Methodology for the Identification and Evaluation of the Tourism Potential of the Natural and Cultural Heritage Inventory

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Methodology

3.1. Geographical Location

3.2. Definition of Variables

3.3. Inventory Components

3.4. Evaluation of Tourist Attractions

3.4.1. Criteria for the Evaluation and Scoring of Cultural Heritage

3.4.2. Criteria for the Evaluation and Scoring of Natural Sites

3.5. Local Survey

3.6. Expert Panel and Scoring Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of Scores—Figure 4: Cultural Heritage

4.2. Analysis of Scores—Figure 5: Intangible Heritage and Groups of Special Interest

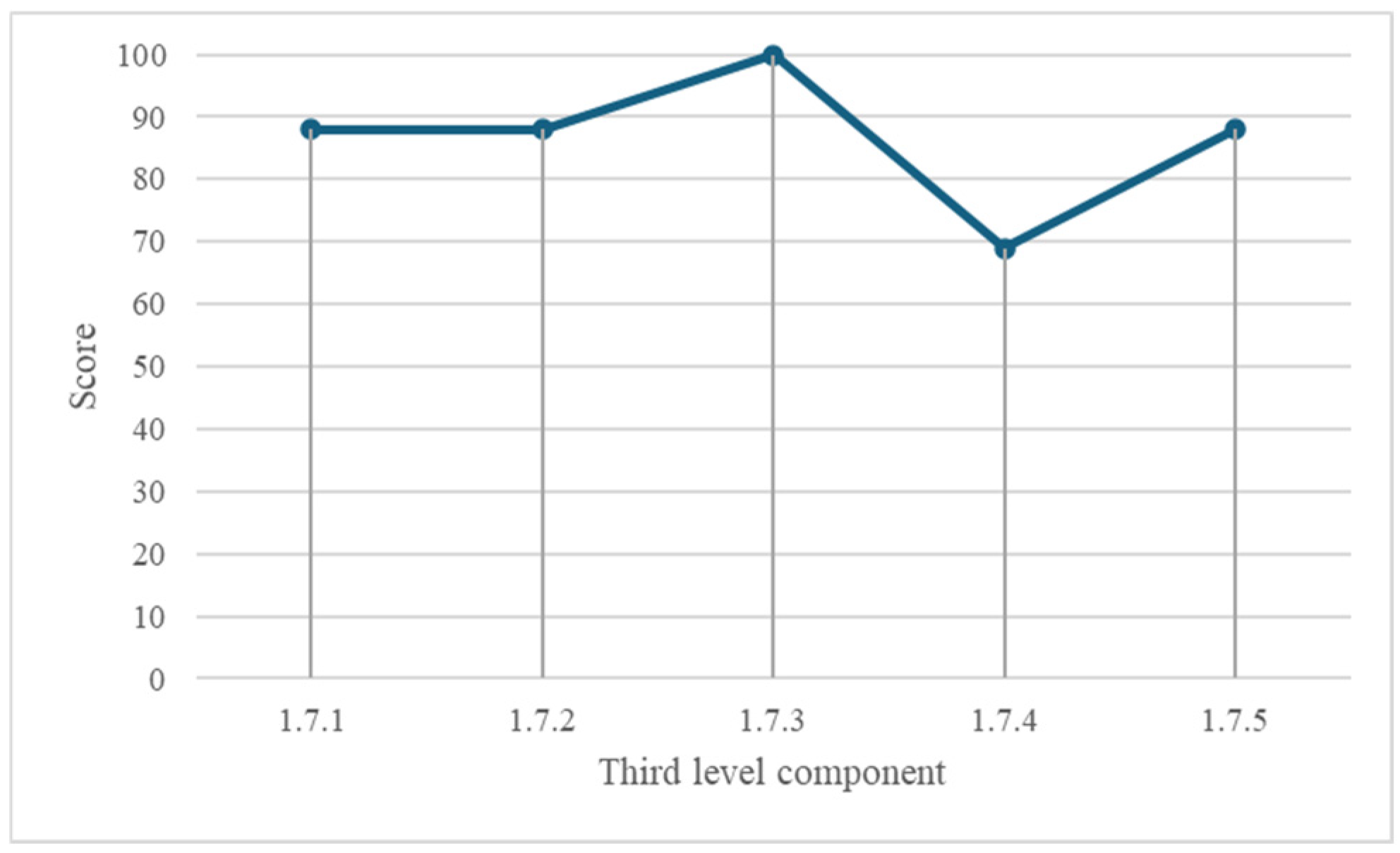

4.3. Analysis of Scores—Figure 6: Festivities and Events

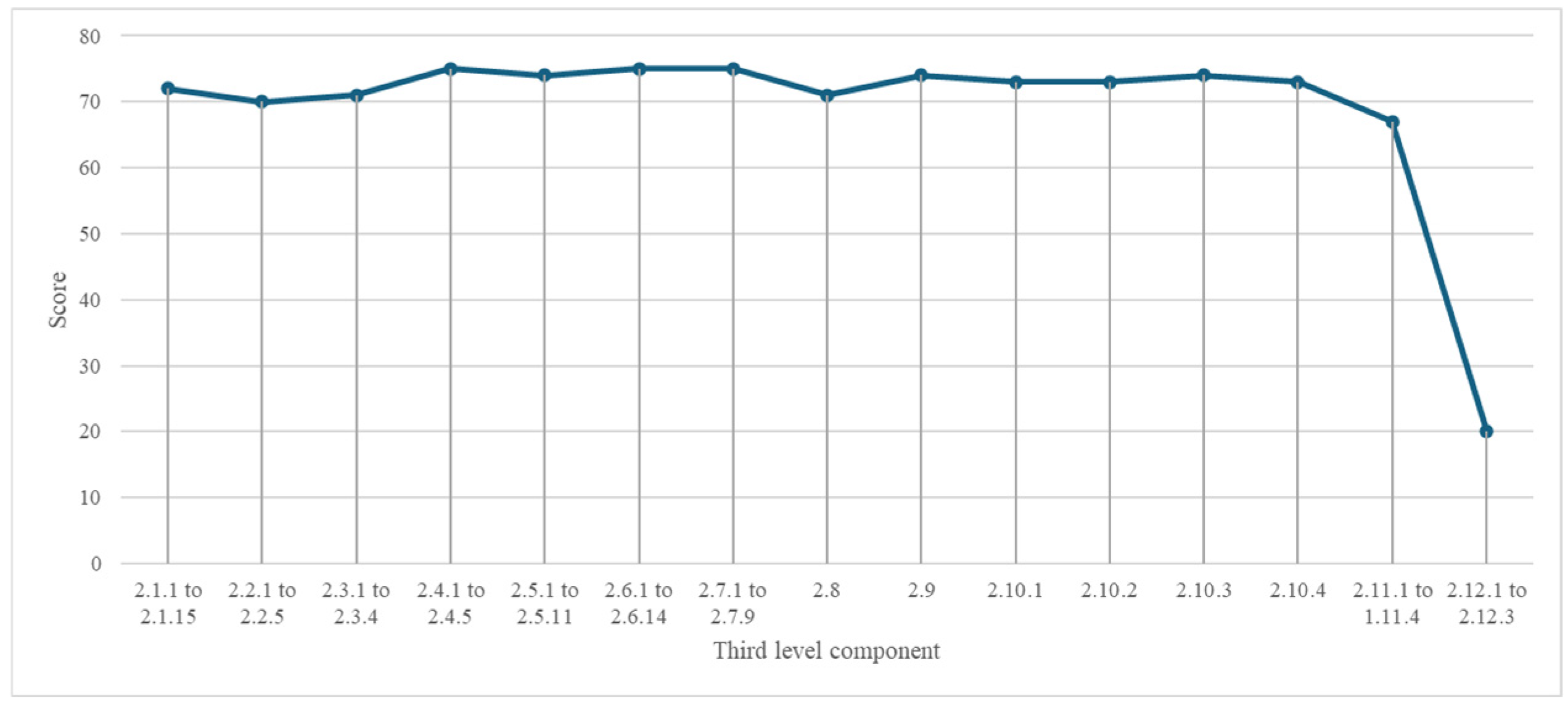

4.4. Analysis of Scores—Figure 7: Natural Sites

5. Discussions and Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions and Limitations

Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Inventory Components

Appendix A.2. Inventory Components

References

- Wąsowicz, M. Assessment of project success. Is sustainability is relevance? Transform. Bus. Econ. 2021, 20, 939. [Google Scholar]

- Streimikiene, D. Sustainability assessment of tourism destinations from the lens of green digital transformations. J. Tour. Serv. 2023, 14, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinler, M. Formulation of historic residential architecture as a background to urban conservation. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leno Cerro, R. Los recursos turísticos en un proceso de planificación: Inventario y evaluación. Pap. Tur. 1991, 7, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Camara, C.J.; Morcate Labrada, F.D.L.Á. Metodología para la identificación, clasificación y evaluación de los recursos territoriales turísticos del centro de ciudad de Fort-de-France. Arquit. Urban. 2014, 35, 48–67. [Google Scholar]

- Organización Mundial de Turismo. Evaluación de los Recursos Turísticos; Organización Mundial de Turismo: Madrid, Spain, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Leno Cerro, F. Técnicas de Evaluación del Potencial Turístico; Ministerio de Industria, Comercio y Turismo Dirección General de Política Turística: Madrid, Spain, 1993.

- Gunn, C.A. Tourism Planning, 2nd ed.; Taylor and Francis: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Boullon, R.C. Planificación del Espacio Turístico; Trillas: Mexico City, México, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- The Guardian. Mompós, Colombia, the Town That Time Forgot. 2012. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2012/sep/21/colombia-mompos-forgotten-town?utm_source (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- UNESCO. Historic Centre of Santa Cruz de Mompox. 2024. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/742 (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Silva, J. Planeamento de produtos turísticos. In Planeamento e Desenvolvimento Turístico; Silva, F., Umbelino, J., Eds.; Lidel—Edições Técnicas, Lda.: Lisboa, Portugal, 2017; pp. 197–219. [Google Scholar]

- Braga, J.L.; Borges, I.; Brás, S.; Mota, C.; Costa, F. Inventorying tourist resources: Assessment of the tourist potential of Vieira do Minho. Int. Conf. Tour. Res. 2023, 6, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bote, V. Planificación Económica del Turismo; Trillas: Mexico City, México, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, K.; Clarke, J. The Tourism Development Handbook; Continuum International Publishing Group: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cartuche, D.; Romero, J.; Romero, Y. Evaluación multicriterio de los recursos turísticos en la Parroquia Uzhcurrumi, Canton Pasaje, Provincia de El Oro. Rev. Interam. Ambiente Tur. 2018, 14, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zamorano, F. Turismo Alternativo. Servicios Turísticos Diferenciados; Trillas: Mexico City, México, 2002. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- SECTUR. Planeación y Gestión del Desarrollo Turístico; SECTUR: Mexico City, México, 2004. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Petrović, D.; Vukoičić, D.; Milinčić, M.; Ristić, D. Tourism potential assessment model of the monasteries of the Ibar cultural tourism zone. J. Environ. Tour. Anal. 2020, 8, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matshusa, K.; Thomas, P.; Leonard, L. A methodology for examining geotourism potential at the Kruger National Park, South Africa. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2021, 34, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boc, E.; Filimon, A.L.; Mancia, M.-S.; Mancia, C.A.; Josan, I.; Herman, M.L.; Filimon, A.C.; Herman, G.V. Tourism and cultural heritage in Beiuș Land, Romania. Heritage 2022, 5, 1734–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos Gutiérrez, Y.; Cadena Íñiguez, J.; Almeraya Quintero, S.X.; Ramírez López, A.; Figueroa Sandoval, B. Inventory of heritage resources and interior routes with potential touristic in Pinos, Zacatecas. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agrícolas 2019, 10, 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.P. A study on Kinmen Residents’ perception of tourism development and cultural heritage impact. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2016, 12, 2909–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Comercio Industria y Turismo. Metodología para la Elaboración del Inventario de Atractivos Turísticos; Grupo de Planificación y Desarrollo Sostenible del Turismo Bogotá: Bogotá, Colombia, 2020.

- Levin, J. Elementary Statistics in Social Research; Pearson Education India: Noida, India, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Azmi, F.A.M.; Ismail, S.; Rahman, R.A.; Sabit, M.T.; Mohammad, J. A sustainable model for heritage property: An integrative conceptual framework. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.; Zheng, Z.; Tian, D.; Zhang, R.; Law, R.; Zhang, M. Resident-tourist value co-creation in the intangible cultural heritage tourism context: The role of residents’ perception of tourism development and emotional solidarity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiridon-Ursu, P.; Breaban, I.G.; Sandu, I.; Ursu, A. A GIS-based model for multicriteria assessment of architectural cultural heritage conservation status. Present Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 18, 225–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO; WTO; OECD. Aid for Trade and Value Chains in Tourism. 2013. Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/devel_e/a4t_e/global_review13prog_e/tourism_28june.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Robayo-Acuña, P.V.; Chams-Anturi, O. Open innovation in hospitality and tourism services: A bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2025, 17, 394–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lurdes Calisto, M.; Costa, T.; Alves Afonso, V.; Rosa Nunes, C.; Umbelino, J. Local governance and entrepreneurship in tourism–a comparative analysis of two tourist destinations. J. Tour. Serv. 2023, 14, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, K.; Stefaniec, A.; Hosseini, S. World heritage sites in developing countries: Assessing impacts and handling complexities toward sustainable tourism. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chams-Anturi, O.; Moreno-Luzon, M.D.; Escorcia-Caballero, J.P. Linking organizational trust and performance through ambidexterity. Pers. Rev. 2020, 49, 956–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification | Score | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Tangible Heritage | ||

| State of conservation: Assesses whether the attraction has retained its aesthetic appearance and physical integrity since its origin, or through human interventions such as restoration aimed at enhancing its quality. | 21 | 70 points |

| Constitution of the asset: Considers the materials and techniques used in its creation. Older assets built with outdated or rare methods deserve recognition; however, those using modern techniques may also be valued for their uniqueness or technological innovation. | 21 | |

| Representativeness: Reflects the asset’s significance as a key element in historical, social, or cultural events. | 28 | |

| Intangible Heritage | ||

| Collective: Belongs to a group of people who identify with, use, and transmit the practice or tradition. | 14 | 70 points |

| Traditional: Passed down from generation to generation, often with origins so ancient they are difficult to trace. | 14 | |

| Anonymous: Has no known author and dates back to remote historical periods. | 14 | |

| Spontaneous: Transmitted naturally, simply, and genuinely. | 14 | |

| Popular: Reflects the everyday life of the general population. | 14 | |

| Festivities and Events | ||

| Event organization: Evaluates the quality of the event’s organization, considering aspects such as content, scheduling, compliance, and logistical execution. | 30 | 70 points |

| Socio-cultural benefits for the community: Measures the event’s impact on the community, including its connection with regional folklore, promotion of the region, and the degree of community involvement. | 20 | |

| Local economic benefits: Analyzes increases in regional income, improvements in quality of life, and the efficient use of the budget allocated to the event. | 20 | |

| Groups of Special Interest | ||

| Respect for traditions: Reflects the authentic preservation of cultural heritage through adherence to traditional customs. | 70 | 70 points |

| Classification | Score | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Local: Degree of recognition of the attraction within the municipal area. | 6 | 30 points |

| Regional: Degree of recognition of the attraction within one or more departments. | 12 | |

| National: Degree of recognition of the attraction throughout the country. | 18 | |

| International: Degree of recognition of the attraction in two or more countries. | 30 |

| Classification | Score |

|---|---|

| Absence of air pollution: Refers to the lack of smog, which typically originates from vehicles and oil plants and can cause damage to vegetation and result in agricultural losses. | 10 |

| Absence of water pollution: Occurs when water bodies are not affected by chemicals, fuel spills, or fertilizer runoff from agricultural areas, as well as domestic detergents and soaps that harm aquatic life. | 10 |

| Absence of visual pollution: Related to inappropriate architecture, visual obstructions, and the presence of waste. | 10 |

| Absence of noise pollution: Refers to noise levels that do not interfere with the enjoyment of nature. | 10 |

| State of conservation: Describes the condition of local flora and fauna, including signs of erosion or subsistence-level extractive activities. | 10 |

| Diversity: Refers to the variety of species (both flora and fauna), habitats, landscapes, and sensory elements such as natural scents and scenic views. | 10 |

| Uniqueness: Covers exceptional or unique characteristics, including endemism (species found only in a specific area) or the rarity of landscapes with distinctive features in a particular environment. | 10 |

| Total | 70 points |

| Expert | Academic Background | Professional Experience | Area of Expertise | Selection Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | MSc in Heritage Management and Cultural Tourism | 8 years working in conservation projects in the Caribbean region | Architectural heritage, urban inventories | Experience with heritage inventories and UNESCO guidelines |

| E2 | MSc in Tourism Planning and Management | 10 years in environmental impact assessment and ecotourism planning | Natural sites, biodiversity conservation | Field experience in ecosystems of the Magdalena River |

| E3 | PhD in Tourism | 9 years in tourism development, community-based tourism, and destination management | Tourism planning, rural tourism | Participation in regional tourism plans |

| Tangible Cultural Heritage (Groups 1.1 to 1.5) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Quality (Max. 70 Points) | Significance (Max. 30 Points) | Total | |||||||

| State of Conservation | Asset Constitution | Representativeness | Total | Local | Regional | National | International | Total | ||

| 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 1.1 | 18 | 19 | 28 | 65 | 6 | 6 | 71 | |||

| 1.1 | 21 | 21 | 28 | 70 | 12 | 12 | 82 | |||

| 1.1 | 21 | 21 | 24 | 66 | 12 | 12 | 78 | |||

| 1.1 | 19 | 20 | 20 | 59 | 6 | 6 | 65 | |||

| 1.2 | 21 | 21 | 28 | 70 | 6 | 6 | 76 | |||

| 1.3 | 21 | 21 | 28 | 70 | 12 | 12 | 82 | |||

| 1.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 1.5 | 21 | 21 | 28 | 70 | 12 | 12 | 82 | |||

| 1.5 | 20 | 20 | 16 | 56 | 6 | 6 | 62 | |||

| 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Intangible Cultural Heritage (Group 1.6) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Quality (Max. 70 Points) | Significance (Max. 30 Points) | Total | |||||||||

| Collective | Traditional | Anonymous | Spontaneous | Popular | Total | Local | Regional | National | International | Total | ||

| 1.6 | 14 | 14 | 8 | 14 | 14 | 64 | 12 | 12 | 76 | |||

| Festivals and Events (Group 1.7) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Quality (Max. 70 Points) | Significance (Max. 30 Points) | Total | |||||||

| Event Organization | Sociocultural Benefits for the Community | Local Economic Benefits | Total | Local | Regional | National | International | Total | ||

| 1.7 | 30 | 20 | 20 | 70 | 18 | 18 | 88 | |||

| 1.7 | 30 | 20 | 20 | 70 | 18 | 18 | 88 | |||

| 1.7 | 30 | 20 | 20 | 70 | 30 | 30 | 100 | |||

| 1.7 | 28 | 17 | 12 | 57 | 12 | 12 | 69 | |||

| 1.7 | 30 | 20 | 20 | 70 | 18 | 18 | 88 | |||

| Groups of Special Interest (Group 1.8) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Quality (Max. 70 Points) | Significance (Max. 30 Points) | Total | |||||

| Respect for Traditions | Total | Local | Regional | National | International | Total | ||

| 1.8 | 70 | 70 | 12 | 12 | 82 | |||

| Natural Sites (Groups 2.1 to 2.12) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Quality (Max. 70 Points) | Significance (Max. 30 Points) | Total | |||||||||||

| No Air Pollution | No Water Pollution | No Visual Pollution | No Noise Pollution | Conservation Status | Diversity | Uniqueness | Total | Local | Regional | National | International | Total | ||

| 2.1 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 5 | 60 | 12 | 12 | 72 | |||

| 2.2 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 3 | 58 | 12 | 12 | 70 | |||

| 2.3 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 5 | 59 | 12 | 12 | 71 | |||

| 2.4 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 63 | 12 | 12 | 75 | |||

| 2.5 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 7 | 62 | 12 | 12 | 74 | |||

| 2.6 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 63 | 12 | 12 | 75 | |||

| 2.7 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 63 | 12 | 12 | 75 | |||

| 2.8 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 59 | 12 | 12 | 71 | |||

| 2.9 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 62 | 12 | 12 | 74 | |||

| 2.10 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 61 | 12 | 12 | 73 | |||

| 2.10 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 61 | 12 | 12 | 73 | |||

| 2.10 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 62 | 12 | 12 | 74 | |||

| 2.10 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 61 | 12 | 12 | 73 | |||

| 2.11 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 8 | 3 | 55 | 12 | 12 | 67 | |||

| 2.12 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 20 | |||

| Rank | Resource/Category | Score | Recommended Development Direction |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Artistic and cultural events (International jazz festival, dance and music groups) | 100 | Develop an annual cultural program; strengthen crowd management strategies; design premium cultural tourism packages. |

| 2 | Festivals, fairs, exhibitions (Filigree fair, festival del dulce) | 88 | Create gastronomic and artisan circuits; formalize capacity and attendance control for events; improve temporary infrastructure for peak season. |

| 3 | Religious architecture (churches, convents, parish complexes) | 82 | Develop heritage interpretation routes; improve signage; regulate carrying capacity within small temples. |

| 4 | Craftsmanship and technical heritage (filigree workshops, artisanal construction techniques) | 82 | Promote experiential craft workshops; certify authentic filigree; support microenterprises in public spaces. |

| 5 | Museum collections and sacred art (Museum of religious art) | 82 | Create curated themed tours; improve the conditions of conservation exhibits; incorporate digital interpretation tools. |

| 6 | Groups of special interest (Indigenous, Afro-Colombian, Raizal, Rom, artisans, fishing communities) | 82 | Develop community-based tourism products; ensure participatory benefit-sharing models; train hosts and guides. |

| 7 | Urban/rural sectors and public space (historic center, Alameda) | 76 | Improve lighting and signage in public spaces; implement riverside viewpoints. |

| 8 | Intangible heritage expressions (gastronomy, music, rituals, traditional medicine) | 76 | Design culinary routes; promote traditional music and dance experiences; incorporate local narratives into guided tours. |

| 9 | High-value natural sites (lotic waters, flora-fauna observation zones, protected wetlands) | 73–74 | Develop ecological nature trails; improve signage and safety features. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chams-Anturi, O.; Paipa-Sanabria, E.; Escorcia-Caballero, J.P. Methodology for the Identification and Evaluation of the Tourism Potential of the Natural and Cultural Heritage Inventory. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11311. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411311

Chams-Anturi O, Paipa-Sanabria E, Escorcia-Caballero JP. Methodology for the Identification and Evaluation of the Tourism Potential of the Natural and Cultural Heritage Inventory. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11311. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411311

Chicago/Turabian StyleChams-Anturi, Odette, Edwin Paipa-Sanabria, and Juan P. Escorcia-Caballero. 2025. "Methodology for the Identification and Evaluation of the Tourism Potential of the Natural and Cultural Heritage Inventory" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11311. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411311

APA StyleChams-Anturi, O., Paipa-Sanabria, E., & Escorcia-Caballero, J. P. (2025). Methodology for the Identification and Evaluation of the Tourism Potential of the Natural and Cultural Heritage Inventory. Sustainability, 17(24), 11311. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411311