Analysis of Industrial Flue Gas Compositions and Their Impact on Molten Carbonate Fuel Cell Performance for CO2 Separation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. MCFC as a CO2 Separator in the Power Engineering Industry

1.2. Novelty of the Paper

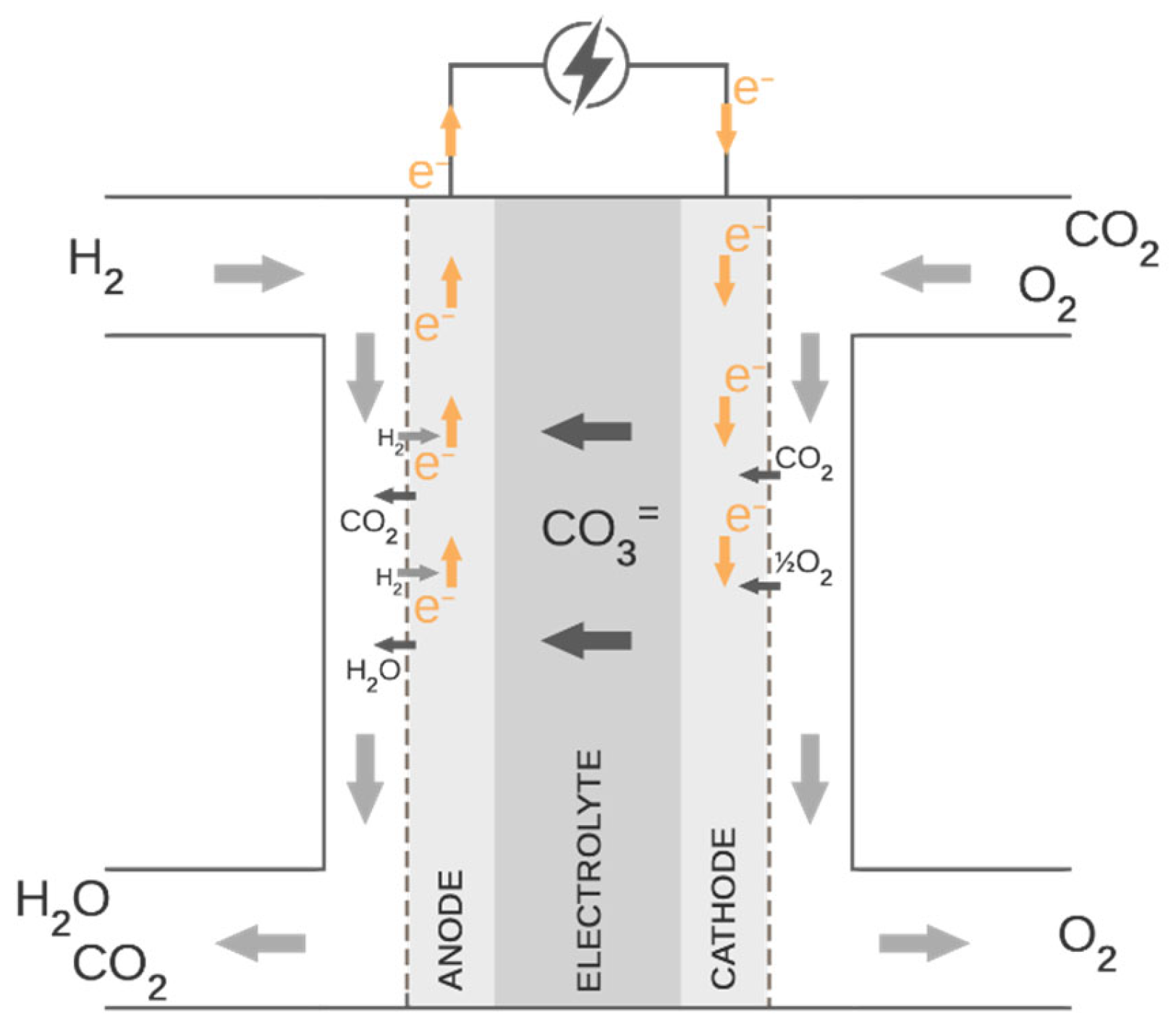

2. Theoretical Background of Molten Carbonate Fuel Cell Operation

3. Overview of Industrial Flue Gas Sources for CCS Application

3.1. Gas Turbine Power Plants

3.2. Hard Coal Power Plants

3.3. Lignite Power Plants

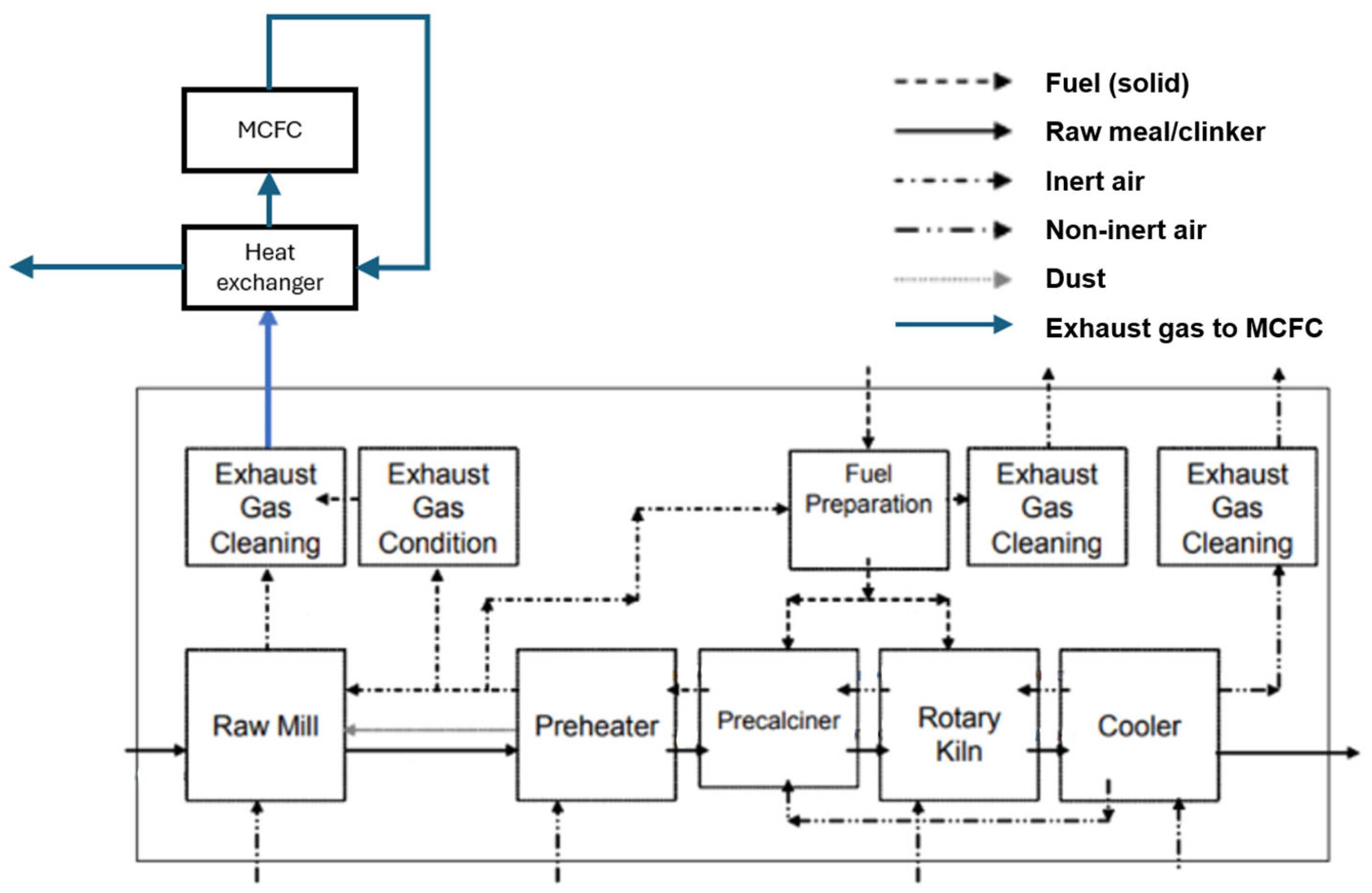

3.4. Cement Industry

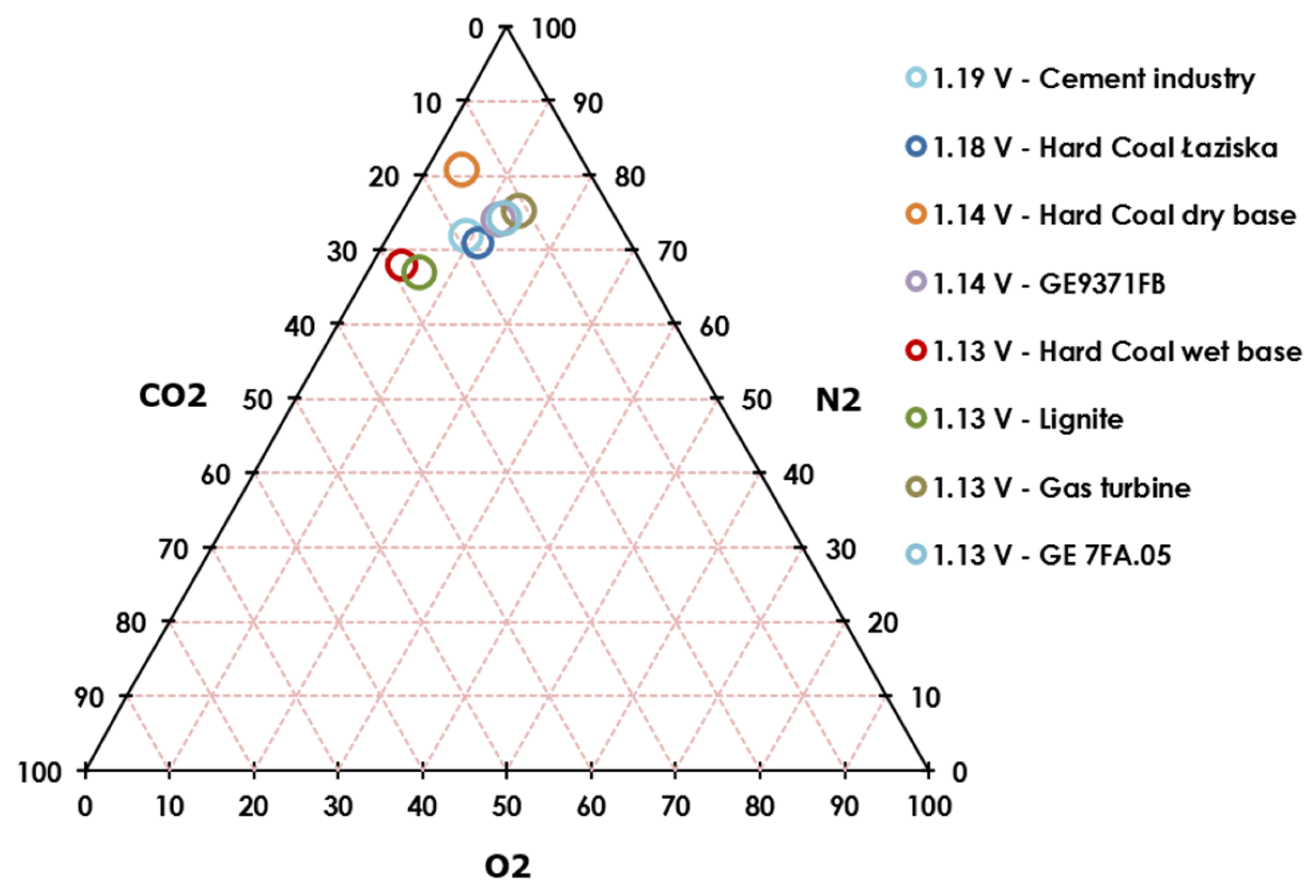

4. Discussion of Selected Flue Gas Intake Points and MCFC Suitability

4.1. Gas Turbine Power Plants

4.2. Hard Coal Power Plants

4.3. Lignite Power Plants

4.4. Cement Industry

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Symbol/Formula | Description |

| γ | Gamma phase in crystal structures (e.g., γ-LiAlO2 matrix for fuel cells) |

| LiAlO2 | Lithium aluminate (gamma phase used in MCFC matrices) |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide (e.g., in CO2 separation membranes) |

| H2 | Hydrogen (e.g., in H2 production via electrolysis) |

| CeO2 | Cerium dioxide (base for samaria-doped ceria in fuel cells) |

| Sm2O3 | Samarium oxide (dopant in samaria-doped ceria) |

| Li/K | Lithium/potassium electrolyte (in MCFC) |

References

- Dhamu, V.; Qureshi, M.F.; Selvaraj, N.; Yuanmin, L.J.; Guo, I.T.; Linga, P. Dual Promotional Effect of l-Tryptophan and 1,3-Dioxane on CO2 Hydrate Kinetics in Seawater Under Static/Unstatic Conditions for Carbon Capture and Storage Application. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 11980–11993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhamu, V.; Mengqi, X.; Qureshi, M.F.; Yin, Z.; Jana, A.K.; Linga, P. Evaluating CO2 hydrate kinetics in multi-layered sediments using experimental and machine learning approach: Applicable to CO2 sequestration. Energy 2024, 290, 129947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminnaji, M.; Qureshi, M.F.; Dashti, H.; Hase, A.; Mosalanejad, A.; Jahanbakhsh, A.; Babaei, M.; Amiri, A.; Maroto-Valer, M. CO2 Gas hydrate for carbon capture and storage applications—Part 1. Energy 2024, 300, 131579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminnaji, M.; Qureshi, M.F.; Dashti, H.; Hase, A.; Mosalanejad, A.; Jahanbakhsh, A.; Babaei, M.; Amiri, A.; Maroto-Valer, M. CO2 gas hydrate for carbon capture and storage applications—Part 2. Energy 2024, 300, 131580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhamu, V.; Qureshi, M.F.; Barckholtz, T.A.; Mhadeshwar, A.B.; Linga, P. Evaluating liquid CO2 hydrate formation kinetics, morphology, and stability in oceanic sediments on a lab scale using top injection. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 478, 147200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeenmuang, K.; Pornaroontham, P.; Fahed Qureshi, M.; Linga, P.; Rangsunvigit, P. Micro kinetic analysis of the CO2 hydrate formation and dissociation with L-tryptophan in brine via high pressure in situ Raman spectroscopy for CO2 sequestration. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 479, 147691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhamu, V.; Qureshi, M.F.; Abubakar, S.; Usadi, A.; Barckholtz, T.A.; Mhadeshwar, A.B.; Linga, P. Investigating High-Pressure Liquid CO2 Hydrate Formation, Dissociation Kinetics, and Morphology in Brine and Freshwater Static Systems. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 8406–8420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M.F.; Khandelwal, H.; Usadi, A.; Barckholtz, T.A.; Mhadeshwar, A.B.; Linga, P. CO2 hydrate stability in oceanic sediments under brine conditions. Energy 2022, 256, 124625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahed Qureshi, M.; Zheng, J.; Khandelwal, H.; Venkataraman, P.; Usadi, A.; Barckholtz, T.A.; Mhadeshwar, A.B.; Linga, P. Laboratory demonstration of the stability of CO2 hydrates in deep-oceanic sediments. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 432, 134290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanari, S. Carbon dioxide separation from high temperature fuel cell power plants. J. Power Sources 2002, 112, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanari, S.; Chiesa, P.; Manzolini, G. CO2 capture from combined cycles integrated with Molten Carbonate Fuel Cells. Int. J. Greenh. Gas. Control 2010, 4, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorelli, A.; Wilkinson, M.B.; Bedont, P.; Capobianco, P.; Marcenaro, B.; Parodi, F.; Torazza, A. An experimental investigation into the use of molten carbonate fuel cells to capture CO2 from gas turbine exhaust gases. Energy 2004, 29, 1279–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, M.; Bosio, B.; Arato, E. An example of innovative application in fuel cell system development: CO2 segregation using Molten Carbonate Fuel Cells. J. Power Sources 2004, 131, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, K.; Takei, K.; Tanimoto, K.; Miyazaki, Y. The carbon dioxide concentrator by using MCFC. J. Power Sources 2003, 118, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, J.H. Contribution of fuel cell systems to CO2 emission reduction in their application fields. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastropasqua, L.; Spinelli, M.; Paganoni, A.; Campanari, S. Preliminary design of a MW-class demo system for CO2 capture with MCFC in a university campus cogeneration plant. Energy Procedia 2017, 126, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carapellucci, R.; Di Battista, D.; Cipollone, R. The retrofitting of a coal-fired subcritical steam power plant for carbon dioxide capture: A comparison between MCFC-based active systems and conventional MEA. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 194, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastropasqua, L.; Pierangelo, L.; Spinelli, M.; Romano, M.C.; Campanari, S.; Consonni, S. Molten Carbonate Fuel Cells retrofits for CO2 capture and enhanced energy production in the steel industry. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2019, 88, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dybiński, O.; Milewski, J.; Szabłowski, Ł.; Szczęśniak, A.; Martinchyk, A. Methanol, ethanol, propanol, butanol and glycerol as hydrogen carriers for direct utilization in molten carbonate fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 37637–37653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milewski, J.; Bujalski, W.; Wołowicz, M.; Futyma, K.; Kucowski, J.; Bernat, R. Experimental Investigation of CO2 Separation from Hard Coal Flue Gases by 100 cm2 Molten Carbonate Fuel Cell. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 302, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Martsinchyk, A.; Gaukas, N.; Milewski, J.; Shuhayeu, P.; Denonville, C.; Szczesniak, A.; Sieńko, A.; Dybiński, O. Exploring new solid electrolyte support matrix materials for molten carbonate fuel cells (MCFCs). Fuel 2024, 371, 132144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuhayeu, P.; Martsinchyk, A.; Martsinchyk, K.; Szczęśniak, A.; Szabłowski, Ł.; Dybiński, O.; Milewski, J. Model-based quantitative characterization of anode microstructure and its effect on the performance of molten carbonate fuel cell. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 902–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milewski, J.; Lewandowski, J.; Miller, A. Reducing CO2 Emission from Fossil Power Plants by Using a Molten Carbonate Fuel Cell. In Proceedings of the 17th World Hydrogen Energy Conference, Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 15–19 June 2008; p. 132. [Google Scholar]

- Milewski, J.; Lewandowski, J.; Miller, A. Reducing CO2 emissions from a coal fired power plant by using a molten carbonate fuel cell. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2008: Power for Land, Sea, and Air, Berlin, Germany, 9–13 June 2008; Volume 2, pp. 389–395. [Google Scholar]

- Palomino, L. Selective Exhaust Gas Recirculation in Combined Cycle Gas Turbine Power Plants with Post-Combustion Carbon Capture. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Herraiz, L.; Sanchez Fernandez, E.; Gibbins, J.; Lucquiaud, M. Selective Exhaust Gas Recirculation in Combined Cycle Gas Turbine Power Plants with Post-combustion Carbon Capture. In Proceedings of the 8th Trondheim Conference on CO2 Capture, Transport and Storage, Trondheim, Norway, 16–18 June 2015; pp. 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Roointon, P.; Moore, G. Gas turbine emissions and control, GER-4211 2001. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/GER-4211-Gas-Turbine-Emissions-and-Control-Pavri-Moore/fbb6b51a47e9d12a0adfcaaf4194f45d431d9c63 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Wiecław-Solny, L.; Tatarczuk, A.; Stec, M.; Krótki, A. Advanced CO2 capture pilot plant at tauron’s coal-fired power plant: Initial results and further opportunities. Energy Procedia 2014, 63, 6318–6322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krótki, A.; Więcław Solny, L.; Stec, M.; Spietz, T.; Wilk, A.; Chwoła, T.; Jastrząb, K. Experimental results of advanced technological modifications for a CO2 capture process using amine scrubbing. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2020, 96, 103014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DOE/NETL-2010/1397; DOE. Cost and Performance Baseline for Fossil Energy Plants Volume 1: Bituminous Coal and Natural Gas to Electricity. National Energy Technology Laboratory: Pittsburgh, PA, USA; Morgantown, WV, USA; Albany, OR, USA, 2013; Volume 1.

- Adu, E.; Zhang, Y.D.; Liu, D.; Tontiwachwuthikul, P. Parametric process design and economic analysis of post-combustion CO2 capture and compression for coal- and natural gas-fired power plants. Energies 2020, 13, 2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Arvid Lie, J.; Sheridan, E.; Hägg, M.B. CO2 capture by hollow fibre carbon membranes: Experiments and process simulations. Energy Procedia 2009, 1, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milewski, J.; Bujalski, W.; Wołowicz, M.; Futyma, K.; Kucowski, J.; Bernat, R. Experimental investigation of CO2 separation from lignite flue gases by 100 cm2 single Molten Carbonate Fuel Cell. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 1558–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.B.; Saidur, R.; Hossain, M.S. A review on emission analysis in cement industries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 2252–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosoaga, A.; Masek, O.; Oakey, J.E. CO2 Capture Technologies for Cement Industry. Energy Procedia 2009, 1, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elena Diego, M.; Bellas, J.M.; Pourkashanian, M. Process Analysis of Selective Exhaust Gas Recirculation for CO2 Capture in Natural Gas Combined Cycle Power Plants Using Amines. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2017, 139, 121701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyrkowski, M.; Motak, M. Formation of ammonia bisulfate in coal-fired power plant equipped with SCR reactors and the effect of reduced load operation. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 137, 01021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, S.A.; Laumb, J.D.; Crocker, C.R.; Pavlish, J.H. SCR catalyst performance in flue gases derived from subbituminous and lignite coals. Fuel Process Technol. 2005, 86, 577–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergaršek, A.; Horvat, M.; Kotnik, J.; Tratnik, J.; Frkal, P.; Kocman, D.; Jaćimović, R.; Fajon, V.; Ponikvar, M.; Hrastel, I.; et al. The role of flue gas desulphurisation in mercury speciation and distribution in a lignite burning power plant. Fuel 2008, 87, 3504–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczak, M.; Wierońska, F.; Burmistrz, P.; Strugała, A.; Kogut, K.; Lech, S. Investigation of subbituminous coal and lignite combustion processes in terms of mercury and arsenic removal. Fuel 2019, 251, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, N.; Moya, J.A.; Mercier, A. Prospective on the energy efficiency and CO2 emissions in the EU cement industry. Energy 2011, 36, 3244–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, D. Chairman of the advisory board: European Cement Research Academy ECRA CCS Project-Report About Phase II. Available online: https://api.ecra-online.org/fileadmin/files/ECRA__Technical_Report_CCS_Phase_II.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Barker, D.J.; Turner, S.A.; Napier-Moore, P.A.; Clark, M.; Davison, J.E. CO2 Capture in the Cement Industry. Energy Procedia 2009, 1, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desideri, U.; Proietti, S.; Sdringola, P.; Cinti, G.; Curbis, F. MCFC-based CO2 capture system for small scale CHP plants. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 19295–19303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Components | Flue Gas Composition | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas Turbine Unit | Coal-Fired Unit | Cement Industry | ||||||||||

| [23,24] | [25] | [26] | [27] | [28] | [29] | [30,31] | [32] | [32] | [33] | [34] | [35] | |

| CO2, %vol | 5.44 | 4.21 | 3.9 | 1–5 | 13.05 | 13.2 | 13.5 | 12.5 | 15 | 10–14 | 12 | 14–33 |

| H2O, %vol | 3.58 | 8.82 | 8.4 | 5.05 | 5.05 | 7.3 | 15.37 | 16 | 0 | 16–20 | 15 | n/a |

| O2, %vol | 11.48 | 11.9 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 8.7 | 2.38 | 3.5 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8–14 |

| N2, %vol | 78.62 | 74.2 | 74 | 66–72 | n/a | n/a | 71.62 | 68 | 81 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Ar, %vol | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.9 | n/a | n/a | n/a | 0.68 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| NO, ppmv | n/a | n/a | n/a | 20–220 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 120 | n/a |

| NO2, ppmv | n/a | n/a | n/a | 2–20 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 0.1 | 6 | 10–110 |

| NOx, mg/m3 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 200–300 | 200–400 | n/a | 68 | 81 | n/a | n/a | <300–3000 |

| CO, ppmv | n/a | n/a | n/a | 5–330 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| SO2, ppmv | n/a | n/a | n/a | Trace–100 | 100–200 | 100–200 | 0 | n/a | n/a | <2600 | 580 | <10–3500 |

| SO3, ppmv | n/a | n/a | n/a | Trace–4 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 40 | n/a | n/a |

| HCl, ppm | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 300 | 1 | n/a |

| HF, ppm | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 45 | n/a | n/a |

| Unburned Hydrocarbon, ppmy | n/a | n/a | n/a | 5–300 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Particulate Matter Smoke, ppmv | n/a | n/a | n/a | Trace–25 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Ash/Dust, mg/m3 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 100 | 30 | n/a | n/a | n/a | 50 | n/a | n/a |

| Name | Value |

|---|---|

| Air compressor inlet pressure, MPa | 0.1 |

| Air compressor inlet temperature, °C | 15 |

| Pressure ratio | 17.1 |

| Fuel | Natural gas |

| Fuel mass flow, kg/s | 4.0 |

| Turbine inlet temperature, °C | 1210 |

| Exhaust gas mass flow, kg/s | 213 |

| Turbine outlet temperature, °C | 587 |

| GT power, MW | 65 |

| GT efficiency (LHV), % | 33 |

| CO2 annual emission, Gg/a | 250 |

| Relative emission of CO2, kg/MWh | 609 |

| CO2 mass flow, kg/s | 11 |

| Name | Value |

|---|---|

| Air mass flow rate, kg/s | 641.81 |

| Fuel mass flow rate, kg/s | 16.10 |

| Pressure ratio | 18.1 |

| Fuel | Natural gas |

| Turbine inlet temperature, °C | 1371 |

| Exhaust temperature, °C | 643.29 |

| Exhaust gas mass flow, kg/s | 657.92 |

| Net power, MW | 285.76 |

| Net thermal efficiency, % | 38.18 |

| Name | Value |

|---|---|

| Air inlet temperature, °C | 15 |

| Fuel inlet temperature, °C | 38 |

| GT power output, Mwe | 418.7 |

| Compressor pressure ration | 17 |

| Turbine inlet temperature | 1360 |

| Air composition, %vol | |

| N2 | 77.32 |

| O2 | 20.74 |

| Ar | 0.92 |

| CO2 | 0.03 |

| H2O | 0.99 |

| Component | Antelope | Caballo | Beulah |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ash | 7.28 | 6.59 | 11.62 |

| S | 0.33 | 0.51 | 1.49 |

| C | 69.97 | 67.88 | 61.50 |

| H | 4.77 | 4.83 | 3.96 |

| N | 1.05 | 1.24 | 1.08 |

| O | 16.61 | 18.96 | |

| Ash | 7.28 | 6.59 | 11.62 |

| S | 0.33 | 0.51 | 1.49 |

| Ereference | E(O2 + 10%) (ΔE, %) | E(O2–10%) (ΔE, %) | E(CO2−10%) (ΔE, %) | E(CO2−10%) (ΔE, %) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas turbine | 1.1359 V | 1.1339 V (−0.18%) | 1.1377 V (+0.16%) | 1.1164 V (−1.72%) | 1.1487 V (+1.13%) |

| Gas turbine GE 7FA.05 | 1.1411 V | 1.1391 V (−0.17%) | 1.1429 V (+0.16%) | 1.1285 V (−1.11%) | 1.1506 V (+0.83%) |

| Hard Coal Łaziska | 1.1818 V | 1.1798 V (−0.17%) | 1.1836 V (+0.15%) | 1.1784 V (−0.29%) | 1.1849 V (+0.26%) |

| Lignite | 1.1354 V | 1.1291 V (−0.55%) | 1.1413 V (+0.52%) | 1.1343 V (−0.10%) | 1.1365 V (+0.09%) |

| Cement industry | 1.1909 V | 1.1847 V (−0.52%) | 1.1928 V (+0.16%) | 1.1889 V (−0.17%) | 1.1928 V (+0.16%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szczęśniak, A.; Martsinchyk, A.; Dybinski, O.; Martsinchyk, K.; Milewski, J.; Szabłowski, Ł.; Brouwer, J. Analysis of Industrial Flue Gas Compositions and Their Impact on Molten Carbonate Fuel Cell Performance for CO2 Separation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11234. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411234

Szczęśniak A, Martsinchyk A, Dybinski O, Martsinchyk K, Milewski J, Szabłowski Ł, Brouwer J. Analysis of Industrial Flue Gas Compositions and Their Impact on Molten Carbonate Fuel Cell Performance for CO2 Separation. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11234. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411234

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzczęśniak, Arkadiusz, Aliaksandr Martsinchyk, Olaf Dybinski, Katsiaryna Martsinchyk, Jarosław Milewski, Łukasz Szabłowski, and Jacob Brouwer. 2025. "Analysis of Industrial Flue Gas Compositions and Their Impact on Molten Carbonate Fuel Cell Performance for CO2 Separation" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11234. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411234

APA StyleSzczęśniak, A., Martsinchyk, A., Dybinski, O., Martsinchyk, K., Milewski, J., Szabłowski, Ł., & Brouwer, J. (2025). Analysis of Industrial Flue Gas Compositions and Their Impact on Molten Carbonate Fuel Cell Performance for CO2 Separation. Sustainability, 17(24), 11234. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411234