Wine Tourism as a Tool for Sustainable Development of the Cultural Landscape—A Case Study of Douro Wine Region in Portugal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Principles of Sustainable Development

2.2. The Function of Winemaking in the Cultural Landscape

2.3. A Living Cultural Landscape

2.4. Wine Tourism as a Subject of Study in the Literature

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Materials

3.3. Methods

- -

- For stimulants:

- -

- For destimulants:

- x1—unstandardised variable for stimulant and destimulant indicators for the i-th spatial unit;

- x max.—maximum value for a given indicator among all surveyed spatial units;

- x min.—minimum value for a given indicator among all surveyed spatial units.

- Pd—demographic potential;

- Xi (1, 2, 3, 4)—normalised value of diagnostic indicator (1, 2, 3, 4) in spatial unit i;

- n—the number of diagnostic indicators.

4. Results

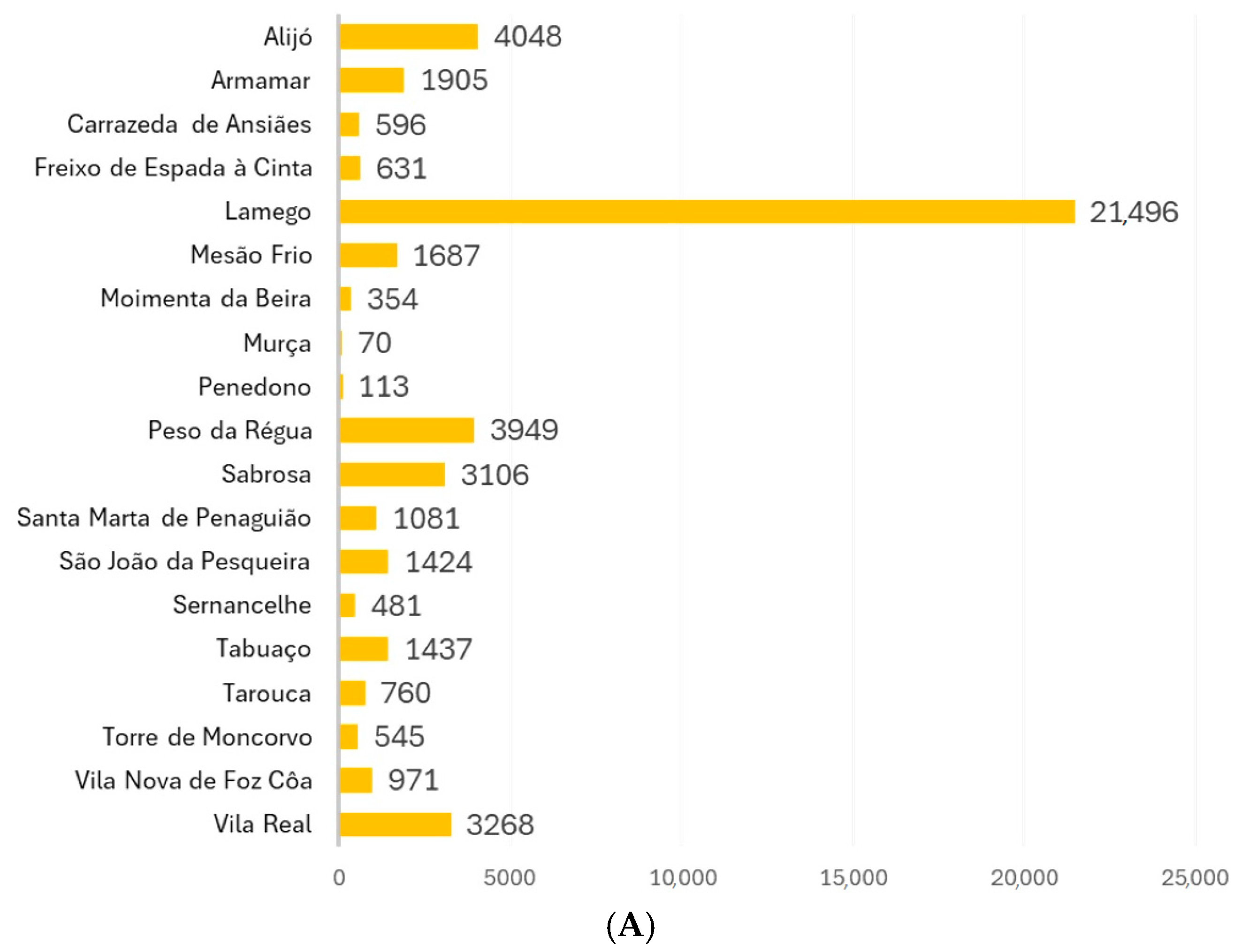

4.1. Demographic Potential and Sustainable Development

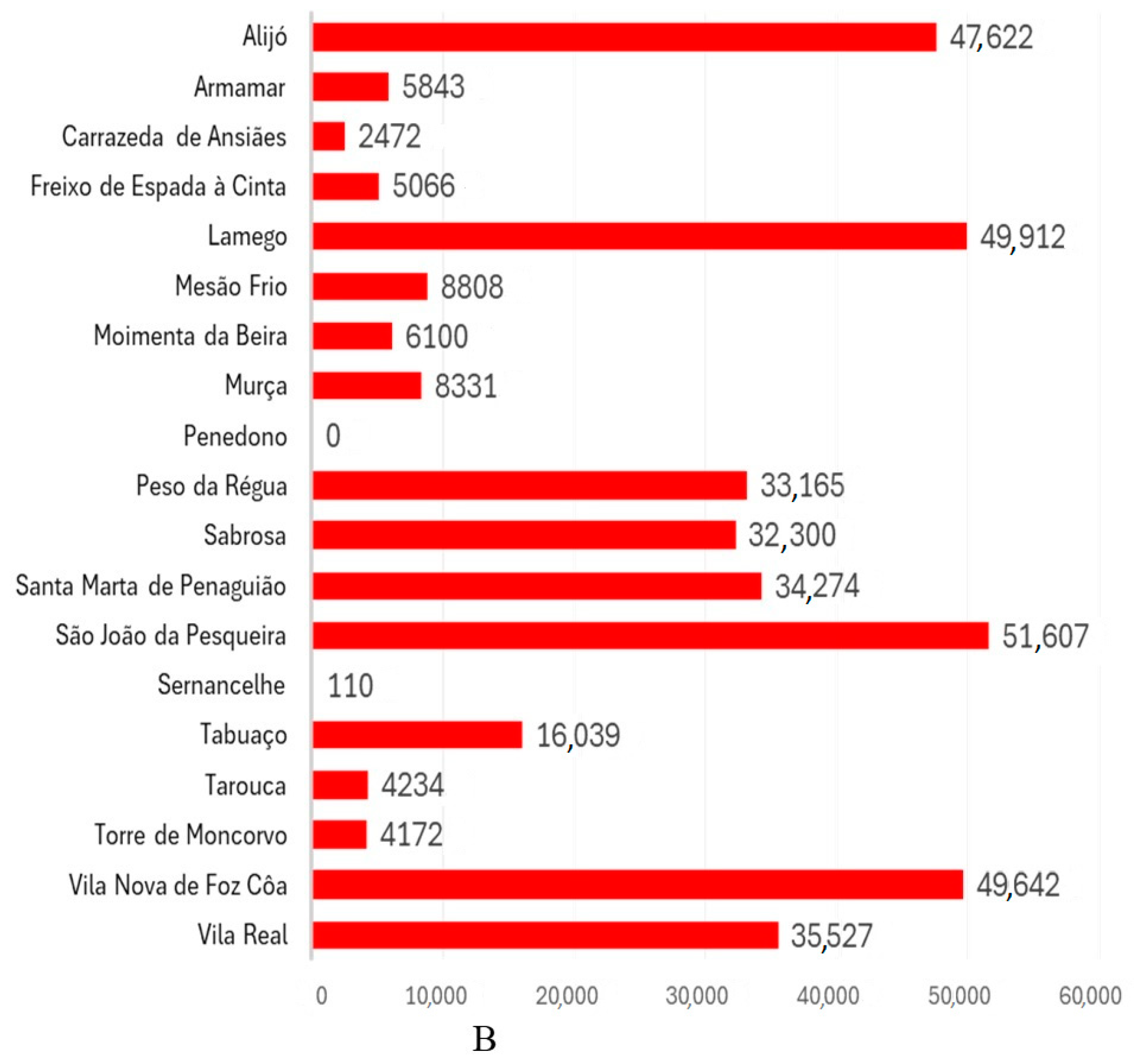

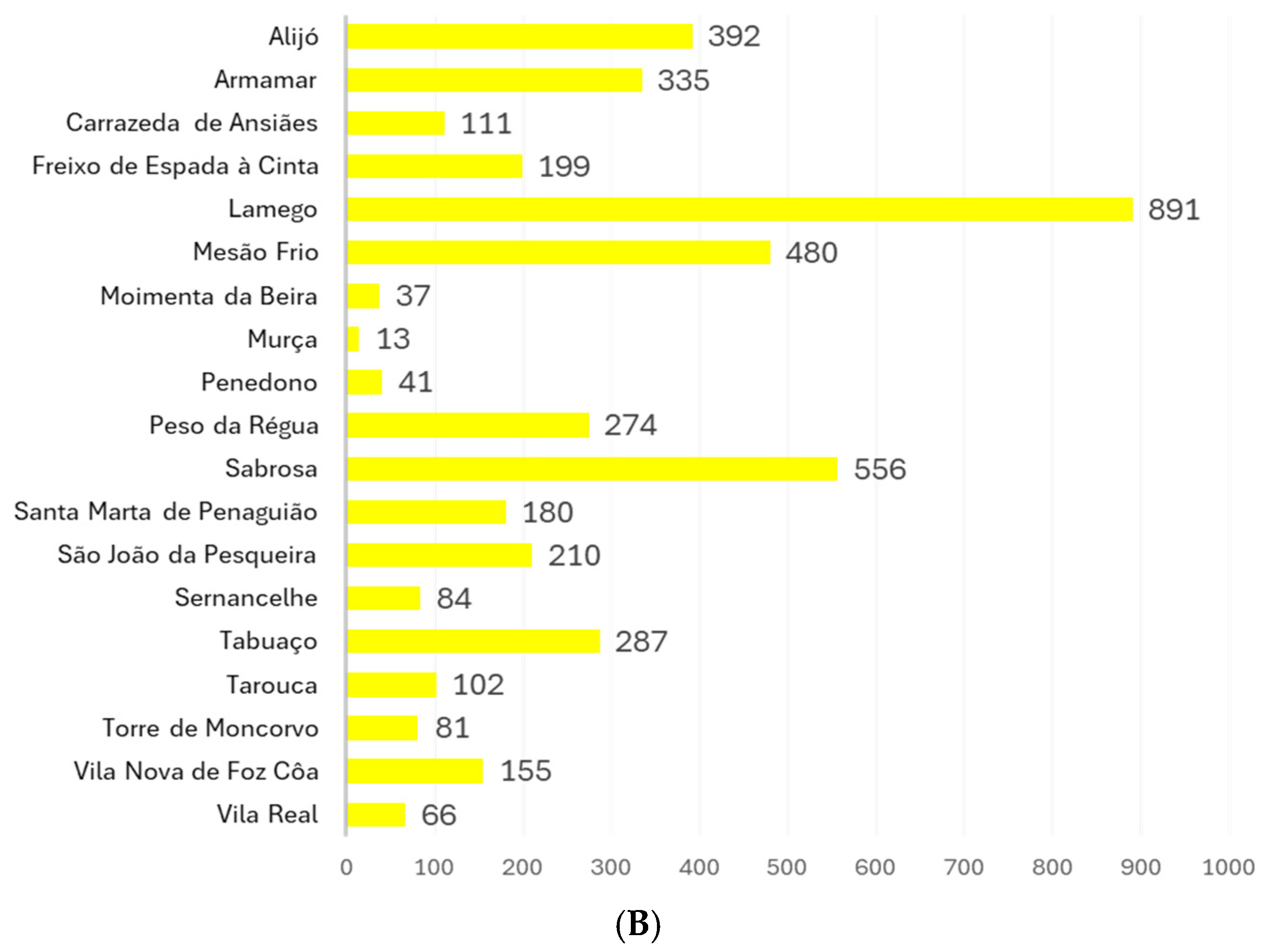

4.2. Wine Production

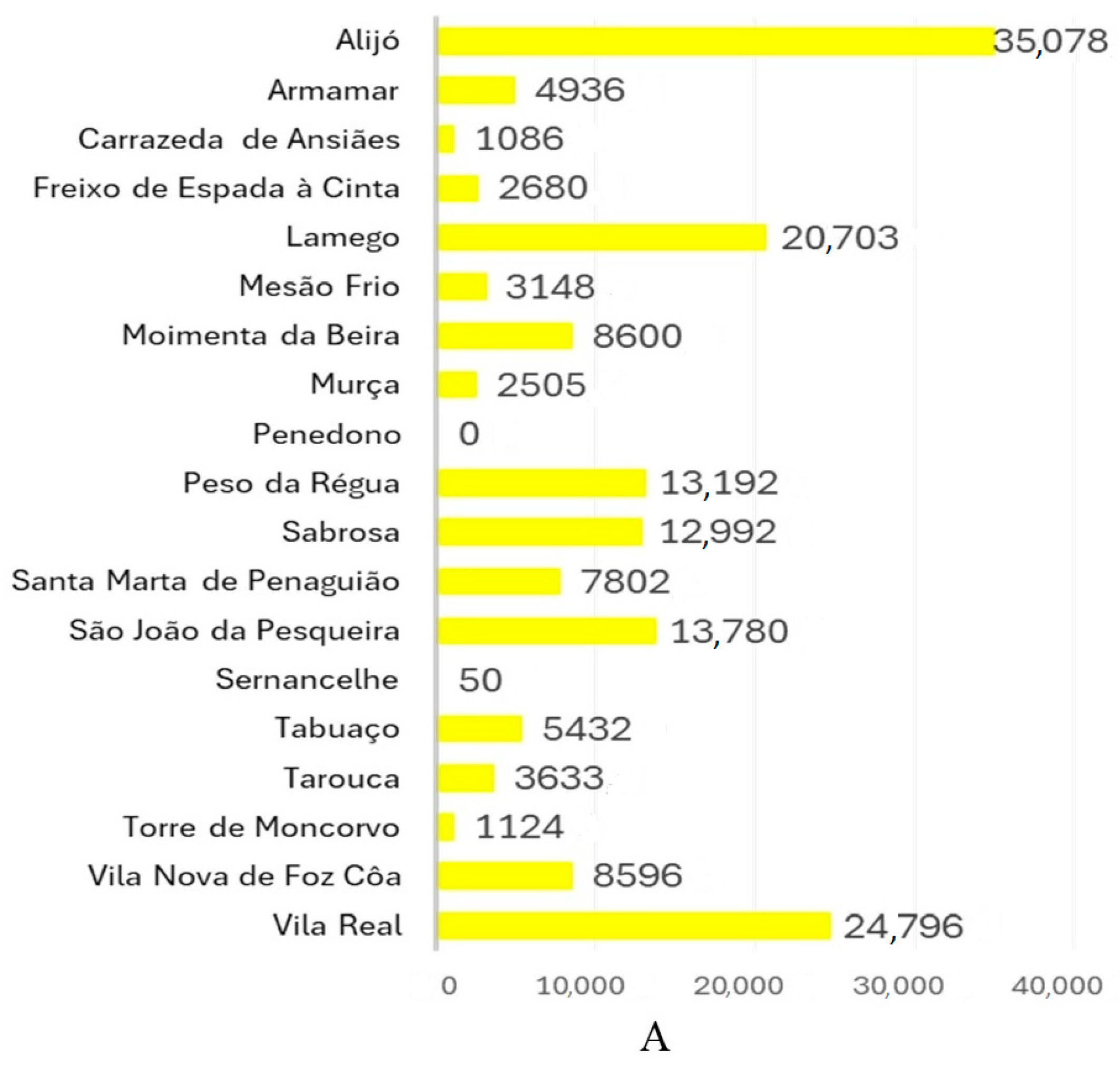

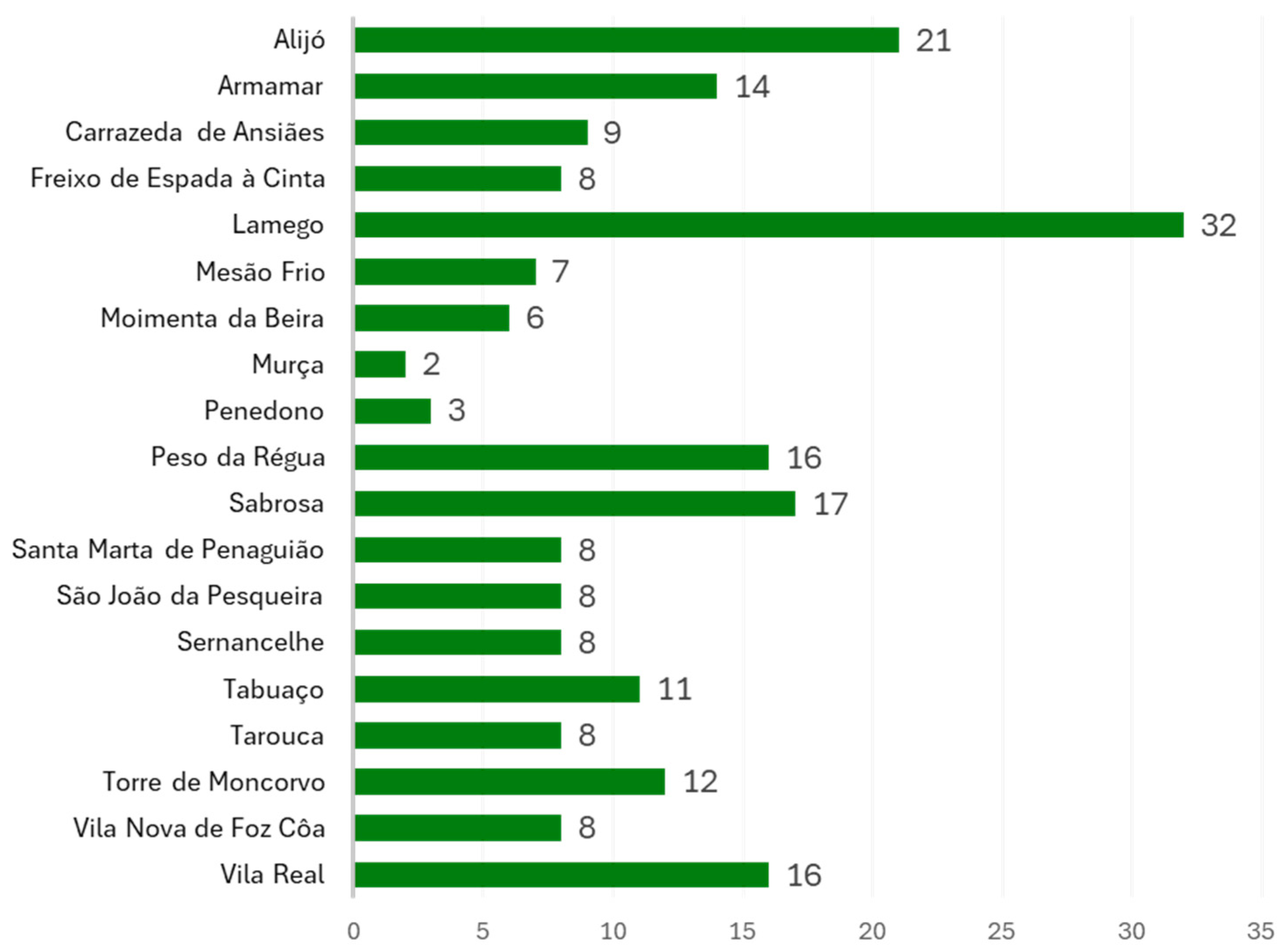

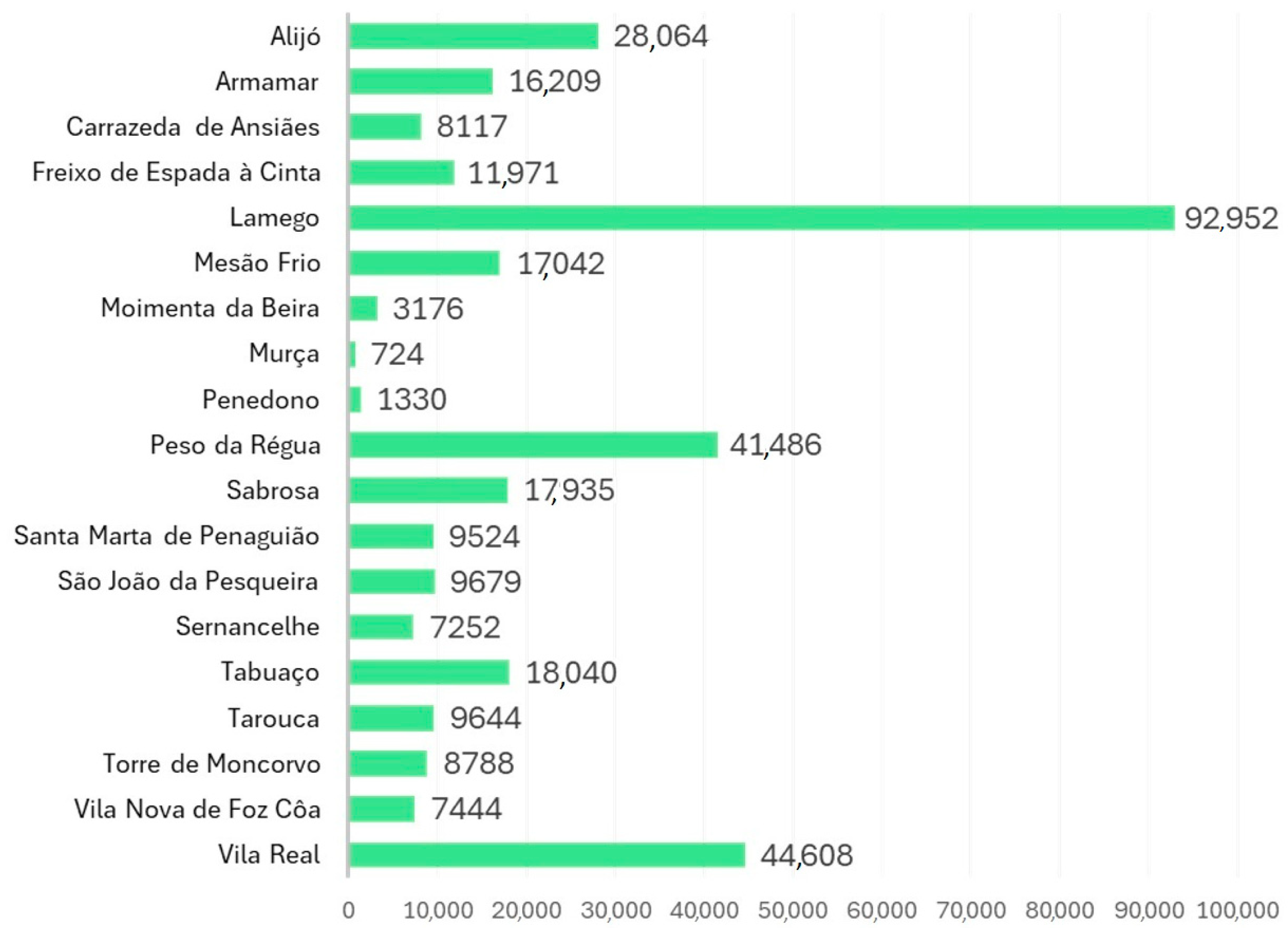

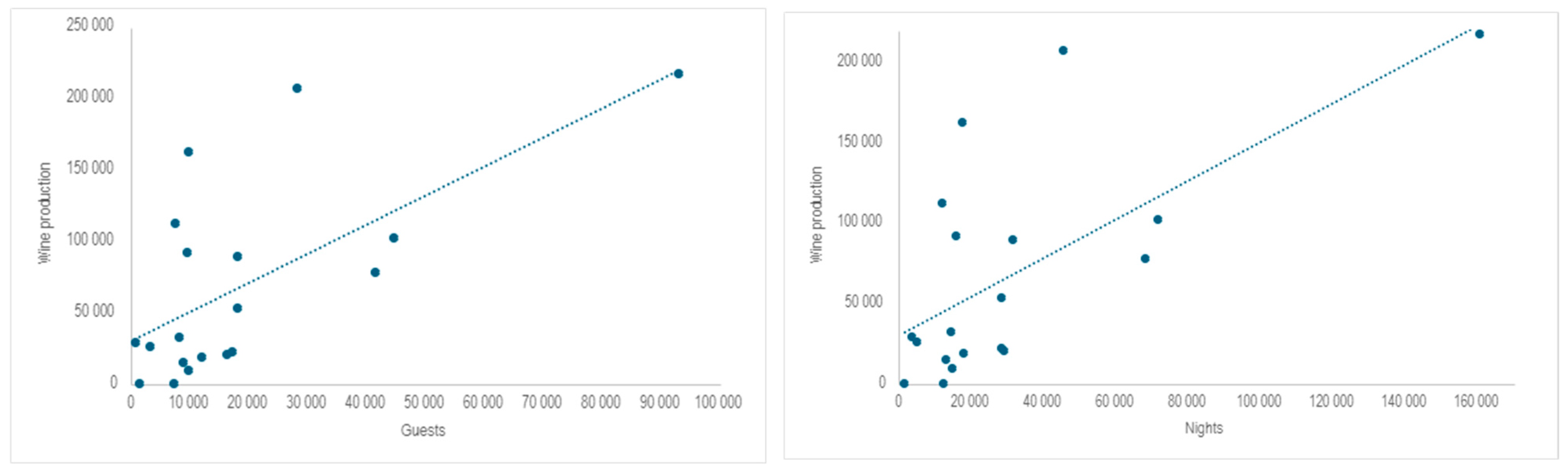

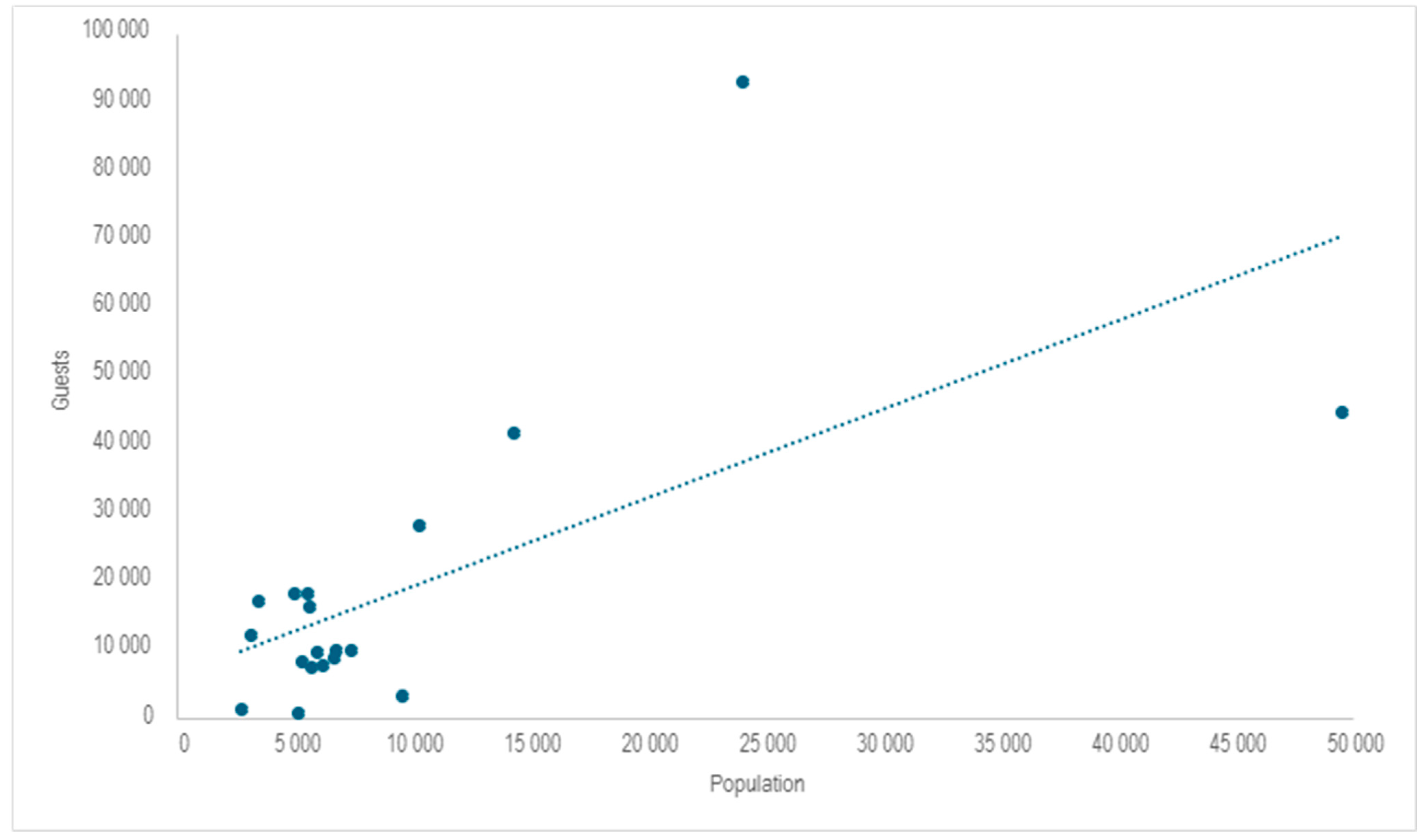

4.3. Wine Tourism as a Tool for Sustainable Development

- -

- A high level of tourist development was recorded in municipalities with high demographic potential (Lamego, Mesão Frio).

- -

- A medium-high level of tourist development was recorded in municipalities with low and very low demographic potential (Sabrosa, Carrazeda de Ansiães, Freixo de Espada à Cinta, Tabuaço).

- -

- A similarly high Schneider Index was recorded in the municipalities of Lamego, Freixo de Espada à Cinta, and Tabuaço.

- -

- As a tool for sustainable development, wine tourism should have an impact on the income of local residents. The assessment of the impact of tourism income for municipalities and on a per capita basis showed the following patterns: the highest income from tourism was recorded in Lamego, with the highest level of tourism development. At the same time, Lamego has the highest income per capita. The average income was recorded in municipalities with low demographic potential (Alijo, Peso da Régua, Sabrosa, Vila Real). The average income per capita was also recorded in these municipalities.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- -

- Difficult natural conditions (mountainous areas made of slate and granite rocks, a high and steep river valley);

- -

- Difficult infrastructural conditions (difficult to access in bad weather);

- -

- Demographics (increasing depopulation processes);

- -

- Scattered settlements (with limited access to schools and health care).

- -

- Improving tourism infrastructure, including accommodation in areas with low demographic potential. At the same time, this will contribute to increasing the number of jobs available, and this will not only occur during the grape harvesting period.

- -

- Greater activity to promote wine tourism, not only in the most well-known regions of the Douro but also in municipalities marginal to Porto.

- -

- Education and promotion of sustainability among local people.

- -

- Combining wine tourism with other forms of tourism.

- -

- Deepening cooperation and developing synergies between tourists and winemakers.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kruczek, Z. Enoturystyka w Polsce i na Świecie; Proksenia: Kraków, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Charzyński, P.; Gonia, A.; Podgórski, Z.; Kruger, A.A. Determinants of culinary tourism development in Pomeranian Voivodeship. J. Educ. Health Sport 2017, 7, 665–681. [Google Scholar]

- Charzyński, P.; Nowak, A.; Podgórski, Z. Turystyka winiarska na Ziemi Lubuskiej–historycznie uwarunkowana konieczność czy nowatorskie rozwiązanie. J. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 198–216. [Google Scholar]

- Głąbiński, Z. Turystyka winiarska-problemy terminologiczne, konsumenci i możliwości rozwoju. Ekon. Probl. Tur. 2018, 42, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Jezierska-Thöle, A.; Gwiaździńska-Goraj, M.; Dudzińska, M. Environmental, Social, and Economic Aspects of the Green Economy in Polish Rural Areas—A Spatial Analysis. Energies 2022, 15, 3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poczta, J.; Zagrocka, M. Uwarunkowania rozwoju turystyki winiarskiej w Polsce na przykładzie regionu zielonogórskiego. Tur. Kult. 2016, 5, 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Poitras, L.; Getz, D. Sustainable wine tourism: The host community perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2006, 5, 425–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardare, A. Consumer Role in Enotourism Development in the Republic of Moldova. Lucr. Semin. Geogr. Dimitri Cantemir 2015, 40, 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Johnson, G.; Cambourne, B.; Macionis, M.; Mitchell, R.; Sharples, L. Wine tourism: An Introduction. In Wine Tourism Around the World. Development, Management and Markets; Hall, C.M., Sharples, L., Cambourne, B., Macionis, N., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2000; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- González, C.; López, M. Collaborative Strategies in Wine Tourism: The Role of Local Networks. J. Wine Res. 2021, 32, 145–157. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, C.; Mota, S. Conservation and Wine: The Role of Biodiversity in Wine Tourism Development. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2022, 22, 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Atkin, T.; Gilinsky, A.; Newton, S.K. Sustainability in the wine industry: Altering the competitive landscape. In Proceedings of the 6th AWBR International Conference, Talence, France, 9–10 June 2011; Bordeaux Management School: Talence, France, 2011; pp. 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jezierska-Thole, A.; Biczkowski, M. Znaczenie i uwarunkowania innowacyjności w rolnictwie w Polsce. Rocz. Nauk. Stowarzyszenia Ekon. Rol. I Agrobiznesu 2013, 15, 124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias, M.P.; Navarro, M.M. Wine tourism development from the perspective of family winery. Cuad. Tur. 2014, 34, 415–418. [Google Scholar]

- Brito, C.; Pereira, S.; Martins, S.; Monteiro, A.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.M.; Dinis, L. Strategies for achieving the sustainable development goals across the wine chain: A review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1437872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Falcó, J.; Martínez-Falcó, J.; Marco-Lajara, B.; Sánchez-García, E.; Visser, G. Aligning the Sustainable development Goals in the wine industry: A bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilinsky, A., Jr.; Newton, S.K.; Vega, R.F. Sustainability in the global wine industry: Concepts and cases. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2016, 8, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Falcó, J.; Marco-Lajara, B.; Sánchez-García, E.; Zaragoza-Sáez, P. Wine Tourism as a Catalyst for the Sustainable Development Goals: The Case of Casa Sicilia Winery. In Sustainable International Business: Smart Strategies for Business and Society; Arte, P., Wang, Y., Dowie, C., Elo, M., Laasonen, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, C.; Cavicchi, A.; Casini, L. Sustainability in the wine industry: Key questions and research trends a. Agric. Food Econ. 2013, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presenza, A.; Minguzzi, A.; Petrillo, C. Managing wine tourism in Italy. J. Tour. Consum. Pract. 2010, 1, 46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Telfer, D.J. Strategic alliances along the Niagara wine route. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Mitchell, R. Wine Marketing; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2007; pp. 1–360. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan, L.; Alonso, A.D.; Scherrer, P. Wine tourism as a development initiative in rural Canary Island communities. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2009, 3, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, C.M.; Slave, C. The Wine Routes in France. In Proceedings of the 8th International Scientific Conference–ERAZ 2022 Conference Proceedings, Prague, Czech Republic, 26 May 2022; pp. 269–275. [Google Scholar]

- Titz, J.T. Pfälzerwald und Deutsche Weinstraße. Wandern & Einkehren: 50 Touren zwischen Kaiserslautern und dem Elsass. Mit GPS-Tracks; Bergverlag Rother: Oberhaching, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–216. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein, B. Verflechtungen zwischen Fremdenverkehr und Weinbau an der Deutschen Weinstraße; Ansatzpunkte einer eigenständigen Regionalentwicklung. Ansatzpunkte einer eigenständigen Regionalentwicklung. Selbstverl. d. Geograph. Ges. Trier.; 1996; pp. 1–337. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, R.; Cabral, J. 2022, Digital marketing strategies in the wine tourism sector: A case study of Portugal. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 43, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsauer, C.M. Das Naturraumpotential in der Region der Südlichen Weinstraße und Seine Auswirkungen auf den Tourismus/Vorgelegt von Carina Ramsauer. Master’s Thesis, Universität Graz, Österreich, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, H.; Leung, X.Y. Virtual wine tours and wine tasting: The influence of offline and online embodiment integration on wine purchase decisions. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83, 104250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarrita-Cascante, D.; Brennan, M.A.; Luloff, A.E. Community agency and sustainable tourism development: The case of La Fortuna, Costa Rica. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 735–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, P.; Silva, A.; Costa, A. Sustainability in wine tourism: The case of Portuguese wineries. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 23, 773–784. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, J.A.; Grätsch, S.D.; Karremann, M.K.; Jones, G.V.; Pinto, J.G. Ensemble projections for wine production in the Douro Valley of Portugal. Clim. Change 2013, 117, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oltean, F.D.; Gabor, M.R. Wine tourism—A sustainable management tool for rural development and vineyards: Cross-cultural analysis of the consumer profile from Romania and Moldova. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodfield, P.J.; Shepherd, D.; Woods, C. How can family winegrowing businesses be sustained across generations? Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2017, 29, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberto, D.; Sousa, B.; Paiga, H.; Liberato, P. Exploring Wine Tourism And Competitiveness Trends: Insights From Portuguese Context Enoturismo E Tendências De Competitividade: Perspetivas Do Contexto Português. E-Rev. De Estud. Intercult. 2023, 11, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen, C.; Sgubin, G.; Bois, B.; Ollat, N.; Swingedouw, D.; Zito, S.; Gambetta, G.A. Climate change impacts and adaptations of wine production. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.I.; Cunha, R.; Matos, O.; Fernandes, C. Wine tourism experiences and marketing: The case of the Douro valley in Portugal. In Wine Tourism Destination Management and Marketing: Theory and Cases; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 203–220. [Google Scholar]

- Jezierska-Thöle, A. Development of Rural Areas of Northern and Western Poland and Eastern Germany; Scientific Publishing House of the Nicolaus Copernicus University: Toruń, Poland, 2018; pp. 1–555. [Google Scholar]

- Mazurkiewicz-Pizło, A.; Pizło, M. Turystyka winiarska w Portugalii–studium przypadku winnicy Quinta da Pacheca w regionie Douro. Tur. Kult. 2024, 3, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voluntary National Reviews: Synthesis Compilation (UN, 2018)|Education Within the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [Online]. Available online: www.sdg4education2030.org (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Quintela, J.A.; Albuquerque, H.; Freitas, I. Port Wine and Wine Tourism: The Touristic Dimension of Douro’s Landscape. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamowicz, M.; Gawrońska, M. Produkt turystyczny jako wyraz tradycji i kultury regionu na przykładzie wina porto i muzyki fado-narodowych produktów turystycznych Portugalii. Stud. Ekon. I Reg. 2012, 5, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk, A. Szlaki wina—Nowa forma aktywizacji turystycznej obszarów wiejskich. Pr. I Stud. Geogr. 2003, 32, 69–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk, A. Turystyka winiarska. In Turystyka Zrównoważona; Kowalczyk, A., Ed.; PWN: Polska, Poland, 2010; pp. 208–230. [Google Scholar]

- Biczkowski, M.; Jezierska-Thöle, A.; Rudnicki, R. The impact of rdp measures on the diversification of agriculture and rural development—Seeking additional livelihoods: The case of Poland. Agriculture 2021, 11, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alebaki, M.; Iakovidou, O. Market segmentation in wine tourism: A comparison of approaches. Tourismos 2011, 6, 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Alant, K.; Bruwer, J. Wine tourism behaviour in the context of a motivational framework for wine regions and cellar doors. J. Wine Res. 2004, 1, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telfer, D.J. The Northeast Wine Route: Wine tourism in Ontario, Canada and in New York State. In Wine Tourism Around the World. Development, Management and Markets; Hall, C.M., Sharples, L., Cambourne, B., Macionis, N., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2000; pp. 253–271. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D.; Brown, G. Critical success factors for wine tourism regions: A demand analysis. Tour. Manag. 2006, 1, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço-Gomes, L.; Pinto, L.M.; Rebelo, J. Wine and cultural heritage. The experience of the Alto Douro Wine Region. Wine Econ. Policy 2015, 4, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Livat, F.; Ye, S. Effects of terrorist attacks on tourist flows to France: Is wine tourism a substitute for urban tourism? J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 14, 100385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drappier, J.; Thibon, C.; Rabot, A.; Geny-Denis, L. Relationship between wine composition and temperature: Impact on Bordeaux wine typicity in the context of global warming. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertzberg, A.; Malorgio, G. Wine demand in Italy: An analysis of consumer preferences. New Medit. 2008, 7, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bijak, U. Zamiast toastu: Kilka uwag o bułgarskim winie/Instead of a Toast: A Few Remarks on Bulgarian Wine. Onomastica 2016, 60, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, P.A.; Dans, E.P. The ‘terroirist’ social movement: The reawakening of wine culture in Spain. J. Rural. Stud. 2018, 61, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varsei, M.; Polyakovskiy, S. Sustainable supply chain network design: A case of the wine industry in Australia. Omega 2017, 66, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, N. Turystyka winiarska w Kolumbii Brytyjskiej w Kanadzie. Ann. Univ. Paedagog. Cracoviensis Stud. Geogr. 2021, 16, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkin, T.; Gilinsky, A., Jr.; Newton, S.K. Environmental strategy: Does it lead to competitive advantage in the US wine industry? Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2012, 24, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.portugalvineyards.com/pt/caixas-mistas/9329-the-douro-a-selection-of-12x-premium-wines (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Adão, F.; Fraga, H.; Fonseca, A.; Malheiro, A.C.; Santos, J.A. The Relationship between Land Surface Temperature and Air Temperature in the Douro Demarcated Region, Portugal. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Population Indicators by Municipality, 2022; Regional Statistical Yearbooks—2022; Tourism Activity Indicators by Municipality. 2022. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_base_dados (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Fura, B.; Wang, Q. The level of socioeconomic development of EU countries and the state of ISO 14001 certification. Qual. Quant. 2017, 51, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defert, P. Le Taut de FonctionTouristique: Mise au point et critique. Les Cah. Du Tour. Ser.-C 1967, 5, 110–122. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, I.M.; Khan, M.A.; Yasmin, M.; Shah, J.H.; Gabryel, M.; Scherer, R.; Damaševičius, R. Pearson correlation-based feature selection for document classification using balanced training. Sensors 2020, 20, 6793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, E.; Bruwer, J. Wine Tourism Preferences: Developing the Wine Tourism Offer in the Loire Valley. In Proceedings of the 7th AWBR International Conference, Bordeaux, France, 12–15 June 2013; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer, A. Wine plus tourism offers: It is not all about wine—Wine tourism in Germany. In Wine Tourism Destination Management and Marketing: Theory and Cases; Sigala, M., Richard, N.S., Robinson, Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 399–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.; Barattucci, M.; Tavares, F.O.; Tavares, V.C. The Senses as Experiences in Wine Tourism—A Comparative Statistical Analysis between Abruzzo and Douro. Heritage 2023, 6, 5672–5688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzo-Navarro, M.; Pedraja-Iglesias, M. Wine tourism development from the perspective of the potential tourist in Spain. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 21, 816–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cujbă, V.; Sîrbu, R. Cricova–the national and international tourist brand of the Republic of Moldova. Sport Tour. Cent. Eur. J. 2020, 3, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, B.E.; Rotarou, E.S. Challenges and opportunities for the sustainable development of the wine tourism sector in Chile. J. Wine Res. 2018, 29, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subject of Study | Source |

|---|---|

| Wine tourism behaviour | [9,11,14,17,27,30,35,37,47] |

| Wine market | [9,22,27,37,48,49] |

| Environmental concerns | [5,13,38] |

| Marketing wine | [22,27,37] |

| Critical success factors for wine tourism | [9,11,30] |

| Local development | [2,4,8,14,15,18,33,38,48,49] |

| Sustainable tourism | [7,15,16,18,33,40,48] |

| Douro Wine Region | Tourist Attractions |

|---|---|

| Porto | - Porto—the most beautiful section of the river. - Amarante—located on a tributary of the Rio Tâmega, the most attractive town in the region. - Livração—railroad station, 60 km from Porto, Verde wine production. |

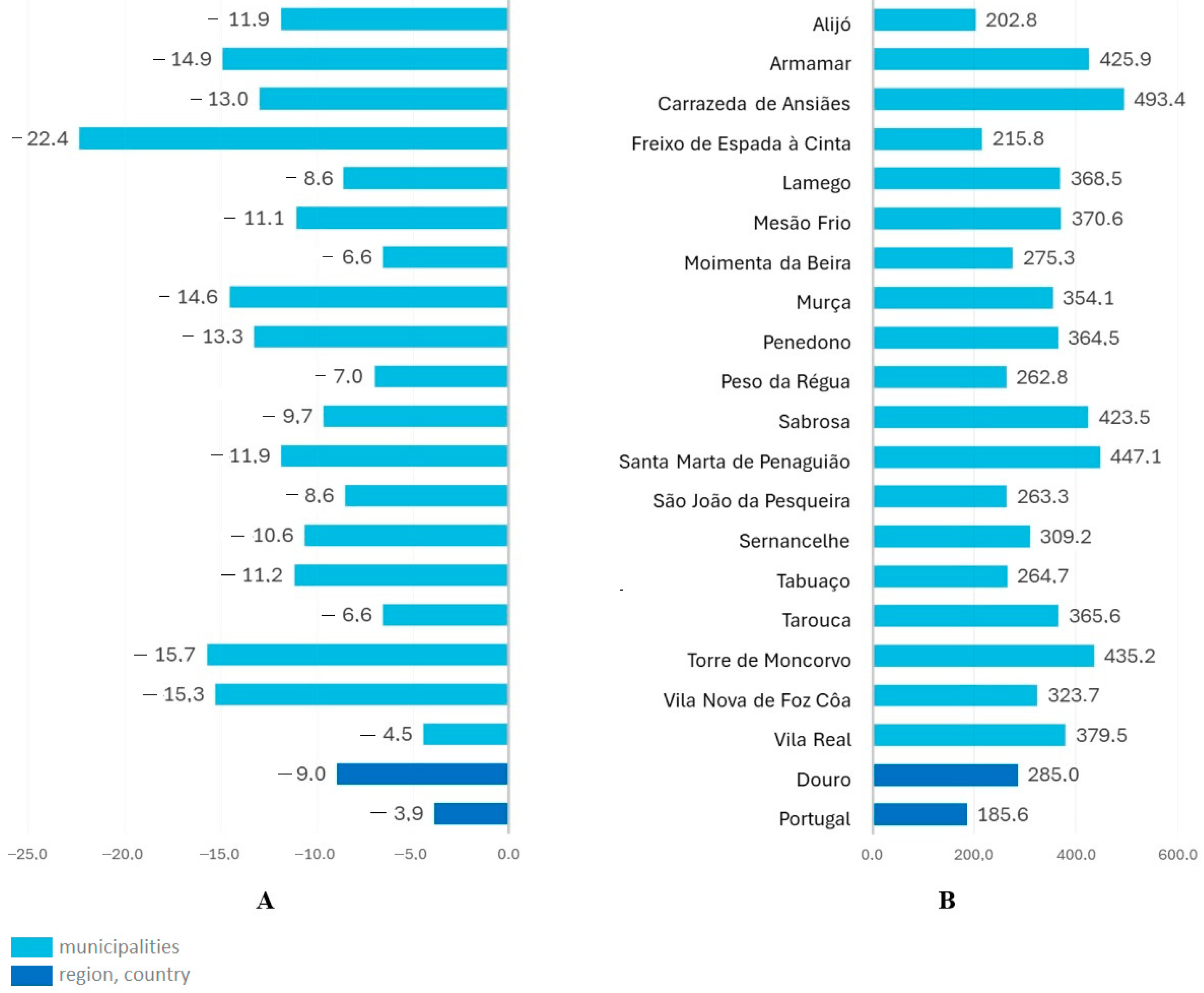

| Baixo Corgo (Lower Corgo) | - Peso da Régua—the capital of the Alto Douro province, a port wine-trading town (since the 18th century), the centre of cruises to Pinhão, and the starting station of the Corgo to Vila Real railroad in Trás-os-Montes. - Museu do Douro, housed in a converted warehouse on the river. The town is surrounded by terraced hills covered with vines. - Lamego—a pilgrimage town, Lamego Castle, and Lamego Cathedral. - Peso da Régua, São Leonardo in Galafura, and Santo António do Loureiro—the most beautiful viewpoints. - Wine production: Vinho white Porto, DOC Douro, Raposeira—a Portuguese wine resembling champagne. |

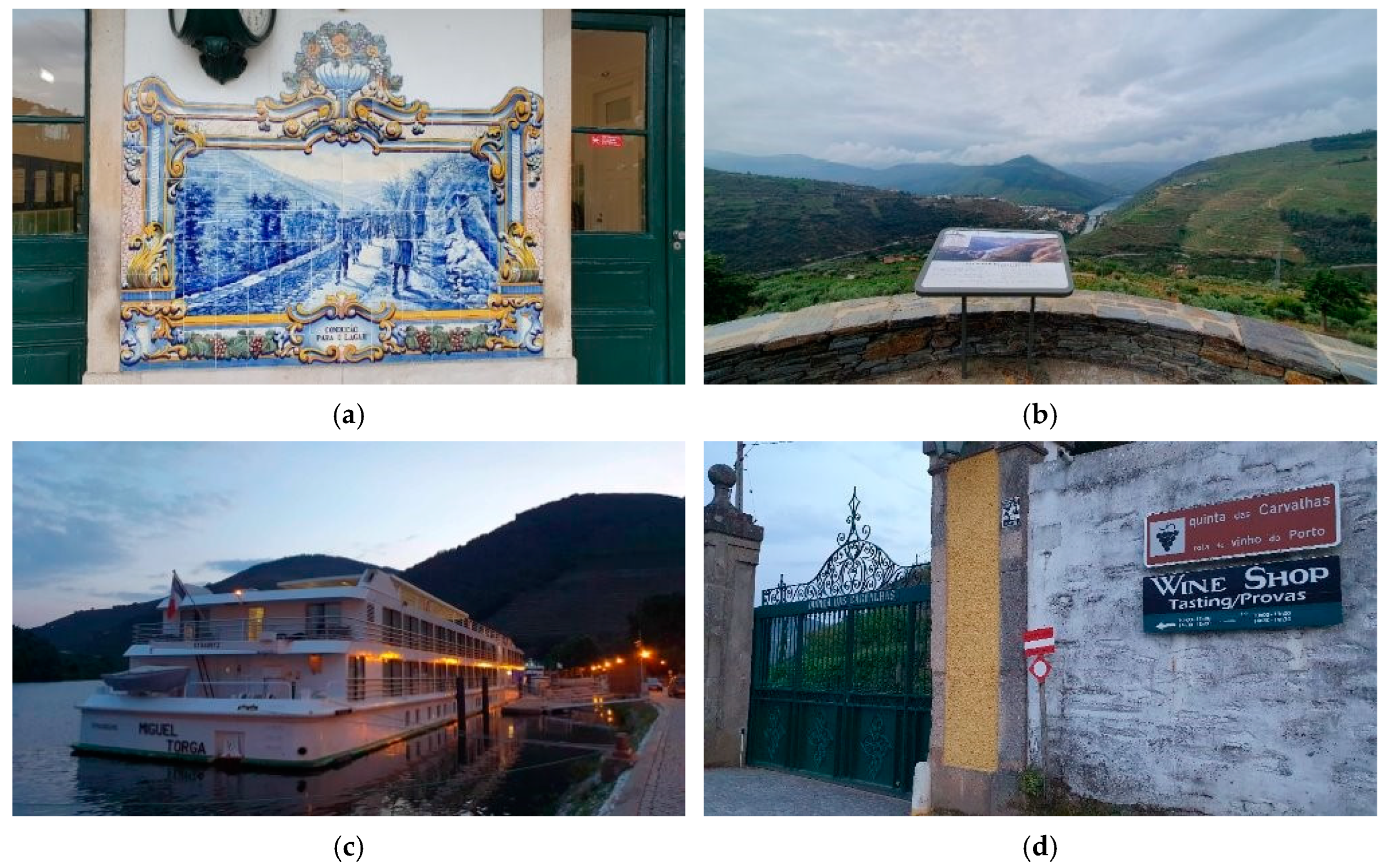

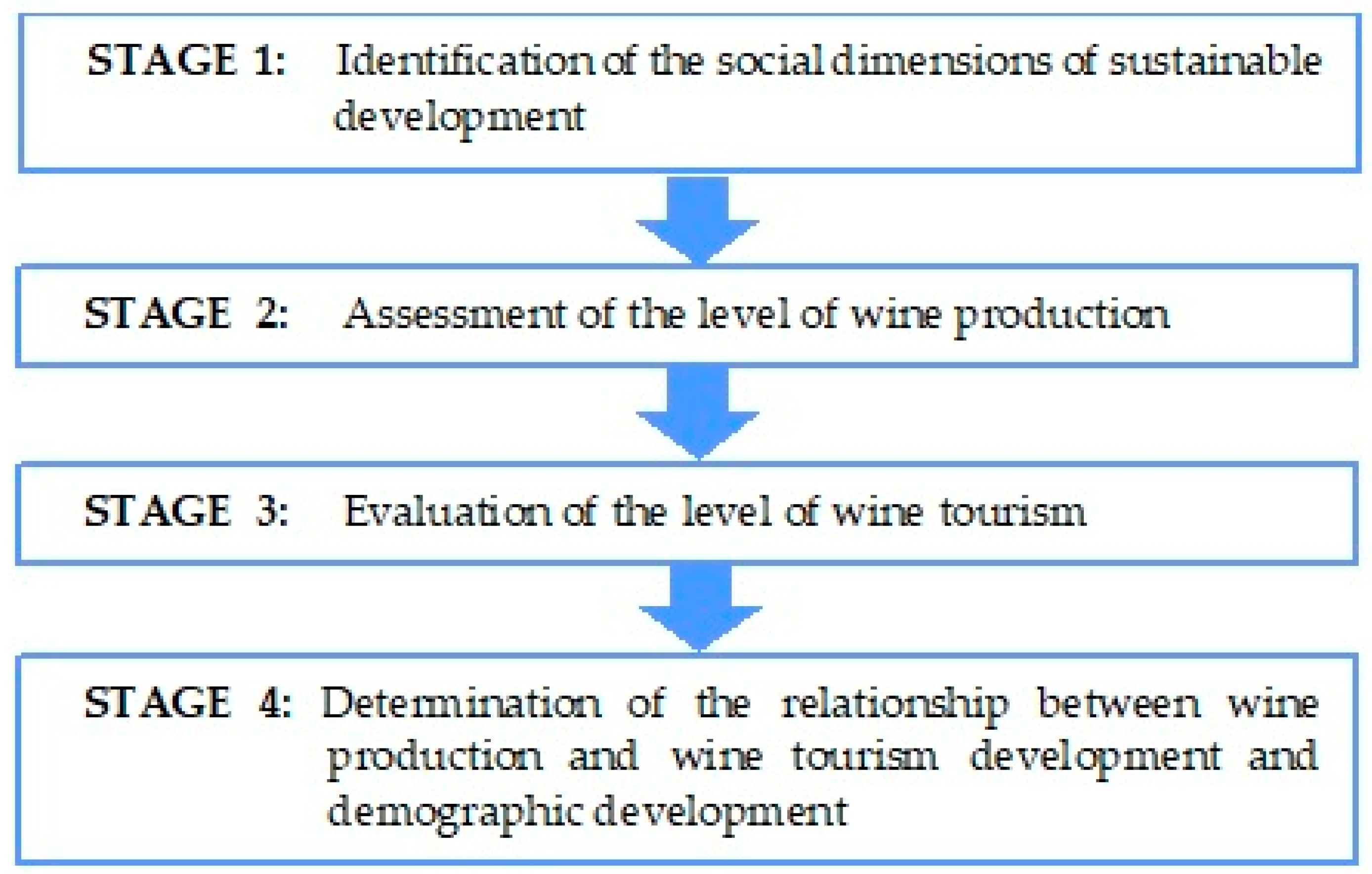

| Alto Corgo | - Pinhão—the Douro Valley’s most beautiful town, located 25 km upstream from Peso da Régua, surrounded by terraced vineyards, and with a historic train station decorated with traditional blue and white azulejo tiles depicting scenes from the region’s history and culture; Douro Valley Tourist Centre in Pinhão offers hiking, cycling, and canoeing. - The region’s cuisine—cozido, a hearty stew of meat and vegetables, and bacalhau, a dish of salted cod. - Tua—a charming village for hiking, with a scenic riverside path leading to Tua Dam. |

| Douro Superior | - Douro Superior—a mountainous landscape at the Valeira dam. The mountains block half of the rain coming in from the Atlantic, leaving the region much drier than other regions, which led to the name Terra Quente or hot lands. - Vila Nova de Foz Côa—Parque Arqueológico do Vale do Côa,—Paleolithic art, 30,000 years old. - Miranda do Douro—a fortified town located on the edge of the Río Douro canyon, known as a fortress in the ‘wild east’, with a town castle and 16th-century cathedral. |

| Diagnostic Indicators | Type |

|---|---|

| Population density | Stimulant |

| Natural increase per 1000 population | Stimulant |

| Population aging rate * | Destimulant |

| Feminization index | Stimulant |

| Class | Separation Criterion | Level of Demographic Potential |

|---|---|---|

| I | High | |

| II | Medium-high | |

| III | Medium-low | |

| IV | Low |

| Class | Charvat Index | Schneider Index | Level of Development of the Tourism Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | >500 | >300 | High |

| II | 351–500 | 300–200 | Medium-high |

| III | 201–350 | 200–100 | Medium-low |

| IV | 0–200 | 0–100 | Low |

| Correlation Relationship | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| r ≥ 0.9 | Very strong dependence |

| 0.7–0.9 | Moderate dependence |

| 0.7–0.9 | Fairly strong dependence |

| 0.4–0.7 | Moderate dependence |

| 0.2–0.4 | Weak relationship |

| r ≤ 0.2 | No linear relationship |

| Country/Region/Municipality | Population Density | Birth Rate | Deaths |

|---|---|---|---|

| No./km2 | No./1000 Population | No./1000 Population | |

| Portugal | 113 | 8 | 11.9 |

| Douro | 45 | 5.8 | 14.8 |

| Alijó | 35 | 5.4 | 17.2 |

| Armamar | 49 | 4.6 | 19.4 |

| Carrazeda de Ansiães | 19 | 4.6 | 17.6 |

| Freixo de Espada à Cinta | 13 | 6.3 | 28.5 |

| Lamego | 146 | 5.3 | 13.9 |

| Mesão Frio | 132 | 4.8 | 15.9 |

| Moimenta da Beira | 44 | 7.0 | 13.6 |

| Murça | 27 | 3.1 | 17.6 |

| Penedono | 21 | 5.4 | 18.6 |

| Peso da Regua | 152 | 5.9 | 12.9 |

| Sabrosa | 36 | 6.1 | 15.8 |

| Santa Marta de Penaguião | 86 | 4.2 | 16.0 |

| São João da Pesqueira | 25 | 6.0 | 14.6 |

| Sernancelhe | 25 | 4.2 | 14.9 |

| Tabuaço | 37 | 6.0 | 17.1 |

| Tarouca | 74 | 5.0 | 11.6 |

| Torre de Moncorvo | 13 | 5.5 | 21.2 |

| Vila Nova de Foz Côa | 16 | 5.1 | 20.3 |

| Vila Real | 131 | 7.1 | 11.6 |

| Region/LAU | Population Indicators | Level of Development |

|---|---|---|

| Tarouca | 0.485 | I |

| Vila Real | 0.477 | I |

| Lamego | 0.436 | I |

| Peso da Régua | 0.412 | I |

| São João da Pesqueira | 0.403 | I |

| Mesão Frio | 0.313 | II |

| Moimenta da Beira | 0.301 | II |

| Santa Marta de Penaguião | 0.249 | II |

| Alijó | 0.235 | II |

| Sernancelhe | 0.212 | II |

| Sabrosa | 0.189 | III |

| Tabuaço | 0.097 | III |

| Carrazeda de Ansiães | 0.081 | III |

| Armamar | 0.067 | III |

| Murça | 0.056 | III |

| Penedono | 0.041 | III |

| Vila Nova de Foz Côa | 0.007 | IV |

| Freixo de Espada à Cinta | −0.066 | IV |

| Torre de Moncorvo | −0.075 | IV |

| Area | Total | Liqueur Wine by Protected Designation of Origin | Wine by Protected Designation of Origin | Wine by Protected Geographical Indication | Wines Without Certification | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Red/Rose | White | Red/Rose | White | Red/Rose | |||

| Portugal [L] | 6,660,134 | 717,278 | 1,376,668 | 1,650,907 | 639,329 | 1,722,561 | 149,934 | 403,460 |

| Douro [L] | 129,152 | 655,405 | 170,132 | 395,225 | 3434 | 3633 | 21,515 | 42,179 |

| Douro Portugal = 100% | 19.7 | 91.4 | 12.4 | 24.0 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 14.3 | 10.4 |

| Douro [%] | 100 | 50.7 | 13.2 | 30.6 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 3.3 |

| Region/LAU | Total | Liqueur | White Wine by Protected Designation of Origin | Red/Rose Wine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Douro | 1,291,521 | 50 | 13 | 30 |

| Vila Real | 102,449 | 33 | 24 | 34 |

| Vila Nova de Foz Côa | 112,623 | 46 | 8 | 44 |

| Torre de Moncorvo | 14,873 | 64 | 7 | 28 |

| Tarouca | 9695 | 0 | 37 | 43 |

| Tabuaço | 53,473 | 59 | 10 | 30 |

| Sernancelhe | 380 | 0 | 13 | 28 |

| São João da Pesqueira | 162,476 | 55 | 8 | 31 |

| Santa Marta de Penaguião | 92,118 | 53 | 8 | 37 |

| Sabrosa | 89,733 | 46 | 14 | 35 |

| Peso da Régua | 77,985 | 37 | 17 | 42 |

| Penedono | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Murça | 29,603 | 35 | 8 | 28 |

| Moimenta da Beira | 26,461 | 0 | 32 | 23 |

| Mesão Frio | 22,250 | 42 | 14 | 39 |

| Lamego | 217,980 | 63 | 9 | 22 |

| Freixo de Espada à Cinta | 18,984 | 50 | 14 | 26 |

| Carrazeda de Ansiães | 32,612 | 87 | 3 | 7 |

| Armamar | 20,485 | 14 | 24 | 28 |

| Alijó | 207,341 | 56 | 17 | 22 |

| Area | Total | Hotel Establishments | Local Accommodation | Tourism in Rural Areas and Lodging Tourism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guests | 353,985 | 181,450 | 37,176 | 135,359 |

| [%] | 100 | 51.3 | 10.5 | 38.2 |

| Nights | 589,456 | 300,729 | 66,202 | 222,525 |

| [%] | 100 | 51.0 | 11.2 | 37.8 |

| Revenue from accommodation | 47,925 | 28,001 | 3378 | 16,547 |

| [%] | 100 | 58.4 | 7.0 | 34.5 |

| Region/LAU | Level of Demographic Development | Level of Tourist Development (Charvat Index) | Intensity of Tourist Traffic (Schneider Index) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tarouca | I | 197 | 129 |

| Vila Real | I | 144 | 90 |

| Lamego | I | 665 | 385 |

| Peso da Régua | I | 473 | 288 |

| São João da Pesqueira | I | 257 | 143 |

| Mesão Frio | II | 805 | 485 |

| Moimenta da Beira | II | 51 | 33 |

| Santa Marta de Penaguião | II | 261 | 159 |

| Alijó | II | 439 | 271 |

| Sernancelhe | II | 213 | 126 |

| Sabrosa | III | 566 | 321 |

| Tabuaço | III | 562 | 360 |

| Carrazeda de Ansiães | III | 264 | 151 |

| Armamar | III | 507 | 285 |

| Murça | III | 66 | 14 |

| Penedono | III | 53 | 48 |

| Vila Nova de Foz Côa | IV | 191 | 118 |

| Freixo de Espada à Cinta | IV | 562 | 378 |

| Torre de Moncorvo | IV | 194 | 130 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jezierska-Thöle, A.; Gonia, A.; Podgórski, Z.; Gwiaździńska-Goraj, M. Wine Tourism as a Tool for Sustainable Development of the Cultural Landscape—A Case Study of Douro Wine Region in Portugal. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041494

Jezierska-Thöle A, Gonia A, Podgórski Z, Gwiaździńska-Goraj M. Wine Tourism as a Tool for Sustainable Development of the Cultural Landscape—A Case Study of Douro Wine Region in Portugal. Sustainability. 2025; 17(4):1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041494

Chicago/Turabian StyleJezierska-Thöle, Aleksandra, Alicja Gonia, Zbigniew Podgórski, and Marta Gwiaździńska-Goraj. 2025. "Wine Tourism as a Tool for Sustainable Development of the Cultural Landscape—A Case Study of Douro Wine Region in Portugal" Sustainability 17, no. 4: 1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041494

APA StyleJezierska-Thöle, A., Gonia, A., Podgórski, Z., & Gwiaździńska-Goraj, M. (2025). Wine Tourism as a Tool for Sustainable Development of the Cultural Landscape—A Case Study of Douro Wine Region in Portugal. Sustainability, 17(4), 1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041494