1. Introduction

In the grand narrative of global sustainable development, human behavior is now recognized as a critical factor in mitigating ecological degradation. Elevating public environmental awareness is a crucial first step, yet bridging the gap between awareness and tangible action remains a formidable challenge. This puzzle is particularly pressing in the world’s vast rural landscapes [

1], which function not merely as ecological strongholds but as social-ecological systems where residents’ environmental perceptions, willingness, and ultimate participation directly dictate the feasibility of sustainability goals [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Understanding the drivers of environmental action in these contexts is thus a fundamental key to effective global governance.

Effective rural environmental governance must address both local ecological issues and the distinctive knowledge systems of residents. While formal governance structures exist, the profound—if sometimes inconsistent—environmental knowledge of rural residents, rooted in daily practice, provides crucial insights for addressing local challenges [

6,

7,

8]. Nonetheless, a gap often persists in their understanding of broader or global environmental concerns, underscoring the need to enhance comprehension of these concepts [

9,

10]. Equally critical is empowering residents with the resources and platforms for meaningful participation, thereby facilitating a shift from top-down directives to more inclusive and participatory models.

Environmental cognition—comprising the recognition, evaluation, and strategic understanding of environmental issues—forms the bedrock of protective behavior [

11,

12]. However, enhanced cognition alone is an insufficient driver of eco-friendly actions [

13,

14,

15]. Personal values, social pressures, and behavioral costs critically mediate the translation of knowledge into practice [

16]. This gap is especially pronounced in rural settings, where diverse educational backgrounds, cultural traditions, and uneven access to information create a particularly intricate relationship between awareness and action [

17]. A multifaceted approach is therefore essential to effectively bridge this divide in rural environments.

Comparative research from diverse global contexts reveals varied approaches to bridging this cognition–action gap. In rural communities of South Asia and East Africa, for instance, the integration of local ecological knowledge with formal governance through community-based programs (e.g., forest user groups) has shown promise in aligning individual and collective environmental actions [

18]. Conversely, interventions in many developed countries often emphasize well-established infrastructure, consistent economic incentives, and formal environmental education to facilitate pro-environmental choices [

19,

20]. These contrasting strategies underscore that the pathways from cognition to action are not universal but are profoundly shaped by the local institutional, economic, and cultural fabric. This global perspective reinforces the critical need for context-specific investigations, such as the present study in Li County, to decipher the unique mechanisms that may either bridge or widen this gap in under-researched mountainous regions of China.

The willingness to participate in environmental protection reflects an individual’s or group’s inclination towards engaging in conservation behaviors [

21]. This inclination is shaped by environmental perceptions, personal values, social influences, and past experiences with environmental behaviors [

22]. Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior posits that behavioral intentions are influenced by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived control over behavior [

23]. This theory has been extensively utilized in environmental behavior research to predict and explain the willingness to engage in environmental activities [

24,

25]. However, while the theory provides a robust framework, it often overlooks the unique socio-economic and cultural contexts of rural areas that can significantly alter the dynamics of environmental participation. Therefore, it is crucial to contextualize these findings within the specific challenges and opportunities present in rural environments to develop more effective strategies for enhancing environmental participation.

In rural areas, willingness to engage in environmental activities is shaped by socioeconomic structure, education levels, and local environmental complexity. Despite farmers’ often profound understanding of livelihood-related environmental issues, this knowledge frequently fails to translate into action due to multiple barriers. These include limited access to resources, technology, and actionable information, which collectively hinder effective participation in environmental governance [

26,

27]. Furthermore, economic constraints impose significant behavioral costs, preventing the conversion of willingness into practical action and widening the value-behavior gap [

28,

29]. A deeper understanding of these barriers is therefore essential to enhance environmental participation in rural contexts.

Environmental participation behavior refers to actions undertaken by individuals or groups to protect the environment [

30,

31]. A significant challenge in this research domain is the ‘value-behavior gap,’ which necessitates thorough examination. According to social practice theory, environmental behavior is influenced by individual perceptions, social structures, and inherent practices. Social norms and behavioral challenges, particularly in rural communities, play a pivotal role in shaping these behaviors [

32,

33]. Traditional perceptions and norms may either hinder or encourage environmental actions. For instance, waste recycling might not be fully embraced in regions where direct waste disposal is common practice [

34]. Moreover, environmental practices like waste management not only preserve the environment but also enhance ecosystem services, benefiting those who engage in such behaviors. These findings underscore the complexity of translating environmental awareness into action and highlight the need for tailored interventions to address specific community norms and practices.

The difficulty level in participating in environmental behavior significantly impacts rural residents’ choices. If waste recycling and disposal require considerable effort, residents may prefer simpler methods like direct disposal. Furthermore, the availability of appropriate infrastructure is a crucial factor. The absence or inadequacy of such infrastructure presents substantial challenges, limiting residents’ ability to engage in desired environmental behaviors. This underscores the necessity for policy interventions to improve infrastructure and support sustainable practices in rural areas, ensuring that environmental participation is both feasible and practical for residents.

Social cognitive theory and the theory of planned behavior offer critical frameworks for understanding pro-environmental behavior. While the former emphasizes how environmental cognition can motivate participation [

35,

36], the latter identifies behavioral intention—shaped by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control—as the key predictor of action [

37]. Therefore, interventions aimed at shaping these foundational factors can effectively promote environmentally friendly behaviors. Although improving cognition can strengthen intention and thereby promote pro-environmental behavior [

38], this pathway is often mediated in rural contexts. There, factors such as economic conditions, geographic isolation, and livelihood characteristics can override intention by altering the actual costs, difficulties, and perceived control associated with environmental participation [

39,

40]. Therefore, effectively addressing barriers to action requires a multifaceted approach that accounts for these contextual realities.

To effectively stimulate rural residents’ participation in environmental governance, it is crucial to consider unique local factors—such as socio-economic characteristics, geography, and land use—while addressing existing barriers. A key challenge lies in understanding the interconnected dynamics among environmental cognition, willingness to participate, and actual behavior. Given the significant challenges faced by rural areas in developing countries, where comprehensive understanding is often hindered by limited data and complex socio-political contexts, exploring these relationships in a specific setting is imperative. This study therefore focuses on Li County, Sichuan Province, China, an area characterized by diverse topography and undergoing socio-economic changes driven by tourism and agriculture. The intricate relationship between farmers and government bodies here complicates governance efforts, making it an ideal context to unravel the cognitive and behavioral aspects of farmers’ environmental participation. The research aims to provide valuable insights for similar regions and inform effective policy-making.

Our study surveyed 589 local villagers in mountainous southwest China, employing regression and path analysis models to assess relationships between environmental cognition, willingness to participate, and actual participation behavior. The research seeks to bridge the gap between awareness and action, identifying factors contributing to this discrepancy (

Figure 1). Our findings highlight the importance of enhancing environmental awareness and promoting active participation. By understanding and addressing these dynamics, we aim to mitigate environmental damage in rural areas through targeted interventions, ultimately fostering more effective environmental governance.

This study makes three main contributions. Firstly, it enriches social cognition and planned behavior theories by establishing path analysis and comparative analysis from awareness to willingness to action. This approach helps elucidate the fundamental reasons and mechanisms for potential discrepancies among these stages. Secondly, it introduces an index system for evaluating environmental cognition, participation willingness, and behavior, tailored to the production, life, and ecological contexts of rural areas. This index system, considering environmental functions and community impacts, aims to enhance current environmental governance methodologies. Lastly, the study uncovers a significant gap between environmental awareness, willingness, and actual participation levels, with behavior exceeding cognition and willingness, providing critical insights into understanding this paradox.

3. Study Area and Methodology

3.1. Study Area

The upper reaches of the Min River, located on the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau, form an essential ecological barrier for the Chengdu Plain and a critical water-conserving region for the upper Yangtze River. This area is ecologically fragile due to the intermingling of agricultural and pastoral zones. High altitude, steep terrain, and low temperatures create challenging natural conditions that hinder sustainable food production for the growing population. Consequently, agricultural expansion has led to severe soil erosion and impoverishment due to poor management practices. The region’s low annual rainfall and high evaporation result in frequent natural disasters, highlighting the urgent need for ecological management. This study focuses on Li County in the Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan Province, China. Covering an area of approximately 4323 km

2, Li County spans from latitudes 31°25′ N to 31°57′ N and longitudes 103°10′ E to 104°07′ E (

Figure 2). The county’s complex and diverse topography and climate, situated in the transition zone from the Sichuan Basin to the eastern Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, contribute to its rich natural resources and diverse ecosystems. Elevations range from 1100 m to 4500 m above sea level. Li County is predominantly rural, with a population of around 125,000, mainly comprising Tibetans and the Qiang ethnic minority. The local economy primarily relies on agriculture and livestock farming, with tourism playing a relatively minor role.

Li County is distinguished by its unique natural and socio-economic characteristics. The area benefits from a rich heritage of environmental conservation, rooted in the traditional knowledge of local ethnic communities. Despite its natural beauty and cultural importance, Li County faces environmental issues such as soil erosion and deforestation. These challenges threaten the sustainability of local livelihoods and ecosystems. Various environmental governance initiatives have been introduced recently to tackle these issues. Consequently, Li County serves as an ideal case to study the connections between environmental cognition, the willingness to participate in environmental governance, and actual participatory behavior among rural households.

3.2. Variable Measurement

3.2.1. Environment Cognition

We used a multidimensional perspective to construct an indicator system for environmental cognition through three perspectives: production, ecology, and living space. These perspectives were chosen because they constitute the three main fields of rural farmers’ daily life, and environmental behaviors in these fields influence each other [

50]. The goal of this study is to gather information from farmers regarding various aspects of sustainable farming practices.

For instance, in the living space, we seek to understand their opinions on the benefits of converting toilets for healthier living. By ‘healthier living,’ we refer to practices that enhance sanitation, personal hygiene, and overall health. This encompasses changes such as upgrading from pit latrines to modern sanitary toilets, which can reduce the spread of diseases and improve living conditions. In the ecological space, we want to know if farmers believe that mulch without proper recycling and disposal contributes to environmental pollution. Lastly, in the production space, we aim to gather insights on whether deforestation causes soil erosion and flooding. These specific questions, among others, are included in our survey, which will be provided in

Appendix A.

This approach not only expands the scope of environmental cognition but also helps farmers contemplate environmental issues genuinely and profoundly based on their own production and life experiences. For instance, we observed in our study that farmers who have experienced soil erosion or flooding disasters firsthand were more likely to acknowledge deforestation as a contributing factor to these issues. Similarly, those who noticed improvements in sanitation and personal health after toilet upgrades were more likely to perceive these changes as beneficial to a healthy lifestyle. Moreover, those who witnessed the pollution caused by non-recycled mulch were more inclined to recognize it as a contributing factor to environmental degradation.

The questions were evaluated on a five-point Likert scale, a widely adopted scale that can accurately gauge an individual’s perception level towards an issue [

51]. Our study aimed to develop an environmental knowledge measure for farmers that encompasses their understanding of production, ecology, and living space. To ensure the content validity of our scale, we referred to the construction method of the Chinese Environmental Knowledge Scale (CEKS) [

52,

53]. The ultimate goal of this measure is to gain a deeper understanding of farmers’ environmental participation behaviors and the potential factors that influence them.

3.2.2. Willingness to Participate in Environment

To explore farmers’ attitudes toward environmental governance, we created indicators to assess their willingness to participate in production, ecological, and living spaces. Understanding this willingness is crucial because environmental governance success often depends on farmers’ involvement [

54]. We asked participants about their willingness to join toilet conversion projects in the living space, reuse retrieved mulch in the ecological space, and report or stop indiscriminate logging in the production space. These questions were rated on a five-point Likert scale.

3.2.3. Environmental Participation Behavior

We established an index system to measure farmers’ actual participation in environmental governance across production, ecology, and living spaces. Recognizing that behavior often differs from stated willingness [

55], we used actual participation behavior indicators. For example, we asked farmers if they participated in toilet renovation (living space), recovered and reused mulch (ecological space), and complied with and participated in deforestation rectification (production space). These questions were also rated using the Likert scale.

3.2.4. Household Demographic Characteristics of Farm Households

This study examines the demographic characteristics of farm households and their impact on environmental participation behavior. We specifically looked at the highest education level of the farming population, the ethnicity of the household head, and the number of household members (household size). Historical data and studies show that an individual’s education level can enhance their knowledge of environmental issues and promote environmental behavior [

56]. Besides education level, other factors like household size and the ethnic background of individuals may also impact environmental behavior, as they influence decision-making processes and values.

3.2.5. Geographical Characteristics of Farm Households

In this study, we examined the geographical features of farm households. These features included elevation, distance from the county center, and the average area of arable land per family member. Understanding these variables is crucial for comprehending their impact on environmental participation behavior. Research indicates that a farm household’s access to environmental knowledge and resources may be influenced by factors such as elevation and proximity to the county center [

57]. Additionally, the availability of land resources may affect the willingness and ability of farm households to engage in environmental participation behaviors.

3.2.6. Socio-Economic Characteristics of Farm Households

We also examined the socioeconomic characteristics of farm households. These characteristics included occupational diversification, networks, income levels, participation in farmers’ cooperatives, household asset levels, and the presence of cadres among household members. Gender dynamics, an influential factor in environmental participation, were not extensively analyzed in this study but warrant attention for future research. These factors can impact farmers’ perceptions and willingness to engage in environmental participation behaviors. For instance, farmers’ financial ability to implement environmental behaviors might be influenced by their income level and assets. The involvement of family members in cadres and cooperatives can affect the household’s status and influence in the community, which in turn can impact their participation in environmental activities [

58].

3.2.7. Farmers’ Land Use Characteristics

In this study, we analyzed the land use characteristics of farm households. Factors such as abandoned land, land transfer, cultivation methods, and agricultural mechanization were considered. Our aim was to investigate how these factors affect farmers’ attitudes and behaviors towards environmental participation on their land. Research evidence indicates that land use practices can be influenced by farmers’ perceptions and practices of environmental protection [

59]. The level of agricultural mechanization, which can be associated with the socioeconomic status of farm households, can impact their environmental participation behavior. Greater mechanization may lead to a decline in land quality and an increase in environmental stress due to intensive farming practices.

3.3. Data Collection

The primary data collection was conducted over a 15-day period in mid-July 2021. Prior to commencing the primary data collection, a pilot survey was conducted to refine the questionnaire and ensure it was aligned with the research objectives. Notably, during this initial phase, two preliminary surveys were conducted, involving interviews with local residents and government leaders to understand their perception of environmental problems, alongside a thorough review of relevant literature. The insights gained from these preliminary surveys, including the feedback received and the comprehension of the local environmental problems, were instrumental in shaping the final questionnaire. The data collection employed a face-to-face interview approach. A team of interviewers, proficient in the local language, administered the questionnaires to ensure accurate communication and comprehension. Before each interview, participants were fully informed about the study’s purpose and provided written informed consent.

The survey was designed to cover various villages located in Li County, Sichuan Province, China. The selection of these villages was primarily based on the diversity of altitude (high, medium, and low), different income levels, and main types of livelihoods (tourism-oriented or agriculture-oriented), leveraging our prior research experience in the region. However, due to labor migration and unavailability of respondents in some households during the survey period, a substantial proportion of the surveyed villages were eventually selected based on a random sampling approach. This approach, while unplanned, offered the advantage of mitigating selection bias and potentially increasing the generalizability of the study’s findings. Approximately 30 responses were obtained during the pilot survey, each thoroughly analyzed to enhance the clarity, relevance, and comprehensibility of the questionnaire. The revised questionnaire, informed by the environmental problems identified in the preliminary survey and literature review, was then implemented during the primary field survey.

The data collection process was divided into two parts. Firstly, interviews were conducted with county and village officials to cover a wide range of topics, such as local environmental governance, industrial development, ecological safety, socio-economic conditions, and population growth. Secondly, a questionnaire-based survey was administered to farming households in the region. The questionnaire aimed to gather detailed information on various aspects such as family background, livelihood characteristics, resource endowment, environmental awareness, attitudes towards environmental governance, and the farmers’ actual participatory behavior. Each survey took around 90 min, and a total of 579 valid responses were collected.

The study utilized data gathered from a refined questionnaire as the empirical basis for investigating environmental cognition and participatory behavior in environmental governance among rural households in Li County. This approach provided a comprehensive and detailed understanding of the topic. Data from our refined questionnaire aligns with local Li County statistics: average education level is primary school and gender ratio among households is balanced at 1.03:1, reinforcing the representativeness of our findings.

3.4. Data Analysis

In this study, data analysis will be conducted using SPSS 25. The collected measurement data and questionnaire results will be subjected to statistical processing and analysis. Various statistical methods such as Pearson correlation analysis, stratum-by-stratum attribution analysis, and path analysis will be employed to explore the relationship between environmental perceptions, willingness to participate in the environment, and environmental participation behavior.

To gain insight into the relationship between farmers’ environmental perceptions, willingness to govern the environment, and their participation behavior, we conducted a Pearson correlation analysis. This analysis will reveal the direction and strength of the linear relationship between the variables, providing a preliminary understanding of the topic. We used hierarchical attribution analysis to explore the contribution of environmental perceptions and willingness to govern the environment to environmental participation behavior. This approach involves adding or removing explanatory variables from the model to gain a deeper understanding of how these variables influence changes in environmental participation behavior. We will utilize path analysis, a sophisticated statistical method, to investigate the direct and indirect relationships between individuals’ perceptions of the environment, their willingness to govern it, and their participation in environmental activities. Path analysis is an extension of multiple regression models that have been widely utilized in various fields, including social sciences, biology, and geography. It is an effective tool for exploring complex cognitive-behavioral pathways.

Path analysis is a comprehensive method that considers both subjective perceptions and objective measurement factors to understand the multivariate effects of environmental perceptions and engagement behaviors. This approach is advantageous as it accounts for direct and indirect effects between variables, revealing deeper levels of complexity and avoiding potential drawbacks of traditional linear models.

By employing various statistical methods, our aim is to obtain a thorough comprehension of the environmental participation patterns of farm households and establish its correlation with their environmental perceptions and willingness to govern the environment. This study will provide valuable insights to enhance the effectiveness of environmental governance policies and practices.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of Respondents

Our analysis of household demographics shows that the farming population’s characteristics align with the proportional data in the local statistical yearbook, indicating a representative sample. The highest education level among the farming population is primarily at the junior high school (33.8%) and elementary school levels (30.4%), with only about 10% having attained higher education at the specialist level and above. Most household heads are from Qiang (46%) and Tibetan (45.6%) ethnic groups, and typical family sizes range from 3 to 5 members.

In terms of land use, most farming households did not abandon or transfer their land, relying mainly on manual labor for farming (99%, 86%, and 61%, respectively). The socio-economic attributes analysis shows that most households lack professionals or membership in professional farmers’ cooperatives. However, a majority had internet access at home. The livelihoods of most farmers are diversified, with household incomes generally less than 50,000 Yuan ($7007.41) per year. The household asset index ranged from 0.4 to 0.7 (on a scale of 0–1). Therefore, a range of 0.4–0.7 indicates that the total value of most households’ assets falls between 40% and 70% of the maximum possible value.

Geographic resource analysis revealed that over 50% of farm households reside at altitudes of 2000 m or below. Additionally, 41.6% are situated 10–30 km from the county town, while about 30% live in remote mountainous areas more than 30 km away. Furthermore, 52.7% of farm households have a per capita arable land area of 500 m

2 or more. Data analysis showed that the selected indicators had skewness coefficients less than 3 and kurtosis coefficients less than 8, meeting the requirements for approximate normal distribution. Each indicator falls within the standard range, as shown in

Table 1.

4.2. Analysis of Cognitive, Willingness, and Behavioral Level Differences and Paradoxes

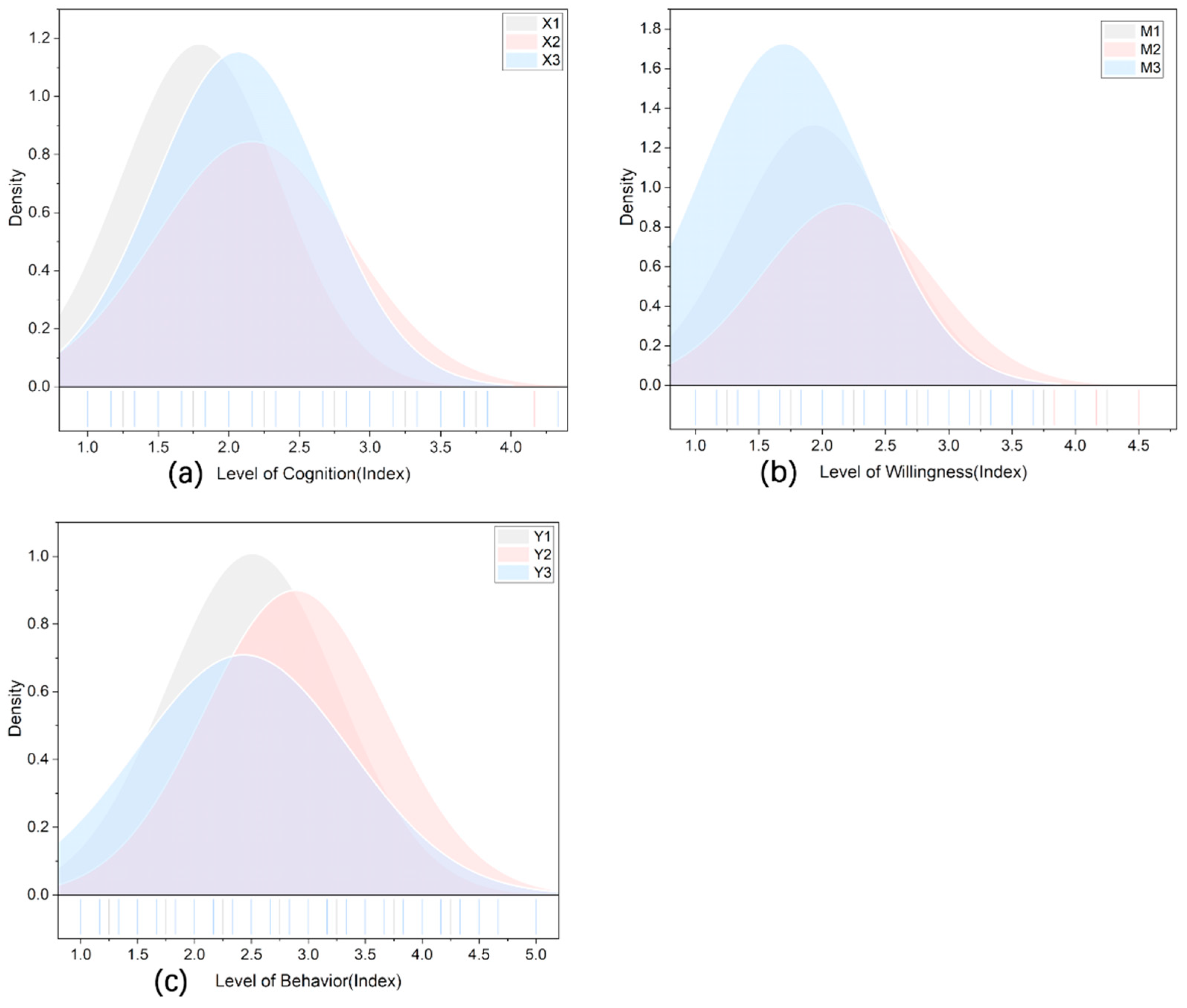

The study revealed significant differences in environmental cognition, willingness to participate in environmental activities, and actual environmental participation behavior (

Figure 3a–c). Environmental cognition was observed at a lower level, peaking between 1.5 and 2.5. Willingness to participate peaked at a slightly higher but still low level, between 1.75 and 2.25, showing a concentrated distribution. In contrast, environmental participation behavior was found at a mid-level, peaking between 2.5 and 3.0. Interestingly, our findings suggest that reported willingness to participate in environmental activities was lower than the actual behavior indicated. It is crucial to consider the potential influence of our data collection method on these findings. Factors like social desirability bias or discrepancies between self-reported and observed behavior might contribute to this discrepancy. We have taken steps to ensure the robustness of our data. The ensuing discussion will explore possible explanations for this observed trend.

4.3. Correlation Analysis

We utilized Pearson correlation analysis to examine the relationships between variables. Significant correlations were found between certain variables, as detailed in

Table 2. Specifically, cognitive level and willingness level were significantly correlated with behavioral variables. Additionally, mediating variables C01, W24, W26, W11, and W12 showed significant correlations with behavioral variables. These were included in the subsequent regression analysis.

4.4. Results of Stepwise Regression Analysis

- (1)

Regression results of environmental perception, willingness to participate in governance and environmental participation behavior

Stepwise regression analysis was conducted using X1-cognitive index and M1-willingness index for living space, X2-cognitive index and M2-willingness index for production space, and X3-cognitive index and M3-willingness index for ecological space as independent variables. The dependent variable was Y, representing overall spatial environment participation behavior. The final model included X2-cognitive index, M2-willingness index for production space, M1-willingness index for living space, and M3-willingness index for ecological space. The F test result (F = 57.536,

p = 0.000 < 0.05) confirmed the model’s effectiveness. No multicollinearity issues were detected, as all VIF values were below 5. The D-W value was close to 2, indicating no autocorrelation.

Table 3 shows that higher environmental cognition in the production space, as well as higher willingness to participate in environmental governance across production, living, and ecological spaces, are all associated with stronger environmental participation behavior.

In relation to our hypotheses, these results provide clear support for Hypothesis 3, demonstrating that willingness to participate (behavioral intention) is a strong and direct predictor of actual behavior across all three spatial contexts. They also offer partial support for Hypothesis 1, as environmental cognition was a significant predictor, but its influence was confined to the production space, underscoring the context-dependent nature of the cognition-behavior link.

- (2)

Regression results of mediating variables and environmental participation behavior

In this stepwise regression analysis (

Table 4), the independent variables were the highest education level of the farming population (C01), membership in a farmers’ cooperative (W24), family member cadre level (W26), elevation of the household (W11), and distance from the county town (W12). The dependent variable was the behavioral level of environmental governance participation. The model’s validity was confirmed by an F-test result of F = 14.395 and

p = 0.000 < 0.05. No multicollinearity issues were found, as all VIF values were below 5. The D-W value of around 2 indicated no autocorrelation. The study found that the distance from the county town had a significant negative impact on environmental participation behavior. In contrast, higher education levels, membership in farmer cooperatives, and family members in leadership positions had significant positive effects. Additionally, households at higher elevations demonstrated higher levels of participation in environmental governance.

These findings directly address the premise of Hypothesis 4, confirming that socio-economic and geographic factors—specifically education, cooperative membership, social status (cadre), elevation, and distance from urban centers—have significant direct effects on environmental participation behavior. This empirical evidence substantiates the claim that behavior is shaped by factors beyond cognition and willingness alone.

- (3)

Results of impact pathways of environmental participation behavior

Incorporating all relevant variables into the path analysis model (

Figure 4), we found that the highest education level among farming households does not have a direct association with environmental participation behavior in terms of household demographic attributes. However, it does have an indirect association. Specifically, higher education levels enhance cognition in living and ecological spaces, fostering a greater willingness to participate in environmental activities within these spaces. This increased willingness then influences the degree of environmental participation behavior. Essentially, higher education helps farmers better understand and assess environmental issues, encouraging active participation in environmental protection.

Regarding the geographic resource characteristics of households, the distance from the county town has a direct impact on environmental participation behavior. It also indirectly affects behavior through the perception of living space. Distance from the county town influences farmers’ access to environmental information and resources, thereby affecting their cognition of environmental issues and involvement in environmental behavior.

The impact of environmental cognition or willingness to participate in environmental initiatives on behavior is unclear concerning land use characteristics. Different land use methods might affect farmers’ environmental cognition and behavior in various ways. Conversely, the presence of family members as cadres or farmers’ membership in cooperatives can directly or indirectly impact environmental participation behavior through their perception of ecological space. For example, family members who are cadres or farmers in cooperatives may have increased status and influence in the community, enhancing their willingness and ability to participate in environmental activities.

The path analysis results provide a comprehensive picture regarding our hypotheses. They reinforce Hypotheses 2 and 3 by delineating the pathway through which education enhances cognition and, in turn, willingness, ultimately affecting behavior. Simultaneously, they elaborate on Hypothesis 4 by revealing the complex mediating roles of household attributes. Crucially, the model confirms that geographic distance exerts both a direct influence on behavior and an indirect one by shaping environmental perceptions, thereby offering a mechanistic explanation for the observed paradoxes between cognition, willingness, and action.

5. Discussion

5.1. Revisiting the Hypotheses: Linking Cognition, Willingness, and Action

Our findings present a complex picture regarding the relationships between environmental cognition, willingness, and action, offering both confirmation and important nuances to our initial hypotheses. In partial support of Hypothesis 1, which posited a positive correlation between environmental cognition and participation behavior, our results reveal that this relationship is highly context-dependent. The regression analysis (

Table 3) indicates that environmental cognition in the production space (X2) was a significant predictor of behavior, corroborating studies that emphasize the role of practical knowledge in driving actions tied to livelihoods [

60,

61]. However, cognition in living and ecological spaces did not emerge as direct significant predictors in the final model. This suggests that for rural residents, pragmatic knowledge related to income and survival (e.g., understanding the link between deforestation and soil erosion) is a more potent driver of behavior than more general environmental awareness, a nuance highlighted in other rural contexts [

20].

Hypotheses 2 and 3, which proposed a chain from environmental consciousness to willingness and then to behavior, received strong yet qualified support. The path analysis (

Figure 4) confirms that willingness (behavioral intention) in all three spaces—production (M2), living (M1), and ecological (M3)—was a powerful and direct driver of participation behavior, aligning strongly with the Theory of Planned Behavior [

62,

63]. However, the path from cognition to willingness was not always direct. Instead, as suggested in our model, factors like education level mediated this relationship, particularly enhancing cognition in living and ecological spaces, which in turn fostered willingness. This finding refines our initial model by showing that cognition does not automatically translate into willingness; its influence is often facilitated by other capacities.

Most significantly, our data strongly affirms Hypothesis 4 regarding the existence of practical paradoxes. The observed divergence—where actual behavior exceeded the levels predicted by cognition and willingness alone—is a central finding. This can be explained by the mechanisms outlined in H4. For instance, our analysis shows that geographic and demographic factors (e.g., distance from the county town, elevation, and family members being cadres) had significant direct and mediating effects (

Table 4,

Figure 4). Farmers living farther from town exhibited higher pro-environmental behavior, likely due to a greater direct dependence on local ecosystems for survival, a form of instrumental motivation that overrides stated intent [

64]. Similarly, the influence of family cadres points to the role of social norms and collective compliance, where behavior is influenced by social standing and policy pressure rather than personal cognition alone [

65].

5.2. Explaining the Divergence: Key Socio-Cultural Mechanisms

Our findings validate Hypothesis 4, confirming that the cognition–action gap is bridged by contextual factors beyond individual cognition. Our analysis reveals three primary pathways that explain why farmers’ actions surpass their stated cognition and willingness.

- (i)

The Role of Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Community Norms

First, pro-environmental behavior is often underpinned by traditional ecological knowledge and deeply ingrained community norms. In Li County, practices such as maintaining communal water sources and protecting village fengshui forests are frequently sustained not through formal environmental awareness, but through an unconscious adherence to inherited customs. These actions are embedded in a cultural framework where environmental stewardship is synonymous with community identity and social cohesion [

66]. This mechanism explains why farmers may engage in conservation behaviors that appear disconnected from their survey-based environmental cognition; their actions are driven by a cultural logic that operates independently of modern environmental discourse.

- (ii)

Collective Compliance Under Government Policy Pressure

Second, collective compliance in response to government policy pressure serves as a critical extrinsic motivator. Initiatives like the “Toilet Revolution” and reforestation campaigns are typically implemented through strong top-down promotion, creating a clear expectation for participation. In this context, farmers’ behavior can be understood as a pragmatic response to institutional power and potential incentives or sanctions, rather than a direct outcome of personal environmental intent. This form of collective action aligns individual behavior with state agendas, creating a compliance-based pathway to environmental participation that may exist irrespective of, or even contrary to, personal cognition [

67,

68].

- (iii)

Instrumental Motivations Rooted in Livelihood Security

Third, and perhaps most potently, instrumental motivations directly tied to livelihood security shape environmental actions. The most consistent pro-environmental behaviors observed were those with a clear, tangible link to economic well-being and risk reduction. Farmers readily adopted soil and water conservation practices when they perceived a direct benefit to crop yields or disaster mitigation. This practical, benefit–cost calculus—a form of instrumental rationality—often overrides stated attitudes, leading to a “behavior-first” pattern where action is divorced from formal environmental awareness. This mechanism is particularly strong in remote, land-dependent households, whose welfare is most directly tied to the health of the local ecosystem [

69].

These three mechanisms are not mutually exclusive; they often operate in tandem. A single action, such as participating in a reforestation campaign, might simultaneously be influenced by policy pressure (ii), the economic benefit of potential subsidies (iii), and a community norm of contributing to collective projects (i). The relative weight of each mechanism varies across different spatial contexts and governance initiatives, helping to explain the varying effectiveness of policies across production, living, and ecological spaces as shown in our results.

5.3. Policy Implications and Recommendations

Our findings carry significant implications for rural environmental governance. Moving beyond generic awareness-raising campaigns, policies must be strategically tailored to leverage the identified socio-cultural and economic mechanisms.

Integrate Traditional Knowledge with Formal Policy: Environmental programs should actively identify and incorporate relevant traditional ecological knowledge. Instead of imposing entirely external models, policies that build upon and legitimize existing community norms (e.g., formally recognizing and supporting traditional forest management practices) are likely to achieve higher legitimacy and sustained compliance.

Design Differentiated Incentive Structures: Recognizing the potency of instrumental motivations, policymakers should develop precise, context-sensitive incentive systems. For remote, land-dependent households, direct subsidies for proven conservation practices (e.g., sustainable soil management) may be most effective. For households with diversified incomes, support for linking eco-friendly products (e.g., organic produce) to premium markets could create powerful economic motivations.

Facilitate Community-Led Governance: Given the strength of social norms, governance models should shift from purely top-down implementation to facilitating community-led initiatives. Providing villages with the resources and technical support to design and manage their own environmental projects (e.g., small-scale waste management systems) can harness social pressure and collective identity for positive environmental outcomes, fostering a sense of ownership that transcends short-term policy cycles.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

While our study produced significant findings, there are limitations. The data were limited to farm households in the mountainous area of Li County, Sichuan, China, potentially restricting the generalizability of our results. Future studies should explore other regions or community types to validate and extend our findings. Our study focused on environmental behaviors without delving into their environmental impacts. Future research should explore the tangible effects of farmers’ practices on environmental quality and ecosystem services for a comprehensive understanding. Additionally, our quantitative methods did not delve into the sociocultural context influencing farmers’ behaviors. Future research could use qualitative methods like in-depth interviews and participant observation for deeper insights.

In conclusion, our study provides important insights into the factors influencing environmental behaviors among rural residents in Li County, highlighting their complexity. The observed discrepancy between environmental cognition, willingness, and actual behaviors suggests the presence of other unmeasured factors. Future research should explore these factors, including community pressure, cultural expectations, unconscious behavior patterns, and practical adaptation needs. Broader educational initiatives and awareness-raising efforts are essential, as residents may not perceive the studied issues as primarily environmental in nature.