Academic Adaptation and Performance Among International Students in China: The Mediating Role of Student Engagement

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Is there any significant influence of academic adaptation on academic performance among international students in China?

- Is there any significant influence of academic adaptation on student engagement among international students in China?

- Is there any significant influence of student engagement on academic performance among international students in China?

- Is there any significant mediating influence of student engagement on the relationship between academic adaptation and academic performance among international students in China?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Academic Performance

2.2. Academic Adaptation

2.3. Student Engagement

2.4. Transformative Theory

2.5. Hypotheses and Conceptual Model

2.5.1. The Relationship Between Academic Adaptation and Academic Performance

2.5.2. The Relationship Between Academic Adaptation and Student Engagement

2.5.3. The Relationship Between Student Engagement and Academic Performance

2.5.4. Mediating Role of Student Engagement

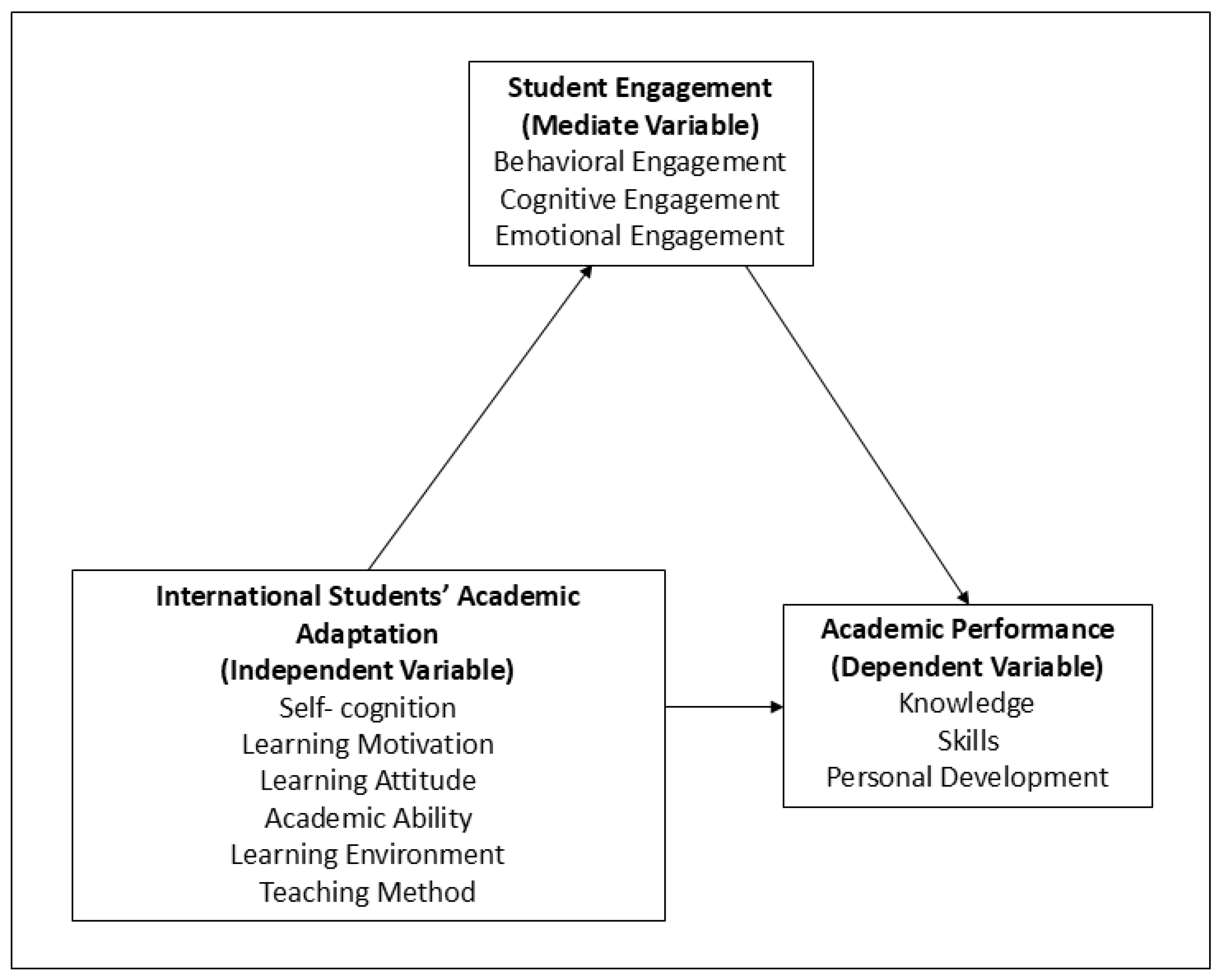

2.5.5. Conceptual Framework

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Measuring Instruments

3.2. Procedure and Respondent

4. Results

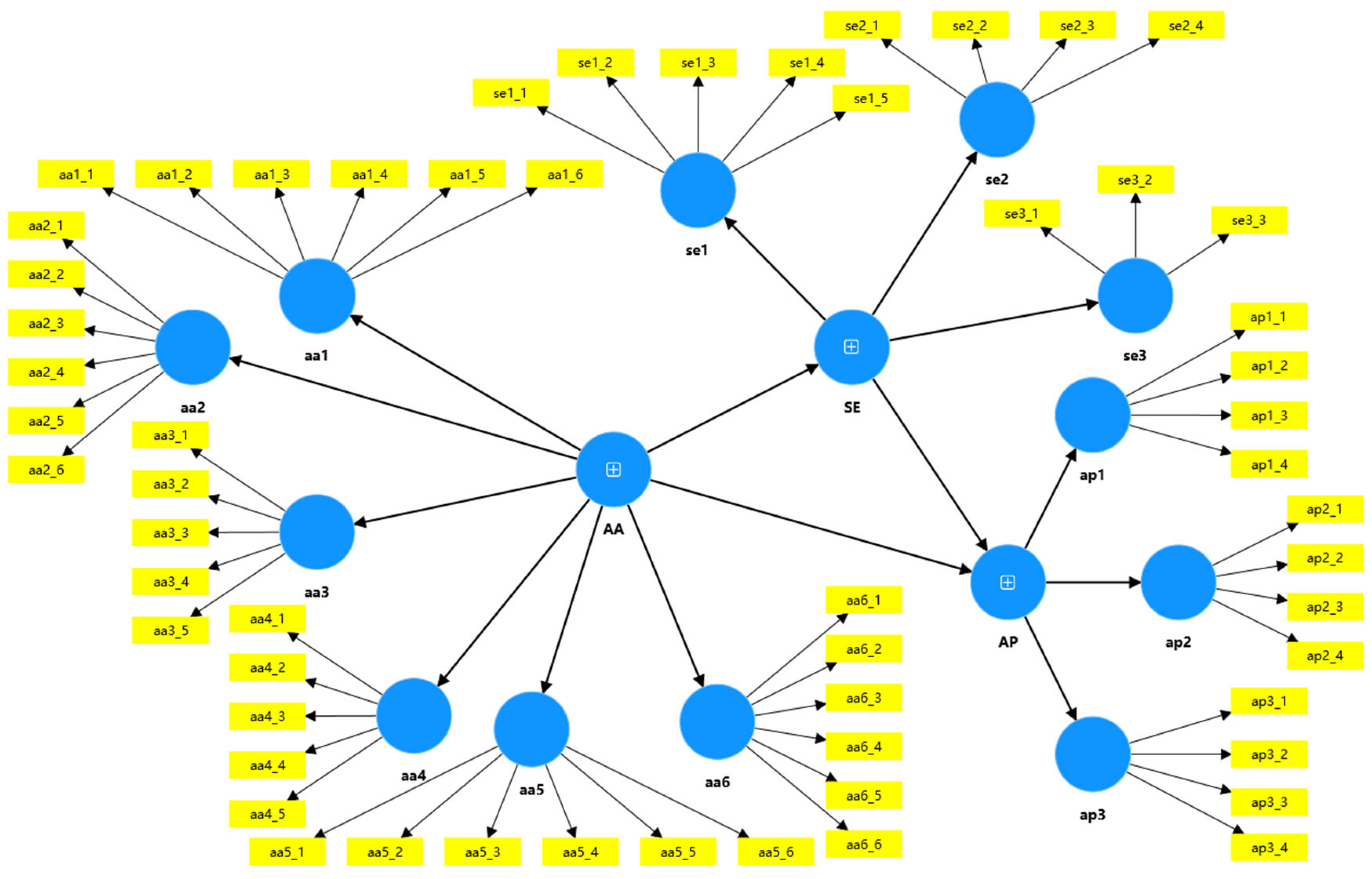

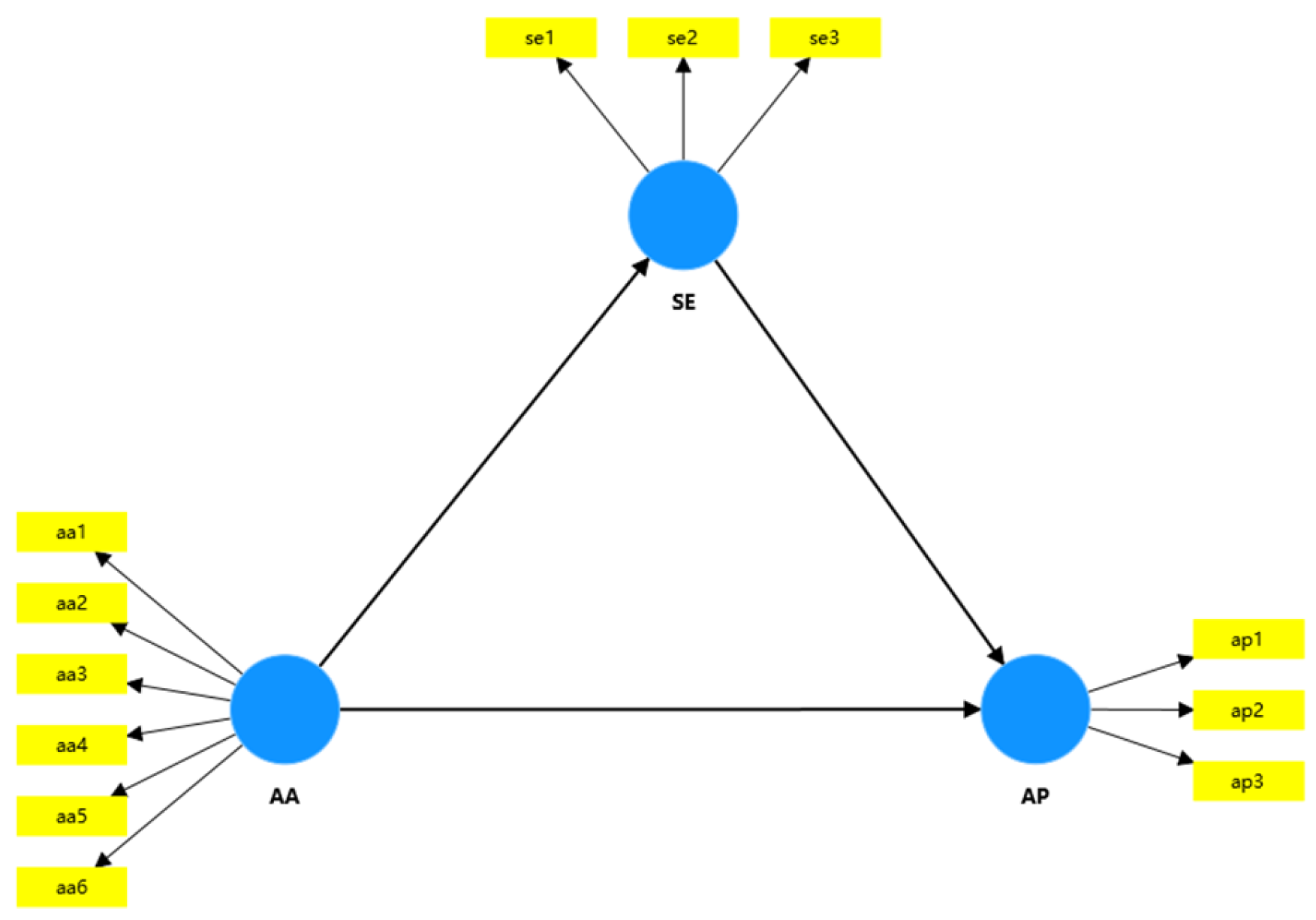

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Model

4.3. Research Hypotheses

4.3.1. Is There Any Significant Influence of Academic Adaptation on Academic Performance Among International Students in China?

4.3.2. Is There Any Significant Influence of Academic Adaptation on Student Engagement Among International Students in China?

4.3.3. Is There Any Significant Influence of Student Engagement on Academic Performance Among International Students in China?

4.3.4. Is There Any Significant Mediating Influence of Student Engagement on the Relationship Between International Students’ Academic Adaptation and Academic Performance Among International Students in China?

5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Altbach, P.G.; Knight, J. The internationalization of higher education: Motivations and realities. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2007, 11, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczewski, M.; Alon, I. Language and communication in international students’ adaptation: A bibliometric and content analysis review. High. Educ. 2023, 85, 1235–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loes, C.; Pascarella, E.; Umbach, P. Effects of diversity experiences on critical thinking skills: Who benefits? J. High. Educ. 2012, 83, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossman, J.E.; Clarke, M. International experience and graduate employability: Stakeholder perceptions on the connection. High. Educ. 2010, 59, 599–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deardorff, D.K. Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2006, 10, 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienties, B.; Beausaert, S.; Grohnert, T.; Niemantsverdriet, S.; Kommers, P. Understanding academic performance of international students: The role of ethnicity, academic and social integration. High. Educ. 2012, 63, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J.A.; Blumenfeld, P.C.; Paris, A.H. School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004, 74, 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Project Atlas Infographics. 2018. Available online: https://www.iie.org/research-initiatives/project-atlas/explore-global-data/ (accessed on 11 February 2024).

- Al-Tameemi, R.A.N.; Johnson, C.; Gitay, R.; Abdel-Salam, A.S.G.; Al Hazaa, K.; BenSaid, A.; Romanowski, M.H. Determinants of poor academic performance among undergraduate students—A systematic literature review. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2023, 4, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Horta, H.; Yuen, M. International medical students’ perspectives on factors affecting their academic success in China: A qualitative study. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, J. Analysis Report on Academic Performance of International Students in China—Taking the 2017 Autumn Semester Results of XX University’s 2017 International Students as an Example. Int. Public Relat. 2020, 214–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crede, M.; Niehorster, S. Adjustment to college as measured by the student adaptation to college questionnaire: A quantitative review of its structure and relationships with correlates and consequences. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 24, 133–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M.S. International students in English-speaking universities: Adjustment factors. J. Res. Int. Educ. 2006, 5, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G. Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Undergraduates Studying in China. Doctor’s Thesis, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2011. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CDFD0911&filename=1011129211.nh (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Dunn, J.W. Academic Adjustment of Chinese Graduate Students in United States Institutions of Higher Education. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, P.E. Theorizing student engagement in higher education. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2014, 40, 1005–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinto, V. Leaving College: Rethinking the Causes and Cures of Student Attrition, 2nd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.Q.; Wu, F.; Sun, Y.L.; Zhou, Q.; Zuo, Y.Y. Cross-cultural adaptation and management strategies of Vietnamese students: A survey of Vietnamese students in Yunnan University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Value Eng. 2017, 31, 249–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Gong, X. Investigation and analysis of cross-cultural academic adaptation of African students studying in China. Educ. Rev. 2018, 9, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. Master’s Degree in Education Quality Research for International Students in China from the Perspective of Learning Engagement. Master’s Dissertation, Jilin University, Jilin, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Suleiman, I.B.; Okunade, O.A.; Dada, E.G.; Ezeanya, U.C. Key factors influencing students’ academic performance. J. Electr. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2024, 11, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, T.T.; Gibson, C.; Rankin, S. Defining and measuring academic success. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2015, 20, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.; Preckel, F. Variables associated with achievement in higher education: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 565–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.X.; Tienda, M. Test scores, class rank and college performance: Lessons for broadening access and promoting success. Rass. Ital. Di Sociol. 2012, 53, 199–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuncel, N.R.; Hezlett, S.A. Standardized tests predict graduate students’ success. Science 2007, 315, 1080–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascarella, E.T.; Terenzini, P.T. How College Affects Students: A Third Decade of Research; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, G.; Wang, X. An Empirical Study on the Impact of High School Academic Preparation on College Students’ Academic Performance. Jiangsu High. Educ. 2023, 10, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Q. Master’s Degree in Empirical Research on the Relationship Between Undergraduate Students’ Learning Engagement and Academic Performance Based on CCSS Survey. Master’s Dissertation, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tinto, V. Dropout from higher education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Rev. Educ. Res. 1975, 45, 89–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.W.; Siryk, B. Measuring adjustment to college. J. Couns. Psychol. 1984, 31, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W. Study on the Academic Adaptability of ASEAN International Graduate Students in China Under the Background of Convergent Management. Master’s Thesis, Guangxi University, Nanning, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D. The Cross-cultural academic adaptation of Chinese students in an American university: Academic challenges, influential factors and coping strategies. Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 5, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Shan, X. A Qualitative Study on Chinese Postgraduate Students’ Learning Experiences in Australia. In Proceedings of the AARE 2006 International Education Research Conference, Adelaide, Australia, 26–30 November 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Finn, J.D. Withdrawing from School. Rev. Educ. Res. 1989, 59, 117–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascarella, E.T.; Seifert, T.A.; Blaich, C. How Effective are the NSSE Benchmarks in Predicting Important Educational Outcomes? Change Mag. High. Learn. 2010, 42, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Perspective Transformation. Adult Educ. Q. 1978, 28, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.W.; Cranton, P. A theory in progress? Issues in transformative learning theory. Eur. J. Res. Educ. Learn. Adults 2013, 4, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumi–Yeboah, A.; James, W. Transformative learning experiences of international graduate students from Asian countries. J. Transform. Educ. 2014, 12, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienties, B.; Luchoomun, D.; Tempelaar, D. Academic and social integration of Master students: A cross-institutional comparison between Dutch and international students. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2014, 51, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Abraham, C.; Bond, R. Psychological correlates of university students’ academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 138, 353–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Rahman, M.S.; Li, X. The effects of academic adaptation on depression of international students in China: A case study on South Asian students of TCSOL teacher program. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2023, 94, 101804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y. Academic adaptation of international students in the Chinese higher education environment: A case study with mixed methods. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2024, 103, 102082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhard, J.G. International students’ adjustment problems and behaviors. J. Int. Stud. 2012, 2, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, R.; Holliman, A.; Martin, A. Adaptability, engagement, and academic achievement at university. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 37, 632–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.J.; Nejad, H.; Colmar, S.; Liem, G.A.D. Adaptability: Conceptual and Empirical Perspectives on Responses to Change, Novelty and Uncertainty. Aust. J. Guid. Couns. 2012, 22, 58–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliman, A.J.; Martin, A.J.; Collie, R.J. Adaptability, engagement, and degree completion: A longitudinal investigation of university students. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 38, 785–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuh, G.D.; Kinzie, J.; Schuh, J.H.; Whitt, E.J. Fostering student success in hard times. Change Mag. High. Learn. 2011, 43, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClenney, K.; Marti, C.N.; Adkins, C. Student Engagement and Student Outcomes: Key Findings from CCSSE Validation Research; Community college survey of student engagement: Austin, TX, USA, 2012; pp. 1–6. Available online: http://www.ccsse.org/center (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Wang, Y. The Research on the Development of The College Student Engagement Questionnaire—Based on the Data Analysis of “National College Students’ Learning Situation Investigation”. J. Hebei Univ. Sci. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2015, 3, 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Boulton, C.A.; Hughes, E.; Kent, C.; Smith, J.R.; Williams, H.T.P. Student engagement and wellbeing over time at a higher education institution. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z. Modelling Undergraduate Student Engagement in China. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2019, 9, 1501–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qin, X. Research on the relationship between students’ learning engagement and learning gains in the Top-notch Plan. Jiangsu High. Educ. 2019, 12, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galve-González, C.; Bernardo, A.B.; Núnez, J.C. Trayectorias académicas: El papel del compromiso como mediador en la decisión de abandono o permanencia universitaria. Rev. Psicodidáctica 2024, 29, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godsk, M.; Møller, K.L. Engaging students in higher education with educational technology. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 2941–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Zhang, W.; Li, D.; Yu, C.; Dai, W. The relationship between gratitude and academic achievement of junior high school students: The intermediary role of learning input. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2010, 6, 598–605. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Q.; Zhang, Q. The influence of academic self-efficacy on university students’ academic performance: The mediating effect of academic engagement. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Sun, C.; Wang, Y. The mediating role of learning engagement on learning gains of international students in Chinese higher education institutions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adom, D.; Hussein, E.K.; Agyem, J.A. Theoretical and conceptual framework: Mandatory ingredients of a quality research. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2018, 7, 438–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J. Partial least squares path modeling. In Advanced Methods for Modeling Markets; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate data analysis: An overview. Int. Encycl. Stat. Sci. 2011, 904–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, T.; Liu, Y.; Yi, Y.; Zhang, Y. A review on the research of learning adjustment of undergraduates and educational measures. J. Southwest Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2010, 36, 135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Kuh, G.D. The national survey of student engagement: Conceptual and empirical foundations. New Dir. Institutional Res. 2009, 141, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, X.; Bikorimana, E. The impact of Academic adaptation to learning engagement among international postgraduates in China. Jiangsu High. Educ. 2022, 38, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. A study on the conflict manifestations and coping strategies of cross-cultural adaptation of ASEAN international students in China. Teach. Educ. (High. Educ. Forum) 2016, 21, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Tinto, V. Reflections: Rethinking engagement and student persistence. Stud. Success 2023, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.J.; Levesque-Bristol, C.; Yough, M. International students’ self-determined motivation, beliefs about classroom assessment, learning strategies, and academic adjustment in higher education. High. Educ. 2021, 81, 1215–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Description | Frequency (n = 427) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 225 | 52.69% |

| Female | 202 | 47.31% |

| Age | ||

| 19–20 | 147 | 34.43% |

| 21–22 | 175 | 40.98% |

| 23–24 | 82 | 19.20% |

| 25–26 | 23 | 5.39% |

| Nationality | ||

| India | 47 | 11.01% |

| South Korea | 47 | 11.01% |

| Pakistan | 21 | 4.92% |

| Thailand | 50 | 11.71% |

| Bangladesh | 15 | 3.51% |

| Tanzania | 10 | 2.34% |

| Ghana | 12 | 2.81% |

| Indonesia | 41 | 9.6% |

| Nigeria | 16 | 3.75% |

| Russia | 29 | 6.79% |

| Malaysia | 26 | 6.09% |

| Kenya | 10 | 2.34% |

| Vietnam | 46 | 10.77% |

| Others | 57 | 13.35% |

| Major Category | ||

| Engineering | 117 | 27.40% |

| Western Medicine | 32 | 7.49% |

| Management | 62 | 14.52% |

| Economics | 54 | 12.65% |

| Chinese language | 77 | 18.03% |

| Chinese Medicine | 25 | 5.85% |

| Science | 42 | 9.84% |

| Others | 18 | 4.22% |

| Chinese proficiency | ||

| HSK3 | 80 | 18.74% |

| HSK4 | 267 | 62.53% |

| HSK5 | 78 | 18.27% |

| HSK6 | 2 | 0.47% |

| Medium of Instruction | ||

| Chinese | 272 | 63.7% |

| English | 105 | 24.56% |

| Bilingual | 50 | 11.7% |

| Construct | Item | Outer Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic Adaptation | 0.984 | 0.985 | 0.657 | ||

| Self-perception | SB01 | 0.878 | 0.926 | 0.927 | 0.732 |

| SB02 | 0.852 | ||||

| SB03 | 0.902 | ||||

| SB04 | 0.814 | ||||

| SB05 | 0.825 | ||||

| SB06 | 0.826 | ||||

| Learning motivation | SB07 | 0.726 | 0.894 | 0.903 | 0.655 |

| SB08 | 0.860 | ||||

| SB09 | 0.698 | ||||

| SB10 | 0.842 | ||||

| SB11 | 0.858 | ||||

| SB12 | 0.817 | ||||

| Learning attitude | SB13 | 0.808 | 0.898 | 0.900 | 0.712 |

| SB14 | 0.804 | ||||

| SB15 | 0.868 | ||||

| SB16 | 0.889 | ||||

| SB17 | 0.825 | ||||

| Academic ability | SB18 | 0.870 | 0.944 | 0.945 | 0.816 |

| SB19 | 0.896 | ||||

| SB20 | 0.938 | ||||

| SB21 | 0.901 | ||||

| SB22 | 0.893 | ||||

| Learning environment | SB23 | 0.881 | 0.958 | 0.958 | 0.825 |

| SB24 | 0.931 | ||||

| SB25 | 0.918 | ||||

| SB26 | 0.922 | ||||

| SB27 | 0.913 | ||||

| SB28 | 0.865 | ||||

| Teaching method | SB29 | 0.922 | 0.954 | 0.957 | 0.815 |

| SB30 | 0.934 | ||||

| SB31 | 0.935 | ||||

| SB32 | 0.849 | ||||

| SB33 | 0.826 | ||||

| SB34 | 0.923 | ||||

| Student Engagement | 0.967 | 0.968 | 0.735 | ||

| Behavioral engagement | SC01 | 0.904 | 0.912 | 0.915 | 0.742 |

| SC02 | 0.813 | ||||

| SC03 | 0.889 | ||||

| SC04 | 0.807 | ||||

| SC05 | 0.860 | ||||

| Cognitive engagement | SC06 | 0.906 | 0.944 | 0.945 | 0.900 |

| SC07 | 0.916 | ||||

| SC08 | 0.922 | ||||

| SC09 | 0.915 | ||||

| Emotional engagement | SC10 | 0.942 | 0.938 | 0.938 | 0.842 |

| SC11 | 0.959 | ||||

| SC12 | 0.938 | ||||

| Academic Performance | 0.958 | 0.959 | 0.687 | ||

| Knowledge | SD01 | 0.884 | 0.908 | 0.909 | 0.784 |

| SD02 | 0.891 | ||||

| SD03 | 0.892 | ||||

| SD04 | 0.853 | ||||

| Skills | SD05 | 0.861 | 0.927 | 0.927 | 0.820 |

| SD06 | 0.912 | ||||

| SD07 | 0.922 | ||||

| SD08 | 0.915 | ||||

| Personal development | SD09 | 0.908 | 0.896 | 0.899 | 0.763 |

| SD10 | 0.892 | ||||

| SD11 | 0.866 | ||||

| SD12 | 0.809 | ||||

| Construct | Item | Item Parcel | Outer Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic Adaptation | SB01-06 | aa1 | 0.927 | 0.969 | 0.969 | 0.865 |

| SB07-12 | aa2 | 0.906 | ||||

| SB13-17 | aa3 | 0.925 | ||||

| SB18-22 | aa 4 | 0.933 | ||||

| SB23-28 | aa5 | 0.939 | ||||

| SB29-34 | aa6 | 0.950 | ||||

| Student Engagement | SC01-05 | se1 | 0.944 | 0.947 | 0.947 | 0.904 |

| SC06-09 | se2 | 0.957 | ||||

| SC10-12 | se3 | 0.952 | ||||

| Academic Performance | SD01-04 | ap1 | 0.924 | 0.927 | 0.928 | 0.873 |

| SD05-08 | ap2 | 0.930 | ||||

| SV09-12 | ap3 | 0.949 |

| Academic Adaptation | Academic Performance | Student Engagement | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academic Ability | 0.933 | 0.816 | 0.885 |

| Behavioral Engagement | 0.875 | 0.805 | 0.944 |

| Cognitive Engagement | 0.845 | 0.800 | 0.957 |

| Emotional Engagement | 0.873 | 0.822 | 0.952 |

| Knowledge | 0.835 | 0.924 | 0.796 |

| Learning Attitude | 0.925 | 0.834 | 0.867 |

| Learning Environment | 0.939 | 0.835 | 0.837 |

| Learning Motivation | 0.906 | 0.856 | 0.793 |

| Personal development | 0.858 | 0.949 | 0.809 |

| Self-perception | 0.927 | 0.869 | 0.807 |

| Skills | 0.843 | 0.930 | 0.781 |

| Teaching Method | 0.950 | 0.839 | 0.883 |

| Academic Adaptation | Academic Performance | Student Engagement | |

| Academic Adaptation | 0.930 | ||

| Academic Performance | 0.904 | 0.935 | |

| Student Engagement | 0.909 | 0.851 | 0.951 |

| Academic Adaptation | Academic Performance | Student Engagement | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academic Adaptation | 5.776 | 1.000 | |

| Academic Performance | |||

| Student Engagement | 5.776 |

| R-Square | R-Square Adjusted | Level | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academic Performance | 0.823 | 0.822 | High |

| Student Engagement | 0.827 | 0.826 | High |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | β Value | SD | T Statistics | p Values | CI95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Academic Adaptation -> Academic Performance | 0.754 | 0.059 | 12.741 | 0.000 | [0.635, 0.865] |

| H2 | Academic Adaptation -> Student Engagement | 0.909 | 0.010 | 95.550 | 0.000 | [0.889, 0.926] |

| H3 | Student Engagement -> Academic Performance | 0.166 | 0.062 | 2.688 | 0.007 | [0.049, 0.285] |

| H4 | Academic Adaptation -> Student Engagement -> Academic Performance | 0.151 | 0.056 | 2.701 | 0.007 | [0.045, 0.259] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Ismail, A. Academic Adaptation and Performance Among International Students in China: The Mediating Role of Student Engagement. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11256. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411256

Liu Y, Ismail A. Academic Adaptation and Performance Among International Students in China: The Mediating Role of Student Engagement. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11256. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411256

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yu, and Aziah Ismail. 2025. "Academic Adaptation and Performance Among International Students in China: The Mediating Role of Student Engagement" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11256. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411256

APA StyleLiu, Y., & Ismail, A. (2025). Academic Adaptation and Performance Among International Students in China: The Mediating Role of Student Engagement. Sustainability, 17(24), 11256. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411256