5.1. Key Findings

This study provides a new perspective to the literature on the sustainability–finance interaction by examining the relationship between sustainability practices and profitability with a special focus on a particular crisis period (COVID-19). In this context, we analyze this relationship using data from 47 different stock exchanges over the 2020–2022 period, with up to 14,652 firm-year observations depending on the specification. We mainly investigate the impact of ESG score and its subscores (E, S, and G) as well as greenwashing (GW) on return on assets (ROA) and Tobin’s Q (TQ) based on difference-in-differences (DID) regressions. The results reveal the effects of sustainability practices on short- and long-term profitability, as well as the different dynamics observed during and after the crisis. Although existing studies have examined the relationship between certain sustainability practices (mostly for ESG and its subscores) and post-crisis profitability, the roles of economic development and public governance (apparent by voice and accountability) in shaping this profitability remain relatively unexplored. Motivated by this gap, we perform an empirical analysis on a large global dataset. Our findings provide important clues by explaining the impact of sustainability practices on post-crisis profitability through the mechanisms associated with country-specific dynamics (economic development and public governance), complemented by firm-level dynamics.

The first notable result (without differentiating by country groups) is that firms with a higher ESG score increased their operational performance and market value in the post-crisis period more than those with a lower ESG score. In this respect, our findings coincide with the findings of [

29], who find similar results, but for a limited sample (banking sector). Moreover, this positive effect holds not only for the first year after the crisis (2021), but also for the second year (2022). This result aligns with crisis theory, which posits that businesses are better positioned to recover from downturns when they concentrate on strengthening their organizational reputation and social legitimacy in those periods by developing a trust-based communication with stakeholders and managing their sustainability investments effectively [

2,

95]. It also confirms that organizational reputation and social legitimacy [

35,

36] may influence the extent to which firms with high ESG enhance post-crisis profitability, and the persistence of this effect in 2022 further corroborates this view. This probably stems from the fact that positive returns of corporate reputation and social legitimacy are likely to persist [

37], with increased investor confidence and strengthened image [

39]. Since firms gradually generate these positive outcomes by continuously layering their valuable activities over time, such intangible assets cannot be acquired immediately. Hence, supporting [

55,

100], this study confirms that it is necessary to examine lagged effects in order to properly assess the ESG–profitability relationship.

As for the ESG sub-dimensions, considering the increased stakeholder interest in ESG, it is not surprising that each sub-dimension had a direct positive impact on post-crisis profitability. In addition, among the subscores, E exhibits the highest correlation with profitability and the post-COVID-19 effect of E on both operational performance and market value is the most noticeable. Two potential reasons for this outcome are as follows. First, the descriptive statistics show that E scores are on an upward trend compared to S and G, but remained lower than S and G during the crisis period. This could mean that businesses are more likely to be rewarded for successfully implementing their realistic environmental pledges. Secondly, during the COVID-19 period, stakeholders started to pay more attention to environmental issues [

41] and allocated more funds to green investments as part of post-COVID-19 recovery policies (EU: “Green Deal”, US: “Green Recovery”). COVID-19 was expected to trigger a green recovery and the protection of the environment was a priority [

31]. Therefore, stakeholders might have placed greater emphasis on E-related issues than on S- and G-related ones.

This corresponds with the argument of the availability heuristic bias [

42], which holds that recent experiences (e.g., the pandemic) may have made some initiatives (e.g., environmental issues) more accessible, which leads stakeholders to assign disproportionately higher values to these initiatives. One possible explanation is that the availability bias may have shaped stakeholder behavior in this context, thereby magnifying the extent to which high E exerted a stronger effect on profitability than high S and G during the crisis period.

Unexpectedly, firms which were more engaged in GW during the crisis increased their ROA afterwards. This result contrasts with [

75], and contrary to [

47], supports the view that strict regulations with sanctions were limited or ineffective. With this finding, we partially support [

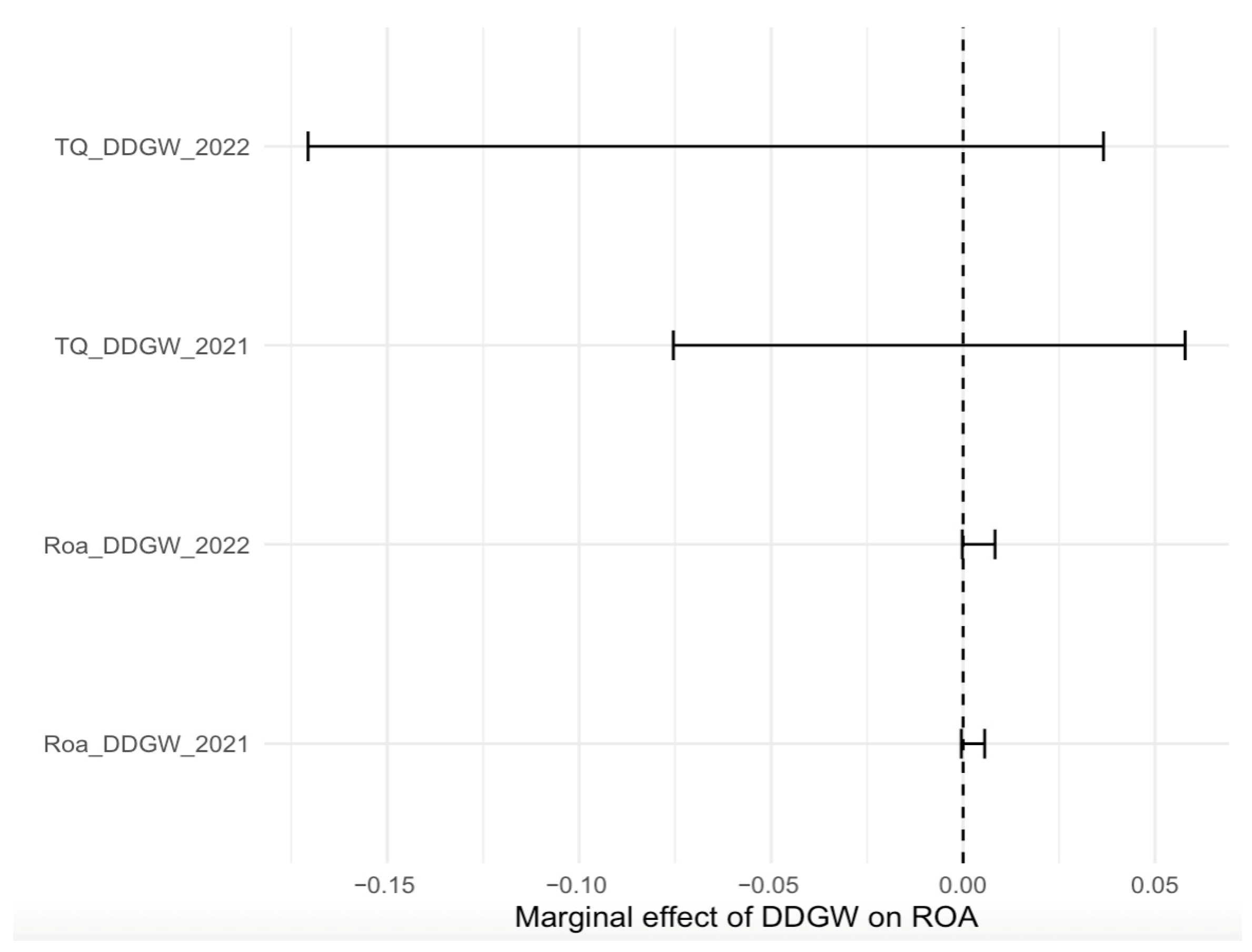

75] in that companies need to communicate about their environmental commitments (“negative effects of brownwashing on profits”) to some extent, even after crisis periods. Nevertheless, it should be noted that we also find mixed results for operational performance and market value in terms of post-crisis profitability. Specifically, although statistically insignificant, after controlling for the marginal effects in

Figure 1, we observe that high GW during crisis could also lead to substantial declines in post-crisis market value, a pattern that became more pronounced in the long run (2022). The lack of a significantly positive effect, as observed for ROA, is also consistent with—and partially supportive of—this view, which argues that stakeholder priorities and reactions are clearly visible in the GW–profitability relationship [

45,

46], especially in the long run with reputational risks [

33]. The fact that this effect becomes insignificant particularly for market value indicates that GW is a potentially reaction-eliciting practice, especially in the long run.

As for country effects, our results confirm that ESG can have different impacts on profitability depending on economic development, supporting [

101]. We find that firms in developed countries with high ESG scores during the crisis period had higher profitability in the post-crisis period than firms in developing countries with high ESG scores. The same results hold for the subscores (E, S, and G). This evidence may plausibly support the argument that stakeholders in developed countries are more likely to prioritize sustainability issues and more willing to pay for ESG issues [

52], while stakeholders in developing countries are more likely to focus on economic survival and short-term profitability [

51], especially in crisis periods.

During COVID-19, many companies experienced financial difficulties and were unable to survive, more prominently so in developing economies [

4,

38]. According to slack resources theory, when resources are limited, managers face trade-offs [

59]. Because of the trade-offs, the marginal benefit of sustainability practices on profitability may be more weakened in developing countries than in developed countries. A complementary view supporting our findings is offered by signaling theory, which argues that not all ESG signals are interpreted equally [

60]; ESG credibility depends on the institutional ecosystem in which they are issued. Given that credibility plays a central role in influencing stakeholders’ valuations, signaling theory provides additional support for our findings. Thus, drawing on the theoretical justifications provided by slack resources and signaling theories, we confirm that economic development significantly influences the relationship between ESG (alternatively E, S, and G) and post-crisis profitability.

In general, companies in developed countries that focused on the E, G, and S subscores achieved better profitability after COVID-19. Our results support the view that, during the COVID-19 period, stakeholders—especially investors in developed economies—placed greater emphasis on, and more strongly rewarded, environmental performance. According to [

38], during COVID-19, developing-country firms showed greater interest in S and G topics—such as employee health, stakeholder support, and transparency—than in E topics. Moreover, the strong emphasis placed on E-related issues in developed countries may be attributed to the comparatively stronger social and technological infrastructure which they possess. As shown in

Figure 1, although firms in developing countries achieved much higher E scores during the COVID-19 period, companies in developed countries attained higher levels of post-crisis profitability. Ultimately, this finding requires further research.

As for the GW–profitability relationship across developed and developing countries, we find that firms with high GW in developed countries generally obtained a higher post-crisis profitability than those in developing countries. This outcome contrasts with the view that public awareness, pressure, and lawsuits were more pronounced in developed economies, and therefore GW practices during COVID-19 would have been more penalized by the public than in developing economies. Because stakeholder pressure is higher on companies in developed countries, firms in developing contexts may consequently display higher GW values [

38]. Thus, the losses in legitimacy observed during COVID-19 may manifest more prominently in developing countries in the subsequent period, despite developed countries exhibiting higher levels of established legal systems and institutional infrastructures that may impose greater penalties on GW. This result might stem from the stronger corporate governance in developed-country firms which disguises their window dressing. Indeed, companies in developed countries might have turned the crisis into an opportunity despite strong regulatory pressures (e.g., the rise of GW in 2020 and the implementation of the EU taxonomy in July 2020). More specifically, companies in developed countries may have improved their post-crisis profitability because they better managed GW (e.g., complying with some regulations while avoiding others). GW practices in developed countries are managed in a way that does not provoke stakeholder backlash, even though there is more public pressure therein. In developed-country firms, GW practices seem to have worked better and increased visibility more without harming image. In other words, companies in developed countries might have masked their GW practices by highlighting the areas they wish to signal, as suggested by signaling theory [

60]. In summary, it seems that, even during a crisis period, strict policies against GW practices may not prevent firms performing GW and obtaining higher profitability and market value afterwards.

Furthermore, our findings uncover a well-defined governance mechanism through which sustainability practices influence post-crisis profitability, emerging from the differentiation of countries by their voice and accountability (V&A) levels. High V&A (HVA) countries typically exhibit higher levels of rights (e.g., electing their government, freedom of press, freedom of expression, and democratic participation), a pattern that has broader institutional and behavioral implications. Stakeholders in HVA countries tend to exert stronger pressure on sustainability-related issues than those in low V&A countries. Consequently, the stakeholder awareness of sustainability-related issues is likely to be relatively higher among HVA countries. For instance, the U.S.—which is a developed economy—is not among the countries with HVA. So, we expected that, compared to certain European countries (particularly given the increased regulations for sustainability activities in Europe), the pressure on companies to engage in sustainability practices would be lower therein. This, in turn, could lead to lower rewards for ESG and more penalties for GW. By contrast, in a HVA country like Switzerland, we anticipated the opposite pattern. Supporting this expectation, our results show that the impact of sustainability practices on profitability is substantially stronger in HVA countries than in others. While this effect is limited for GW, it is strongly evident for ESG and its subscores. These findings are consistent with the developed/developing country grouping; however, the coefficient magnitudes and significance levels are higher under this alternative grouping. This part of the study offers a more critical perspective, suggesting that various factors—such as institutional transparency, civil society pressure, and stakeholder awareness—shape the extent to which sustainability practices influence post-crisis profitability.

Similarly, when comparing the effect of GW on post-crisis profitability across these two country groups, we once more find a more pronounced impact—particularly for firms in HVA countries. The strong corporate governance or window dressing previously discussed for firms in developed countries may also account for this heightened positive effect on post-crisis profitability.

Our findings are consistent with [

79], which reports that ESG increases operational performance during crisis and that this relationship depends on a country’s income level. However, differing from this study, we show that economic development (DEV vs. EMG countries) and especially public governance (HVA vs. LVA countries), provide a better explanation for this relationship. Moreover, as a novelty for the literature, we find that GW during times of crisis might be beneficial for operational performance, yet represents a potentially reaction-eliciting practice that can decrease market value in the long run.

The results from the country groupings further indicate a stronger effect in developed (DEV) and high voice and accountability (HVA) countries, suggesting that the impact of GW on post-crisis profitability also depends on public governance. In summary, we find that having a high ESG during the crisis is beneficial for the post-crisis period; however, this outcome appears to be closely tied to different pillars (E, S, or G), firm-specific factors, and the economic development and public governance in the country. Conversely, GW during the crisis can be either beneficial or detrimental depending on the financial metric employed, and its influence on post-crisis profitability is shaped by both corporate and public governance.

For the recovery period, we expected the inverse of what we had expected for the COVID-19 year, i.e., we expected to find a lower 2022 profitability in DEV and HVA country firms having high ESG or high GW in 2021 than equivalent firms in EMG and LVA countries. We confirmed this result in the case of ESG when market value (TQ) is taken to show profitability, but not in others. In other words, we did not find any significant difference between developed and developing (or HVA and LVA) country firms in terms of the impact of ESG on operating performance (ROA) or the impact of GW on profitability (ROA or TQ).

These results indicate that, across country groups, having high ESG during times of crisis and during the recovery period can generate different outcomes in terms of subsequent profitability. According to crisis theory, investing in ESG may be more reasonable under uncertainty. Our findings suggest that this is particularly meaningful for firms in DEV and HVA countries. In contrast, during the recovery period, this appears to hold for companies in developing and low V&A countries. The insignificance of the results for GW during the recovery period can be explained by the increasing stringency of sustainability regulations over time. This finding requires further investigation.

With respect to the control variables, firm sizes display distinct patterns in relation to ROA and TQ. During COVID-19, larger (smaller) companies had an advantage to raise their operational performance (market value). Other control variables mostly yielded the same result for ROA and TQ. That is, high asset turnover, low leverage, and being young positively influenced profitability, while the evidence was weaker for number of board meetings and board gender diversity.

5.2. Managerial Implications

This research provides insights for scholars, managers, policymakers, business leaders, and investors by analyzing stakeholder perspectives during and after crises. It also provides insights for market representatives into how stakeholder participation in green practices differs among different country groups, and how these disparities may alter the relationship between sustainability practices and post-crisis profitability in crisis periods. From a scholarly perspective, a longitudinal approach with a high number of observations increases the potential for generalizability of the results and allows for additional insights when measuring the impact of sustainability practices on post-crisis profitability for companies from countries with different economic development or public governance. Our results basically support the stakeholder-centered view. In other words, increasing stakeholders’ awareness and knowledge about the long-term benefits of ESG and the short- and long-term damages of GW is important for companies to develop more accurate and effective sustainability strategies. This is evidenced by our results showing that ESG effects are more substantial in country groups with higher degrees of consumer awareness during the crisis.

This study offers various managerial implications in several aspects. We mainly conclude that robust sustainability strategies during crises not only enhance market value but also contribute to operational performance afterwards. Therefore, managers should support investments that have a direct impact on intangible assets such as ESG activities, especially in crisis periods. Companies should strategically retain high ESG scores during crisis periods, especially higher than their competitors. Under conditions of uncertainty, several critical risk factors arise. Investments like ESG that create important intangible assets like reputation and legitimacy can protect companies from financial risk [

92]. This is even more important in times of crisis and the outcome can be observed more in the long run, as suggested by crisis and resource-based theories.

These assets enhance firms’ ability to recover from crisis conditions [

5]. They are salient to stakeholders during and after the crisis and can significantly increase the company’s sustainable value in the long run. Managers should consider the long-term benefits (on ROA and TQ) of ESG in crisis periods, while not overlooking the long-term damage caused by GW (TQ). Despite the complexity of our findings regarding GW, marginal effects reveal that GW can sometimes reduce market value considerably. In crisis periods, stakeholders are more vulnerable to negative ESG news [

102]. Our results show that practices negatively affecting legitimacy and reputation (e.g., GW) during the crisis remained salient to the market and led to value reductions in the post-crisis period. Moreover, although ESG is beneficial in times of crisis, for effective ESG, managers should consider several factors like market position, stakeholder attitude, and stakeholder awareness. The variation in coefficients between the ROA and TQ models, along with the differences observed across different country groups, confirms this view. The Global Ethical Finance Initiative, assessing investors’ attitude in ESG matters, indicates that only 47% of investors in the Global South consider decreasing social inequality and injustice to be important, compared to 72% in the Global North. Our findings support GEFI [

103] findings by revealing that, in the aftermath of the crisis, investors assigned a lower value to ESG matters, more prominently in developing countries compared to developed ones, particularly regarding market value.

Moreover, according to our findings, not all subscores of ESG have the same impact on profitability after the crisis. So, managers should focus more on the sustainability issues linked to the company’s own identity without neglecting the nature of the crisis. The heightened attention to environmental issues (e.g., due to the underlying cause of the crisis) may have contributed to environmental scores exerting a stronger influence on the profitability in the post-crisis period.

The post-crisis profitability effect of sustainability practices shows strong variation regarding different country groups. Particularly in HVA countries, the significant positive impact of sustainability practices on post-crisis profitability is more prominent. Therefore, the influence of many institutional and stakeholder-related factors, such as institutional transparency, civil society pressure, and consumer awareness, should be taken into account in budgeting, requiring an integrated perspective [

61]. These factors are critical regarding the impact of sustainability practices on post-crisis profitability since they portray the underlying dynamics in the country group classifications.

Concerning subscores, E contributed to post-COVID-19 profitability more than G and S, particularly in developed countries. Slower and lower adaptation to new technologies or innovations in developing countries might increase pressure on costs, thereby resulting in lower post-crisis profitability from S and G compared to equivalent companies in developed countries.

For ESG, the moderating effects of economic development and voice and accountability provide a comparison between country groups (DEV vs. EMG or HVA vs. LVA). Managers should keep in mind that such investments, even for firms in developing or LVA countries, are linked to numerous benefits in crisis periods, which is important to ease corporate financing constraints [

104,

105] and reduce corporate risks.

Our findings show that, although ESG has long-term benefits and GW has long-term detriments (even if it generates short-term profits and the impact on market value is mixed), companies decide on their sustainability investment budgets also based on how much ESG is rewarded and how much GW is penalized in their host country or other countries (e.g., if it is doing business with a country that has sanctions). However, even though regulations are higher in some countries (e.g., EU countries: “EU taxonomy”), due to countries’ future sustainability agreements and plans, the gap is not expected to persist for long. Companies, especially in developing and low V&A countries, should develop sustainability strategies by taking this point into consideration.

Since our research includes macro dynamics, it provides important findings for policymakers. Some of our results (e.g., regarding GW) confirm that strict regulations with sanctions were limited or inadequate, especially in some countries, due to asymmetries in the regulation systems. In many countries (especially LVA countries), policymakers should increase sanctions and regulations and support companies with capacity-building programs and incentive mechanisms so that they can implement their sustainability strategies at the operational level. This is a crucial step in eliminating the long-term advantages and disadvantages between countries.

Furthermore, regardless of the impact of the crisis, developed and HVA countries should prioritize compliance with sustainability regulations, while developing and LVA countries should focus on mitigation (e.g., GW) and prepare for new regulations. Moreover, the attitude of developed or HVA countries towards other countries is critical since these countries are better positioned in terms of financing and technological infrastructure. In this context, policymakers in developed and HVA countries should cooperate with those in developing and LVA countries. Whether companies have the necessary incentives to adhere to a more efficient ESG and GW strategy mostly depends on resource availability and system infrastructure. Increasing incentives and regulations will cause companies to feel pressure for higher ESG and lower GW, especially those in developing and LVA countries, which has a direct impact on long-term profitability.

The relatively better performance of firms in developed and HVA countries regarding the impact of GW on post-crisis operational profitability supports that, even if stakeholder awareness is high in these countries, companies are mostly able to manage their unethical sustainability strategy without experiencing a public backlash. To prevent this, policymakers should build systems to monitor the reliability of sustainability information and should enhance the ease of accessing sustainability data for the public. Close communication with stakeholders improves corporate accountability, which also increases pressure on managers in these countries. Moreover, for mitigating GW engagement, policymakers should not only develop policies to encourage ethical environmental communication, but also ensure the implementation of these policies.