Emotional Support as a Lifeline: Promoting the Sustainability of Quality of Life for College Students with Disabilities Facing Mental Health Disorders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Framework and Hypothesis Building

2.1. MH and QoL Among Students with Disabilities

2.2. The Moderating Role of Emotional Support

3. Methods

3.1. Study Measures

3.2. Data Collection and Sampling

4. Data Analysis Technique

5. Results

5.1. Assessing Endogeneity in the Research Model

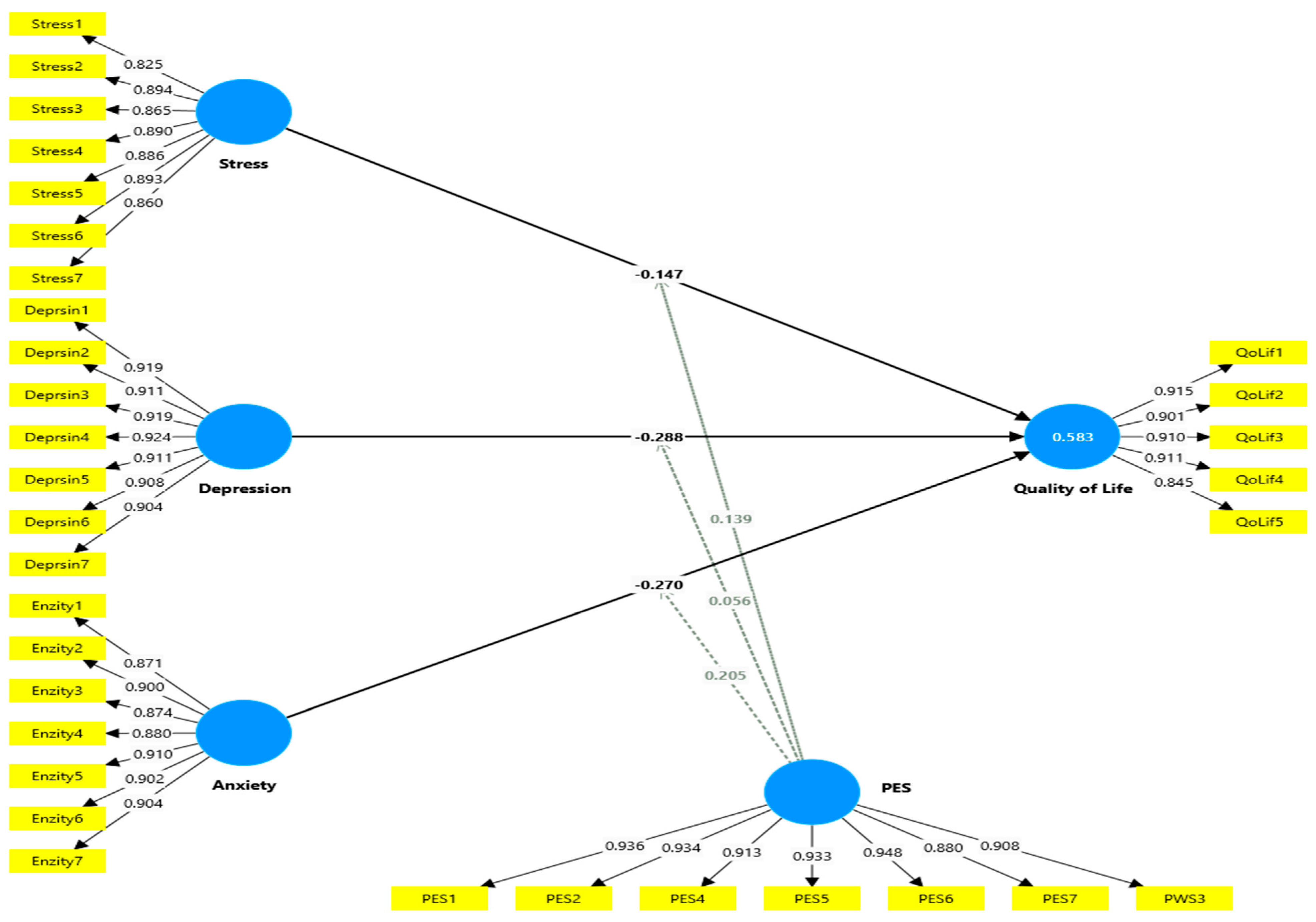

5.2. Tier One: Measurement Model Results for Validity and Relaibilty

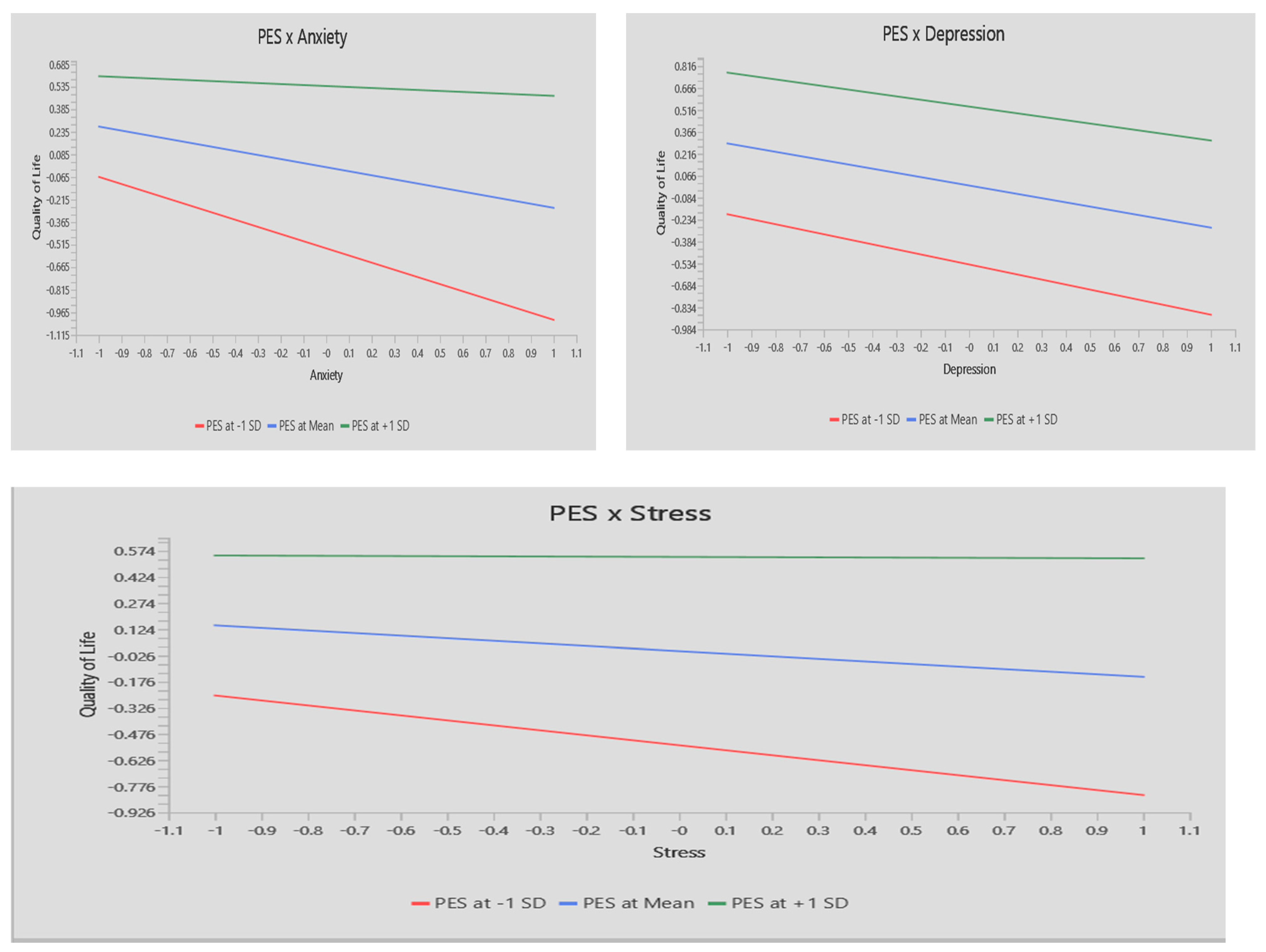

5.3. Tier-Two: Structural Model Results

6. Discussion

7. Limitations and Future Research Opportunities

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Abbreviations | Item | References |

| Perceived emotional support | Shakespeare-Finch and Obs t [39] | |

| PES1 | There is someone I can talk to about the pressures in my life | |

| PES2 | There is at least one person that I can share most things with | |

| PES3 | When I am feeling down there is someone, I can lean on | |

| PES4 | There is someone in my life who I can get emotional support from | |

| PES5 | There is at least one person that I feel I can trust | |

| PES6 | There is someone in my life that makes me feel worthwhile | |

| PES7 | I feel that I have a circle of people who value me | |

| Mental health disorder | Lovibond; Lovibond [33] | |

| Depression | ||

| I couldn’t seem to experience any positive feeling at all | ||

| I found it difficult to work up the initiative to do things | ||

| I felt that I had nothing to look forward to | ||

| I felt downhearted and blue | ||

| I felt I wasn’t worth much as a person | ||

| I was unable to become enthusiastic about anything | ||

| I felt that life was meaningless | ||

| Anxiety | ||

| Enzity1 | I was aware of dryness of my mouth | |

| Enzity2 | I experienced breathing difficulty (e.g., excessively rapid breathing, breathlessness in the absence of physical exertion) | |

| Enzity3 | I experienced trembling (e.g., in the hands) | |

| Enzity4 | I was worried about situations in which I might panic and make a fool of myself | |

| Enzity5 | I felt I was close to panic | |

| Enzity6 | I felt scared without any good reason | |

| Enzity7 | I was aware of the action of my heart in the absence of physical exertion (e.g., sense of heart rate increase, heart missing a beat) | |

| Stress | ||

| Stress1 | I found it hard to wind down | |

| Stress2 | I tended to overreact to situations | |

| Stress3 | I felt that I was using a lot of nervous energy | |

| Stress4 | I found myself getting agitated | |

| Stress5 | I found it difficult to relax | |

| Stress6 | I was intolerant of anything that kept me from getting on with what I was doing | |

| Stress7 | I felt that I was rather touchy | |

| Quality of life | Diener et al. [38] | |

| QoLif1 | In most ways my life is ideal | |

| QoLif2 | I am satisfied with my life | |

| QoLif3 | The conditions of my life are excellent | |

| QoLif4 | So far, I have gotten the important things I want in life | |

| QoLif5 | if I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing | |

References

- WHO. WHOQOL—Measuring Quality of Life|The World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/whoqol (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Fallowfield, L. What Is Quality of Life. Health Econ. 2009, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zayed, M.A.; Moustafa, M.A.; Elrayah, M.; Elshaer, I.A. Optimizing Quality of Life of Vulnerable Students: The Impact of Physical Fitness, Self-Esteem, and Academic Performance: A Case Study of Saudi Arabia Universities. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajati, F.; Ashtarian, H.; Salari, N.; Ghanbari, M.; Naghibifar, Z.; Hosseini, S.Y. Quality of Life Predictors in Physically Disabled People. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2018, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moustafa, M.A.; Elshaer, I.A.; Aliedan, M.M.; Zayed, M.A.; Elrayah, M.H. Risk Perception of Mental Health Disorders Among Disabled Students and Their Quality of Life: The Role of University Disability Service Support. J. Disabil. Res. 2024, 3, 20240013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shaer, E.A.; Aliedan, M.M.; Zayed, M.A.; Elrayah, M.; Moustafa, M.A. Mental Health and Quality of Life among University Students with Disabilities: The Moderating Role of Religiosity and Social Connectedness. Sustainability 2024, 16, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartz, J. All Inclusive?! Empirical Insights into Individual Experiences of Students with Disabilities and Mental Disorders at German Universities and Implications for Inclusive Higher Education. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Mental Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Tough, H.; Siegrist, J.; Fekete, C. Social Relationships, Mental Health and Wellbeing in Physical Disability: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, H.M.; Havercamp, S.M. Mental Health for People with Intellectual Disability: The Impact of Stress and Social Support. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2014, 119, 552–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliedan, M.M.; Elshaer, I.A.; Zayed, M.A.; Elrayah, M.H.; Moustafa, M.A. Evaluating the Role of University Disability Service Support, Family Support, and Friends’ Support in Predicting the Quality of Life among Disabled Students in Higher Education: Physical Self-Esteem as a Mediator. J. Disabil. Res. 2023, 2, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, F.T. Social Support as an Organizing Concept for Criminology: Presidential Address to the Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences. Justice Q. 1994, 11, 527–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, D.J.; Cooper, B.; Paul, S.; Humphreys, J.; Keagy, C.; Conley, Y.P.; Hammer, M.J.; Levine, J.D.; Wright, F.; Melisko, M. Evaluation of Coping as a Mediator of the Relationship between Stressful Life Events and Cancer-Related Distress. Health Psychol. 2017, 36, 1147–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakey, B.; Cronin, A. Low Social Support and Major Depression: Research, Theory and Methodological Issues. Risk Factors Depress. 2008, 385–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A.; McMunn, A.; Banks, J.; Steptoe, A. Loneliness, Social Isolation, and Behavioral and Biological Health Indicators in Older Adults. Health Psychol. 2011, 30, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Mann, F.; Lloyd-Evans, B.; Ma, R.; Johnson, S. Associations between Loneliness and Perceived Social Support and Outcomes of Mental Health Problems: A Systematic Review. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Hawkley, L.C.; Thisted, R.A. Perceived Social Isolation Makes Me Sad: 5-Year Cross-Lagged Analyses of Loneliness and Depressive Symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychol. Aging 2010, 25, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchino, B.N. Understanding the Links Between Social Support and Physical Health: A Life-Span Perspective with Emphasis on the Separability of Perceived and Received Support. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 4, 236–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottomley, A. The Cancer Patient and Quality of Life. Oncologist 2002, 7, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolote, J. The Roots of the Concept of Mental Health. World Psychiatry 2008, 7, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapolsky, R.M. Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers; Henry Holt & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, D.D.; Boynton, M.H.; Lytle, L.A. Multilevel Analysis Exploring the Links between Stress, Depression, and Sleep Problems among Two-Year College Students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2017, 65, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-D.; Hu, J.; Yen, C.-F.; Hsu, S.-W.; Lin, L.-P.; Loh, C.-H.; Chen, M.-H.; Wu, S.-R.; Chu, C.M.; Wu, J.-L. Quality of Life in Caregivers of Children and Adolescents with Intellectual Disabilities: Use of WHOQOL-BREF Survey. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2009, 30, 1448–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Zwart, P.L.; Jeronimus, B.F.; de Jonge, P. Empirical Evidence for Definitions of Episode, Remission, Recovery, Relapse and Recurrence in Depression: A Systematic Review. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2019, 28, 544–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association, F. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Am. Psychiatr. Assoc. 2013, 21, 591–643. [Google Scholar]

- Hansson, L. Quality of Life in Depression and Anxiety. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2002, 14, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P. Psychotherapy and Counselling for Depression; SAGE Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris, A. Editorial: What Is Depression? Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 58, 1287–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa-Camacho, F.J.; Romero-Limón, O.M.; Ibarrola-Peña, J.C.; Almanza-Mena, Y.L.; Pintor-Belmontes, K.J.; Sánchez-López, V.A.; Chejfec-Ciociano, J.M.; Guzmán-Ramírez, B.G.; Sapién-Fernández, J.H.; Guzmán-Ruvalcaba, M.J.; et al. Depression, Anxiety, and Academic Performance in COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miceli, M.; Castelfranchi, C. Expectancy and Emotion; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E.P.; Walker, E.F.; Rosenhan, D.L. Abnormal Psychology; WW Norton & Company, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, P. Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing: The Craft of Caring; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond, S.H.; Lovibond, P.F. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales; Psychology Foundation: Sydney, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.-H.; Dang, C.-Y.; Zheng, X.; Chen, W.-G.; Chen, I.-H.; Gamble, J.H. The Psychometric Properties of the DASS-21 and Its Association with Problematic Internet Use among Chinese College Freshmen. Healthcare 2023, 11, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.-H.; Liao, X.-L.; Jiang, X.-Y.; Li, X.-D.; Chen, I.-H.; Lin, C.-Y. Psychometric Evaluation of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) among Chinese Primary and Middle School Teachers. BMC Psychol. 2023, 11, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soria-Reyes, L.M.; Cerezo, M.V.; Alarcón, R.; Blanca, M.J. Psychometric Properties of the Perceived Stress Scale (Pss-10) with Breast Cancer Patients. Stress Health 2023, 39, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isha, A.S.N.; Naji, G.M.A.; Saleem, M.S.; Brough, P.; Alazzani, A.; Ghaleb, E.A.; Muneer, A.; Alzoraiki, M. Validation of “Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales” and “Changes in Psychological Distress during COVID-19” among University Students in Malaysia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakespeare-Finch, J.; Obst, P.L. The Development of the 2-Way Social Support Scale: A Measure of Giving and Receiving Emotional and Instrumental Support. J. Personal. Assess. 2011, 93, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Population and Housing Census Statistics. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.sa/statistics (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Avolio, B.J.; Yammarino, F.J.; Bass, B.M. Identifying Common Methods Variance with Data Collected from A Single Source: An Unresolved Sticky Issue. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 571–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E.; Brannick, M.T. Common Method Variance or Measurement Bias? The Problem and Possible Solutions. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods; SAGE Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 346–362. [Google Scholar]

- Reio, T.G. The Threat of Common Method Variance Bias to Theory Building. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2010, 9, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Brown, B.K. Method Variance in Organizational Behavior and Human Resources Research: Effects on Correlations, Path Coefficients, and Hypothesis Testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1994, 57, 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. How to Write Up and Report PLS Analyses. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Esposito Vinzi, V., Chin, W.W., Henseler, J., Wang, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 655–690. ISBN 978-3-540-32825-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2009; pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Mitchell, R.; Gudergan, S.P. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling in HRM Research. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 1617–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, G.T.M.; Hair, J.F.; Proksch, D.; Sarstedt, M.; Pinkwart, A.; Ringle, C.M. Addressing Endogeneity in International Marketing Applications of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. J. Int. Mark. 2018, 26, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.-M.; Proksch, D.; Ringle, C.M. Revisiting Gaussian Copulas to Handle Endogenous Regressors. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 46–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liengaard, B.D.; Becker, J.-M.; Bennedsen, M.; Heiler, P.; Taylor, L.N.; Ringle, C.M. Dealing with Regression Models’ Endogeneity by Means of an Adjusted Estimator for the Gaussian Copula Approach. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2024, 53, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Gupta, S. Handling Endogenous Regressors by Joint Estimation Using Copulas. Mark. Sci. 2012, 31, 567–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katon, W.J. Epidemiology and Treatment of Depression in Patients with Chronic Medical Illness. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 13, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beiter, R.; Nash, R.; McCrady, M.; Rhoades, D.; Linscomb, M.; Clarahan, M.; Sammut, S. The Prevalence and Correlates of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in a Sample of College Students. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 173, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Alghayth, K.M.; Alshahrani, B.F. Inclusion of Students with Intellectual Disability in Saudi Universities: Understanding the Gap Between Theory and Practice. Brit. J. Learn. Disabil. 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, F.S.; Abbas, A.O.; Al-Sify, H. Enhancing Quality of Learning Experiences for Students with Disabilities in Higher Education Institutions in Alignment with Sustainable Development Goals. J. Ecohumanism 2024, 3, 4911–4922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, Social Support, and the Buffering Hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, S.G.; Asnaani, A.; Vonk, I.J.J.; Sawyer, A.T.; Fang, A. The Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Review of Meta-Analyses. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2012, 36, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T. The Evolution of the Cognitive Model of Depression and Its Neurobiological Correlates. Am. J. Psychiatry 2008, 165, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| One single Gaussian Copula | |||

| β | t | p | |

| GC (Stress) -> Quality of Life | 0.161 | 1.020 | 0.093 |

| GC (Depression) -> Quality of Life | 0.096 | 1.883 | 0.072 |

| GC (Anxiety) -> Quality of Life | −0.172 | 1.084 | 0.278 |

| Two Gaussian Copula | |||

| First combination | |||

| GC (Stress) -> Quality of Life | 0.171 | 1.436 | 0.065 |

| GC (Depression) -> Quality of Life | 0.109 | 1.348 | 0.056 |

| Second combination | |||

| GC (Stress) -> Quality of Life | 0.147 | 1.862 | 0.074 |

| GC (Anxiety) -> Quality of Life | −0.102 | 0.656 | 0.512 |

| Third Combination | |||

| GC (Anxiety) -> Quality of Life | −0.276 | 1.847 | 0.065 |

| GC (Depression) -> Quality of Life | 0.113 | 1.190 | 0.059 |

| Three Gaussian Copula | |||

| GC (Stress) -> Quality of Life | 0.136 | 1.152 | 0.071 |

| GC (Depression) -> Quality of Life | 0.105 | 1.589 | 0.080 |

| GC (Anxiety) -> Quality of Life | −0.214 | 1.433 | 0.152 |

| Measure | Variable | Loading | CR | Cronbach’s a | AVE | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 0.967 | 0.970 | 0.835 | |||

| Deprsin1 | 0.919 | 4.758 | ||||

| Deprsin2 | 0.911 | 4.331 | ||||

| Deprsin3 | 0.919 | 4.968 | ||||

| Deprsin4 | 0.924 | 4.494 | ||||

| Deprsin5 | 0.911 | 4.633 | ||||

| Deprsin6 | 0.908 | 4.356 | ||||

| Deprsin6 | 0.904 | 4.047 | ||||

| Anxiety | 0.962 | 0.957 | 0.795 | |||

| Enzity1 | 0.871 | 4.051 | ||||

| Enzity2 | 0.900 | 4.637 | ||||

| Enzity3 | 0.874 | 3.885 | ||||

| Enzity4 | 0.880 | 4.745 | ||||

| Enzity5 | 0.910 | 4.401 | ||||

| Enzity6 | 0.902 | 4.122 | ||||

| Enzity7 | 0.904 | 4.328 | ||||

| Stress | 0.949 | 0.961 | 0.763 | |||

| Stress1 | 0.825 | 2.499 | ||||

| Stress2 | 0.894 | 4.733 | ||||

| Stress3 | 0.865 | 4.235 | ||||

| Stress4 | 0.890 | 3.854 | ||||

| Stress5 | 0.886 | 3.678 | ||||

| Stress6 | 0.893 | 4.152 | ||||

| Stress7 | 0.860 | 3.580 | ||||

| PES | 0.971 | 0.939 | 0.804 | |||

| PES1 | 0.936 | 2.291 | ||||

| PES2 | 0.934 | 4.083 | ||||

| PES3 | 0.908 | 2.261 | ||||

| PES4 | 0.913 | 4.244 | ||||

| PES5 | 0.933 | 3.779 | ||||

| PES6 | 0.948 | 4.046 | ||||

| PES7 | 0.880 | 2.727 | ||||

| QoL | 0.939 | 0.961 | 0.765 | |||

| QoLif1 | 0.915 | 4.355 | ||||

| QoLif2 | 0.901 | 3.742 | ||||

| QoLif3 | 0.910 | 4.001 | ||||

| QoLif4 | 0.911 | 3.796 | ||||

| QoLif5 | 0.845 | 2.335 |

| Anxiety | Depression | PES | Quality of Life | Stress | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | |||||

| Depression | 0.680 | ||||

| PES | 0.355 | 0.522 | |||

| Quality of Life | 0.486 | 0.415 | 0.240 | ||

| Stress | 0.614 | 0.330 | 0.127 | 0.379 | |

| PES x Anxiety | 0.362 | 0.510 | 0.190 | 0.468 | 0.074 |

| Anxiety | Depression | PES | Quality of Life | Stress | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deprsin1 | 0.613 | 0.919 | 0.468 | −0.366 | 0.330 |

| Deprsin2 | 0.575 | 0.911 | 0.462 | −0.391 | 0.280 |

| Deprsin3 | 0.626 | 0.919 | 0.435 | −0.362 | 0.315 |

| Deprsin4 | 0.591 | 0.924 | 0.484 | −0.319 | 0.290 |

| Deprsin5 | 0.573 | 0.911 | 0.471 | −0.331 | 0.256 |

| Deprsin6 | 0.581 | 0.908 | 0.425 | −0.360 | 0.282 |

| Deprsin7 | 0.629 | 0.904 | 0.458 | −0.404 | 0.326 |

| Enzity1 | 0.871 | 0.563 | 0.260 | −0.391 | 0.454 |

| Enzity2 | 0.900 | 0.605 | 0.213 | −0.500 | 0.517 |

| Enzity3 | 0.874 | 0.567 | 0.385 | −0.387 | 0.527 |

| Enzity4 | 0.880 | 0.567 | 0.352 | −0.363 | 0.553 |

| Enzity5 | 0.910 | 0.613 | 0.381 | −0.396 | 0.569 |

| Enzity6 | 0.902 | 0.577 | 0.252 | −0.429 | 0.519 |

| Enzity7 | 0.904 | 0.597 | 0.264 | −0.422 | 0.586 |

| PES1 | 0.282 | 0.445 | 0.936 | 0.244 | 0.061 |

| PES2 | 0.311 | 0.456 | 0.934 | 0.226 | 0.090 |

| PES4 | 0.332 | 0.472 | 0.913 | 0.187 | 0.163 |

| PES5 | 0.315 | 0.456 | 0.933 | 0.220 | 0.088 |

| PES6 | 0.273 | 0.443 | 0.948 | 0.262 | 0.074 |

| PES7 | 0.330 | 0.504 | 0.880 | 0.164 | 0.158 |

| PES3 | 0.331 | 0.486 | 0.908 | 0.181 | 0.157 |

| QoLif1 | −0.379 | −0.346 | 0.216 | 0.915 | −0.293 |

| QoLif2 | −0.414 | −0.369 | 0.189 | 0.901 | −0.330 |

| QoLif3 | −0.413 | −0.347 | 0.213 | 0.910 | −0.305 |

| QoLif4 | −0.410 | −0.376 | 0.196 | 0.911 | −0.307 |

| QoLif5 | −0.468 | −0.347 | 0.235 | 0.845 | −0.417 |

| Stress1 | 0.628 | 0.408 | 0.177 | −0.345 | 0.825 |

| Stress2 | 0.479 | 0.235 | 0.085 | −0.292 | 0.894 |

| Stress3 | 0.380 | 0.182 | 0.034 | −0.227 | 0.865 |

| Stress4 | 0.554 | 0.332 | 0.172 | −0.309 | 0.890 |

| Stress5 | 0.508 | 0.273 | 0.130 | −0.286 | 0.886 |

| Stress6 | 0.579 | 0.312 | 0.057 | −0.416 | 0.893 |

| Stress7 | 0.446 | 0.202 | 0.045 | −0.327 | 0.860 |

| Relationships | β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Stress -> Quality of Life (Accepted) | −0.147 | 2.320 | 0.020 |

| H2: Depression -> Quality of Life (Accepted) | −0.288 | 4.597 | 0.000 |

| H3: Anxiety -> Quality of Life (Accepted) | −0.270 | 3.428 | 0.001 |

| H4: PES × Stress -> Quality of Life (Accepted) | 0.139 | 2.460 | 0.014 |

| H5: PES × Depression -> Quality of Life (Rejected) | 0.056 | 0.931 | 0.352 |

| H6: PES × Anxiety -> Quality of Life (Accepted) | 0.205 | 3.026 | 0.002 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alyahya, M.; Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Sobaih, A.E.E. Emotional Support as a Lifeline: Promoting the Sustainability of Quality of Life for College Students with Disabilities Facing Mental Health Disorders. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1625. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041625

Alyahya M, Elshaer IA, Azazz AMS, Sobaih AEE. Emotional Support as a Lifeline: Promoting the Sustainability of Quality of Life for College Students with Disabilities Facing Mental Health Disorders. Sustainability. 2025; 17(4):1625. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041625

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlyahya, Mansour, Ibrahim A. Elshaer, Alaa M. S. Azazz, and Abu Elnasr E. Sobaih. 2025. "Emotional Support as a Lifeline: Promoting the Sustainability of Quality of Life for College Students with Disabilities Facing Mental Health Disorders" Sustainability 17, no. 4: 1625. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041625

APA StyleAlyahya, M., Elshaer, I. A., Azazz, A. M. S., & Sobaih, A. E. E. (2025). Emotional Support as a Lifeline: Promoting the Sustainability of Quality of Life for College Students with Disabilities Facing Mental Health Disorders. Sustainability, 17(4), 1625. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041625