1. Introduction

Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance has become a central benchmark for measuring firm sustainability and long-term value creation [

1]. Over the past decade, profit-only evaluations by global investors and regulators have shifted towards more comprehensive approaches that incorporate social responsibility and sustainable practices into ESG evaluations of companies [

2,

3]. However, despite this shift, research on the role of firm-specific factors influencing ESG performance remains fragmented and has received limited empirical evidence, especially in emerging markets with varying enforcement and reporting practices distinct from those of Western nations [

4,

5]. China, being the world’s second-largest economy and a major player in global environmental pollution [

6] and the carbon neutrality initiative, is an optimal setting, as its ESG disclosure reporting system is growing rapidly and shows divergence among firms listed on Chinese stock exchanges [

7].

Although existing ESG research has provided some insights, it has some flaws and is not comprehensive enough [

4,

5]. Firstly, the available literature on ESG is mostly Western- or globally centered, with few studies on the determinants of ESG in the specific Chinese context [

8,

9]. Secondly, the available literature mainly focuses on the direct impact aspects. It neglects the importance of behavior- and strategy-related mechanisms, such as market structuring or the manager’s risk aversion within firms, in linking firm attributes to ESG outcomes [

10,

11]. Lovatte et al. [

12] highlight the mediating role of corporate social responsibility in the relationship between CO

2 emissions and the Environmental Kuznets Curve in Brazil and call for further empirical research. Thirdly, the effect of ownership concentration in the literature on ESG research is not clear from the perspective of theoretical aspects [

13,

14].

Based on stakeholder theory [

15], previous research has underscored that larger and transparent companies have been more susceptible to ESG pressures, as small firms lack corresponding motivations and resources [

16,

17]. Alternatively, some studies based on the resource-based view theory proposed that financially strong organizations have used their slack resources for sustainable projects and, as such, met two goals at once—profit maximization and establishment of legitimacy [

18,

19]. However, these arguments ignore the dynamic nature of firm characteristics’ effects on ESG performances [

20]. There is empirical evidence suggesting lagged effects of corporate governance and financial performance on improved ESG ratings [

21,

22], but these have rarely been examined in China’s A-share market [

23].

Moreover, there has been a lack of exploration on the behavioral and structural links between corporate features and ESG outcomes [

24,

25]. Financial metrics, such as return on equity (ROE), measure corporate profit but not necessarily risk preference or market intention as managerial behavior underlying ESG engagement [

26]. Additionally, ownership concentration can be supportive or limiting of sustainability efforts based on whether large shareholders aim for short-term or long-term legitimacy gains [

27]. To acknowledge such complex links, it is necessary to integrate agency theory [

28], which emphasizes the tensions between large and small shareholders, and legitimacy theory [

29], which treats ESG engagement as a behavior through which companies demonstrate congruence between corporate actions and societal expectations [

30,

31].

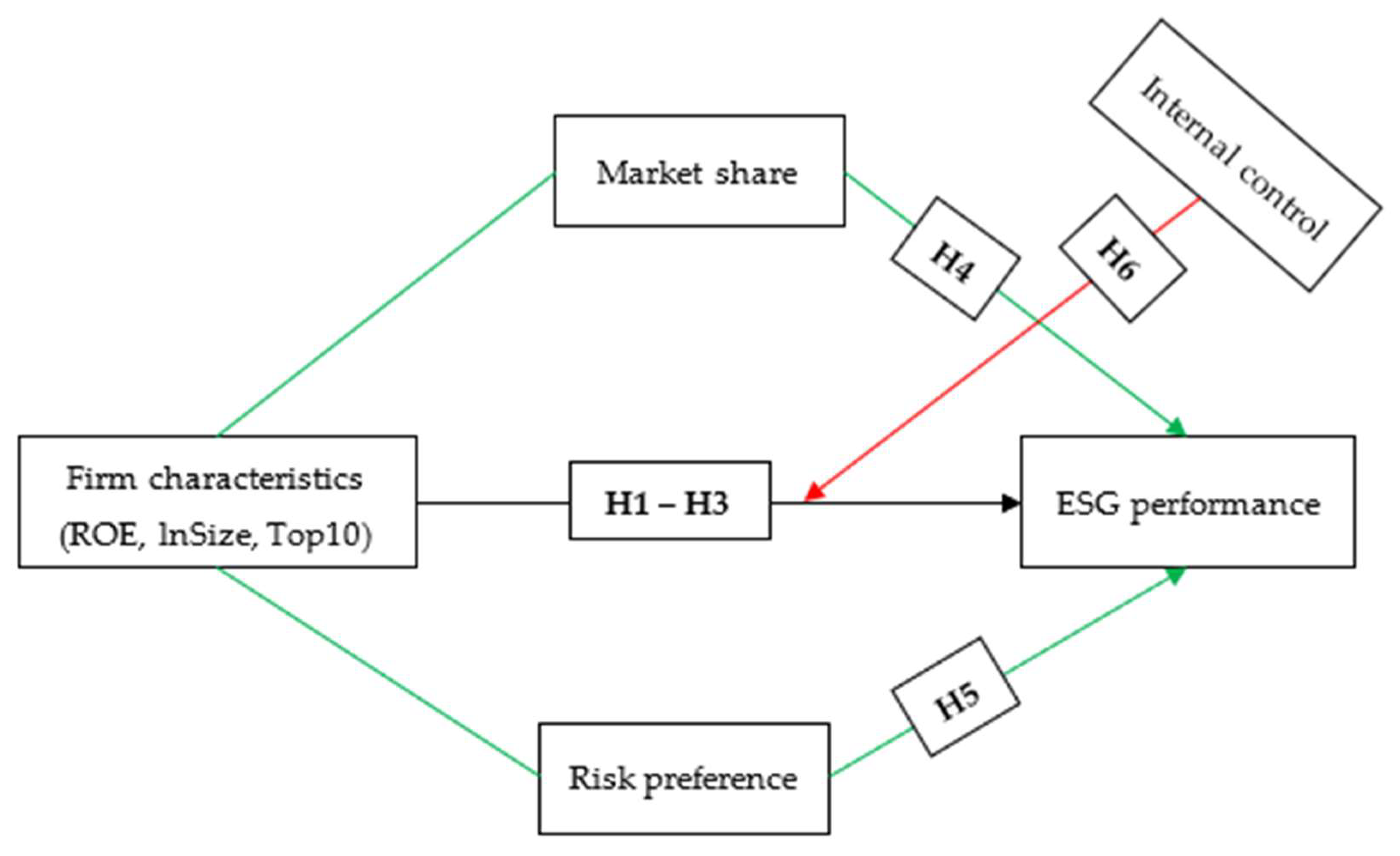

The proposed work differs by integrating the resource-based view [

32], the theory of legitimacy [

29], and agency theory [

28] in a structured manner, explicitly connecting each corporate attribute with a theory. Company size and profitability capture resource-based competitiveness, driving ESG investment, market share captures the pressures of legitimacy related to visibility, and ownership concentration and internal control capture governance structures related to agencies influencing managerial discretion. In this manner, our work enables the investigation of direct relationships and, importantly, the mediating and moderating roles of factors related to behavior (risk preference) and governance architecture (internal control) in influencing ESG in the Chinese setting, thereby integrating theories missing in earlier research.

Based on these research gaps, this research aims to answer the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1: Do company-based characteristics, such as ROE, size of firm, and its ownership concentration, impact ESG performance in the Chinese Listed companies?

RQ2: By what means or through what behavioral and strategic channels, specifically risk preference and market share, do these links operate?

RQ3: Do internal control and effective internal control systems act as a moderator of these effects?

By addressing the above RQs, this research adds to the literature in three ways. First, it enhances theoretical explanations on ESG performance issues because it employs all three theories of resource-based view [

33], agency [

28], and legitimacy theory [

29] together in explaining ESG performances, not only as they are directly influenced but through other variables like managerial actions and strategic orientation [

34,

35]. Second, it contributes methodologically by using panel data on Chinese A-share companies, testing contemporaneous and lagged hypotheses, and emphasizing the diffusion of ESG effects over time [

36,

37]. Lastly, this work also has practical contributions for policymakers and managers who would like to create sustainable value and link profit and governance structures through emerging markets.

The following research is organized as follows:

Section 2 covers the theoretical foundation and develops hypotheses, and

Section 3 describes the empirical methods, including the variables. The section covers results and tests of robustness, while covering a discussion of findings, implications, and future directions.

5. Discussion

5.1. Result Discussions

In this research, the impact of corporate profitability, size, and ownership structure on ESG performance was tested for listed companies in China. Based on the RBV, legitimacy, and agency theories, the hypotheses posit that market share and risk preference serve as mediating mechanisms and that the impact of firms’ characteristics on ESG is tempered by corporate internal control. Our hypotheses were supported with important differences for the specific context of the Chinese capital market.

Regarding the H1, the study observed a positive impact of ROE on ESG performance, consistent with the RBV assumption that financially stronger companies have the slack resources needed to invest in the sustainability efforts [

1,

112]. This is consistent with the notion advanced by other researchers, who argue that financial success enables firms to exhibit green innovation, thereby achieving legitimacy [

113,

114]. This finding validates the legitimacy theory assumption, given that profitable companies are often involved in ESG activities to maintain their societal acceptance and improve firm responsibility images.

Concerning H2, the size of the firm is observed to improve ESG outcomes because large firms have greater visibility in the public eye and are therefore more likely to engage in sustainability reporting practices, supporting the legitimacy theory [

57,

67]. This indicates that firms engage in ESG practices for self-interest rather than for virtuous motives to be morally good or good humanitarians [

115]. Hence, the result is in line with legitimacy theory by showing how reputable companies act to maintain their social image and stakeholder support.

Regarding H3, the study observed a significantly negative impact of ownership concentration on ESG performance, consistent with the agency theory assumption [

28] that large stockholders often place greater emphasis on financially oriented short-term objectives than on long-run stakeholder interests [

34,

60]. The negative impact is stable under various specifications, including alternative ownership measures (HHI), suggesting that governance frictions continue to shape sustainability behavior in the Chinese context.

Furthermore, the mediation results supported H4 and H5, indicating that market share and managerial risk preferences play the role of behavioral channels between firm attributes and ESG performance outcomes. More profitable and larger firms tend to enjoy stronger market power, which may make them more vulnerable to stakeholder monitoring and pressures for legitimacy [

64]. There is clear support for the notion of “competitive legitimacy,” according to which firms maintain their leading positions in the marketplace by behaving in socially virtuous ways [

30]. While smaller firms may find ways to distinguish themselves on ESG performance at specific instances, the overall environment for the Chinese A-share market is one that focuses on larger and more visible firms. Therefore, empirical findings of a positive connection between market share and ESG performance align with institutional expectations. Most importantly, in line with the study methodology, these mediation effects are recommended to be interpreted in a suggestive, rather than a definitive, causal manner. Further, consistent with the well-known limitations of mediation tests in fixed-effects panel analysis, the finding above is considered tentative evidence.

Where managerial risk preference is concerned, the mediation effect between firm characteristics and ESG performance is affirmatively supported. The proxy for this variable is intensity for fixed assets and R&D investment, which captures a strategic orientation to a longer-run investment compared to behavioral risk preferences. The study result that risk-oriented organizations invest more in ESG efforts is consistent with growing literature connecting long-run strategic horizons with firm sustainability-driven engagement [

36,

116]. Notably, this outcome does not contradict agency theory. However, it suggests that risk-preference leaders could support long-run sustainability efforts, whereas strong governance within a firm protects against opportunistic short-termism. These distinguish behavioral paths that converge to support the ESG outcome.

Regarding H6, the moderating outcomes indicate that internal control plays a critical role in shaping the relationships among profitability, size, and ESG performance [

87]. For companies with stronger internal controls, the positive impact of profitability ratios and size on ESG disclosures is more substantial. This result is more consistent with agency theory prescriptions for governance that focus on monitoring and supporting an environment- and stakeholder-focused management decision-making process [

107,

117]. The result supports the role of good governance structures as institutions that turn ESG commitment into performance [

118]. Furthermore, good governance also provides evidence and assurance related to the ESG efforts, ensuring transparency and legitimacy [

119]. Additionally, an effective control system offers insight into the critical threshold levels for governance credibility, with distinct between-company variations from the more general internal control-index trends. However, the strength and direction of such interaction terms could be driven by overall institutional reporting trends; therefore, careful attention is recommended when interpreting.

The study reveals consistent patterns across ESG sub-dimensions (environmental, social, governance). Analysis shows that the effect of firm characteristics is similar across environment, social, and governance factors. This is consistent with the integrated structure of WIND’s ESG rating system and emphasizes that resource capacity and pressures for legitimacy and ownership structures play relatively equal roles across the separate ESG factors. Further research suggested examining ESG factors across specific sectors to determine whether they tend to be more sensitive to resource factors and governance structures.

Finally, lagged models place strong emphasis on the significance of time. Although profits and size lead ESG performance in the following time period, the short time horizon (2021 to 2023) may represent a combination of actual adjustment behaviors and ESG reporting delays. ESG rating reporting is carried out on an annual basis, with known time gaps for observations on ESG ratings within the context of the Chinese economy; therefore, part of the time effect is driven by actual measurements and behaviors. This does not undermine the directionality of the results but introduces caution in interpreting dynamic patterns.

5.2. Implications

5.2.1. Theoretical Implications

First, while the literature has extensively examined the direct impact of corporate features such as size, ownership structure, and profitability on ESG performance [

50,

57,

62], relatively few works explain the underlying channels through which these corporate features affect ESG performance [

83]. This research extends and complements the ESG literature, which broadly focuses on ownership types and board traits [

80,

102], by introducing managerial risk preferences and market share as behavioral channels and by emphasizing the mediating mechanisms linking organizational resources, managerial decision-making, and stakeholder visibility to ESG performance.

Second, this study also extends the literature by developing a framework that integrates the RBV, agency theory, and legitimacy theory. Contrary to much prior research that uses multiple theories simultaneously and separately [

31,

40,

120]. This framework spells out how internal resources (RBV) [

33], control dynamics and ownership (agency theory) [

28], and external legitimacy (legitimacy theory) [

67] combine to form organization ESG performance. This theoretical integration of the study clarifies the theoretical pathways underlying observed ESG heterogeneity in China and shows how distinct theoretical logics converge through behavioral channels.

Third, this study is also significant to the growing literature on the behavioral underpinnings of firm sustainability investing, as it shows that managerial risk-taking behavior partially mediates the relationship between corporate characteristics and ESG performance. The research suggests that risk-taking behavior can serve as a potential underpinning for investing in firm sustainability, and that this can be supported by strong corporate internal governance. Further, this extends the current research by reflecting how managerial behavioral patterns and governance constraints interact, offering a more nuanced understanding of sustainability decision-making in emerging markets [

34,

121].

Third, the study draws attention to the role of the internal control system itself, emphasizing its significance in the sustainability context, where it plays a crucial role in enabling the sustainability process [

86,

118]. The study clearly indicates that internal control serves as a moderator between the firm’s attributes and ESG outcomes [

87,

118]. The concept of distinguishable governance quality (internal control) and categorical governance certification (effective internal control) offers ESG studies a more complex framework for understanding governance processes.

5.2.2. Practical Implications

The study results have important implications for investors, managers, and policymakers. First, the study’s implications for corporate managers highlight the importance of profitability and size, used not only for financial gain but also for sustainability advantages. Managers are advised to adopt a risk-seeking stance, focusing on financial resources directed to innovation linked to ESG rather than other financial investments.

Second, the implication for board members or controlling shareholders is the importance of maintaining control while balancing accountability, as overly concentrated ownership hinders ESG efforts. Diversifying ownership structures is one way to align stakeholders’ interests with sustainability considerations.

Third, regarding policy regulators, improvements in the standard of disclosure of internal controls, coupled with tighter ESG reporting guidelines, are beneficial for firms in terms of transparency and performance. Regulators promote the reporting of “effective internal control” to encourage firms to integrate ESG considerations into their operations.

Lastly, from the investor perspective, the implication is that ownership concentration remains an essential risk indicator in assessing ESG performance. Organizations with dispersed ownership and a strong, effective governance structure are more likely to deliver credible, stable ESG outcomes. In addition, managerial investment and market share behavior also serve as essential indicators of organizations’ sustainability trajectories, providing additional dimensions for screening ESG and portfolio formation.

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Although the work has many strengths, there are also some limitations for future studies to explore. Firstly, although the use of secondary data from panels contributes to greater objectivity, there may be unseen managerial or cultural variables shaping ESG practices. In addition, the sample period (2021–2023) is relatively short, limiting the extent to which true adjustment can be measured. A future study is suggested to use archival research methods in partnership with survey or interview methods to more thoroughly tap into managerial cognition. Additionally, a longer time window assists in distinguishing reporting-related lags from strategic ESG transitions.

Secondly, since this work is based on Chinese A-share firms, it makes it difficult to generalize the results to other institutions, possibly creating room for future studies in other Asian or Belt and Road countries. Thirdly, although the model used the variables’ lagged values and instruments, the problem of endogeneity cannot be completely discounted. The study is suggested to be expanded in the future by employing dynamic panels, specifically the Generalized Method of Moments.

Fourthly, the mediation model uses step-wise regression, an approach that is less stringent than the bootstrapped panel model or SEM. Since the bootstrapped panel model and the SEM could not be conducted in this study, the indirect effects and confidence intervals could not be estimated. The results obtained from the model regarding the mediation effect may therefore be considered preliminary.

Fifth, although this study follows a traditional methodological approach to managerial risk preference by quantifying risk preference as the proportion of investments in R&D and fixed assets relative to overall assets, this proxy aggregates investment categories that differ in risk properties. Future studies are suggested to consider the use of surveys and other indicators, such as earnings volatility and innovation intensity. Not only is this true when outliers are dealt with via winsorization and manual checks, but there is also volatility inherent in emerging market data owing to the denominator effect. Future research is suggested to explore the application of strong regression methods and Bayesian estimators.

Finally, this research focuses on the characteristics and channels at the corporate and behavioral levels. Future research is suggested to add board network properties and outside pressures, as well as executive characteristics, to obtain a more complete picture on ESG diversity for emerging markets such as China. Also suggested examining industry-specific ESG factors, as the environmental and social forces acting on high-emission industries differ significantly from those on low-emission sectors, including finance and technology.

6. Conclusions

The current study examined the relationships between the firms’ characteristics (e.g., profitability, size, and ownership concentration) and their ESG performance. Additionally, specific emphasis is placed on the mediating impacts of market share and risk preference, as well as the moderative roles played by the internal control system, utilizing the three theories, namely the agency, legitimacy, and resource-based. The result indicates that profitable firms, large firms, and those with strong risk preferences perform well on ESG, but ownership concentration hinders sustainability engagement.

Market share and managerial risk preference are the behavioral channels transmitting firm attributes to ESG performance, and strong internal controls are also beneficial. The findings support the proposition that financial resources, strategic behaviors, and ESG performance are all crucial in deciding firm sustainability. This work contributes to integrated theoretical and practical insights, prompting managers to connect the profitability of the firm with long-term ESG strategies, while also encouraging regulators to improve the framework of internal control/ESG reporting.