The Effect of Work–Family Facilitation on Employee Proactive Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Relationship Between Work–Family Facilitation and Employee Proactive Behavior

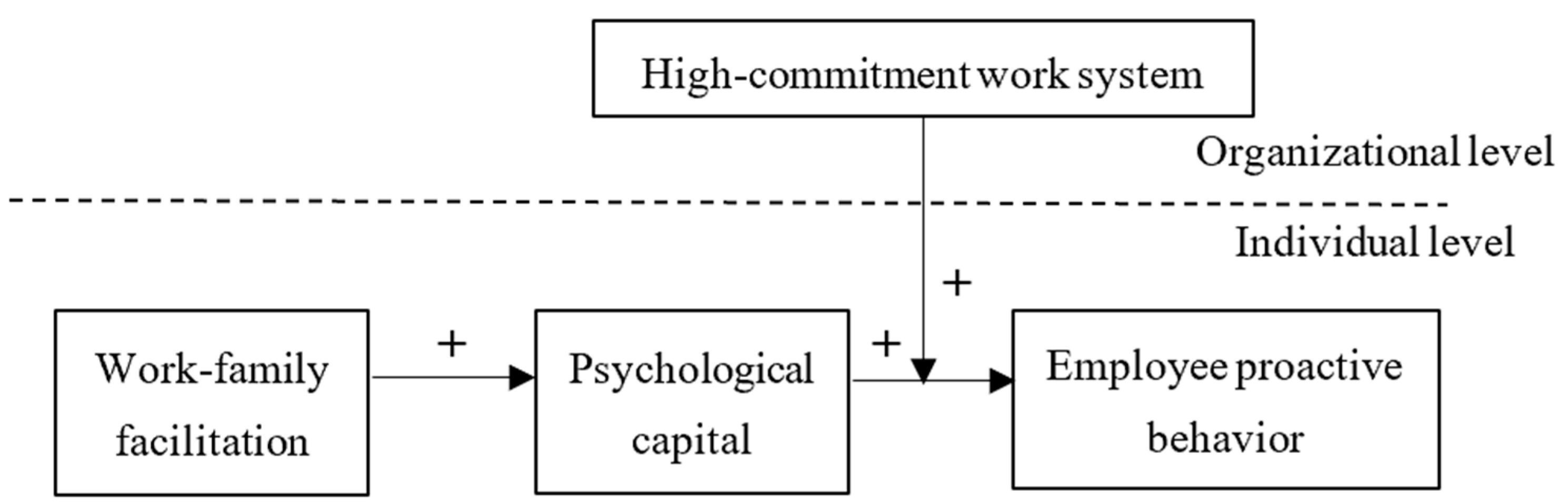

2.2. Mediating Role of Psychological Capital

2.3. The Regulating Role of the High-Commitment Work System

2.4. The Role of Regulated Intermediaries

3. Research Design

3.1. Research Sample

3.1.1. Pre-Research Stage

3.1.2. Formal Research Stage

3.2. Measurement of Variables

3.2.1. Work–Family Facilitation (WFF)

3.2.2. Proactive Behavior (PB)

3.2.3. Psychological Capital (PC)

3.2.4. High-Commitment Work System (HCWS)

3.3. Control Variables

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

4.2. Correlation Analysis

4.3. Validity Tests

4.4. Null Model Test

4.5. Hypothesis Testing

4.5.1. Tests for Main Effects

4.5.2. Intermediation Tests

4.5.3. Tests of Regulation

4.5.4. Testing of Moderated Mediation Effect

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Management Insights

5.3. Limitations and Prospects for Future Research

5.4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Griffin, M.A.; Neal, A.; Parker, S.K. A new model of work role performance: Positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Jiang, R. Perceived insider status and innovative behaviour of the new generation of employees: Mediating effect of innovative self-efficacy and moderation of group competitive climate. J. Psychol. Afr. 2024, 34, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.M.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Y.X. A Review on the Past 100 Years of Human Resource Management: Evolution and Development. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2019, 41, 50–73. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, C.; Mónico, L.; Pinto, A.; Oliveira, S.; Leite, E. Effects of work–family conflict and facilitation profiles on work engagement. Societies 2024, 14, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eason, D.; Weerakit, N. Effects of Work-Family Conflict and Work-Family Facilitation on Employee Burnout during COVID-19 in the Thai Hotel Industry. J. Behav. Sci. 2023, 18, 32–48. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, R.H.; Miao, C.; Silard, A. Work–family enrichment: Prospects for enhancing research. In Emotion in Organizations: A Coat of Many Colors; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2024; pp. 155–178. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Zhao, S.M.; Su, X.S.; Liu, S. The Influence of CEO Humble Leadership on Employee Proactive Behavior: A Cross Level Research. East China Econ. Manag. 2023, 37, 110–119. [Google Scholar]

- Han, M.; Zhang, M.; Hu, E.; Shan, H. Fueling employee proactive behavior: The distinctive role of Chinese enterprise union practices from a conservation of resources perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2024, 34, 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, P. Measuring the impact of learning organization on proactive work behavior: Mediating role of employee resilience. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2023, 15, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Chen, H. The effects of directionality and asymmetry of interpenetration between work and non-work boundaries on job burnout. Econ. Jingwei 2020, 37, 132–139. [Google Scholar]

- Soelton, M. How Did It Happen: Organizational Commitment and Work-Life Balance Affect Organizational Citizenship Behavior. JDM (J. Din. Manaj.) 2023, 14, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basinska, B.A.; Rozkwitalska, M.J.C.P. Psychological capital and happiness at work: The mediating role of employee thriving in multinational corporations. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emur, A.P.; Mufidawati, H.; Andryadi, M.F.; Pusparini, E.S.; Rachmawati, R. The Role of Psychological Capital on the Effect of High-Performance Work System and Proactive Personality on Job Performance. J. Manaj. Teor. Dan Terap. 2023, 16, 636–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, D.; Strauss, K.; Schwake, C.; Urbach, T. Creating meaning by taking initiative: Proactive work behavior fosters work meaningfulness. Appl. Psychol. 2023, 72, 506–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.T.; Li, R. Content structure and measurement of corporate high-performance work system. Manag. World 2015, 31, 100–116. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, F.Q.; Luo, K.; Zhang, G.L. The effect of work-family relationship on job performance: A cross-over view or a matching view?---Evidence from meta-analysis. China Hum. Resour. Dev. 2017, 31, 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.P.; Liao, J.Q. Exploring the New Progress of Research on Employee Initiative Behavior in Foreign Countries. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2011, 33, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.Q.; Zhang, B. New tendency of work-family relationship research A review of work-family promotion research. Bus. Cult. 2012, 6, 371–373. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.L.; Long, L.R.; Zhu, Q.Q. Seeking change with one mind: A study of the influence mechanism of participative leadership on employees’ proactive change behavior. Forecasting 2015, 34, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Fay, D.; Hüttges, A. Drawbacks of proactivity: Effects of daily proactivity on daily salivary cortisol and subjective well-being. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.Q.; Li, Y.J.; Wang, L.P. Research on the Relationship between Job Happiness and Employee Innovation Performance. J. Yunnan Univ. Financ. Econ. 2023, 39, 98–110. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Hou, Q.; Xue, Z.; Li, H. Why employees engage in proactive career behavior: Examining the role of family motivation. Career Dev. Int. 2024, 29, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Cheng, S. Comparative analysis of international and domestic psychological capital research based on knowledge mapping. Psychol. Res. 2023, 43, 343–353. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.Y.; Kong, Y. Value-added research on modern human resource management based on the perspective of psychological capital theory. East China Econ. Manag. 2019, 33, 154–159. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F.; Luthans, K.W.; Luthans, B.C. Positive psychological capital: Beyond human and social capital. Bus. Horiz. 2004, 47, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruman, J.A.; Saks, A.M. Organizational socialization and newcomers’ psychological capital and well-being. In Advances in Positive Organizational Psychology; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2013; pp. 211–236. [Google Scholar]

- Ten Brummelhuis, L.L.; Bakker, A.B. A resource perspective on the work-home interface: The work-home resources model. Am. Psychol. 2012, 67, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.M.; Zhu, B.; Du, J.H.; Li, Y.X. The relationship between work-family promotion and career success among corporate employees: The mediating role of psychological capital. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 28, 181–184+86. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, S.; Ahmadi Malek, F.; Yaghoubi Farani, A.; Liobikienė, G. The role of transformational leadership in developing innovative work behaviors: The mediating role of employees’ psychological capital. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M.; Avolio, B.J. Psychological Capital: Developing the Human Capital Edge; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Reivich, K.; Shatte, A. The Resilience Factor: 7 Keys to Finding Your Inner Strength and Overcoming Life’s Hurdles; Harmony: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, C.J. Speech perception in the presence of other sounds. Acoust. Soc. Am. J. 2005, 117, 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.R. Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychol. Inq. 2002, 13, 249–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.E.; Darke, P.R. The optimistic trust effect: Use of belief in a just world to cope with decision-generated threat. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallknecht, D.E.; Brown, J.D. Tenacity of avian influenza viruses. Rev. Sci. ET Tech.-Off. Int. Des Epizoot. 2009, 28, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, B.; Adalgisa, B.; Isabella, M.; Salanova, M. Psychological Capital, Autonomous Motivation and Innovative Behavior: A Study Aimed at Employees in Social Networks. Psychol. Rep. 2023; OnlineFirst. [Google Scholar]

- Irfan, U.; Mazhar, R.H.; Abid, M. The impact of proactive personality and psychological capital on innovative work behavior: Evidence from software houses of Pakistan. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2024, 27, 1967–1985. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.Q.; Jiang, X.; Li, D. A study of the impact of perceived organizational craftsmanship on employees’ proactive innovation behavior: The role of work passion and perfectionism. China Hum. Resour. Dev. 2024, 41, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Y.; Huang, J.C.; Farh, J.L. Employee learning orientation, transformational leadership, and employee creativity: The mediating role of employee creative self-efficacy. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilag, O.K.T.; Tiongzon, B.D.; Paragoso, S.D.; Ompad, E.A.; Bibon, M.B.; Alvez, G.G.T.; Sasan, J.M. High Commitment Work System and Distributive Leadership on Employee Productive Behavior. Gospod. Innow. 2023, 36, 389–409. [Google Scholar]

- Hom, P.W.; Tsui, A.S.; Wu, J.B.; Lee, T.W.; Zhang, A.Y.; Fu, P.P.; Li, L. Explaining employment relationships with social exchange and job embeddedness. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X. How do high-commitment work systems stimulate employees’ creative behavior? A multilevel moderated A multilevel moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 904174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Zhao, S.M.; Fan, L.J. Psychological Need Satisfaction Contributes to Employees’ Proactive Behavior?—The moderating role of self-efficacy. Res. Financ. Issues 2018, 40, 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz, J.G.; Marks, N.F. Family, work, work-family spillover, and problem drinking during midlife. J. Marriage Fam. 2000, 62, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Tsui, A.S. When brokers may not work: The cultural contingency of social capital in Chinese high-tech firms. Adm. Sci. Q. 2007, 52, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirak, R.; Peng, A.C.; Carmeli, A.; Schaubroeck, J.M. Linking leader inclusiveness to work unit performance: The importance of psychological safety and learning from failures. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhao, D.D.; Zhang, R.J.; Liu, X.J. A study on the relationship between work without boundaries and employees’ proactive behavior in distributed office. China Hum. Resour. Dev. 2024, 41, 6–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.L.; Xia, F.B. Theoretical Integration and Model Reconstruction of Work-Family Relationship. Res. Financ. Issues 2017, 39, 138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill, K.E.; Giandrea, M.D.; Quinn, J.F. Retirement patterns from career employment. Gerontologist 2006, 46, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | SD | Gender | Age | Education | Tenure | WFF | PC | HCWS | PB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1.451 | 0.498 | 1 | |||||||

| Age | 3.753 | 1.457 | −0.113 *** | 1 | ||||||

| Education | 2.937 | 1.161 | −0.021 | −0.237 *** | 1 | |||||

| Tenure | 3.719 | 1.085 | −0.044 | 0.545 *** | −0.209 *** | 1 | ||||

| WFF | 3.986 | 1.366 | −0.045 | 0.086 ** | −0.011 | 0.016 | 1 | |||

| PC | 5.167 | 0.992 | −0.025 | −0.003 | −0.014 | −0.050 | 0.265 *** | 1 | ||

| HCWS | 4.908 | 1.016 | −0.048 | 0.012 | 0.107 *** | 0.013 | 0.079 ** | 0.048 | 1 | |

| PB | 5.495 | 1.058 | 0.003 | 0.052 | −0.074 ** | 0.008 | 0.225 *** | 0.606 *** | 0.059 * | 1 |

| Constructs | Items | Factor Loadings | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work–family facilitation | 1. The things I do at work help me deal with personal and family matters. | 0.599 | 0.832 | 0.554 |

| 2. The skills I have gained at work benefit me in accomplishing things at home. | 0.878 | |||

| 3. I achieve things at work that make me funnier and happier in my family. | 0.855 | |||

| 4. Because of my work, I have more energy to take care of things in my family. | 0.716 | |||

| Psychological capital | 1. I am confident that I can analyze long-term problems and find solutions to them. | 0.722 | 0.908 | 0.599 |

| 2. I am confident in presenting things within my scope of work in meetings with management. | 0.673 | |||

| 3. I believe I can contribute to the discussion of the company’s strategy. | 0.648 | |||

| 4. I believe I can help to set goals within my area of work. | 0.62 | |||

| 5. I am confident that I can contact and discuss issues with people outside the company (e.g., customers, suppliers, etc.). | 0.85 | |||

| 6. I believe that I can present information to some of my coworkers. | 0.861 | |||

| 7. If I find myself in a difficult situation at work, I can think of a number of ways to get out of it. | 0.839 | |||

| 8. Currently, I am fulfilling my work objectives to the fullest extent possible. | 0.855 | |||

| 9. There are many solutions to any problem. | 0.85 | |||

| 10. Currently, I consider myself to be quite successful at my job. | 0.593 | |||

| 11. I can think of many ways to achieve my current work goals. | 0.768 | |||

| 12. Currently, I am achieving the work goals I have set for myself. | 0.512 | |||

| 13. When I have a setback at work, it is difficult for me to recover from it and move forward. | 0.619 | |||

| 14. At work, I try to solve problems no matter what. | 0.676 | |||

| 15. At work, if I have to do it, so to speak, I can handle it alone. | 0.597 | |||

| 16. I am usually comfortable with stress at work. | 0.512 | |||

| 17. I am able to get through difficult times at work because I have been through a lot before. | 0.542 | |||

| 18. In my current job, I feel like I can handle a lot of things at once. | 0.562 | |||

| 19. In my job, I usually hope for the best when I am not sure about something. | 0.580 | |||

| 20. If something is going to go wrong, it will go wrong even if I work wisely. | 0.624 | |||

| 21. I always look on the bright side of things when it comes to my work. | 0.632 | |||

| 22. I am optimistic about what will happen to my job in the future. | 0.617 | |||

| 23. In my current job, things never go the way I want them to go. | 0.629 | |||

| 24. At work, I always believe that “there is light behind the darkness, no need to be pessimistic”. | 0.524 | |||

| Employee proactive behavior | 1. I take the initiative to solve problems. | 0.805 | 0.932 | 0.662 |

| 2. Whenever a problem arises, I look for a solution immediately. | 0.822 | |||

| 3. I will take the opportunity to be active whenever it arises. | 0.845 | |||

| 4. I will take the initiative immediately, even when others do not. | 0.839 | |||

| 5. I am quick to seize opportunities to achieve goals. | 0.844 | |||

| 6. I usually do more than is required of me. | 0.807 | |||

| 7. I am particularly good at realizing ideas. | 0.737 | |||

| High-commitment work system | 1. Promoting from within rather than recruiting from the outside. | 0.571 | 0.913 | 0.497 |

| 2. There is a careful selection process when recruiting employees. | 0.539 | |||

| 3. The company has a lot of training. | 0.624 | |||

| 4. The company organizes a lot of activities. | 0.608 | |||

| 5. Do not easily dismiss employees. | 0.585 | |||

| 6. Employees work in a wide range of fields. | 0.617 | |||

| 7. Employees are widely rotated within the organization. | 0.702 | |||

| 8. Performance appraisals emphasize team performance rather than individual performance. | 0.679 | |||

| 9. Performance appraisals emphasize behavior, effort, rather than results. | 0.649 | |||

| 10. Performance appraisals emphasize future skill development rather than past goal achievement. | 0.698 | |||

| 11. Employees are treated well in terms of salary and various benefits compared to their peers. | 0.729 | |||

| 12. Employees widely hold equity, options, or dividend rights. | 0.626 | |||

| 13. Employees at all levels are as equal as possible in terms of income, status, and culture. | 0.579 | |||

| 14. Employees are involved in decision-making through employee suggestion systems, employee complaint systems, and employee morale surveys. | 0.734 | |||

| 15. Supervisors communicate openly and share all kinds of information with employees. | 0.785 | |||

| 16. Emphasize the pursuit of achieving high goals. | 0.542 | |||

| 17. Emphasize teamwork and collectivism rather than individual struggle. | 0.522 |

| Mold | Factor Structure | CMIN | DF | CMIN/DF | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | Within-Group SRMR | Between-Group SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | WFF, PC, HCWS, PB | 1840.429 | 544 | 3.383 | 0.044 | 0.901 | 0.891 | 0.060 | 0.160 |

| Model 2 | WFF + PC, HCWS, PB | 4275.450 | 551 | 7.759 | 0.075 | 0.716 | 0.691 | 0.128 | 0.188 |

| Model 3 | WFF + PC + HCWS, PB | 4406.323 | 553 | 7.968 | 0.076 | 0.707 | 0.681 | 0.131 | 0.308 |

| Model 4 | WFF + PC + HCWS + PB | 6155.576 | 555 | 11.091 | 0.091 | 0.573 | 0.538 | 0.155 | 0.314 |

| Between-Group Variance t00 | Within-Group Variance σ2 | ICC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological capital | 0.184 | 0.805 | 0.187 |

| Employee proactive behavior | 0.335 | 0.792 | 0.298 |

| Variant | Employee Proactive Behavior | |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Control Variable | ||

| Gender | −0.072 | −0.057 |

| Age | 0.038 | 0.033 |

| Education | −0.056 * | −0.060 * |

| Tenure | 0.013 | −0.001 |

| Marital Status | 0.065 | 0.059 |

| Independent Variable | ||

| Work–family facilitation | 0.176 ** | |

| R2 | 0.007 | 0.066 |

| R2 change | 0.004 | 0.062 ** |

| Variant | Psychological Capital | Employee Proactive Behavior | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Constant | 4.202 ** | 4.948 ** | 1.551 ** |

| Control variable | |||

| Gender | −0.046 | −0.057 | −0.02 |

| Age | 0.04 | 0.033 | 0 |

| Education | −0.051 * | −0.060 * | −0.018 |

| Tenure | −0.001 | −0.001 | 0 |

| Marital status | 0.017 | 0.021 | 0.025 |

| Independent variable | |||

| Work–family facilitation | 0.246 ** | 0.176 ** | 0.017 |

| Psychological capital | 0.808 ** | ||

| R2 | 0.164 | 0.066 | 0.471 |

| R2 change | 0.161 | 0.062 | 0.469 |

| Variant | Employee Proactive Behavior | |

|---|---|---|

| Regression Coefficient | Standard Error | |

| Intercept term | 5.03 *** | 0.36 |

| LEVEL-1 Control Variables | ||

| Age | −0.003 | 0.02 |

| Education | 0.008 | 0.02 |

| Tenure | 0.003 | 0.01 |

| LEVEL-1 Independent Variables | ||

| Psychological capital | 0.61 *** | 0.16 |

| LEVEL-2 Moderating Variables | ||

| High-commitment work system | 0.07 * | 0.07 |

| cross-level interaction | ||

| Psychological capital * High-commitment work system | 0.01 ** | 0.03 |

| R2 | 0.27 ** | |

| R2 change | 0.12 ** | |

| HCWS | Standardized Coefficient | SE | T | p | Lower Interval | Upper Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 0.058 | 0.018 | 3.222 | 0.000 | 0.036 | 0.080 |

| High | 0.098 | 0.019 | 5.020 | 0.000 | 0.060 | 0.136 |

| Difference | 0.040 | 0.010 | 4.000 | 0.000 | 0.025 | 0.055 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, H.; Liu, C.; Zhao, S. The Effect of Work–Family Facilitation on Employee Proactive Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1390. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041390

Zhang H, Liu C, Zhao S. The Effect of Work–Family Facilitation on Employee Proactive Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability. 2025; 17(4):1390. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041390

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Hongyuan, Chang Liu, and Shuming Zhao. 2025. "The Effect of Work–Family Facilitation on Employee Proactive Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model" Sustainability 17, no. 4: 1390. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041390

APA StyleZhang, H., Liu, C., & Zhao, S. (2025). The Effect of Work–Family Facilitation on Employee Proactive Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability, 17(4), 1390. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041390