Factors Affecting Former Fishers’ Satisfaction with Fishing Ban Policies: Evidence from Middle and Upper Reaches of Yangtze River

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methodology

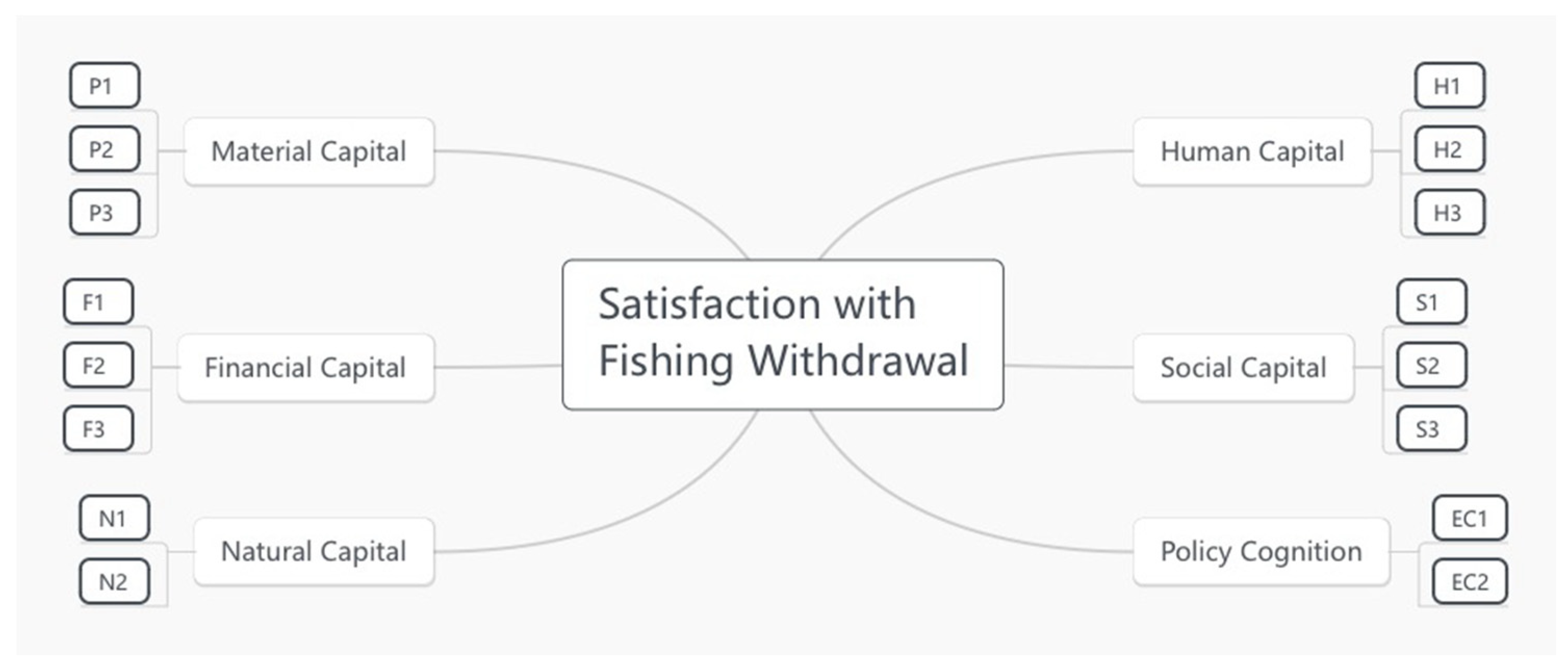

2.1. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

2.2. Research Design

2.2.1. Data Source

2.2.2. Descriptive Statistics of the Measurement Results of Satisfaction

2.2.3. Test of Questionnaire Data Reliability and Validity

3. Empirical Models and Results of Fishers’ Satisfaction with the Fishing Ban Policy

3.1. Empirical Models of Ordered Probit and the Structural Equation Model (SEM)

3.2. Results of Fishers’ Satisfaction with the Fishing Ban Policy

4. Discussion of Empirical Results

- (1)

- In this study, we assessed the influence of financial capital on fishers’ satisfaction with the fishing ban. In both Table 3 and Table 6, we can see that the path coefficient for the way that the hidden variables of financial capital influence fishers’ satisfaction with the fishing ban is maximal at 0.342. Among them, the household annual income, loan access, and insurance access had significant positive impacts on fishers’ satisfaction with the fishing ban at p < 0.01, p < 0.01, and p < 0.05, respectively. One-off cash compensation is among the government’s publicized ecological compensation policies, including compensation for the loss of fishing rights, compensation for the collection of fishing gear, and transitional living allowances. Compensation directly increases the income levels of fishers in the short term. The measures also include preferential micro-credit policies that aim to solve the financial constraints placed on fishers forced to change industries. To reduce some risks resulting from the fishing ban, some local governments have purchased insurance for the fishers. One thing is obvious: increasing the financial capital of fishers will enhance their satisfaction with the fishing ban policy [2,26].

- (2)

- The effect of the hidden variable of material capital on the satisfaction of fishers with the fishing ban is significant at a 1% level, with its path coefficient being 0.273. Simultaneously, the per capita residential area, durable household consumer goods, and transportation price have significant positive effects on fishers’ satisfaction with the policy at significance levels of p < 0.01, p < 0.05, and p < 0.05, respectively. The policy influencing fishers included professional fishers and part-time fishers. Some of the fishers have lived on their boats for a long time without having any housing on shore. Under the withdrawal policy, these fishers will return to live on the shore again. After landing, some fishers will surely purchase household necessities so that they can live in a town or county. Therefore, the housing area and durable household goods will have a major positive impact on satisfaction with the fishing ban policy. By directly improving the quality of life of a fisher’s family, material capital will make fishers more willing to actively accept the change in the fishing policy [1,8].

- (3)

- Considering human capital as a hidden variable, at the 1% level, it has a considerable effect on fishers’ satisfaction, with the path coefficient being 0.216. Two of the observable variables categorized as human capital—the education level of their family (at a level of 0.05) and the status of their family’s health (at a level of 0.01)—have significant positive correlations with fishers’ satisfaction. The higher the level of education, the more fishers can realize the importance of protecting the ecological environment and are likely to approve the establishment of the exit policy. The poorer the health status of relatives of fishers, the greater the living pressure, reducing satisfaction with the policy [6,23].

- (4)

- The hidden variable of social capital considers the influence that relationships with relatives and friends have on fishers’ satisfaction with the ban. The path coefficient is 0.108, with only getting along with relatives and friends having a significant positive impact on fishers’ satisfaction with the fishing ban (p < 0.05), indicating that fishers who get along with relatives and friends are more likely to accept the change brought on by the fishing ban [12,25].

- (5)

- Natural capital slightly affects the satisfaction of fishers. The possible reasons for this are as follows: most fishers are professional fishers who possess little arable land. According to the national policy of ‘keeping the land contract relationship stable and unchanged for a long time [30]’, fishers’ families cannot farm arable land if they withdraw from fishing. As ‘the state promotes the green development of the aquaculture industry’, fishers who withdraw from fishing find it difficult to transfer to natural water aquaculture; moreover, only a few fishers can provide aquaculture services in small fishponds. Thus, cultivated land area and aquaculture area do not have any statistically significant effects on the satisfaction of fishers [18].

- (6)

- Policy cognition’s relationship with the satisfaction of fishers who withdraw from fishing is significant at a 1% level, and the path coefficient is 0.187, as shown in Table 3. Besides policy cognition, the necessity of this policy has a significant influence on fishers’ satisfaction with the fishing ban, and the test level is p < 0.01. This can be explained by the fact that, before implementing the policy, the government first increased the publicity and explained the necessity of its implementation to fishers [10,24].

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

- (1)

- Amending legislation to protect the rights and interests of those fishers withdrawing from fishing: Fishers who withdraw from fishing are contributors to the protection of the Yangtze River. Further, in the ensuing Fishery Law, along with the Yangtze River Protection Law, retired fishers should receive legal assurance for their livelihoods. Protecting the aquatic ecology of the Yangtze River basin will then increase the satisfaction of the retired fishers.

- (2)

- The government should formulate policies that focus on the differences between fishers’ livelihood capacity and livelihood capital. For older fishers with lower livelihood capacity, the government should provide jobs that do not need high vocational skills to solve subsequent livelihood problems. For youth, vocational skills training should be provided to help them transfer into new jobs. For the self-employed fishers establishing small and micro-businesses, preferential policies such as discount loans and tax relief should be given. At the same time, the government should visit the fishers who change production methods and business models and organize community activities to allow them to integrate into their new living environment.

- (3)

- The government should provide insurance and improve social security. Most of the retired fishers are older and have a low level of education, and it is difficult for them to move into other industries after withdrawing from fishing. Rather than job training and support, the most important issues for these fishers are old-age security, medical care, and transitional-period life security policies. We recommend using compensation funds for the return of fishing and conversion of production and continuing to provide social security and medical insurance for older fishers; for local governments with difficulties supporting special groups, the government could help them to improve the procedures for handling subsistence allowances.

- (4)

- Increase publicity and social participation: Among the Yangtze River basin’s fishers, there is a lack of means to make a living after withdrawing from fishing; thus, many are likely to return to fishing. Moreover, poaching will likely increase in line with the recovery of fish stocks in the Yangtze River basin. The government should use all kinds of media to publicize the need and rationale for the fishing ban and change the optimism bias of some fishers. Meanwhile, social participation should be increased as much as possible. A fishery supervision and management process involving all aspects of society should be established.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, T.; Wang, Y.; Gardner, C.; Wu, F. Threats and Protection Policies of the Aquatic Biodiversity in the Yangtze River. J. Nat. Conserv. 2020, 58, 125931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Chen, T. Does the 10-Year Fishing Ban Compensation Policy in the Yangtze River Basin Improve the Livelihoods of Fishing Households? Evidence from Ma’anshan City, China. Agriculture 2022, 12, 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.S. The Reform of Watershed Ecological Compensation Mechanism from the Perspective of Life Community: A Case Study of the Minjiang Basin. Chin. Public Adm. 2019, 3, 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; China People’s University Press: Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Han, W.; Fu, Y.; Sun, W. Farmland Transfer Participation and Rural Well-Being Inequality: Evidence from Rural China with the Capability Approach. Land 2023, 12, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. The Study on Livelihood Capital Composition of Sea-Lost Fishermen: Based on Sustainable Livelihoods Framework of DFID. Chin. Fish. Econ. 2018, 36, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Blythe, J.L.; Cohen, P.J.; Eriksson, H.; Nash, K.L.; Cinner, J.E. Livelihoods and Fisheries Governance in a Contemporary Pacific Island Setting. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249654. [Google Scholar]

- Ou, M.; Zhong, Y.; Ma, H.; Wang, W.; Bi, M. Impacts of Policy-Driven Transformation in the Livelihoods of Fishermen on Agricultural Landscape Patterns: A Case Study of a Fishing Village, Island of Poyang Lake. Land 2022, 11, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.B.; Wang, C.; Samantha, P. Impact of Resettlement on Livelihood of Fishermen. Huazhong Agric. Univ. J. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2015, 5, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Zeng, F.S. Research on the Policy Cognition of Agricultural Support Protection Subsidies and Its Impact on Satisfaction—Based on the Survey of 419 Rice Farmers in Hunan Province. Rural Econ. 2019, 4, 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, M.; Brannlund, R. Factors Affecting Farmers’ Satisfaction with Agricultural Policies: Evidence from Rural Egypt. Agric. Econ. 2018, 49, 159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Y.; Wang, W.; Liu, J. Analysis of Farmers’ Satisfaction with Environmental Policies Using Ordered Probit Models: A Case Study in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 277, 111479. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.H. What Has China’s Nature Reserves Given to Surrounding Communities? Based on Survey Data of Farmers in Shaanxi, Sichuan, and Gansu from 1998 to 2014. Manag. World 2017, 3, 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Jin, L.S. Satisfaction of Rural Households on the Fallow Program and Its Influencing Factors in Groundwater Over-Exploited Areas in North China Plain. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2018, 32, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Li, M. Performance Appraisal Method for Rural Infrastructure Construction Based on Public Satisfaction. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239376. [Google Scholar]

- Tama, R.A.Z.; Hoque, M.M.; Liu, Y.; Alam, M.J.; Yu, M. An Application of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to Examining Farmers’ Behavioral Attitude and Intention towards Conservation Agriculture in Bangladesh. Agriculture 2023, 13, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WorldFish. Lived Experiences: Small-Scale Fishers and Fishworkers Share Their Stories. WorldFish. 2021. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12348/4456 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Chambers, R.; Conway, G. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical Concepts for the 21st Century; Institute of Development Studies: Falmer, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Atmış, E.; Özden, S.; Lise, W. Public Participation in Forestry in Turkey. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 62, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defrancesco, E.; Gatto, P.; Runge, F.; Trestini, S. Factors Affecting Farmers’ Participation in Agri-Environmental Measures: A Northern Italian Perspective. J. Agric. Econ. 2008, 59, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.G.; Chen, X.N. Livelihood Capitals and the Migration Satisfaction of Rural Households: A Case in Southern Shaanxi Province. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2018, 32, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.; Cai, Y.Y. Dynamic Response Relation between Farmers’ Livelihood Assets and Farmland Protection Compensation Policy Effects. China Land Sci. 2017, 31, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Han, F.; Zhu, L.Z. Satisfaction Analysis of Herdsmen Based on Grassland Ecological Construction: A Case Study of Gannan Grassland. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2017, 3, 120–128. [Google Scholar]

- Hounsome, B.; Edwards, R.T.; Edwards-Jones, G. A Note on the Effect of Farmer Mental Health on Adoption: The Case of Agri-Environment Schemes. Agric. Syst. 2006, 91, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yang, L.; Bai, Y.; Wang, X. The Impacts of Farmers’ Livelihood Endowments on Their Participation in Eco-Compensation Policies: Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems Case Studies from China. Land Use Policy 2018, 77, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Zhang, G.Q.; Huo, X.X. The Effect of Ecological Compensation, Livelihood Capital on Residents’ Sustainable Livelihoods Ability: The Case of the Shaanxi National Key Ecological Function Areas. Econ. Geogr. 2017, 37, 188–196. [Google Scholar]

- Vinzi, V.E.; Trinchera, L.; Amato, S. PLS Path Modeling: From Foundations to Recent Developments and Open Issues for Model Assessment and Improvement. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 47–82. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, K.K.K. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Techniques Using SmartPLS. Mark. Bull. 2013, 24, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D. A Practical Guide to Factorial Validity Using PLS-Graph: Tutorial and Annotated Example. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2005, 16, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Opinions on Strengthening the Protection of Aquatic Life in the Yangtze River. Gazette of the State Council, 2019, (Issue 34). Available online: https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2019/content_5459130.htm (accessed on 23 January 2025).

| Variable | Variable Meaning and Assignment | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Physical capital (P) | |||

| Per capita residential area (P1) | The ratio of house size (square meters) to family size: P1 ≤ 10 (1); 10 < P1 ≤ 20 (2); 20 < P1 ≤ 30 (3); 30 < P1 ≤ 40 (4); P1 ≥ 40 (5) | 3.120 | 1.088 |

| Types of durable household goods (P2) | Types of durable goods owned: P2 = 0 (1); P2 = 1–2 (2); P2 = 3–4 (3); P2 = 5–6 (4); P2 ≥ 7 (5) | 3.260 | 0.925 |

| Transportation price (P3) (CNY) | Total purchase price of vehicles (cars, motorcycles, electric vehicles, etc.): P3 ≤ 10,000 (1); 10,000 < P3 ≤ 30,000 (2); 30,000 < P3 ≤ 50,000 (3); 50,000 < P3 ≤ 80,000 (4); P3 ≥ 80,000 (5) | 2.930 | 1.047 |

| 2. Human capital (H) | |||

| Family education level (H1) | Uneducated (1); primary school (2); junior high school (3); high school (4); college degree or above (5) | 2.740 | 1.035 |

| Labor force (H2) | H2 = 0 (1); H2 = 1–2 (2); H2 = 3–4 (3); H2 = 5–6 (4); H2 ≥ 7 (5) | 3.060 | 1.150 |

| Family health (H3) | Long-term illness (1); frequent illness (2); occasional illness (3); rarely get sick (4); not sick (5) | 3.440 | 1.176 |

| 3. Financial capital (F) | |||

| Annual household income (F1) (CNY) | F1 ≤ 10,000 (1); 10,000 < F1 ≤ 30,000 (2); 30,000 < F1 ≤ 50,000 (3); 50,000 < F1 ≤ 80,000 (4); F1 ≥ 80,000 (5) | 2.990 | 1.119 |

| Loan situation (F2) | Is it easy to obtain a loan: Very difficult (1); difficult (2); average (3); easy (4); very easy (5) | 3.040 | 1.032 |

| Insurance (F3) | Types of health insurance and pension insurance: F3 = 0 (1); F3 = 1 type (2.5); F3 = 2 types (5) | 2.660 | 1.341 |

| 4. Social capital (S) | |||

| Relationships with relatives and friends (S1) | Contact time with relatives and friends: Barely (1); low (2); average (3); much (4); high (5) | 3.180 | 0.951 |

| Relationships with village cadres (S2) | Contact times with village cadres: Barely (1); low (2); average (3); much (4); high (15) | 3.070 | 0.936 |

| Number of times of participation in village (community) activities (S3) | S3 = 0 (1); S3 = 1–2 (2); S3 = 3–4 (3); S3 = 5–6 (4); S3 ≥ 7 (5) | 2.710 | 1.046 |

| 5. Natural capital (N) | |||

| Cultivated area (N1) (mu) (1 ha = 15 mu) | N1 = 0 (1); 0 < N1 ≤ 1 (2); 1 < N1 ≤ 3 (3); 3 < N1 ≤ 5 (4); N1 ≥ 5 (5) | 2.110 | 1.080 |

| Aquaculture area (N2) (mu) (1 ha = 15 mu) | N2 = 0 (1); 0 < N2 ≤ 1 (2); 1 < N2 ≤ 3 (3); 3 < N2 ≤ 5 (4); N2 ≥ 5 (5) | 1.210 | 0.716 |

| 6. Policy cognition (EC) | |||

| Knowledge of the policy (EC1) | Very little understanding (1); do not know much about it (2); general understanding (3); good understanding (4); understand it very well (5) | 3.110 | 1.059 |

| The necessity of policy implementation (EC2) | Very unnecessary (1); unnecessary (2); neutral (3); necessary (4); very necessary (5) | 3.400 | 0.997 |

| Satisfaction | Very Dissatisfied (1) | Dissatisfied (2) | General (3) | Satisfied (4) | Very Satisfied (5) | Mean | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample | 8 (4.47%) | 40 (22.35%) | 64 (35.75%) | 51 (28.49%) | 16 (8.94%) | 3.15 | 179 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Standard Error | Z Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Per capita residential area, P1 | 0.515 *** | 0.158 | 3.260 |

| Durable household goods, Category P2 | 0.465 ** | 0.188 | 2.470 |

| Transportation price, P3 | 0.338 ** | 0.158 | 2.140 |

| Family education level, H1 | 0.403 ** | 0.177 | 2.280 |

| Labor force number, H2 | 0.121 | 0.159 | 0.760 |

| Family health status, H3 | 0.447 *** | 0.135 | 3.310 |

| Annual household income, F1 | 0.501 *** | 0.151 | 3.320 |

| Credit situation, F2 | 0.712 *** | 0.176 | 4.060 |

| Insurance, F3 | 0.350 ** | 0.147 | 2.390 |

| Relationships with relatives and friends, S1 | 0.484 ** | 0.199 | 2.430 |

| Relationships with village cadres, S2 | −0.151 | 0.192 | −0.790 |

| Number of activities organized in the village, S3 | 0.101 | 0.167 | 0.610 |

| Cultivated land area, N1 | −0.035 | 0.123 | −0.290 |

| Culture area, N2 | −0.121 | 0.172 | −0.710 |

| Policy understanding, EC1 | 0.258 | 0.165 | 1.560 |

| Necessary degree of policy implementation, EC2 | 0.833 *** | 0.206 | 4.040 |

| LR chi2 (16) | 379.970 | ||

| Prob > chi2 | 0.000 | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.750 | ||

| F | H | P | S | EC | y | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 0.84 | 0.437 | 0.536 | 0.397 | 0.49 | 0.664 |

| F2 | 0.795 | 0.516 | 0.57 | 0.444 | 0.528 | 0.702 |

| F3 | 0.701 | 0.445 | 0.389 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.538 |

| H1 | 0.607 | 0.871 | 0.623 | 0.523 | 0.478 | 0.697 |

| H3 | 0.373 | 0.801 | 0.488 | 0.486 | 0.358 | 0.571 |

| P1 | 0.424 | 0.543 | 0.724 | 0.462 | 0.453 | 0.606 |

| P2 | 0.521 | 0.434 | 0.707 | 0.4 | 0.564 | 0.594 |

| P3 | 0.492 | 0.511 | 0.788 | 0.56 | 0.44 | 0.645 |

| S1 | 0.547 | 0.603 | 0.643 | 1 | 0.496 | 0.694 |

| EC2 | 0.603 | 0.505 | 0.653 | 0.496 | 1 | 0.734 |

| Y | 0.819 | 0.763 | 0.83 | 0.694 | 0.734 | 1 |

| Mean | S.D. | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | 0.342 | 0.042 | 0.823 | 0.610 |

| H | 0.219 | 0.053 | 0.823 | 0.700 |

| P | 0.274 | 0.053 | 0.784 | 0.549 |

| S | 0.105 | 0.039 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| EC | 0.184 | 0.042 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Path | Influence Direction | Path Coefficient | Distinctiveness | Test Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial capital → Withdrawal satisfaction | + | 0.342 *** | 0.000 | Support H1 |

| Human capital → Withdrawal satisfaction | + | 0.216 *** | 0.000 | Support H2 |

| Material capital → Withdrawal satisfaction | + | 0.273 *** | 0.000 | Support H3 |

| Social capital → Withdrawal satisfaction | + | 0.108 *** | 0.005 | Support H4 |

| Policy cognition → Withdrawal satisfaction | + | 0.187 *** | 0.000 | Support H6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, K.; Xu, M.; Chen, T.; Wang, Y. Factors Affecting Former Fishers’ Satisfaction with Fishing Ban Policies: Evidence from Middle and Upper Reaches of Yangtze River. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2045. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052045

Liu K, Xu M, Chen T, Wang Y. Factors Affecting Former Fishers’ Satisfaction with Fishing Ban Policies: Evidence from Middle and Upper Reaches of Yangtze River. Sustainability. 2025; 17(5):2045. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052045

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Kun, Minghao Xu, Tinggui Chen, and Yan Wang. 2025. "Factors Affecting Former Fishers’ Satisfaction with Fishing Ban Policies: Evidence from Middle and Upper Reaches of Yangtze River" Sustainability 17, no. 5: 2045. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052045

APA StyleLiu, K., Xu, M., Chen, T., & Wang, Y. (2025). Factors Affecting Former Fishers’ Satisfaction with Fishing Ban Policies: Evidence from Middle and Upper Reaches of Yangtze River. Sustainability, 17(5), 2045. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052045