1. Introduction

Rapid technological transformations and sustainability challenges are reshaping expectations toward engineering education, which must now prepare students to act as innovators capable of translating advanced knowledge into societal impact [

1]. Engineers are expected to demonstrate not only technical excellence but also entrepreneurial mindsets, creativity, adaptability, leadership, and strategic thinking to identify and transform opportunities into sustainable deep-tech ventures [

2,

3]. Within this context, technopreneurship, the combination of technology and entrepreneurship aimed at creating and growing innovation-driven ventures, has become increasingly important. It involves identifying opportunities emerging from technological advancements, developing innovative technology-based products or services, and designing viable business models to commercialize them responsibly. Unlike traditional entrepreneurship, it emphasizes advanced technologies and carries a higher potential for disruption and growth.

However, technopreneurship education remains fragmented and underdeveloped in most engineering programs. Studies indicate that such courses are often delivered as isolated workshops or electives, lacking structured pathways that support progressive competency development [

4,

5,

6]. Consequently, many students graduate without sufficient preparation to operate in innovation-driven environments characterized by uncertainty and sustainability constraints [

7,

8]. Technopreneurship, the intersection of technological innovation and entrepreneurship, is increasingly acknowledged as central to competitiveness, job creation, and green and digital transitions [

9,

10]. Research further shows that its inclusion in higher education enhances students’ confidence, motivation, innovation capacity, and career readiness in technology-intensive domains [

11,

12,

13]. Yet several systemic challenges persist: limited infrastructure, weak university–industry collaboration, limited access to expert mentors, and outdated teaching methods that fail to reflect real innovation ecosystems [

14,

15,

16]. These gaps are particularly evident in deep-tech contexts, where long development cycles, high risks, and interdisciplinary collaboration are essential for success [

3,

17].

At the policy level, global policy frameworks emphasize the role of engineering education in advancing sustainability. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG-4) calls for high-quality, inclusive education that equips learners with competencies for sustainable industrial development and innovation. Technopreneurship directly aligns with these aims by fostering solution-driven thinking, market awareness, stakeholder engagement, and responsible innovation practices [

18].

To advance technopreneurship education in engineering, research increasingly focuses on pedagogical models that encourage collaboration, creativity, and real-world problem-solving. Within this context, four approaches commonly emerge as relevant in the literature: Project-Based Learning (PBL), Technology-Enhanced Learning (TEL), Jigsaw collaborative learning, and international or interdisciplinary teamwork [

19,

20,

21,

22]. However, existing studies typically examine these frameworks independently, without exploring how they can be combined to support sustainable venture development. Consequently, the literature leaves open the question of how these approaches could be integrated into a coherent, multi-stage learning strategy for deep-tech entrepreneurship competencies [

23,

24,

25].

Based on these gaps, this review is guided by the following research questions:

What educational contributions and limitations are reported in the literature regarding the four pedagogical approaches most often discussed in technopreneurship-oriented engineering education (PBL, TEL, Jigsaw, and international/interdisciplinary teamwork)? (RQ1)

How do these pedagogical approaches support (or fail to support) the development of key competencies required for sustainable technopreneurship in engineering eduction? (RQ2)

To what extent does current literature integrate sustainability, entrepreneurship, and collaboration within technopreneurship-oriented pedagogical models? (RQ3)

What conceptual gaps in existing pedagogical models indicate the need for an integrated framework such as the proposed Innovation and Technopreneurship Education Model? (RQ4)

In line with these research questions, the present review aims to:

- −

synthesize state-of-the-art research on pedagogical approaches supporting technopreneurship in engineering education,

- −

identify key research and practice gaps limiting sustainable competency development,

- −

establish the conceptual rationale for an integrated instructional framework aligned with sustainability goals.

The manuscript is structured as follows.

Section 2 presents the methodology guiding the literature identification, coding, and synthesis processes.

Section 3 outlines the key contextual challenges and systemic gaps shaping technopreneurship education in engineering.

Section 4 examines the four pedagogical frameworks that underpin the review: PBL, TEL, Jigsaw collaborative learning, and international or interdisciplinary teamwork, and presents a structured synthesis of their methodological characteristics and reported learning outcomes.

Section 5 maps these approaches onto four core competency domains essential for sustainable technopreneurship.

Section 6 integrates the findings to identify cross-cutting research gaps.

Section 7 develops the conceptual foundation of the Innovation and Technopreneurship Education Model (ITEM) based on the reviewed evidence. Finally,

Section 8 concludes the study and outlines directions for future research.

This study forms the first stage of a broader research program on the ITEM, a sustainability-oriented framework designed to integrate key pedagogical strategies into a coherent learning pathway for future engineers that can be implemented in their curricula. The program comprises three stages:

- (1)

Establishing its theoretical foundations;

- (2)

Designing and piloting the integrated model;

- (3)

Conducting empirical evaluation of learning outcomes.

2. Methodology

This study adopts a structured narrative review approach designed to synthesize research on technopreneurship education in engineering and identify integrative pedagogical pathways for sustainable competency development. The review focused on peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, and conceptual studies published between 2018 and 2025. The time scope was deliberately selected to capture the most recent period of intensified global focus on sustainability-oriented engineering and entrepreneurship education, beginning with the 2018 SDG acceleration phase in which SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure) underwent formal review cycles that renewed emphasis on sustainability competencies.

Relevant publications were retrieved from Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases using combinations of the following keywords: technopreneurship education, engineering entrepreneurship, sustainability, deep-tech ventures, Project-Based Learning, Technology-Enhanced Learning, Jigsaw collaborative learning, international collaboration, and interdisciplinary teamwork. The search identified approximately 27 publications in Scopus, 13 in Web of Science, and 48 in Google Scholar (including duplicates). After applying the inclusion criteria, 29 studies were retained for full-text analysis. Sources were included if they addressed (1) pedagogical design or delivery in higher-education engineering programs, (2) learning outcomes linked to innovation, entrepreneurship, or sustainability, and (3) conceptual or empirical insights into competency development. Studies not addressing at least one of the four pedagogical frameworks or not focused on engineering education were excluded.

To reflect the analytical scope of the article, the methodology combines a review component with a synthesis component. The review component involved title and abstract screening of all retrieved publications, followed by full-text assessment to confirm eligibility. Each included study was then classified according to its dominant pedagogical framework: PBL, TEL, Jigsaw collaborative learning, or international/interdisciplinary teamwork. The synthesis component began with coding the reported learning outcomes of each publication. These outcomes were mapped to four competency domains identified as essential for sustainable technopreneurship in engineering education: (1) innovation and creativity, (2) sustainability and impact orientation, (3) entrepreneurial and strategic skills, and (4) collaboration and global awareness. This was followed by a partial quantification of patterns across the literature, including the distribution of study types across frameworks and the frequency of reported outcomes. These quantitative insights provide a transparent basis for comparing the relative contributions of each pedagogical approach.

The final stage of the methodology consisted of an integrative interpretation that synthesized patterns and gaps in the evidence base. This cross-framework analysis identified complementary strengths and underrepresented areas related to sustainability, entrepreneurship, and collaboration, thereby forming the conceptual foundation for the development of the ITEM.

Figure 1 summarizes the methodological workflow of the study, illustrating how the literature search, screening, framework classification, outcome coding, quantitative consolidation, and integrative synthesis jointly support the analytical structure of the article.

The steps outlined above provide the analytical foundation for the subsequent sections by structuring how the evidence is organized, interpreted, and synthesized. The classification, coding, and quantitative patterning inform the analysis of pedagogical frameworks and competency domains, while the integrative synthesis supports the identification of gaps and the conceptual development of the item model.

3. Challenges in Technopreneurship Education

Although Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) increasingly recognize the importance of developing entrepreneurial capability among engineers, technopreneurship education still faces persistent pedagogical, structural, and ecosystem-related challenges. The literature highlights fragmented learning experiences, weak connections to authentic innovation contexts, and limited attention to sustainability and global collaboration. The following sub-sections outline the main pedagogical and structural barriers that currently limit the effectiveness of technopreneurship education in engineering programs offered by HEIs. They address fragmented competence development, limited real-world relevance, insufficient integration of sustainability, reliance on traditional teaching methods, weak interdisciplinary and global exposure, and poor alignment with innovation ecosystems. Together, these factors illustrate the systemic obstacles that must be overcome to enable sustainable technopreneurial learning in engineering education.

3.1. Fragmented and Nonlinear Competence Development

Many engineering programs introduce entrepreneurship through disconnected short courses, workshops, or hackathons, offering few opportunities for progressive skill development [

4,

5]. These formats often lack alignment with engineering learning trajectories and provide insufficient exposure to the realities of venture creation [

6]. As a result, students may understand business concepts theoretically but struggle to apply their technical expertise within viable innovation processes [

11].

3.2. Limited Real-World Relevance and Venture Realism

A recurring issue is the gap between classroom exercises and actual innovation ecosystems [

1]. Activities often emphasize business-plan writing instead of prototyping, customer discovery, and feasibility validation, which are essential to deep-tech ventures [

13]. Without industry mentorship and multidisciplinary collaboration, students rarely experience the complexity of opportunity shaping needed for sustainable competitiveness [

2,

3].

3.3. Insufficient Integration of Sustainability

While sustainability is a declared priority in engineering education, entrepreneurship courses often focus on commercial viability alone, overlooking environmental and social impact [

18]. This omission limits students’ capacity for responsible innovation aligned with SDG-4 (Quality Education) and SDG-9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructures) and weakens their ability to design ventures that contribute to green and digital transitions, circularity, or social inclusion.

3.4. Traditional Teaching Practices

Traditional lecture-centered instruction still dominates in some contexts, constraining engagement and creativity [

16]. Such approaches conflict with innovation learning, which requires exploration, iteration, teamwork, and problem framing in ambiguous environments [

7]. Consequently, students may excel technically yet lack entrepreneurial confidence, interdisciplinary communication, and the ability to articulate sustainable value propositions [

12].

3.5. Limited Interdisciplinary and Global Exposure

Deep-tech ventures typically integrate multiple domains like materials science, electronics, design, and business, but many programs remain siloed and provide little cross-disciplinary interaction [

17]. Similarly, limited international collaboration reduces students’ awareness of global markets, regulatory diversity, and intercultural teamwork [

15].

3.6. Weak Alignment with Innovation Ecosystems

Insufficient collaboration between HEIs and industry is consistently identified as a structural barrier [

14]. Limited access to practitioners, fabrication labs, accelerators, and intellectual property or legal support undermines venture realism and restricts students’ exposure to authentic development cycles [

22]. When technopreneurship is taught in isolation from such ecosystems, students rarely reach technology-readiness levels that justify venture creation or scaling [

10].

3.7. Towards Synthesizing Challenges and Implications for Pedagogical Design

The challenges outlined above reveal interrelated gaps that collectively constrain the effectiveness of technopreneurship education in engineering programs offered by HEIs. Fragmented learning experiences prevent students from developing competencies progressively, while limited exposure to real innovation ecosystems and weak integration of sustainability restrict the authenticity and long-term impact of learning. Traditional teaching methods, together with insufficient interdisciplinary and international collaboration, reduce students’ readiness to address complex, sustainability-driven engineering problems. Furthermore, weak alignment between HEIs and external innovation infrastructures limits the translation of creative ideas into viable entrepreneurial ventures.

Together, these barriers highlight the need for structured, experiential, and sustainability-oriented pedagogies that integrate technical expertise with entrepreneurial and collaborative competencies. The next section therefore examines four pedagogical frameworks: PBL, TEL, Jigsaw collaborative learning, and international or interdisciplinary teamwork, and analyzes how each can address these challenges and contribute to sustainable technopreneurial competence development.

4. Pedagogical Frameworks Enabling Sustainable Technopreneurship in Engineering Education

Building on the challenges identified earlier, this section examines pedagogical approaches that can address the structural and instructional limitations of technopreneurship education in engineering. Contemporary research emphasizes the importance of experiential and collaborative learning environments that promote creativity, sustainability awareness, and real-world problem-solving [

18,

23,

25,

26]. Four pedagogical frameworks stand out for their relevance and frequency of application within HEIs: PBL, TEL, Jigsaw collaborative learning, and international or interdisciplinary teamwork. Together, these approaches foster the creation of conditions supporting authentic learning and sustainability-oriented competency development across innovation, strategy, collaboration, and global awareness domains.

4.1. Project-Based Learning

PBL engages engineering students in authentic, open-ended projects where they integrate technical knowledge with entrepreneurial action, scoping problems, iterating prototypes, and validating feasibility with users and stakeholders [

17,

19,

22,

24,

27,

28]. In a sustainability-oriented context (e.g., energy efficiency, circular materials, eco-design), PBL pairs engineering design with impact criteria (environmental and social), strengthening students’ ability to craft viable, responsible innovation aligned with SDGs and engineering program outcomes [

27,

29,

30,

31].

Evidence shows PBL can increase creativity, self-efficacy, and venture readiness, including students’ motivation to pursue start-ups or commercialization in deep-tech contexts [

19,

24,

28]. Without these supports, projects risk remaining superficial and disconnected from sustainability objectives [

26]. Thus, PBL serves as a foundational framework for sustainable technopreneurial competence, provided it is well-sequenced, resourced, and evaluated using authentic performance criteria.

4.2. Technology-Enhanced Learning

TEL integrates digital tools, platforms, and data-rich environments (e.g., collaboration suites, simulations, cloud services, virtual pitching) to extend experiential entrepreneurship learning beyond classroom constraints [

32,

33,

34,

35]. In technopreneurship, TEL enables scalable access to global expert networks and entrepreneurial ecosystems, supports iterative feedback and rapid experimentation, and can reduce resource intensity (e.g., virtual prototyping), aligning with sustainability principles and inclusive access [

32,

36,

37]. By integrating cloud services and virtual prototyping, TEL enhances both efficiency and inclusivity, reducing barriers to participation while promoting resource-conscious learning [

38].

TEL also supports international collaboration (asynchronous teamwork, shared workspaces) and structured, context-rich activities that improve opportunity evaluation and entrepreneurial mindset, relevant to deep-tech feasibility and impact framing [

33,

36,

37]. However, its effectiveness depends on pedagogical design rather than technology availability. When implemented within constructivist and interactive frameworks, TEL amplifies sustainability-oriented technopreneurship by combining accessibility, digital literacy, and evidence-based decision-making [

22,

32,

36,

37,

38].

4.3. Jigsaw Collaborative Learning

The Jigsaw model structures collaboration around distributed expertise and shared accountability. Students first specialize in a sub-domain (such as technological feasibility, market analysis, or sustainability assessment) and later integrate these insights within their teams [

39,

40]. This mirrors distributed expertise in deep-tech ventures and strengthens communication, leadership, and integrative problem-solving, competencies essential to sustainable engineering innovation where technical, market, and impact perspectives must converge [

40,

41,

42].

Empirical studies indicate that Jigsaw learning improves engagement, teamwork quality, and leadership skills while fostering self-efficacy and collective problem-solving [

41]. In technology-rich settings, Jigsaw supports knowledge transposition across technical and non-technical roles and can foreground impact criteria (e.g., stakeholder effects, environmental constraints) during reintegration phases [

42]. Its emphasis on inclusivity and collaboration aligns closely with sustainability education values [

39,

41].

4.4. International and Interdisciplinary Collaboration

International and interdisciplinary teamwork exposes students to diverse perspectives, market contexts, and regulatory environments, which are essential for global sustainability-oriented innovation [

43,

44,

45]. Such collaboration enhances students’ ability to manage complexity, navigate cultural diversity, and frame engineering solutions that are socially responsible and globally viable [

43].

Cross-domains projects (ICT + business; engineering + design) build teamwork, intercultural awareness, and entrepreneurial behavior while offering flexible blends of local and remote collaboration, and reducing mobility constraints [

44]. International exchanges develop global competencies and entrepreneurial attitudes, which transfer well to engineering, ICT, and business students working on sustainability-aligned ventures [

45]. Hybrid and virtual formats further expand participation while lowering the environmental impact of mobility [

36,

37,

38,

44]. These collaborations thus develop the intercultural awareness and ecosystem literacy required for sustainable technopreneurial practice.

4.5. Synthesis of Pedagogical Frameworks

To complement the qualitative synthesis presented in

Section 4.1,

Section 4.2,

Section 4.3,

Section 4.4, this subsection consolidates the empirical evidence from the reviewed studies addressing the four dominant pedagogical frameworks in technopreneurship-oriented engineering education. The aim is to provide a structured and partially quantitative overview (RQ3), indicating how these frameworks are distributed across study types and how frequently each methodological approach appears in the literature.

Table 1 and

Figure 2 summarizes the coded findings [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45], highlighting the methodological diversity and relative emphasis of each pedagogical model, which together form the empirical foundation for the competency-domain mapping discussed in

Section 5.

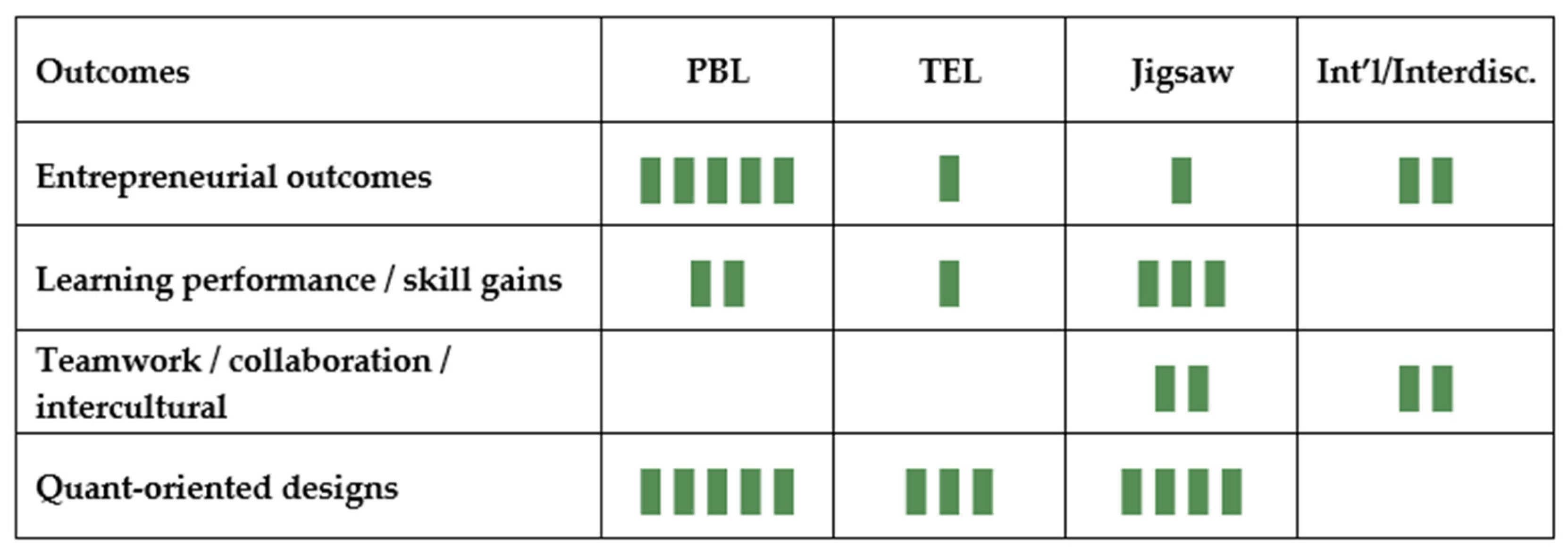

Table 2 and

Figure 3 summarizes the distribution of outcome categories identified across the reviewed studies [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45], showing how often particular learning or competency results were reported within each pedagogical framework.

The data show that entrepreneurial outcomes are reported most frequently in PBL studies, while learning performance and skill gains are most common in Jigsaw-based approaches. Teamwork and intercultural collaboration outcomes appear primarily in international or interdisciplinary contexts. Collectively, these quantitative patterns highlight the complementary strengths of the four pedagogical frameworks: PBL fosters entrepreneurial action and feasibility thinking; TEL expands digital access and experimentation; Jigsaw enhances teamwork and problem-solving; and international or interdisciplinary collaboration builds global and intercultural awareness. Together they provide a balanced foundation for sustainable technopreneurship education.

The synthesis presented above quantifies the scope and outcomes of current pedagogical approaches. Building on this empirical evidence, the next subsection integrates these findings conceptually to outline how the four frameworks interact and where their synergies emerge.

4.6. Towards an Integrated Pedagogical Perspective

The analysis of the four pedagogical frameworks reveals that each supports specific but complementary aspects of sustainable technopreneurship in engineering education. PBL is particularly effective in stimulating creativity, authentic problem-solving, and innovation-oriented mindsets. It enables students to translate technical expertise into tangible prototypes and venture concepts, thereby connecting learning with practical innovation outcomes. However, PBL’s potential depends on adequate support and access to infrastructures that ensure sustainability relevance and venture realism.

While PBL anchors experiential learning and provides a strong foundation for developing technopreneurial competencies, achieving comprehensive and sustainable outcomes requires additional pedagogical mechanisms that extend interaction, accessibility, and collaboration beyond the project setting.

TEL broadens the experiential scope of PBL by enabling global collaboration, continuous feedback, and digital experimentation. Its flexibility allows HEIs to engage students in entrepreneurial activities beyond institutional boundaries. When guided by appropriate instructional design, TEL promotes inclusion, accessibility, and efficient use of resources, which are key elements of sustainable learning environments.

While TEL enhances accessibility and continuity, developing the interpersonal and cognitive integration necessary for solving complex problems also requires pedagogical methods that emphasize structured collaboration and shared responsibility.

Jigsaw collaborative learning provides this integrative dimension. By distributing expertise across different teams and promoting mutual responsibility, it reflects the collaborative logic characteristic of real-world innovation processes. This model not only builds teamwork and communication skills, but also promotes recognition of diverse perspectives and shared responsibility, which are key to sustainable decision-making.

Beyond the internal dynamics of teamwork, preparing students for sustainable tech-nopreneurship also demands sensitivity to global contexts and the ability to operate across disciplinary and cultural boundaries.

International and interdisciplinary collaboration complements these approaches by situating learning within a global and culturally diverse environment. It encourages students to understand how innovation challenges differ across regions, markets, and regulatory frameworks. Such exposure strengthens global awareness, adaptability, and the capacity to co-create solutions that are both technologically viable and socially responsible.

Taken together, these four pedagogical strategies form a synergistic foundation for sustainable technopreneurship education. PBL anchors experiential learning; TEL expands its reach and inclusivity; Jigsaw ensures cognitive integration and teamwork; and international and interdisciplinary collaboration situates innovation within global sustainability contexts. Yet, as the literature indicates, the competencies developed through each framework remain uneven when implemented in isolation. This underscores the need for an integrated instructional approach that strategically combines their strengths.

The following section builds on this synthesis by analyzing how these pedagogies contribute to four core competency domains essential for sustainable deep-tech entrepreneurship: innovation and creativity, sustainability and impact orientation, entrepreneurial and strategic skills, and collaboration with global awareness. This mapping provides the analytical basis for identifying where pedagogical integration is most needed and lays the groundwork for the conceptual development of the Innovation and Technopreneur-ship Education Model (ITEM).

5. Sustainability and Deep-Tech Competencies in Engineering Education

Preparing engineers for sustainable technopreneurship requires capabilities that extend beyond technical knowledge and conventional business skills. Technology-intensive ventures operate in complex and uncertain environments that demand responsible innovation, stakeholder engagement, and long-term sustainability thinking. Building on the pedagogical frameworks discussed in the previous section, four interconnected competency domains emerge as essential for sustainable deep-tech entrepreneurship: (1) innovation and creativity, (2) sustainability and impact orientation, (3) entrepreneurial and strategic skills, and (4) collaboration and global awareness.

These domains synthesize insights from PBL, TEL, Jigsaw collaborative learning, and international or interdisciplinary collaboration—each contributing through different mechanisms and instructional emphases. Understanding how these pedagogies align with specific competencies is critical for assessing their adequacy in supporting techno-preneurial learning outcomes in engineering education.

To substantiate these relationships,

Table 3 presents empirical evidence linking each pedagogical framework to the four competency domains identified above.

In order to provide a holistic comparison of competency coverage across the frameworks,

Table 4 summarizes the relative intensity of each pedagogy’s contribution to sustainable technopreneurial competencies using a three-level shading scale derived from the reviewed literature. Dark green indicates strong support, medium green indicates moderate support, and light green denotes limited support for competency development.

The comparison demonstrates that, while all four pedagogical frameworks contribute to each competency domain, their intensity and focus vary considerably. PBL strongly supports innovation and impact-oriented engineering through authentic project engagement but often requires additional scaffolding to strengthen strategic and global competencies [

17,

19,

22,

24,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. TEL facilitates strategic and globally networked skills, promoting digital experimentation and ecosystem engagement, though its success depends on effective instructional design [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. Jigsaw collaborative learning enhances teamwork, integrative problem-solving, and shared responsibility, competencies that are central to sustainability-oriented projects [

39,

40,

41,

42]. International and interdisciplinary collaboration builds global awareness, cross-cultural communication, and the ability to frame market-relevant innovations responsibly [

43,

44,

45].

When examined together, these findings reveal that the pedagogical frameworks are mutually reinforcing rather than substitutive. PBL and TEL strengthen experiential and digital innovation capabilities, while Jigsaw and international collaboration foster inter-personal, cultural, and integrative competencies. However, the literature shows that each pedagogy, when applied in isolation, provides only partial coverage of the competencies needed for sustainable deep-tech venture development.

This mapping underscores the need for integrated pedagogical designs that combine these complementary approaches into coherent learning pathways. Such integration would ensure balanced competency development across innovation, sustainability, strategy, and collaboration. The next section builds on this synthesis by identifying key research gaps that currently limit progress toward achieving these outcomes in engineering technopreneurship education.

6. Discussion and Research Gaps

Building on the competency mapping presented in the previous section, it becomes evident that current pedagogical approaches, though valuable, do not yet form a coherent or sustainability-aligned system. While

Section 3 described persistent practical challenges in the delivery of technopreneurship education, the synthesis in

Section 4 and

Section 5 highlights several underexplored areas in current research that limit progress toward sustainability-aligned deep-tech venture development.

Gap 1—Limited development of structured, multi-phase learning pathways for deep-tech contexts

Most interventions remain isolated or short-term, providing insufficient scaffolding for progressive competency development from ideation to validation [

46,

47]. Existing studies often propose redesigned courses or local innovations rather than holistic learning pathways embedded into full engineering programs [

11,

48]. Research could further examine how multi-stage models can cultivate sustainable deep-tech readiness [

13,

49].

Together, these observations suggest that while progress has been made in creating isolated innovation experiences, a broader pedagogical vision that integrates sustainability and long-term development is still missing.

Gap 2—Underexplored integration of sustainability and responsible innovation

Although sustainability principles are increasingly included in engineering curricula, their systematic adoption in entrepreneurship learning remains sporadic [

45,

50]. Studies rarely examine how environmental, social, and ethical aspects influence real venture decisions or technology scalability under SDG constraints [

51]. Further research is warranted to embed measurable sustainability outcomes in entrepreneurial processes [

35].

The limited incorporation of sustainability principles also reflects a wider fragmentation in research, where pedagogical approaches are often examined independently rather than as part of a cohesive instructional system.

Gap 3—Fragmented understanding of pedagogical synergies

Empirical work typically investigates PBL, TEL, Jigsaw, and international/interdisciplinary learning independently [

22,

43,

44,

52], limiting insight into combined effects on sustainable innovation competencies. For instance, the use of Jigsaw remains mainly confined to technical or vocational subjects [

20,

21,

41,

42]. The synergy potential of these frameworks in deep-tech venture creation thus remains underexplored. As these methods are rarely combined or studied in relation to one another, assessment practices have likewise remained narrow, focusing on individual outputs rather than integrated learning outcomes.

Gap 4—Emerging assessment approaches for experiential and sustainability-aligned learning

Assessment still frequently emphasizes theoretical business knowledge over iterative creation, market experimentation, or sustainability impact [

53,

54]. There is limited understanding of how to measure complex competencies such as opportunity recognition, resilience, and responsible design within authentic engineering settings [

31,

55].

Gap 5—Partial alignment with innovation ecosystems and incubation dynamics

Research acknowledges collaboration needs, but published models rarely capture constraints typical for early-stage deep-tech development, including TRLs, prototyping cycles, or multi-stakeholder sustainability trade-offs [

2,

56]. There is also scope to examine digital and hybrid methods to connect students with global entrepreneur ecosystems while reducing access barriers and environmental costs [

57,

58].

Taken together, these gaps demonstrate that current technopreneurship education remains fragmented, methodologically narrow, and insufficiently aligned with sustainability and innovation ecosystems. The challenges, ranging from the absence of structured learning pathways to the weak integration of sustainability principles and pedagogical synergies, reveal the need for a more systemic instructional framework. Advancing the field requires longitudinal, evidence-based models that connect learning across stages, integrate complementary pedagogies, and align educational outcomes with real-world innovation contexts. Addressing these interrelated issues provides the conceptual foundation for the ITEM, conceptually outlined in the next section as a framework for uniting sustainability-oriented learning, entrepreneurial competence, and ecosystem engagement.

7. Future Directions for an Integrated Technopreneurship Education Model

Having in mind the research gaps identified in the previous section, this study proposes the ITEM as an integrated instructional framework that aligns engineering education with sustainability-oriented innovation. The model addresses the fragmentation found in current pedagogical practices by combining complementary teaching strategies focusing on PBL enhanced by TEL and conducted as Jigsaw collaborative learning, and international or interdisciplinary teamwork into a coherent, multi-stage learning pathway.

ITEM is structured around three interrelated dimensions that collectively support sustainable technopreneurship in engineering education:

- 1.

Pedagogical Frameworks Integration

This dimension combines the strengths of the four pedagogical frameworks. PBL provides experiential grounding; TEL expands digital access and feedback; Jigsaw structures knowledge integration and collaboration; and international or interdisciplinary teamwork situates learning within global and cross-sectoral contexts. Together, they form a structure-based ecosystem that enables continuous learning from idea to project implementation.

- 2.

Competency Alignment

ITEM explicitly maps these pedagogies onto the four competency domains defined in

Section 5: innovation and creativity, sustainability and impact orientation, entrepreneurial and strategic skills, and collaboration with global awareness. The model ensures balanced development by sequencing pedagogical methods according to the learning outcomes associated with each domain. For instance, PBL drives creative ideation and prototype development, while Jigsaw and international collaboration reinforce teamwork, ethical reasoning, and cross-cultural adaptability.

- 3.

Ecosystem Connectivity

This dimension embeds interaction with external stakeholders (industry, incubators, and global innovation networks) through digital and hybrid modalities. It ensures that learners experience authentic entrepreneurial processes, including market validation, sustainability assessment, and ecosystem feedback. TEL plays a central role in sustaining these interactions and supporting scalable, low-footprint collaboration.

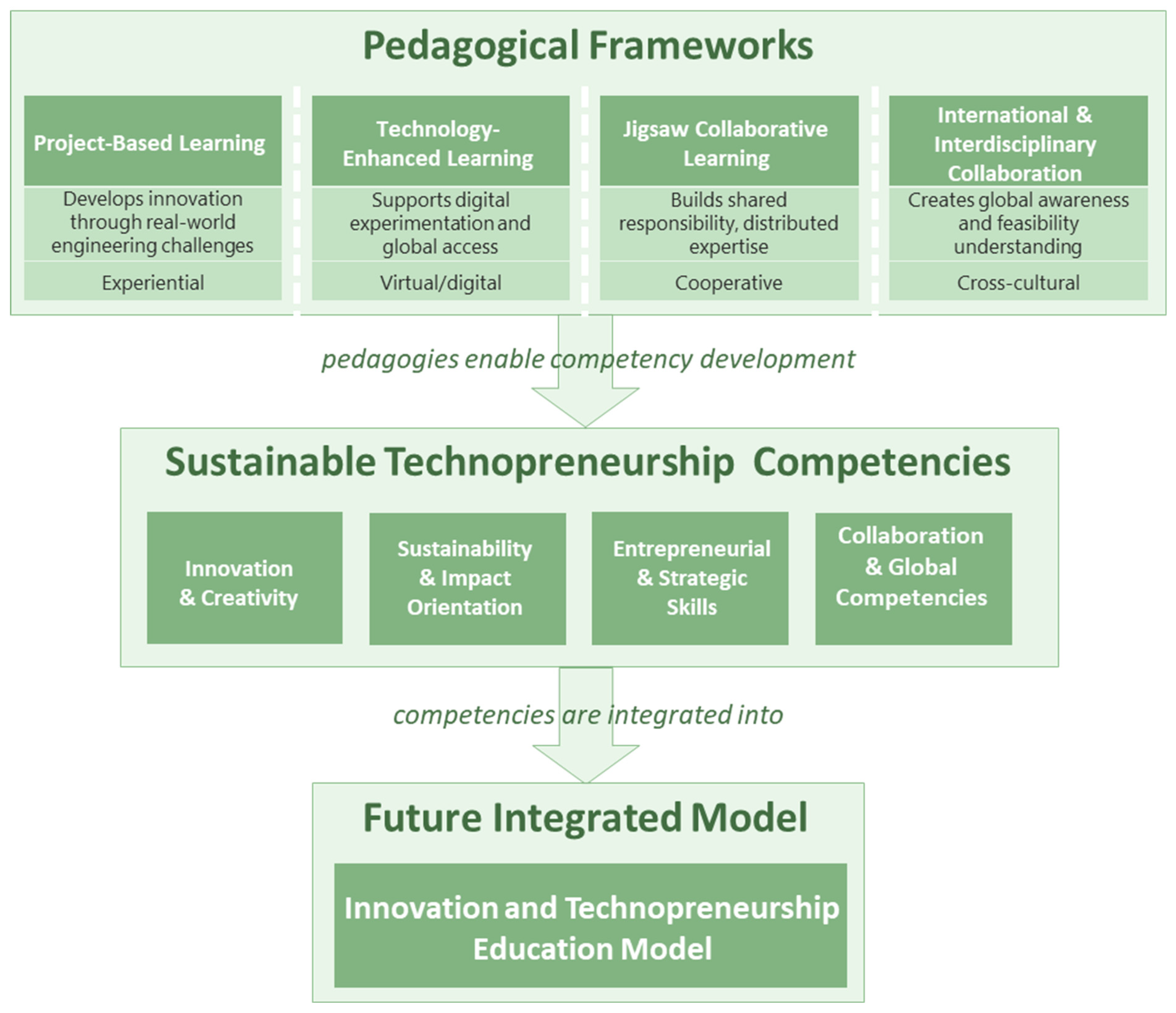

To synthesize these elements,

Figure 4 provides a visual representation of the ITEM pathway, illustrating how the three dimensions integrate into a coherent model for sustainability-oriented technopreneurship education. To emphasize the sequential logic of the model, the figure also shows how the pedagogical frameworks serve as inputs that cultivate key technopreneurship competencies, which in turn form the foundation of the proposed integrated ITEM.

Integrating these dimensions, ITEM transforms technopreneurship education from a set of isolated initiatives into a systemic process that mirrors real innovation cycles. It aligns curricular design with sustainability principles, promotes interdisciplinary collaboration, and fosters long-term engagement with technological ecosystems.

The model’s structure allows adaptation across institutional contexts, enabling HEIs to apply it as a comprehensive program framework or through modular integration within existing curricula. ITEM thus serves both as a conceptual synthesis and a practical roadmap for designing learning environments that nurture responsible deep-tech entrepreneurship.

Future research should focus on empirically validating the model through case studies, longitudinal implementations, and cross-institutional comparisons. Such evidence will refine ITEM’s structure and demonstrate its capacity to advance sustainability-aligned innovation in engineering education.

8. Conclusions

As engineering education evolves to meet the demands of rapid technological change and sustainability transitions, the development of technopreneurial capability has become an essential educational priority. Addressing RQ1 (examination of the educational contributions and limitations of the four pedagogical approaches most frequently discussed in the literature), this review synthesized evidence on PBL, TEL, Jigsaw collaborative learning, and international or interdisciplinary teamwork as the most consistently represented pedagogical strategies in technopreneurship-oriented engineering education. These approaches represent the most established and empirically supported pathways for fostering innovation, feasibility reasoning, and global collaboration in deep-tech contexts.

In response to RQ2 (how these approaches support the development of key competencies for sustainable technopreneurship), the comparative analysis showed that each pedagogy supports distinct yet complementary dimensions of sustainable technopreneurial learning. PBL most effectively develops creativity, applied innovation, and entrepreneurial initiative; TEL enhances digital literacy, accessibility, and scalability; Jigsaw strengthens teamwork and integrative problem-solving, while international and interdisciplinary collaboration builds global and intercultural awareness. However, the integration of sustainability principles within these pedagogies remains uneven, underscoring the need for stronger curricular embedding and assessment of impact-oriented competencies.

Regarding RQ3 (the extent to which current literature integrates sustainability, entrepreneurship, and collaboration themes), the quantitative synthesis revealed that entrepreneurial outcomes are the most frequently addressed, whereas collaboration and global competence receive comparatively limited empirical attention. Sustainability remains the least operationalized theme, pointing to a continuing imbalance between economic and socio-environmental dimensions of technopreneurship education. These results highlight the importance of cross-framework integration and more systematic evaluation of learning outcomes to achieve balanced competency development.

Finally, addressing RQ4 (the conceptual gaps that motivate the need for an integrated framework such as ITEM), the findings collectively provide both the empirical grounding and conceptual rationale for the proposed model. ITEM is envisioned as a multi-stage instructional framework that integrates the strengths of existing pedagogies, embeds sustainability across learning pathways, and aligns technopreneurship education with innovation ecosystem dynamics. By consolidating current evidence, identifying critical gaps, and outlining a coherent direction for future research and practice, this study contributes to advancing sustainable technopreneurship education in engineering and preparing future engineers to translate advanced technologies into solutions with lasting social, environmental, and economic impact.

Limitations and Future Work

This review has several methodological and conceptual limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the selection of the four pedagogical frameworks (PBL, TEL, Jigsaw, and international/interdisciplinary teamwork) was guided by their recurrent presence in the recent literature and their relevance to the development of sustainable technopreneurship competencies, rather than by a comparative analysis of all possible pedagogical alternatives. Therefore, this review does not claim that these approaches are objectively more significant or superior to others, but that they are the most conceptually suitable for the synthesis undertaken in this article. This should be interpreted as a scoping limitation rather than an assertion of pedagogical preeminence.

Second, the review is limited by its restricted temporal scope (2018–2025), which prioritises recent developments aligned with the acceleration phase of the SDG. While this focus supports the study’s orientation toward contemporary sustainability competencies, it necessarily excludes earlier pedagogical traditions that may also hold relevant insights.

Third, the synthesis relies on a relatively modest sample of 29 studies, which provides a representative but not exhaustive view of current practices. This limitation restricts the possibility of generalizing quantitative tables and suggests the need for future reviews with broader scopes or more systematic search procedures.

Future research should also explore additional pedagogical approaches, extend the temporal range, and validate the framework–competency relationships identified here through cross-institutional or longitudinal studies.

As the first stage of the broader ITEM research program, this review does not yet include integrated model deployment or measurements of student learning outcomes. These components will be addressed in the next stages, which involve designing and piloting the integrated strategy in engineering programs and conducting empirical evaluation of its effects on sustainable technopreneurial competency development. This staged progression will enable systematic validation and refinement of the conceptual contributions introduced here.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H., M.R., D.K.-V., M.U. and M.W.; methodology, J.H., M.R., D.K.-V., M.U. and M.W.; validation, J.H., M.R., D.K.-V., M.U., M.C., M.M. and M.W.; investigation, J.H., M.R., D.K.-V., M.U., M.C., M.M. and M.W.; resources, J.H., D.K.-V. and M.U.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H. and D.K.-V.; writing—review and editing, J.H., M.R., D.K.-V., M.U., M.C., M.M. and M.W.; visualization, J.H.; supervision, J.H., D.K.-V. and M.U.; project administration, J.H., M.R., M.C. and M.M.; funding acquisition, J.H., M.R., D.K.-V., M.C., M.M. and M.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the IDEATION (“Innovation and entrepreneurship actions and training for higher education”) project (ID: 1143) under the EIT HEI Initiative, supported by EIT Manufacturing, coordinated by EIT Raw Materials, and funded by the European Union. This work was partially supported by the DEETECHTIVE (“Deep Tech Talents—Innovation & Entrepreneurship Support”) project (ID: 10049) under the EIT HEI Initiative, supported and coordinated by EIT Raw Materials, and funded by the European Union.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study, the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HEIs | Higher Education Institutions |

| ITEM | Innovation and Technopreneurship Education Model |

| PBL | Project-Based Learning |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| TEL | Technology-Enhanced Learning |

References

- Weilerstein, P.; Byers, T. Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Engineering Education. Adv. Eng. Educ. 2016, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Holzmann, P.; Hartlieb, E.; Roth, M. From Engineer to Entrepreneur—Entrepreneurship Education for Engineering Students: The Case of the Entrepreneurial Campus Villach. Int. J. Eng. Ped. 2018, 8, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, J.W.; Rafferty, K.; Anderson, N.; Galway, L. A Cross-Discipline Technopreneurship Course: Student Perceived Benefits and Considerations. Proc. of the 2024 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), Washington, DC, USA, 13–16 October 2024; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosyadhi, M.; Ghina, A. The relevance of entrepreneurship learning processes towards technopreneur competencies within higher education institutions. In Digital Economy for Customer Benefit and Business Fairness; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rafiana, N.N. Technopreneurship Strategy to Grow Entrepreneurship Career Options for Students in Higher Education. ADI J. Recent Innov. 2024, 5, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyany, R.; Muhammad, S.; Geumpana, T.A.; Halim, H.; Amiren, M.; Muslim, M.; Dwi Pertiwi, C. A Potential Framework for an Impactful Technopreneurship Education. Indones. J. Bus. Entrep. 2023, 9, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, Y.; Mahmood, Z. Technopreneurship Education: The Way to Rebuild COVID-19 Affected Economy. J. Manag. Res. 2022, 9, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutrisno, S. The Role of Technopreneurship Education in Increasing Student Entrepreneurial Interest and Competence. J. Minfo Polgan 2023, 12, 1678–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, S.; Dhir, S. The evolving relationship of entrepreneurship, technology, and innovation: A topic modeling perspective. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2023, 14657503231179597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Murthy, V.; Tiwari, A.A. Digital Entrepreneurship: Foundations, Trends, and Future Directions. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2025, 44, 69–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryanti, N.; Nor, M.; Maziah, S.; Rahman, A.; Hayati, Y.; Naziman, N.M.; Norbaya, S.; Rashid, M.; Farleena, N.; Aznan, M. Revamping Technopreneurship Education in Public Higher University. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 1354–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewantara, H.; Kemalasari, A.A. The Role of Technopreneurship Literacy and Entrepreneurship Education in Fostering Entrepreneurial Interest Through Self-Efficacy. Pinisi J. Entrep. Rev. 2024, 2, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, Y.I. Technopreneurship and Work Motivation: The Key to Job Readiness of Information Technology Science Students in the Digital Era. Proceeding Int. Semin. Stud. Res. Educ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 2, 353–361. [Google Scholar]

- Labis, F.A. Mainstreaming Technopreneurship in Selected Higher Education Degree Programs. Liceo J. High. Educ. Res. 2016, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomani, M.; Gamariel, G.; Juana, J. University strategic planning and the impartation of technopreneurship skills to students: Literature review. J. Gov. Regul. 2021, 10, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alias, M.N.; Shamsudin, M.F.; Majid, Z.A.; Hakim, M.N. Technopreneurship and Digital Era in Global Regulation. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference of Interdisciplinary Sciences, Athens, Greece, 20–22 July 2020; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Y.M.; Lee, W.P.; Lim, T.M. Entrepreneurial and Commercialization Pathway through Project-based Learning in Higher-Education. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Education (TALE), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 10–13 December 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal, K.A.A.; Ihiabea, S.A.; Kazeem, S.O.; Andrew, M.K. Enhancing Sustainable Quality Education and Entrepreneurship Learning Skills in National Open University of Nigeria. J. Contemp. Educ. Res. 2025, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayati, K. Project-Based Learning in Teaching Entrepreneurship: A Review of the Literature. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference of Economics, Business, and Entrepreneurship, ICEBE 2021, Lampung, Indonesia, 7 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, W.-L.; Benson, V. Jigsaw teaching method for collaboration on cloud platforms. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2022, 59, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.B. Cooperative learning in computer programming: A quasi-experimental evaluation of Jigsaw teaching strategy with novice programmers. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 4839–4856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harahap, M.A.K. The Importance of Project-Based Learning in Student Entrepreneurship Edecation. Indo-MathEdu Intellect. J. 2023, 4, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badzińska, E. Experiential and result-driven entrepreneurship education: Evidence from an international project. Przedsiębiorczość-Eduk. 2021, 17, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afriasih, M.; Watye, R.; Azir, I. Increasing Independence and Entrepreneurial Interest via Project-Based Entrepreneurship Learning. In Proceedings of the First Jakarta International Conference on Multidisci-Plinary Studies Towards Creative Industries, JICOMS 2022, Jakarta, Indonesia, 16 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Manske, S. Managing Knowledge Diversity in Computer-Supported Inquiry-Based Science Education. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik-Kozłowska, B.; Kozłowski, R. Overcoming Challenges in Project-Based Learning: Educator Reflections on Interdisciplinary Coordination and Pedagogical Shifts in Entrepreneurship Education. In Proceedings of the Education Innovations—Motivation, Technology, and Pedagogical Strategies: 44EDU 2024, Granada, Spain, 27–28 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Łobacz, K.; Matuska, E. Project-Based Learning in Entrepreneurship Education: A Case Study-Based Analysis of Challenges and Benefits. Przedsiębiorczość-Eduk. 2020, 16, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, R.; Zitha, I.; Mokganya, G.; Molaudzi, V.; Nekhubvi, V.; Matsilele, O. Project-based learning for promotion of entrepreneurial education among first level science students. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaerunnisa, S.; Fauziyah, A.; Nurfitriya, M. The Effect of Project-Based Learning Method on Creative Problem-Solving in Students of the Entrepreneurship Study Program, Indonesian University of Education. J. Indones. Sos. Teknol. 2024, 5, 1464–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiawan, M.; Edosomwan, H.S.; Oktaria, S.D.; Viona, E. Entrepreneurial skill development in Indonesia and Nigeria through project-based learning. JPPI (J. Penelit. Pendidik. Indones.) 2021, 7, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujala, I.; Nyström, A.-G.; Wendelin, C.; Brännback, M. Action-Based Learning Platform for Entrepreneurship Education—Case NÅA Business Center. Entrep. Educ. Pedagog. 2022, 5, 576–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulistianingsih, S. Use of Digital Technology to Support the Entrepreneurship Education Process. Indo-MathEdu Intellect. J. 2023, 4, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagias, I.; Retalis, S. Secondary school students build multiple skills in evaluating business opportunities via technology-enhanced learning activities. Entrep. Educ. 2020, 3, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, D.F.; Sufyan, D.M.; Begum, D.M. Enhancing Entrepreneurial Mindset through Technological Integration in Higher Education in Pakistan. Acad. Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2025, 4, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoneva, L. Specificities of technology-enhanced learning in technology and entrepreneurship. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Recent and Innovative Results in Engineering and Technology, Kuala Terengganu, Malaysia, 10–11 July 2023; pp. 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulaudzi, I.C. The Role of Technology-enhanced Learning (TEL) and eSkills in Higher Education: Challenges, Opportunities, and Future Directions. Noyam J. 2025, 5, 3446–3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sree, V.S. Global Significance of Technology Enhanced Learning and Teaching. Power Syst. Technol. 2024, 48, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Xie, M. Technology Configuration of Innovation and Entrepreneurship Platform Based on Cloud Computing. In Proceedings of the 2022 7th International Conference on Cyber Security and Information Engineering (ICCSIE), Brisbane, Australia, 23–25 September 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya-capoccı, S. Teaching Entrepreneurship Through Innovative Approaches: An Educator’s Pedagogical Perspective. Adıyaman Üniversitesi Sos. Bilim. Enstitüsü Derg. 2022, 43, 166–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaenal, F.; Darsan, D.; Intyas, E. The Effect of the Implementation of the Jigsaw Model On Students’ Motivation and Learning Outcomes in the Subject of Entrepreneurship at Hidayatul Mubtadiin Vocational School. J. Educ. Technol. Inov. 2023, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi Moonaghi, H.; Bagheri, M. Jigsaw: A good student-centered method in medical education. Future Med. Educ. J. 2017, 7, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-M.; Huang, M.-Y. Enhancing programming learning performance through a Jigsaw collaborative learning method in a metaverse virtual space. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2024, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lans, T.; Oganisjana, K.; Täks, M.; Popov, V. Learning for Entrepreneurship in Heterogeneous Groups: Experiences from an International, Interdisciplinary Higher Education Student Programme. Trames J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2013, 17, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seruca, I.; Suilen, K.; Wijgergangs, L. Towards New Experiences for International Cooperation: A Multidisciplinary Ict and Business International Project. In Proceedings of the EDULEARN19 Proceedings, Palma, Spain, 1–3 July 2019; pp. 6808–6814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruti, A.; Paños-Castro, J. International entrepreneurship education for pre-service teachers: A longitudinal study. Educ. Train. 2020, 62, 825–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankesteijn, M.; Bossink, B.; van der Sijde, P. Science-based entrepreneurship education as a means for university-industry technology transfer. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 779–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daddi, D.; Boffo, V.; Buragohain, D.; Iyaomolere, T.C. Programmes and methods for developing entrepreneurial skills in higher education. Andragoške Stud. 2020, 2020, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleiman, Y. Integrating Technopreneurship Education in Nigerian Universities: Strategy for Decreasing Youth Unemployment. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 11, 49–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Long, Z.; Xu, D.; Zhu, R. How to Improve Entrepreneurship Education in “Double High-Level Plan” Higher Vocational Colleges in China. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 743997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machmud, R.; Wuryaningrat, N.F.; Mutiarasari, D. Technopreneurship-Based Competitiveness and Innovation at Small Business in Gorontalo City. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2022, 17, 1117–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kertiasih, N.; Setemen, K.; Permana, A. Content Development: Character-Based Technopreneurship Education for Young Ganesha Entrepreneurs. Asian J. Sci. Technol. Eng. Art 2024, 2, 744–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardana, W.; Heriyati, N.; Oktafiani, D.; Gaol, T. Importance of Technology-based Entrepreneurship in the Education. FIRM J. Manag. Stud. 2022, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschhäuser, M.; Riesel, F.; Bräutigam, V. Automated Competence Assessment Procedures in Entrepreneurship. Merits 2024, 4, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matyakubova, D.; Yakubov, A.; Javohir, S.; Zaripov, K. Methodological Approaches to Assessment of Entrepreneurial Ability. In Proceedings of the International Scientific and Practical Conference “Smart Cities and Sustainable Development of Regions” (SMARTGREENS 2024), Angers, France, 2–4 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Munoz, L.; Hurt, K.; Miller, R. Revising the Entrepreneur Opportunity Fit Model: Addressing the Moderating Role of Cultural Fit and Prior Start-Up Experience. J. Bus. Entrep. 2015, 27, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen, D.; Henderson, M.; Creely, E.; Ceretkova, S.; Černochová, M.; Sendova, E.; Sointu, E.T.; Tienken, C.H. Creativity and Technology in Education: An International Perspective. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2018, 23, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilderback, S.; Thompson, C.B. Developing global leadership competence: Redefining higher education for interconnected economies. High. Educ. Ski. Work-Based Learn. 2025. ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosienkiewicz, M.; Helman, J.; Cholewa, M.; Molasy, M.; Górecka, A.; Kohen-Vacs, D.; Winokur, M.; Amador Nelke, S.; Levi, A.; Gómez-González, J.F.; et al. Enhancing Technology-Focused Entrepreneurship in Higher Education Institutions Ecosystem: Implementing Innovation Models in International Projects. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).