the relationship between CSR and purchase intentions in addition to the variance already explained by extrinsic and intrinsic drivers.

To account for possible interactive patterns, we put forward the following hypothesis:

H5a. Hedonic motives for buying cosmetics moderate the relationship between social and environmental CSR and purchase intentions.

H5b. Utilitarian motives for buying cosmetics moderate the relationship between social and environmental CSR and purchase intentions.

Sustainable consumption is a concept that encompasses the use of goods and services in a manner that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. It emphasizes the importance of minimizing the negative impacts on the environment and society while enhancing the quality of life [

16].

Several studies indicate that consumers’ engagement in sustainable consumption positively influences the relationship between their perception of CSR and purchase intentions. For instance, Olšanová et al. [

47] emphasize that understanding how CSR activities influence consumer responses is critical, particularly in the luxury sector, where consumers’ perceptions of CSR can significantly affect their purchase intentions. Given that individuals who engage in sustainable practices in their daily lives tend to hold more positive attitudes toward sustainability, it is plausible that consumers exhibiting sustainable behavior are more likely to respond favorably to brands with strong CSR commitments. Indeed, self-reported past sustainable behaviors may be a more reliable indicator of this attitude than stated opinions on sustainability-related themes.

Similarly, Piligrimienė et al. [

48] found that consumer engagement in sustainable consumption is positively correlated with loyalty and purchase intentions. Their research indicates that when consumers actively engage in sustainable practices, they are more likely to perceive brands’ CSR efforts as credible and aligned with their values, thereby enhancing their intention to purchase from those brands. This suggests that engagement in sustainable consumption can act as a catalyst, strengthening the positive effects of CSR on purchase intentions.

Moreover, Razzaq et al. [

49] highlight that consumers who are motivated by both utilitarian and hedonic values are more likely to engage in sustainable fashion consumption when they perceive brands as socially responsible. This indicates that engagement in sustainable consumption can enhance the relationship between CSR perceptions and purchase intentions, particularly in contexts where consumers seek to align their purchases with their values.

However, some studies present a more neutral perspective, suggesting that the relationship between CSR perceptions and purchase intentions may not be significantly affected by engagement in sustainable consumption. For example, Hsu et al. [

50] explored the role of CSR in influencing perceived value and purchase intentions but noted that the effects of CSR may vary depending on consumer engagement levels. Accordingly, while there may be some influence, the moderating effect of sustainable consumption engagement is not always straightforward and can depend on other contextual factors.

Some research provides even stronger evidence that engagement in sustainable consumption may not always enhance the relationship between CSR perceptions and purchase intentions. For instance, Yamoah and Acquaye [

51], investigating the attitude–behavior gap based on a large real-life consumer purchase dataset, concluded that despite high levels of environmental awareness, consumers’ actual purchasing behavior of sustainable products was restricted by a number of inhibiting factors. This implies that even when consumers are engaged in sustainable practices, their perceptions of CSR may not translate into increased purchase intentions, highlighting several barriers such as premium pricing, product availability, variety, and quality.

Moreover, Čapienė et al. [

52] discussed how pro-environmental and pro-social engagement can vary among consumers, suggesting that those prioritizing personal welfare may not be as influenced by CSR perceptions in their purchasing decisions. This indicates that engagement in sustainable consumption may not uniformly enhance the relationship between CSR and purchase intentions, as individual motivations can significantly impact consumer behavior.

In conclusion, while substantial evidence supports the notion that consumers’ engagement in sustainable consumption moderates the relationship between their perception of a brand’s involvement in social and environmental CSR and their purchase intentions, there are also indications of neutral and even contradictory effects. This complexity underscores the need for further research to clarify the conditions under which this moderation occurs; hence, we hypothesize:

H6. Sustainable consumption moderates the relationship between social and environmental CSR and purchase intentions.

To summarize the theoretical background and hypothesis development, we present the empirical focus of this study in

Figure 1. It illustrates how social CSR, environmental CSR, and price influence consumer purchase intentions. The figure also incorporates the moderating effects of consumer motivations and sustainable consumption habits, highlighting the interplay of these factors. Each pathway in the model corresponds to a specific hypothesis tested in this study, signifying the proposed direct, interactive, and moderating effects.

4. Research Methods

This study employed a scenario-based experimental design, also known as a vignette experiment. This approach involves presenting participants with hypothetical scenarios or vignettes that depict a realistic situation or context, allowing researchers to examine the impact of manipulated variables on their responses [

53]. Following the recommendations of Wiegmann et al. [

54], we conducted a pilot test with ten university students who matched the characteristics of our target population. Their feedback enabled us to refine the scenarios, improving internal consistency, linguistic clarity, and participant engagement. This iterative process enhanced the validity of our experimental design.

For the final data collection, respondents were randomly assigned to different scenarios depicting a hair shampoo purchase situation. In these scenarios, we systematically manipulated three key factors: social CSR, environmental CSR, and price, allowing us to examine their individual and combined effects on consumer decision-making.

4.1. Manipulation Variables

Social CSR: This factor represented the company’s commitment to social causes. Participants were either presented with a scenario where the company was described as having a poor record in social responsibility (e.g., lack of support for local communities, no charitable programs) or a scenario where the company was described as being highly engaged in social responsibility (e.g., supporting local communities, active in charitable work).

Environmental CSR: This factor reflected the company’s efforts toward environmental sustainability. Participants encountered scenarios where the company either exhibited low environmental responsibility (e.g., no use of biodegradable packaging, no use of renewable energy) or high environmental responsibility (e.g., use of biodegradable packaging, use of renewable energy in production).

Price: The price of the shampoo was also manipulated. Participants were presented with scenarios where the shampoo was either in a moderately low price range (20–40 PLN) or a moderately high range (41–80 PLN).

The combination of these factors resulted in a total of eight unique scenarios (2 Social CSR × 2 Environmental CSR × 2 Price).

To provide a better understanding of our design choices, here is an English translation of Scenario 6, representing a shopping situation involving a brand with a high social engagement, high environmental engagement and a high price:

“Imagine you want to buy shampoo for yourself. You go to a drugstore, compare the available options, and find one that meets your expectations regarding scent, cleansing and care properties, and other features of the shampoo that are important to you.

The price of the shampoo is in the range of 40 to 80 PLN.

The shampoo’s manufacturer is a company you recently read about, which is rated as the best in its industry in terms of corporate social responsibility. This includes supporting local communities, engaging in charitable activities, maintaining high transparency in its operations, and supporting initiatives that promote workplace diversity and ensure equal treatment of employees regardless of gender, ethnicity, etc.

The manufacturer of this shampoo also stands out positively compared to other cosmetic companies in terms of its environmental impact. This includes using biodegradable or reusable packaging, environmentally friendly formulations, renewable energy in production processes, and extensive collaboration with environmental organizations.

Would you be willing to purchase this product, or would you continue looking for another?”

Having read the scenario they were assigned to, the respondents were asked to determine how likely they were to buy the product described in it. This purchase intention was the study’s dependent variable, measured on a seven-point scale from 1 (“I definitely would not buy this shampoo”) to 7 (“I definitely would buy it”).

4.2. Operationalization of Constructs

The data were collected using an online questionnaire administered through Google Forms. We created eight different versions of the questionnaire, with each version corresponding to a different scenario. While the scenario description varied across these versions, the remainder of the questionnaire was identical. It included 30 Likert-type statements and 16 binary items designed to measure the study’s reflective and formative constructs. At the end of the form there were demographic questions including gender, age and study major. Completing the questionnaire took approximately 20 min. This structured approach ensured consistency across responses while allowing for an effective comparison of the different experimental conditions.

The four reflective constructs of the study were measured with 7-point Likert items, all validated in published past research (extrinsic motives, intrinsic motives, hedonic motives and utilitarian motives).

The distinction between reflective and formative constructs has been widely debated in the literature. While some scholars argue that constructs are inherently reflective or formative, others, including Hanafiah [

55], advocate for a classification approach grounded in three key criteria: (i) the fundamental nature of the construct, (ii) the direction of causality, and (iii) the properties of the associated indicators. This classification is based on the following characteristics: the construct exists independently of its measurement items, causality flows from the latent construct to its indicators, and the construct’s validity is unaffected by the number or type of items used to measure it. One statistical implication of this is the need to use factor analysis in estimating construct scores for individual respondents.

The following table summarizes the measurement scales used for the reflective constructs in this study. For brevity,

Table 1 includes the content of the Likert-scale items, their corresponding literature sources, as well as factor loadings obtained through confirmatory factor analysis, which reflect the strength of the association between the indicator item and its construct. Factor loadings will be discussed later together with other metrics of reliability and validity.

In contrast to the other independent constructs, sustainable consumption was conceptualized as a formative variable, defined by its individual indicators—specific sustainable actions reported by respondents—rather than serving as their underlying cause [

64]. Unlike reflective constructs, formative constructs do not require their indicators to be correlated. Sustainable consumption represents a variety of eco-friendly practices, such as recycling or opting for environmentally conscious products. To measure this construct, we employed a 16-item dichotomous scale, where respondents marked whether they regularly performed specific sustainable actions. Sample items included statements like “I make an effort to minimize food waste” (adapted from [

65]) and “I prioritize products that are more environmentally friendly when choosing between similar options” (adapted from [

48]). Composite scores for sustainable consumption were calculated by summing the responses to all items, which was subsequently standardized for inclusion in regression analyses.

4.3. Data Collection Method

Data were gathered using cluster sampling. Initially, a list of active student groups at both universities was compiled. Each group was assigned a unique range of natural numbers, with the range size proportional to the group size. This proportional allocation ensured that larger groups had a higher probability of selection, thereby maintaining the representativeness of the sample. Subsequently, 40 groups were randomly selected using Excel’s RANDBETWEEN function.

This number of groups was chosen to yield a sample size of at least 300 respondents, a common practice in consumer research. In the context of multiple regression analysis, a sample of about this size is often suggested to ensure sufficient statistical power to detect weak to moderate relationships. For example, Bujang et al. [

66] recommended collecting data from 300 subjects to accurately represent regression parameters in the target population. Consequently, the resultant sample can be considered representative of the student populations at the two universities, allowing for the generalization of the results using inferential statistics.

This research was designed and conducted in a manner consistent with established ethical guidelines. Data collection occurred during regular class sessions; however, participation in the study was not part of the course syllabus, and individuals were able to opt out without disclosing this to the interviewers. Participants were informed about the topic of the study in general terms to adhere to informed consent principles without introducing bias into the results. In particular, students were informed about the academic nature of the project and the intent to publish the findings.

This study followed an anonymous online survey format, ensuring participant confidentiality and eliminating the collection of personally identifiable information. Therefore, according to Polish regulations, formal ethical approval from the authors’ respective universities’ ethics review boards was not required. The survey instrument employed non-invasive questions that posed no risk to participants’ well-being. Additionally, the study utilized previously validated scales from established research, which have not been associated with any ethical concerns.

During data collection, a link to the online survey was displayed on the screen, and students completed the questionnaires on their personal electronic devices (laptops and smartphones) under supervision. Entering the link into a browser displayed a webpage with a randomization algorithm that assigned respondents to one of eight scenarios with accompanying scaled questions.

4.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using the R environment (version 4.4.2). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was initially employed to establish the validity of the measurement model and extract latent constructs representing the variables from the conceptual model. Subsequently, we utilized hierarchical regression analysis to examine the effects of the focal variables (CSR dimensions and price) on purchase intention. The baseline model was then expanded to incorporate potential moderators (e.g., motives for sustainable consumption, motives for purchasing cosmetics) and significant two-way interactions.

6. Theoretical Implications of the Findings

This study explored the influence of social and environmental corporate social responsibility (CSR) on consumer purchase intentions within the cosmetics market, revealing significant insights into the interplay between CSR dimensions, price sensitivity, and consumer motivations. The findings contribute to the growing body of literature on sustainable consumer behavior while offering actionable recommendations for businesses in fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) sectors.

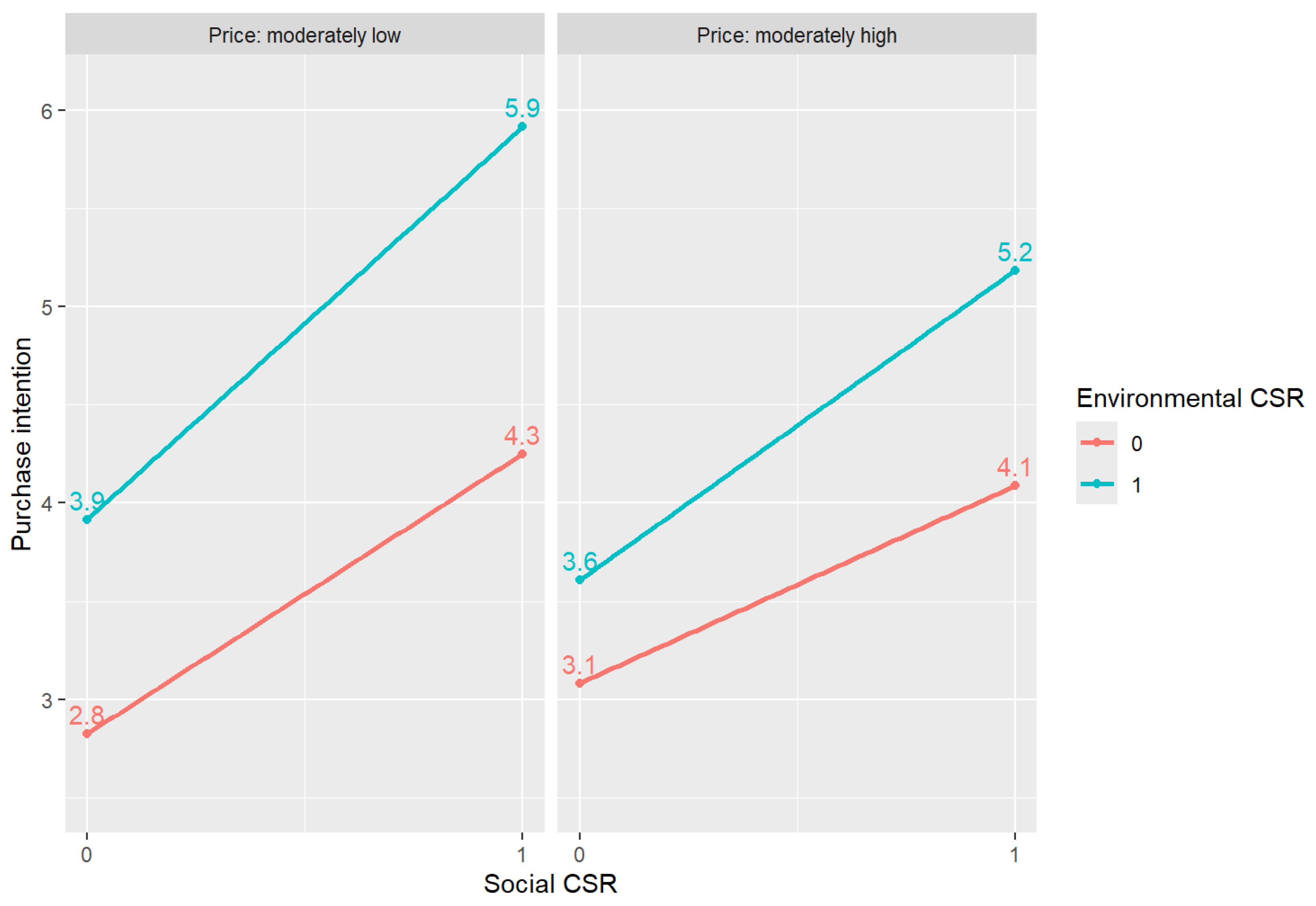

The results demonstrate that both social and environmental CSR positively influence purchase intentions, with their combined effect proving stronger than their individual contributions. This synergistic effect underscores the value of an integrated approach to CSR, where companies align both social and environmental efforts to maximize consumer engagement. This study also finds that price moderates the impact of environmental CSR, with higher prices diminishing its positive effect on purchase intentions. Intrinsic motivations enhance the influence of environmental CSR, partially offsetting its negative association at higher price points. Interestingly, hedonic and utilitarian motives did not significantly contribute to explaining purchase intentions in this context. Demographic differences, such as gender, also emerged, with women showing lower willingness to purchase compared to men under certain conditions.

These findings align with previous studies that emphasize the positive role of CSR in shaping consumer behavior. For example, Hojnik et al. [

16] found that strong environmental performance correlates with higher purchase intentions, echoing the current study’s results on the importance of environmental CSR. Similarly, Singh et al. [

15] highlighted the general effectiveness of CSR in enhancing brand recognition and purchase intentions, consistent with the observed positive effects of social CSR.

The current study’s distinct contribution is identifying the interaction between social and environmental CSR, which is a relatively underexplored area. While Pérez et al. [

38] and Behre and Cauberghe [

39] found diverging effects of these dimensions on social value and brand perceptions, this research demonstrates their complementary nature in amplifying purchase intentions. Moreover, the finding that intrinsic motives significantly moderate the effect of environmental CSR aligns with Wallach and Popovich’s [

18] argument that authenticity enhances CSR effectiveness. Conversely, the lack of significant effects from hedonic and utilitarian motives contrasts with Lin et al. [

46], suggesting context-specific variations in how consumer motivations interact with CSR.

This study also takes a more granular look than most previous research at the moderating role of price. While Liu and Xu [

29] observed a general diminishing effect of high prices on CSR’s impact, this study revealed a partial offsetting effect through intrinsic motivations, highlighting the importance of targeting consumers driven by personal values.

The complex role of intrinsic and extrinsic motives and the underlying psychological mechanisms in consumer decisions in our experiment warrants a more thorough elaboration. A negative main effect associated with intrinsic motives and a positive interaction between them and environmental CSR could be explained in two, not mutually exclusive, ways. Firstly, there could be a conflict between personal standards and product characteristics. Consumers with strong intrinsic motives often have high ethical and environmental standards. If they perceive the product or CSR initiatives as failing to meet these standards—such as incomplete environmental efforts or perceived greenwashing—they may reject the product, leading to lower purchase intentions. This aligns with prior research showing that skeptical consumers are more critical of CSR claims when they sense a mismatch between values and actions. On the other hand, the interaction effect suggests that when environmental CSR is robust and consistent with consumers’ values, it mitigates this skepticism and encourages purchase. For intrinsically motivated individuals, authentic and meaningful environmental CSR efforts seem to resonate strongly, turning initial hesitation into positive purchasing behavior. The transparency and credibility of CSR initiatives are critical in this process, as they bolster the perceived integrity of the brand.

Extrinsic motives, based on external rewards such as social status or peer approval, showed a non-significant relationship with purchase intentions in this study. This can be attributed to the lack of immediate tangible benefits from purchasing cosmetics from brands engaged in CSR. As such, while CSR may contribute to broader societal gains, it may not provide the social recognition or direct personal gain sought by extrinsically motivated individuals. Also, more generally, in the context of purchasing FMCG products like shampoo, extrinsic motives may have less relevance because these products are less visible to others and do not strongly contribute to social status. This contrasts with durable goods or luxury items, where extrinsic motives play a more prominent role in consumer decision making.

Overall, the results suggest that intrinsic motives are more relevant than extrinsic ones in driving purchase intentions for CSR-driven products in the cosmetics market. This is likely because purchasing decisions in this context are more personal and value-oriented, focusing on the alignment between the consumer’s ethical standards and the company’s practices.

The absence of a significant relationship between hedonic and utilitarian motives and purchase intentions in this study can be ascribed to the unique nature of CSR-driven purchasing decisions and the characteristics of the FMCG market, particularly the cosmetics industry.

Hedonic motives are linked to emotional pleasure, enjoyment, and experiential satisfaction. In the context of CSR-driven decisions, hedonic motives may be less relevant because CSR initiatives primarily appeal to values like ethics, responsibility, and sustainability. These values are more cognitive and less emotionally stimulating, especially when framed in practical terms like environmental sustainability or social contributions. As a result, CSR messaging may not evoke the same emotional appeal as factors like brand aesthetics or sensory product attributes, which are traditionally more aligned with hedonic motivations.

By contrast, utilitarian motives are associated with functional, rational decision-making, focusing on efficiency, utility, and value. In the cosmetics market, CSR attributes such as environmental or social responsibility may not be perceived as directly contributing to the product’s functional utility (e.g., cleansing, moisturizing). Instead, these attributes represent broader societal benefits that do not immediately satisfy the consumer’s functional needs. Consequently, utilitarian motivations are unlikely to drive CSR-related purchase intentions.

One possible explanation for why Hypothesis 6, which proposed that sustainable consumption moderates the relationship between CSR and purchase intentions, was not supported lies in the conceptual overlap between sustainable consumption and intrinsic motives. Both constructs emphasize personal values and ethical considerations, such as environmental consciousness and social responsibility, which may lead to a conflation of their effects. Consumers who engage in sustainable consumption often exhibit strong intrinsic motivations, such as a moral obligation to act sustainably or a desire for personal fulfillment through ethical choices. As a result, the moderating influence of sustainable consumption may already be accounted for by intrinsic motives in the model, rendering its independent effect statistically insignificant.

Moreover, sustainable consumption behaviors are typically habitual and deeply integrated into consumers’ lifestyles, potentially making them less responsive to external CSR cues. For instance, consumers who already prioritize sustainability in their daily lives may be less influenced by a company’s CSR initiatives, as these align with their existing values and behaviors. This could diminish the observable moderating effect of sustainable consumption in experimental settings.

7. Practical Recommendations

Our research suggests that companies should adopt a comprehensive approach to CSR that balances social and environmental dimensions. Because of the synergistic effects of these two dimensions, they reinforce each other to enhance consumer purchase intentions. Therefore, businesses should develop and communicate CSR initiatives that holistically address both social and environmental concerns, ensuring that they resonate with consumers on multiple levels.

In addition, targeting consumers with strong intrinsic motivations can yield significant benefits. Marketing efforts should focus on appealing to these consumers by emphasizing the authenticity, credibility, and genuine impact of the company’s CSR activities. For instance, brands can use storytelling to illustrate their commitment to sustainability, such as showcasing the tangible environmental benefits of their practices or highlighting specific community projects. Transparency and third-party certifications can further enhance trust and engagement among intrinsically motivated consumers.

Price sensitivity, a significant moderating factor, must also be addressed. While higher prices may dampen the positive effects of CSR, companies can mitigate this by communicating the value of their CSR initiatives. For example, brands can educate consumers about the additional costs of sustainable practices and the long-term benefits they bring to society and the environment. Offering tiered pricing or loyalty programs tied to CSR-driven products could also help bridge the gap for price-sensitive segments.

The findings also suggest that CSR strategies in the cosmetics market should consider demographic nuances, particularly gender differences. Women, who showed lower purchase intentions under certain conditions, may require targeted messaging that aligns CSR efforts with their specific concerns and preferences.

Finally, brands should recognize that hedonic and utilitarian motives may not naturally align with CSR-driven purchasing decisions. To bridge this gap, companies could frame their CSR efforts in ways that enhance emotional engagement and functional relevance. For example, emphasizing the luxurious feel of products made with sustainably sourced materials could appeal to hedonic motives, while highlighting the practical benefits of eco-friendly packaging, such as recyclability or safety, could address utilitarian considerations. By making CSR initiatives more relatable to these motives, companies can broaden their appeal to a wider consumer base.