Aquaculture Industry Composition, Distribution, and Development in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

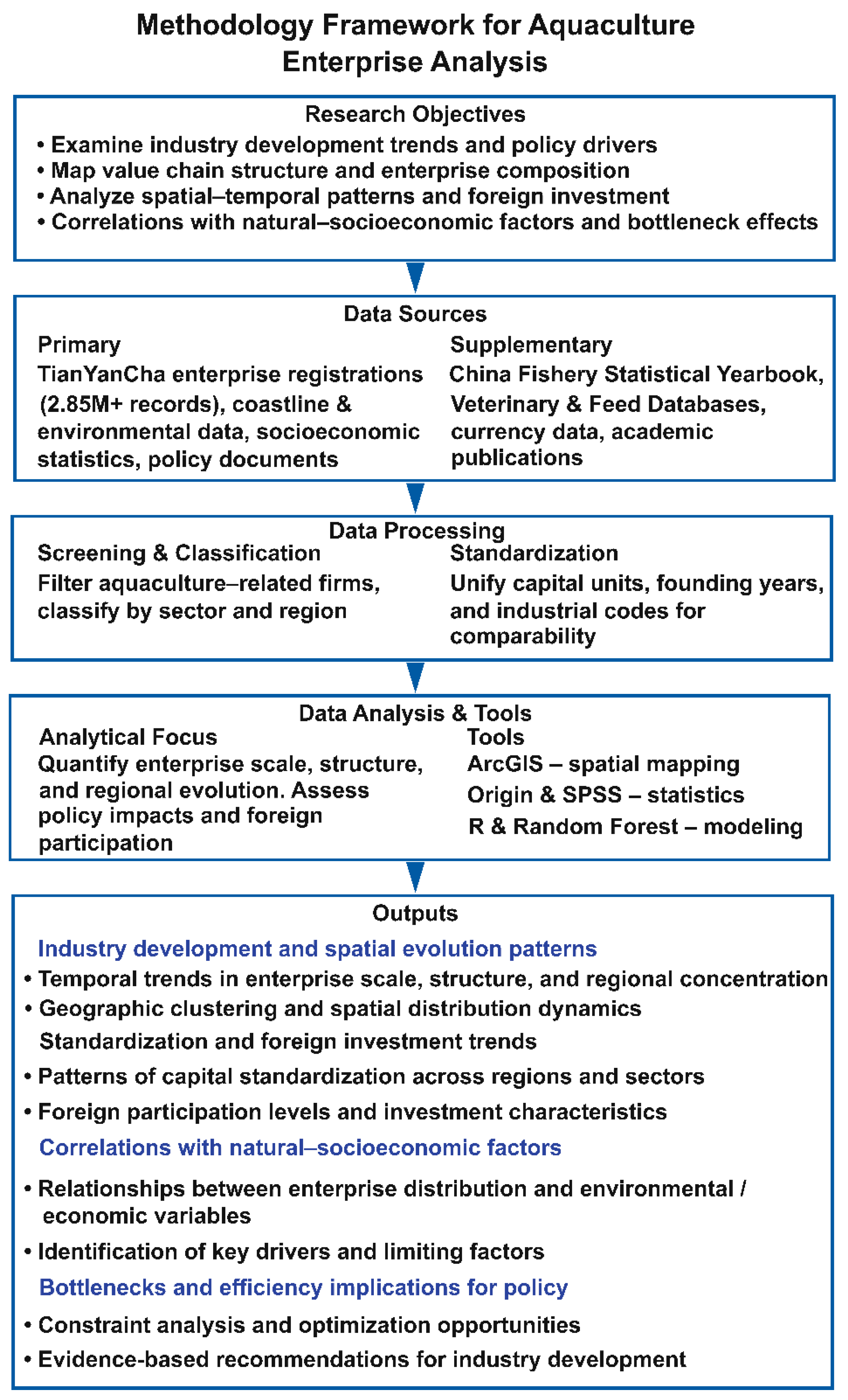

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Data Preprocessing

2.2.1. Data Screening and Classification

2.2.2. Data Standardization

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Temporal and Spatial Analysis

2.3.2. Financial and Structural Analysis

2.3.3. Bottleneck and Foreign Investment Analysis

3. Results

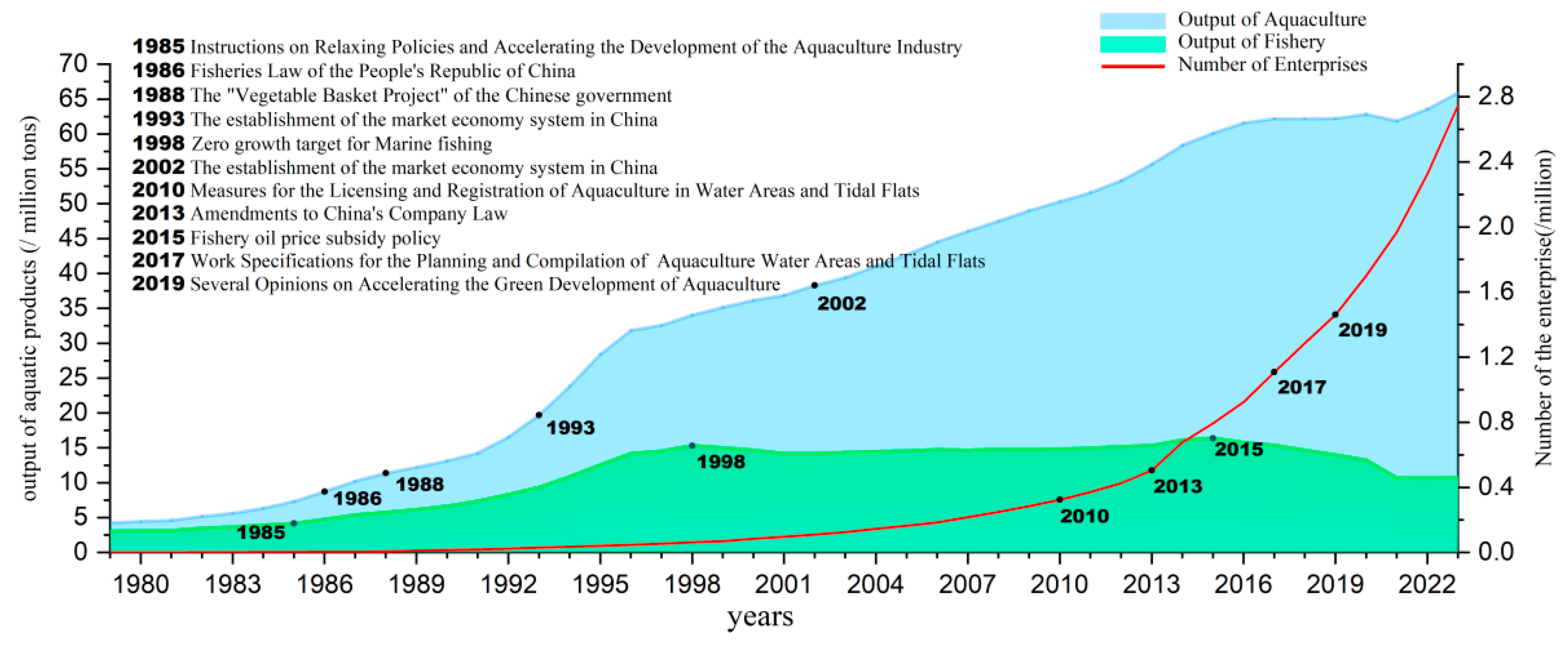

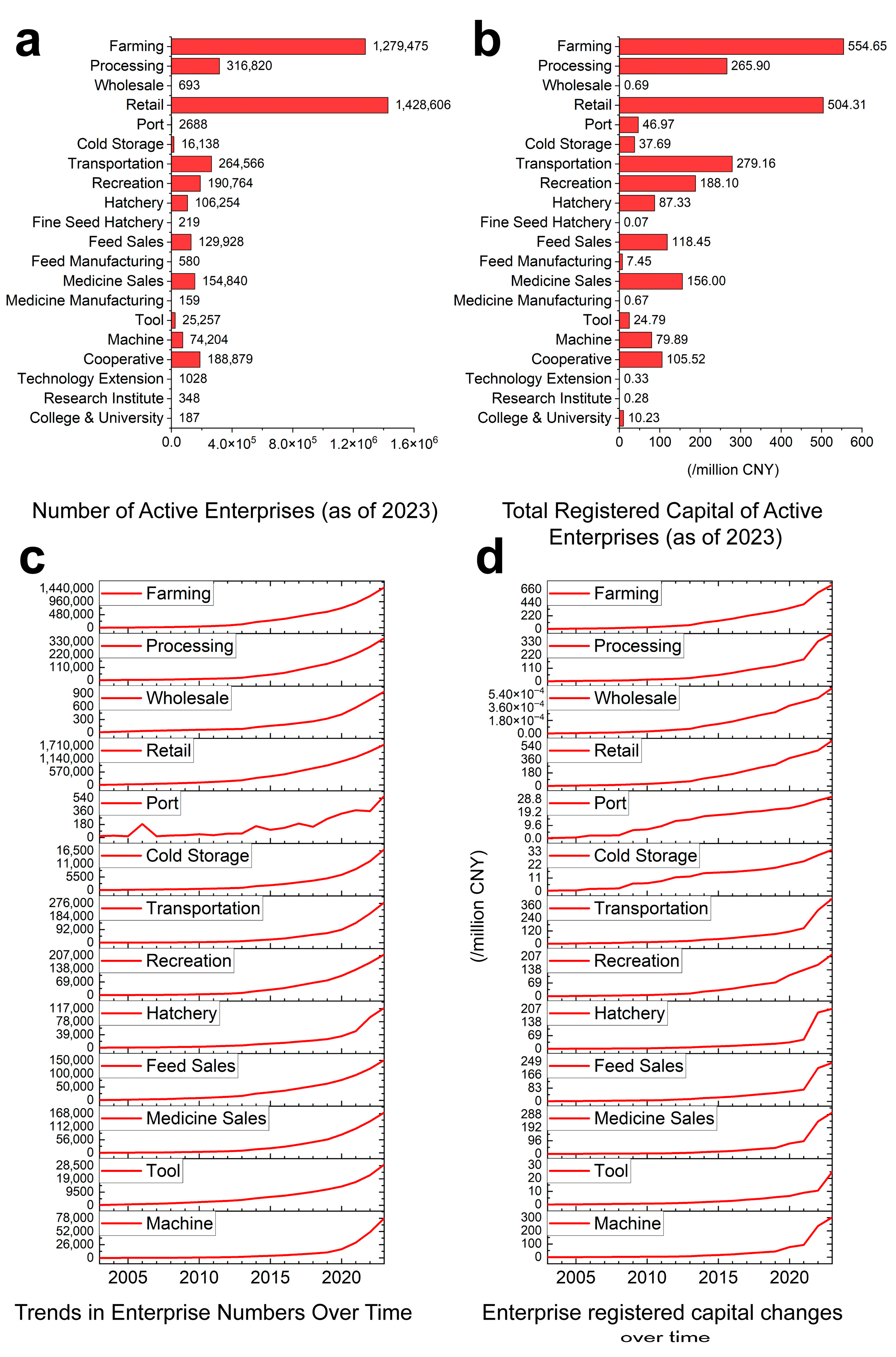

3.1. Policy, Number of Enterprises, Registered Capital, and Changes over Time

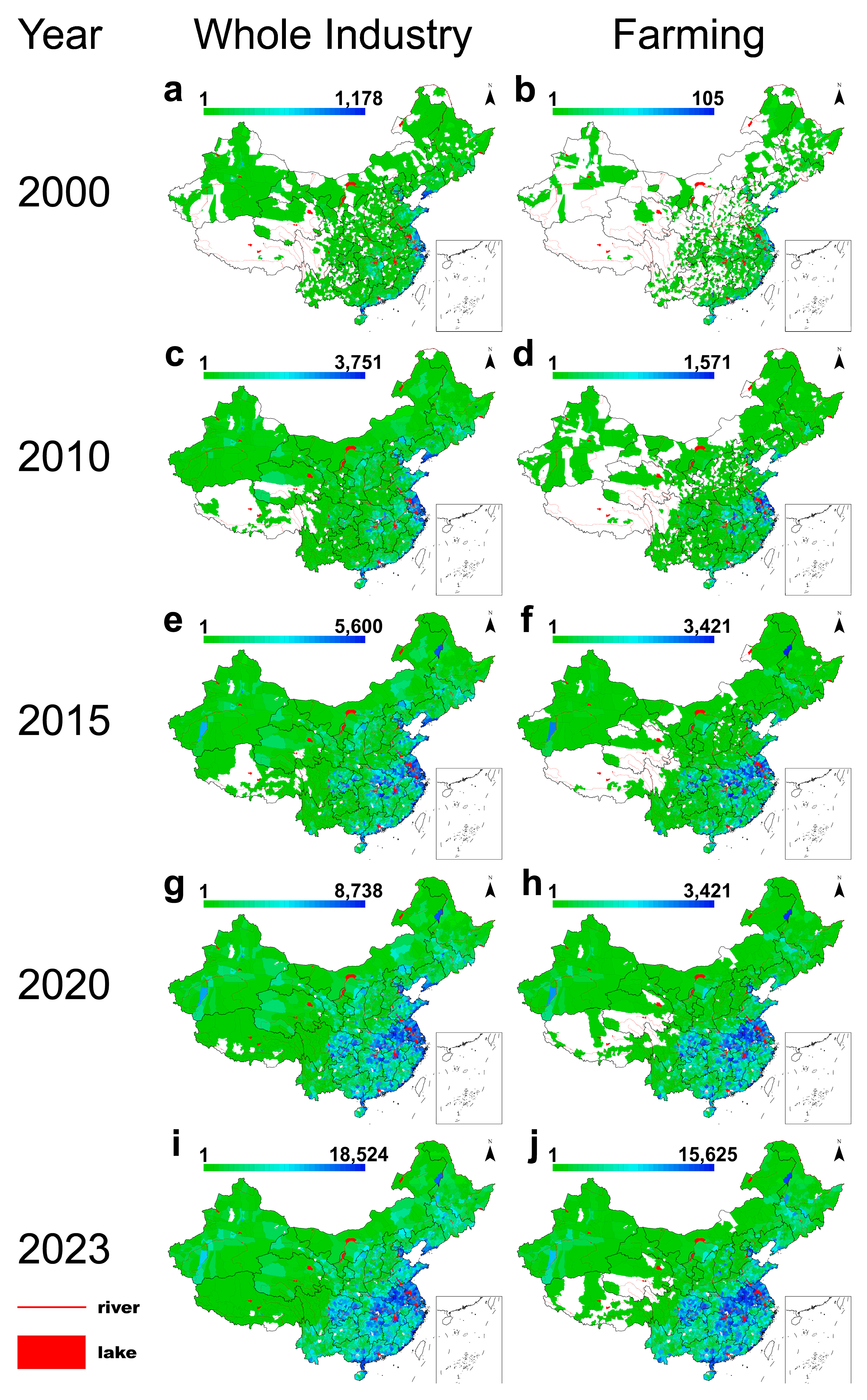

3.2. Geographic Distribution and the Temporal and Spatial Changes

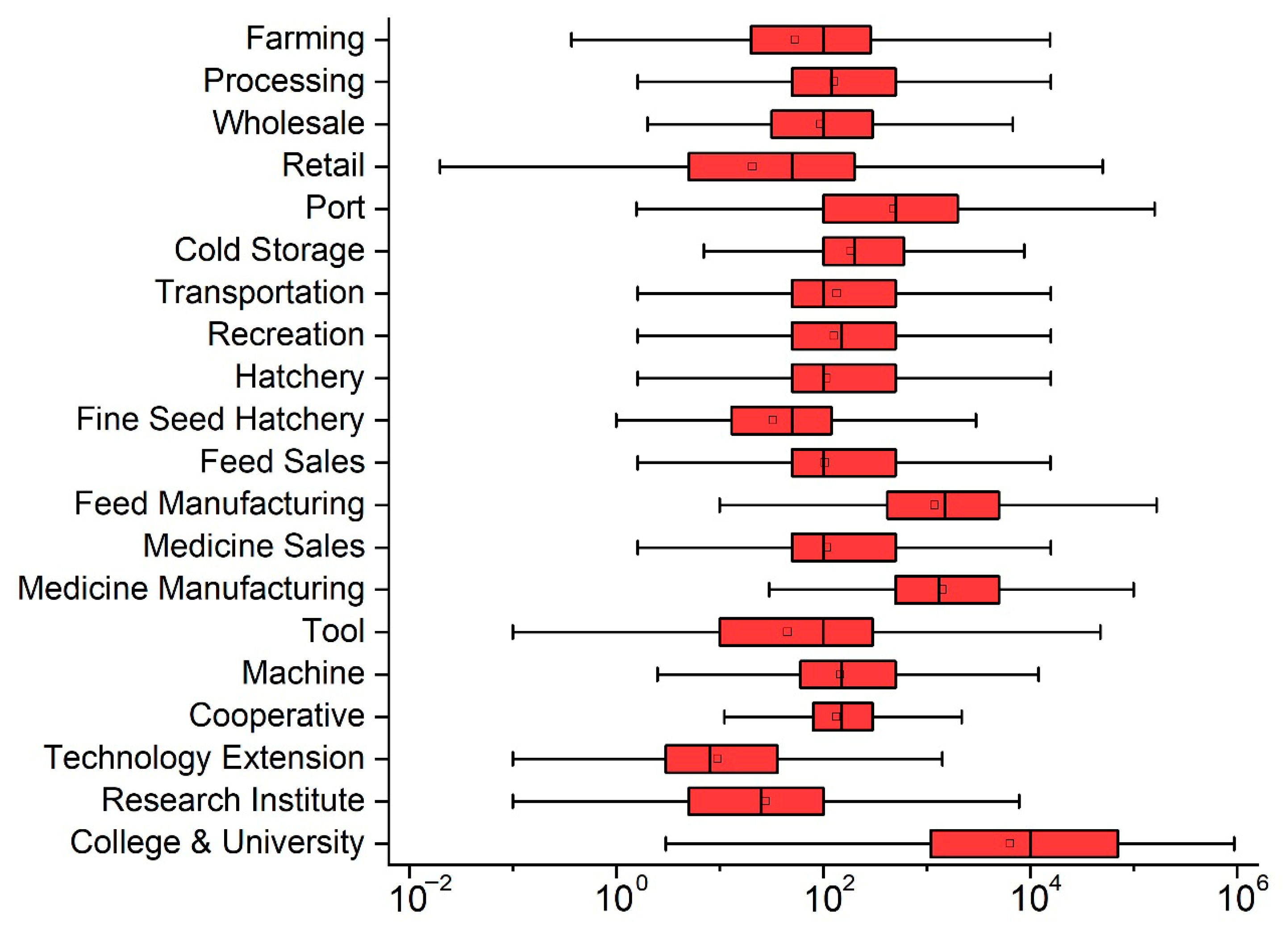

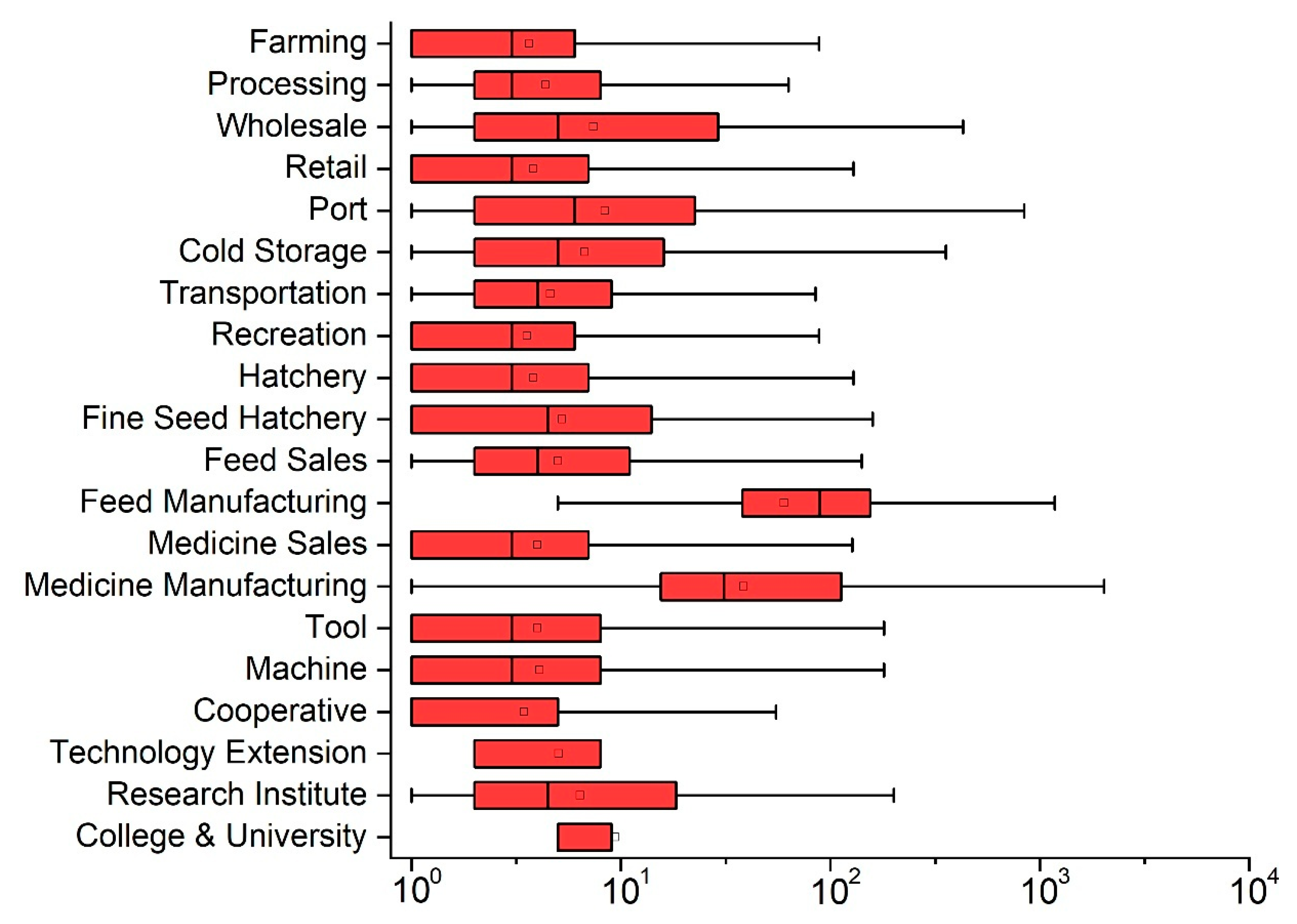

3.3. Sectoral Variations in Operational Performance and Formalization Levels

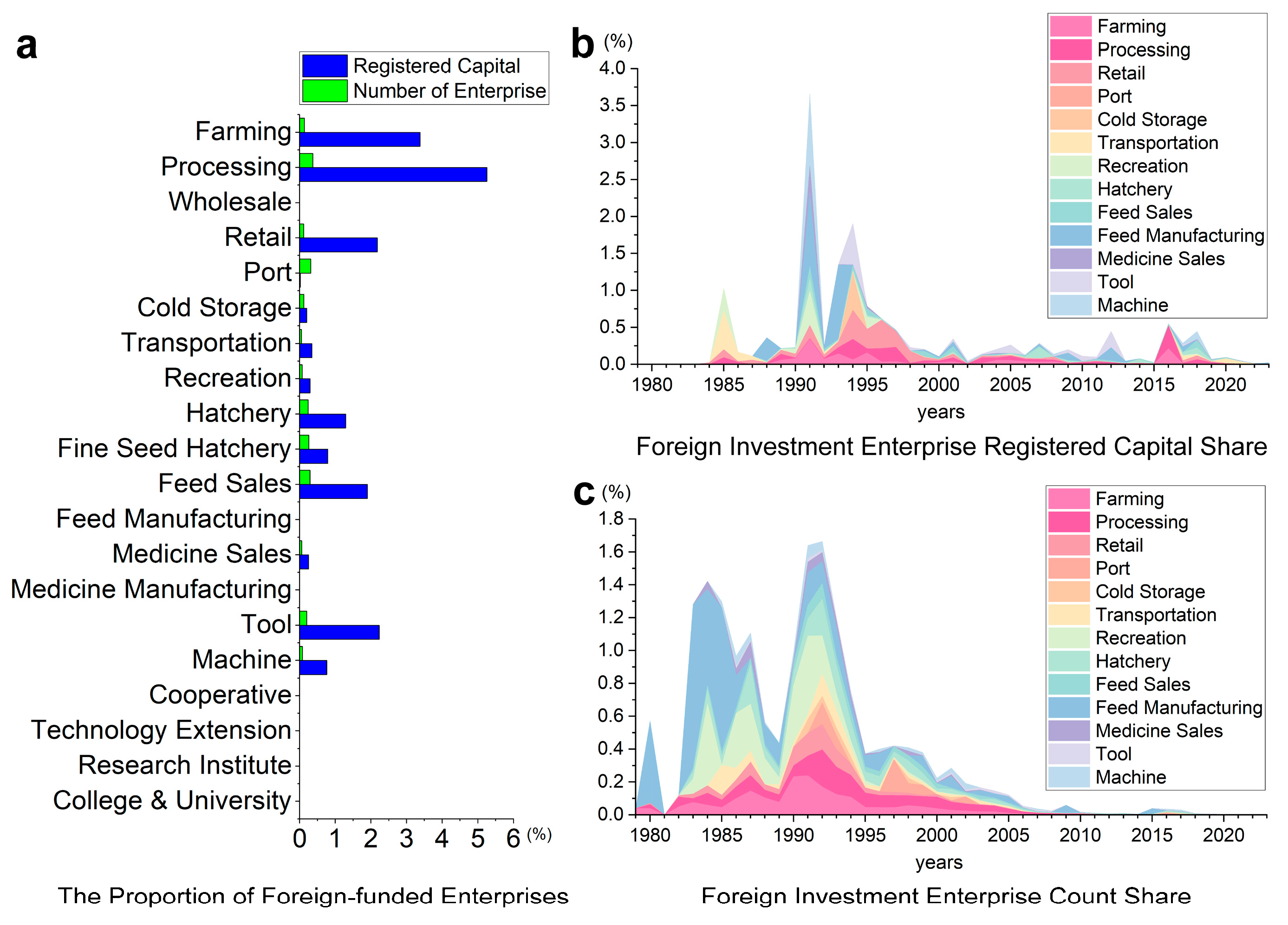

3.4. Foreign Investment

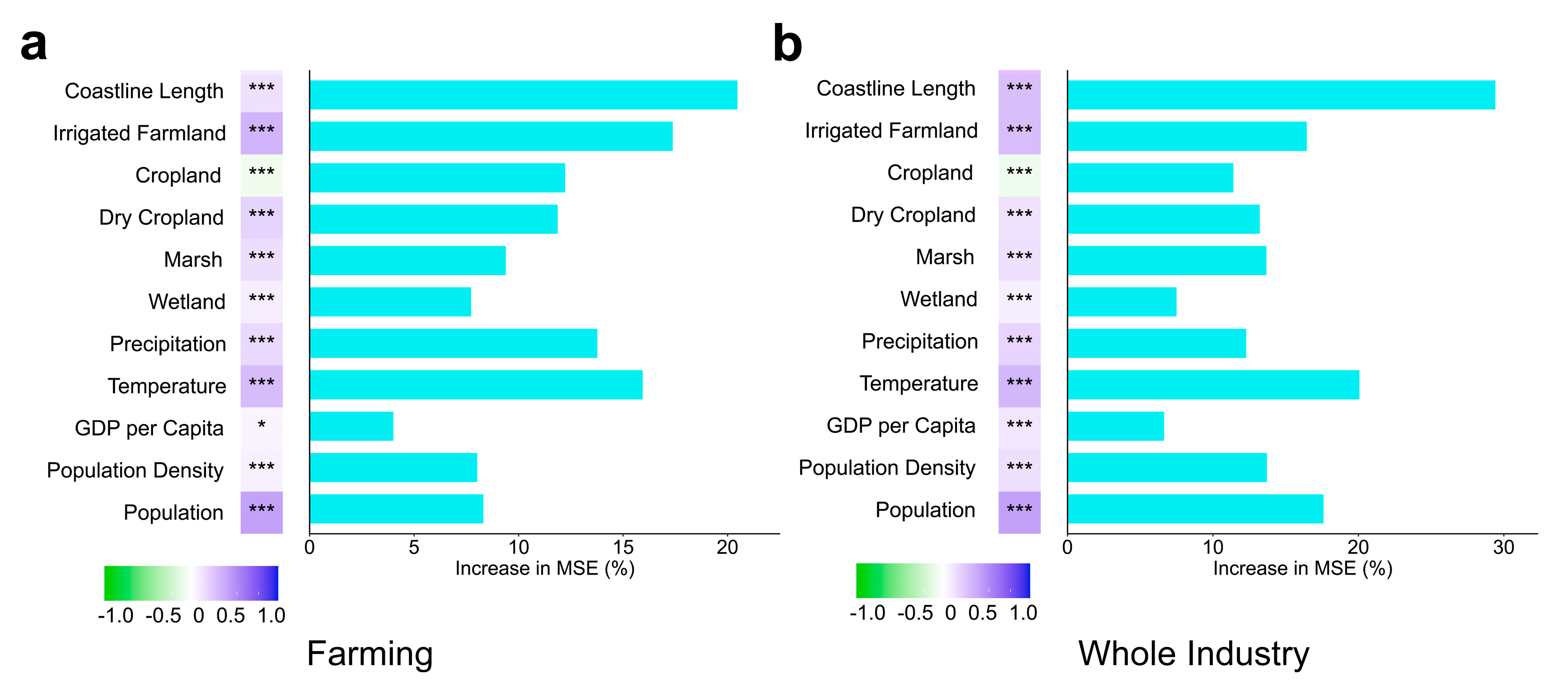

3.5. Structural Interdependencies and Correlation with Natural Endowments and Socioeconomic Factors

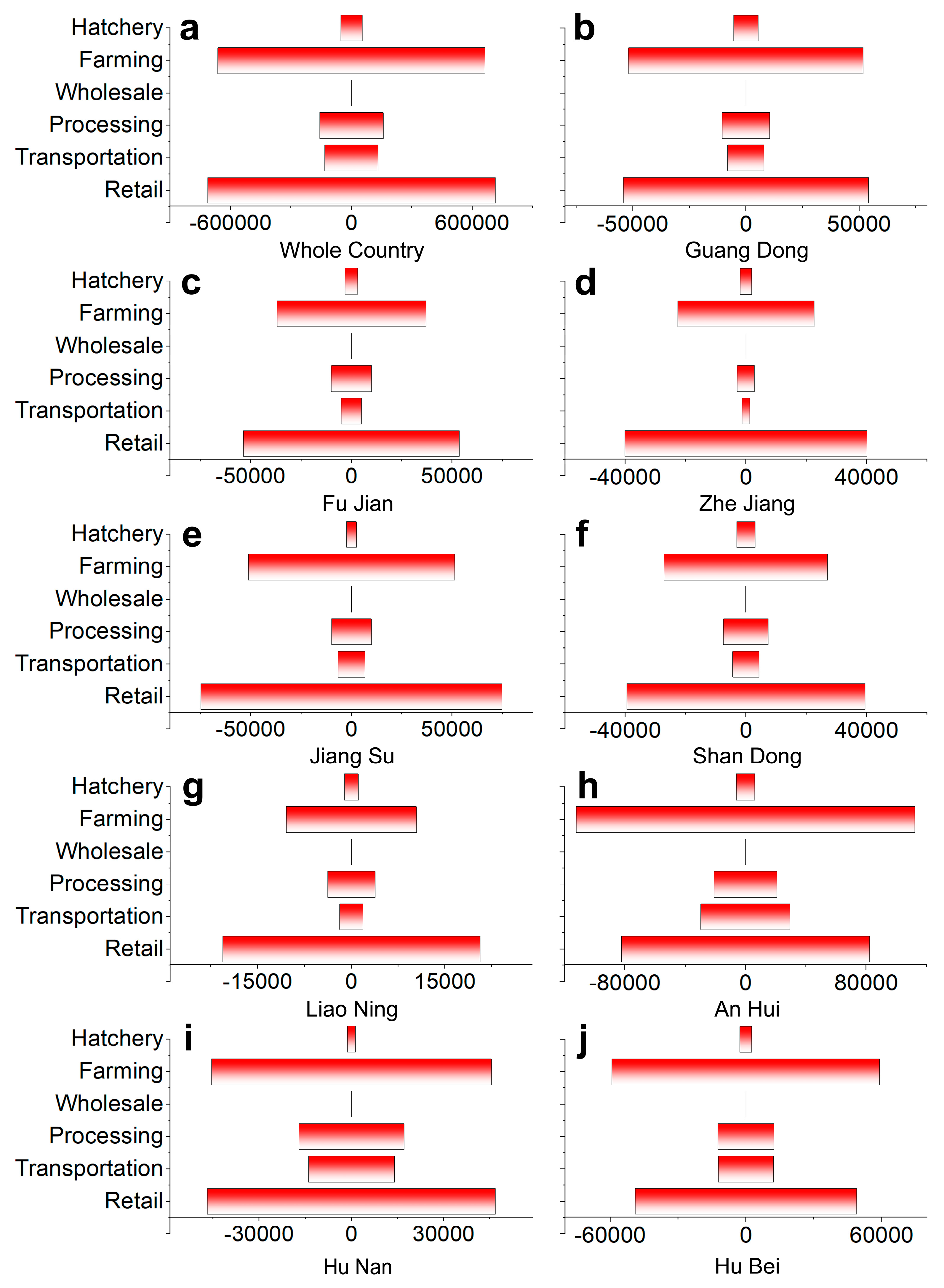

3.6. Structural Bottleneck

4. Discussion

4.1. Policy

4.2. Number of Enterprises

4.3. Structural Interdependencies

4.4. Geographic Distribution and Correlation with Natural Endowments and Socioeconomic Factors

4.5. Contribution of Foreign Investment

4.6. Standardization Level

4.7. Bottleneck Effect

4.8. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iannotti, L.L.; Blackmore, I.; Cohn, R.; Chen, F.; Gyimah, E.A.; Chapnick, M.; Humphries, A. Aquatic Animal Foods for Nutrition Security and Child Health. Food Nutr. Bull. 2022, 43, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, C.D.; Koehn, J.Z.; Shepon, A.; Passarelli, S.; Free, C.M.; Viana, D.F.; Matthey, H.; Eurich, J.G.; Gephart, J.A.; Fluet-Chouinard, E.; et al. Aquatic foods to nourish nations. Nature 2021, 598, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naylor, R.L.; Hardy, R.W.; Buschmann, A.H.; Bush, S.R.; Cao, L.; Klinger, D.H.; Little, D.C.; Lubchenco, J.; Shumway, S.E.; Troell, M. A 20-year retrospective review of global aquaculture. Nature 2021, 591, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024. Blue Transformation in Actio; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024; ISBN 978-92-5-138763-4. [Google Scholar]

- MARA. National Fisheries Economic Statistics Bulletin 2024; MARA: Beijing, China, 2025. Available online: https://yyj.moa.gov.cn/gzdt/202507/t20250707_6475475.htm (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Newton, R.; Zhang, W.; Xian, Z.; Mcadam, B. Intensification, regulation and diversification: The changing face of inland aquaculture in China. Ambio 2021, 50, 1739–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, C.; McNevin, A. Aquaculture, Resource Use, and the Environment; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pillay, T.V.R. Aquaculture and the Environment; John Wiley& Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Salin, K.R.; Arome Ataguba, G. Aquaculture and the Environment: Towards Sustainability. In Sustainable Aquaculture; Hai, F.I., Visvanathan, C., Boopathy, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–62. ISBN 978-3-319-73257-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlock, T.M.; Asche, F.; Anderson, J.L.; Eggert, H.; Anderson, T.M.; Che, B.; Chávez, C.A.; Chu, J.; Chukwuone, N.; Dey, M.M.; et al. Environmental, economic, and social sustainability in aquaculture: The aquaculture performance indicators. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, Z. Spatial–Temporal Mapping and Landscape Influence of Aquaculture Ponds in the Yangtze River Economic Belt from 1985 to 2020. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Yin, Y.; Wu, G. Mapping Aquaculture Areas with Multi-Source Spectral and Texture Features: A Case Study in the Pearl River Basin (Guangdong), China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, D.; Liu, S.; Ji, H. Mapping national-scale aquaculture ponds based on the Google Earth Engine in the Chinese coastal zone. Aquaculture 2020, 520, 734666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, F.; Liu, B.; Cai, P. Satellite-based monitoring and statistics for raft and cage aquaculture in China’s offshore waters. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2020, 91, 102118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.; Yang, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, B. Spatial Distribution and Differentiation Analysis of Coastal Aquaculture in China Based on Remote Sensing Monitoring. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Chen, X.-J. Development of Chinese fishery industry in 40 years of reform and opening up and production forecast in the 14th five-year plan. Reprod. Breed. 2021, 30, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, F. A Significant Transformation in the History of Fisheries Development in New China; Chinese Fisheries Economics: China. 2008, 27–34.

- Wang, P.; Ji, J.; Zhang, Y. Aquaculture extension system in China: Development, challenges, and prospects. Aquacure. Rep. 2020, 17, 100339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Gao, S. Current status of industrialized aquaculture in China: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 32278–32287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NBSO. An Overview of China’s Aquaculture; NBSO: Dalian, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta, B.O.; Gupta, M.V. The genetic improvement of farmed tilapias project: Impact and lessons learned. In Success Stories in Asian Aquaculture; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 149–171. [Google Scholar]

- Hambrey, J.; Edwards, P.; Belton, B. An ecosystem approach to freshwater aquaculture: A global review. In Building an Ecosystem Approach to Aquaculture; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2007; p. 231. ISBN 9789251060759. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. Selling China: Foreign Direct Investment During the Reform Era; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Huang, J. China’s Accession to the WTO and Its Implications for the Fishery and Aquaculture Sector. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2005, 9, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Fu, L.; Fu, Y.; Li, B.; Jiao, B. Aquaculture Industry in China: Current State, Challenges, and Outlook. Rev. Fish. Sci. 2011, 19, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N. Chinese Aquaculture: Its Contribution to Rural Development and the Economy. In Aquaculture in China; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 55–69. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Ma, X. China’s aquaculture development trends since 2000 and future directions. J. Shanghai Ocean Univ. 2020, 29, 661–674. [Google Scholar]

- Su, M.; Cheng, K.; Kong, H. Spatial and Temporal Differentiation of the Coordination and Interaction among the Three Fishery Industries in China from the Value Chain Perspective. Fishes 2023, 8, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsson, E.; Asche, F.; Nielsen, M. Revenue Distribution Through The Seafood Value Chain. FAO Fish. Circ. 2006, 1019, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, P.; Mizgier, K.J.; Jüttner, M.P.; Wagner, S.M. Bottleneck identification in supply chain networks. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2012, 2012, 695878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Sun, C. Asymmetric Price Transmission and Market Power: A Case of the Aquaculture Product Market in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, P.F.M. Extracted and farmed shrimp fisheries in Brazil: Economic, environmental and social consequences of exploitation. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2008, 10, 639–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Tian, B.; Li, X.; Liu, D.; Sengupta, D.; Wang, Y.; Peng, Y. Tracking changes in aquaculture ponds on the China coast using 30 years of Landsat images. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 102, 102383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Pu, R.; Cao, L.; Zhang, H.; Ai, S.; Yang, Y. Mapping Coastal Aquaculture Ponds of China Using Sentinel SAR Images in 2020 and Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Huang, J.; Ling, F.; Qiu, J.; Liu, Z. Dynamic Mapping of Inland Freshwater Aquaculture Areas in Jianghan Plain, China. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 4349–4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yang, X.; Huang, C.; Su, F.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Global mapping of the landside clustering of aquaculture ponds from dense time-series 10 m Sentinel-2 images on Google Earth Engine. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 115, 103100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Mu, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhuo, H.; Qiu, G.; Chen, J.; Lei, M.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Assessing 30-Year Land Use and Land Cover Change and the Driving Forces in Qianjiang, China, Using Multitemporal Remote Sensing Images. Water 2023, 15, 3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFeely, S.; Delaney, J.; O’Donoghue, F. Using Business Registers to Conduct a Regional Analysis of Enterprise Demography and Employment in the Tourism Industries: Learning from the Irish Experience. Tour. Econ. 2013, 19, 1293–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Gui, Z.; Wu, H.; Gong, J.; Wang, Y.; Tian, S.; Zhang, J. Big enterprise registration data imputation: Supporting spatiotemporal analysis of industries in China. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2018, 70, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Liu, X.; Sheng, H.; Yuan, Z. MAPS: A new model using data fusion to enhance the accuracy of high-resolution mapping for livestock production systems. One Earth 2023, 6, 1190–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Peng, Y.; Qin, B. The Typology of Urban Polycentricity: A Comparative Study of Firm Distribution in 35 Chinese Cities. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawagreh, K.; Gaber, M.M.; Elyan, E. Random forests: From early developments to recent advancements. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 2014, 2, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MARA 2024 China Fisheries Statistical Yearbook; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2024.

- Naylor, R.; Fang, S.; Fanzo, J. A global view of aquaculture policy. Food Policy 2023, 116, 102422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crona, B.; Wassénius, E.; Troell, M.; Barclay, K.; Mallory, T.; Fabinyi, M.; Zhang, W.; Lam, V.W.Y.; Cao, L.; Henriksson, P.J.G.; et al. China at a Crossroads: An Analysis of China’s Changing Seafood Production and Consumption. One Earth 2020, 3, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.L.; Collins, E.J.T. The coordinating role of local government in agricultural development with special reference to small-scale household pond aquaculture in China 1979–2011. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2013, 17, 398–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L. Implement the “vegetable basket project” to solve the problem of urban supplementary food supply. Chin. Rural Econ. 1988, 9–10+36. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, L. Reforms to China’s Company Registration Law; Washington, DC, USA, 2014. Available online: https://www.wilmerhale.com/en/insights/client-alerts/reforms-to-chinas-company-registration-law (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- MOA. A symposium on the implementation and enforcement of the “Regulations on Issuance and Registration of Aquaculture in Water Bodies and Coastal Areas” was held in Nanchang, Jiangxi Province. China Fish. 2010, 32. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=8XsFQqBkIewtpCFQ9tzkVXOzT4pVmQ5LiMdhKbTSbE21t9SFOEDCjtlRZstlB-c6ghcaHfyA6qUDAhyrvYqdGpK93vfb-gLdFpsWf6Xxbqu7bdtUpjLuAlcE4i5JlmZToBcDHHHDm5vFDeAaScSX5RsfC5tlH2vrAuXYOdHzCd-8IdAOmcaUXQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Chen, K.; Du, H.; Ma, C. The Spillover Effects of Real Estate; American Economic Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.aeaweb.org/conference/2025/program/paper/4s4B26S2 (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Fang, J.; Fabinyi, M. Characteristics and Dynamics of the Freshwater Fish Market in Chengdu, China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 638997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B. The Choice Behavior in Fresh Food Retail Market: A Case Study of Consumers in China. Int. J. China Mark. 2011, 2, 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, K.; He, R.-K.; Gao, M. Design for Product-Service System Innovation of the New Fresh Retail in the Context of Chinese Urban Community. Ergon. Des. 2022, 47, 1001936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wu, T.; Budhathoki, M.; Fang, D.S.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X. Consumption Patterns and Willingness to Pay for Sustainable Aquatic Food in China. Foods 2024, 13, 2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seung, C.K.; Kim, D.-H. Examining Supply Chain for Seafood Industries Using Structural Path Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Sun, D. The innovative development path of modern aquaculture seed industry in China. Res. Agric. Mod. 2021, 42, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Li, Y.; Lai, W.; Yao, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Han, S.; Du, J.; Yao, X.; et al. Innovation and development of the aquaculture nutrition research and feed industry in China. Rev. Aquac. 2024, 16, 759–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lu, H.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, X. Aquatic products processing industry in China: Challenges and outlook. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 20, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y. Performance evaluation on aquatic product cold-chain logistics. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2015, 8, 1746–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWF. CFLP Report on Cold Chain Logistics and Refrigeration Facilities for Aquatic Products; WWF: Gland, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Long, L.; Liu, H.; Cui, M.; Zhang, C.; Liu, C. Offshore aquaculture in China. Rev. Aquac. 2024, 16, 254–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, S.; Chen, B.; Kang, H.; Huang, M. China’s aquatic product processing industry: Policy evolution and economic performance. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 58, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toai, D.B. An Empirical Analysis of China’s Aquatic Product Exports from 2018 to 2025: Trends, Challenges, and Global Trade Implications. Eur. J. Business, Econ. Manag. 2025, 1, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D. Modeling and analysis of marine product trade on the coordinated development of economy and resource in border and coastal area. J. Coast. Res. 2018, 83, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Bao, X.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, R. Recent initiatives and developments in the ecological utilization of marine resources (EUMR) in China. J. Coast. Res. 2019, 93, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X. China’s seven-decades of opening-up: Empowering growth and reforms. China Econ. 2021, 16, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwuma, N.A.; Ngoc, L.M.; Mativenga, P. The US-China trade war: Interrogating globalisation of technology. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2024, 10, 2365509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MOFCOM. China Foreign Investment Statistical Bulletin 2023; Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2023. Available online: https://images.mofcom.gov.cn/wzs/202310/20231010105622259.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Jia, C.; Ying, P. Study on Asymmetric Power Pattern of Fish Supply Chain and Its Collaborative Governance; Shanghai Ocean University: Shanghai, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wanqiu, Z.; Bin, C. Research on China’s Penaeus Vannamei Industry Value Chain—Taking Zhanjiang, Guangdong as an Example; Shanghai Ocean University: Shanghai, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.; Dey, M.M.; Laowapong, A.; Bastola, U. Price Transmission in Thai Aquaculture Product Markets: An Analysis Along Value Chain and Across Species. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2015, 19, 51–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, T.; Matsui, T.; Sakai, Y.; Yagi, N. Structural changes and imperfect competition in the supply chain of Japanese fisheries product markets. Fish. Sci. 2014, 80, 1337–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, F. A Pivotal Turning Point in the History of New China’s Fisheries Development: The March 1985 Directive Issued by the CPC Central Committee and the State Council on “Liberalizing Policies and Accelerating the Development of the Aquaculture Industry”. In Proceedings of the Thirty Years of Reform and Opening-Up in China’s Fisheries Sector, Zhoushan, Zhejiang, 29 October 2008; pp. 31–38. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=8XsFQqBkIew7F_683d7zRSAga53d2kNCVV5jZURr8UeOLSRikIO0Erku7b4QuYQs8BmrDyeieBKcMqov-Qv5WJP7HNUzgbKcMtFj2B1VWnq1nxtcuqOZ8EkkDmICHYm_7IG8A194uNznMMD90dgwmnkYIxoRIx15&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- NPCSC. Fisheries Law of the People’s Republic of China. State Council Gazette, Beijing, China. 1986, 35–40. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=8XsFQqBkIez3s4sTNSSUo1bsdTpn9UioCDG-97bps-LRP2s-tp1DJ_X0ng78p1HDHYq6Lpss9mPJ6MMtjqzOn4V-AyNZGyHymIVnfqsLDZhgj4tClBNeIPHD94P3hX975yqFKNTVmQmdFtruQJ6GoJoztNxNSpL1Rm_pRl8cMpaJ9CRrTCAKnA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Ren, B.; Li, P. From Establishing the Socialist Market Economy to Building a High-Standard Socialist Market Economy. China Rev. Polit. Econ. 2024, 15, 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T. Reflections on the Sustainable Development of China’s Fisheries Economy. China Fish. 2003, 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z. Understanding of the aquaculture license system. Jiangxi Fish. Sci. Technol. 2003, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Min, C. Overview of China’s Financial Subsidy Policies for Aquaculture During the 12th Five-Year Plan Period and Policy Outlook for the 13th Five-Year Plan. Fish. Inf. Strateg. 2017, 111. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D. The Ministry of Agriculture issued the Work Guidelines for Formulating Aquaculture Zoning Plans and the Compilation Framework. China Fish. 2017, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- MARA. Several Guidelines on Accelerating the Green Development of the Aquaculture Industry. China Fish. 2019, 7–10. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, Z.; Xu, H.; Newton, R.; Benter, A.; Fang, D.S.; Wang, C.; Little, D.; Zhang, W. Aquaculture Industry Composition, Distribution, and Development in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11331. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411331

Ma Z, Xu H, Newton R, Benter A, Fang DS, Wang C, Little D, Zhang W. Aquaculture Industry Composition, Distribution, and Development in China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11331. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411331

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Zixuan, Hao Xu, Richard Newton, Anyango Benter, Dingxi Safari Fang, Chun Wang, David Little, and Wenbo Zhang. 2025. "Aquaculture Industry Composition, Distribution, and Development in China" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11331. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411331

APA StyleMa, Z., Xu, H., Newton, R., Benter, A., Fang, D. S., Wang, C., Little, D., & Zhang, W. (2025). Aquaculture Industry Composition, Distribution, and Development in China. Sustainability, 17(24), 11331. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411331