How Digital Technology Shapes the Spatial Evolution of Global Value Chains in Financial Services

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Design

2.1. Theoretical Analyses

2.2. Model Construction

2.2.1. Dynamic Spatial Durbin Model

2.2.2. Geographical and Temporal Weighted Regression (GTWR)

2.2.3. Spatial Mediating Effect Model

2.3. Variables and Data

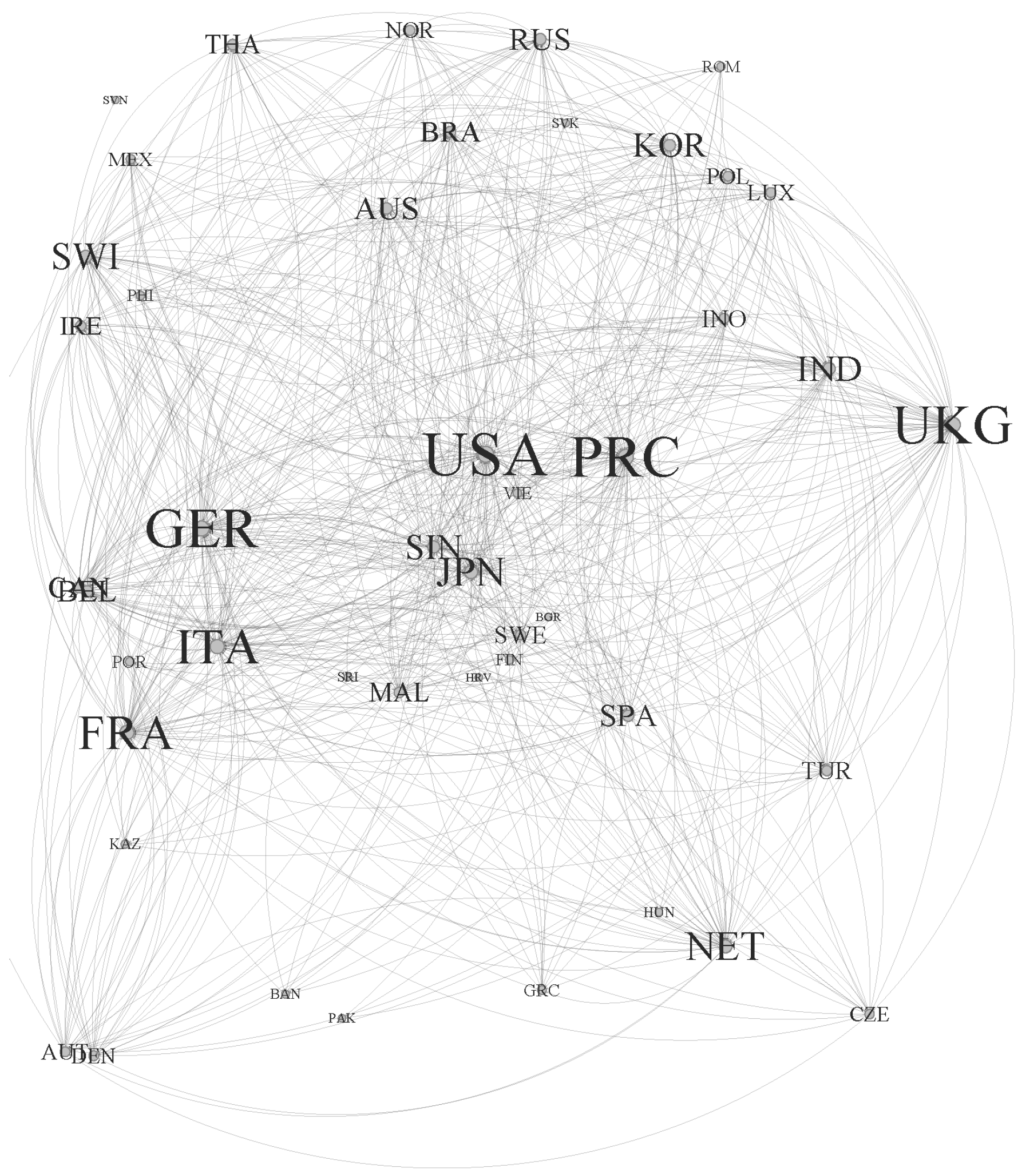

2.3.1. Network Metrics of Financial Services Global Value Chains

2.3.2. Digital Technology Index (TIMG2023)

2.3.3. Control Variables

2.3.4. Setting of Spatial Weight Matrix

3. Empirical Analyses

3.1. Analysis of the Dynamic Spatial Durbin Model Results

3.2. Analysis of the Results of the Geographical and Temporal Weighted Regression Model

3.3. Endogeneity Tests

3.4. Robustness Tests

3.5. Heterogeneity Tests

4. Mechanisms Testing

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Spatial Correlation Test and Model Selection

| Year | logdeg | logdt | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Z | p-Value | I | Z | p-Value | |

| 2013 | 0.225 | 3.680 | 0.000 | 0.306 | 4.974 | 0.000 |

| 2014 | 0.221 | 3.620 | 0.000 | 0.327 | 5.252 | 0.000 |

| 2015 | 0.229 | 3.727 | 0.000 | 0.327 | 5.249 | 0.000 |

| 2016 | 0.226 | 3.679 | 0.000 | 0.309 | 4.942 | 0.000 |

| 2017 | 0.207 | 3.401 | 0.001 | 0.309 | 4.959 | 0.000 |

| 2018 | 0.207 | 3.409 | 0.001 | 0.306 | 4.917 | 0.000 |

| 2019 | 0.211 | 3.472 | 0.001 | 0.306 | 4.913 | 0.000 |

| 2020 | 0.212 | 3.485 | 0.001 | 0.312 | 4.995 | 0.000 |

| 2021 | 0.196 | 3.246 | 0.001 | 0.301 | 4.836 | 0.000 |

| Statistical Quantities | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| LMError(Burrideg) test | 38.071 | 0.000 |

| LMError(Robust) test | 35.291 | 0.000 |

| LMLag(Anselin) test | 57.475 | 0.000 |

| LMLag(Robust) test | 54.695 | 0.000 |

| LR(SLM) test | 30.54 | 0.0001 |

| LR(SEM) test | 29.56 | 0.0001 |

| Wald(SLM) test | 31.05 | 0.0001 |

| Wald(SEM) test | 29.50 | 0.0001 |

| Hausman test | 16.36 | 0.0220 |

References

- Gereffi, G.; Humphrey, J.; Sturgeon, T. The governance of global value chains. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 2005, 12, 78–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.; Fleury, A.; Fleury, M.T. Digital power: Value chain upgrading in an age of digitization. Int. Bus. Rev. 2021, 30, 101850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambos, B.; Brandl, K.; Perri, A.; Scalera, V.G.; Van Assche, A. The nature of innovation in global value chains. J. World Bus. 2021, 56, 101221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilyard, J.; Zhao, S.; You, J.J. Digital innovation and Industry 4.0 for global value chain resilience: Lessons learned and ways forward. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2021, 63, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tang, T.; Ah, R.; Luo, L. Has digital technology promoted the restructuring of global value chains? Evidence from China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 81, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Bian, R.; Anwar, S. Can digital transformation of services promote participation in manufacturing global value chains? Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 81, 1074–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Kim, H.H.; Lee, H.; Lee, J. Regional production networks, service offshoring, and productivity in East Asia. Jpn. World Econ. 2010, 22, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Z.; Mao, Y.; Zeng, C.; Wang, Z. To What Extent and How Does Internet Penetration Affect a Firm’s Upgrading in the Global Value Chain? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dranove, D.; Garthwaite, C. Artificial Intelligence, the Evolution of the Healthcare Value Chain, and the Future of the Physician; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nano, E.; Stolzenburg, V. The Role of Global Services Value Chains for Services-Led Development. In Global Value Chain Development Report 2021: Beyond Production; Xing, Y., Gentile, E., Dollar, D., Eds.; Asian Development Bank, Research Institute for Global Value Chains at the University of International Business and Economics, the World Trade Organization, the Institute of Developing Economies–Japan External Trade Organization, and the China Development Research Foundation: Beijing, China, 2021; pp. 105–133. [Google Scholar]

- Konishi, Y. Global value chain in services. J. Southeast Asian Econ. 2019, 36, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jiang, X.; Shi, M.; Yang, Y. Impact of artificial intelligence on manufacturing industry global value chain position. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, R.; Zucchella, A. Industry 4.0, global value chains and international business. Multinatl. Bus. Rev. 2017, 25, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, G.; Li, M. Research on the Impact of the Input Level of Digital Economics in Chinese Manufacturing on the Embedded Position of the GVC. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, R.; Nadvi, K. Global value chains and the rise of the Global South: Unpacking twenty-first century polycentric trade. Glob. Netw. 2018, 18, 207–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antràs, P. De-Globalisation? Global Value Chains in the Post-COVID-19 Age; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kano, L.; Tsang, E.W.K.; Yeung, H.W. Global value chains: A review of the multi-disciplinary literature. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2020, 51, 577–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevik, S. Promise (un) kept? Fintech and financial inclusion. Scott. J. Political Econ. 2025, 72, e70012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevik, S. Prometheus Unbound: What Makes Fintech Grow? Econ. Politics 2025, 37, 1145–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevik, S. Is Schumpeter right? Fintech and economic growth. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2025, 34, 1095–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Ming, T.H.; Baigh, T.A.; Sarker, M. Adoption of artificial intelligence in banking services: An empirical analysis. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2023, 18, 4270–4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desyatnyuk, O.; Naumenko, M.; Lytovchenko, I.; Beketov, O. Impact of digitalization on international financial security in conditions of sustainable development. Probl. Ekorozwoju 2024, 19, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramod, D. Robotic process automation for industry: Adoption status, benefits, challenges and research agenda. Benchmarking Int. J. 2022, 29, 1562–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Lu, B. Application of edge computing and IoT technology in supply chain finance. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 108, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liang, X.; Wen, Q.; Wan, E. The analysis of financial network transaction risk control based on blockchain and edge computing technology. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 5669–5690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savchuk, N.; Bludova, T.; Leonov, D.; Murashko, O.; Shelud’Ko, N. Innovation imperatives of global financial innovation and development of their matrix models. Invest. Manag. Financ. Innov. 2021, 18, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.S.; Ma, C.Q.; Wang, Y. A new financial regulatory framework for digital finance: Inspired by CBDC. Glob. Finance J. 2024, 62, 101025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Pollard, J. The geography of money and finance. In Handbook on the Geographies of Money and Finance; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Coe, N.M.; Yeung, H.W.C. Global production networks: Mapping recent conceptual developments. J. Econ. Geogr. 2019, 19, 775–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereffi, G. What does the COVID-19 pandemic teach us about global value chains? The case of medical supplies. J. Int. Bus. Policy 2020, 3, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Du, D.; Li, Q. Characteristics and influencing factors of provincial high-end manufacturing innovation clusters in China: A big data analysis of technology-based enterprises. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2025, 18, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Qiu, Y. Impact of financial agglomeration on regional economic growth in China: A spatial correlation perspective. Sage Open 2023, 13, 21582440231196347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beugelsdijk, S.; Mudambi, R. MNEs as border-crossing multi-location enterprises: The role of discontinuities in geographic space. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2013, 44, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudambi, R.; Li, L.; Ma, X.; Makino, S.; Qian, G.; Boschma, R. Zoom in, zoom out: Geographic scale and multinational activity. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2018, 49, 929–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antràs, P.; De Gortari, A. On the geography of global value chains. Econometrica 2020, 88, 1553–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, T.; Supriyadi, A.; Cirella, G.T. Spatial pattern characteristics of the financial service industry: Evidence from Nanjing, China. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2022, 15, 595–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Mao, W.; Lin, X. Does the Adoption of Industrial Internet Platforms Expand or Reduce Geographical Distance to Customers? Evidence from China’s New Energy Vehicle Industry. Systems 2025, 13, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriset, B.; Malecki, E.J. Organization versus space: The paradoxical geographies of the digital economy. Geogr. Compass 2009, 3, 256–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Cheng, S.; Liu, Y. Green digital finance and technology diffusion. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Cao, C.; He, Z.; Feng, C. Examining the coupling coordination relationship between digital inclusive finance and technological innovation from a spatial spillover perspective: Evidence from China. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade 2023, 59, 1219–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, Y.; He, B. Spatial spillover effects of digital finance on corporate ESG performance. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xue, X.; Ding, W.; Feng, M. The promotion effect and spillover effect of financial technology on regional innovation: Evidence from China. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2024, 37, 1767–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Hui, S.K.; Bell, D.R. Spatiotemporal analysis of imitation behavior across new buyers at an online grocery retailer. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 47, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Hu, S.; Zeng, G. Spatio-Temporal Evolution of Green Technology Innovation Networks and its Proximity Mechanism in the Context of Digital Transformation: The Case of Yangtze River Delta in China. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2025, 18, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J. Digital Technology and Value Chain Agglomeration: Evidence from East Asia. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade 2023, 59, 2866–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qinghua, Z.; Songwen, L.; Xiaomei, H.; Jing, S. Spatial-temporal pattern and impact factor of digital technology entrepreneurship in China. Geo-Graph. Sci. 2025, 45, 988–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmer, M.P.; Erumban, A.A.; Los, B.; Stehrer, R.; de Vries, G.J. Slicing up global value chains. J. Econ. Perspect. 2014, 28, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Guo, J.; Chen, X. Automation and value-chain embedment: Evidence from Chinese manufacturing firms. Appl. Econ. 2025, 57, 3608–3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capello, R.; Dellisanti, R.; Perucca, G. At the territorial roots of global processes: Heterogeneous modes of regional involvement in Global Value Chains. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2024, 56, 833–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.E.; Li, J.; Brouthers, K.D. International business in the digital age: Global strategies in a world of national institutions. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2023, 54, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.R.; Liu, Y.J.; Fu, H.; Jin, Y.; Zhou, G. Spatio-temporal differentiation pattern and influence mechanism of housing vacancy in shrinking cities of Northeast China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2024, 79, 1412–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhorst, J.P. Dynamic spatial panels: Models, methods, and inferences. J. Geogr. Syst. 2012, 14, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhorst, J.P. Matlab software for spatial panels. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2014, 37, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Wu, B.; Barry, M. Geographically and temporally weighted regression for modeling spatio-temporal variation in house prices. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2010, 24, 383–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.M.; Wang, G.M. Urbanization, industrial structure upgrading and high-quality economic development—Test of mediation effect based on spatial Durbin model. Syst. Eng. Theory Pract. 2023, 43, 648–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldwin, R.; Venables, A.J. Spiders and snakes: Offshoring and agglomeration in the global economy. J. Int. Econ. 2013, 90, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Jing, M.; Fei, C.; Xinyu, H. Research on Ecological Innovation Connection and Network Structure of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Urban Agglomeration. Urban Probl. 2020, 305, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.M.; Zhang, M. Measuring the Development of the Global Digital Economy: Stylized Facts Based on TIMG Index. Chin. Rev. Finance Stud. 2021, 13, 40–56+118–119. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Pan, Y.C.; Chen, Z.C. The Spatial Network Embeddedness of Digital Service Trade and the Promotion of China’s Service Industry Global Value Chain. Mod. Finance Econ. J. Tianjin Univ. Finance Econ. 2023, 43, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, W.; Wu, X.J.; Ye, P.L. The impact of digital service trade network on the domestic value added in exports–Evidence from cross-country data. J. Int. Trade 2022, 12, 90–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Q.I.U.; Huang, D. The structural characteristics of trade networks along the “belt and Road” and their impacts on technological progress—An study based on social network analysis. Econ. Theory Bus. Manag. 2021, 41, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.L.; Hong, C.L.; Sun, T.Y. Offshore services outsourcing network and upgrading in global value chain of service industry. J. World Econ. 2018, 41, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, O.; LeSage, J.P. Using the variance structure of the conditional autoregressive spatial specification to model knowledge spillovers. J. Appl. Econom. 2008, 23, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zheng, L.; Chen, Z.; Cheng, M.; Ren, Y. Digitalization through supply chains: Evidence from the customer concentration of Chinese listed companies. Econ. Model. 2024, 134, 106688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Kang, S.; Liu, W. Government open data and corporate supply chain concentration. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 102, 104144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lai, Q.; He, J. Does Digit. Technol. Enhanc. Glob. Value Chain Position? Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2024, 24, 856–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yang, S.; Yin, S.; Xu, H. Spatial-temporal dynamic characteristics and its driving mechanism of urban built-up area in Yangtze River Delta based on GTWR model. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2021, 30, 2594–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.; Sun, P. Spatial interaction between FDI and regional coordinated development in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2025, 34, 522–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, M.; Cotterlaz, P.; Mayer, T. The CEPII Gravity Database; CEPII: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Han, F.; Yang, L.G. How Does the Agglomeration of Producer Services Promote the Upgrading of Manufacturing Structure?: An Integrated Framework of Agglomeration Economies and Schumpeter’s Endogenous Growth Theory. J. Manag. World 2020, 36, 72–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| logdeg | 468 | 3.8528 | 0.7053 | 1.79 | 5.46 |

| logdt | 468 | 1.7418 | 0.1403 | 1.18 | 1.97 |

| peo | 468 | 0.6433 | 0.1485 | 0.24 | 0.89 |

| logm | 468 | 5.0738 | 0.6798 | 3.16 | 6.52 |

| urban | 468 | 1.0947 | 0.3016 | 0.29 | 1.61 |

| fd | 468 | 0.8571 | 0.3565 | 0.17 | 1.52 |

| logfdi | 468 | 5.2404 | 0.6951 | 3.52 | 7.12 |

| dof | 468 | 7.4507 | 0.7119 | 4.82 | 8.83 |

| Variable | Geographic Distance Matrix | Economic Distance Matrix | Nested Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|

| L.logdeg | 0.960 *** | 0.218 *** | 0.234 *** |

| (0.0496) | (0.0602) | (0.0602) | |

| logdt | −0.525 *** | −0.575 *** | −0.559 *** |

| (0.177) | (0.177) | (0.177) | |

| peo | 0.610 | −0.135 | −0.131 |

| (0.381) | (0.314) | (0.314) | |

| logm | 0.0582 | 0.213 ** | 0.206 * |

| (0.137) | (0.106) | (0.106) | |

| urban | −0.149 | −0.0668 | −0.0589 |

| (0.215) | (0.189) | (0.189) | |

| fd | 0.142 ** | 0.175 *** | 0.167 *** |

| (0.0631) | (0.0610) | (0.0610) | |

| logfdi | −0.0862 *** | 0.0675 ** | 0.0676 ** |

| (0.0326) | (0.0269) | (0.0269) | |

| dof | 0.115 *** | −0.0398 ** | −0.0378 * |

| (0.0229) | (0.0202) | (0.0202) | |

| N | 416 | 416 | 416 |

| R2 | 0.434 | 0.292 | 0.092 |

| Matrix Type | Variable | Short-Term | Long-Term | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Total Effect | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Total Effect | ||

| Geographic Distance Matrix | logdt | −0.673 (0.427) | 10.14 *** (2.875) | 9.467 *** (2.969) | −0.0868 (0.605) | 2.018 *** (0.593) | 1.931 *** (0.499) |

| control variables | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| Economic Distance Matrix | logdt | 0.878 (7.642) | 3.219 (7.625) | 4.098 *** (0.464) | −0.832 *** (0.251) | 4.383 *** (0.529) | 3.551 *** (0.404) |

| control variables | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| Nested Matrix | logdt | 1.357 (29.19) | 2.731 (29.17) | 4.088 *** (0.493) | −0.775 *** (0.248) | 4.255 *** (0.540) | 3.480 *** (0.422) |

| control variables | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| Bandwidth | Sigma | Residual Squares | AICc | R2 | R2 Adjusted | Spatio-Temporal Distance Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1127 | 0.1482 | 10.0775 | −306.463 | 0.9562 | 0.9555 | 0.2688 |

| Variable | Zero-Order | First-Order | Third-Order | Fourth-Order | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| logdeg | logdt | logdeg | logdt | logdeg | logdt | logdeg | logdt | |

| logdeg | 0.172 *** (0.007) | 0.178 *** (0.007) | 0.171 *** (0.007) | 0.172 *** (0.007) | ||||

| W * logdeg | 1.977 *** (0.312) | −0.710 *** (0.075) | 2.318 *** (0.258) | −0.848 *** (0.082) | 1.729 *** (0.226) | −0.757 *** (0.076) | 1.775 *** (0.218) | −0.733 *** (0.075) |

| logdt | 1.775 *** (0.675) | 2.459 *** (0.298) | 1.657 *** (0.246) | 1.883 *** (0.221) | ||||

| W * logdt | −4.778 *** (0.772) | 1.746 *** (0.183) | −5.600 *** (0.636) | 2.084 *** (0.201) | −4.119 *** (0.558) | 1.856 *** (0.187) | −4.238 *** (0.539) | 1.798 *** (0.184) |

| control variables | control | control | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| cons | −2.152 *** (0.501) | 0.855 *** (0.075) | −2.468 *** (0.255) | 0.878 *** (0.070) | −1.834 *** (0.228) | 0.866 *** (0.076) | −2.000 *** (0.214) | 0.874 *** (0.075) |

| N | 468 | 468 | 468 | 468 | 468 | 468 | 468 | 468 |

| R2 | 0.8652 | 0.6707 | 0.8597 | 0.6656 | 0.8865 | 0.6752 | 0.8815 | 0.6746 |

| Variables | SYSGMM | DIFFGMM |

|---|---|---|

| L.logdeg | 0.721 *** (15.48) | 0.287 *** (4.81) |

| logdt | −0.267 ** (−2.01) | −0.173 * (−1.83) |

| peo | −0.418 ** (−2.35) | −0.128 (−0.73) |

| logm | 0.099 *** (3.35) | 0.144 *** (2.82) |

| urban | 0.376 *** (3.92) | 0.286 * (1.76) |

| fd | 0.007 (0.11) | 0.014 (0.35) |

| logfdi | 0.023 (1.02) | 0.058 *** (3.44) |

| dof | 0.019 (1.07) | −0.025 * (−1.95) |

| sargan | 31.205 | 26.544 |

| sarganp | 0.182 | 0.543 |

| arm1 | −4.257 | −3.510 |

| arm2 | −0.397 | −0.526 |

| ar1p | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| ar2p | 0.691 | 0.599 |

| Unit Fixed Effects | Time Fixed Effects | Total Effect (2013–2018) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| logdt | 0.722 *** (0.198) | 0.256 * (0.140) | 0.658 * (0.368) |

| peo | 1.013 *** (0.345) | −0.251 (0.249) | 2.124 *** (0.731) |

| logm | 0.621 *** (0.0617) | 0.280 *** (0.0573) | 0.910 *** (0.0916) |

| urban | 1.235 *** (0.308) | 0.117 (0.224) | 0.667 (0.778) |

| fd | −0.113 (0.102) | 0.0130 (0.0699) | −0.0196 (0.258) |

| logfdi | 0.327 *** (0.0432) | 0.144 *** (0.0319) | 0.0157 (0.113) |

| dof | −0.138 *** (0.0243) | −0.0109 (0.0210) | −0.207 *** (0.0491) |

| Variable | Effect | High-Income Economies | Non–High-Income Economies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-term direct | 0.503 * (0.295) | −0.158 (0.273) | |

| Short-term indirect | 3.143 *** (0.888) | −0.0519 (0.479) | |

| logdt | Short-term total effect | 3.646 *** (1.066) | −0.210 (0.616) |

| Long-term direct | −0.682 (2.174) | −0.340 (0.607) | |

| Long-term indirect | −4.051 * (2.087) | −0.189 (1.344) | |

| Long-term total effect | −4.733 *** (1.495) | −0.529 (1.726) |

| R&D Output | Human Capital | Innovation Capacity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| logyfch | 0.690 *** (0.182) | ||

| logrlzb | 1.094 *** (0.338) | ||

| logcxsp | 0.177 (0.173) | ||

| peo | −0.299 (0.477) | −0.264 (0.468) | 0.0311 (0.724) |

| logm | 0.460 *** (0.0800) | 0.600 *** (0.0690) | 0.624 *** (0.162) |

| urban | 1.015 *** (0.192) | 1.028 *** (0.204) | −1.165 * (0.707) |

| fd | −0.305 ** (0.143) | −0.341 ** (0.156) | −0.0394 (0.239) |

| logfdi | 0.525 *** (0.0654) | 0.556 *** (0.0757) | 0.392 *** (0.0876) |

| dof | −0.358 *** (0.0738) | −0.449 *** (0.0775) | −0.0787 (0.0671) |

| Variable | Distance-Decay Effect | Spatial Proximity Effect | Spatial Heterogeneity Effect | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Long-Term Total Effect | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Long-Term Total Effect | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Long-Term Total Effect | |

| R | 6.385 *** (1.982) | −19.40 ** (8.187) | −13.01 (8.502) | 0.230 *** (0.0576) | 0.0502 (0.374) | 0.280 (0.383) | 0.0494 *** (0.0145) | 0.0501 (0.0980) | 0.0995 (0.100) |

| logdt | 0.531 *** (0.176) | 0.319 (0.990) | 0.850 (1.034) | 0.434 ** (0.179) | −0.581 (0.867) | −0.147 (0.914) | 0.457 ** (0.180) | −0.669 (0.854) | −0.211 (0.901) |

| peo | 0.712 ** (0.282) | 3.548 * (2.092) | 4.260 ** (2.171) | 0.524 * (0.290) | 4.930 ** (2.298) | 5.454 ** (2.377) | 0.559 * (0.293) | 4.466 * (2.478) | 5.026 ** (2.558) |

| logm | 0.558 *** (0.0552) | −0.0638 (0.0903) | 0.494 *** (0.101) | 0.482 *** (0.0584) | 0.0228 (0.102) | 0.505 *** (0.116) | 0.491 *** (0.0590) | 0.00235 (0.103) | 0.493 *** (0.118) |

| urban | 1.332 *** (0.240) | 0.297 (1.415) | 1.628 (1.475) | 0.948 *** (0.257) | −2.542 ** (1.120) | −1.594 (1.194) | 0.998 *** (0.259) | −2.719 ** (1.104) | −1.721 (1.179) |

| fd | −0.0536 (0.0844) | −0.00628 (0.274) | −0.0599 (0.294) | −0.133 (0.0858) | −0.163 (0.289) | −0.296 (0.312) | −0.128 (0.0863) | −0.146 (0.291) | −0.274 (0.314) |

| logfdi | 0.248 *** (0.0489) | −0.0521 (0.112) | 0.196 (0.124) | 0.247 *** (0.0480) | −0.00322 (0.119) | 0.244 * (0.133) | 0.247 *** (0.0482) | −0.00142 (0.120) | 0.246 * (0.134) |

| dof | −0.135 *** (0.0212) | −0.0698 (0.0604) | −0.205 *** (0.0640) | −0.140 *** (0.0211) | 0.0176 (0.0552) | −0.122 ** (0.0612) | −0.141 *** (0.0212) | 0.0287 (0.0575) | −0.112 * (0.0637) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, X.; Zeng, S. How Digital Technology Shapes the Spatial Evolution of Global Value Chains in Financial Services. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11229. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411229

Yu X, Zeng S. How Digital Technology Shapes the Spatial Evolution of Global Value Chains in Financial Services. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11229. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411229

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Xingyan, and Shihong Zeng. 2025. "How Digital Technology Shapes the Spatial Evolution of Global Value Chains in Financial Services" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11229. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411229

APA StyleYu, X., & Zeng, S. (2025). How Digital Technology Shapes the Spatial Evolution of Global Value Chains in Financial Services. Sustainability, 17(24), 11229. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411229