Balancing Cultural Values and Energy Transition: A Multi-Criteria Approach Inspired by the New European Bauhaus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- 1.

- Identifying criteria to assess the compatibility and effectiveness of energy efficiency interventions in historic buildings.

- 2.

- Translate these criteria into the descriptors of evidence required for consolidated multi-criteria analysis methodologies.

- 3.

- Validate the criteria and descriptors by applying them to the retrofitting of a culturally significant building. Verify that they reflect the values of the NEB (sustainability, aesthetics and inclusion) and comply with current guidelines and standards.

2.1. Thematic Framework: Mapping of Recurring Topics

2.2. Decision-Making Criteria and Pairwise Comparison of Alternatives

| Topic | Criterion | Description | Performance Indicators (Unit/Scale) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | C1. Cultural compatibility and authenticity | Consistency of interventions with authenticity, integrity, reversibility, and legibility principles | Degree of reversibility; distinguishability of additions; impact on historical assemblies |

| C2. Typological and material coherence | Morphological, chromatic, and material compatibility of new elements | % of historic surfaces affected; morphological/chromatic coherence; type of anchoring (reversible/invasive) | |

| T2 | C3. “Efficiency first” principle | Priority to demand reduction before integrating RES | Share of demand reduction before RES; ratio between avoided demand and produced energy; extent of passive solutions |

| C4. Energy and climatic performance | Energy use, RES share, and GHG reduction | Energy use intensity (kWh/m2·year); RES coverage (%); avoided emissions (tCO2e/year); compliance with UNI EN 16798 | |

| C5. Environmental performance over the life cycle | Life cycle impact and resource efficiency | GWP A1–C4; recycled content; properties of deconstruction; simplified LCA (EN 15643/ISO 21929-1) | |

| T4 | C6. Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) | Comfort and health conditions for occupants and specific uses | Operative temperature; relative humidity; CO2 concentration; illuminance/UGR; noise levels; compliance with specific functional requirements (e.g., museum standards) |

| T3 | C7. Conservation risks and durability | Risk of physical or chemical damage due to retrofit | Risk of surface/interstitial condensation; hygroscopic incompatibility; thermo-hygrometric stress; service life planning (ISO 15686) |

| T4 | C8. Maintainability, management, and monitoring | Ease of maintenance and performance control | Accessibility for maintenance; expected time to repair (MTTR); presence of BMS/sub-metering; monitoring-reporting-verification plan |

| T5 | C9. Landscape and perceptual impact | Visual compatibility with landscape and context | Visibility from public viewpoints (viewshed/sightlines); coherence with skyline and context; minimisation of glare or visual clutter |

| T6 | C10. Safety and compliance | Fulfilment of legal and technical safety requirements | Compliance with fire safety, structural, and plant regulations; management of evacuation routes and protection of collections |

| C11. Cost and life cycle | Economic feasibility and long-term value | CAPEX and OPEX; life cycle cost (≥30 years); payback times; assessment of co-benefits (e.g., reduced degradation, improved usability) | |

| C12. Participation, acceptability, and cultural activation (NEB) | Social inclusion and creative engagement | Extent of co-design processes; stakeholder participation; survey of public perception; artistic/educational initiatives; inclusiveness and accessibility |

2.3. Evaluation of Project Alternatives

- (A)

- Goal: identification of the most balanced retrofit solution in terms of performance and conservation requirements;

- (B)

- (C)

- Alternatives: a baseline option (A0 = no intervention) and a set of alternative retrofit solutions conceived as combinable modules. Indeed, the design solutions are not mutually exclusive; the AHP compares a small number of bundles of measures (including the baseline) that were pre-defined to reflect realistic design scenarios and conservation constraints. This allows the assessment to capture both synergies and trade-offs among modules while keeping the decision space manageable.

- (1)

- construction of pairwise comparison matrices for criteria and alternatives;

- (2)

- calculation of eigenvectors to derive weights;

- (3)

- consistency check (CR < 0.1) to validate expert judgments [59];

- (4)

- sensitivity analysis of criterion weights (±10–20%) to test the robustness of the final ranking.

3. Framework Validation on a Heritage Retrofit Case Study

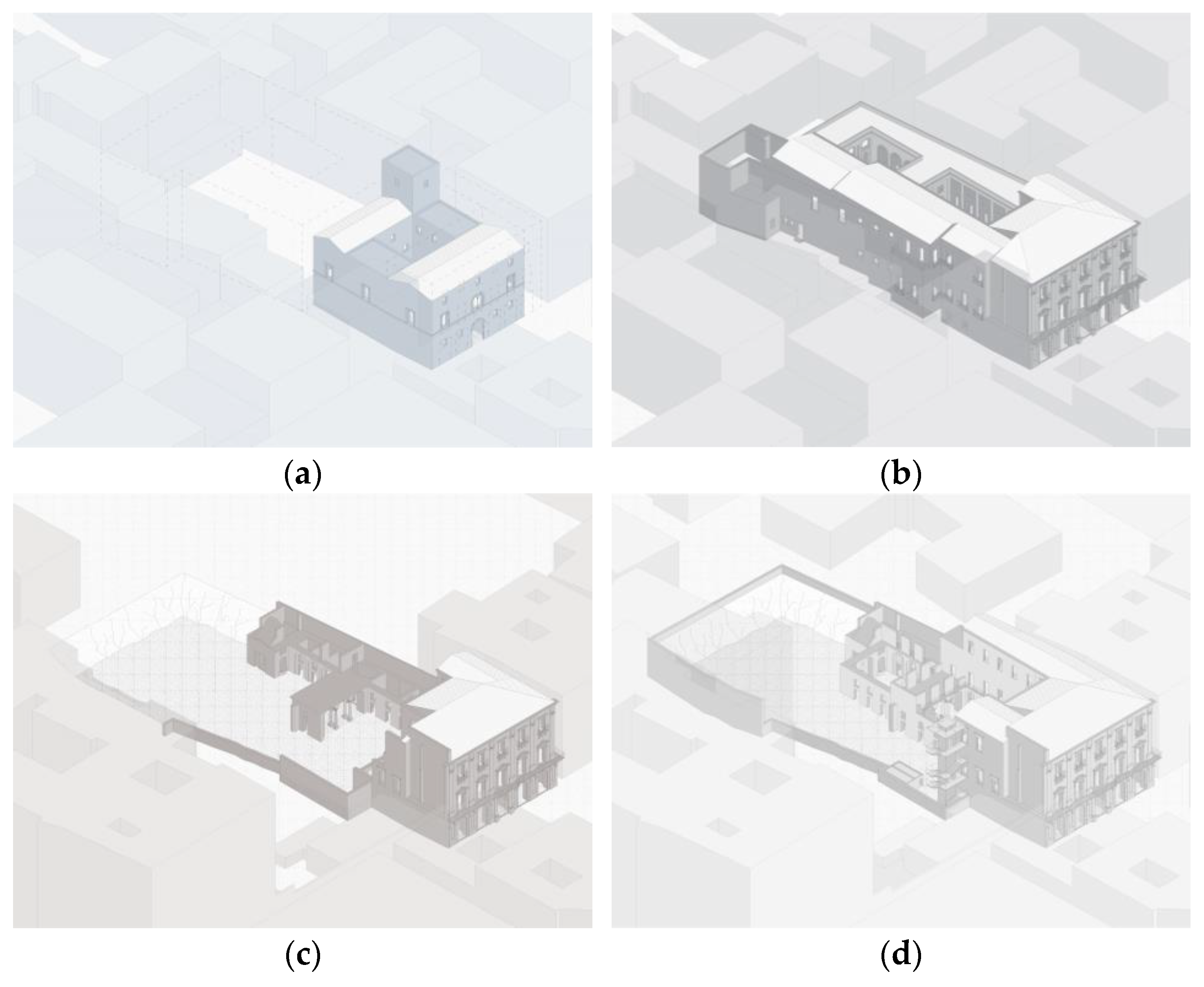

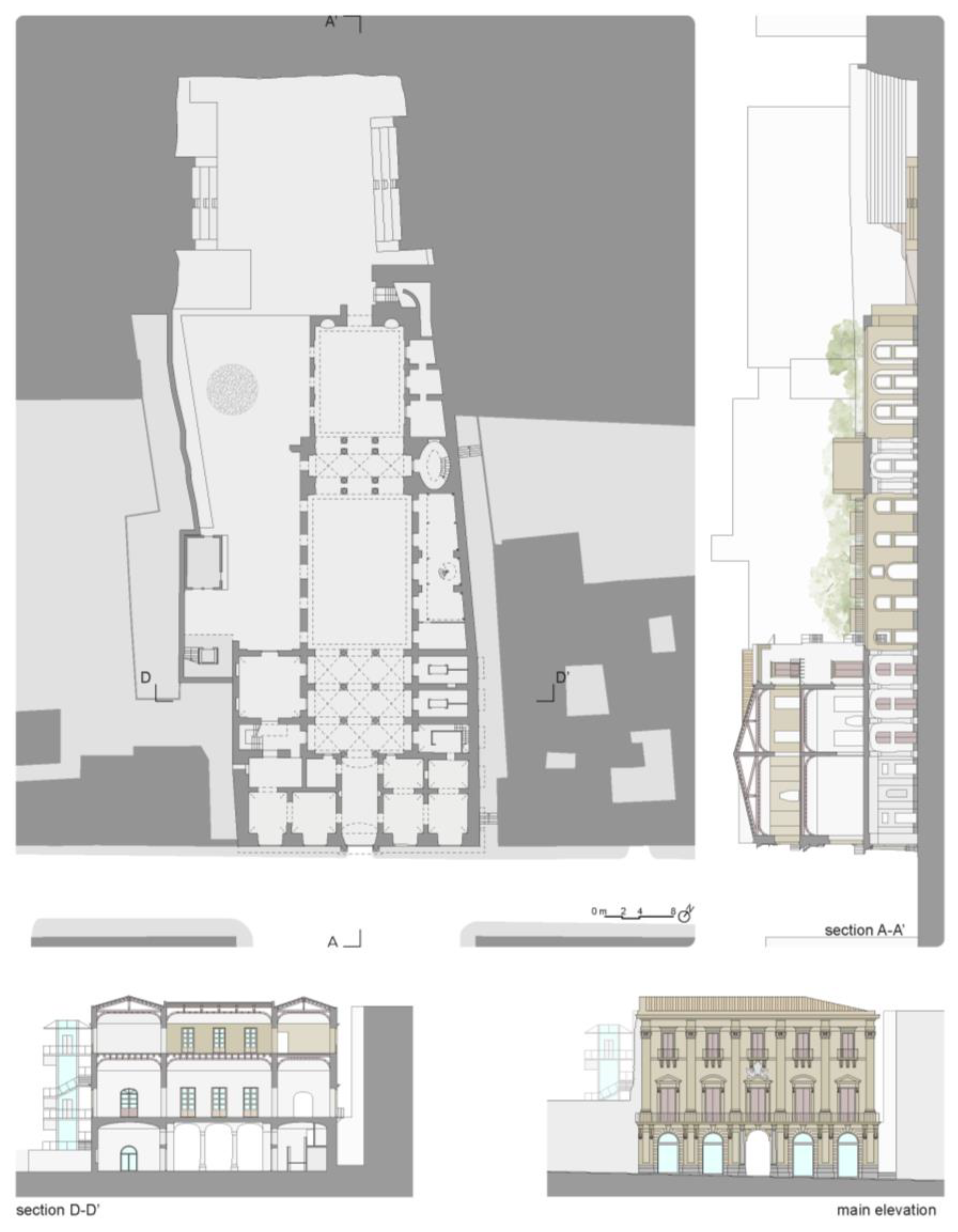

3.1. Belmonte-Riso Palace

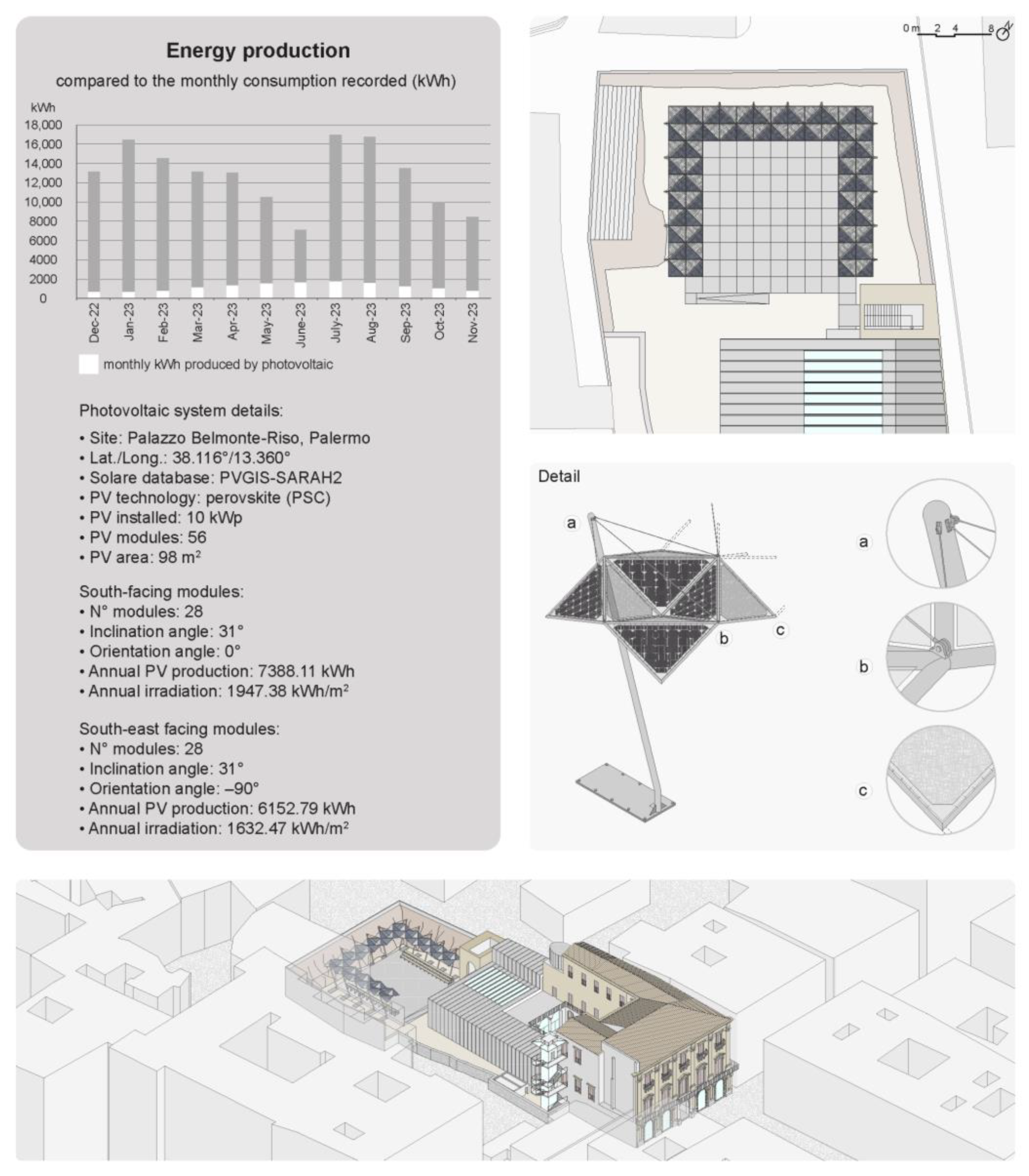

- energy production from renewable and clean sources through photovoltaic systems;

- energy savings of 30% with reference to current consumption, out of which 25% through efficiency improvements in heating and lighting systems, building management systems (BMS) and fixtures, and the remaining 5% through renewable energy production.

3.2. Energy Demand Analysis

- Fan coils with a chiller located in the technical room;

- VRF system with an outdoor unit located on the first-floor terrace and indoor units installed on the first and second floors of the east wing of the building.

- Heating period from 1 December 2022 to 31 April 2023;

- Cooling period from 1 May 2023 to 30 November 2023.

3.3. Design Hypotheses

- Module 1 (M1)—Smart Cultural Space for Renewable Integration: M1 introduces a lightweight canopy inspired by origami geometries, designed to host artistic performances in the museum courtyard. Its micro-perforated membrane ensures solar control and integrates innovative perovskite PV cells (PSC), achieving an estimated annual production of ~13,540 kWh [45], equivalent to 9% of current electricity demand. Beyond energy contribution, this module raises issues of visual compatibility (C9) and material reversibility (C1–C2), while supporting cultural activation (C12);

- Module 2 (M2)—Smart Playground for Educational Activation: M2 proposes interactive installations that combine art and technology to raise public awareness on energy and climate issues: an Energy-Bike generating power through pedalling, a CO2-Game visualising emissions in real time, and a Walk-Power kinetic floor. These devices foster social participation (C12) and educational value, in line with NEB principles, while requiring careful assessment of maintainability (C8) and integration in the heritage context (C2);

- Module 3 (M3)—Smart Heritage Building for Energy/IEQ optimisation: M3 focuses on improving IEQ and building system integration. Measures include optimised HVAC and lighting controls (UNI EN 15232 [53]), replacement of deteriorated floors to integrate underfloor fan coils, and reversible finishing treatments to preserve the historical layer stratifications while ensuring decorum. This module directly addresses energy performance (C3–C4), conservation risks and durability (C7), and visitor comfort (C6).

- Horizontal internal partition. The analyses indicate the need to restore the acoustic and functional performance of the exhibition rooms by replacing the deformed wooden floors with a new interlocking plank system laid on site on a stabilised substrate. The new floor is detached by a few centimetres from the perimeter walls, preserving the perceptual distinction between the historic envelope and the new intervention. A continuous peripheral band accommodates the distribution networks of the building services systems, including the integration of underfloor fan-coil units. This band is finished with an accessible wooden grille to facilitate routine and extraordinary maintenance operations.

- Artificial lighting control system. In accordance with UNI EN 15232 [53], the introduction of occupancy sensors allows the automatic switching of lighting systems based on a calibrated occupancy factor (Foc), achieving a theoretical 10–15% reduction in electrical consumption for indoor lighting. The implementation of dimming controls enables dynamic adjustment of luminous flux within the exhibition halls, thereby enhancing visual comfort and ensuring optimal conditions for the perception of artworks.

- Interior finishes. The intervention aims to achieve a coherent interpretation of the surface stratigraphy, stabilising surviving plastered and decorated portions while discreetly concealing later additions and technical service ducts related to electrical or HVAC systems. Wooden inserts in the intrados of window and door frames re-establish the formal and material continuity of the lost cornices. At the junction between reconstructed vaults and the supporting masonry, a narrow separation joint highlights the volumetric independence of the vault, ensuring aesthetic legibility and compatibility with conservation principles.

4. Results and Discussion

- Energy retrofitting in heritage buildings cannot be evaluated solely in technical terms; cultural, perceptual, and governance dimensions must be integrated.

- Modularity offers a flexible way to combine efficiency, participation, and cultural activation, enabling tailored solutions that can be scaled or adapted.

- Decision-support methods such as AHP provide transparency and robustness, ensuring that trade-offs are explicit and that stakeholder perspectives can be incorporated into prioritisation.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| BMS | Building Management System |

| CAPEX | Capital Expenditure |

| COP | Coefficient Of Performance |

| CR | Consistency Ratio |

| EER | Energy Efficiency Ratio |

| EU | European Union |

| GWP | Global Warming Potential |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| MCDA | Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis |

| MiBACT | Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism |

| MTTR | Mean Time to Repair |

| NEB | New European Bauhaus |

| OPEX | Operational Expenditure |

| ONU | United Nations Organization |

| PSC | Perovskite Solar Cell |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| RES | Renewable Energy Sources |

| UGR | Unified Glare Rating |

| UNI | Italian Organization for Standardization |

| VRF | Variable Refrigerant Flow |

References

- European Commission. Circular Economy Action Plan; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament; Council of the European Union. Energy Efficiency Directive; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2015; Volume A/RES/70/1. [Google Scholar]

- Buda, A.; Pracchi, V.; Sannasardo, R. Built Cultural Heritage and Energy Efficiency. The Sicily Case: Pros and Cons of an Innovative Experience. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 296, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciribini, G. Il Sistema Normativo. Recuperare 1984, 13, 396–398. [Google Scholar]

- Sterman, J. Business Dynamics, System Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World; Shelstad, J.J., Ed.; Irwin McGraw-Hill: London, UK, 2000; ISBN 0-07-231135-5. [Google Scholar]

- UNI 8290-1:1981; Residential Building. Building Elements. Classification and Terminology. Ente Nazionale Italiano di Normazione: Milano, Italy, 1981.

- UNI 11277:2008; Building Sustainability. Ecocompatibility Requirements and Needs of New and Renovated Residential and Office Building Design. Ente Nazionale Italiano di Normazione: Milano, Italy, 2008.

- UNI EN 16798-1:2019; Energy Performance of Buildings—Ventilation for Buildings. Ente Nazionale Italiano di Normazione: Milano, Italy, 2019.

- ISO 15686-4:2014; Building Construction—Service Life Planning—Part 4: Service Life Planning Using Building Information Modelling. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- UNI EN 15643:2021; Sustainability of Buildings—A Framework for the Assessment of Buildings and Civil Engineering Works. Ente Nazionale Italiano di Normazione: Milano, Italy, 2021.

- ISO 21929-1:2011; Sustainability in Building Construction—Sustainability Indicators. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- European Parliament. Delivering the European Green Deal; Ufficio Delle Pubblicazioni dell’Unione Europea: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO; World Heritage Centre. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, D. Economics and Culture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, E.; Polo López, C.S.; Franco, G. A Conceptual Framework on the Integration of Solar Energy Systems in Heritage Sites and Buildings. In Proceedings of the Florence Heritec 2020, Florence, Italy, 14–16 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2018/844 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 Amending Directive 2010/31/EU on the Energy Performance of Buildings and Directive 2012/27/EU on Energy Efficiency; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Communities. D.L. 192/2005; Implementation of Directive (EU) 2018/844 Amending Directive 2010/31/EU on the Energy Performance of Buildings and Directive 2012/27/EU on Energy Efficiency, Directive 2010/31/EU on the Energy Performance of Buildings, and Directive 2002/91/EC on the Energy Performance of Buildings; Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana (GURI): Rome, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Battisti, A. Guidelines for Energy Efficiency in the Cultural Heritage. TECHNE J. Technol. Archit. Environ. 2016, 12, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ministero della Cultura. Linee di Indirizzo per Il Miglioramento Dell’efficienza Energetica Nel Patrimonio Culturale; Ministero della Cultura: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pracchi, V.; Buda, A. Le Linee Di Indirizzo per Il Miglioramento Dell’efficienza Energetica Nel Patrimonio Culturale: Indagine per la Definizione di Uno Strumento Guida Adeguato Alle Esigenze Della Tutela. In Restauro: Conoscenza, Progetto, Cantiere, Gestione; Ercolino, M.G., Ed.; Quasar Edizioni: Roma, Italy, 2020; Volume Sezione 5.2, pp. 772–782. [Google Scholar]

- Lucchi, E.; Pracchi, V. Efficienza Energetica e Patrimonio Costruito: La Sfida del Miglioramento Delle Prestazioni Nell’edilizia Storica; Maggioli Editore: Santarcangelo di Romagna, Italy, 2013; Volume 662, ISBN 8838762600. [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza, L.F.; de Gracia, A.; Pisello, A.L. Integration of Renewable Technologies in Historical and Heritage Buildings: A Review. Energy Build. 2018, 177, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, G.; Verde, L.; Olofsson, T. A Review on Technical Challenges and Possibilities on Energy Efficient Retrofit Measures in Heritage Buildings. Energies 2022, 15, 7472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, A.; Lucchi, E.; Maturi, L. Building Integrated Photovoltaic in Heritage Contexts Award: An Overview of Best Practices in Italy and Switzerland. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 863, 012018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Medici, S. Italian Architectural Heritage and Photovoltaic Systems. Matching Style with Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNI EN 16883:2017; Conservation of Cultural Heritage—Guidelines for Improving the Energy Performance of Historic Buildings. Ente Nazionale Italiano di Normazione: Milano, Italy, 2017.

- Fusco Girard, L.; Baycan, T.; Nijkamp, P. Sustainable City and Creativity: Promoting Creative Urban Initiatives; Ashgate Publishing: Aldershot, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Della Torre, S. Italian Perspective on the Planned Preventive Conservation of Architectural Heritage. Front. Archit. Res. 2021, 10, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISTAT. BES 2019: Equitable And Sustainable Well-Being in Italy; Italian National Institute of Statistics: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Crova, C. Le Linee Guida Di Indirizzo per Il Miglioramento Dell’efficienza Energetica Nel Patrimonio Culturale. Architettura, Centri e Nuclei Storici Ed Urbani: Un Aggiornamento Della Scienza Del Restauro. In Proceedings of the Le Nuove Frontiere del Restauro. Trasferimenti, Contaminazioni, Ibridazioni, Atti del XXXIII Convegno Internazionale Scienza e Beni Culturali, Bressanone, Italy, 27–30 June 2017; pp. 179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonara, G. Energy Efficiency as a Protection Tool. Energy Build. 2015, 95, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greffe, X. Is Heritage an Asset or a Liability? J. Cult. Herit. 2004, 5, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plevoets, B.; Van Cleempoel, K. Adaptive Reuse of the Built Heritage: Concepts and Cases of an Emerging Discipline; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth, G.J. Senses of Place: Senses of Time; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco Girard, L. Creativity, Resilience: Toward New Development Strategies of Port Areas through Evaluation Processes. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 13, 161–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list?module=treaty-detail&treatynum=199 (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- UNESCO; World Heritage Centre. Intergovernmental Committee for the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Vecco, M. Genius Loci: The Evaluation of Places between Instrumental and Intrinsic Values. BDC Bollettino Del. Centro Calza Bini 2019, 19, 473–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, K. Architecture Reborn: Converting Old Buildings for New Uses; Rizzoli: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Vandesande, A.; Verstrynge, E.; Van Balen, K. Preventive Conservation—From Climate and Damage Monitoring to a Systemic and Integrated Approach. In Proceedings of the International WTA, Leuven, Belgium, 3–5 April 2019; CRC Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Della Torre, S. A Coevolutionary Approach as the Theoretical Foundation of Planned Conservation of Built Cultural Heritage. In Preventive Conservation—From Climate and Damage Monitoring to a Systemic and Integrated Approach, Proceedings of the International WTA-PRECOM3OS Symposium, Leuven, Belgium, 3–5 April 2019; CRC Press: London, UK, 2020; pp. 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D. The Value of Cultural Heritage: What Can Economics Tell Us? Capturing the Public Value of Heritage—London; English Heritage: Swindon, UK, 2006; pp. 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Broström, T.; Svahnström, K. Solar Energy and Cultural-Heritage Values. In Proceedings of the World Renewable Energy Conference; Low-Energy Architecture, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, 13–15 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Site. In Proceedings of the IInd International Congress of Architects and Technicians of Historic Monuments, Venice, Italy, 25–34 May 1964; ICOMOS: Venice, Italy, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). SHC TASK 59. EBC ANNEX 76. Historic Buildings: Deep Renovation of Historic Buildings towards Lowest Possible Energy Demand and CO2 Emission (NZEB); International Energy Agency (IEA): Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. New European Bauhaus Investment Guidelines; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ciampa, F.; Fabbricatti, K.; Freda, G.; Pinto, M.R. A Playground and Arts for a Community in Transition: A Circular Model for Built Heritage Regeneration in the Sanità District. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbricatti, K.; Pinto, M.R. Il Ruolo Dell’arte Nella Rigenerazione Dell’ambiente Costruito. Le Residenze d’artista per i Contesti Fragili. In Playgrounds e Arte per Comunità in Transizione. Patto di Cura per le Città; La scuola di Pitagora: Napoli, Italy, 2023; pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Masimba, F.; Appiah, M.; Zuva, T. A Review of Cultural Influence on Technology Acceptance. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Multidisciplinary Information Technology and Engineering Conference (IMITEC), Vanderbijlpark, South Africa, 21–22 November 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco Girard, L. Una Nuova Economia Urbana Sostenibile e Solidale. Bene Comune 2016, 2, 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO; ICCROM; ICOMOS. The Nara Document on Authenticity; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- UNI EN 15232-1:2017; Energy Performance of Buildings—Energy Performance of Buildings—Part 1: Impact of Building Automation, Controls and Building Management—Modules M10-4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10. Ente Nazionale Italiano di Normazione: Milano, Italy, 2017.

- Benjamin, W. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction; Arendt, H., Ed.; Illuminations; Belknap Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaka, A.; Nemery, P. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis: Methods and Software, 1st ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2013; ISBN 9781118644928. [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti, V.; Bottero, M.; Mondini, G. Decision Making and Cultural Heritage: An Application of the Multi-Attribute Value Theory for the Reuse of Historical Buildings. J. Cult. Herit. 2014, 15, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Montis, A.; De Toro, P.; Droste-Franke, B.; Omann, I.; Stagl, S. Assessing the Quality of Different MCDA Methods. In Alternatives for Environmental Valuation; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; pp. 99–133. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L. Decision Making with the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Int. J. Serv. Sci. 2008, 1, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. The Analytic Hierarchy Process; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Belvedere, A.; Montana, S. Palazzo Belmonte a Palermo. Lex. Storie E Archit. Sicil. 2013, 16, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Capitano, V. Giuseppe Venanzio Marvuglia Architetto Ingegnere Docente; Mazzone: Palermo, Italy, 1984; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Cultural and Environmental Heritage of Palermo. Palazzo Belmonte—Riso; Archive of Department of Cultural and Environmental Heritage: Palerm, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso, C. Palermo in Camicia Nera. Le Trasformazioni Dell’identità Urbana (1922–1943). In Mediterranea Ricerche Storiche; Mediterranea Associazione: Bologna, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Scaturro, G. Danni Di Guerra e Restauro Dei Monumenti, Palermo 1943–1945. Ph.D. Thesis, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, Napoli, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Regione Sicilia. CIS Palermo Centro Storico; Regione Sicilia: Sicily, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| NEB Values | Main Topic | Sub-Topics of Analysis | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability Aesthetics | T1. Cultural values and authenticity | Authenticity and integrity | [11,12,28,29,37,52] |

| Reversibility | |||

| Distinguishability | |||

| Conservation of historical layer stratifications | |||

| Sustainability | T2. Energy and environmental performance | Demand reduction | [9,18,32,33,34,50] |

| “Efficiency first” principle | |||

| Share of energy demand covered by RES | |||

| Avoided emissions | |||

| Compliance with UNI EN 16798 | |||

| Aesthetics | T3. Technological integration | Typological and material compatibility | [5,6,14,19,27] |

| Visual impacts | |||

| Morphological adaptation | |||

| Mimetic technologies | |||

| Compatibility with traditional materials | |||

| Sustainability | T4. Comfort and usability | IEQ (temperature, humidity, CO2, illuminance, noise) | [9,23,24,27,53] |

| Use-specific requirements | |||

| Accessibility and usability | |||

| Aesthetics | T5. Landscape and perception | Landscape impact | [3,14,15,35,45] |

| Consistency with context and skyline | |||

| Public perception | |||

| Minimization of visual alterations | |||

| Inclusion | T6. Governance, participation and cultural activation | Co-design | [15,30,31,46,54] |

| Stakeholder engagement | |||

| Social acceptability | |||

| Creative/training/educational activities consistent with NEB values |

| System Type | Model | Nominal Cooling Power (kW) | Nominal Heating Power (kW) | EER | COP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat Pump | WSAN-XIN 30.2 (Clivet S.p.A.) | 82.2 | 93.0 | 2.85 | 3.21 |

| VRF | M5-XMi 450T (Clivet S.p.A.) | 45 | 45 | 3.3 | 3.85 |

| Generation System Type | Fan-Coil Model | Nominal Heating Capacity (kW) | Nominal Cooling Capacity (kW) | N° Fan-Coil Floor 0 | N° Fan-Coil Floor 1 | N° Fan-Coil Floor 2 | Total Number of Fan Coils | Total Heating Power (kW) | Total Cooling Power (kW) | Total Energy Consumption (kWh) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat Pump | CFCC 5 CC2 R3 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 9 | 4 | 8 | 21 | 79.8 | 73.5 | |

| CFCC 7 CC2 R3 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 37.6 | 34.4 | ||

| 117.4 | 107.9 | 89,059.52 | ||||||||

| VRF | DNB-2-XMiD45 | 5 | 4.5 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 20 | 18 | |

| DNB-2-XMiD36 | 4 | 3.6 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 16 | 14.4 | ||

| DNB-2-XMiD28 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 12.8 | 11.2 | ||

| 48.8 | 43.6 | 30,992.69 | ||||||||

| 120,052.21 |

| Fan-Coil Model | Nominal Electrical Absorption (kW) | N° Fan-Coil Floor 0 | N° Fan-Coil Floor 1 | N° Fan-Coil Floor 2 | Total Number of Fan Coils | Total Electrical Power (kW) | Total Energy Consumption (kWh) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFCC 5 CC2 R3 | 0.024 | 9 | 4 | 8 | 21 | 0.504 | |

| CFCC 7 CC2 R3 | 0.047 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 0.376 | |

| 0.88 | 1837.22 | ||||||

| DNB-2-XMi D45 | 0.035 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0.14 | |

| DNB-2-XMi D36 | 0.025 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0.1 | |

| DNB-2-XMi D28 | 0.025 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0.1 | |

| 0.34 | 709.84 | ||||||

| 2547.06 |

| Lamp Model | Electrical Absorption (kW) | N° Lamp Floor 0 | N° Lamp Floor 1 | N° Lamp Floor 2 | Total Number of Lamps | Total Electrical Power (kW) | Total Energy Consumption (kWh) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QP26 | 0.0219 | 0 | 49 | 37 | 86 | 1.88 | |

| R938 | 0.047 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 16 | 0.76 | |

| 2.64 | 7893.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Medici, S.; Cataldi, G.; Costanzo, V.; Vitale, M.R. Balancing Cultural Values and Energy Transition: A Multi-Criteria Approach Inspired by the New European Bauhaus. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11255. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411255

De Medici S, Cataldi G, Costanzo V, Vitale MR. Balancing Cultural Values and Energy Transition: A Multi-Criteria Approach Inspired by the New European Bauhaus. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11255. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411255

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Medici, Stefania, Giuseppe Cataldi, Vincenzo Costanzo, and Maria Rosaria Vitale. 2025. "Balancing Cultural Values and Energy Transition: A Multi-Criteria Approach Inspired by the New European Bauhaus" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11255. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411255

APA StyleDe Medici, S., Cataldi, G., Costanzo, V., & Vitale, M. R. (2025). Balancing Cultural Values and Energy Transition: A Multi-Criteria Approach Inspired by the New European Bauhaus. Sustainability, 17(24), 11255. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411255