Motivations for Slow Fashion Consumption Among Zennials: An Exploratory Australian Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Significance of Studying Zennials

2. Literature Review

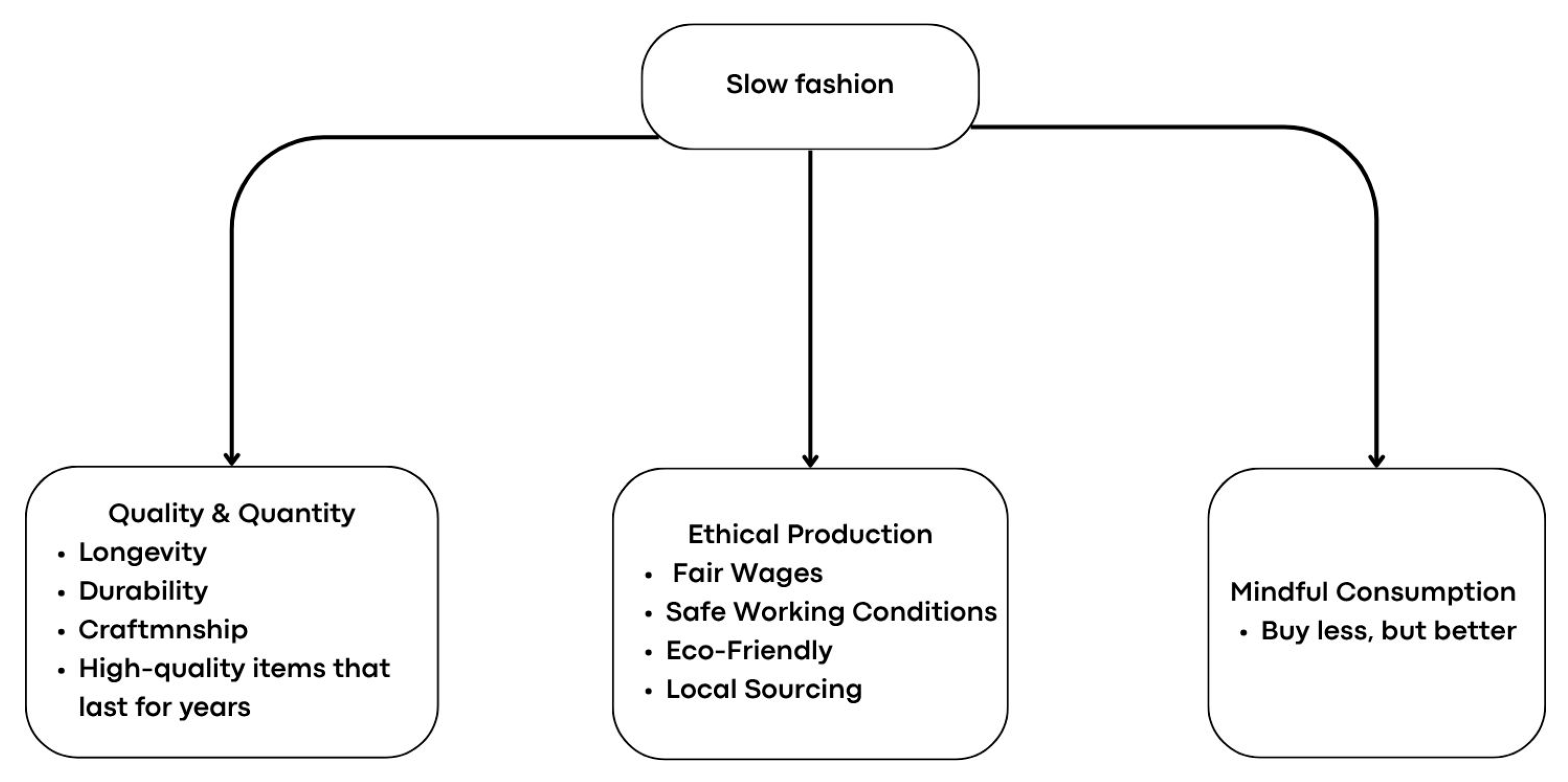

2.1. Defining Slow Fashion

2.2. Slow Fashion vs. Fast Fashion

2.3. Zennial Slow Fashion Consumption

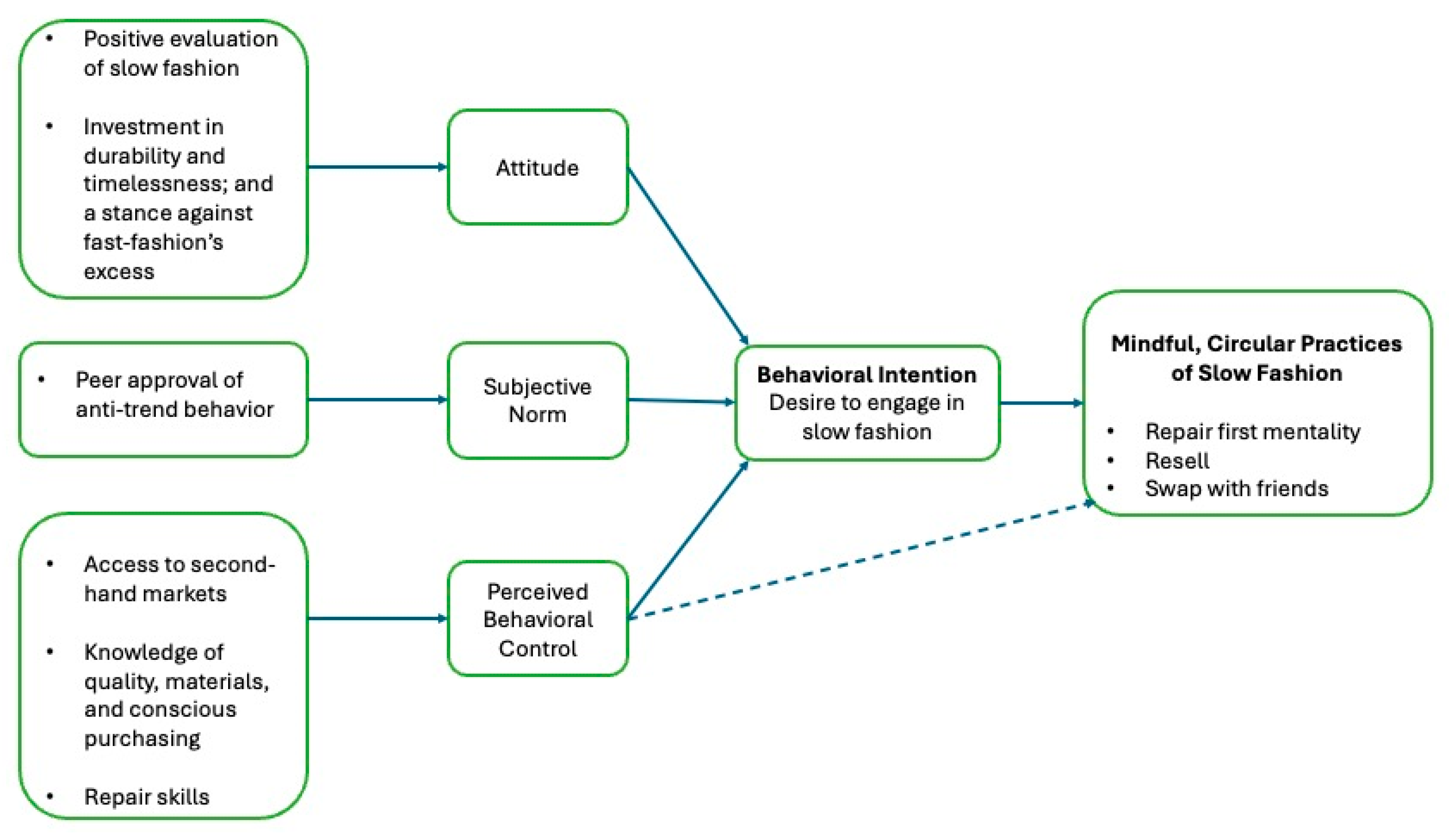

2.4. The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

2.4.1. Attitude Towards the Behavior

2.4.2. Subjective Norms

2.4.3. Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC)

3. Methodology

3.1. Materials and Methods

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Procedures

3.1.3. Measures

- What is your understanding of slow fashion?

- What are your key concerns about the fashion or clothing industry?

- Does certification on the clothing label mean anything to you?

- Do you trust the company’s ethical claims in production? If not, why?

- What type of clothing designs do you prefer and why?

- How do your peers or social media influence your clothing choices?

- Do recommendations from influencers or friends affect your purchasing decisions?

- What kinds of fashion brands do you buy from?

- What types of clothing items do you buy from this brand? Why?

- How often do you buy clothing?

- How would you describe your wardrobe?

- How often do you wear the clothes you bought?

- What do you do with clothing you no longer wear? Can you tell me about your unworn clothing, if you have any, and why?

3.1.4. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Attitude Towards Slow Fashion

4.1.1. Durability and Timelessness

4.1.2. Ethical Rejection of Fast Fashion’s Excess

4.2. Perceived Behavioral Control: Enabling Strategies

4.2.1. Leveraging the Second-Hand Economy

4.2.2. Knowledge and Repair Skills

4.3. Subjective Norms: Peer Influence and Anti-Trend Culture

Anti-Trend Peer Culture

4.4. Behavioral Practice: Mindful and Circular Consumption

Repair and Recirculation

5. Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical and Policy Implications

5.2.1. Implications for Business Models

5.2.2. Implications for Policy and Regulation

6. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behavior |

| PBC | Perceived Behavioral Control |

| Gen | Generation |

References

- Tiwari, S.; Shah, P.; Nainani, V. The Interplay of Fashion and Personal Identity: Exploring How Clothing Choices Reflect and Shape Personality. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2024, 13, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Wang, L.; Padhye, R. Textile Waste Management in Australia: A Review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2023, 18, 200154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Fashion Council and Consortium. Seamless Scheme Design Summary Report. May 2023. Available online: https://ausfashioncouncil.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Seamless-Scheme-Design-Summary-Report.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Domingos, M.; Vale, V.T.; Faria, S. Slow Fashion Consumer Behavior: A Literature Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhissi, M.; Hamouda, M. Investigating Consumers’ Slow Fashion Purchase Decision: Role of Lack of Information and Confusion. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2025, 37, 575–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Weder, F. Framing Sustainable Fashion Concepts on Social Media. An Analysis of #slowfashionaustralia Instagram Posts and Post-COVID Visions of the Future. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K. Slow Fashion: An Invitation for Systems Change. Fash. Pract. 2010, 2, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes De Oliveira, L.; Miranda, F.G.; De Paula Dias, M.A. Sustainable Practices in Slow and Fast Fashion Stores: What Does the Customer Perceive? Clean. Eng. Technol. 2022, 6, 100413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solino, L.J.S.; Teixeira, B.M.D.L.; Dantas, Í.J.D.M. Sustainability in Fashion: A Systematic Literature Review on Slow Fashion. Int. J. Innov. Educ. Res. 2020, 8, 164–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E.A.; Litchfield, C.A.; Le Busque, B. Barriers, Brands and Consumer Knowledge: Slow Fashion in an Australian Context. Cloth. Cult. 2021, 8, 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegethesan, K.; Sneddon, J.N.; Soutar, G.N. Young Australian Consumers’ Preferences for Fashion Apparel Attributes. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2012, 16, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manley, A.; Seock, Y.; Shin, J. Exploring the Perceptions and Motivations of Gen Z and Millennials toward Sustainable Clothing. Fam. Consum Sci. Res. J. 2023, 51, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WGSN. Zennials: The In-Between Generation. WGSN Insight, Article No. 87486. Available online: https://www.wgsn.com/insight/article/87486 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- da Silva, S.; de Sousa Gomes, C. Barriers to Slow Fashion: A Comparison Between the Perceptions of Generation X, Y and Z. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Catolica Portuguesa, Lisbon, Portugal, 2023. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global; Order No. 31518034. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/barriers-slow-fashion-comparison-between/docview/3122647916/se-2 (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Charlton, E. The Cost of Living is a Top Concern for Gen Z and Millennials. World Economic Forum. 19 May 2023. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2023/05/gen-z-millennials-work-cost-living/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Gen Unison. Generation Names and Years. Available online: https://genunison.com/generation-years/generation-names/ (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- AlphaBeta Advisors. Afterpay Next Gen Index: Millennials and Gen Z in Australia. Afterpay Australia. 2021. Available online: https://afterpay-newsroom.yourcreative.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Afterpay_Web_report_AUS_vF-1-2.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Brand, B.M.; Rausch, T.M.; Brandel, J. The Importance of Sustainability Aspects When Purchasing Online: Comparing Generation X and Generation Z. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WGSN. Generational Futures: Fringe Demographics. WGSN Insight. Available online: https://www.wgsn.com/auth/login?lang=en&r=%2Finsight%2Farticle%2F66a7786656656d48f7d32396%3Flang%3Den (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- McKinsey. What Is Gen Z? McKinsey Explainers. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/mckinsey-explainers/what-is-gen-z (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Climate Council. New Poll Shows Aussies Back Strong Climate Action, as Unnatural Disasters Dent Productivity. Climate Council Media Release. 8 August 2025. Available online: https://www.climatecouncil.org.au/resources/new-poll-shows-aussies-back-strong-climate-action-as-unnatural-disasters-dent-productivity (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Chi, T.; Gerard, J.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Y. A Study of U.S. Consumers’ Intention to Purchase Slow Fashion Apparel: Understanding the Key Determinants. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2021, 14, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duh, H.I.; Yu, H.; Venter De Villiers, M.; Steffek, V.; Shao, D. Determinants of Young Adults’ Slow Fashion Attitudes and Idea Adoption Intentions in Canada, China and South Africa. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2024, 20, 3252–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprianingsih, A.; Fachira, I.; Setiawan, M.; Debby, T.; Desiana, N.; Lathifan, S.A.N. Slow Fashion Purchase Intention Drivers: An Indonesian Study. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2023, 27, 632–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, C. Sustainable fashion: To define, or not to define, that is not the question. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2023, 19, 2261342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, D.G.K.; Weerasinghe, D. Towards Circular Economy in Fashion: Review of Strategies, Barriers and Enablers. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2022, 2, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElShihy, D.; Awaad, S. Leveraging social media for sustainable fashion: How brand and user-generated content influence Gen Z’s purchase intentions. Future Bus. J. 2025, 11, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey & Company. The Price is not Right: Gen Z’s Sustainable-Fashion Conundrum. McKinsey. 2023. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/email/genz/2023/06/2023-06-06b.html (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Bick, R.; Halsey, E.; Ekenga, C.C. The Global Environmental Injustice of Fast Fashion. Environ. Health 2018, 17, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, S.; Jin, B. A Theoretical Investigation of Slow Fashion: Sustainable Future of the Apparel Industry. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, H. SLOW + FASHION—An Oxymoron—Or a Promise for the Future…? Fash. Theory 2008, 12, 427–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrini, C. Slow Food: The Case for Taste; McCuaig, W., Translator; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; Originally published as Slow Food: Le Ragioni del Gusto; Gius. Laterza & Figli: Bari, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pookulangara, S.; Shephard, A. Slow Fashion Movement: Understanding Consumer Perceptions—An Exploratory Study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2013, 20, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Jin, B. From Quantity to Quality: Understanding Slow Fashion Consumers for Sustainability and Consumer Education. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, K.; Hassi, L. Emerging Design Strategies in Sustainable Production and Consumption of Textiles and Clothing. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1876–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K. Durability, Fashion, Sustainability: The Processes and Practices of Use. Fash. Pract. 2012, 4, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, K.; Johnson Jorgensen, J. Millennial Perceptions of Fast Fashion and Second-Hand Clothing: An Exploration of Clothing Preferences Using Q Methodology. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazanec, J.; Harantová, V. Gen Z and Their Sustainable Shopping Behavior in the Second-Hand Clothing Segment: Case Study of the Slovak Republic. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devetak, T.; Pavko Čuden, A. Sustainable Fashion in Slovenia: Circular Economy Strategies, Design Processes, and Regional Innovation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WGSN. Brand Strategy: Marketing to Zennials. Available online: https://www.wgsn.com/auth/login?lang=en&r=%2Finsight%2Farticle%2F87486%3Flang%3Den (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- News Medical Life Sciences. Available online: https://www.news-medical.net/news/20240305/Australian-Gen-Z-people-have-major-concerns-about-climate-change-research-shows.aspx (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Welch, K.; Gen, Z. Millennials Lose Sustainability Cred, Turn to Ultra-Fast Fashion Homewares Giants Temu. Mi3. 25 March 2025. Available online: https://www.mi-3.com.au/25-03-2025/gen-z-millennials-lose-sustainability-cred-turn-ultra-fast-fashion-homewares-giants-temu (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Income: Household and Individual; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2021. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/income-household-and-individual (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Statista. Gen Z and Global Users Top Social Media Usage in 2023. Statista. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1446950/gen-z-internet-users-social-media-use (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Sprout Social. Aussie Influencer Marketing in 2025. Sprout Blog. 27 March 2025. Available online: https://sproutsocial.com/insights/influencer-marketing-stats-australia (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Liu, A.; Baines, E.; Ku, L. Slow Fashion Is Positively Linked to Consumers’ Well-Being: Evidence from an Online Questionnaire Study in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, S.; Jin, B. Sustainable Development of Slow Fashion Businesses: Customer Value Approach. Sustainability 2016, 8, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayza Gomez, V.; Islam, S.; Tan, C.S.L. Sustainable Fashion: Insights into Australian Millennials’ Purchasing Decisions. Sustain. Econ. 2025, 3, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badhwar, A.; Islam, S.; Tan, C.S.L.; Panwar, T.; Wigley, S.; Nayak, R. Unraveling Green Marketing and Greenwashing: A Systematic Review in the Context of the Fashion and Textiles Industry. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuzzaman, M.; Islam, M.; Mamun, M.A.A.; Rayyaan, R.; Sowrov, K.; Islam, S.; Sayem, A.S.M. Fashion and Textile Waste Management in the Circular Economy: A Systematic Review. Clean. Waste Syst. 2025, 11, 100268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clothing Stewardship Australia Ltd. Seamless Clothing Stewardship Scheme. Available online: https://www.seamlessaustralia.com (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- European Commission. Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR): Durability and Repairability Standards for Textiles. European Union. 2024. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Payne, A.; Jiang, X.; Street, P.; Leenders, M.; Nguyen, T.N.; Pervan, S.; Tan, C.S.L. Keeping Clothes Out of Landfill: A Landscape Study of Australian Consumer Practices; RMIT University: Melbourne, Australia, 2024; Available online: https://doi.org/10.25439/rmt.27092239.v1 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Swedish Government. Tax Reduction on Repair Services. Government of Sweden; 2017. Available online: https://www.government.se (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- ADEME. Repair Bonus: Financial Incentives for Textile Repairs. French Agency for Ecological Transition. 2023. Available online: https://www.ademe.fr (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Bauer, A.; Menrad, K. The Nexus between Moral Licensing and Behavioral Consistency: Is Organic Consumption a Door-Opener for Commitment to Climate Protection? Soc. Sci. J. 2023, 60, 665–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Principle | Description |

|---|---|

| Ethical Production | Built upon fair labor practices, safe working conditions, and equitable wages for all individuals involved in the supply chain, from raw material sourcing to final garment construction [7]. |

| Quality & Longevity | This principle combines superior craftsmanship, high-quality materials, and attention to detail with the goal of creating garments designed to last. The focus is on physical durability and timeless style, ensuring items remain strong and aesthetically appealing over extended periods, which discourages frequent replacement [7,32,34,35]. |

| Mindful Consumption | Involves consumers making more conscious, deliberate purchasing decisions, valuing their clothing, caring for it properly, and considering the full lifecycle of their garments to move away from impulsive buying [34]. |

| Sustainability | Relies on minimizing environmental impact by using eco-friendly materials, reducing water and energy consumption, minimizing waste and pollution, and considering biodiversity [36,37]. |

| Feature | Slow Fashion | Fast Fashion |

|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Offers an alternative to rapid consumerism, promoting sustainability, ethical labor, and long-lasting craftsmanship. | Promotes rapid consumerism and has detrimental environmental and ethical effects. |

| Key Consumer Appeal | Principles of durability, use of sustainable materials, and timeless styles | Speed and novelty. |

| Practical Manifestations | Practices include design for durability, use of sustainable or local materials, transparent supply chains, fair labor, small production runs, and repair services. | Mass production with a focus on rapid, trend-driven cycles. |

| Market Implication | Its appeal can be limited by the faster and cheaper options available in the resale market. | Its negative impacts have spurred the growth of alternatives like slow fashion. |

| N | Age | Gender | Education | Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25 | M | Cert III | Graphic Designer |

| 2 | 27 | F | Cert III | Early Childhood Educator |

| 3 | 23 | F | Bachelor’s Degree | Social Work Student |

| 4 | 29 | M | Bachelor’s Degree | Graphic Designer |

| 5 | 28 | F | Bachelor’s Degree | Digital Marketing Executive |

| 6 | 27 | F | Cert III | Interior Designer |

| 7 | 23 | F | Cert III | Interior Designer |

| 8 | 27 | M | High School | Graphic Designer |

| 9 | 26 | F | Bachelor’s Degree | Interior Designer |

| 10 | 28 | F | Bachelor’s Degree | Early Childhood Educator |

| 11 | 29 | M | Bachelor’s Degree | Designer (Creative/Open Design) |

| 12 | 26 | F | Master’s Degree | Digital Marketing Executive |

| 13 | 31 | F | Bachelor’s Degree | Yoga Instructor/Architect |

| 14 | 31 | F | High School | Entrepreneur |

| 15 | 23 | F | Bachelor’s Degree | Medical Student |

| 16 | 27 | F | Bachelor’s Degree | Traditional Chinese Medicine Practitioner |

| 17 | 24 | F | Bachelor’s Degree | Bachelor of Arts (English Language) Student |

| 18 | 26 | F | High School | Retail Manager |

| 19 | 30 | F | Cert III | Early Childhood Educator |

| 20 | 24 | F | Bachelor’s Degree | Medical Student |

| Overarching Theme | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|

| Attitude | Durability & Timelessness; Ethical Rejection of Fast Fashion’s Excess |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | Second-Hand Economy; Knowledge & Repair Skills |

| Subjective Norms | Anti-Trend Peer Culture |

| Behavioral Practice | Mindful and Circular Consumption |

| Target Area | Intervention Type (Policy/Business) | Recommendation Derived from Zennial Behavior | Cleaner Production/Circular Economy Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product Longevity | Policy/Regulatory (EPR) | Introduce minimum durability standards linked to mandatory repair guarantees (e.g., 5-year wear requirement or product-lifetime repair subsidies). | Mandates upstream Cleaner Production design changes; reduces waste volume. |

| Affordability/Access | Business/Policy (Incentives) | Subsidize repair/modification services; implement tax relief on second-hand goods. | Strengthens PBC for Zennials; accelerates Circular Economy loops and responsible consumption. |

| Transparency/Trust | Regulatory/Industry (Certification) | Establish independent, government-backed certification for supply chain ethics and material sourcing, moving beyond vague “green” claims. | Addresses greenwashing skepticism; reinforces Zennials’ demand for ethical production and minimizes risk exposure. |

| Waste Management | Policy/Regulatory (Logistics) | Investment in standardized, accessible public textile recycling and collection infrastructure separate from general waste streams. | Facilitates the final stages of the Zennial ‘mindful practice’ hierarchy (Figure 3), increasing material recovery. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khor, J.W.; Tan, C.S.L.; Islam, S. Motivations for Slow Fashion Consumption Among Zennials: An Exploratory Australian Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11253. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411253

Khor JW, Tan CSL, Islam S. Motivations for Slow Fashion Consumption Among Zennials: An Exploratory Australian Study. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11253. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411253

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhor, Jia Wei, Caroline Swee Lin Tan, and Saniyat Islam. 2025. "Motivations for Slow Fashion Consumption Among Zennials: An Exploratory Australian Study" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11253. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411253

APA StyleKhor, J. W., Tan, C. S. L., & Islam, S. (2025). Motivations for Slow Fashion Consumption Among Zennials: An Exploratory Australian Study. Sustainability, 17(24), 11253. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411253