Sustainable Urban Healthcare Accessibility: Voronoi Screening and Travel-Time Coverage in Bangkok

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Global Context

1.2. Bangkok and Thailand Context

1.3. Point-Pattern and Density Diagnostics for Healthcare Facilities

1.4. Voronoi Structures for Healthcare Screening

1.5. Areal Interpolation and Population Allocation

1.6. Burden Screening Indicators and Underserved Thresholding

1.7. Network and Isochrone Accessibility

1.8. Aims and Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Spatial Units

2.1.1. NHSO Healthcare Facility Points

2.1.2. Administrative Boundaries and Population Statistics

2.1.3. Urban Land Use and Planning Zones

2.2. Data Pre-Processing

2.3. Methodological Framework

2.3.1. Average Nearest Neighbor by Service Tier

2.3.2. Kernel Density Estimation by Service Tier

2.3.3. Voronoi Geometric Partitions Construction

2.3.4. Population Weighted Allocation to Voronoi Polygons

2.3.5. Zoning Overlay and Facility Siting Alignment

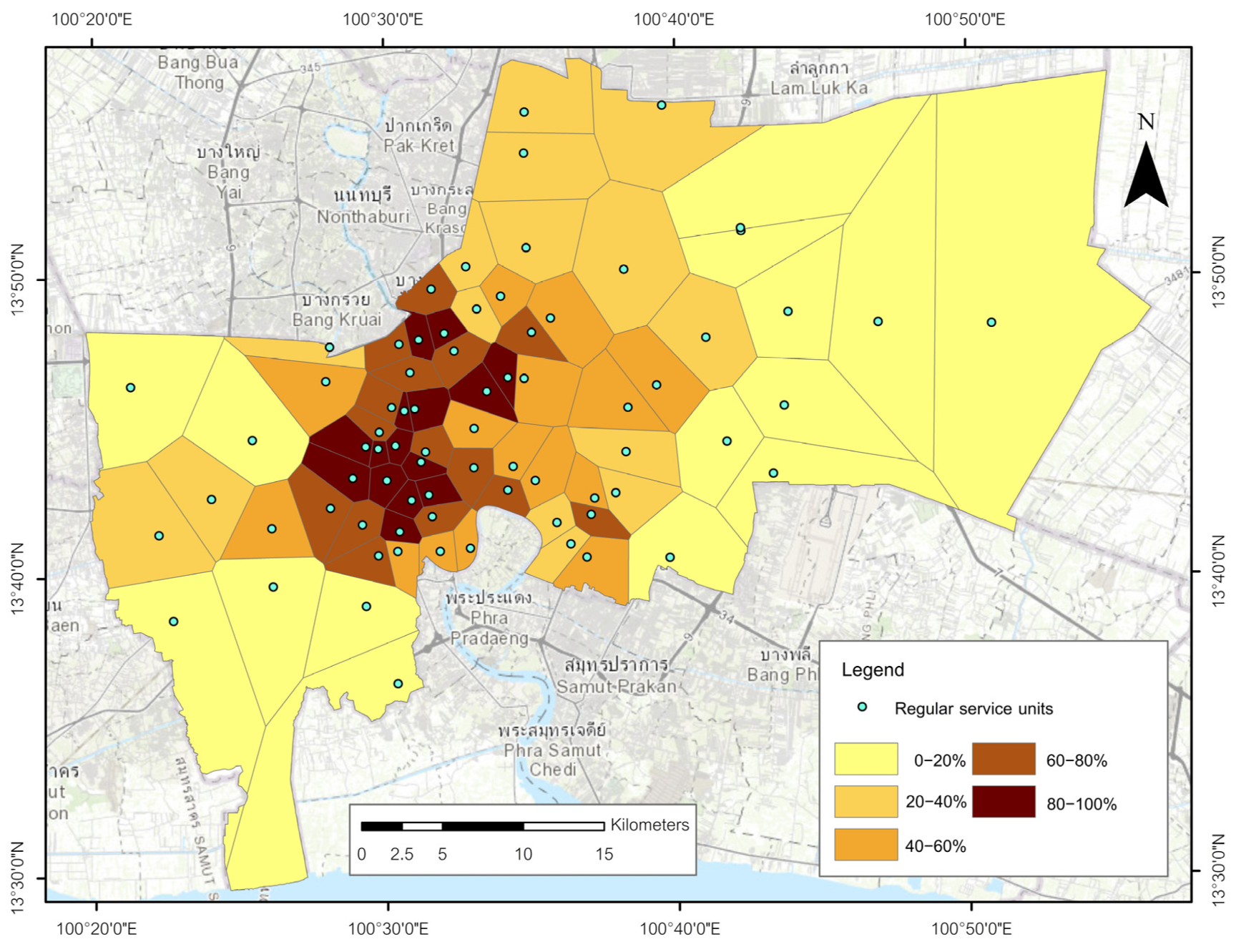

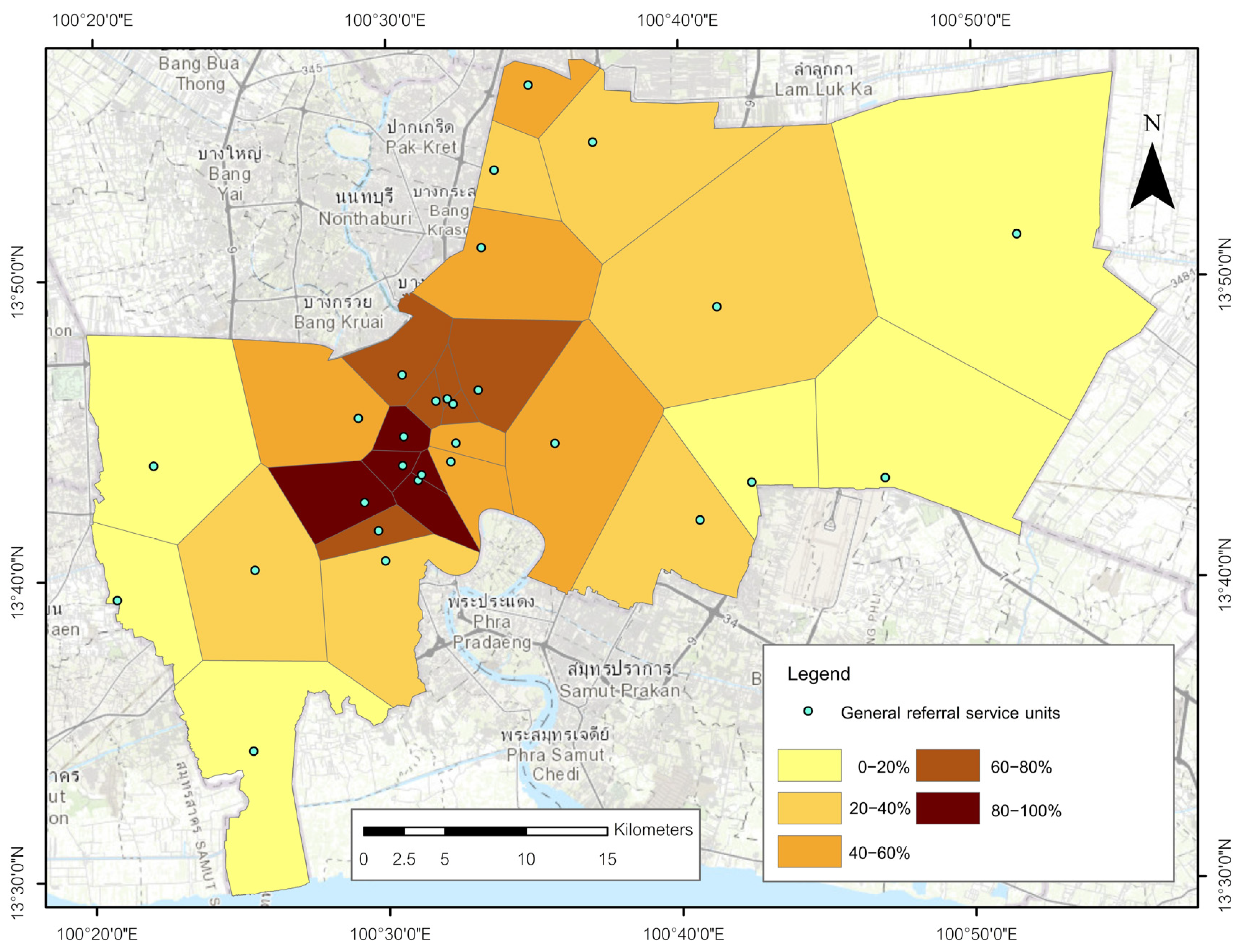

2.3.6. Burden Screening Maps Based on Voronoi Partitions

2.3.7. Network Based Isochrone Accessibility

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Distribution and Population Context

3.2. Facility Pattern and Density Diagnostics

3.3. Voronoi Geometric Partitions

3.4. Population Assigned to Voronoi Partitions

3.5. Travel-Time Accessibility Based on Isochrone Analysis

3.6. Zoning Alignment

3.7. Service-Area Footprints Versus Planning Intent

3.8. Burden Screening Based on Voronoi Partitions

4. Discussion

4.1. Synthesis of Spatial Structure, Partitions, and Travel-Time Access

4.2. Interpreting Facility Pattern Diagnostics

4.3. Voronoi Geometric Partitions as a Transparent Nearest-Facility Framework

4.4. Population Assignment and Its Interpretive Boundaries

4.5. Burden Indicator BDSP: Definition, Interpretation, and Policy Utility

4.6. Travel-Time Accessibility and Cumulative Isochrone Interpretation

4.7. Zoning Alignment and Service-Footprint Context

4.8. Integrated Identification of Spatial Gaps Across Service Tiers

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANN | Average nearest neighbor |

| BDSP | Beneficiary Density per Service Partition |

| BMA | Bangkok Metropolitan Administration |

| EPSG | European Petroleum Survey Group code |

| GIS | Geographic information system |

| KDE | Kernel density estimation |

| NHSO | National Health Security Office (Thailand) |

| ORS | OpenRouteService |

| OSM | OpenStreetMap |

| QGIS | Quantum GIS |

| UTM | Universal Transverse Mercator |

Appendix A

| Component | Parameter | Value Used |

|---|---|---|

| A. Software, data, and spatial domain | ||

| ArcGIS Pro | Version | 3.4.0 |

| QGIS | Version | 3.22 (ORS Tools) |

| CRS | Projected | UTM Zone 47N (EPSG:32647) |

| Study extent | Analysis mask | Bangkok administrative boundary |

| Facilities (year 2024) | Counts by tier | Primary 294; Regular 75; Referral 29 (NHSO register) |

| B. Pattern diagnostics and partitions | ||

| ANN (per tier) | Distance metric; inference | Euclidean; familywise interpretation of p-values (no recomputation) |

| KDE (per tier) | Kernel; bandwidth; cell size | Quadratic; automatic (per tier); 3.545 m |

| Voronoi | Tool; clipping; topology | Create Thiessen Polygons; clipped to BMA boundary; closure/no overlaps; one polygon per facility |

| Population allocation | Rule; QC; limitation | Area-weighted within subdistrict; conservation and non-negative checks; screening-only for non-residential tracts |

| C. Zoning overlay and interpretation | ||

| Point overlay | Counts per zone by tier | Spatial Join |

| Area overlay | Partition shares by zone | Intersect > Dissolve > Summary Statistics; areas via Calculate Geometry Attributes |

| Interpretation | Planning context | Read against statutory planning intent only (not present-day operational alignment) |

| D. Burden indicator and mapping | ||

| Indicator | Definition; units | see Section 2.3.6; reported per km2 |

| Classification | Percentiles (per tier) | 0–20, 20–40, 40–60, 60–80, 80–100; within-tier only |

| E. Network isochrones for Primary tier (on QGIS 3.22/ORS plugin) | ||

| Engine & mode | ORS Tools (server-side) | driving-car; time impedance |

| Ranges (minutes) | Cumulative bands | 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60 |

| Location type | Origin semantics | start (away from facility) |

| Dissolve | During ORS request | OFF (retain per-facility features) |

| Smoothing factor | Polygon generalization | Not set (default) |

| Output & reprojection | Formats; CRS | GeoJSON/Shapefile; reproject to EPSG:32647 |

| City-wide rings | Workflow | Fix geometries > Dissolve by minute > Split by minute > Difference (60−50, …, 10−5; 5 direct) > Merge |

| Edge clean-up | Trim | Buffer 100 m on each ring |

| Speeds & caveat | Model basis | Server-side model speeds; no temporal variability (screening coverage) |

| F. Network isochrones for Regular & Referral tiers (on ArcGIS Pro 3.4.0) | ||

| Engine & network | Service Area | Integrated BMA/OTP network; time impedance; cumulative 5–60 min breaks |

| Direction | Flow | Away From Facility |

| U-turns | Setting | Allowed |

| Restrictions | Travel rules | Oneway = Prohibited; Turn = Prohibited |

| Invalid locations | Handling | Ignore Invalid Locations = Enabled |

| Polygon type | Generalization | Generalized |

| Edge clean-up | Trim | 100 m |

| Multiple facilities | Overlap; type | Overlapping; Rings (do not include area of smaller breaks) |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO); UN-Habitat. Global Report on Urban Health: Equitable, Healthier Cities for Sustainable Development; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-92-4-156527-1. [Google Scholar]

- Gligorić, K.; Kamath, C.; Weiss, D.J.; Bavadekar, S.; Liu, Y.; Shekel, T.; Schulman, K.; Gabrilovich, E. Revealed versus Potential Spatial Accessibility of Healthcare and Changing Patterns during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Comm. Med. 2023, 3, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, A.; Sreeganga, S.D.; Ramaprasad, A. Access to Healthcare during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Vernez Moudon, A.; Lowe, M.; Cerin, E.; Boeing, G.; Frumkin, H.; Salvo, D.; Foster, S.; Kleeman, A.; Bekessy, S.; et al. What Next? Expanding Our View of City Planning and Global Health, and Implementing and Monitoring Evidence-Informed Policy. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e919–e926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favarão Leão, A.L.; Gierbolini-Rivera, R.D.; Franco Silva, M.; Shaw, C.; O’Connor, Á.; Salvo, D.; Reis, R.S. Spatial Indicators of Inequity in Urban Health Research: A Scoping Review. Discov. Public Health 2025, 22, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phoglad, S. Understanding Accessibility to Medical and Healthcare Services for Informal Workers in Bangkok During the COVID-19 Outbreak. J. Popul. Soc. Stud. (JPSS) 2021, 30, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peungnumsai, A.; Miyazaki, H.; Witayangkurn, A.; Kim, S.M. A Grid-Based Spatial Analysis for Detecting Supply-Demand Gaps of Public Transports: A Case Study of the Bangkok Metropolitan Region. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iamtrakul, P.; Chayphong, S.; Kantavat, P.; Hayashi, Y. Identification of Key Determinants on Quality-of-Life Related Transportation: A Spatial Statistical Modeling Approach Based on Transport Accessibility and Subjective Well-Being. Eng. Sci. 2024, 30, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pueboobpaphan, R.; Pueboobpaphan, S.; Sukhotra, S. Acceptable Walking Distance to Transit Stations in Bangkok, Thailand: Application of a Stated Preference Technique. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 99, 103296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreemongkol, K.; Lohatepanont, M.; Cheewinsiriwat, P.; Bunlikitkul, T.O.; Supasaovapak, J. GIS Mapping Evaluation of Stroke Service Areas in Bangkok Using Emergency Medical Services. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gu, H.; Shi, Y. Spatial Accessibility Analysis of Medical Facilities Based on Public Transportation Networks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, J.; Angeles, G. Kernel Density Estimation as a Technique for Assessing Availability of Health Services in Nicaragua. Health Serv. Outcomes Res. Method 2007, 7, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, T.; Chen, J.; Li, A.; Wang, J.; Shen, D. Evaluating Spatial Accessibility to General Hospitals with Navigation and Social Media Location Data: A Case Study in Nanjing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mello-Sampayo, F. Spatial Interaction Model for Healthcare Accessibility: What Scale Has to Do with It. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, F.A.V.S.; Varnier-Almeida, R.M.; Nobre, F.F. Defining Catchment Areas for Public Hospitals in the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro through Weighted Voronoi Diagrams. Cad. Saúde Pública 2000, 16, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naabi, S.; Al Nasiri, N.; Al-Awadhi, T.; Abdullah, M.; Abulibdeh, A. An Equity-Based Spatial Analytics Framework for Evaluating Pharmacy Accessibility Using Geographical Information Systems. Healthc. Anal. 2025, 7, 100401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, A. A Smart Spatial Routing and Accessibility Analysis System for EMS Using Catchment Areas of Voronoi Spatial Model and Time-Based Dijkstra’s Routing Algorithm. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonprong, S.; Punturasan, N.; Varnakovida, P.; Prechathamwong, W. Towards Sustainable Urban Mobility: Voronoi-Based Spatial Analysis of EV Charging Stations in Bangkok. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duczmal, L.H.; Moreira, G.J.P.; Burgarelli, D.; Takahashi, R.H.C.; Magalhães, F.C.O.; Bodevan, E.C. Voronoi Distance-Based Prospective Space-Time Scans for Point Data Sets: A Dengue Fever Cluster Analysis in a Southeast Brazilian Town. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2011, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comber, A.; Zeng, W. Spatial Interpolation Using Areal Features: A Review of Methods and Opportunities Using New Forms of Data with Coded Illustrations. Geogr. Compass 2019, 13, e12465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Martinez, A. Areal Interpolation Using Parcel and Census Data in Highly Developed Urban Environments. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Wang, R.; Liu, L.; Wu, H. Fine-Scale Dasymetric Population Mapping with Mobile Phone and Building Use Data Based on Grid Voronoi Method. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Li, M.; Wu, S. Spatial Analysis and Evaluation of Medical Resource Allocation in China Based on Geographic Big Data. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortwein, A.; Redecker, A.P.; Moos, N. Health-Related Disparities in the Metropolitan Region Ruhr: Large-Scale Spatial Model of Local Asthma Prevalence, Accessibility of Health Facilities, and Socioeconomic and Environmental Factors. PFG 2022, 90, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, H.; Namimi-Halevi, C.; Luxenburg, O.; Grinbaum Arizon, A.; Tagar, Z.; Bromberg, M.; Eisenberg, V.H. Optimizing Nation-Wide Locations of Dialysis Centers: A Geographic Information System-Based Approach to Improve Healthcare Accessibility and Availability. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2025, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, C.M.; Encalada-Abarca, L.; Rocha, J.; Vale, D.S. Identifying Pharmacy Gaps: A Spatiotemporal Study of Multimodal Accessibility throughout the Day. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2025, 24, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Lee, J.; Gim, T.-H.T. 15-Minute City for All? Rethinking the 15-Minute City for Urban Older Populations. Appl. Geogr. 2025, 184, 103747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kwan, M.-P.; Liu, D.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y. 15-Minute City beyond the Urban Core: Lessons from the Urban-Suburban Disparity in PCR Accessibility within the X-Minute Framework. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2025, 198, 104546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fernández, O.; Michel, G.R. Spatial Accessibility to Healthcare Facilities: GIS-Based Public-Private Comparative Analysis Using Floating Catchment Methods. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Cheng, Y. Modelling the Spatial Accessibility of the Elderly to Healthcare Services in Beijing, China. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2019, 46, 1132–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s) | Study Area | Methodologies Applied | Key Findings & Relevance to Screening |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rezende et al. (2000) [15] | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | Weighted Voronoi Diagrams | Demonstrated that Voronoi polygons can be weighted by hospital capacity (admissions) to define operational catchments, refining the standard geometric approach. |

| Spencer & Angeles (2007) [12] | Nicaragua | Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) | Established KDE as a method for converting discrete supply/demand points into continuous surfaces to visualize access ratios. |

| Tao & Cheng (2019) [30] | Beijing, China | 2-Step Floating Catchment Area (2SFCA) | Integrated travel time with supply-demand ratios for elderly healthcare, highlighting the importance of group-specific access screening. |

| Peng et al. (2020) [22] | China (Mobile Data) | Grid Voronoi & Dasymetric Mapping | Used a grid-based Voronoi method to stabilize population distribution from mobile phone data, addressing spatial heterogeneity. |

| Qian et al. (2020) [13] | Nanjing, China | KDE & Grid-based Accessibility | Applied grids to stabilize demand signals, supporting the use of reproducible geometric units for screening diagnostics. |

| Liu et al. (2022) [11] | Chongqing, China | ANN, KDE, Accessibility Models | Used Average Nearest Neighbor (ANN) and clustering diagnostics to link facility arrangements with core-periphery accessibility differences. |

| Alamri (2023) [17] | (General Framework) | Voronoi & Network Routing | Combined Voronoi catchments with Dijkstra’s algorithm, validating the compatibility of Voronoi geometry with network-based travel time modeling. |

| Boonprong et al. (2024) [18] | Bangkok, Thailand | Voronoi Spatial Analysis | Applied Voronoi partitions to diagnose EV charging station distribution in Bangkok, confirming the method’s utility for local infrastructure screening. |

| Al-Naabi et al. (2025) [16] | Muscat, Oman | Voronoi & Buffer Analysis | Combined Voronoi polygons with distance thresholds to flag underserved pharmacy locations, serving as a direct template for geometric screening. |

| Pérez-Fernández & Michel (2025) [29] | Panama | Floating Catchment & Spatial Statistics | Used Getis-Ord Gi* and floating catchments to identify hot/cold spots of access, reinforcing the need for reproducible statistical indicators. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boonprong, S.; Punturasan, N.; Kamsing, P.; Torteeka, P.; Cao, C.; Piolueang, N.; Satapanajaru, T.; Xu, M. Sustainable Urban Healthcare Accessibility: Voronoi Screening and Travel-Time Coverage in Bangkok. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11241. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411241

Boonprong S, Punturasan N, Kamsing P, Torteeka P, Cao C, Piolueang N, Satapanajaru T, Xu M. Sustainable Urban Healthcare Accessibility: Voronoi Screening and Travel-Time Coverage in Bangkok. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11241. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411241

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoonprong, Sornkitja, Nathapat Punturasan, Patcharin Kamsing, Peerapong Torteeka, Chunxiang Cao, Ngamlamai Piolueang, Tunlawit Satapanajaru, and Min Xu. 2025. "Sustainable Urban Healthcare Accessibility: Voronoi Screening and Travel-Time Coverage in Bangkok" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11241. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411241

APA StyleBoonprong, S., Punturasan, N., Kamsing, P., Torteeka, P., Cao, C., Piolueang, N., Satapanajaru, T., & Xu, M. (2025). Sustainable Urban Healthcare Accessibility: Voronoi Screening and Travel-Time Coverage in Bangkok. Sustainability, 17(24), 11241. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411241