Environmental Awareness and Moral Commitment in Water Usage in Gastronomy SMEs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Contextual Framework

2.1. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

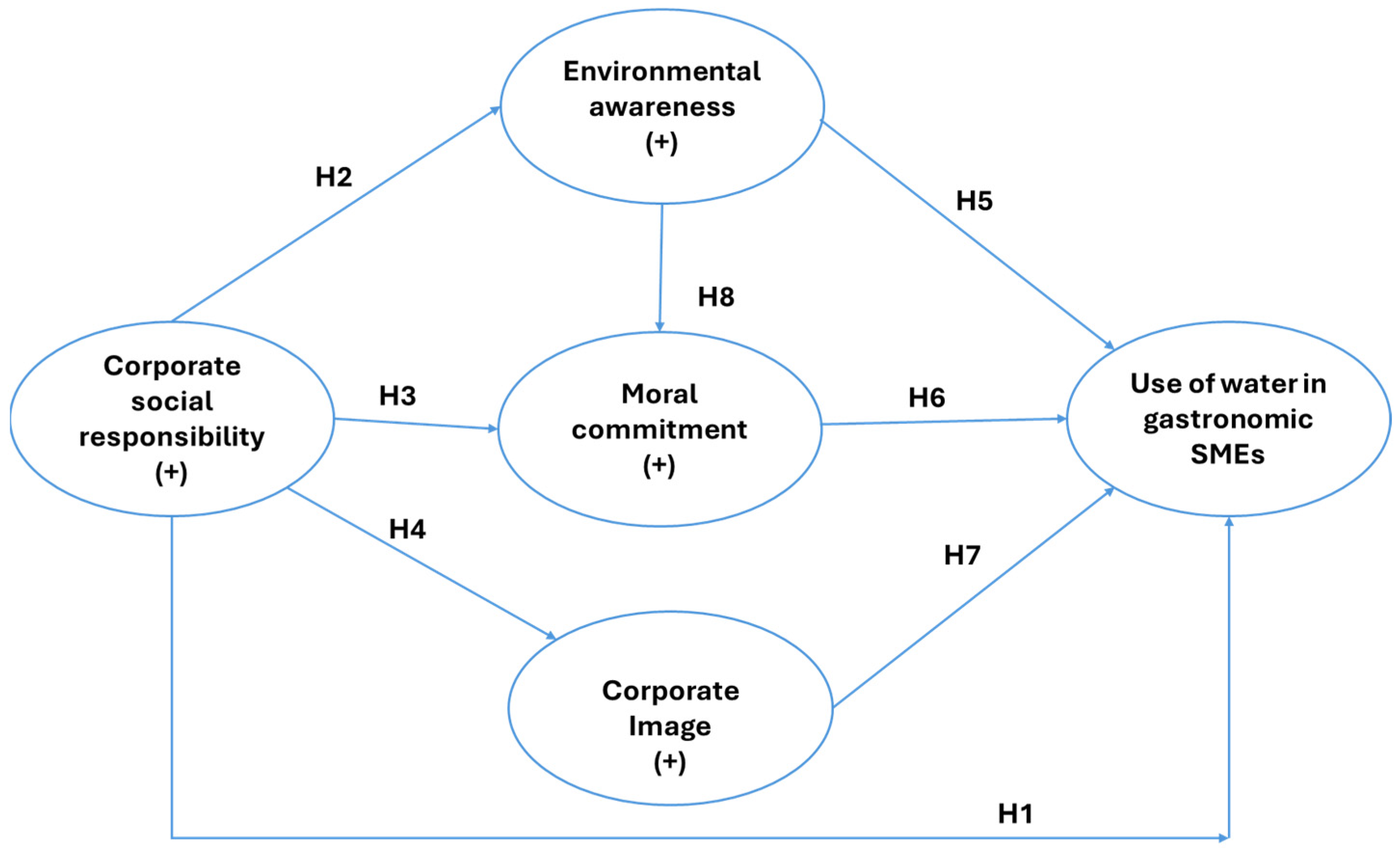

2.2. CSR and the Intention for Sustainable Water Use

2.3. CSR and Environmental Awareness

2.4. CSR and Moral Commitment

2.5. CSR and Corporate Image

2.6. Environmental Awareness and Intention for Sustainable Water Use

2.7. Moral Commitment and Intention for Sustainable Water Use

2.8. Corporate Image and Intention for Sustainable Water Use

2.9. Environmental Awareness and Moral Commitment

3. Materials and Methods

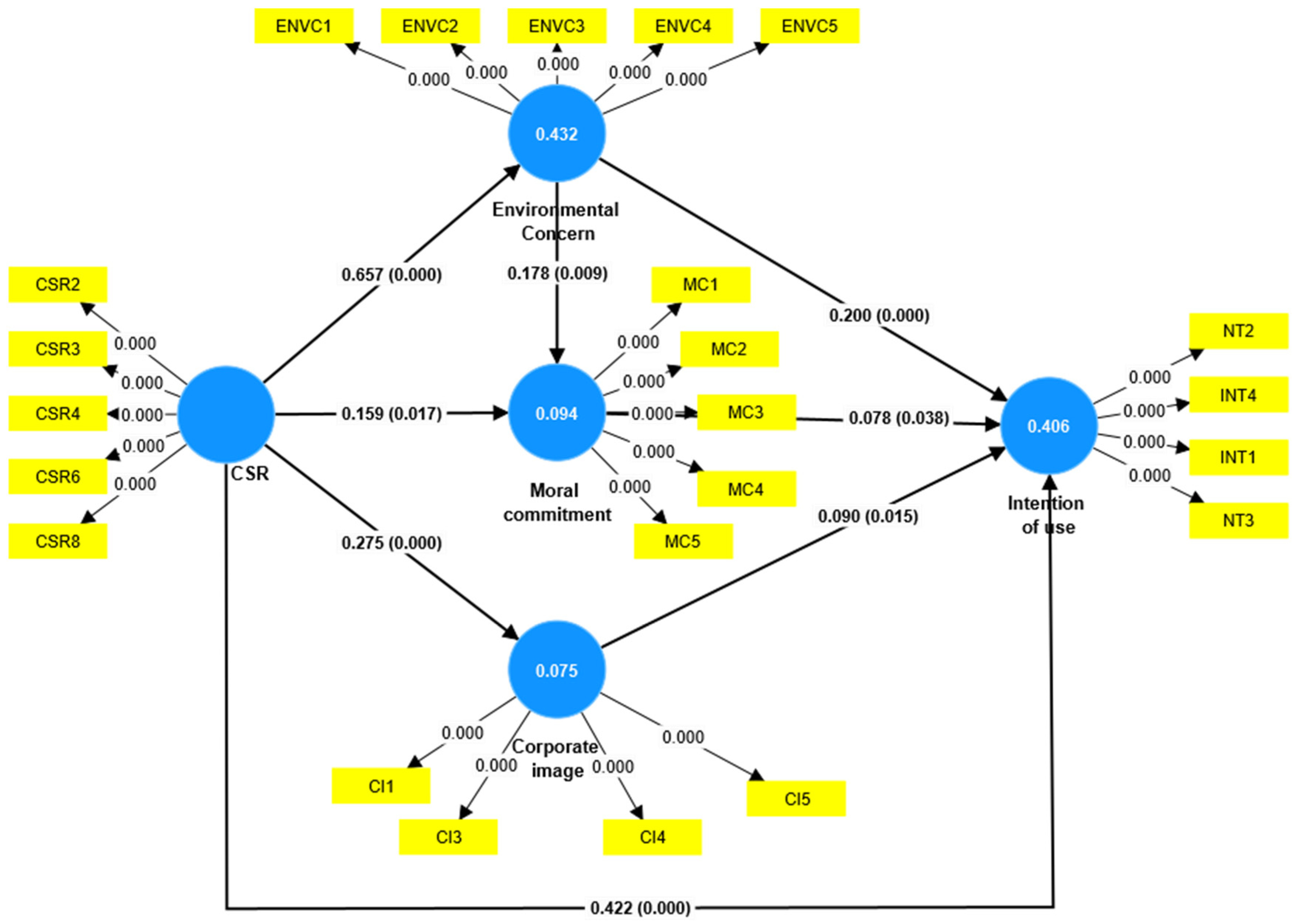

4. Results

4.1. Data Analysis

4.2. Demographic Data

4.3. Model Validation

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Limitations of the Study

6.2. Implications of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Questions | References |

|---|---|---|

| CSR1 | Owners/managers are informed about relevant environmental laws | Kim et al. (2017) [26] |

| CSR2 | The restaurant makes efforts to fairly treat customers | Kim et al. (2017) [26] |

| CSR3 | Employees of our organization follow professional standards | Kim et al. (2017) [26] |

| CSR4 | The restaurant properly implements health and safety rules and regulations | Chen et al. (2021) [26] |

| CSR5 | The restaurant tries to contribute toward bettering the local community | Kim et al. (2017) [26] |

| CSR6 | The restaurant participates in a variety of volunteer activities by starting the company’s volunteer group. | Chen et al. (2021) [25] |

| CSR7 | The restaurant generates employment through its operations | Chen et al. (2021) [25] |

| CSR8 | We continually improve the quality of our products/service | Kim et al. (2017) [26] |

| IC1 | In my opinion, the restaurant has a good image in the minds of consumers | Chen et al. (2021) [27] |

| IC2 | The restaurant has a poweful image | Chen et al. (2021) [27] |

| IC3 | I have good impressions of the restaurant | Chen et al. (2021) [25] |

| IC4 | The appearance of the restaurant is appealing | Chen et al. (2021) [25] |

| IC5 | We work in a great restaurant | Chen et al. (2021) [25] |

| ENVC1 | I am very concerned about the environment | Dangelico, Alvino and Fraccascia (2022) [45] Rausch and Kopplin (2021) [44] |

| ENVC2 | I would be willing to reduce or change my consumption to help protect the environment | |

| ENVC3 | Protecting the natural environment increases my quality of life | |

| ENVC4 | I am concerned about the long-term consequences of unsustainable behavior | |

| ENVC5 | I am concerned that humanity will cause a lasting damage towards the environment | |

| MC1 | The environmental concern of my restaurant means a lot to me | Keles, Yayla, Tarinc, and Keles (2023) [48] Yayla et al. (2020) [49] |

| MC2 | I feel a sense of duty to support the environmental efforts of my restaurant. | |

| MC3 | I really feel as if my hotel’s environmental problems are my own | |

| MC4 | I think that I will deal with environmental activities more in the future. | |

| MC5 | I am quite committed to the natural environment of the business I work for. | |

| INT1 | I will try to save water in my activities | Mitev et al. (2024) [50] Fatoki (2022) [51] |

| INT2 | The next time that washing fruit and vegetables I will use a bowl of cold water rather than continuously running the tap | |

| INT3 | I intend to save water in the restaurant | |

| INT4 | I am willing to save water in the restaurant |

References

- Munasinghe, M. Millennium Consumption Goals (MCGs) for Rio+20 and beyond: A practical step towards global sustainability. Nat. Resour. Forum 2012, 36, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-L.; Chen, H.; Wang, H.-L.; Chen, X.; Yang, H.-C.; Darling, S.B. Solar-driven evaporators for water treatment: Challenges and opportunities. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2021, 7, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Novo, F. Moral drought: The ethics of water use. Water Policy 2012, 14, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DGA. Boletines Hidrológicos. 2022. Available online: http://bcn.cl/326v1 (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Garreaud, R.D.; Boisier, J.P.; Rondanelli, R.; Montecinos, A.; Sepúlveda, H.H.; Veloso-Aguila, D. The Central Chile Mega Drought (2010–2018): A climate dynamics perspective. Int. J. Climatol. 2020, 40, 421–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferasso, M.; Bares, L.; Ogachi, D.; Blanco, M. Economic and Sustainability Inequalities and Water Consumption of European Union Countries. Water 2021, 13, 2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, R.; Khan, K.U.; Zain, F.; Atlas, F. Buy green only: Interplay between green marketing, corporate social responsibility and green purchase intention; the mediating role of green brand image. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2023, 6, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchini, M.; Evangelista Mauad, A.C. La gobernanza ambiental global tras el Acuerdo de París y los ODS: Crisis ambiental, pandemia y conflicto geopolítico sistémico. Desafíos 2022, 34, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera Castro, A.; Puerto Becerra, D.P. Crecimiento empresarial basado en la Responsabilidad Social. Pensam. Gestión 2012, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Viet, B.; Thanh Tran, C. Sustaining organizational customers’ consumption through corporate social responsibility and green advertising receptivity: The mediating role of green trust. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2287775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T.; Huan, N.Q.; Hong TT, T.; Tran, D.K. The contribution of corporate social responsibility on SMEs performance in emerging country. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 322, 129103. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibiiity: Toward the Morai Management of Organizational Stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfajfar, G.; Shoham, A.; Małecka, A.; Zalaznik, M. Value of corporate social responsibility for multiple stakeholders and social impact—Relationship marketing perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 143, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.L.; Rhou, Y.; Uysal, M.; Kwon, N. An examination of the links between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and its internal consequences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 61, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.T.; Der Lin, M.; Khan, A. The impact of CSR on green purchase intention: Empirical evidence from the green building Industries in Taiwan. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1055505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, H.; Chua, B.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Untaru, E. Effect of environmental corporate social responsibility on green attitude and norm activation process for sustainable consumption: Airline versus restaurant. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1851–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 10, 221–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkurinen, P. Strategic corporate responsibility: A theory review and synthesis. J. Glob. Responsib. 2018, 9, 388–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah SH, H.; Lei, S.; Hussain, S.T.; Mariam, S. How consumer perceived ethicality influence repurchase intentions and word-of-mouth? A mediated moderation model. Asian J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.; Kim, H. Are Ethical Consumers Happy? Effects of Ethical Consumers’ Motivations Based on Empathy Versus Self-orientation on Their Happiness. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 579–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, J.D.; Tsarenko, Y.; Ferraro, C.; Sands, S. Environmental concern and environmental purchase intentions: The mediating role of learning strategy. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1974–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Pérez, J.; Garza-Muñiz, V.S.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; García-Salirrosas, E.E.; Esponda-Pérez, J.A.; Álvarez-Becerra, R. The Future of Tamaulipas MSMEs after COVID-19: Intention to Adopt Inbound Marketing Tools. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Orgnizational Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golob, U.; Podnar, K.; Koklič, M.K.; Zabkar, V. The importance of corporate social responsibility for responsible consumption: Exploring moral motivations of consumers. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Khan, A.; Hongsuchon, T.; Ruangkanjanases, A.; Chen, Y.T.; Sivarak, O.; Chen, S.C. The role of corporate social responsibility and corporate image in times of crisis: The mediating role of customer trust. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 8275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.H. A Study of the Integrated Model with Norm Activation Model and Theory of Planned Behavior: Applying the Green Hotel’s Corporate Social Responsibilities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.; Jong, D.; Hsu, C.S.; Lin, C.H. Understanding Extended Theory of Planned Behavior to Access Backpackers’ Intention in Self-Service Travel Websites. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2021, 47, 106–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, C. Corporate social responsibilities, consumer trust and corporate reputation: South Korean consumers’ perspectives. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Díaz, R.R.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Salazar-Sepúlveda, G.; Castillo, D. Contributions of Subjective Well-Being and Good Living to the Contemporary Development of the Notion of Sustainable Human Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patak, M.; Branska, L.; Pecinova, Z. Consumer Intention to Purchase Green Consumer Chemicals. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, B.A.; Elhag, G.M.; Bhatti, M.K.; Abdelwahed NA, A.; Shah, N. Developing environmental performance through sustainable practices, environmental CSR and behavioural intentions: An online approach during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc. Responsib. J. 2024, 20, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, S.; Long, Y.; Rana, S. The role of corporate social responsibility and government incentives in installing industrial wastewater treatment plants: SEM-ANN deep learning approach. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikhide, J.E.; Tarik Timur, A.; Ogunmokun, O.A. The strategic intersection of HR and CSR: CSR motive and millennial joining intention. J. Manag. Organ. 2024, 30, 623–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela-Fernández, L.; Guerra-Velásquez, M.; Escobar-Farfán, M.; García-Salirrosas, E.E. Influence of COVID-19 on environmental awareness, sustainable consumption, and social responsibility in Latin American countries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, S.; Afsar, B.; Al-Ghazali, B.M.; Maqsoom, A. Retracted: How employee’s perceived corporate social responsibility affects employee’s pro-environmental behaviour? The influence of organizational identification, corporate entrepreneurship, and environmental consciousness. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah SH, A.; Al-Ghazali, B.M.; Bhatti, S.; Aman, N.; Fahlevi, M.; Aljuaid, M.; Hasan, F. The impact of Perceived CSR on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors: The mediating effects of environmental consciousness and environmental commitment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad-Segura, E.; Cortés-García, F.J.; Belmonte-Ureña, L.J. The Sustainable Approach to Corporate Social Responsibility: A Global Analysis and Future Trends. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, H.; Shi, J.; Tang, D.; Wu, G.; Lan, J. Understanding intention and behavior toward sustainable usage of bike sharing by extending the theory of planned behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 152, 104513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.K.; Tang, Z.; Popp, J.; Acevedo-Duque, Á. Complexity in the use of 5G technology in China: An exploration using fsQCA approach. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2023; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Wu, Y.; Mehmood, K.; Jabeen, F.; Iftikhar, Y.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Kwan, H.K. Impact of Spectators’ Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility on Regional Attachment in Sports: Three-Wave Indirect Effects of Spectators’ Pride and Team Identification. Sustainability 2021, 13, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Xuhui, W.; Nasiri, A.; Ayyub, S. Determinant factors influencing organic food purchase intention and the moderating role of awareness: A comparative analysis. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 63, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imani, B.; Allahyari, M.S.; Bondori, A.; Surujlal, J.; Sawicka, B. Determinants of organic food purchases intention: The application of an extended theory of planned behaviour. Future Food J. Food Agric. Soc. 2021, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, D.; Kant, R. Green purchasing behaviour: A conceptual framework and empirical investigation of Indian consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausch, T.M.; Kopplin, C.S. Bridge the gap: Consumers’ purchase intention and behavior regarding sustainable clothing. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Alvino, L.; Fraccascia, L. Investigating the antecedents of consumer behavioral intention for sustainable fashion products: Evidence from a large survey of Italian consumers. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 185, 122010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusyani, E.; Lavuri, R.; Gunardi, A. Purchasing eco-sustainable products: Interrelationship between environmental knowledge, environmental concern, green attitude, and perceived behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruangkanjanases, A.; You, J.J.; Chien, S.W.; Ma, Y.; Chen, S.C.; Chao, L.C. Elucidating the Effect of Antecedents on Consumers’ Green Purchase Intention: An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keles, H.; Yayla, O.; Tarinc, A.; Keles, A. The effect of environmental management practices and knowledge in strengthening responsible behavior: The moderator role of environmental commitment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yayla, Ö.; Kendir, H.; Arsalan, E. Moderator role of gender in the effect of environmental commitment on environmental responsibility behaviour in hotel employees. Bus. Manag. Stud. Int. J. 2020, 8, 3971–3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitev, K.; Rennison, F.; Haggar, P.; Hafner, R.; Lowe, A.; Whitmarsh, L. Encouraging water-saving behavior during a “Moment of Change”: The efficacy of implementation intentions on water conservation during the transition to university. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1465696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatoki, O. Determinants of employee electricity saving behavior in small firms: The role of benefits and leadership. Energies 2022, 15, 3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.Z.; Ertz, M. Water consumption rationalization using demarketing strategies in the Gaza Strip, Palestine. Water Resour. Econ. 2023, 43, 100227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Ullah, S.; Ahmad, M.S.; Cheok, M.Y.; Alenezi, H. Assessing the impact of green consumption behavior and green purchase intention among millennials toward sustainable environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 23335–23347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Searcy, C. Zeitgeist or chameleon? A quantitative analysis of CSR definitions. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1423–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Pérez, J.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Llanos-Herrera, G.R.; García-Salirrosas, E.E.; Ovalles-Toledo, L.V.; Sandoval Barraza, L.A.; Álvarez-Becerra, R. The Mexican Ecological Conscience: A Predictive Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Müller, S.; Kalia, P.; Mehmood, K. Predictive Sustainability Model Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior Incorporating Ecological Conscience and Moral Obligation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.T.; Liu, N.C.; Lin, J.W. Firms’ adoption of CSR initiatives and employees’ organizational commitment: Organizational CSR climate and employees’ CSR-induced attributions as mediators. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 140, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbdelAzim, T.S.; Kassem, A.; Alajloni, A.; Alomran, A.; Ragab, A.; Shaker, E. Effect of internal corporate social responsibility activities on tourism and hospitality employees ‘normative commitment during COVID-19. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2022, 18, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukatos, D.; Androulidakis, N.; Arvanitis, K.G.; Peppas, K.P.; Chondrogiannis, E. Using Open Tools to Transform Retired Equipment into Powerful Engineering Education Instruments: A Smart Agri-IoT Control Example. Electronics 2022, 11, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Soucie, K.; Alisat, S.; Curtin, D.; Pratt, M. Are environmental issues moral issues? Moral identity in relation to protecting the natural world. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 52, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchanapibul, M.; Lacka, E.; Wang, X.; Chan, H.K. An empirical investigation of green purchase behaviour among the young generation. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Qu, X. Impact of environmental CSR on firm’s environmental performance, mediating role of corporate image and pro-environmental behavior. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 32255–32269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saran, S.M.; Shokouhyar, S. Crossing the chasm between green corporate image and green corporate identity: A text mining, social media-based case study on automakers. J. Strateg. Mark. 2023, 31, 116–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgias, S.L. “Subsidizing the State:” The political ecology and legal geography of social movements in Chilean water governance. Geoforum 2018, 95, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, I.; Martin, A.; Wicker, A.; Benoit, L. Understanding youths’ concerns about climate change: A binational qualitative study of ecological burden and resilience. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2022, 16, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, J.M.; Sarabia-Sanchez, F.J.; Bianchi, E.C. CSR practices, identification and corporate reputation. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. De Adm. 2020, 33, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestrini, P.; Gamble, P. Country-of-origin effects on Chinese wine consumers. Br. Food J. 2006, 108, 396–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, B.; Lynch, D.; Lowe, J. Reducing household water consumption: A social marketing approach. J. Mark. Manag. 2015, 31, 378–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Apraiz, J.C.; Carrión, G.A.C.; Roldán, J.L. Manual de Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) (Segunda Edición). In Manual de Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; OmniaScience: Barcelona, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Pick, M.; Liengaard, B.D.; Radomir, L.; Ringle, C.M. Progress in partial least squares structural equation modeling use in marketing research in the last decade. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 20, 277–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.R.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariante Data Analysis (Setima); Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N. Common Method Bias in PLS-SEM. Int. J. E-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach to Structural Modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Conklin, M.; Bordi, P.; Cranage, D. Restaurants’ healthy eating initiatives for children increase parents’ perceptions of CSR, empowerment, and visit intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 59, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Alvi, A.; Ittefaq, M. The Use of Social Media on Political Participation Among University Students: An Analysis of Survey Results From Rural Pakistan; SAGE Open: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019; Volume 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz Martínez, C. La Responsabilidad Social Corporativa (RSC), el Pacto Mundial de las Naciones Unidas y Análisis Práctico Sobre la Contribución de Diferentes Organizaciones a los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible (ODS) = Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). The United Nations Global Compact and Practical Analysis on the Contribution of Different Organizations to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGS). 2021. Available online: https://buleria.unileon.es/handle/10612/14464 (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Park, H.-H.; Shin, G.-C.; Lew, Y.K. An Application of the Norm Activation Model to Fair Trade Product Purchase Decision-Making Process: The Moderating Impact of Cultural Cluster. Int. Bus. J. 2017, 28, 45–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Man | 149 | 42.20 |

| Woman | 204 | 57.79 |

| Age | ||

| 18–22 | 47 | 12.0 |

| 23–27 | 70 | 17.9 |

| 28–32 | 41 | 10.5 |

| 33–37 | 47 | 12.0 |

| 38–42 | 36 | 9.2 |

| 43–47 | 42 | 10.7 |

| 48–52 | 37 | 9.4 |

| Older than 52 | 33 | 8.4 |

| Time working | ||

| Less than 6 months | 36 | 9.2 |

| 6 months to 1 year | 72 | 18.4 |

| 1 to 2 years | 119 | 30.4 |

| More than 2 years | 126 | 32.2 |

| Job position | ||

| Kitchen | 111 | 28.3 |

| Toilet | 7 | 1.8 |

| Cafeteria | 2 | 0.5 |

| Barista | 5 | 1.3 |

| Cashier | 62 | 15.8 |

| Waiter | 139 | 35.5 |

| Dishwasher | 3 | 0.8 |

| Manager or supervisor | 24 | 6.1 |

| Items | Charges >0.70 | AVE >0.50 | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Rho_A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention of sustainable water use | |||||

| INT1 | 0.821 | 0.741 | 0.883 | 0.919 | 0.886 |

| INT2 | 0.844 | ||||

| INT3 | 0.887 | ||||

| INT4 | 0.889 | ||||

| Moral commitment | |||||

| MC1 | 0.769 | 0.596 | 0.830 | 0.881 | 0.837 |

| MC2 | 0.700 | ||||

| MC3 | 0.773 | ||||

| MC4 | 0.792 | ||||

| MC5 | 0.823 | ||||

| Corporate image | |||||

| CI1 | 0.710 | 0.597 | 0.778 | 0.855 | 0.783 |

| CI3 | 0.786 | ||||

| CI4 | 0.740 | ||||

| CI5 | 0.848 | ||||

| Corporate social responsibility | |||||

| CSR2 | 0.776 | 0.631 | 0.853 | 0.895 | 0.859 |

| CSR3 | 0.856 | ||||

| CSR4 | 0.826 | ||||

| CSR6 | 0.784 | ||||

| CSR8 | 0.723 | ||||

| Environmental awareness | |||||

| ENVC1 | 0.773 | 0.598 | 0.831 | 0.881 | 0.833 |

| ENVC2 | 0.745 | ||||

| ENVC3 | 0.731 | ||||

| ENVC4 | 0.788 | ||||

| ENVC5 | 0.825 | ||||

| INT | MC | ENVC | CI | CSR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention of sustainable water use | |||||

| Moral commitment | 0.319 | ||||

| Environmental awareness | 0.612 | 0.337 | |||

| Corporate image | 0.339 | 0.355 | 0.370 | ||

| CSR | 0.685 | 0.319 | 0.775 | 0.323 |

| Hypothesis | VIF | Path | p-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR → INT | 1.798 | 0.422 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| CSR → ENVC | 1.000 | 0.657 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| CSR → MC | 1.760 | 0.159 | 0.017 | Accepted |

| CSR → CI | 1.000 | 0.275 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| ENVC → INT | 1.834 | 0.200 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| MC → INT | 1.159 | 0.078 | 0.038 | Accepted |

| CI → INT | 1.171 | 0.090 | 0.015 | Accepted |

| ENVC → MC | 1.760 | 0.178 | 0.009 | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Müller-Pérez, J.; Alvarez-Becerra, R.; Cachicatari-Vargas, E.; Fernández-Mantilla, M.M.; Merino Flores, I.; Yomara Verges, I. Environmental Awareness and Moral Commitment in Water Usage in Gastronomy SMEs. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041379

Acevedo-Duque Á, Müller-Pérez J, Alvarez-Becerra R, Cachicatari-Vargas E, Fernández-Mantilla MM, Merino Flores I, Yomara Verges I. Environmental Awareness and Moral Commitment in Water Usage in Gastronomy SMEs. Sustainability. 2025; 17(4):1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041379

Chicago/Turabian StyleAcevedo-Duque, Ángel, Jessica Müller-Pérez, Rina Alvarez-Becerra, Elena Cachicatari-Vargas, Mirtha Mercedes Fernández-Mantilla, Irene Merino Flores, and Irma Yomara Verges. 2025. "Environmental Awareness and Moral Commitment in Water Usage in Gastronomy SMEs" Sustainability 17, no. 4: 1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041379

APA StyleAcevedo-Duque, Á., Müller-Pérez, J., Alvarez-Becerra, R., Cachicatari-Vargas, E., Fernández-Mantilla, M. M., Merino Flores, I., & Yomara Verges, I. (2025). Environmental Awareness and Moral Commitment in Water Usage in Gastronomy SMEs. Sustainability, 17(4), 1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041379