1. Introduction

Land prices form a central link between the housing market and the real economy. The land price circuit breaker has become a central instrument in China’s differentiated regulation of the residential land market, helping curb excessive land price volatility and supporting more sustainable land-use. Yet systematic academic research on this mechanism remains limited. Three questions naturally follow. The first concerns how its discrete trigger and rule-switching logic differ from traditional static price ceilings. The second asks whether the mechanism can restrain excessive land price increases and improve credit allocation through the collateral channel, and, if so, whether it can stabilize land price dynamics, ease credit misallocation, and enhance long-run macroeconomic performance. The third examines how the mechanism interacts with the central bank’s inflation-targeting framework, particularly through which endogenous channels a strict inflation target dampens housing prices and increases the likelihood of activation.

Residential land prices in major Chinese cities rose rapidly before and after the 2008 financial crisis. From 2006 Q1 to 2010 Q4, their average annual growth reached 26% (Chen and Wen, 2017) [

1]. Fast land price appreciation raised housing costs through higher construction costs and reduced the supply of affordable land. These pressures posed direct challenges to sustainable land-use. Speculative activity in the housing market also expanded mortgage borrowing. The household debt-to-income ratio jumped from 10% in 2006 to 56% in 2019. Rising leverage increased the risk of financial spillovers. Credit allocation also became increasingly distorted. Real estate lending rose excessively, raising financing costs for manufacturing firms and weakening the efficiency of resource allocation (Meng et al., 2019) [

2]. These patterns reflect deeper institutional features of China’s land system. The 1994 fiscal reform strengthened local governments’ reliance on land sales revenue. This reliance encouraged tighter land supply and strategic parcel design, which increased land premiums and strengthened the asset nature of residential land (Liu and Chen, 2020) [

3]. China’s dual urban–rural land system also grants local governments a monopoly over primary residential land auctions. This institutional arrangement provides a natural basis for policy intervention (Jiang et al., 2007 [

4]; Tan, 2014 [

5]). Against this backdrop, Suzhou and Nanjing introduced land price circuit breakers in 2016, and other major cities soon followed.

The land price circuit breaker is a dynamic price band used in residential land auctions. When bids reach the upper bound set by the government, the auction rules switch abruptly, providing immediate intervention against rapid land price increases. Its core features have two main components. First, the trigger price is not a fixed ceiling, but a flexible threshold based on benchmark land prices and past land price movements. When the mechanism is not triggered, the constraint remains slack, and land prices are fully determined by market forces. It becomes binding only after activation. Second, its operating logic differs fundamentally from a linear static price ceiling, which remains binding at all times (Weitzman, 1974 [

6]; Krysiak, 2008 [

7]). In contrast, the circuit breaker is a state-dependent rule with discrete activation. Its “off–on” switching mirrors the slack–bind structure of occasionally binding constraints in dynamic macroeconomics (Christiano and Fisher, 2000 [

8]; Guerrieri and Iacoviello, 2015 [

9]). Thus, the circuit breaker functions as a dynamic policy tool that responds endogenously to economic shocks rather than as a fixed price control instrument.

Limitations in the existing literature highlight the need for this study. Recent work examines static price floors for industrial land (Lin et al., 2020 [

10]; Wu et al., 2024 [

11]; Lin et al., 2024 [

12]; Tian et al., 2024 [

13]). No research analyzes a price ceiling for residential land, and no study identifies the state-dependent threshold and the discrete trigger that define the mechanism. Existing work also does not embed such a mechanism in a dynamic general equilibrium framework. Related empirical studies focus on the micro effects of industrial land price floors (Lin et al., 2020 [

10]; Tian et al., 2024 [

13]). They do not incorporate the monetary policy environment, leaving the cross-regional macroeconomic transmission unexplained. Global evidence shows that land prices account for about 80% of housing price fluctuations after World War II (Knoll et al., 2017 [

14]), and they remain the primary driver of housing price growth in China. Taken together, these facts imply that understanding the mechanism’s endogenous propagation and, in general, the equilibria are essential for evaluating housing market regulation and sustainable land-use outcomes.

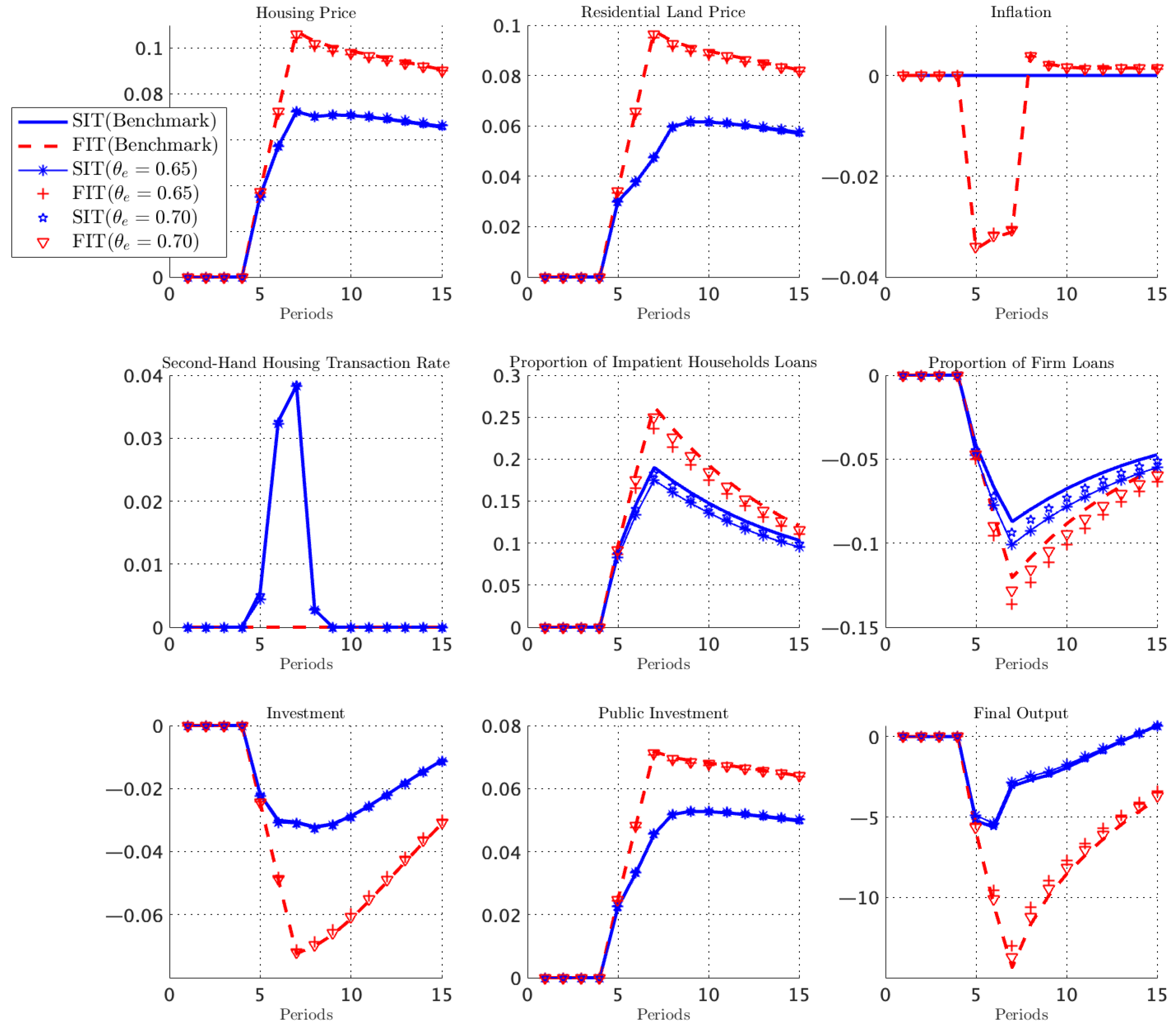

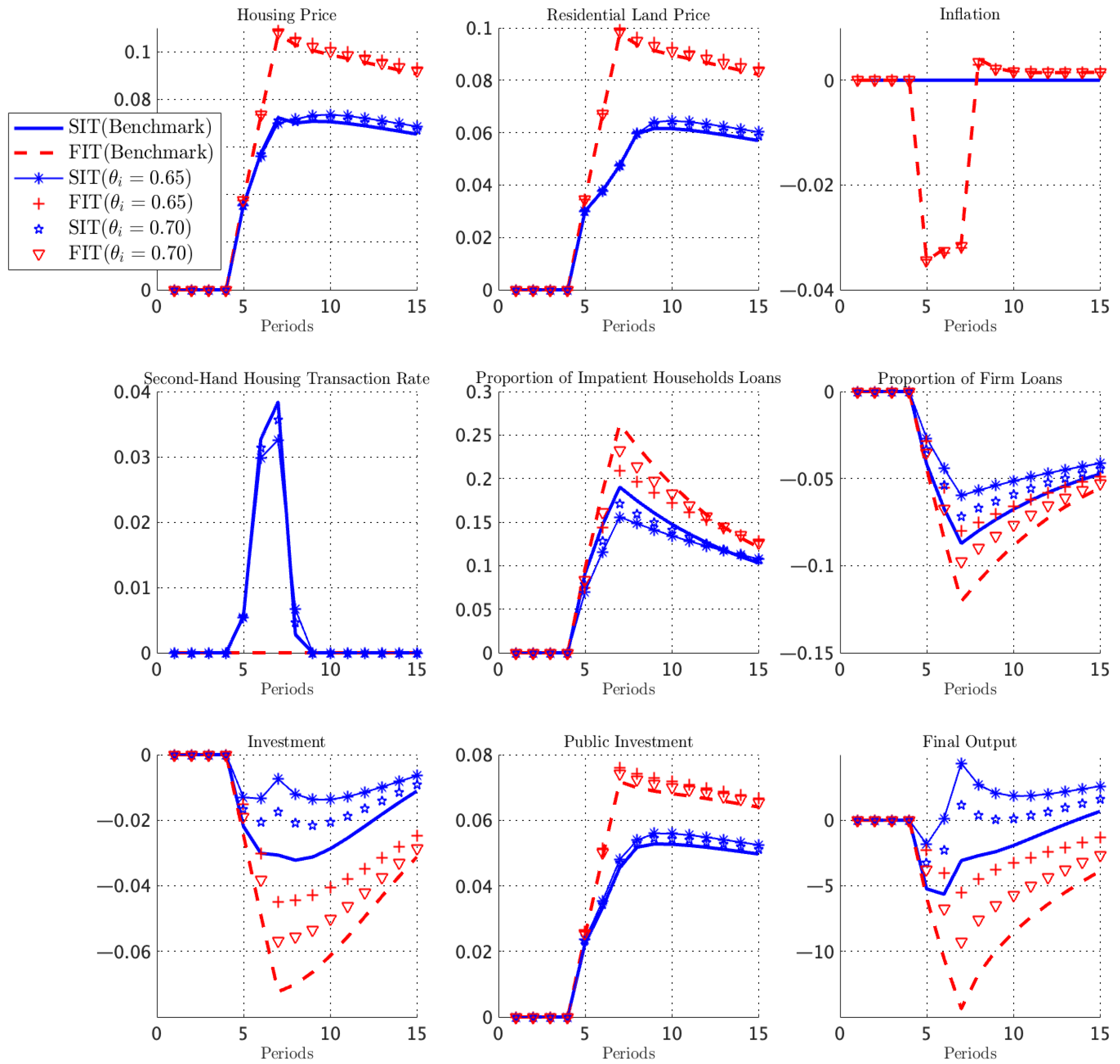

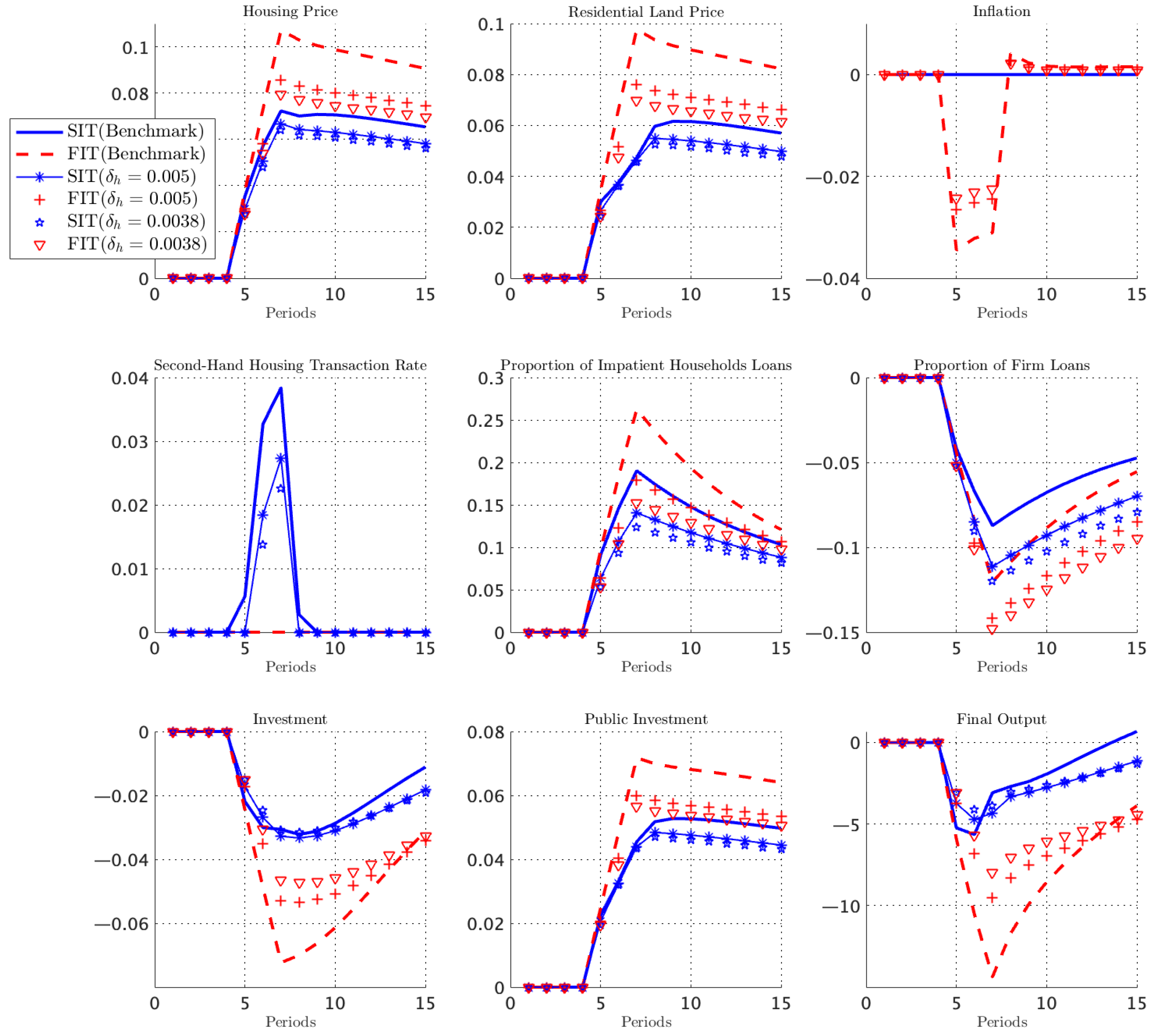

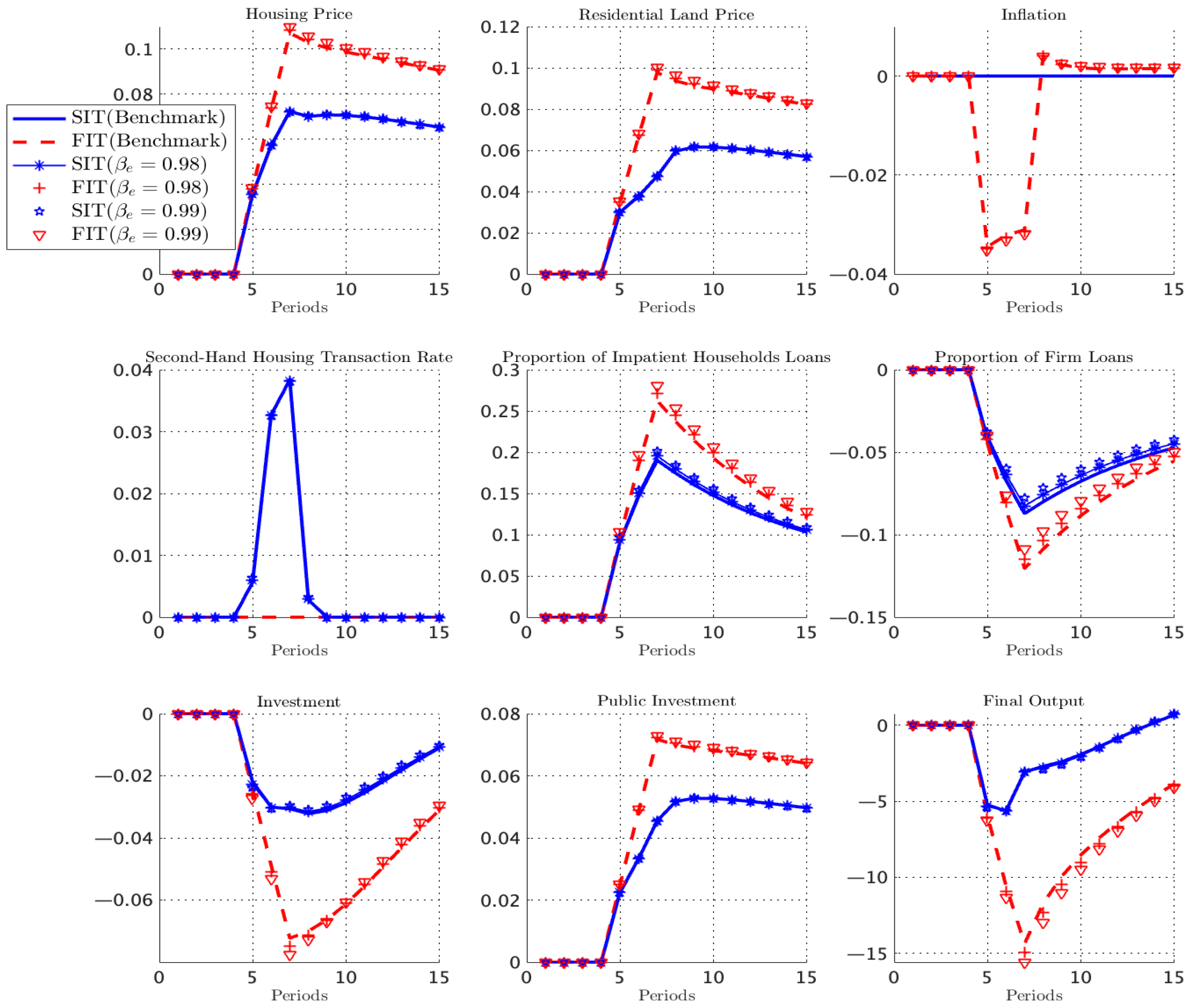

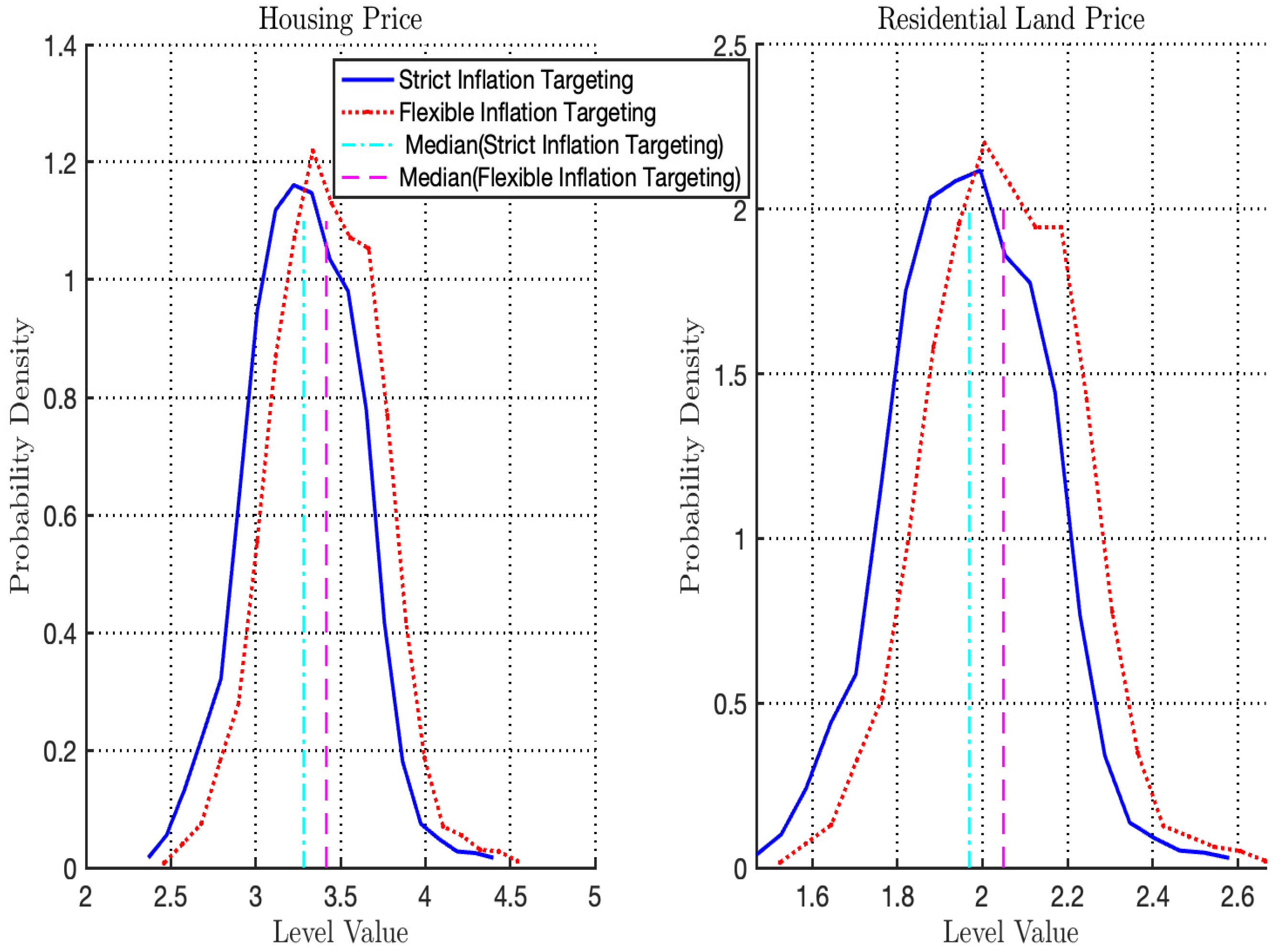

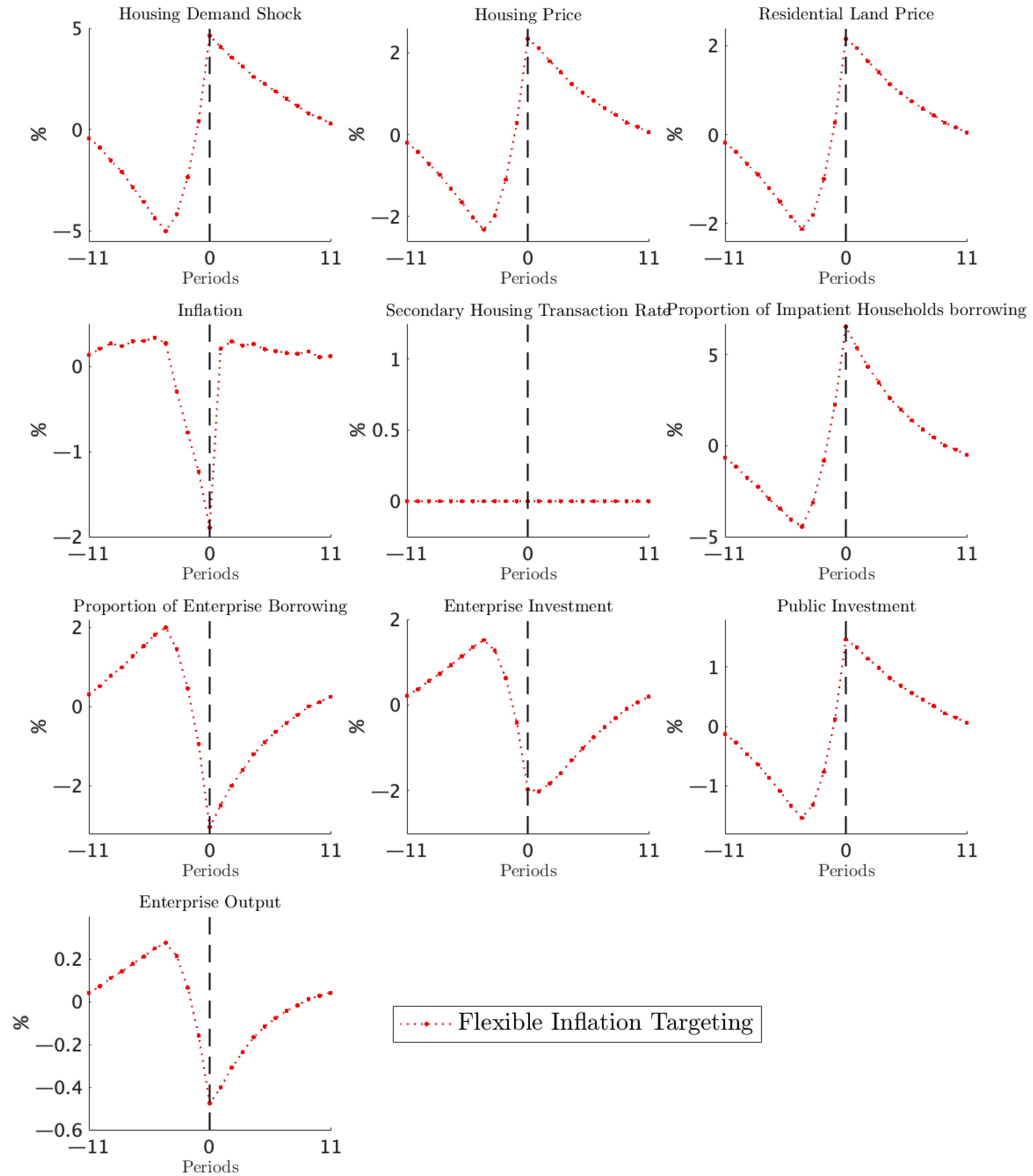

We fill this gap by developing a unified framework that incorporates local governments and land developers. Local governments set the price threshold, while developers demand land. We incorporate the mechanism’s dynamic threshold and discrete trigger into the DSGE model through an occasionally binding constraint. A positive housing-demand shock raises house prices, which pushes up land prices and activates the mechanism. We show that the trigger probability is zero under a flexible inflation target but rises to 9.74% under a strict inflation target. Under strict targeting, activation curbs land price growth, lowers land-sale revenue, and reduces local public investment. It also increases existing home transactions, limits house price increases, and restrains borrowing by impatient households. This shift raises the share of credit flowing to firms and mitigates credit misallocation. As a result, the contraction in firm investment and output is attenuated. Event analysis shows that strict targeting reduces land prices by 4.08% and narrows house price growth by 4.04%. Welfare improves because the mechanism dampens volatility, channels more credit toward productive firms, raises aggregate output, and supports higher consumption.

This study makes three theoretical contributions. First, it defines the land price circuit breaker as a mechanism with a dynamic threshold and a discrete trigger, grounded in observed policy practice. The model embeds this structure through a weighted price band and a trigger indicator. This design provides a verifiable institutional basis, resolves conceptual ambiguity in existing work, and offers an operational representation of government intervention through quantifiable price ranges and explicit trigger conditions. Second, this study uses an occasionally binding constraint to capture the switch between slack and binding states. This feature distinguishes the mechanism from traditional static price ceilings, such as those in Weitzman (1974) [

6] and Krysiak (2008) [

7]. The circuit breaker, therefore, functions as a dynamic regulatory tool that responds endogenously to macroeconomic shocks rather than as a fixed administrative cap. Third, this study develops a unified framework linking inflation targeting, land price regulation, credit allocation, and output. The framework shows how the central bank’s inflation target shapes the trigger probability and how changes in collateral values and credit flows propagate to firm investment and final output. It provides quantitative evidence on the interaction between local land policies and national monetary policy.

The structure of this study is as follows:

Section 2 presents the literature review.

Section 3 introduces the model’s specific construction.

Section 4 focuses on parameter calibration and estimation.

Section 5 presents the results of numerical simulations and mechanism analysis.

Section 6 assesses the volatility of the major variables and analyzes agents’ social welfare.

Section 7 concludes with the main findings and implications.

2. Literature Review

Land price regulation is a core component of China’s factor price control system. It has attracted growing academic attention. Yet the macroeconomic effects of dynamic price regulation for residential land remain largely unexplored. This study engages closely with the central literature on land price regulation. It advances the field through new analytical perspectives, new policy tool design, and new mechanisms of transmission.

The first strand is the foundational literature on price regulation, represented by Weitzman (1974) [

6]. His classic study compares price-based and quantity-based instruments but focuses on a single-period static setting. Such a setting offers limited policy flexibility. It works when market volatility is low and policy objectives are simple, but it cannot accommodate the highly volatile and multi-market nature of residential land prices. Krysiak (2008) [

7] extends this framework by incorporating firms’ technology choices. He shows that price regulation can distort long-run investment decisions. It may push firms toward safer but socially inferior technologies. Bulow and Klemperer (2012) [

15] analyze how price ceilings affect consumer surplus and welfare through misallocation and rent-seeking. They emphasize that static price ceilings can reduce efficiency even in the absence of quantity restrictions. Prest and Pizer (2019) [

16] respond to this limitation by proposing “policy updating”, which allows regulators to revise price or quantity controls over time. Their results show that dynamic adjustments can reduce misallocation and enhance policy flexibility. They also find that dynamic price regulation is often more robust than quantity regulation under imperfect information or suboptimal government behavior. Taken together, these studies present a clear logic: static controls lead to efficiency losses, while dynamic adjustments offer a path to improvement. The broader lesson is that price regulation affects more than price levels. It also shapes behavioral incentives and investment decisions, which alter resource allocation. This insight motivates a dynamic mechanism such as a land price circuit breaker. The mechanism stabilizes land price volatility and mitigates distortions in resource allocation.

A second strand of research examines price regulation in China’s industrial land market. Key contributions include Lin et al. (2020) [

10], Wu et al. (2024) [

11], Lin et al. (2024) [

12], and Tian et al. (2024) [

13]. Lin et al. (2020) [

10] studied minimum-price rules for industrial land. These rules raise micro-level efficiency by screening out low-productivity firms and reducing idle land. Wu et al. (2024) [

11] find that minimum-price policies weaken firms’ positions in the global value chain. Their analysis remains local and partial-equilibrium in nature. Lin et al. (2024) [

12] show that industrial land protection in Guangdong improves allocation efficiency by tightening price constraints and restricting low-priced supply. This mechanism also complements the objectives of the price-floor policy. Tian et al. (2024) [

13] examine the 2007 reform of the industrial-land market. They show that improved auction design and binding minimum prices together enhanced allocation efficiency. However, this strand of the literature focuses only on industrial land. This study departs from it by studying residential land, which functions both as a productive input and as an asset. Residential land is highly sensitive to expectations and credit conditions. It displays greater volatility and stronger demand elasticity than industrial land. These features shape credit allocation and household leverage, ultimately influencing macroeconomic stability. These conditions, therefore, call for a regulatory tool that adjusts flexibly to shocks. This study goes beyond existing micro-empirical studies of price floors. It develops a structural general equilibrium framework to analyze how the land price circuit breaker affects credit allocation and aggregate welfare. This structural approach allows the mechanism’s general equilibrium and macroeconomic consequences to be evaluated in ways that existing empirical studies cannot.

A third strand of research studies price ceilings in the residential housing market, with Zhou (2025) [

17] providing the most relevant contribution. Zhou (2025) [

17] shows that Shanghai’s new-home price cap lowered transaction prices. However, the static ceiling became misaligned with market fundamentals; excess demand was allocated through lotteries, creating waiting costs and misallocation. These frictions generated a net welfare loss. Both Zhou (2025) [

17] and this study find that price regulation can suppress prices. Yet their policy designs and transmission mechanisms differ fundamentally. Zhou (2025) [

17] analyzes a fixed, passive ceiling that does not incorporate market dynamics or their interaction with monetary policy. In contrast, this study studies a state-dependent circuit breaker with active adjustment. The mechanism sets a dynamic price band using historical land price information and ties the activation condition to the central bank’s inflation-targeting rule. This design avoids price distortions, reallocates credit from impatient households to non-real estate firms, and improves resource allocation, thereby offsetting the welfare losses associated with static caps. These differences in institutional structure lead to contrasting welfare implications in Zhou (2025) [

17] and in this study.

From a modeling standpoint, the land price circuit breaker is best interpreted as an operational instance of an occasionally binding constraint (OBC) in the land-regulation context. The OBC literature in dynamic macroeconomics can be organized into methodological contributions and applied developments. On the methodological side, early research provides the core analytical tools. Blanchard and Kahn (1980) [

18] derive existence and uniqueness conditions for linear rational expectations models, although these conditions do not allow for regime switching. Christiano and Fisher (2000) [

8] use dynamic programming to characterize nonlinear structures, but the approach is computationally intensive. Jung et al. (2005) [

19] propose a piecewise solution over state-dependent regions, although the timing of the constraint must be imposed exogenously. A key methodological advance is provided by Guerrieri and Iacoviello (2015) [

9], who introduce the OccBin toolkit and implement a tractable piecewise-linear perturbation method. A parallel line of work applies OBC structures to different macroeconomic environments. Zeldes (1989) [

20] studies consumption under borrowing constraints that bind occasionally. Abel and Eberly (1999) [

21] use a similar structure to examine investment adjustment frictions. Eggertsson and Woodford (2003) [

22] embed state-contingent constraints in a New Keynesian model to analyze the zero lower bound. Despite these advances, this research program focuses on standard macroeconomic settings—consumption, investment, and monetary policy—and typically features relatively simple agent behavior. The applicability of OBC methods to complex factor markets, such as residential land, remains largely unexplored.

This study extends the OBC framework to the land market and advances both its technical and applied dimensions. First, on the applied side, it addresses a key limitation of standard OBC applications, which are typically confined to environments without asset-price dynamics or credit constraints. It brings the framework into a system in which asset prices, credit flows, and policy interventions interact. It embeds the policy trigger rule into the interacting mechanisms of land supply and the housing market. Second, on the modeling side, it designs a price ceiling trigger that captures the strong heterogeneity, cross-sector spillovers, and high volatility of land prices. This structure preserves the complementarity conditions of OBCs while matching the distinctive dynamics of the land market. Third, on the analytical side, it embeds OBCs within a general equilibrium framework that includes households, financial intermediaries, real estate firms, and the land market. Using numerical simulations, it evaluates the general equilibrium effects on credit allocation, household leverage, and social welfare. This approach fills a major gap in applying OBC methods to factor-market regulation.

This study also builds on research that links inflation targeting to DSGE applications in land and housing markets. The first strand studies monetary policy rules and nominal anchors. The second examines the dynamic interactions among land prices, housing markets, and the macroeconomy. This study integrates these perspectives to analyze how the central bank’s inflation target shapes the activation and transmission of a land price circuit breaker, in general, equilibrium. The inflation-targeting literature shows that the target influences nominal-rate space, policy effectiveness, and expectation formation. Blanchard et al. (2010) [

23] argue that higher steady-state inflation can ease policy constraints near the lower bound. Coibion et al. (2012) [

24] find that the optimal target may lie below 2%, highlighting model dependence. Svensson (1997) [

25], Bernanke and Mishkin (1997) [

26], and Gürkaynak et al. (2010) [

27] provide theoretical foundations for time inconsistency and nominal anchoring. DSGE research on land and housing emphasizes amplification through collateral constraints, credit expansion, and asset price dynamics. Kiyotaki and Moore (1997) [

28] develop the canonical collateral transmission mechanism. Iacoviello (2005) [

29] endogenizes housing and household credit constraints. For China, Guo et al. (2015) [

30] show that reliance on land finance amplifies housing prices and macroeconomic fluctuations. Chen and Wen (2017) [

1] identify the forces behind China’s housing boom. Jiang et al. (2021) [

31] demonstrate that real estate bubbles and land sale revenues influence public investment and long-run growth. The contribution of this study differs from these studies in three ways. First, it endogenizes the circuit breaker by modeling land prices as the endogenous trigger variable for activation. Second, it integrates inflation targeting, land prices, and local government behavior into a unified framework to show how these mechanisms jointly shape macroeconomic dynamics. Third, it uses a dynamic DSGE model to connect policy actions to asset price dynamics, providing a structured analysis of policy transmission.

Existing research focuses primarily on monetary policy rules, housing collateral constraints, land finance, and property taxation. Far less attention has been given to local land price regulations, including residential land price ceilings and circuit breakers, and to their interaction with macroeconomic policy. In China’s land auction system, these tools are activated frequently. Yet DSGE models have not incorporated them endogenously or examined how inflation targeting affects the conditions under which the mechanism is triggered. Given China’s fiscal dependence, scarcity, and heavy regulation, land prices are jointly shaped by policy and economic conditions. The channels through which inflation targets influence circuit breaker activation and its macroeconomic consequences remain unclear. This study fills this gap by developing a DSGE framework that integrates inflation targeting with local land price regulation. It then analyzes how macro policy affects circuit breaker activation, land supply, and the transmission of credit and leverage.

3. Model Construction

Our model is grounded in the structural framework established by the classical housing-market literature, most notably Kiyotaki and Moore (1997) [

28], Iacoviello (2005) [

29], and Liu et al. (2013) [

32]. This model is a multi-sector DSGE framework with an embedded land price circuit breaker. It contains six sectors. The local government monopolizes residential land supply and implements the circuit-breaker rule. The central bank sets the inflation target. The patient household saves through deposits, while the impatient household borrows against housing collateral. Both household types hold housing assets and trade in the secondary-housing market. Housing enters their utility and provides residential services. The entrepreneur borrows against capital and hires labor from households. The entrepreneur produces output with capital, labor, and public capital. Public capital raises firm productivity through positive externalities. The developer purchases residential land from the local government and constructs new housing. The developer determines land demand, while the local government determines land supply. The model features five markets. These include the land market, the new housing market, the secondary-housing market, the credit market, and the final-goods market. Together they form a linked system of land prices, housing prices, credit flows, and output. The circuit breaker is formalized as an occasionally binding constraint. It is implemented through the OccBin algorithm of Guerrieri and Iacoviello (2015) [

9]. The constraint switches between inactive and activated states. This structure differs from a static land price ceiling. The mechanism imposes a dynamic upper bound on land prices, defined relative to historical land price movements. A housing-demand shock raises housing prices and then increases land prices. The circuit breaker activates when land prices hit the upper bound. Activation reduces land supply and new housing construction. It also shifts transactions toward the secondary-housing market. Under inflation targeting, credit allocation adjusts. This adjustment increases the credit share available to the entrepreneur. It also mitigates macroeconomic fluctuations. The model quantifies how alternative inflation targets influence land prices, output volatility, and welfare under the circuit breaker. It provides analytical support for housing-market regulation and macro-policy coordination.

Figure 1 presents the structure of the model.

3.1. Patient Households

The utility function of patient households is

Equation (1) adopts a standard separable utility specification used in the housing model of Iacoviello (2005) [

29]. The first component captures consumption, the second captures housing services, and the third captures labor supply. Consumption and housing services provide positive utility to the household, while labor supply generates negative utility. This paper focuses on the effects generated by changes in housing services. Equation (1) involves the expectation operator

.

represents the subjective discount factor of patient households.

denotes the persistence parameter of patient households’ consumption habits.

is the consumption of patient households.

represents the housing demand shock of patient households.

denotes the new houses held by patient households in the current period, which provide residential services.

denotes the weight of labor supply.

represents the labor supply of patient households.

represents the scale factor.

denotes the intertemporal substitution elasticity of labor supply for household units. It is assumed that the housing demand shock of patient households follows the process

:

() represents the persistence coefficient of the process . denotes the steady-state value of the housing demand shock of patient households. represents a sequence of independent and identically distributed standard normal processes. denotes the standard deviation of the housing demand shock.

The budget constraint for patient households is formulated as follows:

Equation (3) states the household budget constraint. The right-hand side represents household income, and the left-hand side represents household expenditures. Income includes labor income, the gross return on risk-free bonds, and the lump-sum profit transfers from the secondary-housing market and real estate developers. Expenditures include consumption, housing holdings, and bond holdings. In Equation (3), represents the nominal price of housing. denotes the second-hand house held by patient households after depreciation. represents the depreciation rate of housing. Define as inflation, as the nominal wage rate, and as the nominal price of consumption goods. represents the lump-sum profits transfer obtained by patient households from the secondary housing market. denotes the real price of bonds held by patient households. Assume patient households react to the land price circuit breaker, releasing some second-hand housing into the market when triggered. The proportion of second-hand houses sold is denoted by . represents the proportion supplied by patient households in the second-hand housing market. indicates the time-varying responsiveness of patient households to the land price circuit breaker mechanism. is the indicator function, in which denotes the nominal price of the residential land. The indicator function is 1 if the circuit breaker mechanism is triggered in the current period, and 0 if it is not. represents the risk-free bonds held by patient households in the current period. represents the lump-sum profits transfer obtained by patient households from housing developers.

3.2. Impatient Households

The utility function of impatient households is expressed as

The economic interpretation of Equation (4) closely parallels that of Equation (1). From Kiyotaki and Moore (1997) [

28], we know that credit flows from the patient household to the impatient household. Whether a household is patient or impatient depends on its subjective discount factor. In Equation (4),

denotes the subjective discount factor for impatient households, which is smaller than

. Here,

represents the consumption of impatient households.

represents the ownership of new houses by impatient households. Impatient households derive housing services in the current period through the possession of new houses.

signifies the labor supply of impatient households.

denotes the scale factor.

represents the persistence parameter for the consumption habits of impatient households, and

represents the weight on their labor supply.

The budget constraint for impatient households is formulated as follows:

The economic interpretation of Equation (5) is similar to that of Equation (3). The difference lies in the second income component, which represents borrowing obtained from the patient patient household. In Equation (5), represents the second-hand houses held by impatient households after depreciation. Let denote the proportion of second-hand housing sold by impatient households, and the share of impatient households in the second-hand housing market. signifies the time-varying reflection degree of impatient households on the land price circuit breaker mechanism. represents the loans of impatient households. denotes the nominal wage rate. Similarly to patient households, represents the lump-sum profits transfer that impatient households obtain from the second-hand housing market. Additionally, signifies the lump-sum profits transfer acquired by impatient households from housing developers.

Impatient households, when borrowing from the credit market, encounter the following form of credit constraint

where

is the real price of housing. Due to credit constraints, the mortgage value of housing affects impatient households’ borrowing capacity.

signifies the loan-to-value ratio. Equation (6) carries the same economic interpretation as the credit constraint in Kiyotaki and Moore (1997) [

28]. The impatient household faces a borrowing limit tied to a fixed fraction of its housing value. This constraint indicates that the impatient household borrows from the patient household using housing as collateral. If repayment fails, the patient household can seize the collateral. Because the loan is strictly below the collateral value, the patient household incurs no loss. This condition guarantees the patient household’s incentive to supply credit.

3.3. Representative Entrepreneur

As in Liu et al. (2013) [

32], we assume that the entrepreneur maximizes expected utility and derives utility solely from consumption. The utility function form of the representative entrepreneur is expressed as follows:

In Equation (7), represents the consumption of entrepreneur, where is the parameter capturing the sustained habits of consumption, and is the subjective discount factor of the entrepreneur. Assuming that ; signifies the scale factor.

Our production function differs from the specifications in Iacoviello (2005) [

29] and Liu et al. (2013) [

32]. We introduce public capital, which is absent from their formulations. Public capital is supplied by the local government and generates positive externalities for firm production. Unlike private capital, it cannot be chosen endogenously by the firm. The production function form for the representative entrepreneur is expressed as follows

where

represents the proprietary capital of representative entrepreneurs, while

and

denote the labor employed by entrepreneurs from patient and impatient households.

denotes the final output of the enterprise.

represents the share of labor supplied by patient households to the firm’s production, while

represents the share supplied by impatient households to the firm’s labor force.

represents the overall share of employed labor in the production process.

.

represents the share of public capital stock provided by local governments.

denotes the proportion of public capital stock provided by local governments for firm production.

refers to total factor productivity. Assuming that

follows an

process:

where

is a sequence of independently and identically distributed standard normal processes, and the decay coefficient of the process

is

.

represents the standard deviation of technological shocks.

The evolution equation for the private capital is as follows:

where

is the parameter of private capital adjustment costs, and

is the depreciation rate of private capital. Equation (10) adopts the standard investment-adjustment-cost specification used in Liu et al. (2013) [

32].

The budget constraint for the entrepreneur is expressed as follows:

where

represents the entrepreneur’s investment, and

denotes the tax rate on income tax paid by non-real estate enterprises to local governments. The right-hand side of Equation (11) consists of after-tax revenue, wage payments to patient and impatient households, and borrowing from the patient household. The left-hand side consists of entrepreneurial consumption, firm investment, and the gross repayment to the patient household.

Entrepreneurs face the following credit constraints:

where

is the total loans borrowed by entrepreneurs, and

is the shadow price of private capital relative to consumption goods.

represents the nominal shadow price.

indicates the loan-to-value ratio, which compares the value of loans to entrepreneurial credit constraints. The credit constraint in Equation (12) is economically analogous to the impatient household’s constraint in Equation (6). However, Equation (12) assumes that the entrepreneur pledges private capital as collateral. This specification departs from Kiyotaki and Moore (1997) [

28] and Iacoviello (2005) [

29], who assume land as collateral. In our framework, the entrepreneur holds no housing assets. Consequently, access to credit requires pledging private capital.

3.4. Department of New Housing Construction

3.4.1. New Housing Construction

In line with Garriga et al. (2021) [

33], developers are assumed to operate a specific technology

that transforms residential land into final housing units. In this case, the production function for this department can be expressed as follows:

where

represents the quantity of residential real estate developed by the department in the current period.

denotes the land required for residential construction by the department.

represents the input elasticity of residential land in real estate development.

The objective function for this department is formulated as follows:

where

represents the nominal profit of the real estate firm, and

is the nominal price at which the real estate developer acquires one unit of residential land. From Equation (14), the developer solves a purely static, one-period optimization problem. This implicitly assumes that developers live for only one period and are replaced by new entrants in the next period. The purpose of this assumption is to rule out land hoarding. If developers were allowed to optimize intertemporally, they could accumulate sufficient land over time and eventually cease purchasing land from local governments.

3.4.2. Secondary Housing Market

In the economic system, there exists a secondary housing market where the total transaction volume of existing residential properties in each period is denoted by , leading to . This paper assumes that the residential services of existing housing in the secondary market are homogeneous with those of newly constructed housing. Sellers in the existing housing market incur a certain proportion of transaction costs. Therefore, it is assumed that transaction costs constitute a proportion of the total value of secondary housing. Accordingly, represents the lump-sum profit patient households receive from selling secondary housing, after transaction costs. Similarly, denotes the lump-sum profit received by impatient households from selling secondary housing, after transaction costs. Simultaneously, it is assumed that represents the time-varying sensitivity of patient households to the land price circuit breaker mechanism. Similarly, represents the time-varying response of impatient households to the land price circuit breaker mechanism. represents the current period’s land supply by the local government.

3.5. Local Government

The equation for the local government’s public capital investment is

The left side of Equation (15) represents the fiscal revenue of the local government. Here, denotes the tax paid by real estate developers to the local government, and is the tax rate. The source of public capital investment is the fiscal revenue of the local government. The real price paid by real estate developers for one unit of residential development land is , where . The local government’s land supply is denoted by , while its land supply function is represented by . In this function, represents the sensitivity of residential land supply to preference shocks in housing demand.

denotes the supply of residential land by the local government in a steady state. In the land market, the land supply function is private information of the local government. Therefore, the development department knows the current quantity of residential land supplied by the local government, but cannot observe the exact form of the land supply function.

The equation for the accumulation of public capital by the local government is

Here, represents the depreciation rate of public capital, and represents the parameter for the adjustment cost of public capital.

The local government exercises monopoly power in the primary residential land market and, due to recurring ‘three highs’ land parcels (high total price, unit price, and premium), must regulate land prices. The local government’s land market controls are reflected in the circuit breaker mechanism that regulates residential land prices. The land price circuit breaker constitutes a vital element of sustainable land-use policies. This mechanism suppresses speculative activities in land markets and enhances the efficient allocation of land resources. In this mechanism, the local government sets a price range for residential land and engages in transactions with the real estate development sector. In this context, we assume

, where

represents the weighted historical land prices prior to the current period (

), and

represents the weight assigned to the land price in period

. The parameter

represents the historical periods considered by the local government. For instance, if

equals 16, this indicates that the government uses historical land prices over the past 16 periods, with each period representing one quarter (equivalent to four years in total). Thus, the circuit breaker range for land prices is given by

Land prices, land demand, and land supply satisfy the following conditions:

Equation (18) shows that a negative shock to housing demand causes the residential land price to fall and reach the lower bound of the circuit breaker range. As a result, the demand for residential land falls below its supply. Similarly, Equation (19) shows that a positive shock causes the land price to rise, reaching the upper bound of the circuit breaker range. As a result, land supply falls short of demand. The land price circuit breaker is an application of an Occasionally Binding Constraint (OBC) in land price regulation. OBCs describe state-dependent and asymmetric policy rules in dynamic macroeconomics. The constraint binds only when the variable reaches a threshold and stays slack otherwise. An OBC uses an inequality constraint, a Lagrange multiplier, and a complementary-slackness condition to show when intervention becomes active. When the variable crosses the threshold, the multiplier becomes positive and the constraint tightens. When the variable stays below the threshold, the multiplier is zero and the economy follows the unconstrained path. OBCs capture switches between market allocation and policy intervention, making them suitable for trigger-based tools. The land price circuit breaker follows exactly this structure. The land price ceiling acts as a state-dependent constraint. If market prices remain below the ceiling, the constraint is slack, and land allocation is market-driven. Once the ceiling is reached, the constraint binds, the multiplier turns positive, and intervention begins. Thus, the circuit breaker is the institutional form of an OBC in land price regulation.

3.6. Market Clearing and Equilibrium Definition

3.6.1. Market Clearing and Equilibrium

- 1.

The market clearing conditions for the final goods

The clearing condition of the final goods market is as follows

- 2.

The market clearing

The market clearing conditions for the housing market are represented by Equations (21) and (22):

In Equation (21),

represents the total demand for housing in the current period.

In Equation (22), represents the housing development quantity by the real estate department, and represents the transaction volume of second-hand housing.

- 3.

Credit market clearing conditions

The clearing conditions for the credit market are expressed as follows:

- 4.

The nominal profit distribution of the real estate development department

In the above equation, note that , and . and represent the proportions of nominal profits from real estate development transferred as lump sums to patient and impatient households, respectively.

3.6.2. The Definition of Competitive Equilibrium

In the context of the provided price sequences , exogenous shock processes , and endowment processes , the competitive equilibrium is defined as the state in which entrepreneurs, patient households, and impatient households maximize utility, while real estate developers maximize profits. This equilibrium is subject to three constraints: credit, budget, and market clearing.

3.7. Occasional Triggering of the Land Price Circuit Breaker

Proposition 1. Under the central bank’s strict inflation targeting (), sufficiently large exogenous housing demand shocks can activate the land price circuit breaker.

Proof of Proposition 1. Temporal consistency in the central bank’s strict inflation-targeting policy implies that inflation remains at the target in each period. Therefore,

In scenario 1, when

,

It is also evident in scenario 2 that when

, defining

,

Similarly, it can be demonstrated that

In conclusion, under the central bank’s strict inflation targeting, the local government’s land price circuit breaker mechanism is equivalent to . When the central bank strictly targets inflation, the nominal residential land price may reach the upper and lower bounds of the circuit breaker. Under the central bank’s strict inflation targeting, the land price circuit breaker may trigger. □

Proposition 1 states that strict inflation targeting sharply reduces the scope for nominal price adjustment. Under this regime, the nominal anchor is fixed because nominal interest rates move one-for-one with inflation. Shocks to housing demand must, therefore, be absorbed by real prices. Higher housing demand raises house prices, which increases developers’ demand for land and puts upward pressure on land prices. With inflation held at its target, the economy cannot rely on nominal adjustment to absorb the shock. The entire burden falls on the relative price of residential land. This shift makes it more likely that land prices press against the upper bound of the policy band. The intuition parallels the mechanism at the zero lower bound: a nominal constraint forces the real side of the economy to absorb shocks. Strict targeting compresses the nominal margin of adjustment to zero. Once a housing demand shock becomes sufficiently large, the land price ceiling becomes a likely binding constraint. This shift turns the event of hitting the ceiling from a low-probability outcome into a state-dependent one. A general equilibrium channel reinforces this pattern. Housing demand shocks raise collateral values, expand credit, and increase developers’ land demand. When inflation cannot rise with the shock, excess demand concentrates on land prices alone, increasing the probability of hitting the circuit breaker threshold. Proposition 1, thus, highlights a central policy implication: the nominal anchor chosen by the central bank determines how likely land prices are to reach their ceiling. It also reveals a fundamental interaction between strict inflation targeting and the activation of the land price circuit breaker.

Proposition 2. In a dynamic economy subject to large positive or negative shocks to housing demand, the central bank’s inflation-targeting rule ensures that the gross inflation rate satisfies (for negative shocks), where is the real price growth rate of residential land and . Under these conditions, the land price circuit breaker will not be triggered.

Proof of Proposition 2. The land price circuit breaker has not been triggered, indicating that the price of residential land cannot reach the circuit breaker bounds. Since

and

, we have

. Hence,

In this statement,

(

) denotes the central bank’s inflation response coefficient. Therefore, when a dynamic economic system faces a positive housing demand shock, the inflation rule is:

In Equation (31), allowing the parameter to take values in the feasible domain yields a set of inflation rules. When , the gross inflation rate is maximized, denoted by . Alternatively, if , the gross inflation rate is . From this, it can be inferred that . Therefore, if the central bank’s inflation target ensures that , the nominal price of residential land will not reach the upper bound.

Similarly, when a dynamic economic system faces a negative shock to housing demand, it follows the inflation rule:

In Equation (32), and function similarly. In this scenario, as long as the central bank’s inflation target ensures the inflation rate is , there is no possibility of the nominal price of residential land hitting its lower bound. Therefore, when the dynamic economic system faces an adverse shock to housing demand, implementing appropriate inflation policies by the central bank ensures that holds. In such circumstances, the land price control limits and circuit breaker will not be triggered. This means the nominal land price will never hit the limits of the circuit breaker. □

Proposition 2 states that nominal land prices will not hit the circuit breaker bounds under either positive or negative housing demand shocks. This outcome holds when the central bank adopts a sufficiently flexible inflation target. A flexible target allows inflation to adjust in response to shocks, preventing nominal land prices from reaching either boundary and keeping the circuit breaker inactive. The intuition is straightforward. Flexible inflation targeting turns nominal adjustment into a buffer. When monetary policy allows some nominal movement, part of the demand pressure is absorbed by inflation rather than by land prices. As a result, nominal land prices do not bear the full adjustment burden. Under a positive housing demand shock, the central bank allows inflation to rise. This adjustment reduces the pressure on nominal land prices to fully reflect the increase in real demand. Under a negative shock, a moderate decline in inflation prevents nominal land prices from falling rapidly toward the lower bound. General equilibrium forces reinforce this mechanism. Higher housing demand raises house prices and increases developers’ demand for land. If inflation can rise with the shock, the pressure on real land prices diminishes and the upper bound does not become binding. If inflation is fixed, however, the entire real pressure falls on land prices, sharply increasing the probability of hitting the ceiling. Proposition 2, therefore, shows that the flexibility of monetary policy determines whether a price-based regulatory tool such as the circuit breaker enters its activation region. Flexible inflation targeting and the state-dependent land price constraint are complementary. Greater monetary flexibility makes activation less likely, while a stricter nominal anchor raises the likelihood of binding episodes.

Propositions 1 and 2 analyze the conditions under which the residential land price reaches the circuit breaker limits, given different inflation rules set by the central bank (Equation (17)). Equation (17) can be transformed into an inequality by introducing inflation (considering only the upper bound, with a similar argument for the lower bound), i.e., . If equality is possible in the inequality, it can be determined whether equality holds in . In Proposition 2, Equation (31) specifies the inflation rules preventing the nominal price of residential land from reaching its upper bound. These inflation rules correspond to a category of monetary policies. If these policies ensure in response to positive shocks to housing demand, the circuit breaker’s upper bound will never be triggered. Since , this inflation rule category encompasses several inflation targets. In practice, these policies may align with those implemented in the real world.

Figure 2 shows the set of feasible inflation targets with

in response to positive shocks to housing demand. As long as the central bank’s inflation target ensures the net inflation rate remains within this set, the upper bound of the land price circuit breaker will not be triggered.

Figure 2 shows that as the real price growth rate of land increases, the set of feasible inflation targets gradually narrows.

4. Parameter Calibration and Estimation

The paper classifies parameters into three groups based on the distinct characteristics of the internal model. Parameters are calibrated and estimated individually based on real-world data. Deep structural parameters such as

are included in Group 1. Each period is a quarter, and parameters are calibrated using Chinese data as well as empirical and theoretical studies on China’s real estate market. For instance, according to Dong et al. (2021) [

34], the subjective discount rate of patient households, denoted as

, implies a quarterly steady-state real interest rate of 0.5%. Dong et al. (2021) [

34] estimate China’s annual real interest rate at roughly 2% by deflating nominal household deposit rates over 2000–2016. The subjective discount rates,

for impatient households and

for entrepreneurs, follow Iacoviello and Neri (2010) [

35]. The loan-to-value ratio,

, for impatient households implies a 25% down payment. A 25% down-payment ratio is broadly consistent with current Chinese mortgage requirements. In the production function of non-real estate firms, the elasticity of labor supply

is 0.5, which characterizes China’s labor-intensive non-real estate industries, as found by Song et al. (2011) [

36]. This value is consistent with empirical evidence from China. The labor income share for patient households,

, is consistent with Guerrieri and Iacoviello (2017) [

37]. The parameter

is consistent with Baxter and King (1993) [

38]. Following Liu et al. (2013) [

32], the loan-to-value ratio

, representing credit constraints for entrepreneurs, is set at 0.75. Following Iacoviello and Neri (2010) [

35], the annual depreciation rate of entrepreneurs’ capital is assumed to be 10%. This implies a quarterly depreciation rate of 0.025 (

) for entrepreneurs’ private capital. This is consistent with the depreciation rate estimated for China by Bai et al. (2006) [

39]. The annual depreciation rate of residential real estate is set at 4% based on Iacoviello and Neri (2010) [

35], yielding the quarterly depreciation rate

for housing. This value implies a housing replacement cycle of about 25 years in China. According to Jin (2016) [

40], the depreciation rate

for local government public capital is determined. Jin (2016) [

40] finds that the depreciation rate of public capital in China is similar to that of private capital. In line with Guerrieri and Iacoviello (2017) [

37], the parameter

is set to 1. We set

to match the share of land in residential construction costs in China’s first-tier cities, which typically ranges from 39% to 65% and exceeds 65% in some cases. Real estate developers face multiple tax obligations, including the deed tax, stamp duty, the urban construction and maintenance tax, the land-use tax, and the farmland occupation tax. We combine these taxes to calculate

. Following Devereux and Yu (2019) [

41], the proportions of patient and impatient households in the real estate sector’s lump-sum profit transfer are set to be equal, with

and

. Second-hand housing transactions involve various taxes and fees, including the deed tax, stamp duty, transaction charges, survey fees, and agent commissions. The total cost of these fees is estimated at 5% of the transaction value, i.e.,

. This paper assumes the proportion of patient households in the second-hand housing market is

. This assumption reflects that impatient households must collateralize housing to satisfy their demand, which leads to a lower housing transaction rate than that of patient households. The specific values for these parameters are presented in

Table 1.

The parameters in Group 2 are derived by targeting four key steady-state values. Firstly, real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is defined as the sum of current real final output (

) and current real investment in housing (

). Subsequently, the steady-state values for four key variables are determined. The first variable, denoted as

, represents the proportion of public investment in real GDP. The steady-state value of this variable is 14.5%, according to Chang et al. (2019) [

42]. This value corresponds to the sample average of public investment as a share of GDP in China over 2001–2019. The second variable,

, represents the housing investment-to-GDP ratio in the steady state. We set this proportion to 14%. This value follows Mei et al. (2018) [

43], who estimate that real estate investment accounted for roughly 14% of China’s GDP over 2008–2018. The third variable denotes the steady-state labor supply of patient households, and the fourth that of impatient households. Following Devereux and Yu (2019) [

41], the household labor supply is set to 1. Finally, based on the given steady-state values, the model derives four structural parameters related to them. Both target values are obtained under a normalized labor-supply specification.

These parameters include

, representing the steady-state value of housing demand shocks;

, representing the steady-state value of the weight on patient household labor supply;

, representing the steady-state tax rate levied by local governments on corporate income; and

, representing the steady-state weight on impatient household labor supply. Specific numerical values are provided in

Table 2.

Using Bayesian estimation, this paper estimates the parameter range for Group 3. Group 3 includes the following parameters

. The parameters in Group 3 are estimated using quarterly macroeconomic data—real housing prices and GDP per capita—over the sample period 2005 Q1–2017 Q4. Prior to estimation, the series are detrended using the HP filter to extract their cyclical components. Bayesian estimates are reported in

Table 3. The prior distributions largely follow conventions in the DSGE literature. They are anchored to Iacoviello and Neri (2010) [

35] and Smets and Wouters (2007) [

44], which ensures comparability with existing studies and provides economically meaningful identification.

Table 4 reports the variance decompositions for key macroeconomic variables. Housing-demand shocks account for a large and persistent share of the fluctuations in housing prices, residential land prices, firm credit, and local public investment. In all four cases, their contribution exceeds 70 percent, indicating that shocks to housing-demand preferences constitute the dominant source of aggregate fluctuations in this economy. Motivated by this empirical relevance, the subsequent analysis concentrates on the propagation and macroeconomic implications of housing-demand shocks.

6. Welfare Gains and Volatility Measurement

This section compares the volatility of key macroeconomic variables under two inflation-targeting regimes. It also measures welfare using a consumption-equivalent metric. The welfare calculation follows the approach of Devereux and Yu (2019) [

41]. The method applies to three representative agents: patient households, impatient households, and entrepreneurs.

The policy experiments measure welfare through a consumption-equivalent welfare gain. We take the “no-circuit-breaker baseline” as the reference scenario. For each agent

, we define the welfare gain

. The gain

equals the consumption reduction that makes the agent’s lifetime utility in the circuit-breaker regime match the baseline. Formally,

indicates a welfare improvement for agent

. Conversely,

indicates a welfare loss. The index

denotes patient households,

denotes impatient households, and

denotes entrepreneurs.

In Equation (33),

denotes lifetime utility for agent

under the circuit-breaker regime. Similarly,

denotes lifetime utility for agent

under the benchmark regime. Lifetime utility for agent

under policy regime

is

Since the three agents have equal population weights, the aggregate welfare gain is

This weighting scheme follows Devereux and Yu (2019) [

41].

From an economic perspective, welfare gains arise through two channels. (i) Extensive margin: credit reallocation across sectors. The circuit breaker improves welfare primarily by reallocating credit from housing activities toward productive firms. Strict inflation targeting restrains the growth of land and house prices, slowing collateral appreciation for impatient households and limiting their borrowing capacity. Because patient households supply the aggregate credit pool, weaker mortgage demand increases the share of credit flowing to firms. This shift mitigates the decline in investment and supports the accumulation of private capital. Since private capital has higher marginal returns, this shift generates first-order gains in firm output and efficiency. (ii) Intensive margin: stabilization of land and housing prices. The circuit breaker also stabilizes land and house price fluctuations, improving wealth and consumption stability. By capping land price surges, it moderates developers’ costs, land demand, and the flow of new housing supply. This channel yields two stabilizing effects. First, lower housing wealth volatility smooths consumption paths and raises household utility, because housing services enter utility directly. Second, reduced collateral volatility dampens the amplitude of credit cycles. With milder house price movements, collateralized borrowing becomes more stable, reducing the procyclicality of credit. These stabilization effects form the second major source of welfare gains.

The first column in

Table 5 shows the volatilities of

(housing prices),

(residential land prices),

(inflation),

(impatient households’ loans),

(firms’ loans),

(productive investment by firms),

(public investment by local governments), and

(final output of firms).

Key macroeconomic variables display substantially lower volatility under a strict inflation target, as indicated by the variance comparison in

Table 5. This outcome suggests that the occasional activation of the land price circuit breaker effectively dampens fluctuations across the system. Under strict inflation targeting, the circuit breaker significantly raises overall welfare. The mechanism curbs rapid increases in housing prices, allowing a larger share of credit to shift from household mortgages toward firms. This reallocation stimulates firm output and, in turn, supports higher aggregate consumption. Consequently, overall social welfare increases markedly.

7. Conclusions

This study develops a multi-sector DSGE model featuring a land price circuit breaker. The model analyzes its trigger conditions, transmission channels, and macroeconomic effects under alternative inflation-targeting regimes. The findings show that the circuit breaker is not a static price cap. Instead, it functions as a threshold-based, state-dependent regulatory tool with endogenous activation. Its logic aligns closely with the framework of occasionally binding constraints. The mechanism switches policy states in response to housing demand shocks, making price regulation more flexible and institutionally realistic.

Strict inflation targeting significantly raises the probability of triggering the circuit breaker. When nominal adjustment space is compressed, housing demand shocks concentrate more on land prices, making it easier to hit the policy ceiling. This finding reveals an institutional link between nominal monetary anchoring and dynamic land price regulation. Activation of the circuit breaker markedly slows the growth of land and housing prices, weakening the procyclicality of collateral values and reducing impatient households’ credit expansion. This process generates cross-sector credit reallocation: firms face less financing squeeze, fewer investment contracts, private capital accumulation accelerates, and aggregate output recovers more rapidly. The circuit breaker also restricts land supply and diverts part of the demand to the secondary housing market, producing a “release stock—stabilize prices” effect on housing supply. These dynamics help dampen fluctuations in the real estate sector and enhance stability across connected markets.

From an economic perspective, the results highlight the role of the land price circuit breaker as a tool for sustainable land-use policy. The mechanism functions not only as a price control in land auctions but also generates complex interactions across credit, housing, and fiscal channels. When combined with strict inflation targeting, it creates policy complementarity: monetary policy provides nominal constraints, while land policy imposes relative price discipline. Together, they build a more robust transmission chain linking the real estate, financial, and real sectors, thereby strengthening the sustainability of economic growth.

This study offers a systematic theoretical framework but still faces several limitations. First, the model does not incorporate local government heterogeneity. Such heterogeneity includes differences in land tax reliance, population inflows, and real estate cycles across cities, which may shape the spatial distribution of trigger probabilities and policy effects. Second, housing-demand shocks are the main drivers in the model. However, real estate fluctuations in practice arise from multiple interacting forces, including shifts in expectations, financial regulation, and urbanization dynamics. Third, the land price band is modeled as a simplified weighted average of past prices. Actual policies are more complex and may involve zoning rules, quality-based bidding, or requirements for subsidized housing.

Future research can proceed along three directions. First, incorporating regional heterogeneity or a multi-city structure would allow analysis of cross-city differences in circuit breaker activation. Such a framework would also clarify the mechanism’s cross-regional effects on national housing-market stability. Second, the model could incorporate richer financial frictions, such as expectation formation, bank capital constraints, and shadow banking dynamics. These additions would better capture the amplifying role of real estate financialization in macroeconomic fluctuations. Third, combining the theoretical model with actual land auction data would enable event studies or structural estimation. Such empirical work could evaluate the circuit breaker’s real-world trigger frequency, price-suppression effects, and welfare implications, thereby strengthening the integration of theory and evidence.

Overall, this study uncovers the endogenous trigger mechanism and cross-market transmission channels of the land price circuit breaker under strict inflation targeting. It shows that the mechanism can curb real estate procyclicality, improve credit allocation, and stabilize the macroeconomy. These findings highlight its potential as a tool for sustainable land-use policy and provide new theoretical and policy insights for designing a more robust macro-regulatory framework.

_Li.png)