1. Introduction

The continuous consumption of world resources without proper planning has led to the planet facing severe consequences at an accelerating rate, including global warming, resource depletion, and environmental degradation [

1]. Nowadays, on emergent grounds, world leaders are making concerted efforts to slow down the consumption of natural resources [

2]. Recently, researchers have highlighted the role of the construction sector in this crisis; in [

3], it was mentioned that the building sector is responsible for 39% of all CO

2 emissions, and more than a third of the usage of total energy and CO

2 emissions is a result of the building sector in the developed and developing nations [

4]. This makes it a primary target for mitigation strategies. The pressure from developed countries worldwide to reduce carbon emissions is also growing. Reference [

5] pointed out that new rules, such as updated EU guidelines, now require a transition to a building stock with no emissions by 2050. This makes it very important for countries to use strong assessment techniques. Scientists believe that ecological damage has reached, or is nearing, a point of no return. Given the growing demand and rising oil prices, world-leading economies are seriously considering shifting to renewable energy sources to reduce production costs and simultaneously slow greenhouse gas emissions, thereby controlling global warming [

6]. Saudi Arabia, for example, has set ambitious targets to cut greenhouse gas emissions, including the 2060 Zero-Carbon target [

7]. The building sector is a primary contributor to greenhouse gas emissions and can also be viewed as an enabler of a more sustainable built environment [

8].

According to [

9], Green Building is a concept that focuses on minimizing a building’s environmental impact throughout its lifecycle. In contrast, in [

10] green buildings were considered as tools that improve environmental efficiency and health while minimizing adverse effects on human health. According to [

11], it is a practice aimed at creating a structure that is environmentally and resource-efficient throughout its entire life cycle. These features can all be identified using a rating system. Ref. [

12] stated that a building rating system is a framework used to assess the environmental performance and sustainability of buildings. According to [

13], building rating systems are tools that classify buildings based on environmental sustainability, building efficiency, and user health.

In addition to their environmental benefits, green buildings also provide health and economic advantages. Research has shown that certified buildings with a rating system can enhance patient treatment and sleep quality [

14]. Maintaining a high standard of indoor environmental quality is essential for promoting health and well-being. This is particularly significant because people who work in offices, stores, and healthcare settings spend a lot of time indoors—up to 90% of their time, as highlighted by [

15]. Furthermore, workplaces with green elements and adequate ventilation can improve cognitive function by 101% and increase employee productivity by up to 8% [

16]. For example, the transition to a green workplace at the CH2 building in Melbourne has led to a notable 10.9% increase in staff productivity [

17]. Implementing a green rating system has also been shown to yield direct financial benefits. The Construction Marketplace Smart-Market Report reveals that commercial green buildings have achieved 8–9% reductions in operating costs, a 7.5% increase in building value, and a 6.6% increase in return on investment. As indicated by the Greening of Corporate America Smart Market Report, commercial green buildings experience a 3.5% increase in occupancy and a 3% increase in rent [

18].

The purpose of implementing green building rating systems worldwide is to promote sustainable practices in buildings, as they significantly impact the global environment. Implementing green building ideas still requires significant adjustments at many points in the process, including design, construction, and daily operations. Due to these changes, new materials, methods, and approaches are necessary that differ from the old ones. People accustomed to traditional methods often resist adopting new, more environmentally friendly approaches. The hesitation among stakeholders to adopt this practice stems from concerns about its risks, the initial cost of adaptation, and unfamiliarity with the practice itself. Overcoming these barriers is essential to successfully implementing environmentally friendly building principles [

19].

Saudi Arabia faces multiple obstacles that make it challenging for the country to fully utilize and implement these technologies [

20]. A primary factor is the limited awareness and understanding of green building concepts and their advantages. Another barrier is the scarcity of experts and professionals in green building within the kingdom [

21]. These experts are crucial since they help to guide and inform the use of green construction principles. In addition, the high initial expenditures of adding green building features and technologies are also a substantial barrier in Saudi Arabia.

Regionally, there is also resistance to change and a lack of readiness to make sustainability a top priority in the building business. Additionally, obtaining the necessary government permissions and clearances to use green building methods is challenging [

22]. According to a 2014 report by the U.S. Green Building Council, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) had 866 LEED projects as of 2014, with only 106 certified. LEED is an internationally acknowledged green building certification program developed by the U.S Green Building Council [

23]. The UAE had the most registered projects (650), followed by Qatar (88 registered, 13 certified) and Saudi Arabia (83 registered, 4 certified). There were fewer developments in Oman, Bahrain, and Kuwait. In 2014, only 4 of the 106 approved buildings were from Saudi Arabia, despite the country being a major player in the construction industry. However, the adoption of green buildings has been rising in the GCC. By 2023, Saudi Arabia had 1816 registered projects, of which 1162 were certified. The UAE had 2275 registered projects, but only 569 were certified [

9]. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are important players in LEED projects that support the Sustainable Development Goals. The UAE is ahead in renewable energy regulations, whereas Saudi Arabia is working on its Vision 2030 [

24]. In 2023, the U.S. Green Building Council ranked Saudi Arabia sixth, reflecting its dedication and goals towards sustainability [

25].

The primary objective of this research is to identify and evaluate critical barriers to the adoption of Green Building Rating Systems (GBRS) in Saudi Arabia’s construction industry and systematically prioritize strategic interventions to overcome them. Ultimately, comprehending these obstacles and assessing the efficacy of proposed solutions will further promote the adoption of GBRS and bolster sustainability initiatives both within Saudi Arabia and on a global scale. The utilization of GBRS can assist projects in improving their environmental performance, elevating efficiency, and decreasing lifecycle costs. To achieve these objectives, the study seeks to answer two questions:

What are the different kinds of barriers that act as a blockade while adopting GBRS in Saudi Arabia?

How do Saudi construction industry stakeholders prioritize specific strategies to overcome these barriers in terms of importance and effectiveness?

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides a global literature review and identifies key barriers to the adoption of the green building rating system.

Section 3 provided the techniques and methodologies adopted in this research, including the survey design and the Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) framework.

Section 4 presents the results of the data analysis.

Section 5 discusses the findings of this research and compares them with the previous studies and the specific Saudi environment. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the study by summarizing the main contributions and offering policy recommendations.

3. Methodology

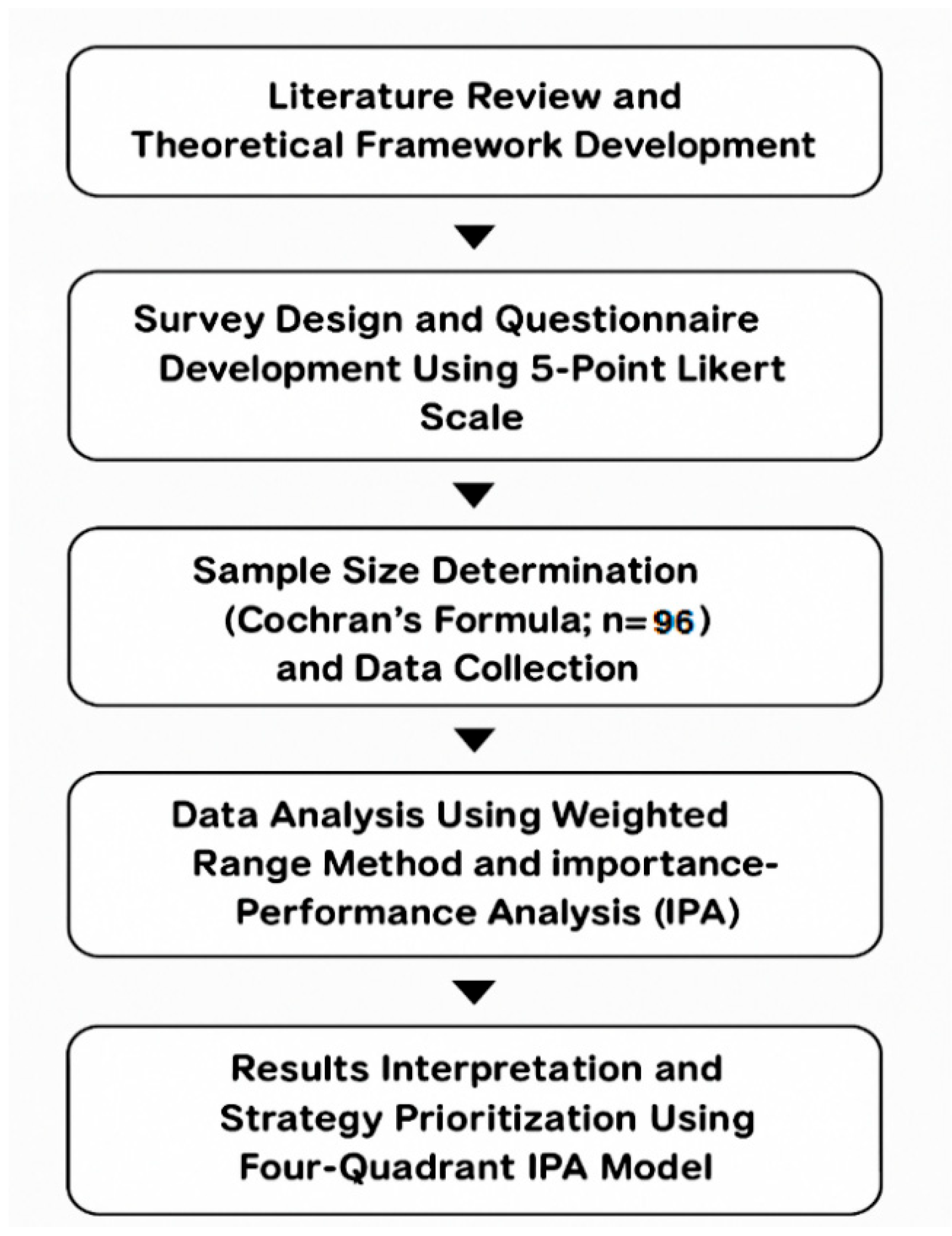

This section outlines the research design, data collection, sample size determination (calculated using Cochran’s formula), and the application of Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) as the primary analytical tool.

3.1. Research Design

The research began by reviewing previous studies to identify barriers to implementing green building rating systems across various construction industries and to explore potential solutions to overcome them. To identify these barriers, the author used major academic databases, including Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus. Merging these databases provided bibliographic information that boosted academic publication. The search strategy utilized specific keywords such as “green buildings,” “green rating systems,” “implementation barriers,” and “Saudi Arabia construction industry.” The efforts were then narrowed down to reviewing the related literature specifically in Saudi Arabia’s construction industry. This literature review was crucial, as it helped to identify 10 key barriers and 8 potential solutions. Later, these barriers were categorized using a thematic analysis methodology.

Afterward, these barriers and solutions were analyzed using multiple analytical tools and techniques. Once this analysis was completed, a survey questionnaire was prepared, targeting practitioners across various groups, including industry professionals, government organizations, and commercial sectors, as the unit of analysis. The survey was distributed via the snowball technique to ensure it reached a broader audience across the public and private sectors of Saudi construction. To ensure data integrity, the survey was designed in accordance with ethical research standards, and data were kept private; it was promised that they would be destroyed after the research was conducted. This encouraged the respondent to provide honest feedback, especially for organizational and policy barriers, without any fear. The quantitative survey approach is selected for this study, as it aligns with the methodologies of [

19,

30], which successfully employed this approach in their respective studies, recognized as studies on green building barriers in Ghana and Malaysia.

The survey was used to evaluate the criticality of the identified barriers and to assess the importance and effectiveness of the proposed strategies. An analysis of the survey data was then conducted, and the results were discussed to develop conclusive arguments.

Figure 1 illustrates the research methodology flowchart.

3.2. Data Collection

Through an extensive review of current practices and consultation with experts in the field, this research aims to identify the most significant barriers and propose critical strategies to address them. Surveys with construction experts, including executives and field engineers with 7–20 years of experience, identified barriers and solutions. The research aims to survey various public and private organizations. The questionnaire targets multiple segments, each with specific questions to elicit participants’ views. Research objectives involve designing questions to explore barriers to implementing the green building rating system and proposing solutions. Data collected via surveys from the target audience is compiled and evaluated to inform the conclusion.

As the targeted audience comes from diverse backgrounds and occupations, they are expected to have varying perceptions of both obstacles and strategies; thus, most of the questionnaire used a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree,” for each proposed statement. The Likert scale is one of the most widely used instruments in research, developed by Rensis Likert [

47]. To analyze responses more effectively, each Likert scale point was assigned a numerical value.

Table 1 shows the categories, scale values, and weighted ranges used in the analysis.

3.3. Population and Sampling Techniques

Since the size of the target population was unknown, this study estimated the minimum sample size using Cochran’s formula from ‘Sampling Techniques’ [

48], as shown below:

Z = Z value (1.96 used for 95% confidence level);

P = Percentage picking a choice, expressed as a decimal (0.5 used for sample size needed);

C = confidence interval, expressed as a decimal (0.1 used for ±10% margin of error)

Therefore, a sample size of 96 has been selected. Survey distribution was conducted directly with a carefully selected audience to obtain the most accurate and valuable input.

3.4. Data Analysis Tool

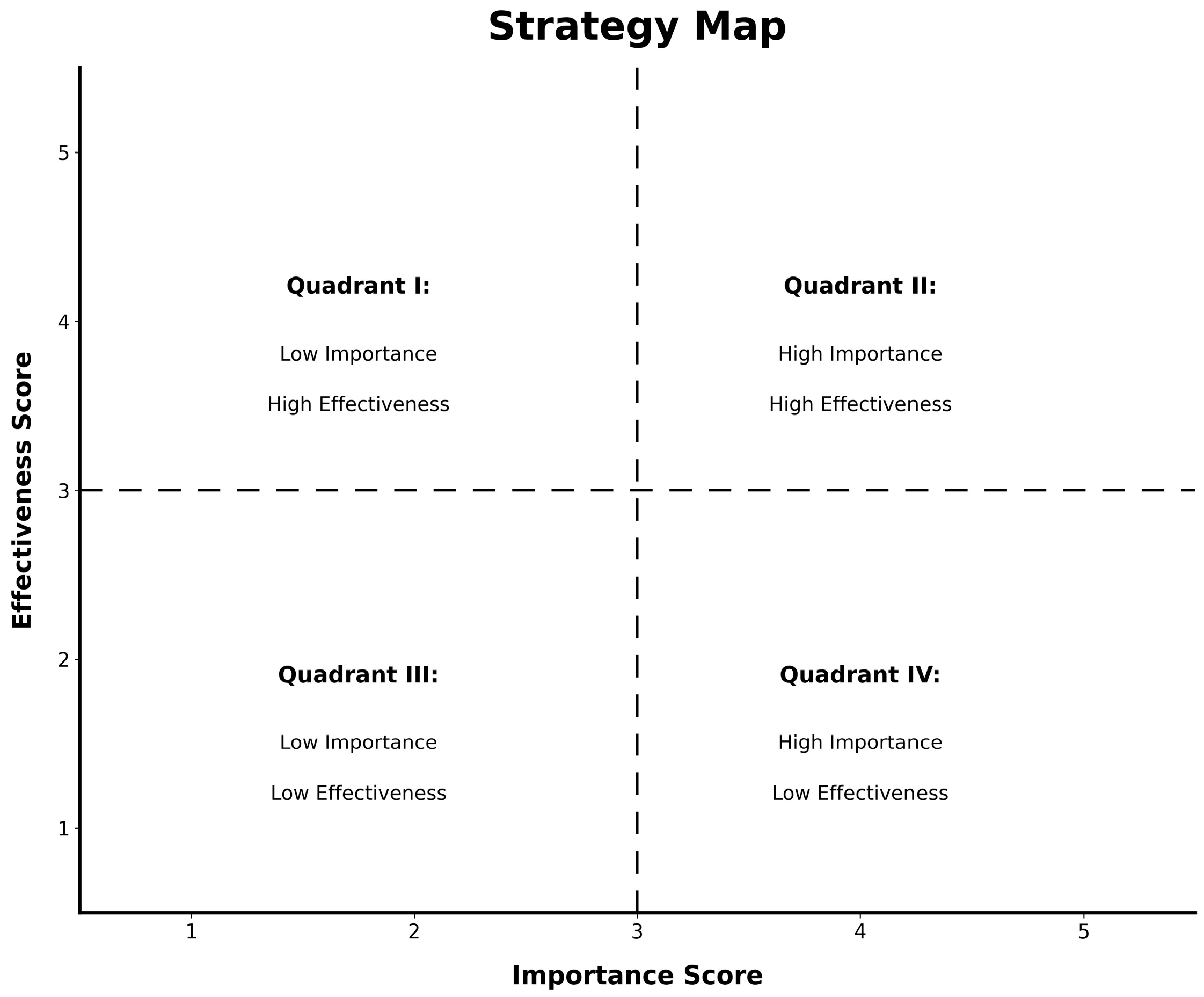

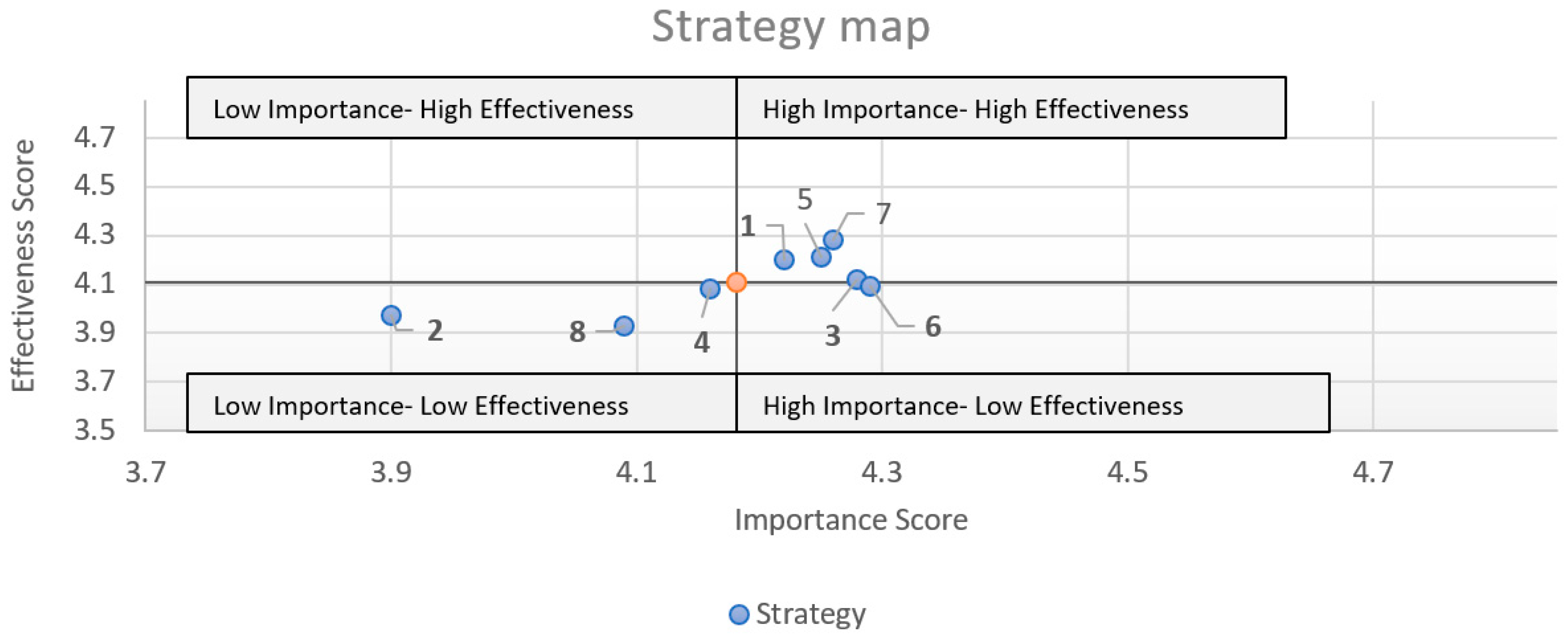

In the field of research work, there are numerous methods for ranking data, such as the Relative Importance Index (RII); however, this study decides to adopt the Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) model, as IPA not only does data ranking but also visualizes the relationship between the importance of strategy and its effectiveness. The proposed strategies are prioritized using the IPA model, which assesses their importance-effectiveness ratio to highlight the high-priority strategies decision-makers should focus on. The model was derived from the importance-performance analysis (IPA), developed by Martilla and James, which identifies the product or service attributes an organization should focus on to enhance customer satisfaction [

49].

The model is divided into four quadrants based on their importance and effectiveness levels. The axis is determined by importance and effectiveness values, which divide the graph into four quadrants: high importance-high effectiveness, low importance-high effectiveness, high importance-low effectiveness, and low importance-low effectiveness. To determine the threshold values for all importance and effectiveness, this study uses the mean, the overall average score, as it better differentiates between high- and low-performing strategies in the collected data. Importance measures how necessary it is to have this strategy in place, and effectiveness assesses the extent to which it will solve the issue.

Figure 2 shows how these strategies are sorted.

5. Discussion

This research aims to investigate the barriers to the adoption of green building rating systems and to propose strategic solutions to overcome them. This research has found that a lack of awareness across the public and private sectors is one of the most critical barriers. This finding is parallel to the study by [

29], which was conducted in Ghana, where low public demand was identified as a primary obstacle. However, it contradicts studies conducted in developed countries such as the United States and the UK, where awareness levels are high. Technical implementation and regulatory complexity act as barriers to implementing GBRS in the studies by [

19]. For the Saudi Context, A possible explanation for the lack of awareness barrier is that stakeholders are not fully aware of the long-term financial and environmental advantages, leading to low demand for implementing these systems in their projects. To address this issue, 45% of the respondents in this research emphasized the importance of launching public awareness campaigns on green building in collaboration with leading construction firms and the government. These programs would open new doors for economic expansion and foster beneficial cooperation between the public and private sectors. A clear distinction emerged regarding the nature of these barriers. The findings of this research highlight that economic barriers, specifically initial high costs, are a common challenge shared worldwide. Similarly, they have been identified by research consistent with findings in the US, the UK [

19], and Ghana [

29]. However, one finding specific to the Saudi context is the high ranking of ‘Government Funding’ as a critical solution (Quadrant I). In developed markets where private financing models often drive adoption, this study shows that the Saudi market differs because it relies on centralized government intervention, likely due to the top-down approach of the Vision 2030 program.

Technical barriers include a lack of professional personnel, information, and reliable sources related to green building rating systems, which is another major obstacle. It is crucial to start green building achievement awards and recognition initiatives. Establishing rewards and incentive programs that emphasize the creation of creative projects and the promotion of new entrants is crucial. Government-sponsored programs could help reduce the numerous obstacles new players face, enabling them to introduce their goods and services.

It is crucial to prequalify green building experts to receive the rating system classification. Remarkably, 46% of those surveyed think it is very important. By offering their professional insights to the public seeking assistance with green building solutions, consultants, advisors, and certifying organizations play a vital role. The government might start offering certification courses and training programs that would educate prospective applicants on cutting-edge concepts and emerging trends.

According to the participants’ responses, most are in favor of establishing standards, procedures, operations, and protocols for sustainable construction. Of those surveyed, 47% think it is very important, 37% think it is quite important, and 14% think it is somewhat important.

A lack of funding and financing solutions for green building projects is another challenge identified in this study. To counter this, 51% of respondents believe it is very important to introduce financial incentives, such as tax exemptions, to encourage owners to adopt green building principles. In comparison, 28% say it is quite important, and 17% feel it is somewhat important. Just 17% believe it to be somewhat important. In general, 79% of respondents support offering monetary rewards to encourage property owners to adopt green building practices.

Establishing minimal sustainable construction standards (calling for a minimum rating level) for all new government projects. It is noteworthy that 39% of those surveyed think it is very essential. Establishing fundamental standards for green buildings is essential because it empowers all parties involved to act at any scale.

Study Implications

The implications of this research are important for all construction industry stakeholders who prefer to adopt green building rating systems (GBRS) in their respective projects in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. In terms of real-world effects, the research’s outcomes provide stakeholders with a roadmap for adopting the green rating system. The study highlights that while implementing the high-importance strategies of this research, stakeholders can put themselves in a position where they can obtain economic benefits established in the broader literature, such as saving operational expenses by 8–9%, increasing the overall value of the building by 7.5%, and improving return on investment by 6.6%. GBRS adoption benefits human capital in more ways than just financial ones. It also makes interior spaces healthier, increasing employee productivity by up to 8% [

18]. These benefits make it a powerful strategy to improve business performance and support the national goals of Saudi Vision 2030, as it enhances the sustainability and productivity of the physical environment.

Theoretical implications: this study identifies several areas for researchers to address, thereby overcoming the topic’s research limitations in future studies. These areas include understanding the adaptation framework of GBRS in a rapidly developing economy, performing a thorough performance-based evaluation of the existing standard to analyze how it affects the real world, and performing an in-depth analysis to measure the number of job creations, as it is one of the growing concerns, and to understand how culture is affecting the adaptation of GBRS. Additionally, more strategies and different analysis methods could be used to compare and recommend the best result.

This study offers a definitive, actionable framework for decision-makers in government, business, and project ownership concerning managerial implications. The study’s findings suggest that the government and policymakers should make it easier for green projects to be funded, offer tax exemptions and other financial incentives to encourage the adoption of green buildings, and mandate that all new government projects meet minimum sustainable building standards. The top priority for industry leaders and professionals is to close the knowledge gap. The study suggests achieving this by launching public awareness campaigns to highlight the long-term benefits of green buildings, making prequalification programs mandatory for specialized consultants, and introducing green education subjects at universities to develop professional experts in this field. Another finding of this study suggests that project owners and stakeholders should shift their focus from initial costs to long-term value. They can achieve this by employing a lifecycle cost analysis, leveraging available financial incentives, and engaging a qualified green building consultant early in the design process to mitigate risks and optimize outcomes.

6. Conclusions

As significant energy users, buildings have contributed to the development of global sustainable building standards. Saudi Vision 2030 encompasses initiatives to improve sustainability in energy, housing, and water sectors, with green building standards promoting more environmentally friendly practices. This study used the Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) model to evaluate the identified barriers to the adoption of Green Building Rating Systems (GBRS) in Saudi Arabia and to prioritize eight strategic solutions. These strategies offered a targeted roadmap for policymakers aligned with Vision 2030. A survey of stakeholders revealed key barriers, including a lack of awareness and experience with green buildings, which highlights the need for awareness campaigns and training. Infrastructure challenges are critical, suggesting the creation of a government or private sector committee to investigate root causes and develop solutions. Collaboration across sectors is vital to the successful adoption of green building systems.

The survey results in this research show a significant increase in the use of green building ratings in Saudi Arabia compared to 2014. Despite this positive trend, many areas require improvement and have untapped potential for future growth. It is worth noting that the survey participants had varying levels of familiarity with green building rating systems, with the majority expressing a lack of awareness. In addition, it was surprising to discover that the majority of construction practitioners had not been involved in any prior green building projects, highlighting a significant lack of practical experience in the sector. These findings offer opportunities for targeted initiatives that aim to increase awareness and develop practical expertise, further advancing sustainable construction in the region.

To more effectively advance green building initiatives in Saudi Arabia and overcome current study limitations, future research should take a wider perspective. This includes evaluating current green building standards to understand their impact on design and construction, engaging a broad range of stakeholders to identify problems and solutions, and examining economic effects such as job creation, financial benefits, and cost savings from green practices. Moreover, addressing overlooked cultural and regulatory barriers with targeted strategies is crucial, supported by high-level government and private-sector commissions that research and consult on these obstacles. Given the rapid evolution of the Saudi construction sector, it is recommended that this IPA evaluation be conducted annually to establish updated standards and track the shifting priorities of industry stakeholders. This collaborative, research-based strategy will help inform decisions, develop policies, and promote sustainable practices nationwide and globally.

Every study has limitations; this study has some as well. Firstly, the data relies solely on stakeholders’ perceptions, whereas market sentiment may differ from objective performance data. Secondly, while the sample size of 96 in this study is statistically sufficient, as calculated using Cochran’s formula, a larger sample in future studies would allow for a more granular segmentation analysis, such as comparing government vs. private-sector views. Due to the sampling limitation, the study did not study the relation between occupational background and scoring outcome, which can be addressed in future work. Lastly, the study is context-specific to Saudi Arabia, so its results should be cautiously generalized to other GCC nations.