How Does Forgone Identity Dwelling Foster Perceived Employability: A Self-Regulatory Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

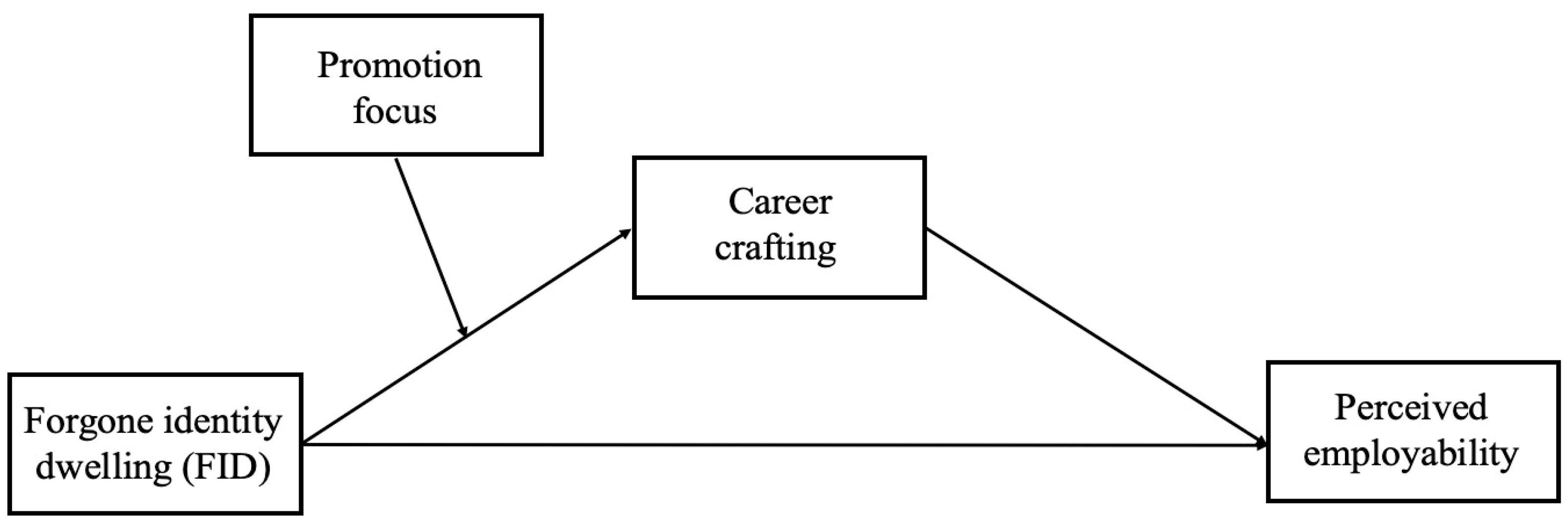

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. FID and Perceived Employability

2.1.1. Self-Regulation Theory

2.1.2. FID as Predictor of Perceived Employability

2.2. The Mediating Effect of Career Crafting in the Relationship Between FID and Perceived Employability

2.3. The Moderating Effect of Promotion Regulatory Focus

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Forgone Identity Dwelling (FID)

3.2.2. Career Crafting

3.2.3. Perceived Employability

3.2.4. Promotion Regulatory Focus

3.2.5. Control Variables

3.3. Analytic Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

4.2. Preliminary Analyses

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fugate, M.; Van Der Heijden, B.; De Vos, A.; Forrier, A.; De Cuyper, N. Is What’s Past Prologue? A Review and Agenda for Contemporary Employability Research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2021, 15, 266–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A.; Koen, J. Contemporary Career Orientations and Career Self-Management: A Review and Integration. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 126, 103505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch, Y.; Sullivan, S.E. The Why, What and How of Career Research: A Review and Recommendations for Future Study. Career Dev. Int. 2022, 27, 135–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, A.; Van Der Heijden, B.I.; Akkermans, J. Sustainable Careers: Towards a Conceptual Model. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 117, 103196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrier, A.; Sels, L. The Concept Employability: A Complex Mosaic. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Dev. Manag. 2003, 3, 102–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkermans, J.; Kubasch, S. #Trending Topics in Careers: A Review and Future Research Agenda. Career Dev. Int. 2017, 22, 586–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decius, J.; Knappstein, M.; Klug, K. Which Way of Learning Benefits Your Career? The Role of Different Forms of Work-Related Learning for Different Types of Perceived Employability. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2024, 33, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, A.; Jacobs, S.; Verbruggen, M. Career Transitions and Employability. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 126, 103475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, M.B.; McCombs, K.; Wiernik, B.M. Movement Capital, RAW Model, or Circumstances? A Meta-Analysis of Perceived Employability Predictors. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 131, 103657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Pan, Z.; Jin, Q.; Feng, Y. Impact of Self-Perceived Employability on Sustainable Career Development in Times of COVID-19: Two Mediating Paths. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A. The Psychology of Sustainability and Sustainable Development for Well-Being in Organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Fabio, A.; Rosen, M.A. Opening the Black Box of Psychological Processes in the Science of Sustainable Development: A New Frontier. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. Res. 2018, 2, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forrier, A.; De Cuyper, N.; Akkermans, J. The Winner Takes It All, the Loser Has to Fall: Provoking the Agency Perspective in Employability Research. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2018, 28, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkermans, J.; Le Blanc, P.; Van der Heijden, B.; De Vos, A. Toward a Contextualized Perspective of Employability Development. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2024, 33, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Harten, J.; de Cuyper, N.; Knies, E.; Forrier, A. Taking the Temperature of Employability Research: A Systematic Review of Interrelationships across and within Conceptual Strands. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2022, 31, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrier, A.; De Cuyper, N.; Delva, J. How Theatre Actors in Flanders Make Sense of and Enact Their Employability in a Context in Motion: A Matter of Fit. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2024, 33, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbatov, S.; Oostrom, J.K.; Khapova, S.N. Work Does Not Speak for Itself: Examining the Incremental Validity of Personal Branding in Predicting Knowledge Workers’ Employability. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2024, 33, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koen, J.; van Bezouw, M.J. Acting Proactively to Manage Job Insecurity: How Worrying about the Future of One’s Job May Obstruct Future-Focused Thinking and Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 727363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, H.; Lee, J. Employee Self-Concepts, Voluntary Learning Behavior, and Perceived Employability. J. Manag. Psychol. 2015, 30, 264–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Presti, A.; De Rosa, A. A Brief Psychometric Report on the Association Between Resource-Based Employability and Perceived Employability. Psychol. Stud. 2024, 69, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praskova, A.; Creed, P.A.; Hood, M. Career Identity and the Complex Mediating Relationships between Career Preparatory Actions and Career Progress Markers. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 87, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obodaru, O. The Self Not Taken: How Alternative Selves Develop and How They Influence Our Professional Lives. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 34–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obodaru, O. Forgone, but Not Forgotten: Toward a Theory of Forgone Professional Identities. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 523–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, R.; Colquitt, J.A.; Long, E.C. Longing for the Road Not Taken: The Affective and Behavioral Consequences of Forgone Identity Dwelling. Acad. Manag. J. 2022, 65, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Li, Z. Workplace Hierarchical Plateau and Employees’ Work Engagement: Mediating Effect of Forgone Identity Dwelling. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2021, 49, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, A.; Akkermans, J.; Van der Heijden, B. From Occupational Choice to Career Crafting. In The Routledge Companion to Career Studies; Gunz, H., Lazarova, M., Mayrhofer, W., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 128–142. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F. On the Self-Regulation of Behavior; Cambridge University Press: Cambrige, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F. Attention and Self-Regulation: A Control-Theory Approach to Human Behavior; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D. Social Cognitive Model of Career Self-Management: Toward a Unifying View of Adaptive Career Behavior across the Life Span. J. Couns. Psychol. 2013, 60, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, R.G.; Diefendorff, J.M.; Schmidt, A.M.; Hall, R.J. Self-Regulation at Work. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2010, 61, 543–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Akkermans, J. Job and Career Crafting to Fulfill Individual Career Pathways. In Career Pathways–School to Retirement and Beyond; Carter, G., Hedge, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 165–190. [Google Scholar]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D. Social Cognitive Career Theory at 25: Empirical Status of the Interest, Choice, and Performance Models. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 115, 103316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. Beyond Pleasure and Pain. Am. Psychol. 1997, 52, 1280–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T.; Spiegel, S. Promotion and Prevention Strategies for Self-Regulation. In Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory, and Applications; Vohs, K.D., Baumeister, R.F., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 171–187. [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell, A.; Arnold, J. Self-perceived Employability: Development and Validation of a Scale. Pers. Rev. 2007, 36, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhercke, D.; De Cuyper, N.; Peeters, E.; De Witte, H. Defining Perceived Employability: A Psychological Approach. Pers. Rev. 2014, 43, 592–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miscenko, D.; Day, D.V. Identity and Identification at Work. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 6, 215–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.M. The Rational Imagination: How People Create Alternatives to Reality; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; Boehm, J.K.; Kasri, F.; Zehm, K. The Cognitive and Hedonic Costs of Dwelling on Achievement-Related Negative Experiences: Implications for Enduring Happiness and Unhappiness. Emotion 2011, 11, 1152–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, E.T. Self-Discrepancy: A Theory Relating Self and Affect. Psychol. Rev. 1987, 94, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markus, H.; Nurius, P. Possible Selves. Am. Psychol. 1986, 41, 954–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Jiang, X.; Khapova, S.N.; Qu, J. Workplace-Related Negative Career Shocks on Perceived Employability: The Role of Networking Behaviors and Perceived Career Opportunities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praskova, A.; Creed, P.A.; Hood, M. Self-Regulatory Processes Mediating between Career Calling and Perceived Employability and Life Satisfaction in Emerging Adults. J. Career Dev. 2015, 42, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ngo, H.; Chui, H. The Impact of Future Work Self on Perceived Employability and Career Distress. Aust. J. Career Dev. 2023, 32, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, E.; van der Heijden, B.I.; Akkermans, J.; Audenaert, M. Unraveling the Complex Relationship between Career Success and Career Crafting: Exploring Nonlinearity and the Moderating Role of Learning Value of the Job. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 130, 103620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, A.; De Clippeleer, I.; Dewilde, T. Proactive Career Behaviours and Career Success during the Early Career. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 82, 761–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Development and Validation of the Job Crafting Scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkermans, J.; Brenninkmeijer, V.; Huibers, M.; Blonk, R.W. Competencies for the Contemporary Career: Development and Preliminary Validation of the Career Competencies Questionnaire. J. Career Dev. 2013, 40, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Hood, M.; Creed, P.A. Negative Career Feedback and Career Outcomes: The Mediating Roles of Self-Regulatory Processes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 106, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucbasaran, D.; Shepherd, D.A.; Lockett, A.; Lyon, S.J. Life After Business Failure: The Process and Consequences of Business Failure for Entrepreneurs. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 163–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, L.M.; Kraimer, M.L. Goal-Setting in the Career Management Process: An Identity Theory Perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A.; Nagy, N.; Baumeler, F.; Johnston, C.S.; Spurk, D. Assessing Key Predictors of Career Success: Development and Validation of the Career Resources Questionnaire. J. Career Assess. 2018, 26, 338–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, A.M.W.; Bai, J.Y.; Luo, J.M.; Fan, D.X. Why Do Negative Career Shocks Foster Perceived Employability and Career Performance: A Career Crafting Explanation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 119, 103724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkermans, J.; Hirschi, A. Career Proactivity: Conceptual and Theoretical Reflections. Appl. Psychol. 2023, 72, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkermans, J.; Tims, M. Crafting Your Career: How Career Competencies Relate to Career Success via Job Crafting. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 66, 168–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signore, F.; Ciavolino, E.; Cortese, C.G.; De Carlo, E.; Ingusci, E. The Active Role of Job Crafting in Promoting Well-Being and Employability: An Empirical Investigation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysova, E.I.; Jansen, P.G.; Khapova, S.N.; Plomp, J.; Tims, M. Examining Calling as a Double-Edged Sword for Employability. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 104, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Qu, J.; Lei, M.; Zhou, W. How Do Proactive Career Behaviors Translate into Subjective Career Success and Perceived Employability? The Role of Thriving at Work and Humble Leadership. J. Manag. Organ. 2023, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockner, J.; Higgins, E.T. Regulatory Focus Theory: Implications for the Study of Emotions at Work. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2001, 86, 35–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lau, D.C.; Kim, Y. Accentuating the Positive: How and When Occupational Identity Threat Leads to Job Crafting and Positive Outcomes. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2024, 97, 131–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. How Regulatory Fit Creates Value. In Social Psychology and Economics; De Cremer, D., Zeelenberg, M., Murnighan, J.K., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, X.; Chen, C.; Yam, K.C.; Huang, M.; Ju, D. The Double-Edged Sword of Leader Humility: Investigating When and Why Leader Humility Promotes versus Inhibits Subordinate Deviance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-Translation for Cross-Cultural Research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, P.; Jordan, C.H.; Kunda, Z. Motivation by Positive or Negative Role Models: Regulatory Focus Determines Who Will Best Inspire Us. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 854–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.R.; Namasivayam, K. The Relationship of Chronic Regulatory Focus to Work–Family Conflict and Job Satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Lambert, L.S. Methods for Integrating Moderation and Mediation: A General Analytical Framework Using Moderated Path Analysis. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’brien, R.M. A Caution Regarding Rules of Thumb for Variance Inflation Factors. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetty van Emmerik, I.; Schreurs, B.; De Cuyper, N.; Jawahar, I.; Peeters, M.C. The Route to Employability: Examining Resources and the Mediating Role of Motivation. Career Dev. Int. 2012, 17, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 0.63 | 0.48 | - | |||||||

| 2. Age | 26.38 | 2.88 | −0.11 * | − | ||||||

| 3. Tenure | 2.53 | 1.88 | −0.09 | 0.44 ** | − | |||||

| 4. Education | 3.15 | 0.57 | 0.02 | 0.14 ** | −0.10 * | − | ||||

| 5. FID | 2.93 | 0.86 | −0.01 | −0.18 ** | 0.02 | −0.20 ** | (0.88) | |||

| 6. Career crafting | 3.38 | 0.53 | −0.09 | −0.10 * | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.38 ** | (0.80) | ||

| 7. PE | 4.38 | 0.56 | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.07 | −0.06 | 0.30 ** | 0.53 ** | (0.84) | |

| 8. Promotion focus | 5.43 | 0.82 | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.23 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.45 ** | (0.87) |

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: Four-factor Model a | 756.90 *** | 424 | 1.79 | 0.04 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.05 |

| B: Three-factor Model b | 1309.74 *** | 429 | 3.05 | 0.07 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.06 |

| C: Two-factor Model c | 1854.47 *** | 433 | 4.28 | 0.09 | 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.08 |

| D: One-factor Model d | 2450.35 *** | 434 | 5.65 | 0.10 | 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.10 |

| Constructs | Items | Loadings | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forgone identity dwelling | FID_1 | 0.80 | 0.88 | 0.72 |

| FID_2 | 0.87 | |||

| FID_3 | 0.87 | |||

| Career crafting | CC_1 | 0.68 | 0.90 | 0.52 |

| CC_2 | 0.74 | |||

| CC_3 | 0.76 | |||

| CC_4 | 0.73 | |||

| CC_5 | 0.68 | |||

| CC_6 | 0.69 | |||

| CC_7 | 0.71 | |||

| CC_8 | 0.78 | |||

| Promotion focus | PF_1 | 0.80 | 0.91 | 0.54 |

| PF_2 | 0.81 | |||

| PF_3 | 0.80 | |||

| PF_4 | 0.76 | |||

| PF_5 | 0.75 | |||

| PF_6 | 0.71 | |||

| PF_7 | 0.51 | |||

| PF_8 | 0.69 | |||

| PF_9 | 0.73 | |||

| Perceived employability | PE_1 | 0.69 | 0.92 | 0.51 |

| PE_2 | 0.70 | |||

| PE_3 | 0.68 | |||

| PE_4 | 0.70 | |||

| PE_5 | 0.68 | |||

| PE_6 | 0.71 | |||

| PE_7 | 0.71 | |||

| PE_8 | 0.72 | |||

| PE_9 | 0.74 | |||

| PE_10 | 0.74 | |||

| PE_11 | 0.76 |

| Career Crafting | Perceived Employability | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

| Constant | 2.70 *** | 0.29 | 2.30 *** | 0.30 |

| Control variables | ||||

| Gender | −0.11 * | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Tenure | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Education | 0.12 ** | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.04 |

| Independent variable | ||||

| Forgone identity dwelling | 0.24 *** | 0.03 | 0.07 * | 0.03 |

| Mediator | ||||

| Career crafting | 0.52 *** | 0.05 | ||

| R2 | 0.17 *** | 0.30 *** | ||

| Career Crafting | Perceived Employability | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

| Constant | 3.41 *** | 0.24 | 2.83 *** | 0.28 |

| Control variables | ||||

| Gender | −0.10 * | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Tenure | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Education | 0.11 * | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.04 |

| Independent variables | ||||

| Forgone identity dwelling | 0.20 *** | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| Promotion focus | 0.21 *** | 0.03 | 0.19 *** | 0.03 |

| Forgone identity dwelling × Promotion focus | 0.07 * | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.03 |

| Mediator | ||||

| Career crafting | 0.42 *** | 0.05 | ||

| R2 | 0.27 *** | 0.37 *** | ||

| Mediation Effect | Indirect Effect | |

|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 95% CI | |

| Forgone identity dwelling to perceived employability via career crafting | 0.13 | [0.09, 0.17] |

| Moderated Mediation Effect | Conditional Indirect Effect | |

| Estimate | 95% CI | |

| Promotion focus | ||

| High (+1 SD) | 0.11 | [0.07, 0.16] |

| Low (−1 SD) | 0.06 | [0.03, 0.10] |

| Difference (high–low) | 0.05 | [0.01, 0.09] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, W.; Feng, Y.; Jiang, X. How Does Forgone Identity Dwelling Foster Perceived Employability: A Self-Regulatory Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9614. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16229614

Zhou W, Feng Y, Jiang X. How Does Forgone Identity Dwelling Foster Perceived Employability: A Self-Regulatory Perspective. Sustainability. 2024; 16(22):9614. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16229614

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Wenxia, Yue Feng, and Xinling Jiang. 2024. "How Does Forgone Identity Dwelling Foster Perceived Employability: A Self-Regulatory Perspective" Sustainability 16, no. 22: 9614. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16229614

APA StyleZhou, W., Feng, Y., & Jiang, X. (2024). How Does Forgone Identity Dwelling Foster Perceived Employability: A Self-Regulatory Perspective. Sustainability, 16(22), 9614. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16229614