Building a Village Education Community: A Case Study of a Small Agricultural High School in South Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Necessity and Purpose

1.2. Research Questions

- How does the VEC improve the quality of rural education?

- What is the background and current status of the VEC in South Korea?

- What are the key mechanisms through which the VEC promotes improvements in educational quality?

- What insights can be drawn from the experiences of Poolmoo School in South Korea for improving rural education in China?

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Education Community

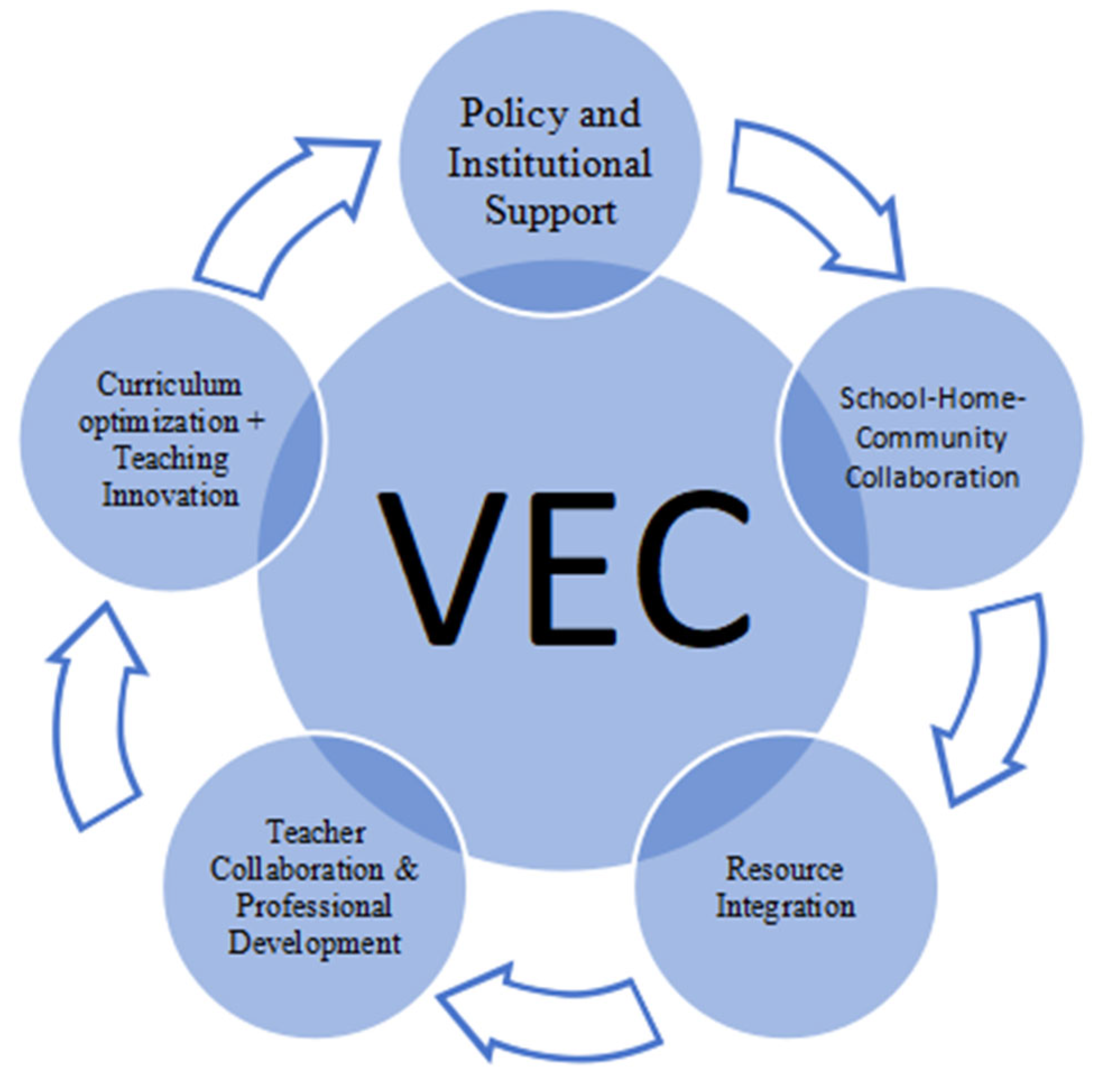

2.2. Village Education Community (VEC)

2.3. VEC Practices in South Korea

2.4. Education Quality

2.5. Rural Education Quality in China

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Qualitative Case Study Rationale

3.2. Research Site: Poolmoo School

3.3. Participants

3.4. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Findings

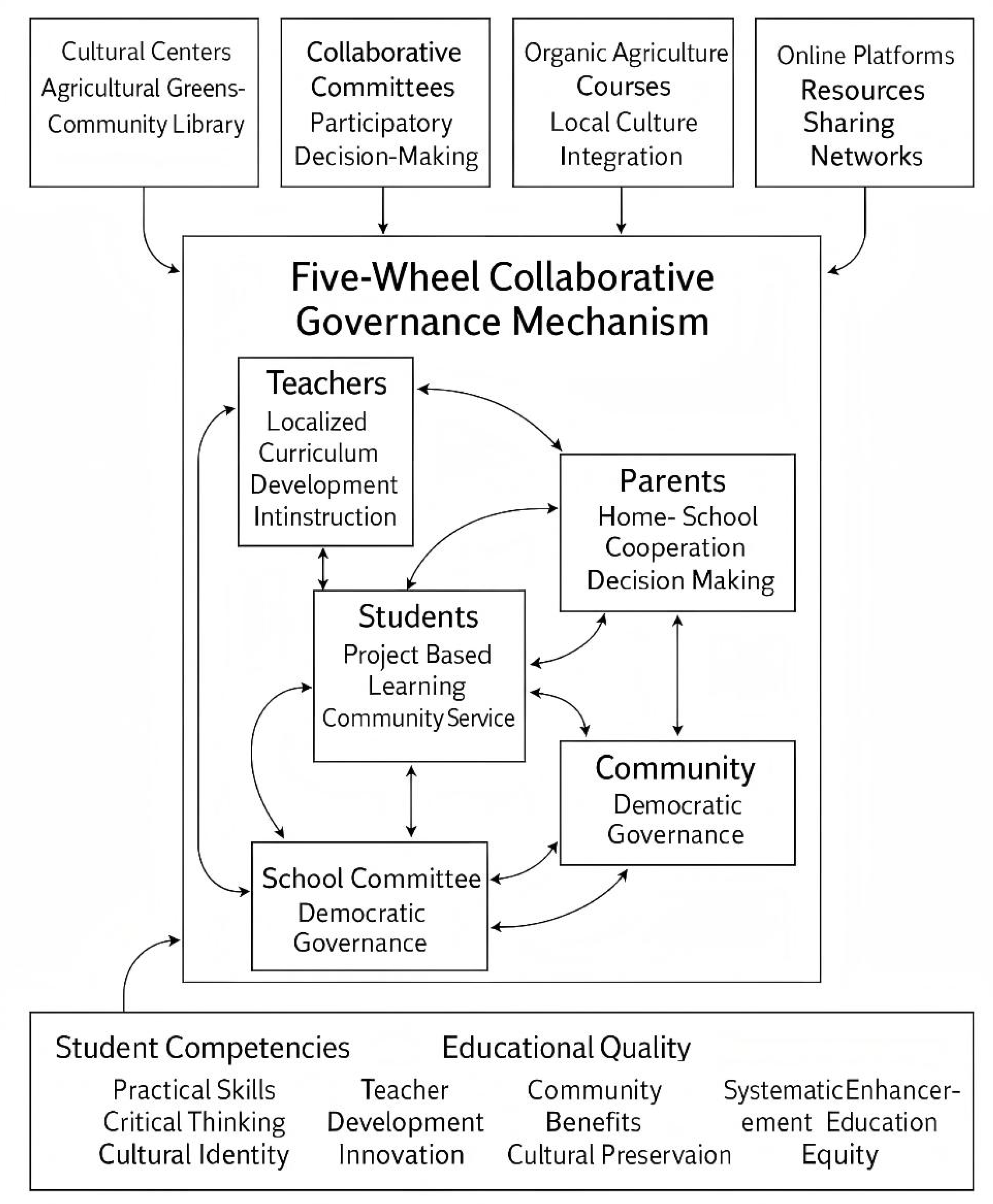

4.1. Five-Wheel Collaborative Governance

4.1.1. Conceptual Transformation

4.1.2. Student Competency Development

4.2. Challenges and Developmental Background of VEC in Korea

4.3. VEC-Educational Quality Relationship

4.4. Implications for China

4.4.1. Community Support for Teachers’ Professional Development

4.4.2. Multiple Evaluations of Students’ Comprehensive Literacy

4.4.3. Institutional Guarantee of Resource Integration

5. Discussion

5.1. The Improvement of Educational Quality

5.1.1. Cultural Embeddedness

5.1.2. Five-Wheel Collaboration Mechanism

5.1.3. Educational Cycles

5.1.4. Digital Leverage

5.2. Adaptability of Localized Applications

5.2.1. Policy

5.2.2. Culture

5.2.3. Local Applicability

6. Conclusions

6.1. Summary and Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Outlook

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, Y.; Li, X. Regional Inequality in China’s Educational Development: An Urban–Rural Comparison. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, B.; White, M.A.; McCallum, F. Exploring Rural Chinese Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Wellbeing: Qualitative Findings from Appreciative Semi-Structured Interviews. Int. J. Chin. Educ. 2022, 11, 2212585X2210928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Xie, Y. Study on the Path of Clustering Construction of Rural Primary Schools’ Aesthetic Education Programs from the Perspective of Resource Integration. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0317099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Gai, Y.; Zhang, A. A Study on the Professionalization of Young Part-Time Farmers Based on Two-Way Push–Pull Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.-T. School Communities Embracing Villages: Stories of School Communities Moving on Two Wheels—School and Village; Min-deulle: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2017. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H.; Ma, L. Embedding Local Cultural Richness in English Language Education: A Place-Based Dual-Core Approach for Rural Schools in China. Front. Educ. 2025, 10, 1580324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhou, J.; Liu, L.B.; Li, Q. Teacher Resilience Development in Rural Chinese Schools: Patterns and Cultural Influences. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2024, 147, 104656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-R. Exploratory Approach to the Principles of Community-Based Education Community Building. J. Educ. Adm. 2015, 33, 259–287. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Huang, R.; Liu, G.; Shrestha, A.; Fu, X. Social Capital in Neighbourhood Renewal: A Holistic and State of the Art Literature Review. Land 2022, 11, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brieant, A.; Burt, K.B. The Protective Role of Community Cohesion Across Rural and Urban Contexts: Implications for Youth Mental Health. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2025, 30, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hail, M.A.; Al-Fagih, L.; Koç, M. Partnering for Sustainability: Parent–Teacher–School (PTS) Interactions in the Qatar Education System. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Gao, J.; Yao, M.; Yao, S. The Impact and Mechanism of Neighbourhood Social Capital on Mental Health: A Cross-Sectional Survey Based on the Floating Elderly Population in China. BMC Geriatr. 2025, 25, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seoul Village Community Support Center. 2014 In-Depth Casebook of Village Communities: Looking Back at Our Village; Seoul Village Community Support Center: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2014. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. Teacher Development for Building Rural Educational Community: Liangjiachuan Primary School in Hubei. In New Pathways of Rural Education in China; Han, J., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, L.; Liu, M.; Ji, T.; Wu, X.; Li, Y. Design Reflections on the Integrated Development of Rural Cultural and Ecological Resources in China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, A.; Jahangir, Y.; Knutsson, S. Parent–School–Community Partnerships for Sustainable Education: Stakeholder Participation and Collaborative Governance Models in Western Contexts. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S. Seodang: A Pilgrimage Toward Knowledge/Action and “Us-ness” in the Community. Cogent Educ. 2018, 5, 1516498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Park, J.; Lee, S.W. The Impact of the Comprehensive Rural Village Development Program on Rural Sustainability in Korea. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, S.; Kim, K.-K.; Park, H. School Choice and Educational Inequality in South Korea. J. Sch. Choice 2012, 6, 158–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Global Education Monitoring Report 2020: Inclusion and Education—All Means All; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Unlocking High-Quality Teaching; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemons, R.; Jance, M. Defining Quality in Higher Education and Identifying Opportunities for Improvement. Sage Open 2024, 14, 21582440241271155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xue, E.; Cao, J.; He, Y.; Wu, Y.; Hou, H. Knowledge Mapping of the Rural Teacher Development Policy in China: A Bibliometric Analysis on Web of Science. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Rozelle, S. Teaching Training Among Rural and Urban In-Service Teachers in Central China. Educ. Res. Policy Pract. 2023, 22, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J. Endogenous Development and Ecological Capital Transformation: A Study of Green Economic Models in Anji, Zhejiang. In Proceedings of the 2025 11th International Conference on Humanities and Social Science Research (ICHSSR 2025), Beijing, China, 25–27 April 2025; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S.; Liebenberg, L. Qualitative Description as an Introductory Method to Qualitative Research for Master’s-Level Students and Research Trainees. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2024, 23, 16094069241242264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Zhou, J.; Shen, X.; Cullen, J.; Dobson, S.; Meng, F.; Wang, X. Rural Living Environment Governance: A Survey and Comparison Between Two Villages in Henan Province of China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hands, C.M. School–Community Collaboration: Insights from Two Decades of Partnership Development. In Schools as Community Hubs; Cleveland, B., Backhouse, S., Chandler, P., McShane, I., Clinton, J.M., Newton, C., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; SAGE Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Enworo, O.C. Application of Guba and Lincoln’s Parallel Criteria to Assess Trustworthiness of Qualitative Research on Indigenous Social Protection Systems. Qual. Res. J. 2023, 23, 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Han, J.; Kim, H. Exploring Key Service-Learning Experiences That Promote Students’ Learning in Higher Education. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2023, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Ye, C.; Hu, W. Effects of the Supervision Down to the Countryside on Village Public Goods Expenditure: Empirical Evidence from Rural China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shu, L.; Peng, L. The Hollowing Process of Rural Communities in China: Considering the Regional Characteristic. Land 2021, 10, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y. Students’ Career Intention to Teach in Rural Areas by Exploring the Factors of Teacher Shortage in Underserved Areas. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. Exploring the Third Type of Digital Divide for Primary and Secondary Education: Equity Implications of Online Learning. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Chan, C.K. Twenty Years of Assessment Policies in China: A Focus on Assessing Students’ Holistic Development. Int. J. Chin. Educ. 2023, 12, 2212585X231173135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. Rigidity’s Echo. ECNU Rev. Educ. 2023, 6, 447–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, E.; Li, J.; Li, X. Sustainable Development of Education in Rural Areas for Rural Revitalization in China: A Comprehensive Policy Circle Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruenewald, D.A. Foundations of Place: A Multidisciplinary Framework for Place-Conscious Education. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2003, 40, 619–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. Exploring the Path of Farming-and-Reading Education in Agriculture-Related Universities Under the Perspective of Rural Revitalization. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Growth Eval. 2024, 5, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, D.; Alkaher, I. Cultivating Environmental Citizenship: Agriculture Teachers’ Perspectives Regarding the Role of Farm-Schools in Environmental and Sustainability Education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron, N.L.; McLeskey, J. Establishing a Collaborative School Culture Through Comprehensive School Reform. J. Educ. Psychol. Consult. 2010, 20, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R. A Policy Analysis of the Development of Balanced Compulsory Education in Chinese Counties. Sci. Insights Educ. Front. 2023, 18, 2847–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Yang, Y. Education Informatization 2.0 in China: Motivation, Framework, and Vision. ECNU Rev. Educ. 2021, 4, 410–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.J. A Study on the Meaning and Nature of Local Community Lifelong Education. J. Lifelong Educ. 2006, 12, 53–80. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Elfert, M. Lifelong Learning in Sustainable Development Goal 4: What Does It Mean for UNESCO’s Rights-Based Approach to Adult Learning and Education? Int. Rev. Educ. 2019, 65, 537–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.L. Digital Empowerment for Rural Migrant Students in China: Identity, Investment, and Digital Literacies Beyond the Classroom. ReCALL 2025, 37, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Zhang, L. Ubiquitous e-Teaching and e-Learning: China’s Massive Adoption of Online Education and Launching MOOCs Internationally During the COVID-19 Outbreak. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2021, 2021, 6358976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J. Impact of Living Conditions on Online Education: Evidence from Low-Income Households in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Mao, X.; Wang, Z.; Feng, Y. The Impact of Digital Village Policy Implementation on the Innovation and Establishment of New Agricultural Operators: Evidence from China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1650488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Yue, W.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, F. Curriculum Leadership of Rural Teachers: Status Quo, Influencing Factors and Improvement Mechanism-Based on a Large-Scale Survey of Rural Teachers in China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 813782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Sun, T.; Gong, J.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Q. Remote Co-Teaching in Rural Classroom: Current Practices, Impacts, and Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 29 April–5 May 2022; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. The Synergized Quality Improvement Program in Teacher Education: A Policy for Improving the Quality of China’s Rural Teachers. ECNU Rev. Educ. 2024, 7, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H. Taking Grandparents to School: How School–Community–Family Collaboration Empowers Intergenerational Learning in China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, T. The Interdependence of Educational Alienation and Equality. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 2385770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xue, E.; You, H. Parental Educational Expectations and Academic Achievement of Left-Behind Children in China: The Mediating Role of Parental Involvement. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hesketh, T. Educational Aspirations and Expectations of Adolescents in Rural China: Determinants, Mental Health, and Academic Outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Liu, K.; Kang, L.; Behrman, J.R.; Richter, L.M.; Stein, A.; Lu, C. Assessing Household Financial Burdens for Preprimary Education and Associated Socioeconomic Inequalities: A Case Study in China. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2023, 7, e001971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Wang, X. Exploring Locally Developed ELT Materials in the Context of Curriculum-Based Value Education in China: Challenges and Solutions. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1191420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Duan, Y.; He, S.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, Q.; Miao, S. An Empirical Study of Situational Teaching: Agricultural Location in High School Geography. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Guo, X.; Chen, L. Exploration of the Cultural Connotation of “Traditional Festivals” Eco-Curriculum in Primary Schools. J. Contemp. Educ. Res. 2024, 8, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant | Position | Experience (Years) | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| PT01 | Senior Teacher | >10 | Leads school–community integration |

| PT02 | Teacher | 5–10 | Curriculum development |

| PT03 | Teacher | 5–10 | Parent cooperation |

| PT04 | Teacher | 5–10 | Community activity coordination |

| PT05 | Teacher | <5 | Digital education |

| PS01 | Student | — | Participates in community activities |

| PS02 | Student | — | Agricultural practice |

| PS03 | Student | — | Club leadership |

| PP01 | Parent | — | Home–school cooperation |

| PP02 | Parent | — | Community volunteer |

| PP03 | Parent | — | School committee member |

| PR01 | Resident | — | Community event organizer |

| PR02 | Resident | — | Local enterprise representative |

| Role | Number | Data Collection Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Teachers | 5 | Unstructured interviews and questionnaires |

| Students | 3 | Questionnaire survey, classroom observation |

| Parents | 3 | Unstructured interviews and questionnaires |

| Residents | 2 | Unstructured interviews and questionnaires |

| Coding | Core Tasks and Analyses | Key Output and Theoretical Conceptions |

|---|---|---|

| Open Coding | All the interview transcriptions, field notes and document materials were analyzed line by line to extract the initial concepts | “Parents participate in curriculum design”, “Community provides practice base”, “Teacher course autonomy”, etc., and preliminary labeling is carried out |

| Axial Coding | Discover and correlate the logical relationship between these initial concepts and classify them into higher-level categories | Categorize the above concepts as “resource integration mechanisms”, “democratic decision-making practices” |

| Selective Coding | In all the discovered categories, systematically identify and determine a “core category” that can overarch other categories | Core category: “Five-Wheel Collaborative Governance Mechanism.” Storyline is built and presented according to this category (i.e., the “Findings” part of this paper), clearly demonstrating how its subcategories (such as resource sharing, democratic autonomy, etc.) interact and collectively constitute the operational model of VEC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fan, Q.; Kang, Y. Building a Village Education Community: A Case Study of a Small Agricultural High School in South Korea. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11217. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411217

Fan Q, Kang Y. Building a Village Education Community: A Case Study of a Small Agricultural High School in South Korea. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11217. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411217

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Qianqian, and Youngtaek Kang. 2025. "Building a Village Education Community: A Case Study of a Small Agricultural High School in South Korea" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11217. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411217

APA StyleFan, Q., & Kang, Y. (2025). Building a Village Education Community: A Case Study of a Small Agricultural High School in South Korea. Sustainability, 17(24), 11217. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411217