Climate-Driven Conflicts in Nigeria: Farmers’ Strategies for Coping with Herders’ Incursion on Crop Lands

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Describe the socio-economic characteristics of farmers in the area.

- Identify herdsmen’s activities and forms of incursion on arable crop farms.

- Ascertain the effects of herders’ intrusion on the arable crop farm.

- Determine farmers’ coping strategies in response to herders’ incursion.

- Ascertain the challenges faced by farmers in adopting coping strategies against herders’ incursion.

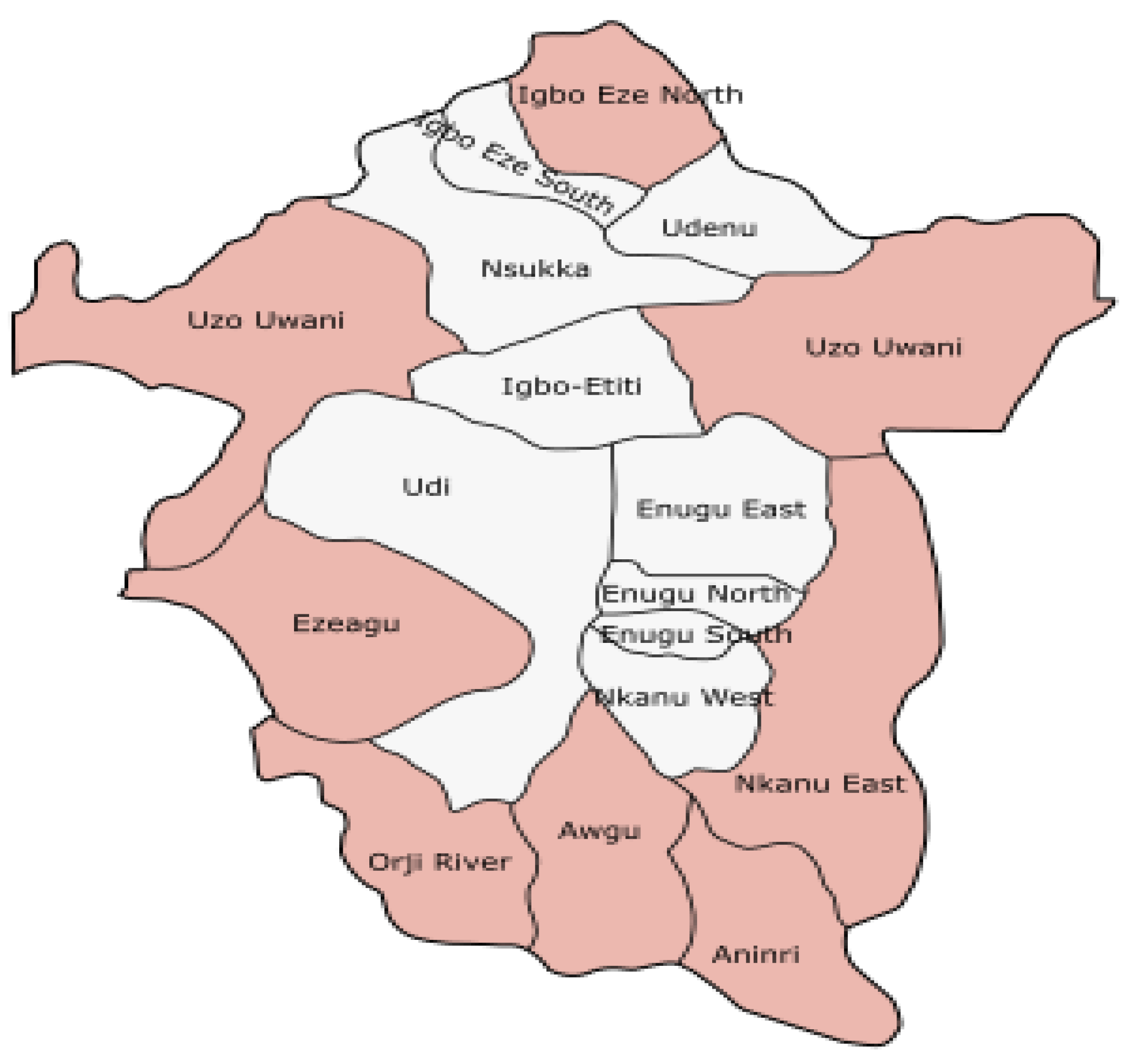

2. Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Socio-Economic Characteristics of the Respondents

3.1.1. Sex

3.1.2. Age

3.1.3. Educational Level

3.1.4. Farm Size (Plot)

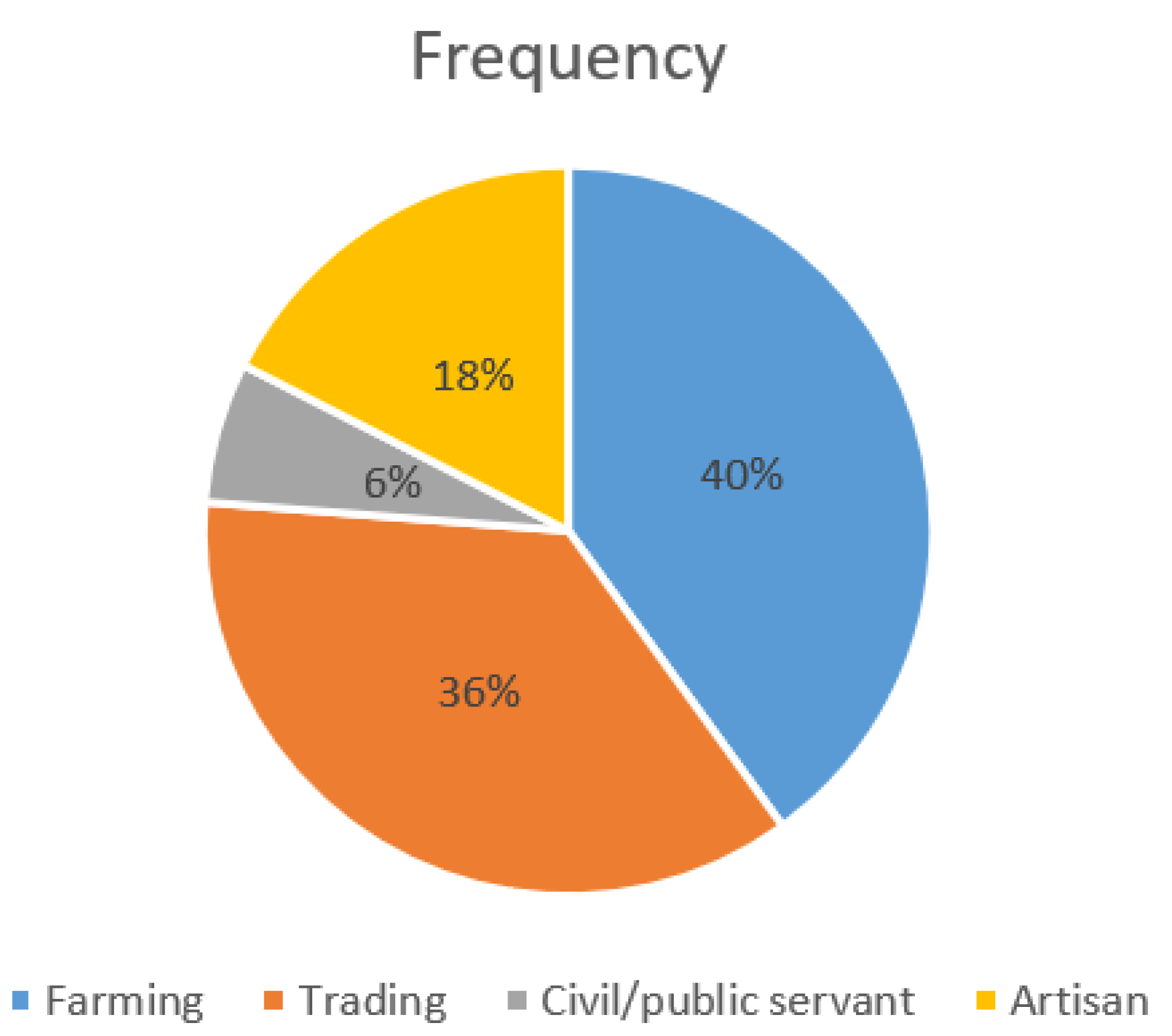

4. Primary Occupation of the Respondents

5. Recommendation

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yunusa, E.; Owoyemi, J.O. Rural Development and Resource-Based Conflict in North-Central Nigeria: Escalation, Consequences and Management. Int. J. Multi Discip. Sci. (IJ-MDS) 2025, 3, 1–25. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/390742820_Rural_Development_And_Resource-Based_Conflict_In_North-_Central_Nigeria_Escalation_Consequences_And_Management (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Froese, R.; Pinzón, C.; Aceitón, L.; Argentim, T.; Arteaga, M.; Navas-Guzmán, J.S.; Pismel, G.; Scherer, S.F.; Reutter, J.; Schilling, J.; et al. Conflicts over Land as a Risk for Social-Ecological Resilience: A Transnational Comparative Analysis in the Southwestern Amazon. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamou, C.; Ripoll-Bosch, R.; de Boer, I.J.M.; Oosting, S.J. Pastoralists in a Changing Environment: The Competition for Grazing Land in and around the W Biosphere Reserve, Benin Republic. Ambio 2018, 47, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaisi, A.; Adegbeye, M.J.; Elghandour, M.M.Y.; Melado, M.; Salem, A.Z.M. Climate Change and Agriculture: The Competition for Limited Resources amidst Crop Farmers-Livestock Herding Conflict in Nigeria—A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 272, 123104. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342965782_Climate_change_and_Agriculture_The_competition_for_limited_resources_amidst_crop_farmers-livestock_herding_conflict_in_Nigeria_-_A_review (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Nguyen, T.T.; Grote, U.; Neubacher, F.; Rahut, D.B.; Do, M.H.; Paudel, G.P. Security Risks from Climate Change and Environmental Degradation: Implications for Sustainable Land Use Transformation in the Global South. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 63, 101322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Climate Change, Hydro-Conflicts and Human Security|FP7. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/244443/reporting (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Zou, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y. An Analysis of Land Use Conflict Potentials Based on Ecological-Production-Living Function in the Southeast Coastal Area of China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 122, 107297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellens, M.K.; Diemer, A. Natural Resource Conflicts: Definition and Three Frameworks to Aid Analysis. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351174024_Natural_Resource_Conflicts_Definition_and_Three_Frameworks_to_Aid_Analysis (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Bayramov, A. Review: Dubious Nexus between Natural Resources and Conflict. J. Eurasian Stud. 2018, 9, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aysan, A.F.; Bakkar, Y.; Ul-Durar, S.; Kayani, U.N. Natural Resources Governance and Conflicts: Retrospective Analysis. Resour. Policy 2023, 85, 103942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwankwo, C.F. The Moral Economy of the Agatu “Massacre”: Reterritorializing Farmer-Herder Relations. Society 2023, 60, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bebbington, A.J.; Batterbury, S.P.J. Transnational Livelihoods and Landscapes: Political Ecologies of Globalization. Ecumene 2001, 8, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamidele, S. A New Twist to an Age-Long Friendship: The Role of Local Defence Groups in the Conflict Between Farmers and Herders. S. Afr. J. Secur. 2024, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, E.A.; Thill, A.; Kuusaana, E.D.; Mittag, A. Farmer–Herder Conflicts in Sub-Saharan Africa: Drivers, Impacts, and Resolution and Peacebuilding Strategies. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 123001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasu, H. Operationalizing the Responsibility to Protect in the Context of Civilian Protection by UN Peacekeepers. Int. Peacekeeping 2011, 18, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal, L.A. Human Security in a Post-Conflict Livelihoods Change Context: Case of Buni Yadi Northeast, Nigeria. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/383457059_Human_Security_in_a_Post-conflict_Livelihoods_Change_Context_Case_of_Buni_Yadi_Northeast_Nigeria (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Henrico, I.; Doboš, B. Shifting Sands: The Geopolitical Impact of Climate Change on Africa’s Resource Conflicts. S. Afr. Geogr. J. 2024, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig Cepero, O.; Desmidt, S.; Detges, A.; Tondel, F.; Van Ackern, P.; Foong, A.; Volkholz, J. Climate Change, Development and Security in the Central Sahel; The Barcelona Centre for International Affairs: Barcelona, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, R.; Saleh, L.; Owino, E. Pastoral Conflict on the Greener Grass? Exploring the Climate-Conflict Nexus in the Karamoja Cluster. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 119, 105287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, B.; Godesso, A.; Tesema, D. Dynamics of Pastoral Conflicts in Eastern Rift Valley of Ethiopia: Contested Boundaries, State Projects and Small Arms. Pastor. Res. Policy Pract. 2023, 13, 2–13. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/368713465_Dynamics_of_pastoral_conflicts_in_eastern_Rift_Valley_of_Ethiopia_Contested_boundaries_state_projects_and_small_arms (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Malhotra, A.; Nandigama, S.; Bhattacharya, K.S. Puhals: Outlining the Dynamics of Labour and Hired Herding among the Gaddi Pastoralists of India. Pastoralism 2022, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamidele, S. “Sweat Is Invisible in the Rain”: Civilian Joint Task Force and Counter-Insurgency in Borno State, Nigeria. Secur. Def. Q. 2020, 31, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efobi, U.; Adejumo, O.; Kim, J. Climate Change and the Farmer-Pastoralist’s Violent Conflict: Experimental Evidence from Nigeria. Ecol. Econ. 2025, 228, 108449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasona, M.J.; Omojola, A.S. Climate Change, Human Security and Communal Clashes in Nigeria; Global Environmental Change and Human Security (GECHS): Oslo, Norway, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunbode, T.O.; Jazat, J.O.; Akande, J.A. Economic Factors Affecting Environmental Pollution in Two Nigerian Cities: A Comparative Study. Sci. Prog. 2023, 106, 00368504231153489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugbega, S.K.; Aboagye, P.Y. Farmer-Herder Conflicts, Tenure Insecurity and Farmer’s Investment Decisions in Agogo, Ghana. Agric. Food Econ. 2021, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, A.A.; Amadu, L. Urbanization, Cities, and Health: The Challenges to Nigeria—A Review. Ann. Afr. Med. 2017, 16, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakana, S. Causes of Climate Change: Review Article. Glob. J. Sci. Front. Res. 2020, 20, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Okoli, A.C.; Ogayi, C.O. Herdsmen Militancy and Humanitarian Crisis in Nigeria: A Theoretical Briefing. Afr. Secur. Rev. 2018, 27, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahaya, I.; Xu, R.; Zhou, J.; Jiang, S.; Su, B.; Huang, J.; Cheng, J.; Dong, Z.; Jiang, T. Projected Patterns of Land Uses in Africa under a Warming Climate. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbule, P.O.; Okonta, E.C. How Climate Change Induced Land Conflicts and Food Insecurity in Africa: A Case of Herdsmen-Farmers Crisis in Nigeria: Climate Change, Land Conflicts, Food Insecurity, Herdsmen, Farmers, Land Policies. Afr. J. Land Policy Geospat. Sci. 2024, 7, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeleliere, E.; Antwi-Agyei, P.; Guodaar, L. Farmers Response to Climate Variability and Change in Rainfed Farming Systems: Insight from Lived Experiences of Farmers. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Li, S.; Chen, J.; Yu, H.; Yang, T.; Wang, C.; Huang, S.; Chen, H.; Ao, X. Impacts of Global Climate Change on Agricultural Production: A Comprehensive Review. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulieman, H.M. Causes and Impacts of Farmer-Herder Conflicts Through a Political Economy and Food Production Lens: Case Study in Gadarif State, Sudan. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388066353_Causes_and_impacts_of_farmer-herder_conflicts_through_a_political_economy_and_food_production_lens_Case_study_in_Gadarif_State_Sudan (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Mohammed, I. Farmers-Herders Conflict and Human Security in Northeast, Nigeria. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382817092_FARMERS-HERDERS_CONFLICT_AND_HUMAN_SECURITY_IN_NORTHEAST_NIGERIA (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Nabweteme, H.; Bostedt, G.; Turinawe, A. Livelihood Security Shocks and Coping Strategies in the Drylands of Kenya and Uganda—A Seasonal Analysis. Dev. Stud. Res. 2025, 12, 2516434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadare, O.; Srinivasan, C.; Zanello, G. Livestock Diversification Mitigates the Impact of Farmer-Herder Conflicts on Animal-Source Foods Consumption in Nigeria. Food Policy 2024, 122, 102586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adisa, B.O.; Famakinwa, M.; Adeloye, K.A.; Adigun, A.O. Crop Farmers’ Coping Strategies for Mitigating Conflicts with Cattle Herders: Evidence from Osun State, Nigeria. Agric. Trop. Subtrop. 2022, 55, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osimen, G.U.; Mary, E.F.; Oluwatobi, D.I. Herdsmen and Farmers Conflict in Nigeria: A Threat to Peace-Building and National Security in West Africa. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/361857460_Herdsmen_and_Farmers_Conflict_in_Nigeria_A_Threat_to_Peace-building_and_National_Security_in_West_Africa (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Linus, O.O.; Alex, A.A. Resolving Farmers-Herders Conflict Through Security-Necessitated Technologies in Nigeria. ASRIC J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2023, 4, 254–264. [Google Scholar]

- Gashure, S. Adaptation Strategies of Smallholder Farmers to Climate Variability and Change in Konso, Ethiopia. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19203. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/383235677_Adaptation_strategies_of_smallholder_farmers_to_climate_variability_and_change_in_Konso_Ethiopia (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Bekele, M. Resistance as Agency: Reimagining Participation in Forest Landscape Restoration in Tigray, Ethiopia. Trees For. People 2025, 21, 100967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asule, P.A.; Musafiri, C.; Nyabuga, G.; Kiai, W.; Kiboi, M.; Nicolay, G.; Ngetich, F.K. Awareness and Adoption of Climate-Resilient Practices by Smallholder Farmers in Central and Upper Eastern Kenya. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orangi, P.N.; Nomura, H.; Nyambok, L.O. Nurturing Self-Efficacy through Inclusivity and Support Systems: Improving Livelihoods of Vulnerable Farmers via SHEP Approach in Kenya. Sci. Afr. 2025, 29, e02871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.D.; Ayatunde, A.A.; Patterson, E.D., III. Livelihood Transitions and the Changing Nature of Farmer–Herder Conflict in Sahelian West Africa. J. Dev. Stud. 2011, 47, 183–206. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/51053310_Livelihood_Transitions_and_the_Changing_Nature_of_Farmer-Herder_Conflict_in_Sahelian_West_Africa (accessed on 1 October 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfadul, H.; Siddig, K.; Ahmed, M.; Abushama, H. Sustainable Livestock Development in Sudan; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shumi, G.; Loos, J.; Fischer, J. Applying Social-Ecological System Resilience Principles to the Context of Woody Vegetation Management in Smallholder Farming Landscapes of the Global South. Ecosyst. People 2024, 20, 2339222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xue, J.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, H.; Li, X.; Chang, J.; Liu, X.; Yao, L. An Adaptive Cycle Resilience Perspective to Understand the Regime Shifts of Social-Ecological System Interactions over the Past Two Millennia in the Tarim River Basin. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, A. Capitals and Capabilities: A Framework for Analyzing Peasant Viability, Rural Livelihoods and Poverty. World Dev. 1999, 27, 2021–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcells, L.; Stanton, J.A. Violence Against Civilians During Armed Conflict: Moving Beyond the Macro- and Micro-Level Divide. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2021, 24, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besaw, C.; Ritter, K.; Tezcür, G.M. Beyond Collateral Damage: The Politics of Civilian Victimization in a Civil War. Glob. Stud. Q. 2023, 3, ksad050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwalyagile, N.; Jeckoniah, J.N.; Salanga, R.J. Understanding Gender Power Relations in Irrigation Resource Access and Decision-Making in Small-Scale Irrigation Schemes in Mbarali District, Tanzania. IIMT J. Manag. 2025, 18, 101390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaye, W.; Fuseini, M.; Boadu, P.; Asafu-Adjaye, N.Y. Bridging the Gender Gap in Agricultural Development through Gender Responsive Extension and Rural Advisory Services Delivery in Ghana. J. Gend. Stud. 2017, 28, 1–19. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322104494_Bridging_the_gender_gap_in_agricultural_development_through_gender_responsive_extension_and_rural_advisory_services_delivery_in_Ghana (accessed on 6 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Gomes, D.; Jesus, M.; Rosa, R.; Bandeira, C.; da Costa, C.A. Women in Family Farming: Evidence from a Qualitative Study in Two Portuguese Inner Regions. Front. Sociol. 2022, 7, 939590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuryati, M.N.; Djono, A.; Chotimah, N. The Role of Women in Empowering Family Economy Through Agriculture in Koro Village. Interdiscip. Soc. Stud. 2022, 1, 726–732. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/361850254_THE_ROLE_OF_WOMEN_IN_EMPOWERING_FAMILY_ECONOMY_THROUGH_AGRICULTURE_IN_KORO_VILLAGE (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Amare, M.; Abay, K.A.; Berhane, G.; Andam, K.S.; Adeyanju, D. Conflicts, Crop Choice, and Agricultural Investments: Empirical Evidence from Nigeria. Land Use Policy 2025, 148, 107391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutu Sakketa, T. Urbanisation and Rural Development in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review of Pathways and Impacts. Res. Glob. 2023, 6, 100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maduekwe, C.A. World Bank Assisted Intervention Development Projects on Poverty Alleviation in Nigeria: An Impact Evaluation of National FADAMA III in Enugu State. 2023. Available online: https://lup.lub.lu.se/student-papers/search/publication/9116724 (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Udoh, E.; Akpan, S.B.; Francis, U.K. Assessment of Sustainable Livelihood Assets of Farming Households in Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. J. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 10, 83. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318789747_Assessment_of_Sustainable_Livelihood_Assets_of_Farming_Households_in_Akwa_Ibom_State_Nigeria (accessed on 6 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Sahar, A.; Kaunert, C. Higher Education as a Catalyst of Peacebuilding in Violence and Conflict-Affected Contexts: The Case of Afghanistan. Peacebuilding 2021, 9, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajogbeje, K.; Sylwester, K. How Conflict Affects Education: Differences between Boko Haram and Farmer-Herder Conflicts in Nigeria. World Dev. 2024, 177, 106540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asresie, A.; Seid, A.; Muhie, S.H.; Hassen, S. War and Its Impact on Farmers’ Crop and Livestock Productivity in South Wollo Zone, Northeastern Ethiopia. Sci. Afr. 2025, 27, e02589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejlumyan, D.; Maru, T.; Kusadokoro, M.; Urutyan, V.; Yeghiazaryan, G.; Kawabata, Y. Understanding Farmers’ Intentions to Abandon Farmland in Mountainous Regions of Armenia. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 391, 126573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashagidigbi, W.M.; Ishola, T.M.; Omotayo, A.O. Gender and Occupation of Household Head as Major Determinants of Malnutrition among Children in Nigeria. Sci. Afr. 2022, 16, e01159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begho, T.; Begho, M.O. The Occupation of Last Resort? Determinants of Farming Choices of Small Farmers in Nigeria. Int. J. Rural Manag. 2023, 19, 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Almost Half the World’s Population Lives in Households Linked to Agrifood Systems. Available online: https://www.fao.org/newsroom/detail/almost-half-the-world-s-population-lives-in-households-linked-to-agrifood-systems/en (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Adeoye, P.A.; Afolaranmi, T.O.; Ofili, A.N.; Chirdan, O.O.; Agbo, H.A.; Adeoye, L.T.; Su, T.T. Socio-Demographic Predictors of Food Security among Rural Households in Langai District in Plateau-Nigeria: A Cross-Sectional Study. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2022, 43, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uduji, J.I.; Okolo-Obasi, N.E.V.; Uduji, J.U.; Odoh, L.C.; Otei, D.C.; Obi-Anike, H.O.; Nwanmuoh, E.E.; Okezie, K.O.; Ngwuoke, O.U.; Ojiula, B.U.; et al. Herder-Farmer Conflict in Sub-Saharan Africa and Corporate Social Responsibility in Nigeria’s Oil Host Communities. Local Environ. 2024, 29, 1244–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesele, S.A.; Mechri, M.; Okon, M.A.; Isimikalu, T.O.; Wassif, O.M.; Asamoah, E.; Ahmad, H.A.; Moepi, P.I.; Gabasawa, A.I.; Bello, S.K.; et al. Current Problems Leading to Soil Degradation in Africa: Raising Awareness and Finding Potential Solutions. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2025, 76, e70069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugari, E.; Mamabolo, E.; Mathebula, N.; Mogale, T.E.; Mashala, M.J.; Mabitsela, K.; Ayisi, K.K. Barriers and Enablers to Implementing On-Farm Sustainable Land Management (SLM) Practices among Smallholder Farmers in Mphanama, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Sci. Afr. 2025, 28, e02750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R.K.; Purohit, S.; Alam, E.; Islam, M.K. Advancements in Soil Management: Optimizing Crop Production through Interdisciplinary Approaches. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 18, 101528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brottem, L. The Growing Complexity of Farmer-Herder Conflict in West and Central Africa; Africa Center: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Obuzor, M.; Chukwu, S.G.A.; Chukwu, C.C. An Examination of The Threats of Climate Change, Herdsmen Migration and the Proliferation of Arms: Issues, Challenges and the Way Forward in Southeast Nigeria. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343136273_An_Examination_of_The_Threats_of_Climate_Change_Herdsmen_Migration_and_the_Proliferation_of_Arms_Issues_Challenges_and_the_Way_Forward_in_Southeast_Nigeria (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Richard, A.T. Pastoralists and Farmers Conflict in Benue State: Changes in Climate in Northern Nigeria as a Contributing Factor. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2023, 17, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antriyandarti, E.; Suprihatin, D.N.; Pangesti, A.W.; Samputra, P.L. The Dual Role of Women in Food Security and Agriculture in Responding to Climate Change: Empirical Evidence from Rural Java. Environ. Chall. 2024, 14, 100852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, B.; Abdullahi, M.M. Farmers–Herdsmen Conflict, Cattle Rustling, and Banditry: The Dialectics of Insecurity in Anka and Maradun Local Government Area of Zamfara State, Nigeria. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211040117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tope, T.; Olutumise, A.I.; Oguntade, A.; Oladoyin, O.P. Herdsmen-Farmer Conflicts and Their Effects on Agricultural Productivity and Rural Livelihoods. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/389937362_Herdsmen-Farmer_Conflicts_and_Their_Effects_on_Agricultural_Productivity_and_Rural_Livelihoods (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Sowunmi, F.A.; Odaudu, M.N.; Awoyemi, A.E. Assessing the Economic and Social Consequences of Crop Farmer-Herder Conflicts on Crop Production in Benue State. Agri. Res. 2025, 29, 556440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnaji, A.; Ma, W.; Ratna, N.; Renwick, A. Farmer-Herder Conflicts and Food Insecurity: Evidence from Rural Nigeria. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2022, 51, 391–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.; Adelaja, A. Armed Conflicts, Forced Displacement and Food Security in Host Communities. World Dev. 2022, 158, 105991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardo, E.; Dorward, P.; Garforth, C.; Sutcliffe, C.; Van Hulst, F. Conflict-Induced Displacement as a Catalyst for Agricultural Innovation: Findings from South Sudan. Land Use Policy 2020, 90, 104272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slayi, M.; Zhou, L.; Dzvene, A.R.; Mpanyaro, Z. Drivers and Consequences of Land Degradation on Livestock Productivity in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Literature Review. Land 2024, 13, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.A.; Abebe, G.K. Rural Displacement and Its Implications on Livelihoods and Food Insecurity: The Case of Inter-Riverine Communities in Somalia. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambo, E.; Zhang, C.-S.; Tazemda, G.B.; Fankep, B.; Tappa, N.T.; Bkamko, C.F.B.; Tsague, L.M.; Tchemembe, D.; Ngazoue, E.F.; Korie, K.K.; et al. Triple-Crises-Induced Food Insecurity: Systematic Understanding and Resilience Building Approaches in Africa. Sci. One Health 2023, 2, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babarinde, S.A. Assessing the Effects of Fulani Herdsmen Violence on Farmer’s Productivity in Nigeria: A Mixed Method Analogy. SSRN Electron. J. 2021. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3935703 (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Chowdhury, M.R.; Latif, S. What Is Coping Theory? Definition & Worksheets. 2019. Available online: https://positivepsychology.com/ (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Holahan, C.J.; Moos, R.H. Adaptive Coping—An Overview | ScienceDirect Topics. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/psychology/adaptive-coping (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Joseph, W. Coping Mechanisms in Psychology: An In-Depth Exploration of Strategies for Managing Stress and Adversity. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/391154953_Coping_Mechanisms_in_Psychology_An_In-Depth_Exploration_of_Strategies_for_Managing_Stress_and_Adversity (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Zhu, X.; Wang, G. Impact of Agricultural Cooperatives on Farmers’ Collective Action: A Study Based on the Socio-Ecological System Framework. Agriculture 2024, 14, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Marini, M.A.; Rahut, D.B. Farmers’ Organizations and Sustainable Development: An Introduction. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2023, 94, 683–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burudi, J.W.; Tormáné Kovács, E.; Katona, K. Wildlife Fences to Mitigate Human–Wildlife Conflicts in Africa: A Literature Analysis. Diversity 2025, 17, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerbacher, A.; Lippert, C.; Kuenzang, J.; Subedi, K. Low-Cost Electric Fencing for Peaceful Coexistence: An Analysis of Human-Wildlife Conflict Mitigation Strategies in Smallholder Agriculture. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 255, 108919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krendelsberger, A.; Alpizar, F.; Syll, M.M.A.; van Dijk, H. Climate Change, Collective Shocks, and Intra-Community Cooperation: Evidence from a Public Good Experiment with Farmers and Pastoralists. World Dev. 2025, 189, 106941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazell, P.; Timu, A.G. What’s Holding Back Private Sector Agricultural Insurance; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rutt, L. Farmers and Farmers’ Associations in Developing Countries and Their Use of Modern Financial Instruments. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/23743480_Farmers_and_farmers'_associations_in_developing_countries_and_their_use_of_modern_financial_instruments (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Barange, L. Sustainable Agricultural Development: Roots of Peacebuilding. Available online: https://alliancebioversityciat.org/stories/sustainable-agricultural-development-roots-peacebuilding (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Geier, B. Gardens Instead of Machine Guns–Making Peace through Organic Farming. Available online: https://www.welthungerhilfe.org/global-food-journal/rubrics/agricultural-food-policy/vegetables-instead-of-guns-organic-farming-for-peace (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Girma, Y.; Kuma, B. A Meta Analysis on the Effect of Agricultural Extension on Farmers’ Market Participation in Ethiopia. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 7, 100253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Connor, J.D. Impact of Agricultural Extension Services on Fertilizer Use and Farmers’ Welfare: Evidence from Bangladesh. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Crisis Group Managing Vigilantism in Nigeria: A Near-Term Necessity|International Crisis Group. Available online: https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/managing-vigilantism-nigeria-near-term-necessity (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Saheed, O. Security Funding, Accountability and Internal Security Management in Nigeria. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334643035_Security_Funding_Accountability_and_Internal_Security_Management_in_Nigeria (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Marfo, S.; Bolaji, M.H.A.-G.; Tseer, T. A Human Security Angle of Conflicts: The Case of Farmer–Herder Conflict in Ghana. Int. Ann. Criminol. 2022, 60, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Nichol, J.E. Changes in Agricultural and Grazing Land, and Insights for Mitigating Farmer-Herder Conflict in West Africa. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 222, 104383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwuno, O.J. Examining the Nexus of Extra-Judicial Killings and Security Crisis in South-East Nigeria: Beyond the Law. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/392398262_Examining_the_nexus_of_extra-Judicial_Killings_and_Security_Crisis_in_South-East_Nigeria_Beyond_the_Law (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Ekundayo, O.B. Beyond Law Making: Law Enforcement as a Critical Tool in Tackling Fulani Herdsmen Crisis in Nigeria. Lesotho Law J. 2022, 27, 81–159. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-lesotho_v27_n1_a4 (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Joshua, M.; Patrick, K.; Maikomo, M.J. Banditry and Its Implications on the Livelihood of Small Scale Famers in Nigeria: A Study of Taraba State, Nigeria. Soc. Sci. 2024, 7, 443–464. [Google Scholar]

- Ajala, O. New Drivers of Conflict in Nigeria: An Analysis of the Clashes between Farmers and Pastoralists. Third World Q. 2020, 41, 1–19. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344765216_New_drivers_of_conflict_in_Nigeria_an_analysis_of_the_clashes_between_farmers_and_pastoralists (accessed on 24 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Drew, J.; Knutsson, P. Boundary-Making, Tenure Insecurity, and Conflict: Regional Dynamics of Land Tenure Change and Commodification in East Africa’s Pastoralist Rangelands. World Dev. 2025, 194, 107068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwozor, A.; Olanrewaju, J.S.; Oshewolo, S.; Okidu, O. Herder-Farmer Conflicts: The Politicization of Violence and Evolving Security Measures in Nigeria. Afr. Secur. 2021, 14, 1–25. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350212284_Herder-Farmer_Conflicts_The_Politicization_of_Violence_and_Evolving_Security_Measures_in_Nigeria (accessed on 22 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ezemenaka, K.E.; Ekumaoko, C.E. Contextualising the Fulani-Herdsmen Conflict in Nigeria. Cent. Eur. J. Int. Secur. Stud. 2025, 12, 30–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, M.M.; Umar, B.F.; Hamisu, S. Farmer-Herder Conflicts Management: The Role of Traditional Institution in Borno State, Nigeriia. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/375697659_Farmer_-_Herder_Conflicts_Management_The_Role_of_Traditional_Institution_in_Borno_State_Nigeriia (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Idris, A.B.; Najmudeen, A.M. Herders-Farmers Conflict: A |Review of Consequences and Mitigation Strategies on Food Security in Nigeria. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357327094_Herders-Farmers_Conflict_A_Review_of_Consequences_and_Mitigation_Strategies_on_Food_Security_in_Nigeria (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Beltran-Tolosa, L.M.; Ccruz-Garcia, G.S.; Ocampo, J.; Pradhan, P.; Quintero, M. Rural Livelihood Diversification Is Associated with Lower Vulnerability to Climate Change in the Andean-Amazon Foothills. Available online: http://ouci.dntb.gov.ua/en/works/l1g8Qk57/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Olatinwo, L.K.; Komolafe, S.E.; Faronbi, K.O. Post Farmer-Herder Conflict Management and Relief Strategies of Farmers in Nigeria. J. Agric. Sci.–Sri Lanka 2025, 20, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, S.; Kyereh, B.; Pouliot, M.; Derkyi, M. Effect of Farmer–Herder Conflict Adaptation Strategies on Multidimensional Poverty and Subjective Wellbeing in Ghana. Afr. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2024, 19, 181–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, C.S.; Keling, W.; Ho, P.L.; Omar, Q. Technology Readiness of Farmers in Sarawak: The Effect of Gender, Age, and Educational Level. Inf. Dev. 2025, 41, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woh, P.Y.; Sengxayalath, P.; Van Pham Thi, K. Impact of Generational Differences on Rice Farmer’s Perception and Challenges in Champassak, Laos. Agric. Food Secur. 2025, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvivier, P.; Tescar, R.P.; Halliday, C.; Murphy, M.M.; Guell, C.; Howitt, C.; Augustus, E.; Haynes, E.; Unwin, N. Differences in Income, Farm Size and Nutritional Status between Female and Male Farmers in a Region of Haiti. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1275705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 45 | 56.3 | |

| Female | 35 | 43.8 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| ≤35 | 8 | 10.0 | |

| 36–45 | 23 | 29.0 | |

| 46–55 | 28 | 35.0 | 49.50 |

| 56–65 | 16 | 20.0 | |

| ≥65 | 5 | 6.0 | |

| Educational level | |||

| No formal education | 12 | 15.0 | |

| Primary | 27 | 33.8 | |

| Secondary | 34 | 42.5 | 9.80 |

| Tertiary | 7 | 8.8 | |

| Farm size (plot) | |||

| ≤10 | 71 | 88.8 | |

| 11–20 | 6 | 7.5 | 5.10 |

| ≥20 | 3 | 3.8 |

| Activities of Herdsmen on Arable Crop Farms | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Allowing cattle to feed on growing crops | 80 | 100.0 |

| Overgrazing of farmlands | 80 | 100.0 |

| Using cattle to trample on crop beds, ridges, or mounds | 80 | 100.0 |

| Pollution of farms with defecations | 80 | 100.0 |

| Harvesting of crops to feed cattle | 77 | 96.3 |

| Intimidation of the farmers on the farm | 75 | 95.0 |

| Building of settlements around the farms | 74 | 92.5 |

| Sexual violence against women farmers | 42 | 52.5 |

| Cutting down crops on the farms | 32 | 40.0 |

| Pollution of water points around the farms | 31 | 38.8 |

| Kidnapping of farmers | 19 | 23.8 |

| Stealing of farm produce | 9 | 11.3 |

| Burning of farms | 6 | 7.5 |

| Use of a cutlass to hurt the farmers | 5 | 6.3 |

| Shooting of farmers on the farm | 3 | 3.8 |

| Effects of Herdsmen’s Intrusion on Arable Crop Production | Economic/Yield Loss Effect | Migration/Environmental Hazard Effect | Assault/Health Hazard Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loss of income from the farm | 0.690 | 0.110 | 0.186 |

| Destruction of crops | 0.847 | 0.095 | 0.107 |

| Reduction in farm output | 0.861 | 0.098 | 0.115 |

| Scarcity of food in the community | 0.873 | 0.001 | −0.077 |

| Hike in prices of food crops | 0.788 | 0.023 | −0.135 |

| Loss of peace in the community | 0.912 | 0.072 | 0.031 |

| Pollution of farms and their environments | 0.912 | 0.072 | 0.031 |

| Reduction in the number of farmers through abduction | 0.827 | 0.024 | −0.100 |

| Low participation in farm production | 0.690 | 0.110 | 0.186 |

| Discouragement of innovation on the farm | 0.860 | 0.028 | −0.028 |

| Loss of farmers’ properties, like farm implements and farmsteads | −0.077 | −0.687 | 0.160 |

| Maiming of farmers | 0.293 | −0.662 | 0.395 |

| Infestation of farms with pests and diseases | −0.157 | 0.547 | −0.165 |

| Loss of biodiversity on the farm | −0.054 | 0.753 | 0.204 |

| Displacement of farmers from their home/farmstead | −0.302 | 0.661 | 0.290 |

| Increase in the crime rate in the community | −0.039 | 0.048 | 0.533 |

| Causes anxiety, depression, or emotional trauma to farmers | −0.061 | 0.202 | −0.401 |

| Soil compartment due to trampling by cattle | −0.042 | −0.007 | 0.582 |

| Overdependence on other people in the community | −0.158 | 0.337 | 0.429 |

| Loss of farmer’s life | −0.195 | −0.178 | 0.702 |

| Farmers’ Coping Strategies to Herder Incursion on Arable Crop Farms | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Cultivating a small area of land around homes | 78 | 97.5 |

| Accept whatever remains from the affected farms | 75 | 93.8 |

| Going to farms in groups | 74 | 92.5 |

| Fencing/barricading of the farm | 67 | 83.8 |

| Possession of multiple farms | 66 | 82.5 |

| Use of local security | 52 | 65.0 |

| Receive remittance from family and friends | 49 | 61.3 |

| Remittance from union/association | 47 | 58.8 |

| Praying for peace | 44 | 55.0 |

| Reallocation/relocation to new farmland | 38 | 47.5 |

| Diversification to another job | 36 | 45.0 |

| Reduce growing crops in places affected by attack | 21 | 26.3 |

| Verbal warning/engaging in dialogue with the herders | 13 | 16.3 |

| Early harvesting of crops | 7 | 8.8 |

| Engaging in physical combat with herders | 5 | 6.3 |

| Receive compensation from an insurance firm | 5 | 6.3 |

| Borrow from banks | 5 | 6.3 |

| Killing of cattle with poison | 4 | 5.0 |

| Avoid dry seasons planting | 4 | 5.0 |

| Planting of early-maturing crops | 3 | 3.8 |

| Selling of farms | 3 | 3.8 |

| Avoid planting in riverine areas | 2 | 2.5 |

| Receive compensation from the government | 2 | 2.5 |

| Sought litigation | 1 | 1.3 |

| Appeasement of the gods | 1 | 1.3 |

| Effectiveness of the Coping Strategies Used by the Farmers | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Cultivating a small area of land around homes | 3.90 * | 0.628 |

| Going to farms in groups | 3.37 * | 1.354 |

| Possession of multiple farms | 2.96 * | 1.732 |

| Remittance from union/association | 2.21 * | 1.973 |

| Receive remittance from family and friends | 2.14 * | 1.921 |

| Accept whatever remains from the farm | 1.95 | 1.509 |

| Diversification to another job | 1.75 | 1.978 |

| Use of local security | 0.40 | 0.936 |

| Fencing/barricading of the farm | 0.56 | 1.281 |

| Reallocation/relocation to new farmland | 0.50 | 1.232 |

| Verbal warning/engaging in dialogue with herders | 0.05 | 1.232 |

| Engaging in physical combat with herders | 0.21 | 0.882 |

| Planting of early-maturing crops | 0.10 | 0.628 |

| Praying for peace | 1.10 | 1.239 |

| Killing of cattle with poison | 0.20 | 0.877 |

| Reduce growing crops in places far from homes | 0.79 | 1.540 |

| Avoid dry seasons | 0.10 | 0.565 |

| Avoid planting in riverine areas | 0.05 | 0.314 |

| Early harvesting of crops | 0.29 | 0.996 |

| Receive compensation from an insurance firm | 0.10 | 0.565 |

| Sought litigation | 0.04 | 0.335 |

| Borrow from banks | 0.10 | 0.628 |

| Selling of farms | 0.05 | 0.314 |

| Appeasement of the gods | 0.03 | 0.224 |

| Receive compensation from the government | 0.00 | 0.000 |

| Arrest and prosecution of herders | 0.00 | 0.000 |

| Planting of toxic plants on the farm (e.g., tobacco, coaster plants) | 0.00 | 0.000 |

| Use of charms | 0.00 | 0.000 |

| Poisoning of cattle | 0.00 | 0.000 |

| Challenges of Farmers to the Coping Strategies | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient inspection/patrol of the vigilantes | 3.91 * | 0.508 |

| Lack of land around homes | 3.87 * | 0.663 |

| Lack of firm protection by the police and law | 3.82 * | 0.742 |

| Illegal acquisition of weapons by the herders | 3.80 * | 0.877 |

| Accepting bribes by the local leaders/police | 3.53 * | 0.914 |

| Lack of training on coping strategies | 2.59 * | 0.910 |

| Lack of income for fencing the farm | 1.56 | 1.764 |

| Lack of an insurance firm | 0.76 | 1.314 |

| Lack of weapons to fight herders | 0.60 | 1.208 |

| Variables | Farmers’ Coping Strategies | Age | Sex | Farm Size (Plots) | Educational Level | Primary Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmers’ coping strategies | 1 | 0.019 | −0.121 | 0.262 * | −0.103 | −0.152 |

| Age | 0.019 | 1 | −0.023 | 0.010 | −0.262 * | −0.011 |

| Sex | −0.121 | −0.023 | 1 | −0.282 | 0.083 | 0.330 |

| Farm size | 0.262 * | 0.010 | −0.282 * | 1 | 0.021 | −0.175 |

| Educational level | −0.103 | −0.262 * | 0.083 | 0.021 | 1 | 0.268 |

| Primary occupation | −0.152 | −0.011 | 0.330 | −0.175 | 0.268 * | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eke, O.G.; Moudry, J.; Eze, F.O.; Obazi, S.A.; Ifoh, I.P.; Mukosha, C.E.; Ntezimana, M.G.; Muhammad, A. Climate-Driven Conflicts in Nigeria: Farmers’ Strategies for Coping with Herders’ Incursion on Crop Lands. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11316. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411316

Eke OG, Moudry J, Eze FO, Obazi SA, Ifoh IP, Mukosha CE, Ntezimana MG, Muhammad A. Climate-Driven Conflicts in Nigeria: Farmers’ Strategies for Coping with Herders’ Incursion on Crop Lands. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11316. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411316

Chicago/Turabian StyleEke, Okechukwu George, Jan Moudry, Festus Onyebuchi Eze, Sunday Alagba Obazi, Ifechukwu Precious Ifoh, Chisenga Emmanuel Mukosha, Marie Grace Ntezimana, and Atif Muhammad. 2025. "Climate-Driven Conflicts in Nigeria: Farmers’ Strategies for Coping with Herders’ Incursion on Crop Lands" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11316. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411316

APA StyleEke, O. G., Moudry, J., Eze, F. O., Obazi, S. A., Ifoh, I. P., Mukosha, C. E., Ntezimana, M. G., & Muhammad, A. (2025). Climate-Driven Conflicts in Nigeria: Farmers’ Strategies for Coping with Herders’ Incursion on Crop Lands. Sustainability, 17(24), 11316. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411316