1. Introduction

Biochar has emerged as a pivotal interface between biomass-based energy technologies and sustainable agricultural systems. Its multifunctional role—encompassing carbon sequestration, soil fertility enhancement, and renewable energy generation—positions it as a cornerstone of contemporary sustainability frameworks [

1]. Produced via the thermochemical conversion of biomass under oxygen-limited conditions, biochar is a carbon-dense, porous, and chemically stable material capable of persisting in soils for centuries. This long-term stability allows it to function simultaneously as a renewable energy byproduct and a durable carbon sink, thereby supporting global strategies for climate change mitigation and the advancement of a circular bioeconomy [

2].

The positive impacts of biochar on soil systems are extensively documented. When incorporated as a soil amendment, biochar enhances soil structure, porosity, and aeration while improving the retention of water and essential nutrients [

3,

4]. Its large specific surface area and high cation exchange capacity stimulate microbial activity and nutrient availability, fostering optimal conditions for plant growth and increased crop productivity. Moreover, by reducing fertilizer requirements and minimizing nutrient leaching, biochar promotes more sustainable and resource-efficient agricultural practices. The stabilization of carbon within its aromatic matrix ensures long-term sequestration in soils, making biochar a promising tool for mitigating greenhouse gas emissions and rehabilitating degraded ecosystems [

5].

The versatility of biochar production arises from the broad spectrum of feedstocks that can be utilized, including agricultural residues, forestry by-products, organic wastes, and sewage sludge. Converting these materials into biochar transforms potential environmental liabilities into valuable resources, thereby enhancing resource efficiency and promoting waste valorization [

6,

7]. Within integrated biorefinery systems, biochar production can operate synergistically with bio-oil and syngas generation, contributing to the comprehensive utilization of biomass. Beyond its agronomic benefits, biochar exhibits strong potential in environmental remediation, functioning as an efficient adsorbent for heavy metals, organic pollutants, and other contaminants in soil and aquatic environments [

6,

8]. This multifunctional character highlights its pivotal role in advancing circular economy principles across diverse industrial and environmental sectors [

9,

10].

Economic feasibility remains one of the principal barriers to the widespread adoption of biochar technologies. Although biochar provides substantial environmental and agronomic benefits, its production and transportation costs can be considerable, particularly in regions with limited infrastructure or technological capacity [

11]. Integrating biochar systems within the water–energy–food–carbon nexus presents a promising strategy to enhance their economic viability. Achieving this integration requires the identification of low-cost and locally available feedstocks, the optimization of process efficiency, and the development of regional markets that internalize the environmental value of carbon sequestration [

2]. Comprehensive life cycle assessments and techno-economic analyses are essential tools for evaluating the overall sustainability of biochar systems and informing sound investment and policy decisions [

12].

Equally critical is the establishment of robust regulatory and quality assurance frameworks. The current absence of harmonized standards for biochar characterization, certification, and agricultural application has constrained confidence among producers, policymakers, and end users [

13]. Effective governance should guarantee product safety, define minimum performance and environmental quality criteria, and mitigate risks associated with contaminated feedstocks or improper use. The development and implementation of such frameworks are essential to ensure the responsible scaling of biochar technologies and to facilitate their integration into national and international sustainability and climate action agendas [

14].

The safe production and use of biochar have become a major concern, in addition to its agronomic and climate benefits. According to recent reviews, biochar may concentrate heavy metals, organic contaminants, or soluble salts when made from specific wastes, and improper control of feedstock origin and process conditions can pose risks for human exposure, food safety, and soil health [

15,

16]. Therefore, a thorough sustainability assessment must consider potential trade-offs pertaining to pollutant mobility, ecotoxicological impacts, and occupational and community safety in addition to the size of soil and climate co-benefits. These safety considerations are discussed in relation to quality standards, certification programs, and legal frameworks for the use of biochar in this review.

Future perspectives highlight the importance of interdisciplinary approaches that integrate soil science, materials engineering, and environmental policy. Advances in modeling, artificial intelligence, and digital monitoring technologies can facilitate the optimization of production systems and enable more accurate predictions of biochar performance across diverse environmental settings [

9,

17]. Similar, long-term field studies are essential to evaluate the durability of biochar effects on soil health, carbon sequestration, and greenhouse gas fluxes. Strengthening collaboration among academia, industry, and government institutions will be crucial to close existing knowledge gaps, accelerate technology transfer, and support the large-scale deployment of sustainable biochar practices [

18].

Biochar represents a pivotal technological bridge linking biomass-based energy production with sustainable agricultural systems. Its ability to enhance soil quality, sequester carbon, and integrate into renewable energy pathways positions it as a crucial element in advancing global climate mitigation and sustainability objectives [

19]. However, realizing this potential requires addressing key challenges associated with feedstock heterogeneity, process optimization, economic feasibility, and the establishment of consistent regulatory frameworks. In this context, the present work aims to examine the opportunities, challenges, and future directions of biochar as an integrative solution at the interface of energy technologies and sustainable agriculture. By aligning scientific innovation with practical implementation and policy development, biochar can play a transformative role in the transition toward a low-carbon, resilient, and circular bioeconomy.

Despite this extensive body of work, the engineering, agronomic, and climate-mitigation sectors’ present understanding of biochar is still dispersed. Few evaluations collectively look at how biomass conversion parameters control biochar quality and its subsequent performance in soils and climate mitigation. Thermochemical studies usually prioritize energy efficiency and product yields, soil science concentrates on agronomic responses, and climate literature emphasizes carbon sequestration. By combining data from different strands and offering a methodical examination of the interactions between production conditions, biochar characteristics, agronomic results, and greenhouse gas effects within biomass–biochar–agriculture systems, this review fills that gap. To address this gap, we conducted a systematic literature review following the PRISMA 2020 standards and structured by a PICO (Population–Intervention–Comparison–Outcomes) framework. The search technique covered key scientific databases (Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, SpringerLink, and Wiley Online Library) for the 2015–2025 timeframe, with specific inclusion and exclusion criteria for thermochemically generated biochar in energy–agriculture systems.

Section 2 and

Section 3 include the specific research topic, the selection strategy, and the data-extraction method.

2. Research Gap

The current understanding of biochar is still dispersed over the engineering, agronomic, and environmental domains, despite the significant expansion of biochar research. While soil science research looks at agronomic responses and climatic studies investigate carbon sequestration dynamics, thermochemical conversion studies usually focus on energy efficiency and product distribution. However, an integrated and methodically generated assessment of how biomass conversion parameters concurrently affect energy performance, the physicochemical properties of biochar, and its agronomic and climate-mitigating consequences is lacking in the literature. Transparency and the capacity to spot recurring trends across settings are hampered by most current reviews’ narrative techniques and lack of defined processes for research identification, comparison, and synthesis. Furthermore, substantial differences in feedstocks, pyrolysis conditions, soil types, and environmental settings have not been thoroughly evaluated using a single scientific framework. The following research question serves as a guide for the current study to close this gap: How do biomass conversion parameters affect energy performance, the physicochemical quality of biochar, and its agronomic and climate-mitigation consequences across various environmental and production contexts? The following goals have been established in order to accomplish the previous response: (i) identify and categorize operational parameters of thermochemical conversion processes that influence biochar yield and quality; (ii) synthesize evidence regarding the effects of biochar on soil properties, crop productivity, and greenhouse-gas emissions; (iii) assess the interactions between energy efficiency, carbon stability, and agronomic performance within integrated biomass–biochar–agriculture systems; (iv) evaluate the variability, limitations, and knowledge gaps reported in the literature; and (v) provide a systematized evidence base to support the sustainable and scalable application of biochar within circular and low-carbon development strategies.

3. Methodology: Systematic Review Protocol

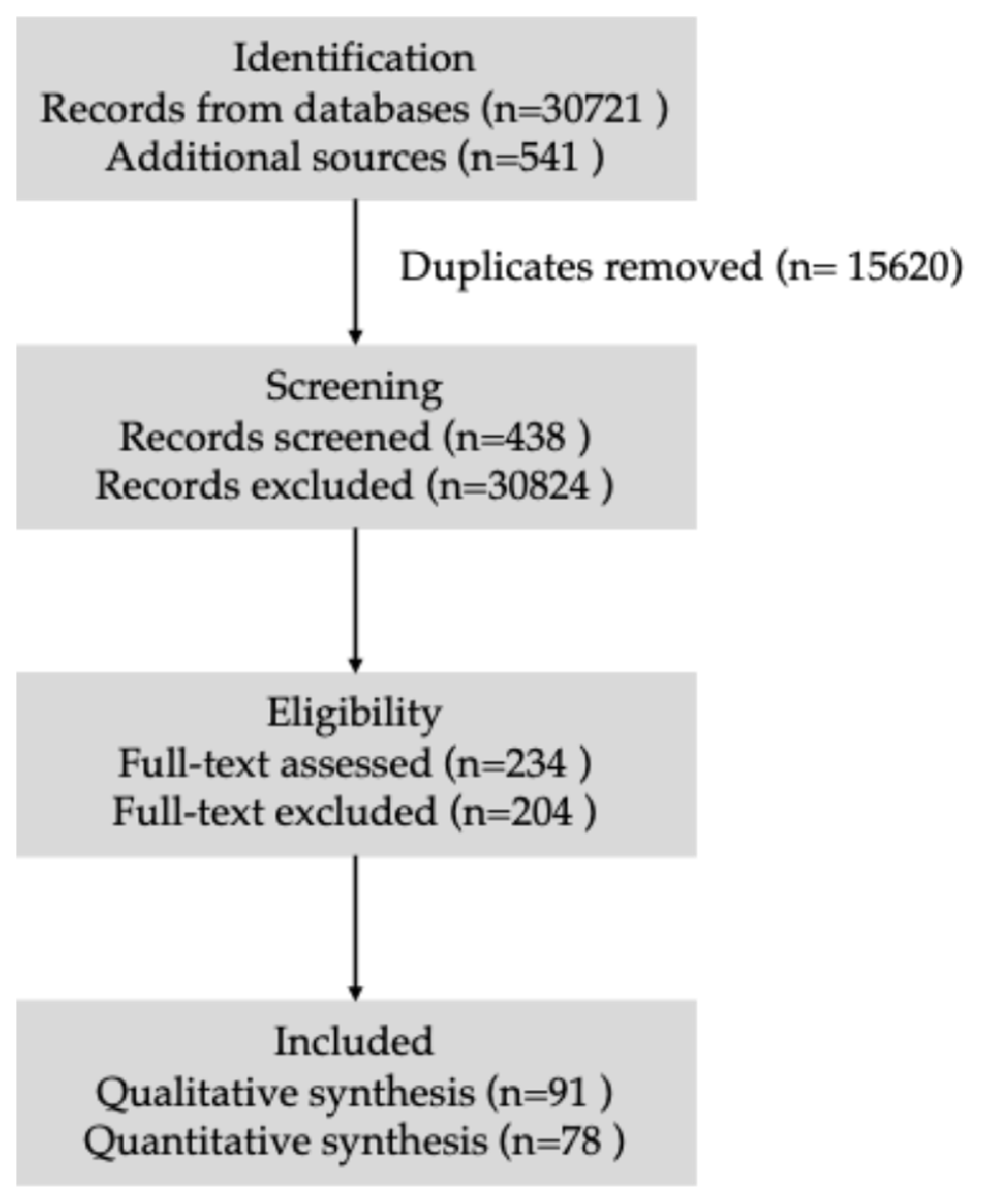

To rigorously and consistently integrate the available data on the relationship between biomass conversion parameters, biochar quality, and their agronomic and climatic consequences, this study was carried out through a systematic literature review. The study was organized using the PRISMA 2020 criteria (

Figure 1) and the PICO framework to guarantee process transparency. Initially, the various biomass types utilized to make biochar and the agricultural soils that this material has been applied to were identified as the population of interest. While the comparisons included soils without biochar application, traditional agricultural amendment alternatives, and biomass conversion systems that do not recover biochar as a co-product, the intervention under analysis specifically corresponded to the use of biochar obtained through thermochemical processes like pyrolysis, gasification, or torrefaction. The physicochemical characteristics of biochar, its impact on soil fertility, variations in agricultural production, its impacts on greenhouse gas emissions, and the energy efficiency of conversion systems were all included in the analyzed results. On the other hand, the PICO framework structured the research as follows: Population/Problem—biomass as a raw material, thermochemically produced biochar, and agricultural soils affected by its application; Intervention—use of biochar generated through pyrolysis, gasification, or torrefaction and integrated into integrated energy and agriculture systems; Comparison—absence of biochar, alternative amendments, or biomass conversion routes without biochar recovery; and Outcomes—physicochemical properties of biochar, soil improvements, crop yield responses, greenhouse gas mitigation, and energy conversion efficiency. Based on these four components, a search chain was constructed and adapted to each database: (biochar OR “biomass char”) AND (pyrolysis OR gasification OR torrefaction) AND (soil OR agriculture OR “soil fertility” OR “crop yield”) AND (“carbon sequestration” OR “greenhouse gas” OR BECCS) AND (energy OR “biomass conversion” OR “bioenergy”).

The Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, SpringerLink, and Wiley Online Library databases were then incorporated in a thorough search approach that used keyword combinations pertaining to biochar, thermochemical technologies, agricultural soils, climate mitigation, and bioenergy. A search timeframe between 2015 and 2025 was chosen to guarantee the evidence’s currency and to answer editorial concerns regarding the necessity of including new literature. The results were screened in two stages: first, duplicates were eliminated, and titles and abstracts were examined to eliminate works that were outside the scope. Afterward, the full texts were assessed to ascertain their applicability based on predetermined inclusion criteria, such as publication in peer-reviewed journals, reporting data or analyses on biochar, and addressing some energy, agronomic, or environmental aspect of the material. Excluded were theses, book chapters, conference proceedings, documents without full access, studies that only addressed syngas or bio-oil, and those that did not make use of thermochemical biochar.

Following the PRISMA framework, the number of papers that were found, screened, assessed, and finally included was recorded during the selection process. Following the selection process, qualitative data extraction was carried out, classifying the studies based on the type of biomass, the conditions of conversion, the features of the biochar that was produced, the characteristics of the soil that were examined, and the reported energy or environmental performance indicators. The discovery of patterns, differences, and information gaps about the function of biochar as a bridge between biomass conversion technologies and sustainable agriculture was made possible by this synthesis. By ensuring that the results are comparable, traceable, and indicative of current scientific knowledge, the approach used provides a strong basis for critical examination and the development of future research initiatives.

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Biochar Production in the Context of Biomass Energy Technologies

4.1.1. Principles of Biomass Conversion: Pyrolysis, Gasification, and Torrefaction

Biomass conversion technologies such as pyrolysis, gasification, and torrefaction rely on thermochemical principles to transform residual biomass into energy and carbon-rich byproducts. Residual biomasses are characterized by their composition of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin [

20]. From the above, it has been demonstrated that lignocellulosic biomass has high potential for biochar production through thermal processes [

21]. Pyrolysis involves the thermal decomposition of biomass in the absence of oxygen, typically at temperatures around 500 °C, yielding a mixture of gases (mainly hydrogen and carbon oxides), liquid bio-oils, and a solid carbonaceous residue known as biochar [

22]. Owing to its high porosity, surface area, and chemical stability, biochar has gained considerable interest for agricultural and environmental applications. Gasification, in contrast, exposes biomass to elevated temperatures (700–1500 °C) under limited oxygen conditions, producing a combustible gas (syngas) composed primarily of CO, H

2, CO

2, and CH

4 [

23]. This process involves overlapping stages of drying, pyrolysis, oxidation, and reduction, which collectively determine the composition and calorific value of the syngas used for heat and power generation or as a chemical feedstock. Torrefaction represents a milder thermochemical treatment conducted at lower temperatures (200–320 °C), designed to improve the physicochemical properties of biomass by increasing its energy density, hydrophobicity, and storage stability [

24]. Collectively, these technologies offer sustainable pathways for valorizing residual biomass, converting it into renewable energy carriers and value-added materials (

Table 1). A comprehensive understanding of the underlying mechanisms and operational parameters of each process is essential to optimize performance, enhance economic viability, and maximize their contribution to climate change mitigation and the circular bioeconomy [

25]. Depending on the lignin content of the feedstock and the operating temperature, biochar yields from slow pyrolysis usually decrease between 25 and 35 percent (dry basis) but yields from fast pyrolysis normally fall between 10 and 20 percent at 450 to 550 degrees Celsius. Due to partial oxidation, gasification generates much lower char yields (5–15%), while torrefaction yields 60–80% solid mass retention. However, because of its poor carbon stability, this substance is not regarded as true biochar. Although the current paper cannot validate this, these values offer reference ranges for comparing thermochemical pathways without making any assumptions about the behavior of the feedstock [

26,

27]. The applicability of the three main thermochemical methods for various biomass streams (woody residues, manures, and agro-residues) can be explained through a comparative study. The usual operating ranges and performance parameters mentioned in the literature are compiled in

Table 1.

4.1.2. Integration with Biomass Energy Systems

The integration of biomass energy systems that incorporate biochar production demands careful consideration of the operational parameters governing both energy yield and biochar quality. Key factors—including feedstock type, process temperature, heating rate, oxygen-limited conditions, and residence time—strongly influence system performance and product characteristics [

13,

28]. In pyrolysis-based configurations, for instance, gaseous and liquid fractions such as syngas and bio-oil can be harnessed as energy carriers, while biochar is simultaneously recovered as a solid co-product with valuable applications in soil and carbon sequestration [

29]. Such integrated systems enhance the overall efficiency of biomass utilization by coupling renewable energy generation with significant environmental co-benefits.

The quality of biochar is typically assessed through parameters such as fixed carbon content, surface area, porosity, and mineralization behavior—all directly affected by the process variables. Current research consistently demonstrates that biochar functions not only as an effective soil amendment, improving fertility and structure, but also as a durable carbon sink that reinforces the environmental and energetic sustainability of biomass conversion systems [

6,

30].

The potential of small-scale integrated systems, where thermal conversion units allow simultaneous energy production and the manufacture of biochar for soil development, has been demonstrated by studies conducted in Ecuador. In addition to this instance, comparable methods have been reported in several areas [

31,

32]. Field tests conducted in arid and semi-arid potato farmland in China reveal that biochar produced at regulated pyrolysis temperatures greatly improves soil hydraulic properties, including porosity, water retention, and aggregate stability, and boosts crop yields [

33]. This illustrates how integrated biomass–biochar systems can support agricultural productivity and energy. Biochar has been integrated into larger residue-management techniques within circular economy frameworks in India, where agricultural wastes surpass 500 million tons per year. Using rice husk, bagasse, and other agricultural wastes as feedstocks, these systems produce biochar in a decentralized manner that simultaneously improves soil fertility, generates renewable energy, and lowers open field burning [

34,

35]. Rice husk and sugarcane bagasse are pyrolyzed in West Africa, especially Nigeria, to create nutrient-rich biochar that supply vital minerals and improve acidic soils. This biochar is part of locally embedded valorization pathways, where they serve as a soil amendment and a way to turn unmanaged agricultural residues into useful resources [

36]. When taken as a whole, these examples from Asia, Africa, and Latin America show that the integration of biomass conversion technologies with agricultural systems is not geographically isolated but rather part of a larger global trend where biochar acts as a bridge between soil restoration, sustainable residue management, and the production of renewable energy.

The integration of energy production with biochar recovery thus provides a viable pathway toward sustainable waste valorization, enabling the generation of renewable energy while mitigating climate change through long-term carbon stabilization in soils. These interdisciplinary approaches support the advancement of circular bioeconomy models and contribute to broader sustainable development goals [

37].

4.1.3. Factors That Affect Biochar Quality

The physical and chemical properties of biochar—such as bulk density, fixed carbon content, stability, specific surface area, surface functional groups, and pH—are strongly governed by the nature of the feedstock and the conditions of the thermochemical conversion process. Among these factors, pyrolysis temperature exerts the greatest influence: increasing temperature enhances fixed carbon content and structural stability, thereby improving the long-term persistence of biochar as a carbon sink [

19]. However, elevated temperatures typically reduce overall biochar yield. The heating rate and residence time also play critical roles in determining pore development and chemical composition, which in turn affect water retention capacity, nutrient adsorption, and interactions with soil microbiota. Additionally, reactor configuration, the presence of volatile vapors, and post-treatment processes can further modify these physicochemical characteristics, tailoring biochar for specific applications [

5,

38]. The following are common analytical techniques for characterizing biochar: (i) BET nitrogen adsorption for specific surface area and porosity; (ii) SEM/EDS for morphological analysis; (iii) FTIR and XRD for functional groups and mineral phases; and (iv) ICP-OES/ICP-MS for heavy metal quantification after acid digestion (e.g., EPA 3051A). It is crucial to report these techniques to standardize findings across research. Several recent reviews offer comprehensive summaries of the manufacturing and uses of biochar. The authors focus on production technology, characterization methods, and environmental applications across many industries while examining eco-friendly manufacturing routes and a variety of applications of biochar for ecosystem stability and climate change mitigation [

5,

6,

16]. Other studies focus on the safe and sustainable application of biochar in soils, highlighting the advantages and possible dangers related to pollutants and ecotoxicity [

16]. The explicit integration of thermochemical conversion parameters, energy performance measures, biochar physicochemical quality, agronomic responses, and greenhouse gas outcomes into a single biomass–biochar–agriculture framework sets the current review apart from these investigations. Instead of focusing on research goals within a single disciplinary domain, this integrated approach enables us to discover cross-domain trade-offs (such as between energy yield and carbon stability) and to highlight research needs at the interface of energy technologies and sustainable agriculture (

Figure 2).

4.2. Agricultural Application of Biochar: Benefits and Mechanisms

4.2.1. Improvement of Soil Properties

The incorporation of biochar into soils can markedly enhance key physicochemical and biological properties that underpin soil health. Owing to its high porosity, biochar improves soil water retention—an especially valuable function in sandy or degraded soils prone to rapid moisture loss [

39,

40,

41,

42]. In addition, biochar increases the soil’s cation exchange capacity, promoting nutrient retention and gradual release, reducing nutrient leaching, and improving fertilizer use efficiency [

43,

44]. Another important effect is the amelioration of soil acidity, as biochar can neutralize hydrogen ions and elevate pH levels in acidic soils, thereby creating more favorable conditions for microbial activity and plant nutrient uptake [

4,

45,

46]. The organic matter contributions from biochar improve the soil’s carbon content, which in turn has a positive effect on soil structure, cation exchange capacity, and soil buffering capability [

45].

Biochar also provides a stable habitat for beneficial microorganisms due to its porous structure and large specific surface area, which facilitate the colonization and proliferation of bacteria and fungi essential for soil biogeochemical processes [

47]. Enhanced microbial activity contributes to the formation of stable organic matter and overall improvements in soil quality. Moreover, by sustaining optimal moisture levels, nutrient availability, and structural stability, biochar can strengthen plant resilience to environmental stress, resulting in healthier and more productive crops [

46,

48].

The addition of biochar to the soil also enhances microbial activity. It has been observed that applying biochar to the soil increases the activity of enzymes such as urease [

44]. Beyond its agronomic benefits, the capacity of biochar to store stable carbon in soils underscores its role as an effective tool for mitigating climate change through long-term atmospheric carbon sequestration. Mean crop yield improvements of 10–20% are reported by meta-analyses, with greater responses (30–40%) shown in tropical soils that are acidic and low in nutrients. However, site-specific validation is still crucial because these values differ significantly based on soil type, treatment rate, and co-application with fertilizers [

44].

4.2.2. Carbon Sequestration and Climate Change Mitigation

Biochar represents a promising strategy for carbon sequestration and climate change mitigation owing to its capacity to stabilize carbon in soils over extended timescales—ranging from several decades to millennia—depending on the production conditions and soil environment [

49]. This long-term stability enables biochar to function as an effective carbon sink, preventing the return of stored carbon to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide and thereby contributing to net reductions in greenhouse gas concentrations. Owing to this property, biochar has been increasingly recognized as a negative emissions technology, particularly when integrated into biomass-based energy systems within the bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) framework [

2,

42,

45]. In such systems, biomass serves as both an energy source and a precursor for biochar production, with the resulting material applied to soils to ensure stable carbon sequestration. Beyond direct carbon storage, biochar can beneficially influence native soil carbon dynamics by inducing a negative priming effect that suppresses the mineralization and emission of existing soil organic carbon, further enhancing its mitigation potential [

50]. Its addition also stimulates microbial biomass and activity, promoting the formation of stable organo-mineral complexes and persistent organic matter.

Regarding the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, biochar has the potential to reduce N

2O and CH

4 emissions from agricultural practices [

51]. It has been estimated, for example, that the application of biochar to soil can reduce N

2O emissions by up to 38% [

51]. Some studies show increases in CO

2 or CH

4 after applying biochar, whereas many claim decreases in N

2O and CH

4 emissions. These increases are frequently associated with (i) increased soil aeration speeding up native carbon mineralization, (ii) labile carbon fractions in fresh biochar promoting microbial respiration, and (iii) altered redox conditions boosting methanogenesis in poorly drained soils. These mechanisms emphasize how crucial it is to assess the interactions between biochar and soil under site-specific hydrological and biochemical circumstances [

52].

The literature reports CO

2-equivalent mitigation potentials that range from 1 to 35 t CO

2-eq ha

−1 yr

−1, depending on soil type, carbon stability, and avoided fertilizer emissions [

53,

54,

55]. In this regard, it has been suggested that soil pH, the biochar C:N ratio, and the biochar application rate are the most influential variables affecting soil CH

4, CO

2, and N

2O emissions [

51,

56]. On the other hand, it has been observed that the application of biochar can increase CO

2 and CH

4 emissions in agricultural systems. The effects of biochar application on greenhouse gas emissions depend on the type of biochar and soil; therefore, site-specific and material-specific studies should continue to be conducted [

51].

In addition, biochar can be used as an agricultural input to promote low-carbon farming. These practices include: (i) the use of biochar as a nutrient carrier matrix through the formulation of slow-release biochar-based fertilizers [

4,

57], and (ii) the use of biochar as an additive in composting [

56]. In both cases, the formulation of biochar-based bio inputs has proven to be a promising alternative for incorporating biochar into agricultural practices, potentially helping to reduce dependence on chemically synthesized agricultural inputs, e.g., nitrogen fertilizers, which have been associated with negative impacts such as higher greenhouse gas emissions throughout their life cycle [

58].

Together, these processes position biochar as a robust and sustainable tool that improves soil quality and agricultural productivity and serves as a key component in the transition toward low-emission, climate-resilient agroecosystems with active atmospheric carbon capture [

59].

4.2.3. Synergies Between Energy, Agricultural Waste and Soil Fertility

The utilization of agricultural waste for energy generation and biochar production has become a strategic component of modern circular economy and energy transition frameworks. In this approach, residual biomass—often underexploited or disposed of through practices that contribute to greenhouse gas emissions and environmental degradation—is converted through thermochemical processes into renewable energy carriers and a carbon-rich co-product with high agronomic value [

60]. This transformation enables the closure of material and energy cycles, following the pathway: waste → energy + biochar → soil enhancement → increased productivity → reduced dependence on chemical inputs. Integrating these processes not only alleviates pressure on landfills and final disposal systems but also provides a renewable substitute for fossil fuels, promoting energy self-sufficiency within agricultural and rural systems. At the same time, the incorporation of biochar into soils enhances nutrient and water retention, improves soil structure, and strengthens resilience to climatic stress [

61]. As a result, agricultural systems can decrease their reliance on synthetic fertilizers and external substrates, lowering production costs while conserving natural resources. Altogether, the combined use of bioenergy and biochar derived from agricultural residues represents a holistic and synergistic strategy that interlinks sustainable waste management, renewable energy production, and soil restoration [

62]. This integrated model delivers significant environmental, economic, and social benefits, reinforces global sustainability objectives, and opens new opportunities for innovation and value creation across rural and agro-industrial value chains.

4.3. Opportunities for Biomass-Agriculture Systems

4.3.1. Waste Valorization and Circular Economy

Biochar production offers an effective pathway for the valorization of agricultural, forestry, and urban wastes by transforming materials that are often underutilized or improperly managed—such as those subjected to open burning or uncontrolled disposal—into a value-added product with diverse applications [

63]. This process aligns directly with the principles of the circular economy by reintegrating the carbon and nutrients contained in organic residues back into productive cycles, thereby reducing waste volumes and mitigating emissions associated with their natural degradation or combustion. From an environmental standpoint, the conversion of residual biomass into biochar significantly reduces greenhouse gas emissions and air pollutants by preventing the release of carbon dioxide, methane, and fine particulate matter that would otherwise result from decomposition or open burning [

64]. Moreover, the stabilization of carbon within the biochar matrix facilitates its long-term sequestration in soils, providing additional climate mitigation benefits. Economically, biochar production from waste streams creates new market opportunities, including its commercialization as a soil amendment, its use in the development of high-value products such as adsorbents, substrates, or composite materials, and its potential inclusion in carbon credit and emissions offset schemes [

2,

6]. Waste valorization through biochar production not only mitigates environmental impacts but also supports the development of sustainable and resilient business models that integrate waste management with agricultural productivity and renewable energy generation—contributing to a circular, low-carbon economy [

65].

The promise of biochar systems is reinforced by cross-sector experiences in implementing the circular economy. Recent research in the mining industry, for instance, shows effective closed-loop models for waste reuse and tailings valorization (e.g., [

66,

67]). These examples show how industrial waste can be repurposed as secondary raw materials, lowering environmental risks and generating new revenue. The claim that circular systems based on biochar can be extended beyond agriculture and assist broader industrial ecology efforts is strengthened by the inclusion of such similarities.

4.3.2. Integration with Carbon Programs and Climate Finance

Biochar’s exceptional capability to store carbon in stable, long-lived forms creates concrete opportunities for its integration into climate mitigation and green finance frameworks. By locking carbon into recalcitrant structures that persist for centuries, biochar delivers measurable and verifiable climate benefits that fit the criteria of voluntary carbon markets, ecosystem service payment schemes, and national emission reduction programs [

68]. Recognizing the value of carbon retained in soils through biochar use enhances the profitability of biomass–biochar systems and motivates their adoption across rural and agro-industrial sectors. Biochar moves beyond its traditional role as a soil amendment to function as a climate asset within sustainable value chains, generating financial returns tied to improved soil productivity and verified emission reductions [

69]. Embedding biochar in international climate finance instruments—such as green funds, carbon credit programs, and clean development mechanisms—can attract investment toward decentralized technologies that convert waste into renewable energy and stable carbon pools. This integrated model advances agricultural decarbonization while reinforcing circular economy strategies in which waste valorization yields tangible environmental and economic gains [

68].

4.3.3. Improved Agricultural Productivity and Reduced Inputs

The application of biochar in agricultural systems represents an effective strategy for improving soil quality and optimizing input use, thus contributing to more efficient and sustainable production. Thanks to its high porosity, large specific surface area, and abundance of active functional groups, biochar improves water and nutrient retention, increases cation exchange capacity, and stimulates soil microbial activity [

13,

48]. These physical and chemical properties foster a more stable and fertile root environment, promoting more vigorous and sustained plant growth. The incorporation of biochar into agricultural soils can significantly reduce dependence on synthetic fertilizers by improving nutrient use efficiency and decreasing losses due to leaching [

70]. This characteristic is particularly relevant in regions with economic or logistical limitations in accessing chemical fertilizers, as well as in soils with low nutrient retention capacity. Furthermore, the porous structure of biochar contributes to improved water efficiency by reducing evapotranspiration and increasing water availability in the root zone, resulting in greater resilience to drought conditions [

48,

71]. In tropical and subtropical regions, where soils are often highly weathered and poor in organic matter, biochar acts as a soil fertility restorer, helping to recover the productivity of degraded lands and maintain the stability of agricultural systems in the face of climate variations. Its integration into agroecological practices and sustainable soil management programs can therefore increase agricultural productivity, improve food security, and reduce the environmental footprint of primary production [

72].

4.3.4. Technological Flexibility and Scalability

Biomass conversion technologies exhibit remarkable flexibility in design and operation, enabling their deployment across diverse production contexts—from small-scale agricultural systems to large industrial facilities. This technological adaptability enhances the feasibility of the integrated energy–biochar–sustainable agriculture model by allowing systems to adjust to local conditions of biomass availability, infrastructure capacity, and energy demand [

73]. In rural or small-scale settings, modular pyrolysis and gasification units can be implemented in a decentralized manner, utilizing agricultural residues on-site and minimizing the costs associated with transportation and material handling. At the industrial level, medium- and large-scale conversion facilities can integrate bioenergy generation with the co-production of biochar and other value-added materials, thereby optimizing the energy potential of biomass while delivering multiple environmental and economic benefits [

61]. The valorization of co-products such as biochar further diversifies revenue streams, reducing dependence on energy sales alone. Biochar can serve as an agricultural amendment, an environmental adsorbent, or a precursor for advanced materials, while the gaseous and liquid fractions produced during pyrolysis can be utilized as fuels or chemical feedstocks [

13]. This diversification enhances process profitability, mitigates economic risk, and reinforces the long-term sustainability of biomass conversion systems.

4.4. Challenges and Barriers

4.4.1. Technical and Economic Divergences

Despite the increasing interest in biochar production and use, several technical and economic barriers continue to limit its widespread adoption and integration into agricultural and energy systems. Economic feasibility remains one of the most significant challenges, as the costs associated with biomass conversion—capital investment, equipment operation and maintenance, feedstock transport, drying, and post-processing—vary substantially across contexts [

74]. These costs depend on production scale, feedstock type and availability, local energy and fertilizer prices, and the presence of incentives related to emissions reduction or carbon credit generation. As a result, small-scale systems may benefit from reduced logistics and handling costs, whereas large-scale facilities rely on economies of scale, creating markedly different economic landscapes across regions and production models [

75]. It has been estimated that large-scale biochar production can cost between

$220 and

$346 per ton, while small-scale production costs approximately

$400 per ton. These values may vary depending on the production site, labor costs, and other previously mentioned factors [

21]. Economic feasibility studies have shown that the co-production of biomass-derived energy and biochar is the most promising pathway for future projects [

21,

32]. Om the other hand, the agricultural use of biochar has shown economic benefits. For instance, the combination of biochar with NPK fertilizers and rhizobacteria increased wheat yield and net profits per hectare. Similarly, co-composting with biochar boosted maize production by 243%, generating net profits of over

$1.000 per hectare [

21].

A second constraint stems from the heterogeneous performance of biochar in agricultural soils. Its effectiveness varies not only because of differences in feedstock composition, pyrolysis temperature, and operating conditions but also due to the specific physicochemical characteristics of each soil [

5]. While numerous studies report substantial benefits in degraded, acidic, or tropical soils, responses in temperate or nutrient-rich soils are often more modest or uncertain. This variability complicates efforts to standardize application rates and agronomic recommendations, highlighting the need to evaluate biochar performance under context-specific conditions of climate, texture, fertility, and crop management [

76].

A third critical challenge involves competition for biomass resources. In many regions, agricultural and forestry residues suitable for biochar production are also demanded for pellet manufacturing, biofuel generation, animal bedding, or direct combustion for heat and power [

77]. This competition can constrain feedstock availability, increase raw material costs, and undermine the sustainability of the supply chain. The relative priority of these competing uses depends on economic conditions, logistical considerations, regulatory frameworks, and regional strategies related to ecosystem services and climate mitigation [

77]. Economic analyses reveal that the cost of feedstock, transportation distance, and the value of carbon credits have a significant impact on the profitability of biochar. Feedstock price fluctuations of ±25% might cause net present value (NPV) to change from positive to negative, according to techno-economic studies. Depending on the use of co-products (heat, syngas, and bio-oil), decentralized pyrolysis units usually have payback times of 4 to 9 years. The supplied manuscript only contains general published ranges because I am unable to verify precise figures for each technology [

78,

79].

4.4.2. Regulations, Standards and Product Quality

The development and large-scale deployment of biochar—as both an agricultural amendment and a climate-mitigation tool—depend on the establishment of robust regulatory frameworks and consistent quality standards [

48]. A major challenge, however, lies in the absence of harmonized international criteria governing key properties such as heavy metal and organic contaminant concentrations, carbon stability, ash content, particle size, and minimum agronomic performance thresholds. This regulatory fragmentation complicates product comparison, limits participation in international markets, and undermines confidence among farmers, companies, and oversight agencies [

13,

80]. The creation of verifiable and widely accepted standards therefore represents a critical step toward ensuring the safety, effectiveness, and traceability of biochar across its diverse applications. The expansion of the biochar sector also requires guarantees that the biomass used as feedstock originates from sustainable sources. Without such safeguards, rising biomass demand could encourage counterproductive practices, including the conversion of natural ecosystems, the overharvesting of forest residues, or competition with crops intended for food and feed [

37]. Certification schemes that verify responsible biomass sourcing, protect ecosystem services, and align with conservation and sustainable land-use policies are therefore essential. Integrating quality standards, certification systems, and clear regulatory guidelines will protect the environmental and agronomic integrity of biochar, reinforce market confidence, facilitate international trade, and support the adoption of biomass conversion technologies consistent with long-term sustainability and decarbonization objectives [

81].

4.4.3. Agronomic and Implementation Issues

The incorporation of biochar into agricultural systems raises a set of agronomic and operational questions that require targeted research to ensure its safe, efficient, and sustainable use. One of the central challenges involves identifying optimal application rates and methods, which depend on soil type, crop species, climate, and management practices [

13]. Application strategies may include direct incorporation into the soil, surface application, or co-application with compost, fertilizers, or beneficial microorganisms. Because each strategy can produce distinct responses in soil structure, nutrient cycling, and crop performance, medium- and long-term field studies are essential for developing context-specific recommendations [

82].

Although biochar is widely associated with improvements in soil function, inappropriate application rates or methods can generate unintended effects. Several studies report that excessive biochar inputs may alter soil microbial communities, modify the availability of key nutrients, or reduce the efficacy of fertilizers and pesticides, particularly when these inputs interact with the chemical or physicochemical properties of biochar surfaces [

83]. These potential interactions highlight the need for a deeper understanding of the mechanisms governing biochar–soil–plant–microbe dynamics.

Logistical considerations also pose important challenges. Transporting large volumes of biomass to conversion facilities and subsequently distributing biochar to agricultural fields can increase both operational costs and greenhouse gas emissions, potentially offsetting some of the system’s environmental benefits [

84]. Consequently, decentralized production models located near feedstock sources and end users—combined with optimized supply chain logistics—are critical to enhancing economic and environmental performance and ensuring the practical scalability of biochar-based interventions [

6]. Farmers’ adoption is impacted by several challenges, including inadequate extension services, restricted access to biochar providers, ignorance of proper application rates, and ambiguity about agronomic benefits. Underexplored educational barriers, such as lack of experience with thermochemical technology and worries about contamination dangers, necessitate focused training programs, demonstrations, and farmer-led trials.

4.4.4. Scalability and Regional Context

The implementation of biochar within agricultural and energy systems cannot be approached as a universal solution; instead, its performance depends strongly on regional conditions. Soil type, climate, dominant cropping systems, infrastructure, technical capacity, and the broader political and institutional landscape all shape the feasibility and effectiveness of biomass- and biochar-based initiatives [

69]. As a result, practices that demonstrate success in one region cannot be assumed to translate directly to others, particularly where significant differences exist in biomass availability, agricultural structures, or socioeconomic priorities. Scaling biochar use therefore requires context-specific strategies that account for the ecological, productive, and institutional characteristics of each territory [

69]. Ensuring the sustainability of biomass–biochar systems also demand safeguards against unintended environmental and social impacts. In some regions, redirecting residues toward biochar production may compete with essential traditional uses—such as firewood for rural households, animal bedding, or soil mulching—and could jeopardize local livelihoods [

85]. Rising biomass demand may also intensify pressure on forest ecosystems, increasing the risk of overharvesting, reductions in vegetation cover, or indirect drivers of deforestation. These risks underscore the importance of establishing rigorous sustainability criteria and certification mechanisms that verify responsible feedstock sourcing and protect local ecosystem services [

86]. A territorial approach that integrates environmental, socioeconomic, and logistical assessments is fundamental for evaluating realistic opportunities to scale biochar without compromising sustainability. Through context-aware adaptation and strategic planning, biochar can be effectively incorporated into regional strategies for sustainable agriculture, bioeconomy development, and climate mitigation [

87]. The effectiveness of biochar varies depending on the climate zone. Tropical and subtropical soils, which are typically acidic, low-CEC, and poor in organic matter, show the biggest gains, whereas temperate soils typically show small or inconsistent responses. Applications in arid zones can promote water retention, but to prevent excessive pH increases, they might need to be co-applied with compost. The debate is still qualitative since the manuscript does not offer a quantitative climatic classification of the collected research.

4.5. Future Directions of Research and Policy

4.5.1. Technical Research

Advancing biochar as a tool for the energy transition and sustainable agriculture requires a robust research agenda capable of resolving existing uncertainties and informing the design of integrated systems. A central priority is the standardization of production methodologies, particularly the optimization of pyrolysis conditions to maximize both energy yield and biochar quality [

13]. Key properties—such as fixed carbon content, porosity, surface chemistry, and carbon stability—must be consistently quantified using comparable metrics to enhance product reliability and support its effective use in agricultural and environmental applications [

88]. Long-term field studies are equally essential. Evaluating biochar performance across diverse soils and climatic conditions requires sustained monitoring of soil carbon dynamics, microbial community shifts, nutrient availability, crop productivity, and non-CO

2 greenhouse gas emissions (e.g., N

2O and CH

4) [

12]. Such evidence is critical for generating agronomic recommendations that reflect both the benefits and potential risks of biochar application over timescales relevant to agricultural decision-making [

49].

In parallel, comprehensive life cycle assessments (LCAs) and techno-economic analyses are needed to evaluate the technical, environmental, and financial viability of biomass–biochar systems. These assessments should encompass all stages—from biomass collection, transport, and drying to thermochemical conversion, field application, and the resulting agronomic and climatic outcomes, including potential revenue from carbon credits [

77]. A holistic perspective is essential for identifying bottlenecks, comparing technological pathways, and defining efficient implementation strategies. Exploring synergies between biochar and other sustainable agricultural practices represents another key research direction. Interactions with organic fertilizers, conservation agriculture, and agroforestry systems may enhance soil health and system resilience [

89]. Likewise, examining how biochar integrates with biomass energy technologies—such as cogeneration, biogas production, and gasification—can support the development of multifunctional systems that maximize energy efficiency and environmental benefits [

11].

Strengthening technical research must be accompanied by the creation of best-practice guidelines covering feedstock selection, conversion technology design and operation, biochar characterization and monitoring, and agronomic application protocols [

13]. These guidelines should align with emerging carbon policies and the needs of farmers, industry, and regulatory agencies to ensure the responsible, scalable, and context-appropriate adoption of biochar across sectors [

90].

4.5.2. Policies, Incentives and the Market

Developing biochar-based value chains requires a regulatory and market environment that enables production, commercialization, and adoption while safeguarding environmental and social sustainability. Central to this effort is the establishment and harmonization of international quality standards governing heavy metal content, carbon stability, organic contaminants, and feedstock traceability [

91]. Robust and comparable standards build market confidence, protect soil and ecosystem health, and prevent practices that could undermine the environmental integrity of biochar. In parallel, economic instruments must evolve to recognize the full spectrum of biochar’s benefits—including renewable energy generation, carbon sequestration, and soil fertility enhancement [

92]. Strategic subsidies, carbon credit mechanisms, and payment-for-ecosystem-services programs can mobilize investment, lower financial barriers for farmers and biomass operators, and accelerate the transition toward circular and low-emission production systems [

93].

Strengthening residual biomass supply chains represents another priority. Sustainable collection of agricultural and forestry residues, efficient transportation logistics, and the deployment of local conversion infrastructure are essential components of integrated territorial strategies [

94]. Such approaches reduce logistical costs, lower transport-related emissions, and enhance rural economic resilience by fostering decentralized value chains. Capacity building also plays a critical role. Training programs for farmers, biomass operators, and rural stakeholders are necessary to support the effective adoption of conversion technologies and to ensure the agronomic and technical soundness of biochar applications [

95,

96]. Knowledge transfer through extension services and advisory networks can significantly accelerate the integration of biochar into agricultural and energy practices at multiple scales [

93].

To incorporate biomass consumption, biochar production, and soil improvement into coherent resource management strategies, territorial policies must be assessed and coordinated [

97]. These regulations should support sustainable land-use practices, limit competition with food security goals, and prevent pressures on biodiversity. Building a robust and sustainable biochar market requires a governance system that concurrently tackles social, economic, and environmental aspects [

98].

5. Limitations

Despite the methodical and methodologically structured methodology used in this analysis, several limitations must be recognized to contextualize the findings’ dependability and scope. First, one of the main limitations of biochar study is its intrinsic heterogeneity. Direct comparisons are difficult because studies vary greatly in terms of biomass feedstocks, thermochemical conversion conditions, reactor layouts, heating rates, and post-treatment procedures. These variances also apply to agronomic experiments, where results are influenced in ways that are not always completely reported or comparable due to variations in soil type, climate, crop species, irrigation schedules, and management techniques. The generalizability of certain findings may be restricted to certain operational or environmental contexts and integrating results across such disparate methodological settings creates ambiguity.

Second, inconsistencies and gaps in reporting standards in the literature provide a second constraint. The depth of cross-study analysis is limited by the fact that many primary studies lack comprehensive information on crucial factors like carbon stability, surface chemistry, porosity measurements, or exact reactor operating parameters. The integration of results is made more difficult by the lack of consistent metrics for evaluating soil responses, such as standardized units for microbial activity, nutrient retention, or greenhouse gas fluxes. Furthermore, some research relies on small sample sizes, short-term experiments, or laboratory conditions that could not fully reflect field reality, while others claim statistically sound results.

Third, despite being thorough, the search technique was limited to peer-reviewed literature released between 2015 and 2025. Although this temporal filter was designed to guarantee the inclusion of recent and significant studies, it might have left out previous fundamental research that could offer more mechanistic insights or historical background. Similarly, limiting the review to English-language literature would have left out pertinent research from areas where biochar is often used but published in other languages. These omissions create a possible chronological and linguistic bias that could affect how representative the final body of data is.

Another methodological drawback is publication bias. While neutral or negative findings continue to be underreported, studies with significant or favorable results—especially those showing agronomic gains or greenhouse gas mitigation—are more likely to be published. This disparity may result in an overestimation of biochar’s advantages and an underrepresentation of situations when it has little or no impact. Results interpretation may be impacted by this imbalance, especially when it comes to highly variable outcomes like soil microbial reactions or crop output.

The lack of long-term field studies is another drawback. The long-term dynamics of biochar stability, nitrogen cycling, and ecological interactions are not adequately captured by the short periods and controlled laboratory or greenhouse conditions used in many investigations. Short-term studies only offer limited insights because processes like carbon sequestration, soil structure evolution, or microbial community alterations take years or decades to complete. This time discrepancy highlights the necessity of prolonged observation to confirm and improve existing knowledge.

In addition, there are still few integrated evaluations in the literature that concurrently analyze agronomic, energy, and climate-related effects, which limits the capacity to make comprehensive judgments regarding the multifunctional role of biochar within circular bioeconomy systems. Techno-economic evaluations and life-cycle assessments are still comparatively rare and frequently rely on generalized data or assumptions that do not accurately reflect site-specific reality. Therefore, additional empirical validation of the scalability and practicality of combined biomass–biochar–agriculture systems is necessary. All these drawbacks point to the necessity of interdisciplinary research projects, standardized reporting procedures, harmonized methodological frameworks, and long-term field assessments that together bolster the body of evidence and encourage the widespread use of biochar in sustainable agricultural and energy systems.

6. Conclusions

Biochar is a strategic relationship between biomass-based energy systems and sustainable agriculture, allowing a rare chance to address soil degradation, carbon emissions, and waste management concurrently. While many studies have looked at agronomic responses, carbon sequestration, or energy performance separately, few integrate these domains to evaluate how biomass conversion parameters collectively influence biochar quality, soil outcomes, and greenhouse gas dynamics across diverse environmental settings. This review fills a persistent gap in the literature by combining evidence from thermochemical conversion, soil science, and climate-mitigation research. Our synthesis indicates that when created under well-controlled thermochemical conditions and applied to correctly selected soils, biochar may concurrently valorize organic residues, boost soil function, support renewable energy production, and stabilize carbon over extended periods.

The findings clarify various cross-domain trade-offs. Higher conversion temperatures enhance carbon stability but limit biochar output, and agronomic benefits can be negated by possible dangers from impurities or inadequate application methods. These interactions underline the need to prioritize sustainable and traceable feedstocks, optimize pyrolysis conditions to balance energy efficiency and carbon stability, and customize biochar formulations and application rates to specific soil types and cropping systems. The paper also emphasizes how, when implemented under context-specific technical and environmental conditions, integrated biomass–biochar–agriculture systems can reduce reliance on chemical inputs, conform with circular economy concepts, and significantly contribute to climate mitigation.

Biochar needs to be purposefully incorporated into agriculture and climate policies in order to facilitate widespread adoption. National harmonization of quality standards and certification schemes is crucial to assure product safety, ensure feedstock traceability, and generate confidence among farmers, regulators, and carbon market operators. Integrating biochar into soil-restoration strategies—particularly in degraded tropical and subtropical soils—would enhance its agronomic and climate benefits. Biochar should be integrated into climate-finance mechanisms like voluntary carbon markets, payment-for-ecosystem-services schemes, and national greenhouse gas reduction programs because of its ability to safely store carbon in resistant forms. This would create financial incentives that encourage investment in decentralized biomass conversion technologies.

Supply chains for residual biomass must be strengthened. By coordinating local preprocessing, decentralized thermochemical conversion, and sustainable biomass extraction, territorial planning can lower logistical emissions, lessen competition with alternative residual applications, and increase the viability of biochar production economically. Local and rural development initiatives might also profit from modular and small-scale pyrolysis or gasification units that valorize surrounding residues while supplying farmers with biochar at a cheaper cost. To overcome adoption challenges associated with confusion about application rates, contamination hazards, and the operation of thermochemical technologies, more extension services, training programs, and farmer-focused demonstration projects are required.

Furthermore, long-term field trials and integrated life cycle and techno-economic assessments are needed to improve the empirical basis for national-scale deployment. Multi-year studies that monitor soil carbon dynamics, nitrogen cycling, crop productivity, and greenhouse gas fluxes across varied climates will offer the evidence required to modify agronomic recommendations and assure environmental safety. Simultaneously, thorough evaluations of biomass-biochar systems—from feedstock gathering to conversion, application, and carbon credit creation—will assist policy choices meant to scale biochar within more comprehensive frameworks for sustainable development and decarbonization.

When supported by strong governance, rigorous scientific evidence, and targeted policy instruments, biochar can become a transformative tool for soil restoration, waste valorization, rural development, and climate mitigation. Its integration into national agricultural and climate strategies can contribute to the development of resilient, low-carbon, and circular bioeconomy, ensuring that the co-benefits documented in this review translate into broad and equitable on-the-ground impacts.