Distances from Efficiency: A Territorial Assessment of the Performance of the Circular Economy in Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

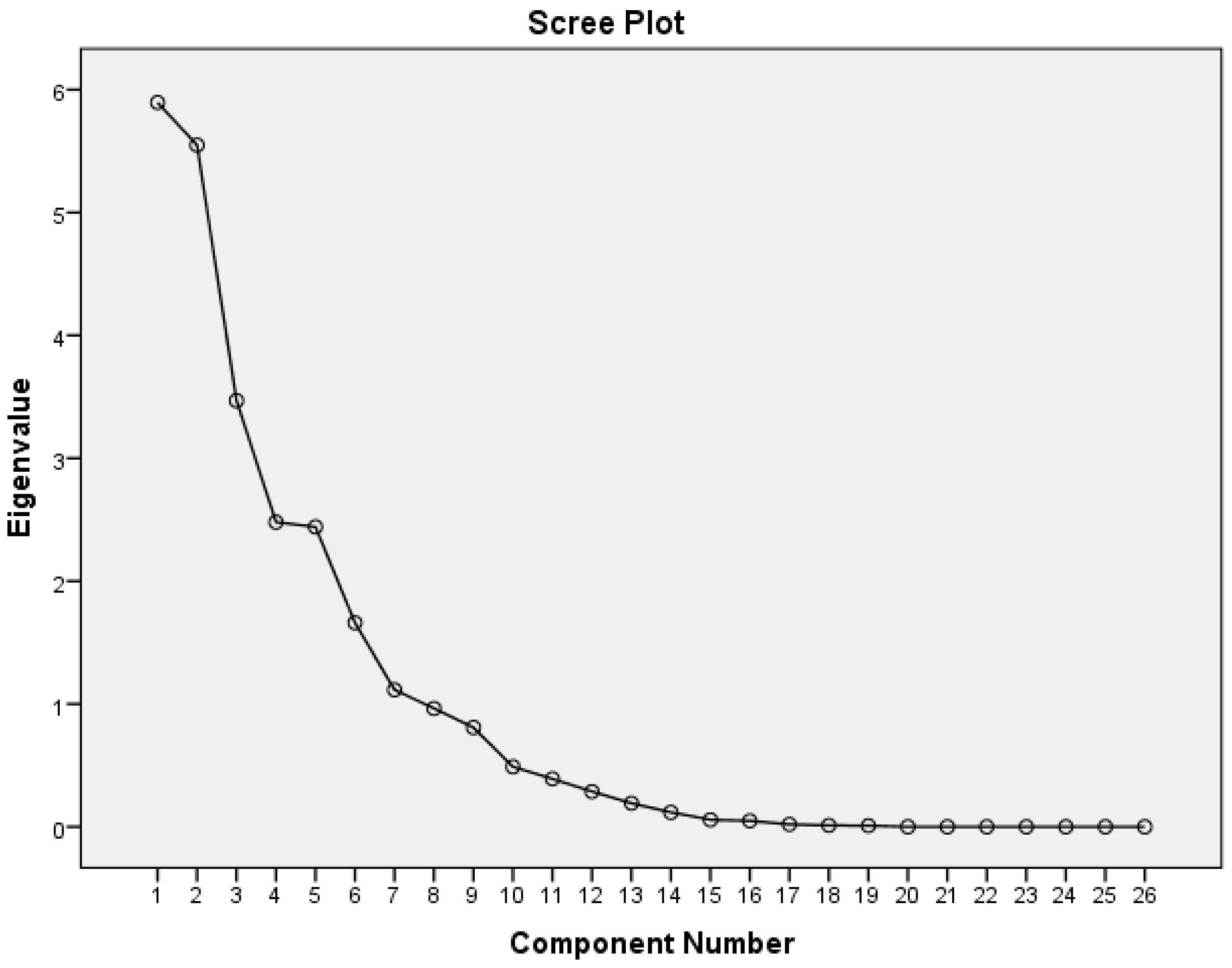

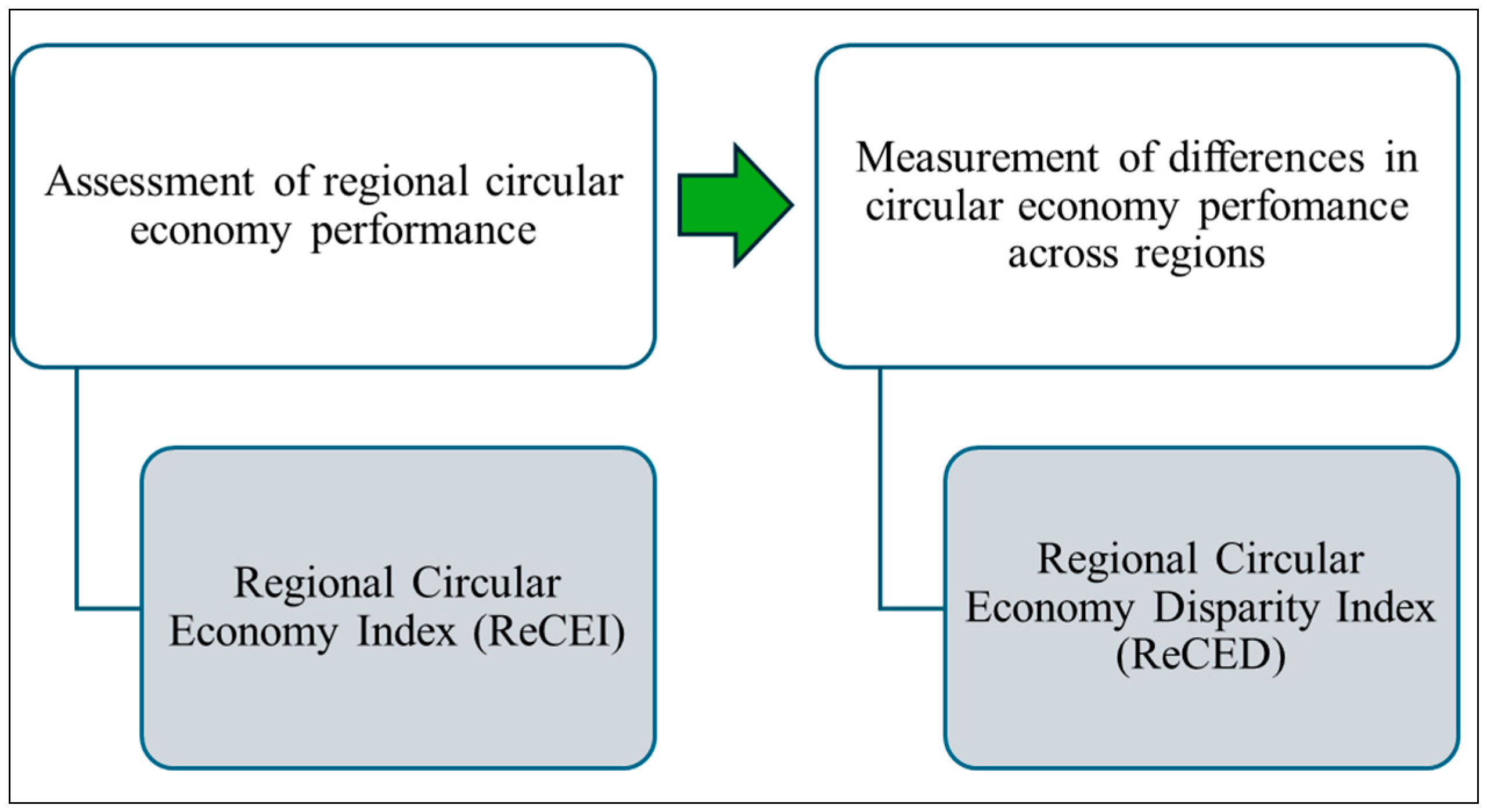

3.1. Construction of Regional Circular Economy Index (ReCEI)

3.2. Measuring Regional Circular Economy Disparity (ReCED)

- Scenario 1—Efficient Performance Threshold. It defines an “efficient value”—z1 as the mean value of ReCEI scores (and of each pillar scores) within the interquartile range between the first and third quartile (Q1–Q3). This threshold captures a realistic benchmark for acceptable circular economy performance while mitigating distortions caused by extreme outliers. This approach aligns with methodologies employed in socioeconomic studies on synthetic index construction, which preferentially utilize robust statistics—such as the interquartile range (IQR) to mitigate the distorting effects of outliers [48,49]. In line with established practices in composite indicators design, robust central tendency benchmarks are widely adopted to ensure stability under distributional irregularities. The OECD methodological framework [41] highlights the importance of IQR-based thresholds to avoid distortions linked to high-leverage observations, and similar principles are applied in multidimensional poverty and vulnerability measures [50,51]. These contributions provide a theoretical framework for interpreting Scenario 1 as a justified threshold rather than an ad hoc statistical choice.

- Scenario 2—Ideal Performance Threshold. It defines an “ideal value”—z2 as the maximum ReCEI value (and the maximum value of each pillar scores) observed within the fourth quartile (Q4). This threshold represents the ideal performance level and highlights the largest disparity in regional performance. The use of an upper-bound or frontier-type benchmark is consistent with the literature on performance gaps, polarization, and frontier evaluation. Studies on relative deprivation and polarization [52,53] employ extreme but empirically observed values to characterize the full span of disparity. This ensures that Scenario 2 captures the upper boundary of feasible performance without relying on hypothetical extreme.

3.3. Data

4. Results and Discussion

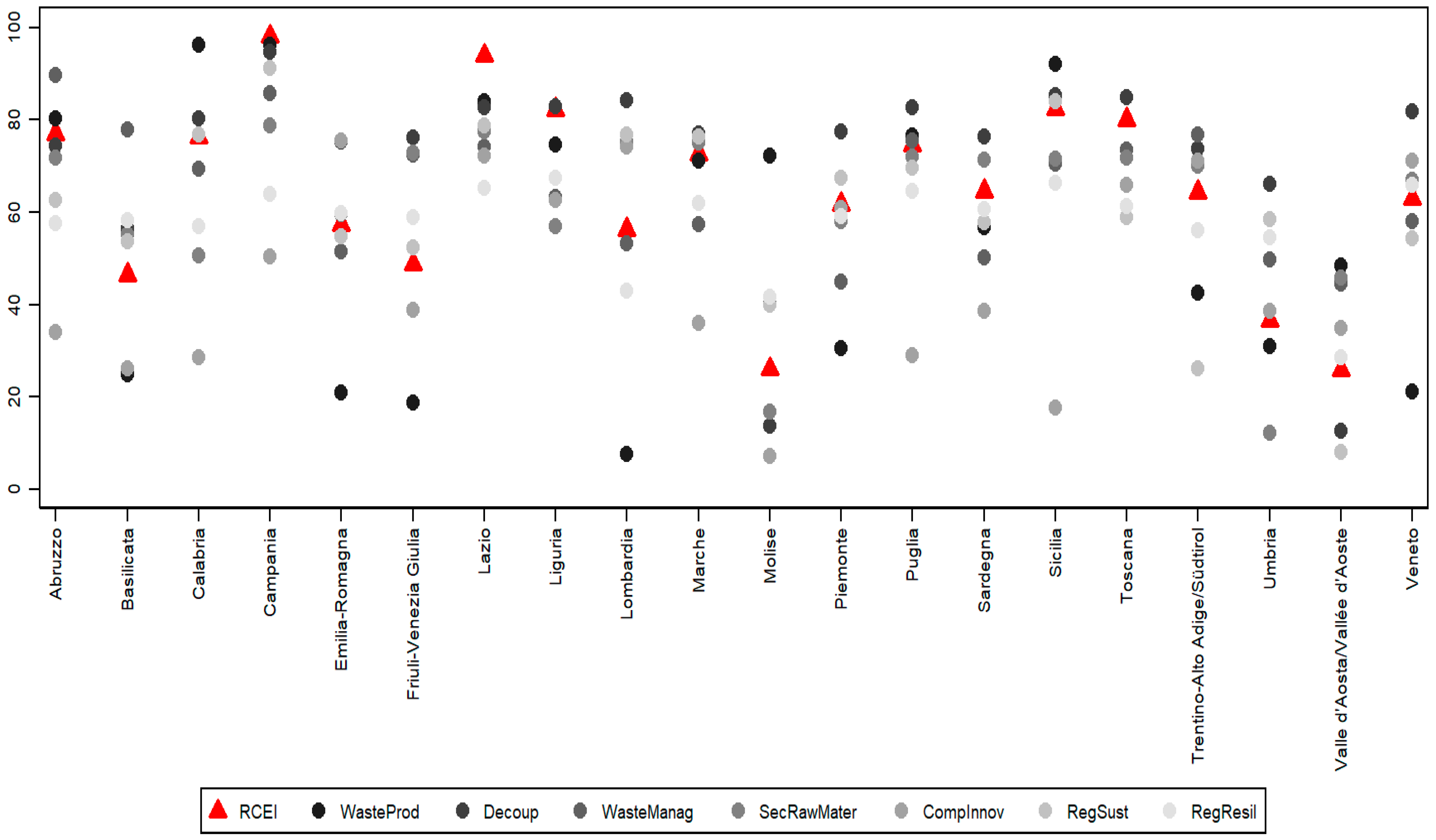

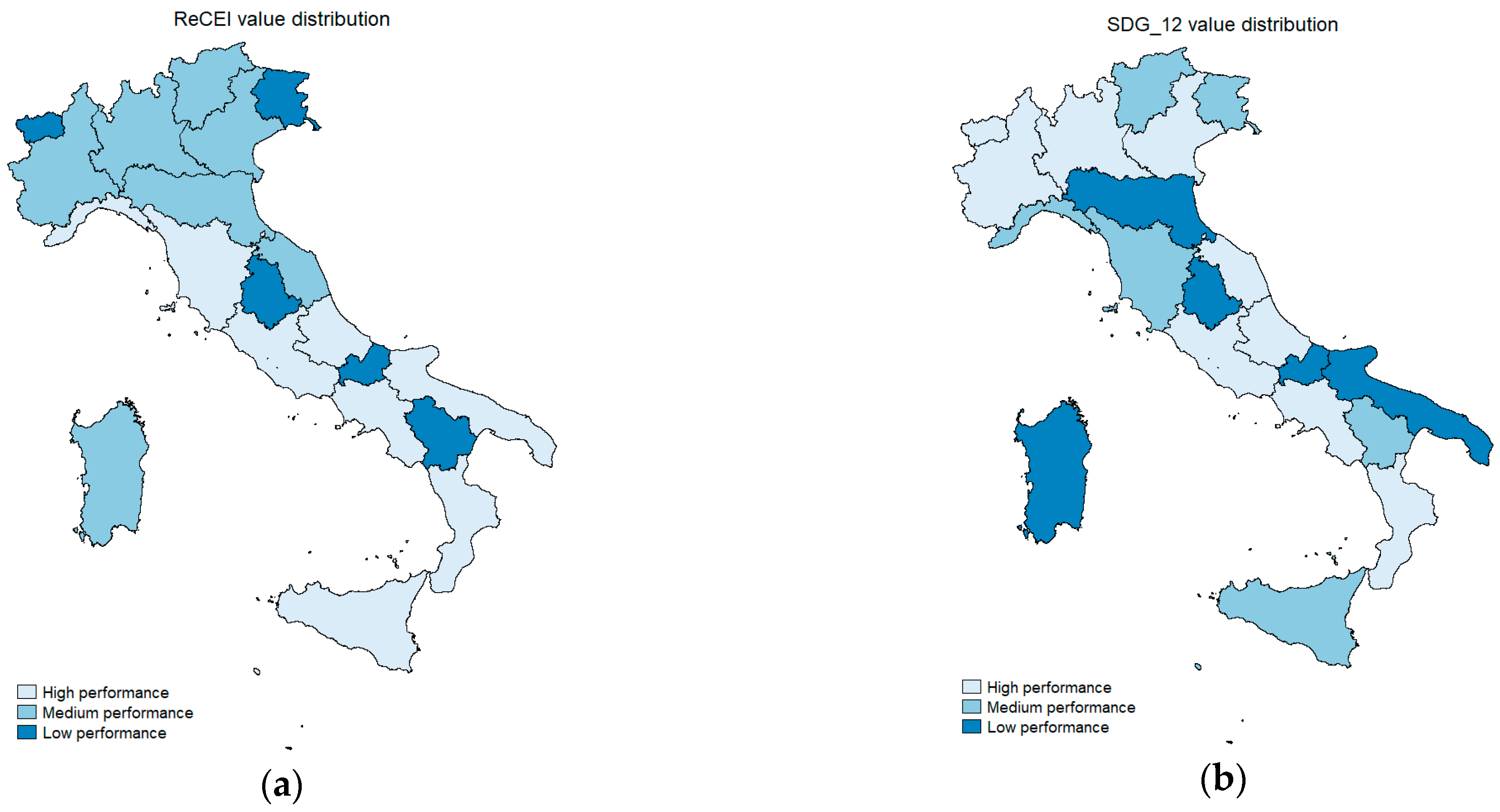

4.1. Regional Circular Economy Performance

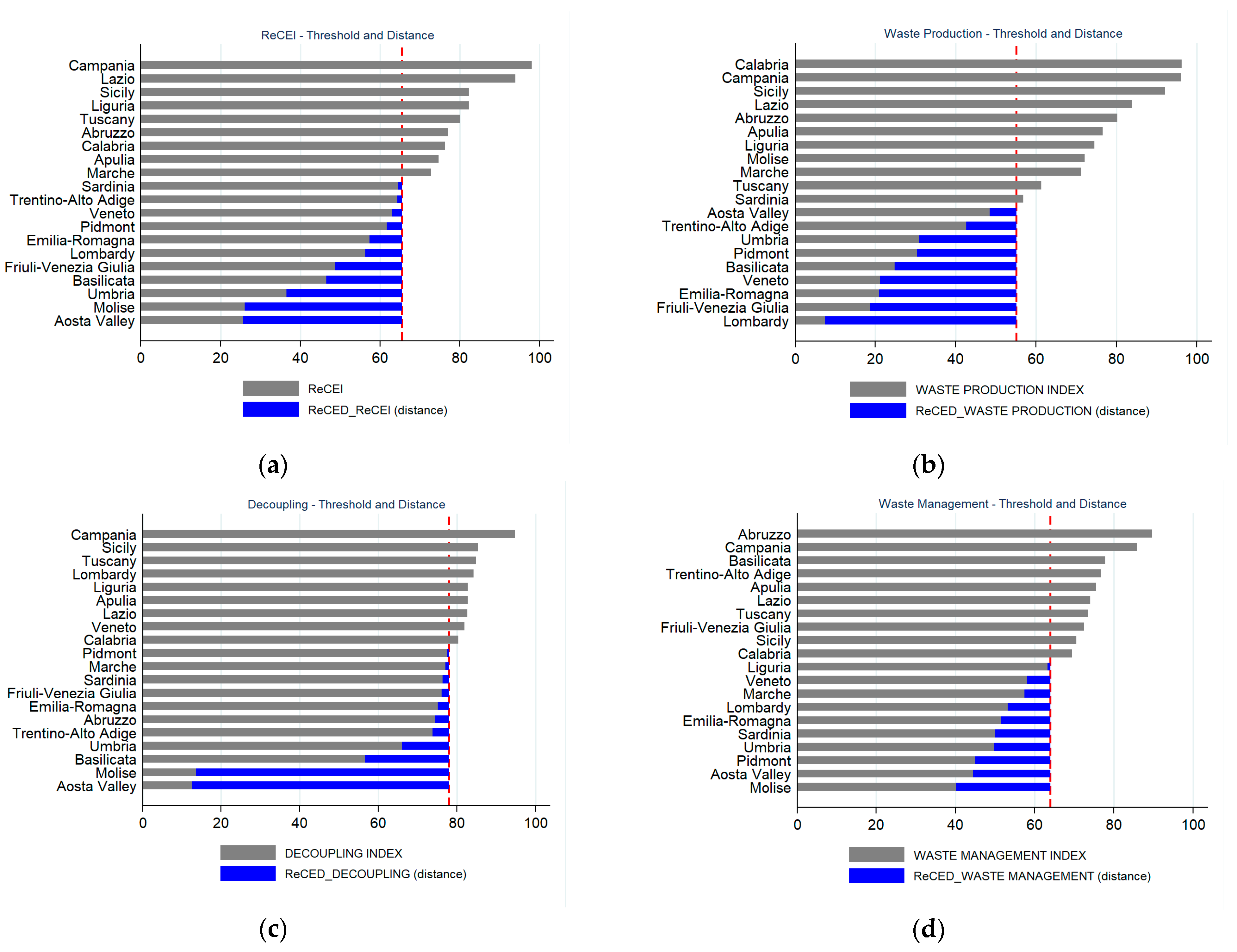

4.2. Regional Circular Economy Disparity

- Scenario 1 (efficiency threshold, z1): establishes a pragmatic benchmark reflecting a satisfactory level of performance, calculated as an “interquartile” average between the first and third quartiles of the distribution.

- Scenario 2 (ideal threshold, z2): sets an aspirational benchmark representing best practice, corresponding to values within the fourth quartile.

5. Robustness Analyses

5.1. Conceptual Validation of ReCEI

5.2. Robustness Analysis of ReCEI

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis of ReCEI

5.4. Sensitivity Analysis of Regional Circular Economy Disparity Index (ReCED)

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Communalities | Initial | Extraction |

|---|---|---|

| Domestic material consumption per capita | 1 | 0.894 |

| Hazard Waste Generation | 1 | 0.918 |

| Waste generation (Urban waste + Special waste) | 1 | 0.831 |

| Waste generation per unit of Value Added | 1 | 0.986 |

| Separate collection of Municipal Waste | 1 | 0.904 |

| Urban waste treated in composting plants | 1 | 0.799 |

| Landfilled Industrial Special Waste | 1 | 0.922 |

| Incinerated Industrial Special Waste | 1 | 0.638 |

| Landfilled urban Waste | 1 | 0.836 |

| Incinerated Urban Waste | 1 | 0.767 |

| Urban waste treated in aerobic and anaerobic plants | 1 | 0.894 |

| Special Waste Recovery | 1 | 0.96 |

| Waste reused as a source of energy | 1 | 0.941 |

| Firms with Energy management system Certification | 1 | 0.623 |

| Firms with Environmental management system | 1 | 0.9 |

| Organization/entrerprises with EMAS registration | 1 | 0.857 |

| Greeb Purchases or Green Public Procurement | 1 | 0.926 |

| Electricity from Renewable sources | 1 | 0.932 |

| Renewable energy share | 1 | 0.925 |

| GHG emission—Industry sector | 1 | 0.949 |

| GHG emission—Transport sector | 1 | 0.922 |

| GHG emission—Agriculture sector | 1 | 0.893 |

| GHG emission—Waste sector | 1 | 0.848 |

| Air quality—PM2.5 | 1 | 0.777 |

| Waste produced from tourism sector | 1 | 0.945 |

| Energy Efficiency Certificates (TEE) | 1 | 0.82 |

| Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. |

| Factors | Eigenvalue | % of Variance | Cumulative % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5451 | 20,965 | 20,965 |

| 2 | 4353 | 16,741 | 37,706 |

| 3 | 3031 | 11,657 | 49,363 |

| 4 | 2955 | 11,367 | 60,730 |

| 5 | 2754 | 10,594 | 71,323 |

| 6 | 2691 | 10,351 | 81,675 |

| 7 | 1373 | 5281 | 86,955 |

| Component Matrix a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Domestic material consumption per capita | −0.246 | −0.295 | −0.682 | −0.246 | 0.405 | 0.201 | −0.127 |

| Hazard Waste Generation | 0.387 | 0.573 | 0.248 | −0.507 | 0.305 | −0.007 | 0.164 |

| Waste generation (Urban waste + Special waste) | 0.579 | 0.59 | −0.037 | 0.063 | −0.138 | 0.152 | 0.318 |

| Waste generation per unit of Value Added | 0.689 | −0.635 | 0.255 | −0.147 | 0.102 | −0.101 | −0.02 |

| Separate collection of Municipal Waste | −0.497 | −0.541 | 0.381 | 0.102 | 0.166 | −0.022 | 0.425 |

| Urban waste treated in composting plants | 0.377 | −0.176 | −0.214 | 0.224 | 0.509 | 0.362 | 0.373 |

| Landfilled Industrial Special Waste | 0.33 | 0.461 | 0.47 | 0.267 | 0.336 | 0.418 | −0.146 |

| Incinerated Industrial Special Waste | 0.172 | 0.027 | 0.232 | 0.728 | −0.09 | −0.125 | −0.02 |

| Landfilled urban Waste | 0.162 | −0.627 | 0.396 | 0.121 | −0.138 | −0.024 | −0.475 |

| Incinerated Urban Waste | 0.184 | 0.335 | 0.305 | 0.192 | 0.366 | −0.579 | 0.15 |

| Urban waste treated in aerobic and anaerobic plants | −0.253 | −0.674 | −0.074 | −0.014 | −0.366 | −0.485 | −0.017 |

| Special Waste Recovery | −0.777 | 0.562 | −0.072 | 0.137 | −0.108 | 0.012 | 0.067 |

| Waste reused as a source of energy | −0.304 | 0.11 | −0.754 | −0.411 | −0.277 | 0.089 | 0.118 |

| Firms with Energy management system Certification | −0.248 | 0.032 | 0.403 | 0.042 | −0.555 | 0.101 | 0.28 |

| Firms with Environmental management system | −0.9 | −0.055 | 0.179 | −0.058 | −0.117 | −0.062 | 0.186 |

| Organization/entrerprises with EMAS registration | −0.507 | −0.279 | 0.216 | −0.495 | 0.276 | 0.362 | −0.153 |

| Greeb Purchases or Green Public Procurement | −0.435 | −0.595 | 0.455 | −0.076 | 0.385 | −0.146 | −0.002 |

| Electricity from Renewable sources | −0.72 | 0.519 | 0.121 | 0.116 | 0.194 | 0.072 | −0.272 |

| Renewable energy share | −0.516 | 0.622 | −0.073 | 0.504 | −0.111 | −0.027 | −0.024 |

| GHG emission—Industry sector | 0.061 | 0.49 | 0.723 | −0.194 | −0.289 | 0.241 | −0.06 |

| GHG emission—Transport sector | 0.774 | −0.437 | 0.17 | −0.227 | −0.215 | −0.028 | 0.071 |

| GHG emission—Agriculture sector | 0.366 | 0.552 | 0.354 | −0.514 | 0.048 | −0.243 | 0.064 |

| GHG emission—Waste sector | 0.372 | 0.699 | −0.129 | −0.152 | −0.145 | −0.166 | −0.364 |

| Air quality—PM2.5 | 0.253 | 0.029 | −0.319 | 0.405 | 0.634 | −0.201 | −0.058 |

| Waste produced from tourism sector | 0.667 | −0.043 | −0.538 | 0.232 | −0.392 | 0.022 | 0.033 |

| Energy Efficiency Certificates (TEE) | 0.2 | −0.488 | 0.169 | 0.342 | −0.258 | 0.573 | −0.034 |

| Rotated Component Matrix a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Domestic material consumption per capita | 0.073 | 0.11 | −0.204 | −0.16 | −0.614 | −0.655 | 0.054 |

| Hazard Waste Generation | −0.136 | −0.148 | 0.766 | 0.493 | 0.07 | −0.133 | 0.159 |

| Waste generation (Urban waste + Special waste) | −0.081 | −0.624 | 0.249 | 0.363 | 0.163 | 0.172 | 0.43 |

| Waste generation per unit of Value Added | −0.965 | 0.131 | −0.008 | 0.006 | −0.095 | 0.145 | −0.084 |

| Separate collection of Municipal Waste | 0.002 | 0.857 | −0.192 | −0.196 | 0.145 | 0.126 | 0.241 |

| Urban waste treated in composting plants | −0.295 | 0.043 | −0.209 | 0.331 | −0.472 | 0.02 | 0.577 |

| Landfilled Industrial Special Waste | 0.034 | −0.08 | 0.057 | 0.901 | −0.008 | 0.316 | −0.021 |

| Incinerated Industrial Special Waste | 0.043 | −0.098 | −0.264 | 0.071 | −0.01 | 0.743 | −0.01 |

| Landfilled urban Waste | −0.499 | 0.259 | −0.365 | −0.03 | 0.083 | 0.22 | −0.575 |

| Incinerated Urban Waste | 0.051 | 0.075 | 0.596 | 0.055 | −0.197 | 0.598 | 0.06 |

| Urban waste treated in aerobic and anaerobic plants | −0.206 | 0.275 | −0.202 | −0.82 | 0.104 | 0.06 | −0.221 |

| Special Waste Recovery | 0.952 | 0.052 | 0.058 | −0.051 | 0.198 | −0.058 | 0.052 |

| Waste reused as a source of energy | 0.296 | −0.331 | −0.026 | −0.435 | −0.013 | −0.716 | 0.203 |

| Local units with Energy management system Certification | 0.128 | 0.115 | −0.128 | −0.082 | 0.736 | 0.134 | 0.104 |

| Local units with Environmental management system | 0.584 | 0.579 | −0.051 | −0.302 | 0.335 | −0.133 | 0.005 |

| Organization/entrerprises with EMAS registration | 0.063 | 0.644 | −0.047 | 0.194 | 0.073 | −0.59 | −0.211 |

| Greeb Purchases or Green Public Procurement | −0.113 | 0.926 | −0.032 | −0.106 | −0.07 | 0.048 | −0.19 |

| Electricity from Renewable sources | 0.868 | 0.21 | 0.094 | 0.237 | 0.002 | −0.04 | −0.26 |

| Renewable energy share | 0.894 | −0.168 | −0.066 | 0.045 | 0.067 | 0.292 | 0.03 |

| GHG emission—Industry sector | 0.07 | −0.038 | 0.274 | 0.548 | 0.723 | 0.107 | −0.183 |

| GHG emission—Transport sector | −0.929 | −0.17 | 0.011 | −0.025 | 0.159 | 0.063 | 0.013 |

| GHG emission—Agriculture sector | −0.154 | −0.199 | 0.826 | 0.281 | 0.259 | −0.004 | −0.042 |

| GHG emission—Waste sector | 0.123 | −0.714 | 0.45 | 0.202 | 0.003 | 0.012 | −0.283 |

| Air quality—PM2.5 | 0.001 | −0.071 | 0.047 | 0.094 | −0.808 | 0.305 | 0.125 |

| Waste produced from tourism sector | −0.379 | −0.787 | −0.278 | −0.198 | −0.125 | 0.094 | 0.201 |

| Energy Efficiency Certificates (TEE) | −0.366 | 0.05 | −0.761 | 0.225 | 0.21 | 0.092 | 0.034 |

Appendix B

| Dimension: Production and Consumption (A) | ||

| Waste production (Pillar 1) | U.M. | Source |

| Hazardous waste generation | tonnes per capita | ISTAT |

| Waste generation (Urban waste + Special waste) | tonnes per capita | ISPRA |

| Decoupling (Pillar 2) | ||

| Domestic material consumption per capita | tonnes per capita | ISTAT |

| Waste generation per unit of Value Added | tonnes per thousand euros | ARDECO |

| Dimension: Waste | ||

| Waste management (Pillar 3) | U.M. | Source |

| Separate collection of municipal waste | kg per capita | ISTAT |

| Urban waste treated in composting plants | kg per capita | ISPRA |

| Landfilled industrial special waste | kg per capita | ISPRA |

| Landfilled urban waste | kg per capita | ISPRA |

| Incinerated industrial special waste | kg per capita | ISPRA |

| Incinerated urban waste | kg per capita | ISPRA |

| Urban waste treated in aerobic and anaerobic plants | kg per capita | ISPRA |

| Dimension: Secondary raw materials | ||

| Waste recovery level (Pillar 4) | U.M. | Source |

| Special waste recovery | tonnes per 1000 inhabitants | ISPRA |

| Waste reused as a source of energy | tonnes per 1000 inhabitants | ISPRA |

| Dimension: Competitiveness and innovation | ||

| Sustainable innovation (Pillar 5) | U.M. | Source |

| Local units with Energy management system Certification (UNI CEI EN ISO 50001) | Number per 1000 inhabitants | ISTAT |

| Local units with Environmental management system Certification (UNI EN ISO 14001) | Number per 1000 inhabitants | ISTAT |

| Organizations/enterprises with EMAS registration | Number per 1000 inhabitants | ISTAT |

| Green purchases or Green Public Procurement | % | ISTAT |

| Dimension: Regional sustainability and resilience | ||

| Environmental sustainability (Pillar 6) | U.M. | Source |

| GHG emission Industry sector | kt CO2 eq per capita | ARDECO |

| GHG emissions Transport sector | kt CO2 eq per capita | ARDECO |

| GHG emissions Agriculture sector | kt CO2 eq per capita | ARDECO |

| GHG emissions Waste sector | kt CO2 eq per capita | ARDECO |

| Air quality- PM2.5 | % | ISTAT |

| Waste produced by tourism sector | kg per capita | ISTAT |

| Environmental Resilience (Pillar 7) | ||

| Electricity from renewable sources | % | ISTAT |

| Renewable energy share | % | ISTAT |

| Energy Efficiency Certificates (TEE) | Number per 1000 inhabitants | GSE |

Appendix C

Appendix C.1. Missing Data

- For the variables in dimension Production and consumption, there are no critical observations.

- For the variables in the dimension Waste, critical issues are detected for variables “Incinerated Urban Waste”, “Urban waste treated in composting plants”, and “Urban waste treated in aerobic and anaerobic plants”, for which the within-panel minimum value is negative. Further inspection suggests that, for the variable “Incinerated Urban Waste”, there are 4 out of 20 regions that do not present data (have zero values). The lack of specific data on incinerators for special waste in Liguria, Marche, Umbria and Valle d’Aosta is mainly due to the absence of active incineration plants in these regions. In particular, the Valle d’Aosta and Umbria manage special waste mainly through recovery or disposal facilities outside the region [75], while Liguria and Marche have no operational facilities yet and are considering or planning alternative solutions. In addition, the management of special waste in these regions is subject to regulations favoring non-thermal recovery and treatment, limiting the availability of data on specific incinerators [75].

- For the variables in the dimension Secondary Raw Materials, there is one critical observation for the variable “Waste reused as a source of energy” for which the within- panel minimum value is negative. In this case, there is 1 out of 20 regions that does not present data (has zero values). This is the Valle d’Aosta region, where there are no energy recovery plants [75].

- For the variables in the dimensions Competitiveness and Innovation and Regional sustainability and resilience, there are no critical observations.

Appendix C.2. Checking for Structural Breaks

- For the variables in the dimension Production and Consumption, there are no significantly critical observations. However, for the variable “Waste generation (Urban waste + Special waste)”, two aspects are worth noticing: one region (Valle d’Aosta; id = 19) reports a very high initial value. This can be explained by the “scale” effect and reduced population. In Valle d’Aosta, even modest absolute variations in the waste produced (for example, a few thousand tons) result in very high per capita variations, given the low number of residents. Moreover, about half of the regions in the sample show a sudden increase in the variable in the aftermath of COVID-19 (year 2021). The graph below (Figure A2) shows the distribution over time of the variable “Waste generation (Urban waste + Special waste)”, as calculated on average for Italy as a whole. The structural break, identified for this variable, mainly reflects the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused a sharp reduction in waste production due to lockdown, closure of activities and changes in consumption behavior [117,118].

- For the variables in the dimension Secondary Raw Materials, there are no critical observations.

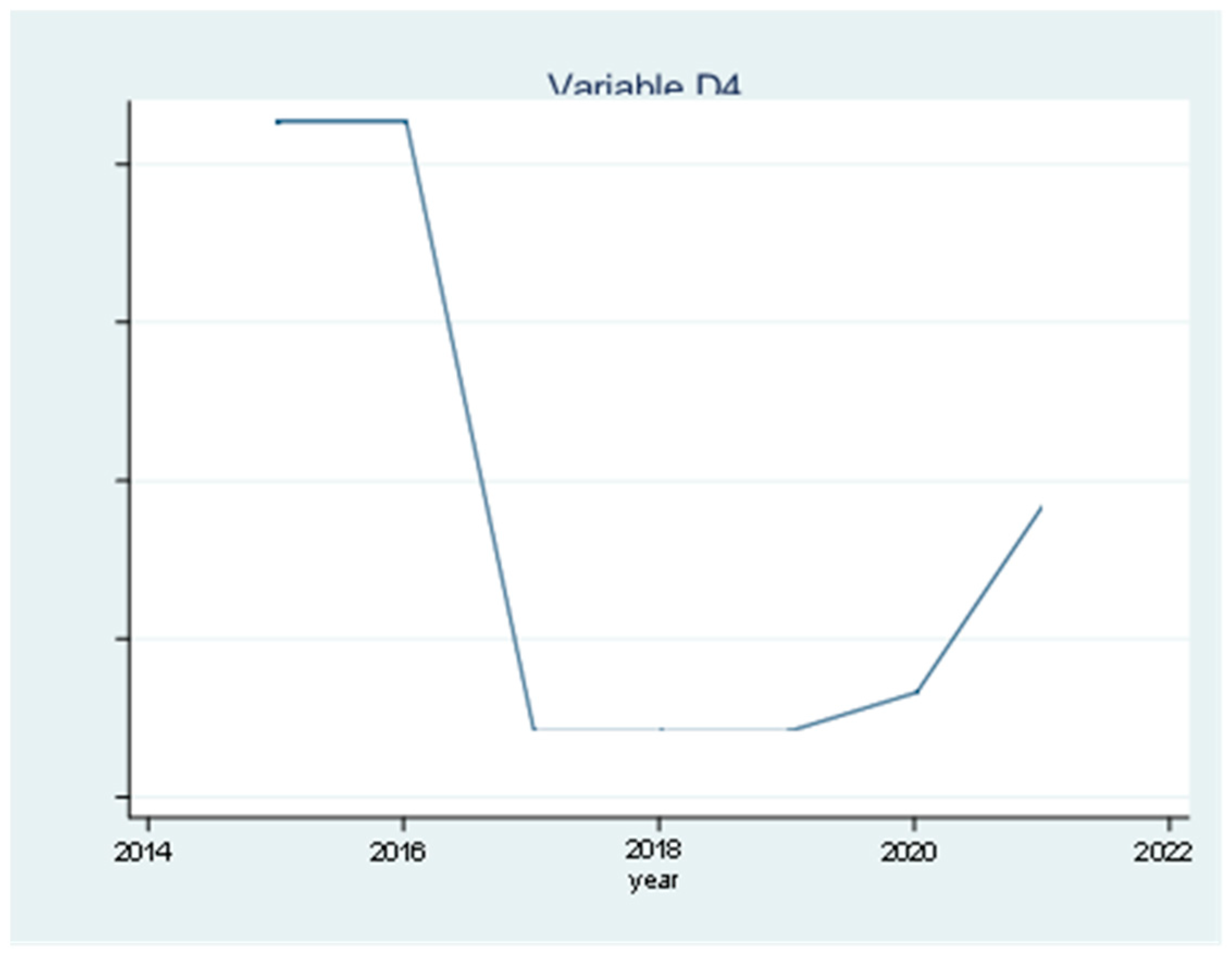

- For the variables in the macro-category Competitiveness and Innovation, critical points are detected for variable “Greeb Purchases or Green Public Procurement” (D4). As reported in Figure A5, the variable shows, for all the regions in the sample, a sudden downward shift located at the year 2016. This decrease can be explained by the entry into force of the new Procurement Code (D.Lgs. 50/2016), which has introduced new obligations and more complex procedures for the adoption of CAMs. This has led to a transitional adaptation effect, with a temporary suspension or reduction in green purchases by public administrations, pending clarification and training.

- For the variables in the dimension “Regional sustainability and resilience”, there are no critical observations

Impact of the COVID-19 Period on the ReCEI Index and Its Pillars

| Regions | ReCEI | WastePro | Decoup | WasteManag | SecRawMater | CompInnov | RegSust | RegResil |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abruzzo | −2.38 | 1.67 | −3.27 | −2.42 | 5.39 | −11.99 | −2.47 | 21.76 |

| Basilicata | 11.28 | 37.75 | 2.26 | −7.69 | 24.57 | 2.57 | −16.28 | 4.29 |

| Calabria | −0.77 | −1.53 | −2.61 | 3.09 | 24.94 | 9.65 | −1.20 | 12.14 |

| Campania | −0.30 | 0.37 | −1.32 | 2.16 | 14.80 | −0.52 | −3.51 | 26.08 |

| Emilia-Romagna | 11.12 | −29.43 | −6.52 | −13.56 | −7.26 | 5.13 | −1.31 | 30.71 |

| Friuli-Venezia Giulia | 26.41 | 30.97 | −4.72 | 3.09 | −7.24 | −18.54 | −3.70 | 26.65 |

| Lazio | 2.82 | −1.27 | −6.33 | 9.97 | 15.06 | 0.39 | 0.33 | 31.42 |

| Liguria | −0.32 | −0.05 | −1.98 | 9.04 | −1.37 | 2.07 | −7.10 | 25.25 |

| Lombardy | 21.17 | −10.01 | −4.20 | −13.29 | −1.65 | 2.60 | 8.91 | 40.00 |

| Marche | 1.55 | −0.42 | −5.82 | 10.31 | −5.63 | −4.27 | −2.22 | 23.66 |

| Molise | 8.53 | 0.89 | −3.47 | 14.46 | −8.08 | −83.78 | −8.48 | 4.58 |

| Piedmont | 7.31 | −4.44 | 0.64 | 2.90 | −5.43 | −5.18 | 0.53 | 21.33 |

| Apulia | 7.75 | 6.52 | −0.37 | 6.54 | 8.27 | −1.25 | −2.69 | 25.79 |

| Sardinia | 4.27 | −5.63 | 3.33 | −18.83 | 22.98 | 9.60 | −3.01 | 24.22 |

| Sicily | 2.95 | 0.26 | −2.70 | 2.74 | 10.64 | 19.34 | −2.72 | 29.66 |

| Tuscany | 0.46 | −1.62 | −3.34 | 6.60 | 16.39 | −12.23 | −7.58 | 27.39 |

| Trentino-Alto Adige | −2.29 | 11.01 | 2.84 | 0.05 | −1.10 | −10.94 | −14.72 | 15.65 |

| Umbria | 40.00 | −5.87 | −1.16 | 19.48 | 19.72 | −12.40 | −0.58 | 24.29 |

| Valle d’Aosta | −59.68 | −12.56 | 2.79 | −31.37 | 11.79 | −28.41 | 40.00 | −100.00 |

| Veneto | 8.76 | −10.15 | −4.07 | −16.49 | 2.92 | 0.52 | −3.08 | 28.63 |

References

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy—A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. A New Circular Economy Action Plan for a Cleaner and More Competitive Europe; COM (2020) 98 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium; Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. European Semester: 2023 Country Reports and Recommendations; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium; Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Crescenzi, R.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. Innovation and Regional Growth in the European Union; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, L.; Poelman, H.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. The geography of EU discontent. Reg. Stud. 2020, 54, 737–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, A.; Ashton, W.; Teixeira, C.; Lyon, E.; Pereira, J. Infrastructuring the circular economy. Energies 2020, 13, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Circular Economy in Cities and Regions: Synthesis Report; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Aldieri, L.; Gatto, A.; Vinci, C.P. Evaluation of energy resilience and adaptation policies: An energy efficiency analysis. Energy Policy 2021, 157, 112505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barca, F.; McCann, P.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. The case for regional development intervention: Place-based versus place-neutral approaches. J. Reg. Sci. 2012, 52, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iammarino, S.; Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Storper, M. Regional inequality in Europe: Evidence, theory and policy implications. J. Econ. Geogr. 2019, 19, 273–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capello, R.; Caragliu, A. Regional growth and disparities in a post-COVID Europe: A new normality scenario. J. Reg. Sci. 2021, 61, 710–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camagni, R.; Capello, R. Regional competitiveness and territorial capital: A conceptual approach and empirical evidence from the European Union. Reg. Stud. 2013, 47, 1383–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamash, A.; Iyiola, K.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. The Role of Circular Economy Entrepreneurship, Cleaner Production, and Green Government Subsidy for Achieving Sustainability Goals in Business Performance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palea, V.; Migliavacca, A.; Gordano, S. Scaling up the transition: The role of corporate governance mechanisms in promoting circular economy strategies. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 349, 119544. [Google Scholar]

- Dąbrowski, M.; Williams, J.; Van den Berghe, K.; Van Bueren, E. 1. Circular regions and cities: Towards a spatial perspective on circular economy. Reg. Stud. Policy Impact Books 2024, 6, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjanović, M.; Williams, J. Mapping the emergence of the circular economy within the governance paths of shrinking cities and regions: A comparative study of Parkstad Limburg (NL) and Satakunta (FI). Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2024, 17, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur-Wierzbicka, E. Circular economy: Advancement of European Union countries. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, G.; Pozzi, C.; Gurrieri, A.R.; Mele, M.; Costantiello, A.; Magazzino, C. The role of circular economy in EU entrepreneurship: A deep learning experiment. J. Econ. Asymmetries 2024, 30, e00372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strom, P.; Hermelin, B. An economic geography approach to the implementation of circular economy-comparing three examples of industry-specific networks in West Sweden. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2023, 16, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mazziotta, M.; Pareto, A. A non-compensatory composite index for measuring well-being over time. Cogito. Multidiscip. Res. J. 2013, 5, 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Saisana, M.; Tarantola, S. State-of-the-Art Report on Current Methodologies and Practices for Composite Indicator Development; European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Institute for the Protection and the Security of the Citizen, Technological and Economic Risk Management Unit: Ispra, Italy, 2002; Volume 214, pp. 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Poverty: An ordinal approach to measurement. Econometrics 1976, 44, 219–231. [Google Scholar]

- Arbolino, R.; Boffardi, R.; De Simone, L.; Ioppolo, G. Who achieves the efficiency? A new approach to measure “local energy efficiency”. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 110, 105875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbolino, R.; Boffardi, R.; Ioppolo, G.; Lantz, T.L.; Rosa, P. Evaluating industrial sustainability in OECD countries: A cross-country comparison. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 331, 129773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulant, J.; Brezzi, M.; Veneri, P. Income Levels and Inequality in Metropolitan Areas; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R.; Sunley, P. On the notion of regional economic resilience: Conceptualization and explanation. J. Econ. Geogr. 2015, 15, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it). Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2018, 11, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G. Development of a general sustainability indicator for renewable energy systems: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 31, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioppolo, G.; Heijungs, R.; Cucurachi, S.; Salomone, R.; Kleijn, R. Urban Metabolism: Many open questions for future answers. In Pathways to Environmental Sustainability: Methodologies and Experiences; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Fitjar, R.D.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. Innovating in the periphery: Firms, values and innovation in Southwest Norway. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2011, 19, 555–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschma, R.A.; Frenken, K. Why is economic geography not an evolutionary science? Towards an evolutionary economic geography. J. Econ. Geogr. 2006, 6, 273–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balland, P.A.; Boschma, R.; Crespo, J.; Rigby, D.L. Smart specialization policy in the European Union: Relatedness, knowledge complexity and regional diversification. Reg. Stud. 2020, 54, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, D. Sustainability entrepreneurs, ecopreneurs and the development of a sustainable economy. Greener Manag. Int. 2006, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrysson, M.; Nuur, C. The role of institutions in creating circular economy pathways for regional development. J. Environ. Dev. 2021, 30, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cader, J.; Koneczna, R.; Marciniak, A. Indicators for a circular economy in a regional context: An approach based on Wielkopolska region, Poland. Environ. Manag. 2024, 73, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, C.; Bianchi, M.; Pallaske, G.; Bassi, A.M. Towards a territorial definition of a circular economy: Exploring the role of territorial factors in closed-loop systems. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2021, 29, 1438–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESPON. CIRCTER—Circular Economy and Territorial Consequences Applied Research; Final Report; ESPON: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Heurkens, E.; Dąbrowski, M. Circling the square: Governance of the circular economy transition in the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area. Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2020, 27, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, M.; Longo, M.; Zanni, S. Circular economy in Italian SMEs: A multi-method study. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide; OECD: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Murty, H.R.; Gupta, S.K.; Dikshit, A.K. An overview of sustainability assessment methodologies. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 15, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, G.M.; Rao, K.V. A composite index to explain variations in poverty, health, nutritional status and standard of living: Use of multivariate statistical methods. Public Health 2007, 121, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotelling, H. Analysis of a complex of statistical variables into principal components. J. Educ. Psychol. 1933, 24, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T. Choosing a subset of principal components or variables. In Principal Component Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 92–114. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, J.E. A User’s Guide to Principal Components; John Wiley Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti, G.; Scarpetta, S.; Boylaud, O. Summary Indicators of Product Market Regulation with an Extension to Employment Protection Legislation; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubert, M.; Vandervieren, E. An adjusted boxplot for skewed distributions. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2008, 52, 5186–5201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, R. How significant is a boxplot outlier? J. Stat. Educ. 2011, 19, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.B. Multidimensional deprivation: Contrasting social welfare and counting approaches. J. Econ. Inequal. 2003, 1, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkire, S.; Santos, M.E. Acute multidimensional poverty: A new index for developing countries. In Proceedings of the German Development Economics Conference, Berlin, Germany, 17–18 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban, J.M.; Ray, D. On the measurement of polarization. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1994, 62, 819–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, S.P.; Van Kerm, P. The Measurement of Economic Inequality; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Equality of What? In The Tanner Lectures on Human Values; McMurrin, S., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1979; pp. 195–220. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Kowalski, M.; Haas, W.; Wiedenhofer, D.; Weisz, U.; Pallua, I.; Possanner, N.; Behrens, A.; Serio, G.; Alessi, M.; Weis, E. Socio-Ecological Transitions: Definition, Dynamics and Related Global Scenarios; Institute for Social Ecology-AAU, Centre for European Policy Studies: Vienna, Austria; Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, P.; Sassanelli, C.; Terzi, S. Towards Circular Business Models: A systematic literature review on classification frameworks and archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 236, 117696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camana, D.; Manzardo, A.; Toniolo, S.; Gallo, F.; Scipioni, A. Assessing environmental sustainability of local waste management policies in Italy from a circular economy perspective. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 613–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.; Skene, K.; Haynes, K. The circular economy: An interdisciplinary exploration of the concept and application in a global context. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Isle of Wight, UK, 2012; Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/ (accessed on 1 January 2013).

- Lieder, M.; Rashid, A. Towards circular economy implementation: A comprehensive review in context of manufacturing industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 115, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The OECD RE-CIRCLE Project: Building Circular Economy Indicators; OECD Reports; OECD: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. OECD Regional Well-Being; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, N.; Rodrigues, R.; Antunes, T. Circular Economy Models for Reducing Food Waste and Enhancing Sustainability: A Case Study of Cooperative X. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2025, 5, 3529–3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraga, G.; Huysveld, S.; Mathieux, F.; Blengini, G.A.; Alaerts, L.; Van Acker, K.; de Meester, S.; Dewulf, J. Circular economy indicators: What do they measure? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzanti, M.; Zoboli, R. Waste generation, waste disposal and policy effectiveness: Evidence on decoupling from the European Union. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2008, 52, 1221–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolli, F.; Johnstone, N.; Söderholm, P. Resolving failures in recycling markets: The role of technological innovation. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2012, 14, 261–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Decoupling Indicators—Monitoring Resource Efficiency in Europe; EEA Report; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wiedenhofer, D.; Wieland, H.; Leipold, S.; Aoki-Suzuki, C.; Edelenbosch, O.Y.; Zanon-Zotin, M.; Kaufmann, L.; Fortes, P.; Haas, W.; Streeck, J. Can the Circular Economy Save the Climate? Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2025, 50, 563–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyravi, B.; Peleckis, K.; Limba, T.; Peleckienė, V. The circular economy practices in the European Union: Eco-innovation and sustainable development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusmerotti, N.M.; Testa, F.; Corsini, F.; Pretner, G.; Iraldo, F. Drivers and approaches to the circular economy in manufacturing firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 230, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbinati, A.; Chiaroni, D.; Chiesa, V. Towards a new taxonomy of circular economy business models. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakhar, S.K.; Mangla, S.K.; Luthra, S.; Kusi-Sarpong, S. When stakeholder pressure drives the circular economy: Measuring the mediating role of innovation capabilities. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 904–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberl, H.; Wiedenhofer, D.; Virág, D.; Kalt, G.; Plank, B.; Brockway, P.; Fishman, T.; Hausknost, D.; Krausmann, F.; Leon-Gruchalski, B.; et al. A systematic review of the evidence on decoupling of GDP, resource use and GHG emissions, part II: Synthesizing the insights. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 065003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISPRA. Rapporto Rifiuti Urbani—Edizione 2022; Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale: Roma, Italy, 2022.

- Fankhauser, S.; Averchenkova, A.; Finnegan, J.J. 10 years of the UK Climate Change Act. Clim. Policy 2018, 18, 1194–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Feldman, M.P. Knowledge spillovers and the geography of innovation. In Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 4, pp. 2713–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisetti, C.; Quatraro, F. Green technologies and environmental productivity: A cross-sectoral analysis of direct and indirect effects in Italian regions. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 132, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cainelli, G.; D’Amato, A.; Mazzanti, M. Resource efficient eco-innovations for a circular economy: Evidence from EU firms. Res. Policy 2020, 49, 103827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinsel, S.R.; Markard, J.; Hoffmann, V.H. How deployment policies affect innovation in complementary technologies—Evidence from the German energy transition. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 161, 120274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, V.; Crespi, F.; Marin, G.; Paglialunga, E. Eco-innovation, sustainable supply chains and environmental performance in European industries. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 155, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bănică, A.; Ţigănaşu, R.; Nijkamp, P.; Kourtit, K. Institutional quality in green and digital transition of EU regions–A recovery and resilience analysis. Glob. Chall. 2024, 8, 2400031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Ulgiati, S. Circular economy transition in Italy. Achievements, perspectives and constraints. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, V.D.; Maria, E.D.; Micelli, S. Environmental strategies, upgrading and competitive advantage in global value chains. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013, 22, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonioli, D.; Chioatto, E.; Mazzanti, M. Innovations and the circular economy: A national and regional perspective. Insights Into Reg. Dev. 2022, 4, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testa, F.; Iraldo, F.; Frey, M. The effect of environmental regulation on firms’ competitive performance: The case of the building construction sector in some EU regions. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 2136–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I.; Falcone, P.M.; Imbert, E.; Morone, P. Exploring regional transitions to the bioeconomy using a socio-economic indicator: The case of Italy. Econ. Politica 2022, 39, 989–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsova, S.; Genovese, A.; Ketikidis, P.H. Implementing circular economy in a regional context: A systematic literature review and a research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 368, 133117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, M.; De los Rios, C.; Rowe, Z.; Charnley, F. A conceptual framework for circular design. Sustainability 2016, 8, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, P.; Rutqvist, J. Waste to Wealth: The Circular Economy Advantage; Harvard Business Review Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmykova, Y.; Sadagopan, M.; Rosado, L. Circular economy–From review of theories and practices to development of implementation tools. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Piscicelli, L.; Bour, R.; Kostense-Smit, E.; Muller, J.; Huibrechtse-Truijens, A.; Hekkert, M. Barriers to the circular economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU). Ecol. Econ. 2018, 150, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, V.; Mazzanti, M.; Montini, A. Environmental performance, innovation and spillovers. Evidence from a regional NAMEA. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 89, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.A. Circular economy at the micro level: A dynamic view of incumbents’ struggles and challenges in the textile industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 833–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Sarkis, J.; Bleischwitz, R. How to globalize the circular economy. Nature 2019, 565, 153–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. Prosperity Without Growth: Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Di Cataldo, M. Quality of government and innovative performance in Europe. J. Econ. Geogr. 2015, 15, 673–706. [Google Scholar]

- Horbach, J.; Rammer, C.; Rennings, K. Determinants of eco-innovations. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 78, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, C.; Hazlett, C. Making sense of sensitivity: Extending omitted variable bias. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2020, 82, 39–67. [Google Scholar]

- Dizdaroglu, D. The role of indicator-based sustainability assessment in policy and the decision-making process: A review and outlook. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1018. [Google Scholar]

- Saisana, M.; Saltelli, A.; Tarantola, S. Uncertainty and sensitivity analysis techniques as tools for the quality assessment of composite indicators. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 2005, 168, 307–323. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Monitoring Framework for the Circular Economy; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium; Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Circular Economy Network; ENEA. Circularity Gap Report Italia 2024; ENEA: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bocci, L.; D’Urso, P.; Vicari, D.; Vitale, V. A regression tree-based analysis of the European regional competitiveness. Soc. Indic. Res. 2024, 173, 137–167. [Google Scholar]

- Arbolino, R.; Lantz, T.L.; Napolitano, O. Assessing the impact of special economic zones on regional growth through a comparison among EU countries. Reg. Stud. 2023, 57, 1069–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, S.; Ishizaka, A.; Tasiou, M.; Torrisi, G. On the methodological framework of composite indices: A review of the issues of weighting, aggregation, and robustness. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 141, 61–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, S.P.; Heaney, A. Composite outcome measurement in clinical research: The triumph of illusion over reality? J. Med. Econ. 2020, 23, 1196–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuc-Czarnecka, M.; Piano, S.L.; Saltelli, A. Quantitative storytelling in the making of a composite indicator. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 149, 775–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Global Economic Prospects, June 2017: A Fragile Recovery; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbolino, R.; Boffardi, R.; De Simone, L.; Ioppolo, G.; Lopes, A. Circular economy convergence across European Union: Evidence on the role policy diffusion and domestic mechanisms. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2024, 96, 102051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbia, G. Spatial Data Configuration in Statistical Analysis of Regional Economic and Related Problems; Springer Science Business Media: Luxembourg, 2012; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, D.G.; Butler, D.G. Statistical validation. Ecol. Model. 1993, 68, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, M.; Cordella, M.; Menger, P. Regional monitoring frameworks for the circular economy: Implications from a territorial perspective. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2023, 31, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditzen, J.; Karavias, Y.; Westerlund, J. Testing and estimating structural breaks in time series and panel data in Stata. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.14550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditzen, J.; Karavias, Y.; Westerlund, J. Multiple structural breaks in interactive effects panel data models. J. Appl. Econom. 2025, 40, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aue, A.; Horváth, L. Structural breaks in time series. J. Time Ser. Anal. 2013, 34, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Monserrate, M.A.; Ruano, M.A.; Sanchez-Alcalde, L. Indirect effects of COVID-19 on the environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, M.; Oskoei, V.; Jonidi Jafari, A.; Farzadkia, M.; Hasham Firooz, M.; Abdollahinejad, B.; Torkashvand, J. Municipal solid waste management during COVID-19 pandemic: Effects and repercussions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 32200–32209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agovino, M.; Garofalo, A.; Mariani, A. Effects of environmental regulation on separate waste collection dynamics: Empirical evidence from Italy. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 124, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISPRA. Rapporto Rifiuti Urbani—Edizione 2017; Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale: Roma, Italy, 2017.

| Variable | U.M. | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Waste Generation | tonnes per capita | 140 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.34 |

| Waste generation (Urban waste + Special waste) | tonnes per capita | 140 | 2.95 | 0.92 | 1.41 | 5.48 |

| Domestic material consumption per capita | tonnes per capita | 140 | 8.98 | 3.29 | 3.70 | 16.90 |

| Waste generation per unit of Value Added | tonnes per thousand euros | 140 | 122.68 | 173.72 | 7.90 | 729.22 |

| Separate collection of Municipal Waste | kg per capita | 160 | 284.42 | 84.37 | 59.74 | 468.93 |

| Urban waste treated in composting plants | kg per capita | 140 | 63.99 | 41.27 | 0.00 | 214.74 |

| Incinerated Urban Waste | kg per capita | 140 | 70.44 | 76.54 | 0.00 | 299.73 |

| Landfilled Industrial Special Waste | kg per capita | 140 | 225.78 | 202.79 | 0.00 | 862.04 |

| Landfilled urban Waste | kg per capita | 140 | 238.49 | 179.91 | 0.00 | 654.91 |

| Incinerated Industrial Special Waste | kg per capita | 140 | 16.34 | 21.76 | 0.00 | 83.17 |

| Urban waste treated in aerobic and anaerobic plants | kg per capita | 140 | 42.18 | 66.46 | 0.00 | 287.77 |

| Special Waste Recovery | tonnes per 1000 inhabitants | 140 | 80.20 | 19.18 | 41.00 | 149.79 |

| Waste reused as a source of energy | tonnes per 1000 inhabitants | 140 | 1.62 | 1.68 | 0.00 | 6.92 |

| Firms with Energy management system Certification | Number per 1000 inhabitants | 140 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.13 |

| Firms with Environmental management system Certification | Number per 1000 inhabitants | 140 | 0.39 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.94 |

| Organization/entrerprises with EMAS registration | Number per 1000 inhabitants | 140 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.09 |

| Greeb Purchases or Green Public Procurement | % | 140 | 37.62 | 18.20 | 10.70 | 69.90 |

| GHG emission—Industry sector | kt CO2 eq per capita | 140 | 1.55 | 0.85 | 0.38 | 3.65 |

| GHG emission—Transport sector | kt CO2 eq per capita | 140 | 2.11 | 0.92 | 0.78 | 5.05 |

| GHG emission—Agriculture sector | kt CO2 eq per capita | 140 | 0.51 | 0.35 | 0.06 | 1.92 |

| GHG emission—Waste sector | kt CO2 eq per capita | 140 | 0.25 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.49 |

| Air quality—PM2.5 | % | 140 | 78.96 | 20.04 | 6.10 | 100.00 |

| Waste produced from tourism sector | kg per capita | 140 | 11.20 | 12.32 | 1.13 | 59.60 |

| Electricity from Renewable sources | % | 140 | 57.12 | 61.44 | 7.30 | 323.10 |

| Renewable energy share | % | 140 | 24.44 | 18.93 | 0.00 | 106.30 |

| Energy Efficiency Certificates (TEE) | Number per 1000 inhabitants | 140 | 613.77 | 667.64 | 12.59 | 3429.17 |

| Variables | SDG12 | ReCEI_comp | ReCEI Pillars |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic material consumption per capita | ✓ | ✓ | Decoupling |

| Urban wasteproduction | ✓ | ✓ | Waste production |

| Separate collection of municipal waste | ✓ | ✓ | Waste management |

| Circular material rate | ✓ | ✓ | Secondary Raw Material |

| ReCEI_comp—SDG12 | Pearson (r) | Spearman ρ | Kendall τ-b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coeffiecient | 0.7529 | 0.8932 | 0.7263 |

| p-value | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| N | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Dipendent Variable: ReCEI | M1 | M2 | M3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDP pro capite | −0.7039 (0.8642) | −0.9447 (0.7671) | |

| Industrial density | −6.4438 *** (1.6679) | −9.3755 *** (2.8296) | |

| EQI | 0.1842 (0.1123) | 0.0694 (0.1230) | |

| RIS | −2.3458 ** (1.0591) | −0.0768 (0.9561) | |

| Public investment in R&D | −0.2817 (0.2716) | 0.2014 (0.2565) | |

| Private investment in R&D | −0.2074 ** (0.0955) | 0.3836 * (0.1891) | |

| Industrial GVA | 0.0870 (0.5337) | ||

| Population density | −7.7414 * (4.3550) | ||

| _cons | 11.8615 (8.8439) | 1.8885 * (0.9548) | 53.3333 ** (25.1026) |

| N | 133 | 133 | 133 |

| pseudo R2 | |||

| Log Likelihood | −15.79 | −27.82 | −11.87 |

| Chi squared |

| Outcome Regional Circular Economic Index (ReCEI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Estimate | S.E. | T-Value | Partial R2 of the Treatment (R2yd.x) | Robustness (RV_q = 1) | Robustness of t-Value (RV_q = 1 a = 0.05) |

| Public Invstment in R&D | 18.418 | 2.9458 | 6.2522 | 0.2298 | 0.4171 | 0.3097 |

| Bound | R2dz.x | R2yz.dx | Coef. | S.E. | t(H0) | Lower CI | Upper CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.00× Institutional quality | 0.0066 | 0.0033 | 18.2604 | 2.9621 | 6.1647 | 12.4002 | 24.1206 |

| 2.00× Institutional quality | 0.0132 | 0.0066 | 18.1017 | 2.9671 | 6.1007 | 12.2316 | 23.9718 |

| 3.00× Institutional quality | 0.0199 | 0.0098 | 17.9419 | 2.9722 | 6.0366 | 12.0618 | 23.8221 |

| Regions | ReCED ReCEI | Distance (ReCEI-z3) | Regions | ReCED WasteProd | Distance (WasteProd-z3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trentino-Alto Adige | 0.003 | −0.11 | Sardinia | 0.007 | −2.23 |

| Veneto | 0.004 | −1.49 | Aosta Valley | 0.013 | −10.61 |

| Piedmont | 0.004 | −2.71 | Trentino-Alto Adige | 0.017 | −16.45 |

| Emilia-Romagna | 0.008 | −7.04 | Umbria | 0.026 | −28.20 |

| Lombardy | 0.008 | −8.19 | Piedmont | 0.027 | −28.61 |

| Friuli-Venezia Giulia | 0.014 | −15.71 | Basilicata | 0.031 | −34.22 |

| Basilicata | 0.016 | −17.96 | Veneto | 0.034 | −37.95 |

| Umbria | 0.023 | −27.92 | Emilia-Romagna | 0.034 | −38.17 |

| Molise | 0.031 | −38.38 | Friuli-Venezia Giulia | 0.036 | −40.37 |

| Aosta Valley | 0.031 | −38.69 | Lombardy | 0.044 | −51.56 |

| Regions | ReCED Decoup | Distance (Decoup-z3) | Regions | ReCED WasteManag | Distance (WasteManag-z3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marche | 0.002 | −0.16 | Liguria | 0.004 | −3.07 |

| Sardinia | 0.003 | −0.91 | Veneto | 0.008 | −8.34 |

| Friuli-Venezia Giulia | 0.003 | −1.16 | Marche | 0.009 | −8.89 |

| Emilia-Romagna | 0.003 | −2.06 | Lombardia | 0.012 | −13.14 |

| Abruzzo | 0.004 | −2.83 | Emilia-Romagna | 0.013 | −14.85 |

| Trentino-Alto Adige | 0.004 | −3.48 | Sardinia | 0.014 | −16.30 |

| Umbria | 0.009 | −11.14 | Umbria | 0.014 | −16.73 |

| Basilicata | 0.015 | −20.68 | Piedmont | 0.018 | −21.37 |

| Molise | 0.042 | −63.59 | Aosta Valley | 0.018 | −21.92 |

| Aosta Valley | 0.042 | −64.76 | Molise | 0.021 | −26.32 |

| Regions | ReCED WasteRecov | Distance (WasteRecov-z3) | Regions | ReCED SustInnov | Distance (SustInn-z3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trentino-Alto Adige | 0.003 | −0.63 | Umbria | 0.003 | −0.10 |

| Veneto | 0.005 | −3.56 | Sardinia | 0.003 | −0.25 |

| Emilia-Romagna | 0.010 | −11.02 | Marche | 0.006 | −2.83 |

| Piedmont | 0.011 | −12.58 | Aosta Valley | 0.007 | −3.99 |

| Liguria | 0.012 | −13.62 | Abruzzo | 0.008 | −4.76 |

| Basilicata | 0.013 | −15.55 | Apulia | 0.014 | −9.69 |

| Calabria | 0.016 | −20.12 | Calabria | 0.015 | −10.17 |

| Aosta Valley | 0.019 | −24.75 | Basilicata | 0.018 | −12.62 |

| Molise | 0.039 | −53.93 | Sicili | 0.029 | −21.25 |

| Umbria | 0.042 | −58.55 | Molise | 0.041 | −31.56 |

| Regions | ReCED EnvSust | Distance (EnvSust-z3) | Regions | ReCED EnvRes | Distance (EnvRes-z3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toscana | 0.004 | −1.95 | Piedmont | 0.002 | −0.29 |

| Umbria | 0.004 | −2.26 | Friuli-Venezia Giulia | 0.002 | −0.59 |

| Sardinia | 0.005 | −3.05 | Basilicata | 0.002 | −1.22 |

| Emilia-Romagna | 0.007 | −5.99 | Abruzzo | 0.003 | −1.91 |

| Veneto | 0.007 | −6.36 | Calabria | 0.003 | −2.51 |

| Basilicata | 0.008 | −7.04 | Trentino-Alto Adige | 0.004 | −3.39 |

| Friuli-Venezia Giulia | 0.009 | −8.44 | Umbria | 0.005 | −4.93 |

| Molise | 0.019 | −20.88 | Lombardy | 0.015 | −16.53 |

| Trentino-Alto Adige | 0.030 | −34.65 | Molise | 0.016 | −17.70 |

| Aosta Valley | 0.044 | −52.68 | Aosta Valley | 0.027 | −30.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arbolino, R.; De Simone, L.; Lopes, A. Distances from Efficiency: A Territorial Assessment of the Performance of the Circular Economy in Italy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11361. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411361

Arbolino R, De Simone L, Lopes A. Distances from Efficiency: A Territorial Assessment of the Performance of the Circular Economy in Italy. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11361. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411361

Chicago/Turabian StyleArbolino, Roberta, Luisa De Simone, and Antonio Lopes. 2025. "Distances from Efficiency: A Territorial Assessment of the Performance of the Circular Economy in Italy" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11361. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411361

APA StyleArbolino, R., De Simone, L., & Lopes, A. (2025). Distances from Efficiency: A Territorial Assessment of the Performance of the Circular Economy in Italy. Sustainability, 17(24), 11361. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411361