1. Introduction

In an era of rapid change and mounting pressures, the field of sustainability increasingly recognizes that true progress extends beyond environmental and economic dimensions to encompass human well-being. Cultivating sustainable mental health and fostering sustainable learning are critical components in this broader sustainability agenda, as they empower individuals to adapt, thrive, and contribute meaningfully to society. By investing in the mental health and continuous development of learners, educational institutions not only enhance individual resilience but also lay the foundation for more innovative, equitable, and sustainable communities.

Recent trends in higher education underscore the importance of developing sustainable learners, students who not only excel academically but also sustain robust mental health and overall well-being over the long term. Educational well-being, which encompasses factors such as academic achievement, effective management of academic stress, and overall satisfaction with the educational experience, has been linked to numerous positive outcomes for students [

1,

2,

3]. However, these dimensions of well-being are increasingly challenged by changes in university life, including elevated levels of cynicism and difficulties in forming a strong institutional identity.

This emerging paradigm acknowledges that academic performance and well-being are deeply intertwined with psychological factors such as a sense of belonging, self-confidence, and the attitudes students hold toward their institutions. As universities strive to develop strategies that nurture these vital dimensions, it becomes essential to understand the interplay among key variables, namely, student cynicism, student–university identification, and academic self-efficacy. Moreover, mental health challenges such as anxiety, depression, and family-related issues are widely recognized as fundamental contributors to poor academic performance [

4]. Together, these insights pave the way for targeted interventions aimed at cultivating sustainable academic performance and sustaining overall mental health in higher education.

Student cynicism, characterized by skepticism and negative perceptions toward institutional practices, has been identified as a critical barrier to educational engagement and the sustaining of overall student well-being [

5]. It may manifest as a pervasive belief that the university prioritizes profit over student welfare, or that academic staff are disengaged and unsupportive, leading students to adopt a skeptical and detached attitude toward institutional processes [

5,

6]. For example, a student might question the fairness of grading systems or feel that university policies are implemented without considering student needs, resulting in reduced motivation to participate in academic activities. The previous literature underscores how student cynicism has become a widespread global attitude among university students [

7,

8]. Student cynicism has been associated with a number of critical consequences, like low academic success, overall discontent, voluntary physical seclusion, and the feeling of distance [

5,

9]. High levels of cynicism can erode trust in the academic environment and diminish the psychological connections students have with their institutions [

9]. This disconnection not only hampers academic motivation but may also contribute to adverse mental health outcomes by limiting access to vital social and emotional support systems [

10]. In this sense, cynicism indirectly poses a threat to the sustainability of both academic performance and mental health among college students.

Conversely, student–university identification represents a positive psychological resource that fosters a strong sense of belonging and connection to the academic community [

11]. A student with high level of identification may participate in campus events, or speak positively about their academic experience, while those with low levels of identification may feel alienated or express indifference toward institutional values. When students internalize their institution’s values and feel supported by its community, they are more likely to exhibit increased engagement, resilience, and motivation, all of which are essential for sustaining academic performance over time [

11]. Importantly, this identification might serve as a mediating mechanism through which the negative impacts of cynicism on academic performance may be alleviated. By reinforcing a supportive educational environment, institutions can counteract the detrimental effects of cynicism and promote a culture of inclusivity and well-being.

In addition to these factors, academic self-efficacy plays a crucial role in determining how effectively students can translate their sense of identification into tangible academic outcomes. Academic self-efficacy, defined as the belief in one’s capacity and ability to succeed academically, can amplify the positive effects of university identification [

12]. High self-efficacy leads students to approach challenges with a sense of competence and persistence, whereas low self-efficacy may result in avoidance, anxiety, and academic underperformance. Students with high levels of academic self-efficacy are more likely to leverage their sense of belonging into proactive learning behaviors and effective stress management, thereby enhancing their overall academic performance [

13]. This role of self-efficacy highlights the importance of individual psychological resources in sustaining both academic success and mental health.

By integrating these variables, the present study aims to examine a moderated mediation model wherein student–university identification mediates the relationship between student cynicism and academic performance, while academic self-efficacy moderates the link between identification and performance. This model not only elucidates the underlying mechanisms that impact academic outcomes but also indirectly contributes to the broader discourse on sustainable mental health in college students. Through this investigation, our research offers actionable insights for educators and policymakers seeking to design interventions that foster resilient and well-supported sustainable learners.

While prior studies have primarily focused on linear associations between psychological constructs in educational settings, growing evidence suggests that student attitudes and behaviors may also follow nonlinear trajectories [

14,

15]. This is particularly relevant in the context of student cynicism, which may not impact outcomes such as academic performance and institutional identification in a strictly proportional or monotonic manner. Students may tolerate certain levels of institutional or academic disappointment without significant drops in performance or engagement, but once a threshold is crossed, more dramatic disengagement may occur. Conversely, a moderate level of academic skepticism might prompt critical thinking and self-regulated learning, potentially enhancing performance, before cynicism becomes maladaptive.

To capture such possibilities, this study tests both linear and curvilinear (quadratic) relationships between student cynicism and key academic outcomes. The inclusion of curvilinear analyses allows us to identify potential threshold effects or patterns of diminishing/increasing returns that might be missed by conventional linear models. This dual analytic approach offers a more nuanced understanding of how different dimensions of cynicism, including policy-related, academic, social, and institutional, affect academic functioning.

Türkiye’s cultural context offers an important lens for interpreting student experiences in higher education, particularly regarding cynicism, institutional identification, and self-efficacy. As it is a country that scores relatively high in collectivism [

16], social connectedness and group loyalty play crucial roles in shaping individuals’ attitudes and behaviors. In collectivistic societies, people tend to emphasize group harmony and seek support from social networks when facing stress or dissatisfaction [

17]. Within this framework, identification with the university, as a key collective, may have a stronger impact on students’ academic engagement and performance, compared to individualistic contexts. This perspective aligns with findings that organizational identification effects are generally more pronounced in collectivist cultures, as individuals view institutional success as a shared goal and feel emotionally dependent on their collective [

18,

19].

Given these cultural dynamics, this study provides novel insights by examining student cynicism, university identification, and academic self-efficacy within the Turkish higher education system, a context that remains underexplored in the global sustainability literature. While prior research has primarily focused on individualistic cultures or generalized models of student behavior, this study’s findings shed light on how collectivist cultural norms can influence the pathways from psychological attitudes to academic outcomes. Furthermore, the study contributes to sustainability literature by addressing SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) in a culturally grounded manner. By emphasizing the roles of psychological resilience, institutional belonging, and self-efficacy, the study highlights how educational institutions in Türkiye can support student well-being and sustainable academic success in line with global development goals.

In sum, this study addresses a critical gap in the literature by linking psychological constructs to both sustainable academic performance and educational well-being. By highlighting the roles of cynicism, identification, and self-efficacy, and by incorporating both cultural considerations and non-linear modeling, we provide a comprehensive framework that informs strategies for developing sustainable academic environments. Ultimately, our findings contribute to ongoing efforts to promote mental health sustainability and academic resilience in higher education.

This study makes a significant contribution to the literature on student attitudes and academic functioning, as it is among the first studies to explicitly investigate non-linear relationships among student cynicism, academic performance, and identification. While this may seem like a technical detail, it entails considerable theoretical and practical implications. The inferences drawn from statistical models are only as valid as the assumptions underlying those models. Because linearity is implicitly assumed in most existing quantitative research, prior findings may not fully capture the complexity of real-world relationships. If the associations between key constructs are better described by curves than by straight lines, linear-only models risk oversimplifying or even misrepresenting the dynamics in play. By modeling more complex relationships, this study offers a more composite and arguably more realistic picture of how students’ attitudes, identification, and self-efficacy interact to shape academic outcomes, particularly within culturally distinctive educational systems like that of Türkiye.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Impact of Student Cynicism on Academic Performance

Andersson and Bateman [

20] describe cynicism as a both general and specific attitude marked by frustration, disillusionment, and negative feelings or distrust toward individuals, groups, ideologies, social conventions, or institutions. Predominantly considered an attitude [

20,

21,

22,

23], cynicism is distinguished from stable personality traits such as argumentativeness [

21] or pessimism [

24], and from emotional reactions like anger [

17] or cognitive constructs such as interpersonal trust [

22,

25,

26]. Its affective dimension includes feelings of hopelessness, frustration, distrust, inferiority, and humiliation [

9,

21].

Student cynicism refers to a negative attitude that emerges from the discrepancy between students’ expectations and their actual college experiences and is characterized by negative beliefs and disappointment [

5,

21,

27]. Early research by Becker and Geer [

28] focused on medical students, while subsequent studies by Pollay [

29] and Fulmer [

30] examined the cynical attitudes of business students. Later, Long [

31], and years later, Brockway and colleagues [

5], extended these investigations to undergraduate populations. Brockway et al. [

5] identified four dimensions of student cynicism: academic, social, policy-related, and institutional.

The rationale of the dimensions is grounded in established theoretical perspectives regarding the specificity of attitudinal targets. While cynicism is broadly recognized as an attitude [

21,

22], there is debate regarding the level of specificity of the objects toward which cynical attitudes are directed [

5]. Conceptualizing the college environment as comprising distinct academic and social microenvironments, Brockway et al. [

5] proposed that students develop targeted cynical attitudes toward different domains of the college experience [

5]. Specifically, they identified academic cynicism (negative attitudes toward the academic environment), social cynicism (cynicism regarding social opportunities on campus), and policy-related cynicism (distrust of college administrators and their policies). Furthermore, Brockway et al. [

5] extended the model to include institutional cynicism, a more global and generalized form of cynicism directed at the college, and encompassing dissatisfaction across multiple domains [

5].

As an attitude, cynicism is generally expected to lead to adverse outcomes, including dissatisfaction, negative emotions, reduced well-being, and even increased dropout rates [

5,

22,

32,

33,

34]. According to the Conservation of Resource theory [

35], individuals with cynical attitudes are more prone to burnout, prompting them to conserve their energy to prevent further resource loss.

While student cynicism, academic disengagement, and burnout are related constructs, it is crucial to differentiate them for conceptual clarity. Student cynicism includes cognitive and affective components, along with typically negative behavioral intentions [

5,

36]. In contrast, academic disengagement reflects a lack of behavioral and emotional involvement in learning tasks, as shown through reduced effort, absenteeism, or withdrawal from academic activities [

37]. It is task-oriented and does not involve evaluations of the broader institutional context. Student burnout includes emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced academic efficacy [

38]; it results from excessive academic demands, and leads to poor performance and health issues [

39]. Cynicism can arise from negative beliefs about the academic environment [

40]. Depersonalization involves a cold, passive attitude toward studies as a defense against stress [

41], while cynicism targets broader institutional issues and expresses distrust or disillusionment [

12,

42]. Both share psychological distance, but cynicism is broader in scope.

Cynicism reflects a mental and emotional disengagement from academic studies, often manifesting as detachment, indifference, or even hostility toward various aspects of educational experience [

7,

43]. It is closely linked to dissatisfaction, negative emotions, and a diminished sense of well-being, which in turn can negatively impact mental health and life satisfaction [

5]. Prior research has established a negative relationship between students’ cynical attitudes and their overall life satisfaction [

44,

45]. Similarly, a study examining nursing students found that academic, social, and institutional cynicism were all negatively associated with mental health outcomes [

10]. Given that mental health serves as a critical foundation for both individual and community well-being, enabling individuals to cope with stress, work productively, and contribute meaningfully to society [

46], understanding the detrimental effects of cynicism on student well-being becomes essential.

As a component of academic burnout, cynicism, along with feelings of inadequacy, has been associated with poor academic performance and maladaptive motivational tendencies [

38,

47]. School-related cynicism is characterized by emotional disengagement from coursework, loss of interest in academic progress, and a perception that school-related tasks are meaningless [

7,

48]. Furthermore, feelings of inadequacy in academic settings often manifest as a perceived lack of competence and low motivation toward achievement. Empirical evidence suggests that students experiencing high levels of cynicism, low professional efficacy, and overall burnout tend to have lower GPAs [

49].

The Conservation of Resources (COR) theory [

35] offers a perspective which is valuable for understanding the relationship between student cynicism and academic performance. According to COR theory, individuals strive to acquire, preserve, and protect valuable resources, including psychological and emotional assets. When students develop cynical attitudes that are marked by frustration, distrust, and disillusionment, they may perceive their academic environment as a threat to these resources. This perceived resource depletion can lead to burnout, reduced motivation, and disengagement from academic tasks, ultimately resulting in lower academic performance.

Previous research has consistently linked student cynicism to decreased academic performance, typically assuming a negative linear relationship (e.g., [

38,

47]). However, this assumption may oversimplify the complexity of the phenomenon. Emerging theoretical and empirical perspectives suggest that the relationship between cynicism and performance may follow a non-linear pattern [

14,

15].

Moderate levels of cynicism may serve adaptive functions, such as promoting critical thinking or acting as a coping strategy for institutional stressors, thereby potentially enhancing performance [

50,

51,

52]. Conversely, very low or very high levels of cynicism may undermine motivation, engagement, and overall functioning [

14]. For instance, Brandes and Das proposed an inverted U-shaped relationship, where moderate cynicism supports performance, but extreme levels are detrimental [

14].

This idea is echoed in Högberg’s [

15] argument that inconsistent findings across mental health and performance research may stem from overlooked non-linear dynamics; both low- and high-performing students may suffer psychological distress, albeit for different reasons [

15]. Such patterns challenge the dominant assumption of monotonic effects in quantitative research.

Further, Aiken and West (1991) emphasize that relying solely on linear models can obscure more complex relationships [

53]. Without tests for quadratic effects, researchers risk missing meaningful patterns such as U-shaped or inverted U-shaped relationships that provide a better fit for the data. Therefore, this study investigates both linear and curvilinear (quadratic) associations between various dimensions of student cynicism (policy-related, academic, social, and institutional) and academic performance to capture the full complexity of these effects. Building on these theoretical and empirical foundations, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: There are both linear and curvilinear (quadratic) relationships between student cynicism (policy-related, academic, social, and institutional) and academic performance.

2.2. The Effect of Student Cynicism on Student–University Identification

Social identity refers to the aspect of an individual’s self-concept derived from their awareness of belonging to a social group, along with the value and emotional significance attached to that membership [

54]. Social identity theory posits that individuals tend to categorize themselves into various groups based on attributes such as their abilities, nationality, religion, and socio-economic status [

55]. This categorization fosters group homogeneity by reinforcing interpersonal relationships among group members [

56].

A specific application of this concept is organizational identification, which describes an individual’s sense of belonging to an organization. This form of identification extends beyond the organization’s structure to include its members and activities [

57]. Individuals who strongly identify with their organization are more inclined to support and contribute positively to its success [

11]. Recent research has expanded this framework to explore how both current and potential customers develop identification with organizations (e.g., [

57,

58]). Analogously, Bhattacharya and Sen [

59] suggest that, similar to employees, customers, and by extension, students, develop identification with the institutions they are associated with, such as schools, colleges, and universities. In support of this, Bask and Salmela-Aro [

60] argue that although students are not employees, their engagement in activities like attending classes, completing assignments, and studying can be considered akin to “work”.

Pinna et al. [

61] define student–university identification as the extent to which students perceive themselves as sharing the defining attributes and values of their university, thereby fulfilling one or more of their personal identity needs. This identification not only promotes solidarity and mutual support between students and their institutions but also fosters extra-role behaviors such as advocacy, increased affiliation, and active participation in future university activities. From an institutional perspective, strong university identification is particularly important for enhancing graduation rates and event attendance and attracting prospective students [

62]. Consequently, student–university identification has been widely examined in research regarding its antecedents and outcomes (e.g., [

63,

64,

65]). Mael and Ashforth [

63] demonstrated that alumni identification is linked to the distinctiveness and prestige of their alma mater, while Kim et al. [

65] found that strong identification significantly boosts students’ willingness to support their university.

Organizational identification is a multidimensional construct comprising cognitive, emotional, and evaluative components [

66]. The cognitive component reflects an individual’s rational recognition of being part of an organization, the emotional component relates to their affective attachment to it, and the evaluative component pertains to their positive or negative assessment of the organization. Since cynicism stems from unmet expectations, it is likely to have a negative impact on organizational identification, particularly in terms of its evaluative aspect [

67,

68].

Social Identity Theory [

55] offers a strong theoretical framework for examining the relationship between student cynicism and student–university identification. This theory suggests that individuals categorize themselves into social groups and derive a sense of self from their group memberships. When students strongly identify with their university, they tend to develop positive emotional connections, a sense of loyalty, and greater engagement [

56]. However, cynicism toward the university can lead students to psychologically distance themselves from the institution, thereby weakening their identification with it.

Similarly, Organizational Disidentification Theory [

69] posits that individuals may actively disidentify with an organization when they perceive it to be inconsistent with their values or expectations. In the context of student cynicism, dissatisfaction with academic policies, social experiences, or institutional decisions can contribute to a rejection of university affiliation, further diminishing student–university identification.

Empirical studies have consistently demonstrated a negative relationship between cynicism and organizational identification. Mäkikangas et al. [

70] found a strong inverse correlation between the two variables. Similarly, Bedeian [

71] reported a significant negative effect of cynicism on organizational identification. More recently, Tong et al. [

72] highlighted that this negative relationship is moderated by psychological detachment, suggesting that the degree of disengagement may influence the strength of the association.

However, student–university identification may be influenced by varying degrees of student cynicism. While prior studies generally predict a negative, linear relationship between cynicism and identification (e.g., [

70,

71]), it is also plausible that this relationship exhibits non-linear dynamics. For instance, mild skepticism may prompt students to engage more deeply with institutional values, while severe cynicism may result in alienation. Hence, we examine both linear and curvilinear forms of this relationship to capture a broader range of psychological responses and potential turning points. Based on these theoretical and empirical insights, the second hypothesis of this study is proposed as follows:

H2: There are both linear and curvilinear (quadratic) relationships between student cynicism (policy-related, academic, social, and institutional) and student–university identification.

2.3. The Mediating Role of Student–University Identification in the Relationship Between Student Cynicism and Academic Performance

The Social Identity Approach [

73,

74] provides a strong theoretical foundation for understanding the effect of student–university identification on academic performance. This approach distinguishes between personal identity and social identity, emphasizing that individuals define themselves in relation to the groups they psychologically identify with. When individuals find a group meaningful, they internalize its values and norms, which influences their attitudes, motivations, and behaviors [

75]. In the academic context, students who identify strongly with their university are more likely to align their personal goals with the institution’s academic expectations, fostering engagement and effort toward academic success [

76].

Prior research highlights the crucial role of social identification in academic performance. Students with a strong sense of belonging and identification with their institution exhibit greater engagement, motivation, and academic achievement [

77,

78,

79]. Feelings of connectedness to school have been linked to positive attitudes toward learning, lower absenteeism, and higher academic performance [

80,

81,

82]. Conversely, when students develop cynical attitudes toward their university, they may experience psychological detachment, weakening their identification with the institution. This detachment can reduce motivation and engagement, negatively affecting their academic performance.

Despite the well-established negative relationship in workplace settings between cynicism and performance [

83], some studies have suggested a potential positive association [

14]. This inconsistency suggests the need to explore underlying causal mechanisms, particularly through mediating variables. Research in organizational behavior has identified mediators such as organizational citizenship behavior [

84] and motivation [

85] with respect to the cynicism–performance link. Moreover, although not explicitly testing a mediation model, Tuna et al. [

86] found that organizational identification and cynicism together accounted for 42% of the variance in employee performance. These findings suggest that identification may be a key factor influencing the impact of cynicism on performance.

Further supporting this mediation model, studies have demonstrated that identification-related constructs play a mediating role in performance outcomes. In the workplace, a sense of belonging significantly mediates the relationship between burnout and job performance [

87]. Similarly, in educational settings, school burnout has been found to mediate the relationship between school belonging and academic achievement [

88], highlighting the importance of identification in mitigating burnout and enhancing performance. Given that cynicism is a core component of burnout, these findings suggest that student–university identification may serve a similar mediating function in academic settings.

Taken together, these theoretical and empirical insights suggest that when cynicism is high, student–university identification weakens, leading to reduced academic engagement and lower performance. Conversely, when cynicism is low, students are more likely to develop a stronger sense of identification, which fosters motivation and engagement, ultimately improving academic performance.

While most mediation models assume linearity, the interplay between cynicism, identification, and performance may be more complex. A curvilinear pathway may exist whereby the effect of cynicism on identification, and thus on performance, follows a non-monotonic pattern. By testing both linear and curvilinear mediating paths, we aim to identify whether the strength or the direction of the indirect effects vary depending on the degree of cynicism. In light of the reviewed literature and findings, the third hypothesis is proposed as follows:

H3: Student–university identification mediates both the linear and curvilinear (quadratic) relationships between student cynicism (policy-related, academic, social, and institutional) and academic performance.

2.4. The Moderating Role of Academic Self-Efficacy in the Relationship Between Student–University Identification and Academic Performance

Self-efficacy, a central concept in Social Cognitive Theory [

89], refers to an individual’s belief in their ability to successfully execute the behaviors required to achieve specific goals. Within an academic context, this is often conceptualized as academic self-efficacy (ASE), students’ judgments of their capacity to attain educational objectives [

12]. Academic self-efficacy is shaped by direct experiences, social interactions, and personal achievements, influencing students’ motivation, perseverance, and learning strategies [

90]. Research consistently demonstrates that individuals with high levels of academic self-efficacy are more engaged in learning, invest greater effort, and more often persist through academic challenges, all of which contribute to better academic performance [

91,

92].

The relationship between academic self-efficacy and academic performance has been extensively studied across various educational levels, including higher education [

13]. Studies have examined ASE across different levels of specificity, such as self-efficacy for completing subject-specific tasks [

93], achieving specific grades [

94], and succeeding in university courses in general [

95,

96]. Meta-analyses confirm a positive correlation between ASE and academic performance, consistently reporting moderate effect sizes [

13,

97]. Moreover, high ASE is linked to increased well-being and academic satisfaction [

98,

99], while students with lower ASE tend to experience more academic stress and disengagement.

Beyond its direct impact on academic success, self-efficacy also interacts with students’ social identities and institutional belonging. Individuals are naturally inclined to identify with groups that enhance their self-esteem and align with their aspirations [

100]. This is particularly relevant in academic settings, in which students who strongly identify with their university are more likely to view institutional success as personal success [

100]. Given that self-efficacy is positively associated with college satisfaction [

99,

101], it is reasonable to assume that students with higher academic self-efficacy may be more inclined to identify with their university, strengthening the positive effects of identification on academic performance.

While a strong sense of student–university identification generally promotes better academic outcomes, the extent to which this identification translates into higher performance can depend on a student’s confidence in their academic abilities. Students with high ASE are more likely to leverage their institutional identification to enhance motivation, manage academic stress effectively, and actively engage in their coursework. In contrast, students with low ASE may struggle to translate their sense of belonging into tangible academic benefits, as doubts about their own competence may undermine their ability to capitalize on the resources and support offered by their institution.

This conditional effect aligns with Social Cognitive Theory [

102], which posits that self-efficacy influences individuals’ capacity to mobilize resources, persist through challenges, and regulate their behavior effectively. Consequently, ASE may function as a moderator, strengthening the positive impact of student–university identification on academic performance when ASE is high, while weakening this relationship when ASE is low.

Academic self-efficacy is widely recognized as a crucial moderator in educational contexts, often amplifying the positive effects of engagement-related constructs. While prior studies have established its moderating role in linear relationships, it remains unclear whether self-efficacy also influences non-linear effects. For instance, at very low or high levels of identification, students with high self-efficacy might still perform well, their self-efficacy buffering them against the adverse effects of misalignment or disengagement. Thus, we explore whether academic self-efficacy moderates both the linear and the curvilinear effects of student–university identification on performance.

Based on the above evidence and discussions, the fourth hypothesis is proposed as follows:

H4: Academic self-efficacy moderates the relationships between student–university identification and academic performance, such that both the linear and the curvilinear effects of identification on performance vary by levels of academic self-efficacy.

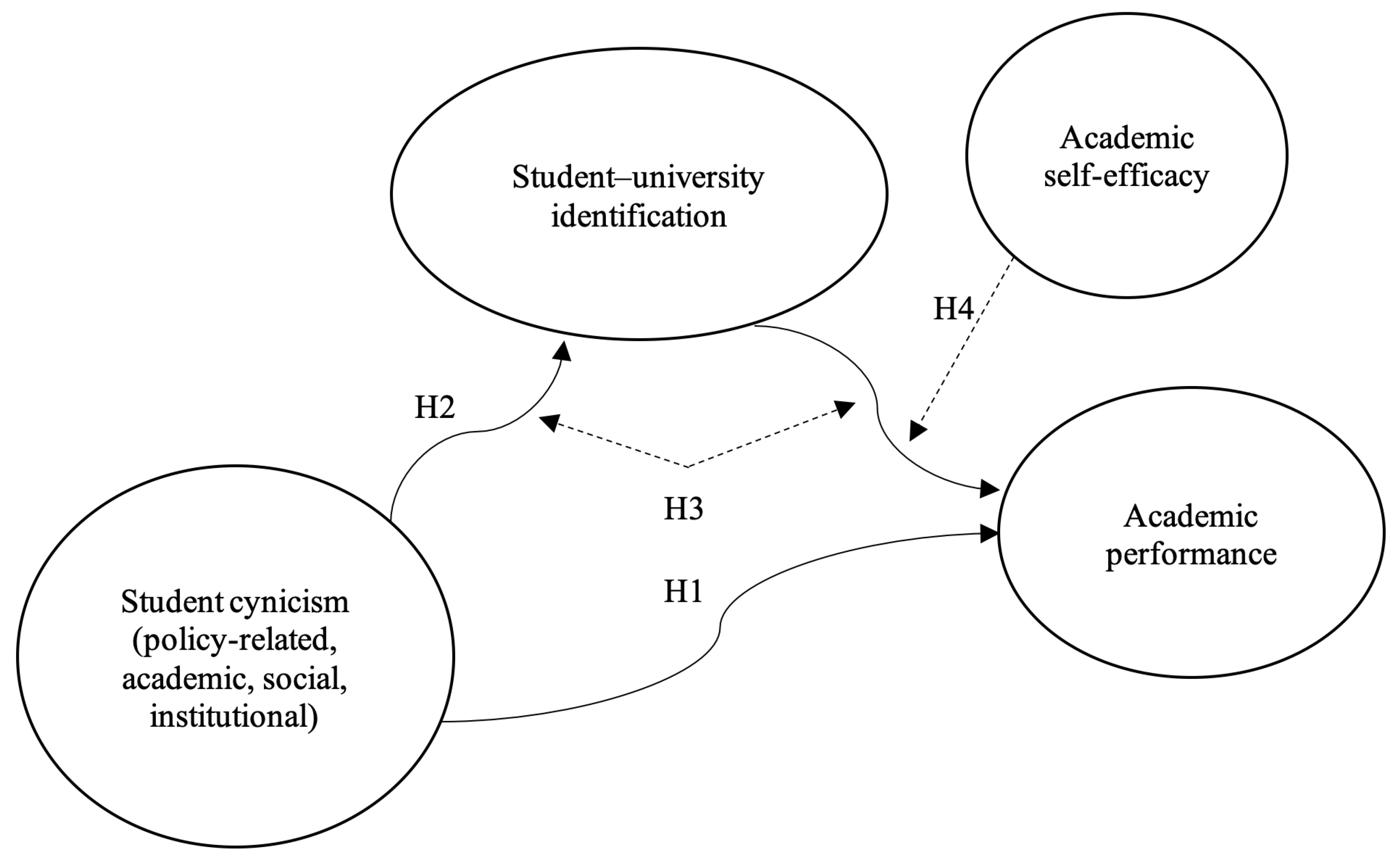

The model and hypotheses of the study are illustrated in

Figure 1.

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

The convenience technique, a type of non-probability sampling comprising available and easy-to-reach participants, is applied in the present work. In order to test the hypotheses and achieve the goals of the study, data were collected from students of an university in Ankara, Türkiye. Data collection took place between February 2023 and May 2023. This university is a medium-sized institution that offers a diverse range of academic programs and serves a large student population, enhancing the representativeness of our sample. The university is recognized for its diversity in terms of academic discipline, gender, and age, which helped ensure a broad demographic coverage in our study. In addition, university entrance exams in Türkiye are administered through a centralized system, and students can come from all over the country. While this is true for all universities, collecting data from a single institution allows for greater generalizability of the findings.

The participants were requested not to disclose their identity on the questionnaires, and they were assured of confidentiality. A total of 630 fully answered questionnaires were returned from the initial 750, achieving a completion rate of 84%. As for gender, 51.9% of the participants were female and 48.1% were male. Most of the students (78.1%) were aged between 20 and 25, and 18.1% of the total were younger than 20. The year-based distribution is as follows: freshman, 24%; sophomore, 29.7%; junior, 24.1%; and senior, 22.2%. These figures are consistent with the overall distribution of the university’s students, which implies that the sample can be assumed to be representative of the entire universe. While the use of convenience sampling within a single institution limits the generalizability of the findings to other universities or cultural contexts, the diversity within the university population provides some confidence in the internal validity of the study’s results.

The classes of the participants are almost equally distributed, as in the following: 1st class, 24%; 2nd class, 29.7%; 3rd class, 24.1%; and 4th class, 22.2%. These figures are consistent with the overall statistical profile of the university; thus, the sample can be assumed to be representative of the university.

3.2. Measures

Student Cynicism was measured by the 18-item self-report Cynical Attitudes Toward College Scale (CATCS) developed in [

5]. The items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from (1) “strongly disagree” to (5) “strongly agree”. A high score points out a high degree of student cynicism towards their college. In addition to the total score, which is referred to in the present study as “general student cynicism”, this scale includes 4 sub-scales: “policy-related cynicism” (4 items), “academic cynicism” (6 items), “social cynicism” (4 items), and “institutional cynicism” (4 items). In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the whole scale was 0.86 and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the subscales were 0.81 for “policy-related”, 0.71 for “academic”, 0.79 for “social” and 0.80 for “institutional”.

Academic self-efficacy was measured by the 7-item self-report scale developed by Jerusalem and Schwarzer [

103]. The items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from (1) “strongly disagree” to (5) “strongly agree”. A high score points out a high degree of self-efficacy.

Student–university identification was measured by Mael and Ashforth’s [

63] 6-item self-report scale. The items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from (1) “very weak” to (5) “very strong”. A high score indicates a high degree of student–university identification. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.83.

The academic performance of the participants was measured by self-report, by means of a question about their previous semester’s GPA. The grades were categorized and scored as 1 (between 0 and 0.5), 2 (between 0.5 and 1), 3 (between 1 and 1.5), 4 (between 1.5 and 2), 5 (between 2 and 2.5), 6 (between 2.5 and 3), 7 (between 3 and 3.5), or 8 (between 3.5 and 4). A high score represents a high level of general academic performance.

All of the original scales used in this study were adapted into Turkish using the translation–back translation method. However, to ensure linguistic and conceptual equivalence, the adaptation process followed standardized guidelines, including independent translations, expert evaluations, and pre-testing.

Based on the hypotheses outlined, here is the formal description of the model and its corresponding regression formulas:

- Equation for H1

(Academic Performance): academic_perf = b0 + b1 · (cyn_policy) + b2 · (cyn_academic) + b3 · (cyn_social) + b4 · (cyn_institutional) + b5 · (cyn_policy2) + b6 · (cyn_academic2) + b7 · (cyn_social2) + b8 · (cyn_institutional2) + ϵ

- Equation for H2

(Student–University Identification): stu_univ_id = b0 + b1 · (cyn_policy) + b2 · (cyn_academic) + b3 · (cyn_social) + b4 · (cyn_institutional) + b5 · (cyn_policy2) + b6 · (cyn_academic2) + b7 · (cyn_social2) + b8 · (cyn_institutional2) + ϵ

- Equation for H3

(Mediation of Student–University Identification): academic_perf = b0 + b1 · (stu_univ_id) + b2 · (cyn_policy) + b3 · (cyn_academic) + b4 · (cyn_social) + b5 · (cyn_institutional) + b6 · (cyn_policy2) + b7 · (cyn_academic2) + b8 · (cyn_social2) + b9 · (cyn_institutional2) + ϵ

- Equation for H4

(Moderation of Academic Self-Efficacy): academic_perf = b0 + b1 · (stu_univ_id) + b2 · (ASE) + b3 · (stu_univ_id × ASE) + b4 · (cyn_policy) + b5 · (cyn_academic) + b6 · (cyn_social) + b7 · (cyn_institutional) + b8 · (cyn_policy2) + b9 · (cyn_academic2) + b10 · (cyn_social2) + b11 · (cyn_institutional2) + ϵ

where academic_perf (academic performance) is the dependent variable and stu_univ_id is student–university identification. ASE is academic self-efficacy; cyn_policy, cyn_academic, cyn_social, and cyn_institutional are the cynicism dimensions; (·2) represents the quadratic terms. ϵ is the error term.

4. Results

To assess the validity and reliability of the measurement model, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted using key fit indices, including χ

2/df, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Additionally, the Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) were examined to evaluate construct reliability and convergent validity. The results are presented in

Table 1. In the first step, the alternative structures have been explored by testing single-, two-, three-, and four-factor structures of the Student Cynicism scale to determine the best fit. The alternative results establish that the four-factor structure has acceptable fit indices for acceptance when compared to the others. Accordingly, Student Cynicism was assessed across four dimensions: Policy-Related, Academic, Social, and Institutional. The overall model fit was χ

2/df = 3.78, CFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.89, and RMSEA = 0.074, which falls within an acceptable range for model adequacy. The CR values (ranging from 0.77 to 0.88) exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70, suggesting good internal consistency. Furthermore, the AVE values (ranging from 0.49 to 0.55) approached or exceeded the 0.50 benchmark, indicating moderate convergent validity. Student–University Identification exhibited strong model fit, with χ

2/df = 2.73, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, and RMSEA = 0.053, suggesting an excellent fit. The construct’s CR (0.79) was above the recommended threshold, and its AVE (0.50) met the minimum requirement for acceptable convergent validity. Academic Self-Efficacy showed a reasonable fit to the data, with χ

2/df = 3.76, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.92, and RMSEA = 0.078. The construct also demonstrated satisfactory reliability (CR = 0.78) and convergent validity (AVE = 0.50). All constructs demonstrated acceptable composite reliability (CR > 0.70), indicating internal consistency. The AVE values for most factors were at or near the recommended threshold of 0.50, supporting moderate convergent validity. In the second step, the measurement model’s results indicated an acceptable fit across the three primary constructs: Student Cynicism, Student–University Identification, and Academic Self-Efficacy. Overall, the CFA results support the structural integrity of the measurement model, indicating that the constructs of Student Cynicism, Student–University Identification, and Academic Self-Efficacy are well-represented by their respective measurement items. The fit indices suggest that the model is appropriate for further structural analysis and hypothesis testing.

Table 2 presents the means, reliabilities, and correlations among the research variables. Student Cynicism (Policy-Related, Academic, Social, and Institutional) is positively correlated, with Policy-Related showing the strongest link to Academic (r = 0.550,

p < 0.01) and Institutional forms of cynicism (r = 0.495,

p < 0.01). Student–University Identification is negatively related to all forms of cynicism, indicating that higher identification with the university relates to lower cynicism. Academic Self-Efficacy negatively correlates with cynicism across all dimensions, suggesting that a higher level of self-efficacy relates to lower cynicism. It also has a positive relationship with University Identification (r = 0.196,

p < 0.01). Academic Performance is negatively correlated with cynicism and positively correlated with Self-Efficacy (r = 0.346,

p < 0.01), indicating that a higher level of Self-Efficacy is related to higher Academic Performance and less cynicism. Overall, higher levels of self-efficacy and stronger university identification are associated with lower cynicism and better academic outcomes.

The first hypothesis explored the relationships between each dimension of cynicism (Policy-Related, Academic, Social, and Institutional) and Academic Performance. The AIC/BIC values in

Table 3 indicate that the cynicism models have determinate fit values. Cynicism toward policies significantly undermines Academic Performance, as evidenced by a negative linear association (b

1 = −0.951,

p = 0.030), and the nonsignificant positive quadratic effect suggests that cynicism toward policies significantly decreases Academic Performance. Academic cynicism strongly predicts lower Academic Performance, with a pronounced negative linear effect (b

1 = −1.951,

p < 0.001). Interestingly, a significant U-shaped curve (b

2 = 0.207,

p = 0.007) reveals that beyond a certain threshold (vertex ≈ 4.71), extreme cynicism may lead to a slight improvement in performance, hinting at a complex, dynamic relationship. Cynicism directed toward Social aspects shows no meaningful link to Academic Performance, with both linear (b

1 = −0.370,

p = 0.523) and quadratic (b

2 = 0.051,

p = 0.508) effects being statistically insignificant, suggesting that social cynicism does not play a substantial role in academic outcomes. Cynicism toward institutions is associated with reduced Academic Performance, as demonstrated by a significant negative linear effect (b

1 = −0.989,

p = 0.003) and a nonsignificant positive quadratic term (b

2 = 0.096,

p = 0.068). These findings partially support H1, highlighting the negative associations associated with Policy-Related, Academic, and Institutional cynicism, but with curvilinear patterns complicating the relationships, while Social cynicism shows no clear impact.

The second hypothesis explored the relationships between each dimension of cynicism (Policy-Related, Academic, Social, and Institutional) and Student–University Identification (

Table 3). The quadratic model testing the relationship between Policy-Related cynicism and Student–University Identification did not support a nonlinear relationship. Neither the linear term (b

1 = −0.188,

p = 0.464) nor the quadratic term (b

2 = 0.009,

p = 0.807) was significant, indicating no meaningful association. The model showed poor fit (AIC = 1624.57, BIC = 1642.29). The relationship between Academic cynicism and Student–University Identification showed no evidence of a nonlinear effect. The quadratic model revealed non-significant linear (b

1 = −0.384,

p = 0.200) and quadratic (b

2 = 0.011,

p = 0.803) terms. The model fit was slightly better than the Policy-Related model (AIC = 1592.55, BIC = 1610.27), but the results suggest that Academic cynicism does not significantly predict university identification. Social cynicism’s relationship with Student–University Identification also lacked a nonlinear pattern. The quadratic model showed no significant linear (b

1 = −0.078,

p = 0.818) or quadratic (b

2 = 0.002,

p = 0.972) effects. The model had the weakest fit (AIC = 1631.57, BIC = 1649.29), indicating that Social cynicism does not meaningfully influence university identification. The quadratic model for Institutional cynicism and Student–University Identification revealed a significant negative linear relationship (b

1 = −0.541,

p = 0.004) but no quadratic effect (b

2 = 0.023,

p = 0.428), suggesting that the relationship is linear rather than curvilinear. This model had the strongest fit (AIC = 1515.62, BIC = 1533.34), indicating that higher levels of Institutional cynicism are associated with lower levels of university identification. Partially supporting H2, the findings suggest that Institutional cynicism has a linear negative association with university identification, while nonlinear effects were not evident across any dimension.

The third hypothesis explored the mediating role of Student–University Identification in the relationships between each dimension of cynicism (Policy-Related, Academic, Social, and Institutional) and Academic Performance (

Table 4). The mediation analysis results are provided, including the average causal mediation effect (ACME), average direct effect (ADE), total effect, and proportion mediated for each dimension. The mediation analysis for Policy-Related cynicism showed that Student–University Identification did not significantly mediate the relationship between cynicism that is Policy-Related and Academic Performance. The ACME was non-significant at 0.050 (95% CI [−0.353, 0.23],

p = 0.770), indicating no indirect effect. However, the ADE was significant at −0.198 (95% CI [−0.329, −0.06],

p = 0.001), suggesting a direct negative effect of Policy-Related cynicism on Academic Performance. The total effect was marginally significant, at −0.248 (95% CI [−0.573, 0.05],

p = 0.087), and with a proportion mediated of 0.201 (95% CI [−2.647, 2.69],

p = 0.684), further confirming the lack of mediation. As for Academic cynicism, Student–University Identification did not mediate the relationship with Academic Performance. The ACME was non-significant, at 0.0367 (95% CI [−0.2775, 0.42],

p = 0.805), showing no indirect effect. The ADE was highly significant and negative, at −0.5524 (95% CI [−0.7036, −0.40],

p < 0.001), indicating a strong direct negative effect of Academic cynicism on Academic Performance. The total effect was significant, at −0.5157 (95% CI [−0.8375, −0.12],

p = 0.021), and with a proportion mediated of −0.0711 (95% CI [−2.0958, 0.40],

p = 0.826), reinforcing the absence of mediation. The mediation analysis for Social cynicism indicated no significant mediation effect through Student–University Identification. The ACME was non-significant, at −0.025 (95% CI [−0.50385, 0.26],

p = 0.820), showing no indirect effect. The ADE was also non-significant, at 0.031 (95% CI [−0.096, 0.160],

p = 0.640), suggesting no direct effect of Social cynicism on Academic Performance. The total effect was non-significant, at 0.006 (95% CI [−0.469, 0.310],

p = 0.990), and with a proportion mediated of −3.893 (95% CI [−4.552, 5.030],

p = 0.410), indicating no meaningful mediation. As for Institutional cynicism, Student–University Identification did not significantly mediate its relationship with Academic Performance. The ACME was non-significant, at −0.035 (95% CI [−0.488, 0.350],

p = 0.847), indicating no indirect effect. The ADE was highly significant and negative, at −0.322 (95% CI [−0.454, −0.190],

p < 0.001), demonstrating a direct negative effect of Institutional cynicism on Academic Performance. The total effect was marginally significant, at −0.3585 (95% CI [−0.7921, 0.02],

p = 0.062), and with a proportion mediated of 0.099 (95% CI [−4.0945, 2.85],

p = 0.785), confirming no significant mediation. Based on these findings, H3 has not been supported with respect to the mediating role of Student–University Identification.

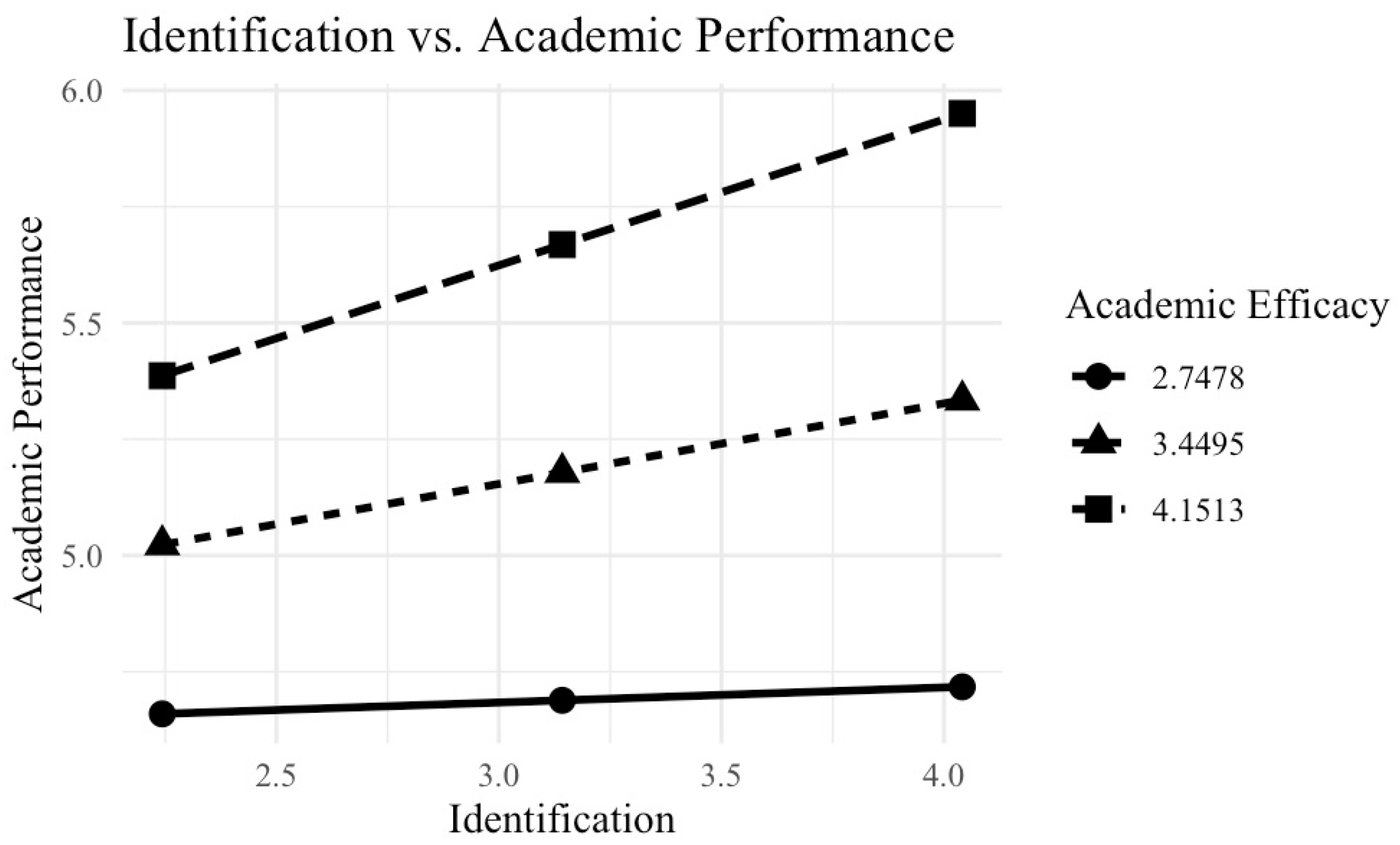

The fourth hypothesis explored the moderating role of Academic Self-Efficacy (ASE) in-between Student–University Identification and Academic Performance (

Table 5). The non-linear moderation analysis revealed a significant positive linear relationship between Student–University Identification and Academic Performance (β = 0.181,

p = 0.0078), indicating that higher levels of identification are associated with better academic outcomes. This relationship was moderated by ASE, as evidenced by a significant interaction between the linear term of identification and ASE (β = 0.216,

p = 0.0135). This suggests that the positive effect of Student–University Identification on Academic Performance is stronger for students with higher levels of ASE. The quadratic relationship between Student–University Identification and Academic Performance was not significant (β = −0.050,

p = 0.358), indicating no curvilinear effect. Additionally, ASE did not moderate the quadratic relationship, as the interaction between the quadratic term of identification and ASE was non-significant (β = −0.053,

p = 0.444). This suggests that ASE does not influence any non-linear patterns between identification and Academic Performance. The overall moderation model was significant (F(5, 614) = 20.53,

p < 0.001), explaining 14.3% of the variance in Academic Performance (R

2 = 0.143). The findings highlight that ASE enhances the linear relationship between Student–University Identification and Academic Performance, but does not moderate any curvilinear effects; this supports H4 as to the linear relationship.

To put it more clearly, the connection between how students identify with their university and their academic performance becomes even more powerful for those who have higher levels of academic self-efficacy (

Figure 2).

5. Discussion

This study set out to explore the linear and nonlinear (quadratic) relationships between the dimensions of student cynicism, namely, policy-related, academic, social, and institutional, and academic performance, with particular attention to the mediating role of student–university identification and the moderating effect of academic self-efficacy. While the prior literature has predominantly assumed linear pathways, our integration of curvilinear models was guided by the notion that student attitudes and beliefs may not always exert effects in a straightforward manner, especially in culturally nuanced contexts like those associated with Türkiye.

The findings offer partial support for the hypothesized linear and curvilinear relationships. Specifically, H1 was supported, in the linear model, for all dimensions of cynicism except social cynicism, while only academic cynicism showed a significant U-shaped curvilinear effect on academic performance. This suggests that the negative impact of academic cynicism on performance may become more pronounced at extreme levels, whereas other types of cynicism exert linear effects which are more consistent. Interestingly, the curvilinear relationship indicates that extreme academic cynicism may also lead to a slight improvement in performance, hinting at a complex and dynamic interplay.

The negative linear associations align with existing research showing that students who perceive institutional failure or academic inefficiency tend to disengage and underperform. However, the curvilinear pattern found in academic cynicism suggests that mild skepticism may foster critical thinking and academic resilience. Once cynicism surpasses a certain threshold, however, it begins to hinder performance. This U-shaped curve reflects psychological theories proposing that moderate levels of skepticism can be adaptive, an idea particularly relevant in educational systems marked by perceived inequities or inefficiencies.

One plausible explanation for the non-significant association between social cynicism and academic performance is that social cynicism primarily reflects students’ perceptions of recreational and interpersonal aspects of university life, rather than concerns directly tied to academics or institutional functioning. Thus, dissatisfaction with social opportunities may not necessarily reduce engagement with academic work. Moreover, the cultural dynamics in Türkiye may help to explain this finding. In a context where social harmony and interpersonal cohesion are highly valued, students may compartmentalize broader societal distrust and maintain a sense of academic responsibility. Alternatively, cultural norms may discourage the expression of social distrust within institutional settings, thereby weakening its observable effect on academic outcomes.

Contrary to expectations (H2), only institutional cynicism showed a significant negative linear relationship with student–university identification, while none of the cynicism dimensions demonstrated curvilinear effects. This finding suggests that cynicism directed specifically at the institution, rather than toward the broader academic system or society, most directly undermines a student’s psychological bond with their university. The Turkish context offers a meaningful lens to interpret this result, as loyalty to institutions often stems from a collectivist mindset and expectations of fairness, transparency, and reciprocity. When these expectations are not met, students may emotionally withdraw from the institution, even if they continue to perform academically for instrumental reasons.

The lack of nonlinear effects may indicate that identification operates more like a threshold variable, one that is either present or absent, rather than one that varies significantly at different levels of cynicism. This could be influenced by the centralized and hierarchical nature of Turkish university administration, an aspect which may limit students’ perceived agency and flatten the relational dynamics between cynicism and identification.

Despite the theoretical justification, student–university identification did not significantly mediate the relationship between any dimension of cynicism and academic performance (H3). This unexpected finding may point to a disconnection between emotional affiliation and academic outcomes in contexts in which performance is driven primarily by external motivators, such as family expectations, job prospects, or standardized testing. Identification may be more relevant to long-term outcomes, such as alumni engagement or organizational commitment, rather than immediate academic performance. In Türkiye, where education tends to be instrumentalized, academic success may rely more on individual perseverance or family support than on emotional connection to the university.

As proposed in H4, academic self-efficacy moderated the linear relationship between student–university identification and academic performance, but no moderation was observed in the curvilinear models. This finding reinforces the critical role of self-efficacy as a personal resource that buffers the negative effects of institutional or interpersonal challenges. Students with high self-efficacy may sustain their levels of performance even when their identification with the university is weak, while those with low self-efficacy may depend more on their sense of institutional belonging to remain academically engaged. High self-efficacy is typically associated with stronger motivation, resilience, and adaptive learning strategies, enabling students to benefit more fully from academic and social advantages linked to identification. In contrast, students with low self-efficacy may struggle with self-doubt, lack of persistence, or ineffective learning habits, which can limit the impact of identification on academic performance, even if they feel a sense of belonging. The absence of curvilinear moderation may indicate that self-efficacy plays a stabilizing role in the model, acting more as a buffer than as a catalyst of complexity in these interactions.

Furthermore, the absence of significant effects of social cynicism on academic performance might reflect the cultural tendency to compartmentalize social dissatisfaction separate from academic responsibilities. In collectivist societies like Türkiye, maintaining social harmony and conforming to group norms are often prioritized. As such, students may suppress or dissociate negative social perceptions when it comes to performing academically, especially in highly competitive educational environments. These patterns suggest that cultural dynamics may shape not only how cynicism is experienced but also how it translates into academic behavior.

The findings hold cultural significance within the context of Turkish higher education, in which strong collectivist values shape students’ expectations and institutional experiences. In such cultures, universities function not only as academic spaces but also as key environments for identity formation and social belonging. The significant negative relationship between institutional cynicism and student–university identification underscores the central role of institutional trust in sustaining these psychological bonds. In Türkiye, loyalty to institutions is often grounded in cultural norms emphasizing fairness, transparency, and mutual respect. When these expectations are not met, such as when institutional actors are perceived as unaccountable or unresponsive, students may emotionally withdraw.

However, this emotional disengagement does not necessarily lead to reduced academic performance. The absence of a significant link between student–university identification and performance suggests that Turkish students may separate emotional affiliation from academic effort. In a context where education is highly instrumentalized, performance is often driven by external motivators like family expectations, standardized exams, or career goals. Identification may thus function more as a symbolic affiliation than a true motivational driver of academic behavior. These findings point to the importance of institutional credibility and fairness in shaping students’ emotional engagement, even if such engagement is not directly tied to their academic success.

The theoretical implications of these findings are significant, offering several contributions. First, they demonstrate the added value of nonlinear modeling in unpacking complex psychological constructs in the field of higher education, especially within culturally diverse contexts. Second, they highlight that not all forms of cynicism are equally damaging; academic and institutional cynicism deserve particular attention from educators and policymakers. Third, the non-significant mediating role of identification challenges the assumption that strengthening student–university bonds will automatically enhance academic outcomes. Interventions may need to focus more directly on building student capacity and efficacy, especially in performance-driven environments.

The findings of this study offer meaningful practical implications for institutions of higher education aiming to foster sustainable learning environments and promote psychological well-being among their students. Notably, the complex relationship between student cynicism and academic performance, particularly the curvilinear role of academic cynicism, highlights the need for institutions to adopt a more nuanced and individualized approach to student engagement and support.

While extreme levels of academic cynicism negatively impact performance, moderate levels may reflect adaptive skepticism and critical thinking. This suggests that universities should not aim to eliminate cynicism entirely, but rather create spaces where students can voice concerns constructively. Transparent academic policies, responsive governance practices, and inclusive decision-making structures can help to channel students’ academic dissatisfaction into productive dialogue, reducing alienation and enhancing engagement. These actions align closely with Sustainable Development Goal 4 (Quality Education), which calls for inclusive, equitable, and quality learning experiences.

At the same time, the strong negative effects of institutional cynicism on student–university identification underscore the importance of rebuilding trust between students and institutional actors. Institutions should invest in transparent communication, ensure fairness in academic practices, and actively involve students in institutional processes to foster a sense of ownership and shared purpose. These measures not only address cynicism at its root but also contribute to students’ emotional connection to their university, a vital component of mental health sustainability.

Given the absence of significant mediation by student–university identification, it becomes clear that identification alone may not suffice to sustain academic performance, especially in performance-driven contexts like Türkiye, in which external motivators (e.g., job prospects, familial expectations) often dominate. Therefore, boosting academic self-efficacy emerges as a more actionable pathway. Institutions should prioritize structured academic mentoring, personalized advising, and resilience-focused workshops to strengthen students’ belief in their own academic abilities. These resources can serve as protective factors, especially for students who lack strong identification with their institution, ensuring that they can continue to perform despite institutional shortcomings.

Faculty training programs should also address how to recognize and respond to signs of student disengagement, while encouraging pedagogical approaches that build confidence and competence. Active learning methods, formative feedback, and relational teaching practices can help to foster psychological resilience and long-term academic success.

From a sustainability perspective, enhancing students’ academic resilience and well-being not only supports better individual outcomes but also contributes to a healthier, more adaptable future workforce. Aligning educational practices with SDG 4 and SDG 8 (Decent Work, and Economic Growth) ensures that graduates are not only knowledgeable but also mentally prepared and emotionally equipped to thrive in complex, fast-changing professional environments.

In sum, higher education institutions, particularly in culturally collectivist contexts like Türkiye, should adopt a multifaceted approach to student development, one that addresses both emotional and performance-related dimensions. By focusing on trust-building, academic empowerment, and targeted support systems, universities can cultivate a generation of resilient, engaged, and sustainable learners.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the linear and nonlinear relationships between student cynicism (across policy-related, academic, social, and institutional dimensions), student–university identification, academic self-efficacy, and academic performance in the context of Turkish higher education. The findings revealed that while institutional cynicism significantly undermines students’ identification with their university, identification itself does not directly translate into improved academic performance. Furthermore, academic self-efficacy emerged as a critical buffer, strengthening the link between identification and performance only under certain conditions. Interestingly, the U-shaped relationship between academic cynicism and performance suggests that while moderate cynicism may hinder academic engagement, extreme levels might, paradoxically, be associated with modest rebounds in performance, possibly due to increased critical scrutiny or adaptive coping strategies. This nuance warrants further qualitative investigation.

These results underscore the complex interplay between emotional disengagement and academic functioning. In Türkiye’s collectivist educational culture, students may maintain their academic effort due to external motivators (e.g., family expectations, career goals), even when they feel disconnected from their institutions [

104]. This detachment, while functionally adaptive in the short term, may have longer-term consequences for student well-being, institutional trust, and sustained motivation.

From a practical standpoint, the findings emphasize the importance of promoting academic self-efficacy and institutional trust to build sustainable and mentally resilient learning environments. Institutions of higher education should invest in fair and transparent academic governance, implement inclusive communication practices, and create meaningful student involvement channels to reduce cynicism, especially at the institutional level. Additionally, strengthening students’ belief in their own academic capabilities through mentoring, feedback, and skill-building programs remains key to buffering the adverse effects of disidentification or dissatisfaction.

The study primarily relied on self-reported measures, including self-reported GPA, to assess academic performance. While we recognize that self-reports are susceptible to biases such as social desirability or recall bias, this approach was chosen due to the practical constraints of the research, including accessibility to participants and the nature of the variables under study. However, we agree that self-reported GPA may not fully capture objective academic performance and could introduce bias, as students may overestimate or underestimate their performance. To address this limitation, we suggest that future studies could enhance the accuracy of academic performance measurement by incorporating objective academic records or triangulating the self-reported GPA with instructor evaluations or other academic indicators, such as exam scores or project grades. While this would require more extensive data collection and coordination with academic staff, it would provide a more comprehensive and objective measure of academic performance.

We also acknowledge a concern regarding common method variance (CMV), which can occur when all data are collected using a single source or method (in this case, self-reports). To mitigate CMV, we took several steps in the design and implementation of the study. First, participants were assured of their anonymity and the confidentiality of their responses, which was intended to reduce social desirability bias and encourage honest reporting. Furthermore, we used well-established, validated scales to ensure that the questions were clear, unbiased, and designed to minimize the likelihood of participants responding in a socially desirable manner. Despite these efforts, we recognize that self-reported data are inherently vulnerable to biases, and we suggest that future research might address this concern by employing multiple data sources or employing longitudinal designs. Additionally, utilizing different methods (e.g., surveys, interviews, and archival data) could help mitigate the impact of CMV and provide a more robust picture of the variables under investigation.

Moreover, the sample was drawn from a specific context within higher education, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other institutions, cultural settings, or educational levels. In particular, the measurement of social cynicism may not have fully captured the complexity of students’ experiences, potentially contributing to the nonsignificant findings observed for this factor. Additionally, while this study sheds light on the relationships between student cynicism, university identification, academic self-efficacy, and performance, it is important to acknowledge that other unmeasured factors may have influenced these outcomes.

For instance, socioeconomic status (SES) can significantly impact students’ access to educational resources, perceived institutional support, and overall academic confidence. External stressors such as family responsibilities, part-time employment, or psychological health challenges may independently contribute to variations in academic performance and levels of cynicism. These factors may act as confounding variables, either amplifying or buffering the relationships observed in this study. Future research should incorporate SES indicators, stressor assessments, and additional psychological variables to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the determinants of student cynicism and academic success.

In conclusion, while we have taken steps to minimize the potential impact of self-report biases and CMV, we acknowledge these limitations and recommend that future research incorporate more objective measures and consider triangulating data from multiple sources to enhance the reliability and validity of the findings.

In conclusion, while the current study offers culturally grounded insights into the dynamics of cynicism, self-efficacy, and performance, it also points to the need for more integrative and methodologically diverse research. By fostering psychological resilience and institutional belonging, universities can better support sustainable learner development and contribute to broader goals such as mental well-being and inclusive educational quality.