The Role of Social Financing in Promoting Social Equity and Shared Value: A Cross-Sectional Study of Small and Medium Enterprises in Malaysia and Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothetical Development

2.1. Islamic Endowment’s (waqf) Role

2.2. Business Obstacles

2.3. Access to Finance

2.4. Globalization Impact

2.5. Government Support

2.6. Financial Institutions

2.7. Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Theory

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measurement of Variables

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Profile of the Respondents

4.2. Descriptive Analysis

4.3. Reliability and Validity

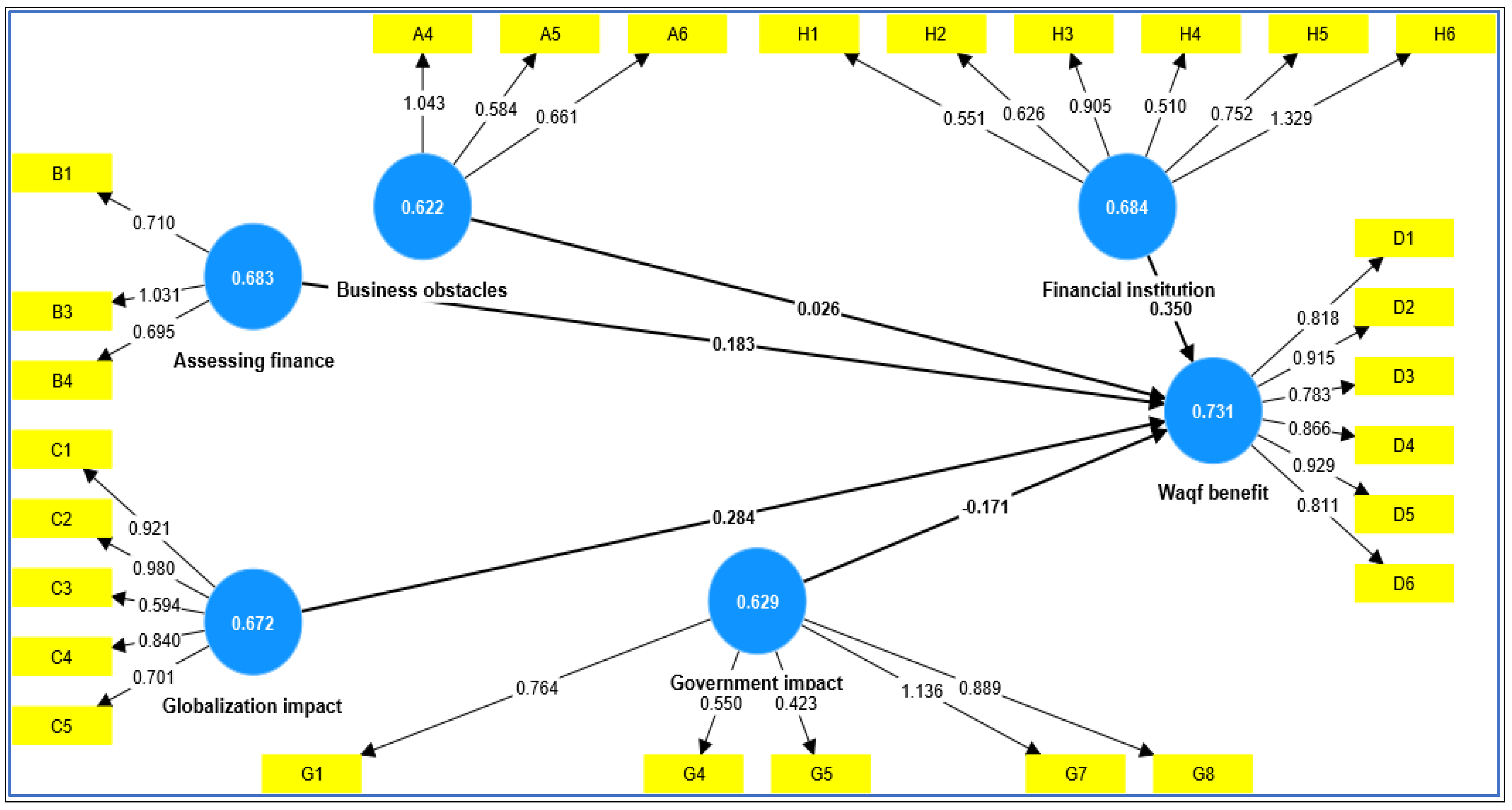

4.4. Measurement Model

4.5. Convergent Validity

4.6. Discriminant Validity

4.7. Structural Model

5. Discussion

6. Theoretical and Practical Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mikail, S.I.; Djafri, F.; Ahmad, M. Waqf and Microfinance Integration for Enabling Sustainable Financial Inclusion: Analysis of Sharī‘ah Compliance. Int. J. Islam. Financ. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 16, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascarya, A.; Sukmana, R.; Rahmawati, S.; Masrifah, A. Developing cash waqf models for baitul maal wat tamwil as integrated islamic social and commercial microfinance. J. Islam. Account. Bus. Res. 2022, 14, 699–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaker, M.A.; Thaker, H.B.; Pitchay, A.B.; Amin, M.F.; Khaliq, A.B. Leveraging Islamic Banking and Finance for Small Businesses: Exploring the Conceptual and Practical Dimensions; Asian Development Bank Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Abdeldayem, M.; Aldulaimi, S. Entrepreneurial finance and crowdfunding in the Middle East. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2023, 31, 927–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarubahrina, A.F.; Ayedh, A.M.A.; Khairi, K.F. Accountability practices of Waqf institution in selected states in Malaysia: A critical analysis. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Account. 2019, 27, 331–352. [Google Scholar]

- Alabdulwahab, S. The linkage between oil and non-oil GDP in Saudi Arabia. Economies 2021, 9, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsha’at. SME Monitor Monsha’at Quarterly Report Q4 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.monshaat.gov.sa/sites/default/files/2024-02/SME%20Monitor%20-%20Q4%202023%20EN_0.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2023).

- Department of Statistics Malaysia. 28 July 2021; Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) Performance 2020. Available online: https://www.dosm.gov.my/portal-main/release-content/small-and-medium-enterprises-smes-performance-2020 (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Laila, N.; Ratnasari, R.T.; Ismail, S.; Mahphoth, M.H.; Hidzir, P.A. Awareness Towards Waqf Entrepreneurship In Malaysia and Indonesia: An Empirical Investigation. Al-Shajarah 2022, 27, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Vision 2030. 2016. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/media/rc0b5oy1/saudi_vision203.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- World Bank SME Finance. 2021. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/smefinance (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Fouejieu, A.; Ndoye, A.; Sydorenko, T. Unlocking access to finance for SMEs. IMF Work. Pap. 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, L.; Arcuri, M.C.; Ielasi, F. How does government-backed finance affect SMEs’ crisis predictors? Small Bus. Econ. 2023, 61, 1205–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulghaffar, N.; Akkad, G. Internal and external barriers to entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia. Dig. Middle East Stud. 2021, 30, 116–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saci, K.; Mansour, W. Risk Sharing, SMEs’ Financial Strategy, and Lending Guarantee Technology. Risks 2023, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.; Li, Y.; Vigne, S.A.; Wu, Y. Why do small businesses have difficulty in accessing bank financing? Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 84, 102352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, N.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. The Role of SMEs in Asia and Their Difficulties in Assessing Finance; ADBI Working Paper Series; Asian Development Bank Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. OECD Economic Outlook, Interim Report March 2022: Economic and Social Impacts and Policy Implications of the War in Ukraine. OECD. 2022. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/4181d61b-en/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/4181d61b-en#figure-d1e260 (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Yusgiantoro, I.; Pamungkas, P.; Trinugroho, I. The sustainability and performance of Bank Wakaf Mikro: Waqf-based microfinance in Indonesia. Int. J. Islam. Middle East. Financ. Manag. 2024, 17, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muslimin, J.; Qamar, B.; Sen, H. Waqf, sharia venture capital, and institutional problems: Socio-legal cases in Indonesia. Akad. J. Pemikir. Islam 2022, 27, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukmana, R. Critical assessment of Islamic endowment funds (Waqf) literature: Lesson for government and future directions. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, A.Y.; Mohammed, M.O.; Al-Jubari, I.; Ahamed, F. The prospect of waqf in financing small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in yemen. QIJIS (Qudus Int. J. Islam. Stud.) 2022, 10, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haniff, W.A.; Markom, R.; Zainoddin, W.M. Optimising under-utilised waqf assets in malaysia through social entrepreneurship. Int. J. Asian Soc. Sci. 2023, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.A.; Ismail, A.G.; Shafiai, M.H. Application of waqf for social and development finance. Int. J. Islam. Financ. 2017, 9, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salleh, N.; Kassim, S.; Muhammad, N.M.; Yusoff, S.S.; Mahadi, N.F.; Ariffin, K.M. Application of blockchain technology in the management of waqf institutions: Concepts, challenges and recommendations. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Computing (ICOCO), Langkawi Island, Malaysia, 9–12 October 2023; pp. 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, R.; Hassan, M.K.; Rashid, M. The Role of Waqf in Educational Development–Evidence from Malaysia. J. Islam. Financ. 2018, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, G.K.; Rani, A.O. Market-Based Financing for SMEs in Malaysia: Issues, Challenges, and Way Forward. Institute of Capital Market Research Malaysia. 2024. Available online: https://www.icmr.my/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/ICMR_SME-Financing-Report_FINAL_23022024.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Khan, M.A. Barriers constraining the growth of and potential solutions for emerging entrepreneurial SMEs. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2022, 16, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, J.; Mahmood, S.; Scott, J. Gender, microcredit and poverty alleviation in a developing country: The case of women entrepreneurs in pakistan. J. Int. Dev. 2018, 31, 247–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, K.; Md, A. Awareness of Donors Towards the Use of Cash Waqf Financing for Microenterprises in Malaysia; I-Maf E-Proceedings; Masjid Al-Azhar Kolej Universiti Islam Antarabangsa: Kajang, Malaysia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zherlitsyn, D.; Levytskyi, S.; Mykhailyk, D.; Ogloblina, V. Assessment of Financial Potential as a Determinant of Enterprise Development. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Strategies, Models and Technologies of Economic Systems Management (SMTESM 2019), Khmelnytskyi, Ukraine, 4–6 October 2019; Atlantis Press: Khmelnytskyi, Ukraine, 2019; pp. 212–216. [Google Scholar]

- Ramzi, M.I.; Mohamad, W.M.; Ridzwan, R. Financial Management Practices: Challenges for SMEs in Malaysia. Int. J. Acad. Res. Account. Financ. Manag. Sci. 2022, 12, 666–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, N.; Che-Aini, A.I. The potential of waqf-based microfinance in financing small and medium enterprises (SMEs): An overview. Int. J. Islam. Middle East. Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 38–54. [Google Scholar]

- Uula, M. Productivity of waqf funds in indonesia. Int. J. Waqf 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lousada, S.A.; Tabau, C.; Leite, E.; Carvalho, A. The Douro Demarcated Region: The Relevance of Tourism in the Internationalization Strategies of Companies. In Handbook of Research on Sustainable Development Goals, Climate Change, and Digitalization; Castanho, R.A., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; p. 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krambia-Kapardis, M.; Stavrou, E.T. Entrepreneurial decision-making in an era of globalization: The role of country-level institutional quality and cultural distance. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 130, 242–253. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D.C.; Cuervo-Cazurra, A. Understanding the Effects of Globalization on Firm Performance. J. Manag. 2020, 46, 333–355. [Google Scholar]

- Erumban, A.A.; Koo, J. Globalization and the Productivity of Small and Medium Enterprises. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 57, 1013–1033. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Basset, M.; Mohamed, R.; Jiang, X. A Framework for Sustainable Supply Chain Collaboration in the Era of Globalisation for Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126–134. [Google Scholar]

- Shamsuddin, S.; Rahman, A.R. The Impact of Globalisation on SMEs in Malaysia. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Government Support in Industrial Sectors: A Synthesis Report. Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. 2023. Available online: https://one.oecd.org/document/TAD/TC(2022)8/FINAL/en/pdf (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Aziz, A.A.; Omar, M.A.; Sori, Z.M. The potential of waqf financing in promoting small and medium enterprises in Malaysia. Int. J. Islam. Bus. Econ. Aff. 2021, 22–34. [Google Scholar]

- Riani, R.; Fatoni, A. Waqf on infrastructure: How far has been researched? Int. J. Waqf 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapsari, I.; Novandari, W.; Sunarko, B.; Oetomo, H.; Inayati, N. The effect of international entrepreneurship orientation and network capability on smes international performance; The important role of goverment support. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Business, Accounting, and Economics, ICBAE 2022, Purwokerto, Indonesia, 10–11 August 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soemitra, A.; Kusmilawaty; Rahma, T.I. The Role of Micro Waqf Bank in Women’s Micro-Business Empowerment through Islamic Social Finance: Mixed-Method Evidence from Mawaridussalam Indonesia. Economies 2022, 10, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tony, M. The role of financial institutions in promoting entrepreneurship and economic growth. J. Bus. Leadersh. Manag. 2023, 1, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V.; Jones, P. COVID-19 and Entrepreneurship Education: Implications for Advancing Research and Practice. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.A.; Kabil, M.; Alayan, R.; Magda, R.; Dávid, L.D. Entrepreneurship ecosystem performance in Egypt: An empirical study based on the Global Entrepreneurship Index (GEI). Sustainability 2021, 13, 7171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikmund, W.G. Business Research Methods, 7th ed.; Thomson/South-Western: Mason, OH, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sekaran, U. Research Methods for Business: A Skill-Building Approach, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Easterby-Smith, M. Disciplines of organizational learning: Contributions and critiques. Hum. Relat. 1997, 50, 1085–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F.; Berbekova, A.; Assaf, A.G. Understanding and managing the threat3of common method bias: Detection, prevention and control. Tour. Manag. 2021, 86, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Shukor, S.; Anwar, I.F.; Abdul Aziz, S.; Sabri, H. Muslim attitude towards participation in cash WAQF: Antecedents and consequences. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2017, 18, 193–204. [Google Scholar]

- Soomro, B.A.; Abdelwahed, N.A.A.; Shah, N. The Influence of Demographic Factors on the Business Success of Entrepreneurs: An Empirical Study from the Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Context of Pakistan. Int. J. Entrep. 2019, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley, T.F.; Henriksen, E.; Nusbaum, C. Demographic Obstacles to European Growth; NBER Working Paper No. 26503; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasiuzzaman, S.; Nurdin, N.; Abdullah, A.H.; Vinayan, G. Creditworthiness and access to finance: A study of SMEs in the Malaysian manufacturing industry. Manag. Res. Rev. 2019, 43, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, M.; Liu, J.; Ren, W. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on micro, small, and medium-sized Enterprises operating in Pakistan. Res. Glob. 2020, 2, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidzir, P.A.M.; Ismail, S.; Kassim, E.S. Government Support, Stakeholder Engagement and Social Entrepreneurship Performance: An Exploratory Factor Analysis. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2021, 11, 1604–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghion, P.; Fally, T.; Scarpetta, S. Credit constraints as a barrier to the entry and post-entry growth of firms. Econ. Policy 2007, 22, 732–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramayah TJ, F.H.; Cheah, J.; Chuah, F.; Ting, H.; Memon, M.A. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using smartPLS 3.0: An Updated Guide and Practical Guide to Statistical Analysis; Pearson: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2018; pp. 967–978. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A.; Malhotra, A.; Segars, A. Knowledge Management: An Organizational Capabilities Perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G. Lateral collinearity and Misleading Results in Variance-Based SEM: An Illustration and Recommendations. 26 September 2012. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2152644 (accessed on 29 November 2023).

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Nazaruddin, N.M.; Ahmad, N.A. Waqf investment as a means of financing small and medium-sized enterprises: A review. Int. J. Islam. Middle East. Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 317–333. [Google Scholar]

- Alshebami, A.S. Survivingthe Storm: The Vital Role of Entrepreneurs’ Network Ties andRecovering Capabilities in Supportingthe Intention to Sustain Micro andSmall Enterprises. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Financing Method | Waqf | Loans | Incentives (Grant/Subsidies) | Crowdfunding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nature | Charitable, no repayment required. | Debt-based, requires repayment plus interest. | Financial support by the government or private entities, often non repayable. | Collective fundraising from public or investors. |

| Key advantages | Interest-free, aligns with Islamic principles, promotes social welfare. | Widely available, structured, and flexible. | Non-repayable funds to promote business growth. | No debt incurred, access to a broad funding base. |

| Key disadvantages | Limited scope, traditionally focused on religious/charitable projects. | Requires repayment with interest (or profit), collateral often needed. | Limited availability, highly competitive, dependent on government policies. | Uncertain success, requires strong marketing and appeal. |

| Scope of Use | Community development and social welfare. | Flexible, can be used for various business purposes such as expansion, working capital. | Specific to government objectives such as innovation, R&D, job creation. | Suitable for startups, creative projects, and new products. |

| Examples | Yayasan Waqaf Malaysia and General Authority for Awqaf Saudi Arabia. | SME Bank Malaysia and SME Bank Saudi Arabia. | SME Corp Malaysia’s Matching Grant and Saudi Vision 2030 SME Support Program. | Funding Society and Lendo. |

| Constructs and Sources of Developed Measures | Items | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Business Obstacles [56,57] | Gender is an obstacle in my business | 2.25 | 1.847 |

| Age is an obstacle in my business | 2.32 | 1.792 | |

| Education background is an obstacle in my business | 2.51 | 1.873 | |

| Lack of experience is an obstacle in my business | 3.61 | 2.180 | |

| Availability of capital is an obstacle in my business | 4.24 | 2.308 | |

| Lack of training is an obstacle in my business | 3.48 | 2.192 | |

| Lack of expertise is an obstacle in my business | 3.14 | 2.162 | |

| Access to finance [58] | My company lacks a credit record | 2.85 | 1.891 |

| My company is inadequate in business planning | 2.46 | 1.663 | |

| My company does not meet financial institutions’ requirements | 2.92 | 1.891 | |

| My company is poor in business performance | 2.56 | 1.685 | |

| Globalization Impact [59] | My company is facing difficulty in coping with the recession | 3.96 | 1.897 |

| My company is facing barriers posed by global sourcing | 3.79 | 1.881 | |

| My company is facing low productivity | 3.52 | 1.801 | |

| My company is facing a lack of organizational expertise | 3.65 | 1.867 | |

| My company is facing a lack of funding | 3.93 | 1.973 | |

| My company is facing a lack of access to technology | 3.25 | 1.847 | |

| Government Support [60] | Government agencies offer me waqf | 1.76 | 1.438 |

| I am getting training provided by the government agencies for improving my business | 2.97 | 2.026 | |

| I am obtaining financial facilities for my business from the government agencies | 2.43 | 1.892 | |

| I am getting free land for my business from the government agencies | 1.66 | 1.524 | |

| My company is moving toward technological knowledge with the help of the government | 2.27 | 1.829 | |

| The government provides programs for entrepreneurship to me as a young Saudi/Malaysian | 3.63 | 2.166 | |

| The government agencies support my halal business start-ups fundraising through waqf | 2.19 | 1.967 | |

| The government boosting digitalization and advanced technology through the waqf fund for my business | 2.40 | 2.050 | |

| Financial Institution [46,61] | Financial institutions (FI) provide funding as start-up capital for my business | 3.29 | 2.230 |

| FI provides flexible loan repayment for my business | 3.31 | 2.171 | |

| FI provides enough finances (funds) to channel for SMEs | 3.56 | 2.103 | |

| FI provides access to credit facilities for my business | 3.56 | 2.183 | |

| FI provides Islamic products to my business | 3.67 | 2.203 | |

| FI should collaborate with the government for waqf development for SMEs | 4.68 | 2.012 | |

| FI provides a micro-funding source to develop new businesses for SMEs | 4.49 | 2.085 | |

| Role of Waqf [55] | To fund poverty alleviation programs | 5.29 | 1.922 |

| To fund medical benefits | 5.08 | 2.043 | |

| To fund entrepreneur development | 5.37 | 1.978 | |

| To feed families through many economic empowerment initiatives | 5.34 | 1.999 | |

| Cash waqf funds able to be supplemental governmental revenues | 5.00 | 2.079 | |

| Waqf can help in controlling unsustainable debt as waqf to finance public expenditures or at least part of it | 5.26 | 1.982 |

| Construct | Items | Loading | AVE | CR | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islamic endowment (waqf)’s role | D1 | 0.842 | 0.776 | 0.945 | 0.942 |

| D2 | 0.927 | ||||

| D3 | 0.880 | ||||

| D4 | 0.882 | ||||

| D5 | 0.885 | ||||

| D6 | 0.867 | ||||

| Business obstacles | A4 | 0.911 | 0.717 | 0.903 | 0.809 |

| A5 | 0.787 | ||||

| A6 | 0.837 | ||||

| Access to finances | B1 | 0.885 | 0.770 | 0.906 | 0.851 |

| B3 | 0.934 | ||||

| B4 | 0.808 | ||||

| Globalization impact | C1 | 0.883 | 0.743 | 0.930 | 0.914 |

| C2 | 0.883 | ||||

| C3 | 0.892 | ||||

| C4 | 0.851 | ||||

| C5 | 0.798 | ||||

| Government support | G1 | 0.813 | 0.695 | 0.962 | 0.893 |

| G4 | 0.860 | ||||

| G5 | 0.681 | ||||

| G7 | 0.936 | ||||

| G8 | 0.858 | ||||

| Financial institutions | H2 | 0.842 | 0.775 | 1.019 | 0.945 |

| H3 | 0.899 | ||||

| H4 | 0.926 | ||||

| H5 | 0.921 | ||||

| H6 | 0.886 | ||||

| H7 | 0.803 |

| Access to Finances | Business Obstacles | Financial Institutions | Globalization Impact | Government Support | Islamic Endowment (waqf)’s Role | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access to finances | 0.877 | |||||

| Business obstacles | 0.131 | 0.847 | ||||

| Financial institutions | −0.301 | 0.071 | 0.881 | |||

| Globalization impact | 0.379 | 0.351 | 0.092 | 0.862 | ||

| Government support | −0.101 | 0.104 | 0.219 | −0.250 | 0.834 | |

| Islamic endowment (waqf)’s role | 0.197 | 0.155 | 0.278 | 0.419 | −0.177 | 0.881 |

| Access to Finances | Business Obstacles | Financial Institutions | Globalization Impact | Government Support | Islamic Endowment (waqf)’s Role | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access to finances | ||||||

| Business obstacles | 0.203 | |||||

| Financial institutions | 0.338 | 0.098 | ||||

| Globalization impact | 0.445 | 0.410 | 0.104 | |||

| Government support | 0.120 | 0.135 | 0.260 | 0.253 | ||

| Islamic endowment (waqf)’s role | 0.214 | 0.176 | 0.256 | 0.436 | 0.177 |

| Hs. | Path Relationship | Std. Beta | t-Values | p-Values | F2 | R2 | VIF | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Business obstacles -> Islamic endowment (waqf)’s role | 0.104 | 0.302 | 0.763 | 0.001 | 0.277 | 1.223 | Rejected |

| H2 | Access to finance -> Islamic endowment (waqf)’s role | 0.090 | 1.966 | 0.049 | 0.032 | 1.426 | Accepted | |

| H3 | Globalization impact -> Islamic endowment (waqf)’s role | 0.092 | 2.901 | 0.004 | 0.064 | 1.608 | Accepted | |

| H4 | Government support -> Islamic endowment (waqf)’s role | 0.105 | 1.615 | 0.106 | 0.033 | 1.194 | Rejected | |

| H5 | Financial institutions -> Islamic endowment (waqf)’s role | 0.087 | 3.952 | 0.000 | 0.129 | 1.249 | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarabdeen, M.; Ismail, S.; Mohd Hidzir, P.A.; Alofaysan, H.; Rahmat, S. The Role of Social Financing in Promoting Social Equity and Shared Value: A Cross-Sectional Study of Small and Medium Enterprises in Malaysia and Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1889. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051889

Sarabdeen M, Ismail S, Mohd Hidzir PA, Alofaysan H, Rahmat S. The Role of Social Financing in Promoting Social Equity and Shared Value: A Cross-Sectional Study of Small and Medium Enterprises in Malaysia and Saudi Arabia. Sustainability. 2025; 17(5):1889. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051889

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarabdeen, Masahina, Shafinar Ismail, Putri Aliah Mohd Hidzir, Hind Alofaysan, and Suharni Rahmat. 2025. "The Role of Social Financing in Promoting Social Equity and Shared Value: A Cross-Sectional Study of Small and Medium Enterprises in Malaysia and Saudi Arabia" Sustainability 17, no. 5: 1889. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051889

APA StyleSarabdeen, M., Ismail, S., Mohd Hidzir, P. A., Alofaysan, H., & Rahmat, S. (2025). The Role of Social Financing in Promoting Social Equity and Shared Value: A Cross-Sectional Study of Small and Medium Enterprises in Malaysia and Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 17(5), 1889. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051889