Solar-Powered RO–Hydroponic Net House: A Scalable Model for Water-Efficient Tomato Production in Arid Regions

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Insect-proof net houses that provide natural ventilation and reduce pest pressure, minimizing the need for chemical control and energy-intensive cooling.

- Closed hydroponic systems that recycle nutrient solutions, reducing water and fertilizer losses.

- Root zone cooling (RZC) technology that maintains optimal root temperatures and enhances plant physiological performance under high ambient heat.

- Cost-effective solar-powered systems—a 100% off-grid setup for irrigation and an AC/DC hybrid solar energy system for root zone cooling—ensuring reliable, renewable power with minimal operational costs.

- Ultra-low energy drippers (ULEDs) that deliver precise irrigation at extremely low pressure, maximizing water-use efficiency.

2. Materials and Methods

- The study was carried out in a solar-powered closed hydroponic system established inside an insect-proof net house. The production system integrated several innovative technologies:

- Net house: A steel-frame structure covered with insect-proof netting to reduce pest infestation and facilitate natural ventilation.

- Hydroponic system: Closed soilless cultivation using perlite substrate in polystyrene pots. Nutrient solution was delivered through drip irrigation with ultra-low-pressure emitters, and drainage water was fully recirculated.

- Root zone cooling: A hybrid AC/DC cooling unit (1.5-ton ≈ 5.3 kW) maintained nutrient-solution temperature at 22–24 °C with ±1 °C precision. It operated through a battery-less hybrid PV-grid system using a 1.4 kW inverter and a 1.5 kWp PV array, with solar energy supplying ~75–80% of the cooling load. The inverter provided automatic grid support when needed, and tank-mounted sensors regulated compressor load for stable daytime cooling.

- A 25 × 4.5-inch yarn sediment cartridge fitted in a 20-inch housing with a 1-inch brass connection

- A 10-inch polyphosphate filter to inhibit scaling and extend membrane life.

- A multistage filtration includes 10-inch Yarn sediment, powder carbon, and block carbon.

- Seedling stage (Weeks 1–3): 1.5 dS/m.

- Vegetative stage (Weeks 4–8): 2.0 dS/m.

- Flowering stage (Weeks 9–13): 2.3 dS/m.

- Fruiting stage (weeks 14 onward): 2.5–3.5 dS/m.

- Yield: The fruits were harvested, weighed, and expressed as kg/plot, kg/plant, and kg/m2 of harvested area. Marketable yield (free of cracks, blossom end rot, or pest damage) and total yield were recorded separately. Fruit marketability followed quantitative thresholds: cracks > 5 mm in length, blossom-end rot lesions > 10 mm, sunscald covering > 10% of fruit surface, or any visible pest damage resulted in classification as unmarketable.

- Water use: The total irrigation volume for the net house was measured using inline digital flow meters (±2% accuracy) installed on the main supply line and calibrated monthly to ensure reliable readings. These measurements captured all water delivered to the system, and water-use efficiency for each variety was calculated by dividing the total recorded volume by the number of plots.

- Water-use efficiency (WUE): Calculated as the ratio of total marketable yield (kg) to total irrigation water applied (m3).

3. Results

3.1. RO Water and Low PH of Irrigation Water

3.2. Tomato Yield

3.3. Percentage of Marketable Fruits

- Early harvests (H1–H3, 2 to 12 March): Consistently high marketability (>85–90%), reflecting optimal fruit quality.

- Mid-season harvests (H4–H7, 12 March to 2 April): Moderate decline to about 60–70%, coinciding with reduced plant vigor and increasing fruit defects.

- Late harvests (H8–H12, 7 to 28 April): Sharp reduction to 15–30% due to fruit cracking, blossom-end rot, pest damage, and physiological aging.

3.4. Tomato Water and Fertilizer-Use Efficiency

3.5. Estimated Cost of Irrigation Water Using RO

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mordor Intelligence. UAE Tomato Market Size & Share Analysis—Growth Trends and Forecast (2025–2030). 2025. Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/uae-tomato-market (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- ICARDA. The Agricultural Sector in Qatar: Challenges and Opportunities; ICARDA: Aleppo, Syria, 2010; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11766/67649 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Mostafa, A.T. Potential of protected agriculture and hydroponics for improving the productivity and quality of high-value cash crops in qatar. In The Agricultural Sector in Qatar: Challenges and Opportunities; ICARDA: Aleppo, Syria, 2010; p. 452. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khateeb, S.A.; Zeineldin, F.I.; Elmulthum, N.A.; Al-Barrak, K.M.; Sattar, M.N.; Mohammad, T.A.; Mohmand, A.S. Assessment of Water Productivity and Economic Viability of Greenhouse-Grown Tomatoes under Soilless and Soil-Based Cultivations. Water 2024, 16, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaho, M.S.; Al-Mazidi, K. Evaluation of Selected Tomato Cultivars in Soilless Culture in Kuwait. Acta Hortic. 2005, 691, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICARDA. ICARDA-APRP Annual Report 2011–2012; ICARDA: Aleppo, Syria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Ortega, W.M.; Martínez, V.; Nieves, M.; Simón, I.; Lidón, V.; Fernandez-Zapata, J.C.; Martinez-Nicolas, J.J.; Cámara-Zapata, J.M.; García-Sánchez, F. Agricultural and Physiological Responses of Tomato Plants Grown in Different Soilless Culture Systems with Saline Water under Greenhouse Conditions. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-del Castillo, F.; Moreno-Pérez, E.d.C.; Pineda-Pineda, J.; Aragón-Ramírez, L.A. Nutrient dynamics and yield of tomato with different fertilizer sources and nutrient solution concentrations. Rev. Chapingo Ser. Hortic. 2025, 31, e2023.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, F.B.; Martinez, H.E.P.; da Silva, D.J.H.; Milagres, C.D.C.; Barbosa, J.G. Yield and quality of tomato grown in a hydroponic system, with different planting densities and number of bunches per plant. Pesqui. Agropecu. Trop. 2018, 48, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejatian, A.; Niane, A.A.; Nangia, V.; Al Ahmadi, A.H.; Naqbi, T.S.A.M.; Ibrahim, H.Y.H.; Al Dhanhani, M.A.H. Enhancing Controlled Environment Agriculture in Desert Ecosystems with AC/DC Hybrid Solar Technology. Int. J. Energy Prod. Manag. 2023, 8, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, A.T.; Al-Shankiti, A.; Nejatian, A. Potential of protected agriculture to enhance water and food security in the Arabian Peninsula. In Meeting the Challenge of Sustainable Development in Drylands Under Changing Climate—Moving from Global to Local, Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Development of Drylands, Cairo, Egypt, 12–15 December 2010; El-Beltagy, A., Saxena, M.C., Eds.; International Dryland Development Commission (IDDC): Cairo, Egypt, 2010; pp. 377–383. Available online: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/20163289046 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Fatnassi, H.; Zaaboul, R.; Elbattay, A.; Molina-Aiz, F.D.; Valera, D.L. Protected agriculture systems in the UAE: Challenges and opportunities. Acta Hortic. 2023, 1377, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirich, A.; Choukr-Allah, R. Water and Energy Use Efficiency of Greenhouse and Net house Under Desert Conditions of UAE: Agronomic and Economic Analysis. In Water Resources in Arid Areas: The Way Forward; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 481–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejatian, A.; Al Rawahy, M.; Niane, A.A.; Al Ahmadi, A.H.; Nangia, V.; Dhehibi, B. Renewable Energy and Net House Integration for Sustainable Cucumber Crop Production in the Arabian Peninsula: Extending Growing Seasons and Reducing Resource Use. J. Sustain. Res. 2024, 6, e240038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamad, T.; Parvez, M.; Lal, S.; Khan, O.; Yahya, Z.; Saeed Azad, A. Assessing Water Desalination in the United Arab Emirates: An Overview. In Proceedings of the 2023 10th IEEE Uttar Pradesh Section International Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Computer Engineering (UPCON), Gautam Buddha Nagar, India, 1–3 December 2023; pp. 1373–1377. [Google Scholar]

- Bdour, M.; Dalala, Z.; Al-Addous, M.; Kharabsheh, A.A.A.; Al-Khzouz, H. Mapping RO-Water Desalination System Powered by Standalone PV System for the Optimum Pressure and Energy Saving. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.E.; Hashaikeh, R.; Hilal, N. Solar Powered Desalination—Technology, Energy and Future Outlook. Desalination 2019, 453, 54–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsarayreh, A.A.; Al-Obaidi, M.A.; Ruiz-García, A.; Patel, R.; Mujtaba, I.M. Thermodynamic Limitations and Exergy Analysis of Brackish Water Reverse Osmosis Desalination Process. Membranes 2021, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raninga, M.; Mudgal, A.; Patel, V.; Patel, J. Advanced Exergy Analysis of Cascade Rankine Cycle-Driven Reverse Osmosis System. Energy Technol. 2024, 12, 2301062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, N. Fertilizer and Water Quality Management for Hydroponic Crops. 2019. Available online: https://hos.ifas.ufl.edu/media/hosifasufledu/documents/pdf/in-service-training/ist31188/IST31188---8.pdf? (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Singh, H.; Bruce, D. Electrical Conductivity and pH Guide for Hydroponics. 2016. Available online: https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/print-publications/hla/electrical-conductivity-and-ph-guide-for-hydroponics-hla-6722.pdf? (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Saskatchewan. Water Quality in Greenhouses. 2024. Available online: https://www.saskatchewan.ca/business/agriculture-natural-resources-and-industry/agribusiness-farmers-and-ranchers/crops-and-irrigation/horticultural-crops/greenhouses/water-quality-in-greenhouses? (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- University of Georgia. Testing the Water. In Horticulture Physiology; University of Georgia: Athens, GA, USA, 2012; Available online: https://hortphys.uga.edu/research/fertilization-in-greenhouses-an-introduction/testing-the-water/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Sánchez, E.; Di Gioia, F.; Ford, T.; Berghage, R.; Flax, N. Hydroponics Systems: Nutrient Solution Programs and Recipes; PennState Extension: University Park, PA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://extension.psu.edu/hydroponics-systems-nutrient-solution-programs-and-recipes (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Robbins, J.A. Irrigation Water for Grenhouses and Nurseries. 2018. Available online: https://www.uaex.uada.edu/publications/pdf/FSA-6061.pdf? (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Doreen. How Do I Treat My Water Source? In Plant-Prod: High Productivity Plant Nutrition; Doreen: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.plantprod.com/news/water-quality/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Sambo, P.; Nicoletto, C.; Giro, A.; Pii, Y.; Valentinuzzi, F.; Mimmo, T.; Lugli, P.; Orzes, G.; Mazzetto, F.; Astolfi, S.; et al. Hydroponic Solutions for Soilless Production Systems: Issues and Opportunities in a Smart Agriculture Perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Kleiner, Y.; Clark, S.M.; Raghavan, V.; Tartakovsky, B. Review of current hydroponic food production practices and the potential role of bioelectrochemical systems. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 2024, 23, 897–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelayo Lind, O.; Hultberg, M.; Bergstrand, K.-J.; Larsson-Jönsson, H.; Caspersen, S.; Asp, H. Biogas Digestate in Vegetable Hydroponic Production: pH Dynamics and pH Management by Controlled Nitrification. Waste Biomass Valorization 2021, 12, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, W.; Zhong, L.; Ji, F.; He, D. Bicarbonate used as a buffer for controling nutrient solution pH value during the growth of hydroponic lettuce. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2024, 17, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Spanish Association of Desalination and Reuse (AEDyR). Ten Facts About Water Desalination; The Spanish Association of Desalination and Reuse: Madrid, Spain, 2024; Available online: https://smartwatermagazine.com/news/smart-water-magazine/ten-facts-about-water-desalination? (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Dubai Electricity & Water Authority (DEWA). Slab Tariff. 2025. Available online: https://www.dewa.gov.ae/en/consumer/billing/slab-tariff (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Conti, V.; Mareri, L.; Faleri, C.; Nepi, M.; Romi, M.; Cai, G.; Cantini, C. Drought Stress Affects the Response of Italian Local Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Varieties in a Genotype-Dependent Manner. Plants 2019, 8, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesfay, T.; Berhane, A.; Gebremariam, M. Optimizing Irrigation Water and Nitrogen Fertilizer Levels for Tomato Production. Open Agric. J. 2019, 13, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casals, J.; Martí, M.; Rull, A.; Pons, C. Sustainable Transfer of Tomato Landraces to Modern Cropping Systems: The Effects of Environmental Conditions and Management Practices on Long-Shelf-Life Tomatoes. Agronomy 2021, 11, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntanasi, T.; Karavidas, I.; Zioviris, G.; Ziogas, I.; Karaolani, M.; Fortis, D.; Conesa, M.À.; Schubert, A.; Savvas, D.; Ntatsi, G. Assessment of Growth, Yield, and Nutrient Uptake of Mediterranean Tomato Landraces in Response to Salinity Stress. Plants 2023, 12, 3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghnimi, S.; Nikkhah, A.; Dewulf, J.; Van Haute, S. Life cycle assessment and energy comparison of aseptic ohmic heating and appertization of chopped tomatoes with juice. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuncoro, C.B.D.; Asyikin, M.B.Z.; Amaris, A. Development of an Automation System for Nutrient Film Technique Hydroponic Environment. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Seminar of Science and Applied Technology (ISSAT 2021), Online, 12 October 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficiciyan, A.; Loos, J.; Tscharntke, T. Similar Yield Benefits of Hybrid, Conventional, and Organic Tomato and Sweet Pepper Varieties Under Well-Watered and Drought-Stressed Conditions. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 628537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercolano, M.R.; Donato, A.D.; Sanseverino, W.; Barbella, M.M.; Natale, A.D.; Frusciante, L. Complex Migration History Is Revealed by Genetic Diversity of Tomato Samples Collected in Italy During the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galmés, J.; Ochogavía, J.M.; Gago, J.; Roldán, E.J.; Cifré, J.; Conesa, M.À. Leaf Responses to Drought Stress in Mediterranean Accessions of Solanum lycopersicum: Anatomical Adaptations in Relation to Gas Exchange Parameters. Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 36, 920–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebisch, F.; Max, J.F.J.; Heine, G.; Horst, W.J. Blossom-end rot and fruit cracking of tomato grown in net-covered greenhouses in Central Thailand can partly be corrected by calcium and boron sprays. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2009, 172, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinh, T.D.; Yoshida, Y.; Ooyama, M.; Goto, T.; Yasuba, K.; Tanaka, Y. Comparative Analysis on Blossom-end Rot Incidence in Two Tomato Cultivars in Relation to Calcium Nutrition and Fruit Growth. Hortic. J. 2018, 87, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, P.; Ho, L.C. Uptake and Distribution Ofnutrients in Relation to Tomato Fruit Quality. Acta Hortic. 1995, 412, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Teruel, M.Á.; Molina-Aiz, F.D.; López-Martínez, A.; Marín-Membrive, P.; Peña-Fernández, A.; Valera-Martínez, D.L. The Influence of Different Cooling Systems on the Microclimate, Photosynthetic Activity and Yield of a Tomato Crops (Lycopersicum esculentum Mill.) in Mediterranean Greenhouses. Agronomy 2022, 12, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorais, M.; Demers, D.; Papadopoulos, A.P.; Van Ieperen, W. Greenhouse Tomato Fruit Cuticle Cracking. In Horticultural Reviews; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Dunn, B.L.; Payton, M.E.; Brandenberger, L. Selection of Fertilizer and Cultivar of Sweet Pepper and Eggplant for Hydroponic Production. Agronomy 2019, 9, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madar, Á.K.; Rubóczki, T.; Hájos, M.T. Lettuce Production in Aquaponic and Hydroponic Systems. Acta Univ. Sapientiae Agric. Environ. 2019, 11, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boziné-Pullai, K.; Csambalik, L.; Drexler, D.; Reiter, D.; Tóth, F.; Bogdányi, F.T.; Ladányi, M. Tomato Landraces Are Competitive with Commercial Varieties in Terms of Tolerance to Plant Pathogens—A Case Study of Hungarian Gene Bank Accessions on Organic Farms. Diversity 2021, 13, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeev, A.C.; Raju, R.; Pan, A. Temporal Transcriptome and WGCNA Analysis Unveils Divergent Drought Response Strategies in Wild and Cultivated Solanum Varieties. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1572619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Block 1 | V6 | V5 | V4 | V3 | V2 | V1 |

| Block 2 | V1 | V6 | V5 | V4 | V3 | V2 |

| Block 3 | V2 | V1 | V6 | V5 | V4 | V3 |

| Block 4 | V3 | V2 | V1 | V6 | V5 | V4 |

| Parameter | Suitable Water Source | Well Water (ppm) | RO Unit-1st | RO Unit-2nd | Removal (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bi-carbonate | 75 | 30.50 | 6.10 | 6.40 | 79 |

| Calcium | 65 | 24.00 | 4.00 | 4.20 | 82 |

| Chlorine | 50 | 205.61 | 41.12 | 43.25 | 79 |

| Electrical Conductivity (mmhos/cm) | 0.5 | 1.02 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 78 |

| Magnesium | 22.5 | 31.08 | 7.08 | 7.30 | 77 |

| Potassium | 10 | 16.00 | 7.00 | 7.30 | 55 |

| Sodium | 30 | 138.00 | 26.0 | 27.50 | 80 |

| Sulfate | 80 | 179.53 | 38.79 | 40.12 | 78 |

| Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) | 300 | 632.40 | 130.20 | 136.8 | 78 |

| Source of Variation | df | SS | MS | F-Value | Pr > F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replication | 3 | 0.382 | 0.127 | 7.86 | n.s. | — |

| Variety (V) | 5 | 2.177 | 0.435 | 26.87 | <0.001 | *** |

| Harvest (H) | 11 | 38.401 | 3.491 | 215.40 | <0.001 | *** |

| V × H interaction | 55 | 4.111 | 0.075 | 4.61 | <0.001 | *** |

| Residual | 213 | 3.452 | 0.016 | — | — | — |

| Total | 287 | 48.523 | — | — | — | — |

| Variety | Yield (kg/Plant) | Yield (kg/m2/Harvest) | ±SE | LSD (5%) | Yield Group (p < 0.05) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torcida | 2.32 | 0.619 | 0.057 | 0.051 | a |

| Roenza | 2.23 | 0.597 | 0.069 | 0.051 | a |

| Eviva | 2.22 | 0.593 | 0.060 | 0.051 | a |

| SV 4129 TH | 2.21 | 0.591 | 0.062 | 0.051 | a |

| Lamina | 1.96 | 0.524 | 0.052 | 0.051 | b |

| Saley | 1.36 | 0.365 | 0.050 | 0.051 | c |

| Grand Mean | 2.06 | 0.548 | — | — | — |

| Variety | n | Mean Marketable Fruit (%) | SD | CLD (Sidak) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torcida | 96 | 66.27 | 23.50 | A |

| Eviva | 96 | 59.99 | 25.40 | AB |

| SV 4129 TH | 96 | 59.56 | 25.10 | AB |

| Roenza | 96 | 59.10 | 25.00 | AB |

| Lamina | 96 | 57.19 | 25.70 | B |

| Saley | 96 | 41.15 | 24.80 | C |

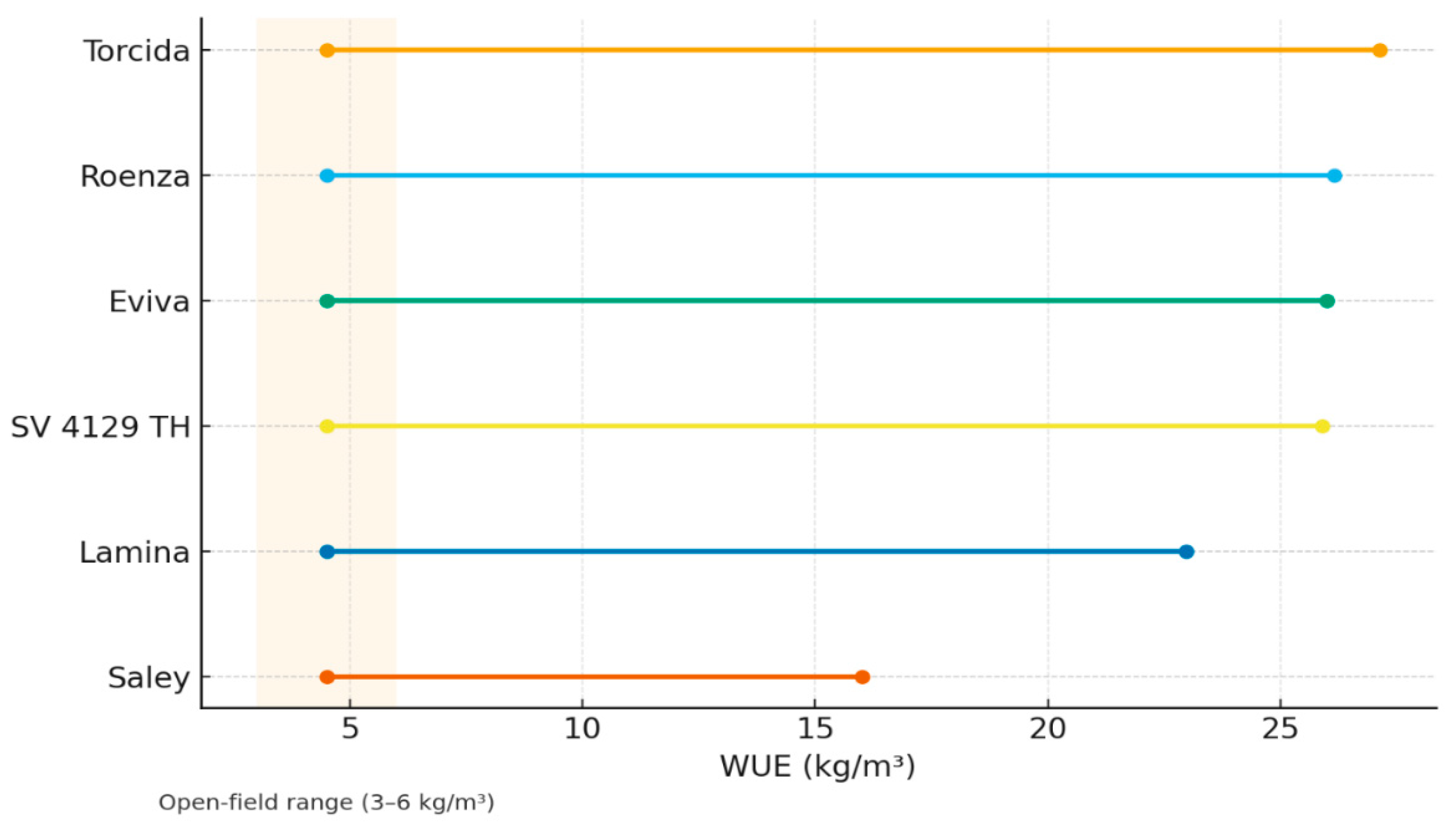

| Variety | Mean WUE (kg/m3) | ±SE | LSD (5%) | Group (p < 0.05) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torcida | 27.140 | 0.698 | 2.490 | a |

| Roenza | 26.165 | 1.877 | 2.490 | ab |

| Eviva | 26.005 | 1.048 | 2.490 | ab |

| SV 4129 | 25.903 | 1.093 | 2.490 | ab |

| Lamina | 22.973 | 1.047 | 2.490 | b |

| Saley | 16.005 | 1.051 | 2.490 | c |

| Variety | MEAN FUE (kg Yield/kg Fertilizer) | ±SE | LSD (5%) | Group (p < 0.05) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torcida | 26.490 | 0.6811 | 1.139 | a |

| Roenza | 25.540 | 1.832 | 1.139 | ab |

| Eviva | 25.383 | 1.022 | 1.139 | ab |

| SV 4129 | 25.283 | 1.066 | 1.139 | ab |

| Lamina | 22.425 | 1.023 | 1.139 | b |

| Saley | 15.623 | 1.028 | 1.139 | c |

| Item | Total Cost (UsD) | Lifespan (Years) | Annualized Cost (UsD/Year) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RO Unit | 490 | 10 | 49 |

| 0.5 HP Pump | 120 | 5 | 24 |

| Solar Power System | 730 | 5 | 146 |

| RO Maintenance | 70 | 1 | 70 |

| Well and Pump Energy Share | - | - | 136 |

| Cost of Brackish Water | - | - | 170 |

| Total Annual Cost | 595 | ||

| RO Capacity | 1550 L/day = 565.75 m3 /year | ||

| Cost of RO Water | 1.05 USD/m3 |

| Scenario | Recovery (%) | Energy Use (kWh/m) | PV Share (%) | Utilization (h/day) | Cost (USD/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base (measured) | 50 | 10.5 | 100 | 6 | 1.05 |

| Low recovery | 40 | 12.0 | 100 | 6 | 1.20 |

| High recovery | 60 | 9.0 | 100 | 6 | 0.94 |

| Lower PV | 50 | 10.5 | 70 | 6 | 1.18 |

| High PV/longer run | 50 | 10.5 | 100 | 8 | 0.97 |

| High energy price | 50 | 10.5 | 100 | 6 | 1.26 |

| Low utilization | 50 | 10.5 | 100 | 4 | 1.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nejatian, A.; Niane, A.A.; Makkawi, M.; Al-Sham'aa, K.; Shamsi, S.A.R.A.; Naqbi, T.S.A.M.A.; Ibrahim, H.Y.H.; Juma, J.E. Solar-Powered RO–Hydroponic Net House: A Scalable Model for Water-Efficient Tomato Production in Arid Regions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11298. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411298

Nejatian A, Niane AA, Makkawi M, Al-Sham'aa K, Shamsi SARA, Naqbi TSAMA, Ibrahim HYH, Juma JE. Solar-Powered RO–Hydroponic Net House: A Scalable Model for Water-Efficient Tomato Production in Arid Regions. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11298. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411298

Chicago/Turabian StyleNejatian, Arash, Abdul Aziz Niane, Mohamed Makkawi, Khaled Al-Sham'aa, Shamma Abdulla Rahma Al Shamsi, Tahra Saeed Ali Mohamed Al Naqbi, Haliema Yousif Hassan Ibrahim, and Jassem Essa Juma. 2025. "Solar-Powered RO–Hydroponic Net House: A Scalable Model for Water-Efficient Tomato Production in Arid Regions" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11298. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411298

APA StyleNejatian, A., Niane, A. A., Makkawi, M., Al-Sham'aa, K., Shamsi, S. A. R. A., Naqbi, T. S. A. M. A., Ibrahim, H. Y. H., & Juma, J. E. (2025). Solar-Powered RO–Hydroponic Net House: A Scalable Model for Water-Efficient Tomato Production in Arid Regions. Sustainability, 17(24), 11298. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411298