Long-Term Trends and Characteristics of Water Temperature Extremes of a Large Lowland River During the Summer Season from 1920 to 2023—Case Study of the Bug River in Poland, Eastern Europe

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Standardization of Data Series

2.2. Gaps in the Dataset and the Preprocessing Procedure to Reconstruct Them

2.3. Study Area

2.4. Comparison of Data Across Climate Norm Periods

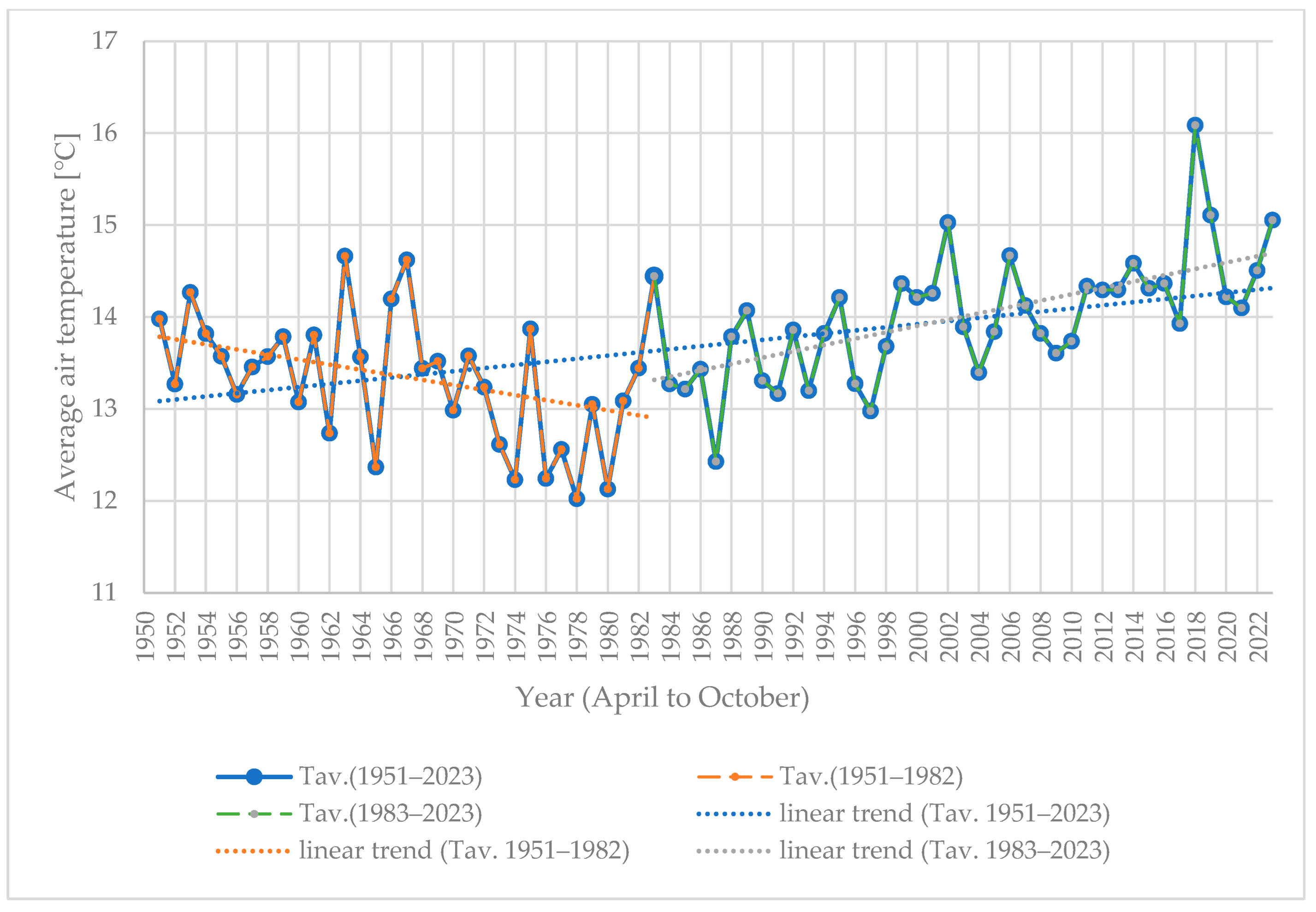

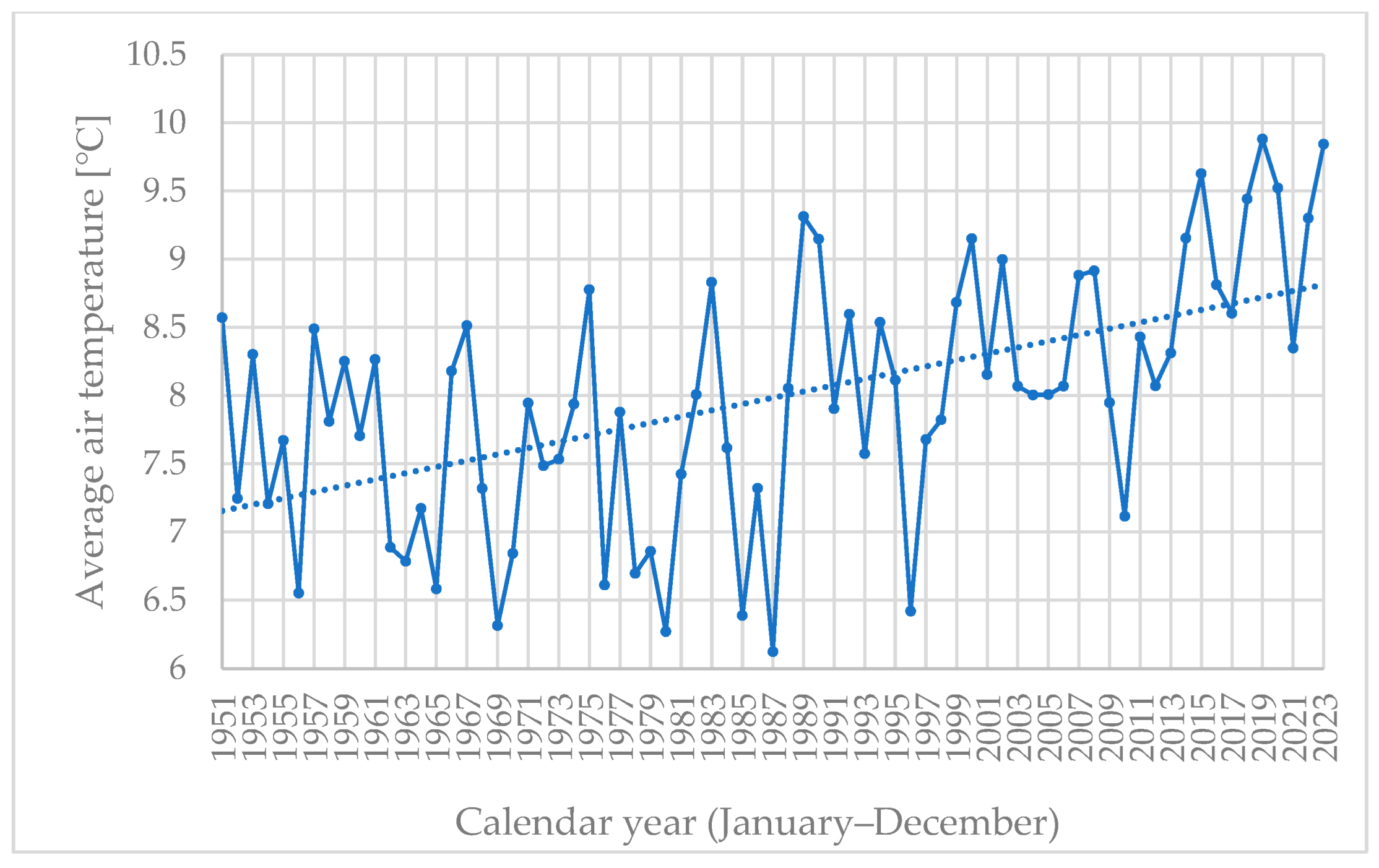

2.5. Meteorological Background

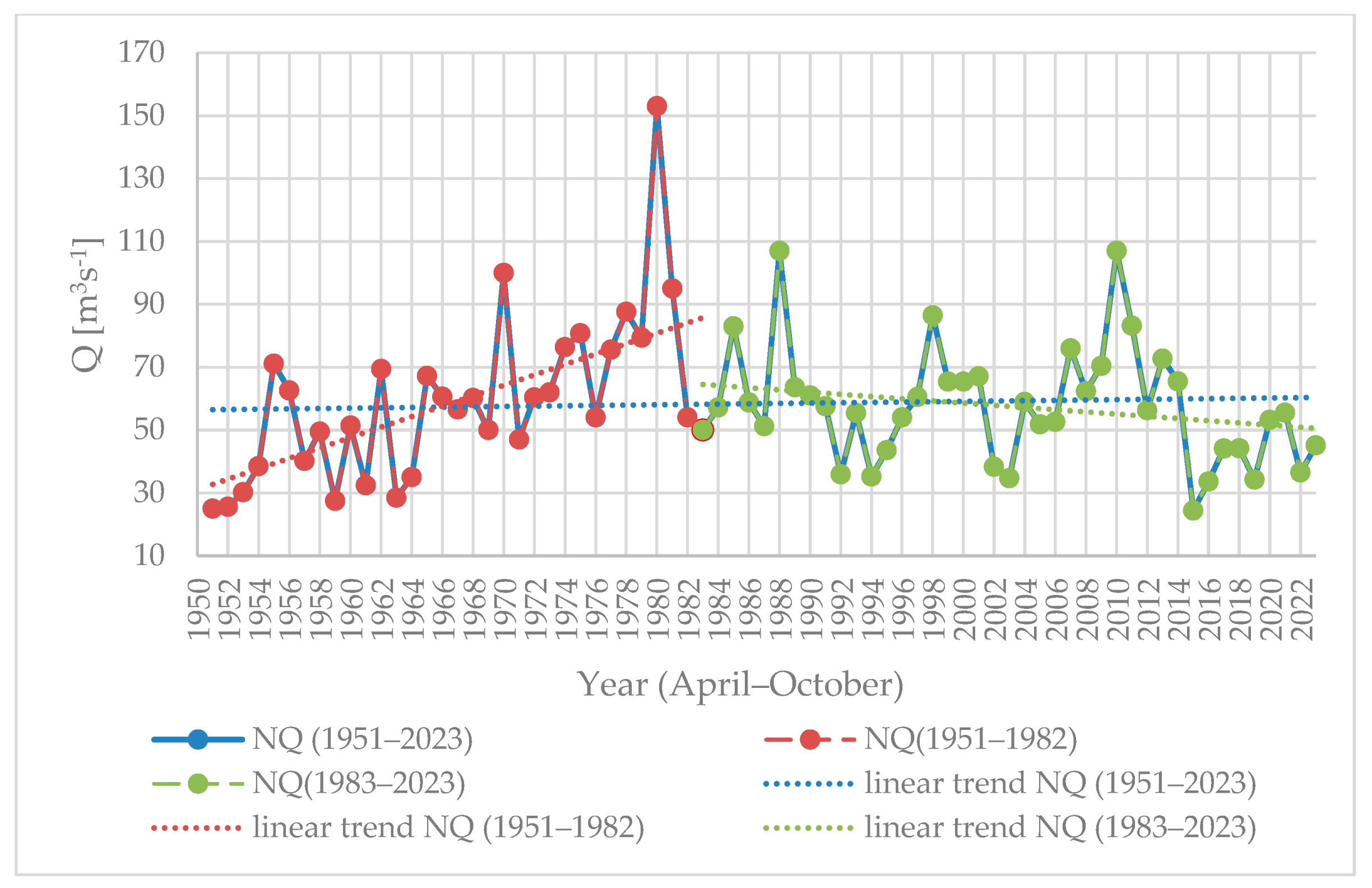

2.6. Hydrological Background

3. Results and Discussion

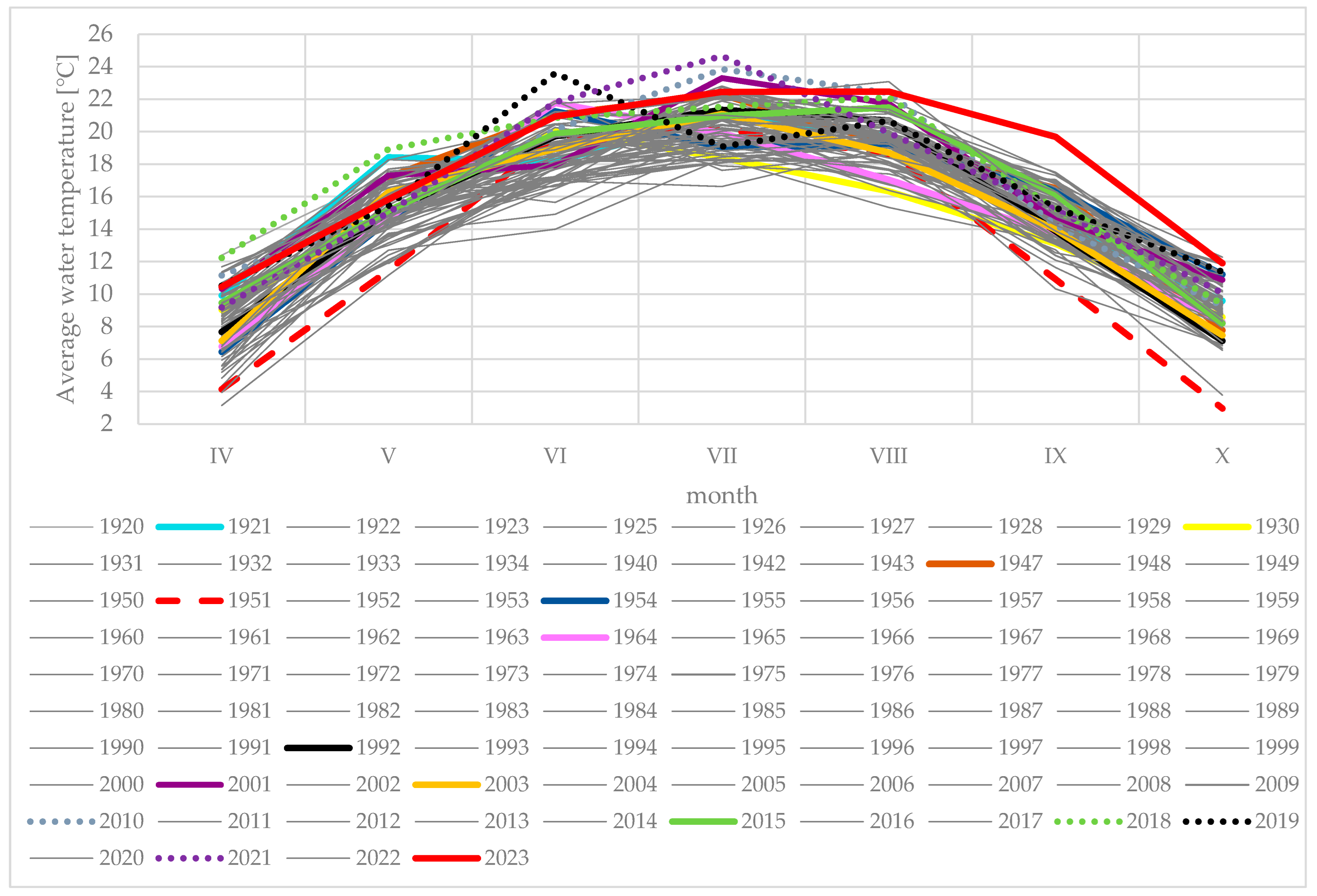

3.1. Characteristics of Average Water Temperature in Relation to the Hydro-Meteorological Conditions

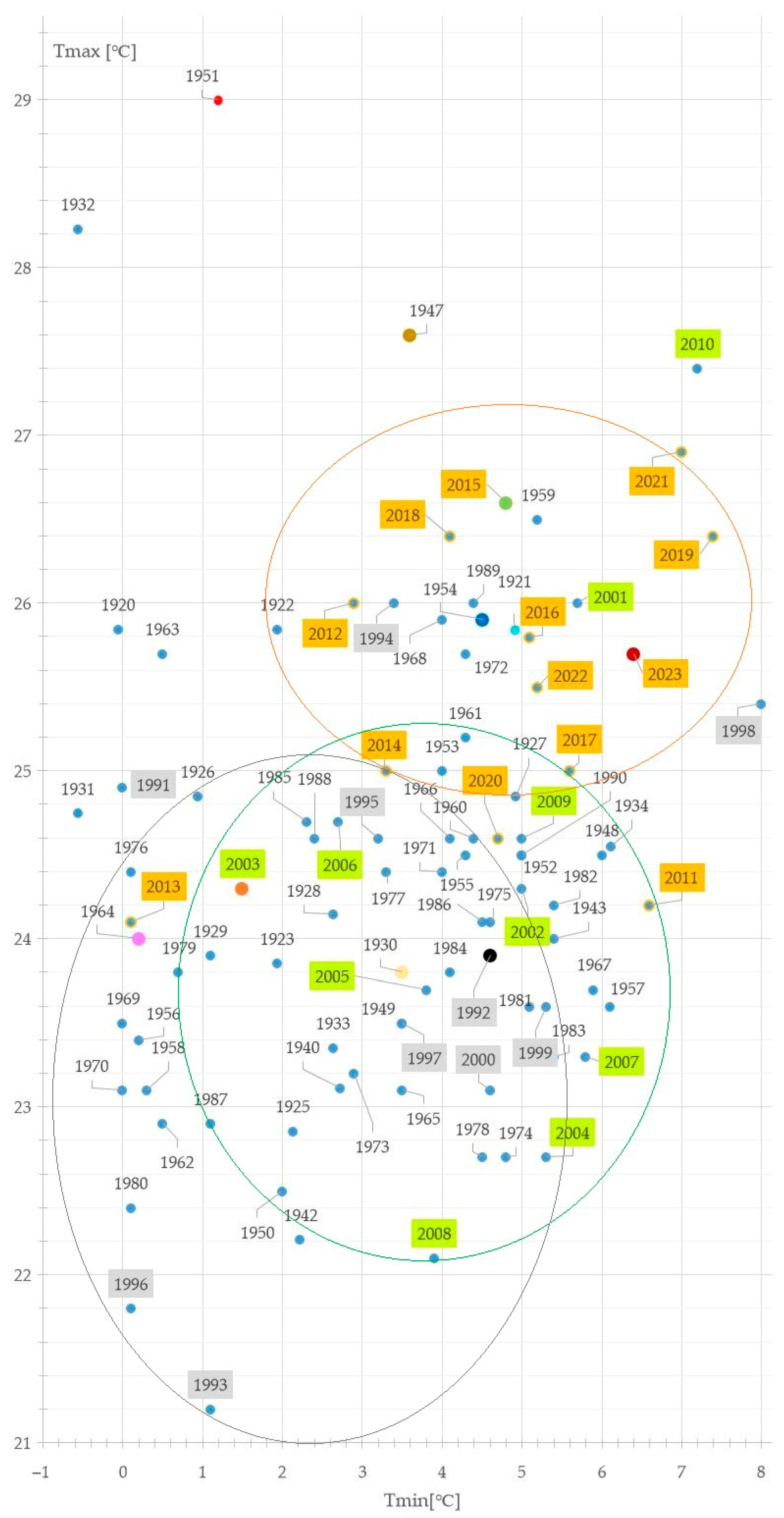

3.2. Characteristics of Maximum, Minimum, and Average Water Temperatures

3.3. Characteristics of Water Temperature in Dry Years and During Streamflow Droughts

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IMGW-PIB | Institute of Meteorology and Water Management—National Research Institute |

| UTC | Coordinated Universal Time |

| NQ | minimum annual discharge |

| H | runoff depth value |

| SNQ | average of the lowest annual discharges |

| BOD | biochemical oxygen demand |

References

- Forster, A. Die Temperatur fliesender Gewasser Mitteleuropas; Geographische Abhandlungen; E.D. Hölzel: Wien, Austria, 1894. [Google Scholar]

- Gołek, J. Termika Rzek Polskich; Prace Państwowego Instytutu Hydrologiczno-Meteorologicznego: Warsaw, Poland, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Instrukcja Dotycząca Pomiarów Temperatury Wody. Wskazówki Dla Obserwatorów Wodowskazowych; Seria A Instrukcje i podręczniki; Wydawnictwa komunikacyjne: Warszawa, Poland, 1952.

- Graf, R.; Wrzesiński, D. Detecting Patterns of Changes in River Water Temperature in Poland. Water 2020, 12, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołek, J.; Meyer, W. Hydrologia; Wydawnictwo Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Kolada, A. Stres Termiczny—Jak Podwyższona Temperatura Wód Zmienia Ekosystemy Wodne. Available online: https://wodnesprawy.pl/stres-termiczny-jak-podwyzszona-temperatura-wod-zmi/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Łaszewski, M.A. The Effect of Environmental Drivers on Summer Spatial Variability of Water Temperature in Polish Lowland Watercourses. Environ. Earth Sci. 2020, 79, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, B.W.; Nobilis, F. Long-Term Changes in River Temperature and the Influence Ofclimatic and Hydrological Factors. Hydrol. Sci. J. Des Sci. Hydrol. 2007, 52, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moatar, F.; Gailhard, J. Water Temperature Behaviour in the River Loire since 1976 and 1881. Comptes Rendus. Géoscience 2006, 338, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.M.; Sharma, S.; Gray, D.K.; Hampton, S.E.; Read, J.S.; Rowley, R.J.; Schneider, P.; Lenters, J.D.; McIntyre, P.B.; Kraemer, B.M.; et al. Rapid and Highly Variable Warming of Lake Surface Waters around the Globe. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 10–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptak, M.; Sojka, M.; Graf, R.; Choiński, A.; Zhu, S.; Nowak, B. Warming Vistula River—The Effects of Climate and Local Conditions on Water Temperature in One of the Largest Rivers in Europe. J. Hydrol. Hydromech. 2022, 70, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenc, H. Wstęp. In Współczesne Problemy Klimatu Polski; Seria Publikacji Naukowo-Badawczych IMGW-PIB; Instytut Meteorologii i Gospodarki Wodnej Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warsaw, Poland, 2019; pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-83-64979-33-0. [Google Scholar]

- Wrzesiński, D. Zmiany Wybranych Cech Reżimu Rzek w Polsce w Warunkach Ocieplenia Klimatu. Acta Geogr. Lodz. 2024, 115, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgromadzenie Ogólne. Rezolucja Przyjęta przez Zgromadzenie Ogólne w Dniu 25 Września 2015 r; Zgromadzenie Ogólne: Krakow, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tomalski, P.; Pius, B.; Jokiel, P.; Marszelewski, W. Changes in the Thermal Regime of Rivers in Poland with Different Sizes and Levels of Human Impact Based on Daily Data (1961–2020). Geogr. Pol. 2025, 98, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokiel, P. Człowiek i Woda. Acta Geogr. Lodz 2024, 115, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaznowska, E.; Wasilewicz, M. Bathing Waters in Poland—Issues of Organization and Supervision of Bathing Areas in the Light of Changes in the Water Law. Acta Sci. Pol. Form. Circumiectus 2019, 18, 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzińska, K.; Szejniuk, B.; Michalska, M.; Berleć, K. Occurrence and Survivability of Escherichia Coli and Enterococci in Waters Used as Bathing Areas. Annu. Set Environ. Prot. Rocz. Ochr. Sr. 2018, 20, 309–325. [Google Scholar]

- Cebula, M.; Ciężak, K.; Mikołajczyk, Ł.; Mikołajczyk, T.; Nowak, M.; Skowronek, D.; Wawręty, R.; Żurek, R. Wybrane Spekty Środowiskowych Skutków Zrzutu Wód Pochłodniczych przez Elektrownie Termiczne z Otwartym Systemem Chłodzenia. In Raport z Badań Terenowych Przeprowadzonych w Latach 2019 i 2020; Stowarzyszenie Pracownia na rzecz Wszystkich Istot: Oświęcim, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kędra, M. Cooling Water for Electricity Production in Poland: Assessment and New Perspectives. Energies 2023, 16, 2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xie, Z.; Liu, B.; Wang, Y.; Gao, J.; Zeng, Y.; Xie, J.; Xie, Z.; Jia, B.; Qin, P.; et al. Global River Water Warming Due to Climate Change and Anthropogenic Heat Emission. Glob. Planet. Change 2020, 193, 103289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznietsov, P.M.; Biedunkova, O.O.; Yaroschuk, O.V.; Pryshchepa, A.M.; Antonyuk, O.O. Analysis of the Impact of Water Use and Consumption for a Nuclear Power Plant on Alterations in the Hydrological and Temperature Regimes of a River: A Case Study. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1415, 012100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, L.H.; Stillwell, A.S. Water Temperature Duration Curves for Thermoelectric Power Plant Mixing Zone Analysis. J. Water Resour. Plann. Manag. 2018, 144, 04018058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmaso, F.; Quadroni, S.; Gentili, G.; Crosa, G. Thermal Regime of a Highly Regulated Italian River (Ticino River) and Implications for Aquatic Communities. J. Limnol. 2016, 76, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducic, V.; Milenkovic, M.; Milijasevic, D.; Vujacic, D.; Bjeljac, Z.; Lovic, S.; Gajic, M.; Andjelkovic, G.; Djordjevic, A. Hiatus in Global Warming—Example of Water Temperature of the Danube River at Bogojevo Gauge (Serbia). Therm. Sci. 2015, 19, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukś, M. Zmienność występowania pokrywy lodowej na rzekach karpackich w świetle wieloletnich serii obserwacyjnych. Współczesne Probl. Gospod. Zasobami Wodnymi 2022, 45, 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ptak, M. Zmiany Temperatury Wody i Zjawisk Lodowych Rzeki Ner (Centralna Polska) w Latach 1965–2014. Pol. J. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 21, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptak, M.; Nowak, B. Zmiany Temperatury Wody w Prośnie w Latach 1965–2014. Woda Sr. Obsz. Wiej. 2017, 17, 101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Brzezińska, W.; Wrzesiński, D. Maximum River Runoff in Poland under Climate Warming Conditions. Quaest. Geogr. 2025, 44, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzezińska, W.; Perz, A.; Wrzesiński, D. Niskie Odpływy Rzek w Polsce w Warunkach Ocieplenia Klimatu. Czas. Geogr. 2025, 96, 455–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaznowska, E.; Wasilewicz, M. Historical streamflow droughts on the Vistula River in Warsaw in the context of the current ones. Acta Sci. Pol. Form. Circumiectus 2020, 19, 53–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kaznowska, E.; Wasilewicz, M.; Hejduk, L.; Krajewski, A.; Hejduk, A. The Groundwater Resources in the Mazovian Lowland in Central Poland during the Dry Decade of 2011–2020. Water 2024, 16, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewski, A.; Sikorska-Senoner, A.E.; Hejduk, L.; Banasik, K. An Attempt to Decompose the Impact of Land Use and Climate Change on Annual Runoff in a Small Agricultural Catchment. Water Resour. Manag. 2021, 35, 881–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somorowska, U. Changes in Drought Conditions in Poland over the Past 60 Years Evaluated by the Standardized Precipitation-Evapotranspiration Index. Acta Geophys. 2016, 64, 2530–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biuletyn IMGW nr 9(276); Biuletyn Państwowej Służby Hydrologiczno-Meteorologicznej. Instytut Meteorologii i Gospodarki Wodnej–Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warszawa, Poland, 2024.

- Baran-Gurgul, K.; Wałęga, A. Seasonal and Regional Patterns of Streamflow Droughts in Poland: A 50-Year Perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerepko, J.; Boczoń, A.; Pierzgalski, E.; Sokołowski, A.W.; Wróbel, M. Habitat Diversity and Spontaneous Succession of Forest Wetlands in Bialowieza Primeval Forest. In Wetlands: Monitoring, Modelling and Management: Proceedings of the International Conference W3M “Wetlands: Modelling, Monitoring, Management”, Wierzba, Poland, 22–25 September 2005; Okruszko, T., Maltby, E., Szatyłowicz, J., Mirosław-Świątek, D., Kotowski, W., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2007; pp. 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Państwowe Gospodarstwo Wodne Wody Polskie. Raport z Przeglądu i Aktualizacji Wstępnej Oceny Ryzyka Powodziowego w 3 Cyklu Planistycznym. Załącznik Nr 7. Powódź We Wrześniu 2024; Państwowe Gospodarstwo Wodne Wody Polskie: Warszawa, Poland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Pomianowski, K.; Rybczyński, M.; Wóycicki, K. Hydrologia Część III. Hydrografia i Hydrometria Wód Powierzchniowych; Komisja wydawnicza Towarzystwa Bratniej Pomocy Studentów Politechniki Warszawskiej: Warszawa, Poland, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Dane Publiczne IMGW. Available online: https://danepubliczne.imgw.pl/data/dane_pomiarowo_obserwacyjne/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Ministerstwo Robót Publicznych. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1920. Spostrzeżenia wodowskazowe. Dorzecze Wisły; Ministerstwo Robót Publicznych: Warszawa, Poland, 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Robót Publicznych. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1921. Spostrzeżenia wodowskazowe. Dorzecze Wisły; Ministerstwo Robót Publicznych: Warszawa, Poland, 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Robót Publicznych. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1922. Dorzecze Wisły; Ministerstwo Robót Publicznych: Warszawa, Poland, 1923. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Robót Publicznych. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1923. Dorzecze Wisły; Ministerstwo Robót Publicznych: Warszawa, Poland, 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Robót Publicznych. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1925. Dorzecze Wisły; Ministerstwo Robót Publicznych: Warszawa, Poland, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Robót Publicznych. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1926. Dorzecze Wisły; Ministerstwo Robót Publicznych: Warszawa, Poland, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Robót Publicznych. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1927. Dorzecze Wisły; Ministerstwo Robót Publicznych: Warszawa, Poland, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Robót Publicznych. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1928. Dorzecze Wisły; Ministerstwo Robót Publicznych: Warszawa, Poland, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Robót Publicznych. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1929. Dorzecze Wisły; Ministerstwo Komunikacji: Warszawa, Poland, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Robót Publicznych. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1930. Dorzecze Wisły; Ministerstwo Komunikacji: Warszawa, Poland, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Robót Publicznych. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1931. Dorzecze Wisły; Ministerstwo Komunikacji: Warszawa, Poland, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Robót Publicznych. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1932. Dorzecze Wisły; Ministerstwo Komunikacji: Warszawa, Poland, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Robót Publicznych. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1933. Dorzecze Wisły; Ministerstwo Komunikacji: Warszawa, Poland, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Robót Publicznych. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1934. Dorzecze Wisły; Ministerstwo Komunikacji: Warszawa, Poland, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1939-1941, Dorzecze Wisły; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1942-1944, Dorzecze Wisły; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1947, Wisła i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły; Wydawnictwa komunikacyjne: Warszawa, Poland, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1948, Wisła i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły; Wydawnictwa komunikacyjne: Warszawa, Poland, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1949, Wisła i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły; Wydawnictwa komunikacyjne: Warszawa, Poland, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1950, Wisła i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły; Wydawnictwa komunikacyjne: Warszawa, Poland, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1951, Wisła i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły; Wydawnictwa komunikacyjne: Warszawa, Poland, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1952, Wisła i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły; Wydawnictwa komunikacyjne: Warszawa, Poland, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1953, Wisła i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły; Wydawnictwa komunikacyjne: Warszawa, Poland, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1954, Wisła i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły; Wydawnictwa komunikacyjne: Warszawa, Poland, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1955, Wisła i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły; Wydawnictwa komunikacyjne: Warszawa, Poland, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1956, Wisła i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1957, Wisła i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1958, Wisła i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1959, Wisła i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrograficzny 1960, Wisła i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrologiczny wód Powierzchniowych, Dorzecze Wisły i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły 1961; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrologiczny wód Powierzchniowych, Dorzecze Wisły i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły 1962; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrologiczny wód Powierzchniowych, Dorzecze Wisły i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły 1963; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrologiczny wód Powierzchniowych, Dorzecze Wisły i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły 1964; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrologiczny wód Powierzchniowych, Dorzecze Wisły i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły 1965; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrologiczny wód Powierzchniowych, Dorzecze Wisły i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły 1966; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrologiczny wód Powierzchniowych, Dorzecze Wisły i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły 1967; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrologiczny wód Powierzchniowych, Dorzecze Wisły i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły 1968; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrologiczny wód Powierzchniowych, Dorzecze Wisły i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły 1969; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrologiczny wód Powierzchniowych, Dorzecze Wisły i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły 1970; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrologiczny wód Powierzchniowych, Dorzecze Wisły i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły 1971; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrologiczny wód Powierzchniowych, Dorzecze Wisły i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły 1972; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrologiczny wód Powierzchniowych, Dorzecze Wisły i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły 1973; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrologiczny wód Powierzchniowych, Dorzecze Wisły i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły 1974; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrologiczny wód Powierzchniowych, Dorzecze Wisły i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły 1975; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrologiczny wód Powierzchniowych, Dorzecze Wisły i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły 1976; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrologiczny wód Powierzchniowych, Dorzecze Wisły i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły 1977; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrologiczny wód Powierzchniowych, Dorzecze Wisły i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły 1978; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrologiczny wód Powierzchniowych, Dorzecze Wisły i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły 1979; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności. Rocznik Hydrologiczny wód Powierzchniowych, Dorzecze Wisły i rzeki Przymorza na wschód od Wisły 1980; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Państwowa Służba Hydrograficzna w Polsce. Instrukcja Dotycząca Pomiarów Temperatury Wód Płynących (Dla Użytku Obserwatorów Stacyj Wodowskazowych) Zatwierdzona Reskryptem Ministerstwa Robót Publicznych z Dnia 30 Czerwca 1927; Państwowa Służba Hydrograficzna w Polsce: Warszawa, Poland, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Wydawnictwa Komunikacyjne. Instrukcja Dotycząca Pomiarów Temperatury Wody. Wskazówki Techniczne Dla Organów Nadzorujących; Seria A Instrukcje i podręczniki; Wydawnictwa komunikacyjne: Warszawa, Poland, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Magnuszewski, A. 60 Lat Jeziora Zegrzyńskiego 1963-2023, Gmina Nieporęt; Urząd Gminy Nieporęt; Dział Informacji Publicznej i Promocji Gminy: Nieporęt, Poland, 2023; ISBN 978-83-962175-2-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ujda, K. (Ed.) Wodowskazy Na Rzekach Polski Cz, I.I. Wodowskazy w Dorzeczu Wisły i Na Rzekach Przymorza Na Wschód Od Wisły; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Fal, B. Czy Niżówki Ostatnich Lat Są Zjawiskiem Wyjątkowym? Gaz. Obs. IMGW 2004, 3, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Farat, R.; Kępińska-Kasprzak, M.; Kowalczyk, P.; Mager, P. Susze Na Obszarze Polski w Latach 1951–1990 [Droughts in Poland in the Years 1951–1990]; Materiały Badawcze IMGW. Gospodarka Wodna i Ochrona Wód; IMGW: Warszawa, Poland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tokarczyk, T. Niżówka Jako Wskaźnik Suszy Hydrologicznej; Monografie Instytutu Meteorologii i Gospodarki Wodnej; Instytut Meteorologii i Gospodarki Wodnej Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warszawa, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hejduk, L.; Kaznowska, E.; Wasilewicz, M.; Hejduk, A. Hydrological Droughts in the Białowieża Primeval Forest, Poland, in the Years 1951–2020. Forests 2021, 12, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowski, W.; Radczuk, L. Nizowka2003 Software. In Hydrological Drought—Processes and Estimation Methods for Streamflow and Groundwater; Tallaksen, L.M., van Lanen, H.A.J., Eds.; Developments in Water Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jarocki, W. Charakterystyczne Stany Wody i Objętości Przepływu w Ważniejszych Przekrojach Wodowskazowych Rzeki Bugu; Prace Państwowego Instytutu Hydrologiczno-Meteorologicznego; Ministerstwo Komunikacji Państwowy Instytut Hydrologiczno-Meteorologiczny: Warszawa, Poland, 1949; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Maksymiuk, A.; Rozbicki, T.; Okruszko, T.; Ignar, S. Wieloletnie tendencje zmian pokrywy śnieżnej i odpływu w wybranych zlewniach północno-wschodniej częsci Polski (Multiyear tendencies changes of snow cover and runoff in selected catchments in the north eastern part of Poland). Rocz. Akad. Rol. W Pozn. 2004, 25, 355–362. [Google Scholar]

- Kaznowska, E. Analysis of Hydrological Drought in the Biebrza River at the Burzyn Gauge 1951-2002. In Wetlands: Monitoring, Modelling and Management: Proceedings of the International Conference w3m “Wetlands: Modelling, Monitoring, Management”, Wierzba, Poland, 22–25 September 2005; Okruszko, T., Maltby, E., Szatyłowicz, J., Mirosław-Świątek, D., Kotowski, W., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2007; pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kępińska-Kasprzyk, M. Zagrożenie wystąpieniem niżówki w Polsce. Hydrol. W Inżynierii I Gospod. Wodnej 2014, 1, 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- Marsz, A.; Styszyńska, A. Skala i Przyczyny Zmian Temperatury Najcieplejszych Miesięcy Roku Nad Obszarem Polski Po Roku 1988 (The Scale and Causes of Changes in the Temperature of the Warmest Months of the Year over the Area of Poland after 1988). In Współczesne Problemy Klimatu Polski; Chojnacka-Ożga, L., Lorenc, H., Eds.; Seria Publikacji Naukowo-Badawczych IMGW-PIB; Instytut Meteorologii i Gospodarki Wodnej Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warszawa, Poland, 2019; pp. 9–26. ISBN 978-83-64979-33-0. [Google Scholar]

- Gutowska-Siwiec, L. Wprowadzenie do części II. In Zrównoważone Gospodarowanie Zasobami Wodnymi Oraz Infrastrukturą Hydrotechniczną w Świetle Prognozowanych Zmian Klimatycznych; Majewski, W., Walczykiewicz, T., Eds.; Seria Publikacji Naukowo-Badawczych IMGW-PIB; Instytut Meteorologii i Gospodarki Wodnej Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warszawa, Poland, 2012; pp. 107–108. ISBN 978-83-61102-68-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ślesicki, M. Wplyw zmian klimatycznych na wybrane wskaźniki jakości wód powierzchniowych. In Zrównoważone Gospodarowanie Zasobami Wodnymi Oraz Infrastrukturą Hydrotechniczną w Świetle Prognozowanych Zmian Klimatycznych; Majewski, W., Walczykiewicz, T., Eds.; Seria Publikacji Naukowo-Badawczych IMGW-PIB; Instytut Meteorologii i Gospodarki Wodnej Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warszawa, Poland, 2012; pp. 107–108. ISBN 978-83-61102-68-7. [Google Scholar]

- Biuletyn Państwowej Służby Hydrologiczno-Meteorologicznej. Biuletyn Państwowej Służby Hydrologiczno-Meteorologicznej Rok 2023; Biuletyn nr 13 (267); Państwowa Służba Hydrologiczno-Meteorologiczna: Warszawa, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Biuletyn Państwowej Służby Hydrologiczno-Meteorologicznej. Biuletyn IMGW nr 9(289). Biuletyn Państwowej Służby Hydrologiczno-Meteorologicznej: Warszawa, Poland, 2025.

- Maciejewski, M. Od Autora projektu. In Zrównoważone Gospodarowanie Zasobami Wodnymi Oraz Infrastrukturą Hydrotechniczną w Świetle Prognozowanych Zmian Klimatycznych; Majewski, W., Walczykiewicz, T., Eds.; Seria Publikacji Naukowo-Badawczych IMGW-PIB; Instytut Meteorologii i Gospodarki Wodnej Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warszawa, Poland, 2012; pp. 107–108. ISBN 978-83-61102-68-7. [Google Scholar]

| Zegrze Gauging Station | Wyszków Gauging Station | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Observation Period | Time of Measurement | Observation Period | Time of Measurement |

| 1920–1923 1925–1926 1927 1928–1930 1931–1932 1933–1934 1940 1942 1943 | 7 a.m. local time *1 7 a.m. local time *1 January and February—8 a.m. local time From March to September—6 a.m. local time From October to December—11 a.m. local time 11 a.m. local time 11 a.m. local time *2 11 a.m. local time 11 a.m. local time No information *3 11 a.m. local time | 1928 1929–1930 1941 1942–1943 1947–1983 1984–2000 2000–2023 | August—6 a.m. local time Other months—12. a.m. local time *4 12 a.m. No information *5 7 a.m. local time 7 a.m. local time 7 a.m. local time 6 UTC (at 8 a.m. summertime in Poland, at 7 a.m. wintertime in Poland) |

| Months | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | X |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowland rivers | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| Year | Regression Equation y = ax + b y—Wyszków Profile x—Zegrze Profile | R2 | p-Value | RSE | F-Statistic (df1, df2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1920–1923; 1925–1927; 1928 *1 1931–1934 | y = 0.9962x − 0.0551 | 0.96 | <0.001 | 0.898 | 5624 (1.212) |

| 1940; 1942–1943 *2 | y = 0.8607x + 2.7251 | 0.91 | <0.001 | 1.183 | 1546 (1.151) |

| Period | Dry Years with the Hydrological Streamflow Drought of Surface Water |

|---|---|

| 1901–2000 | 1901 1904 1911 1913 1920 1921 1925 1928 1929 1930 1934 1943 1947 1948 1949 1950 1951 1952 1953 1954 1959 1961 1963 1964 1969 1970 1983 1985 1989 1990 1992 1993 1994 2000 |

| 2001–2025 | 2002 2003 2005 2006 2008 2012 2015 2016 2019 2020 2022 2023 2025 |

| Month | Basic Statistics | Climate Norm Period | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1961–1990 | 1971–2000 | 1981–2010 | 1991–2020 | ||

| April | Minimum | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Average | 8.2 | 8.1 | 8.6 | 9.1 | |

| Maximum | 18.6 | 18.1 | 18.1 | 18.4 | |

| Mai | Minimum | 6.4 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 5.1 |

| Average | 15.1 | 15.3 | 15.5 | 15.7 | |

| Maximum | 22.8 | 22.8 | 23.2 | 23.3 | |

| June | Minimum | 9.5 | 11.2 | 11.2 | 11.2 |

| Average | 18.8 | 18.8 | 18.7 | 19.4 | |

| Maximum | 25.9 | 25.4 | 25.4 | 26.4 | |

| July | Minimum | 14.3 | 14.0 | 14.0 | 14.0 |

| Average | 19.8 | 20.1 | 20.7 | 21.0 | |

| Maximum | 26.0 | 26.0 | 27.4 | 27.4 | |

| August | Minimum | 12.4 | 12.4 | 12.7 | 12.8 |

| Average | 18.9 | 19.5 | 19.9 | 20.4 | |

| Maximum | 25.5 | 26.0 | 26.0 | 26.6 | |

| September | Minimum | 8.1 | 8.1 | 8.6 | 8.6 |

| Average | 14.4 | 14.5 | 14.7 | 15.3 | |

| Maximum | 21.7 | 22.3 | 22.3 | 22.8 | |

| October | Minimum | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Average | 8.9 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 9.7 | |

| Maximum | 16.2 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | |

| April–October Value | According to Gołek [2] | Climate Norm Period | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1948–1956 | 1961–1990 | 1971–2000 | 1981–2010 | 1991–2020 | ||

| Tmin IV–X | [°C] | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Tmax IV–X | 29.0 | 26.0 | 26.0 | 27.4 | 27.4 | |

| Tav. IV–X | 14.5 | 14.9 | 15.0 | 15.4 | 15.8 | |

| Tav.,min IV–X | 2.8 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 4.0 | 4.1 | |

| Tav.maxIV–X | 24.8 | 24.0 | 23.9 | 24.1 | 24.5 | |

| ΔTav.,max IV–X –Tav.min IV–X) | 22.0 | 20.9 | 20.5 | 20.1 | 20.4 | |

| Month | Basic Statistics | Dry Years from 1920 to 2023 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1921 | 1930 | 1947 | 1954 | 1964 | 1983 | 1992 | 2003 | 2015 | 2020 | 2023 | ||

| April | Minimum | 6.9 | 3.5 | - | 4.5 | 0.2 | 6.7 | 5.3 | 2.7 | 5.4 | 4.7 | 6.4 |

| Average | 9.9 | 9.0 | - | 6.4 | 6.8 | 10.1 | 7.7 | 7.1 | 9.5 | 9.5 | 10.5 | |

| Maximum | 16.9 | 13.9 | - | 9.5 | 14.3 | 16.0 | 12.3 | 13.0 | 15.2 | 13.6 | 14.4 | |

| Mai | Minimum | 12.9 | 12.8 | 9.0 | 10.7 | 11.1 | 12.8 | 11.3 | 13.6 | 13.3 | 10.8 | 12.3 |

| Average | 18.4 | 14.8 | 17.2 | 14.5 | 14.7 | 17.5 | 15.1 | 16.3 | 15.1 | 14.2 | 15.8 | |

| Maximum | 21.9 | 18.2 | 21.6 | 20.3 | 20.5 | 22.8 | 19.7 | 20.7 | 17.6 | 17.4 | 19.6 | |

| June | Minimum | 11.9 | 16.4 | 16.7 | 17.5 | 19.7 | 16.7 | 15.9 | 16.6 | 17.0 | 15.0 | 18.5 |

| Average | 18.2 | 20.1 | 21.1 | 21.3 | 21.8 | 19.0 | 19.7 | 19.0 | 19.9 | 21.1 | 20.9 | |

| Maximum | 25.8 | 23.8 | 27.1 | 25.9 | 24.0 | 21.6 | 22.5 | 21.5 | 22.8 | 24.6 | 23.8 | |

| July | Minimum | 15.9 | 14.9 | 17.0 | 16.0 | 15.0 | 16.8 | 19.1 | 17.8 | 16.4 | 19.6 | 20.1 |

| Average | 20.9 | 18.4 | 22.3 | 19.1 | 19.9 | 20.8 | 21.3 | 21.1 | 21.0 | 22.0 | 22.4 | |

| Maximum | 25.8 | 22.2 | 27.6 | 22.3 | 23.4 | 23.3 | 23.9 | 24.3 | 24.8 | 24.2 | 24.7 | |

| August | Minimum | 16.9 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 16.6 | 14.6 | 17.2 | 18.1 | 12.8 | 17.5 | 18.5 | 18.8 |

| Average | 19.7 | 16.3 | 19.2 | 19.2 | 17.0 | 19.7 | 20.7 | 18.7 | 21.5 | 21.4 | 22.5 | |

| Maximum | 24.8 | 20.6 | 22.1 | 22.7 | 20.7 | 22.0 | 23.9 | 23.5 | 26.6 | 24.5 | 25.7 | |

| September | Minimum | 10.9 | 11.7 | 12.7 | 10.2 | 10.0 | 10.8 | 11.9 | 11.5 | 12.9 | 14.0 | 17.4 |

| Average | 14.4 | 13.1 | 16.5 | 16.4 | 13.7 | 15.3 | 13.9 | 14.0 | 16.1 | 16.8 | 19.7 | |

| Maximum | 16.9 | 15.5 | 20.8 | 21.2 | 18.3 | 19.4 | 22.3 | 16.3 | 22.8 | 19.0 | 22.0 | |

| October | Minimum | 4.9 | 7.6 | 3.6 | 7.2 | 3.2 | 5.4 | 4.6 | 1.5 | 4.8 | 8.9 | 8.5 |

| Average | 9.6 | 8.6 | 7.8 | 11.2 | 8.3 | 8.8 | 7.1 | 7.5 | 8.2 | 12.3 | 11.9 | |

| Maximum | 11.9 | 12.8 | 11.0 | 15.1 | 11.8 | 12.8 | 12.1 | 13.0 | 13.6 | 15.4 | 16.6 | |

| No. | Date dd.mm.yyyy | Characteristics of Streamflow Droughts | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tn | Vn | Vav.,n | Qav.,n | Qmin,n | Date of Qmin,n | ||

| days | th.m3 | th.m3 | m3s−1 | m3s−1 | dd.mm.yyyy | ||

| 1 | 02.08–23.11.1921 | 113 | - | - | - | 35.0 *1 | 13.11.1921 |

| 2 | 02.07–10.08.1930 | 40 | - | - | - | 40.0 *2 | 09.07.1930 |

| 3 | 29.05–20.11.1947 | 176 | - | - | - | 30.0 *3 | 19–22.08.1947 |

| 4 | 05.07–08.11.1954 | 118 | 73,768 | 586 | 45.4 | 38.5 | 25.09.1954 |

| 5 | 20.06–15.11.1964 | 149 | 104,337 | 700 | 44.1 | 35.0 | 26.07.1964 |

| 6 | 30.07–08.09.1992 | 41 | 42,733 | 1042 | 40.1 | 35.9 | 23.08.1992 |

| 7 | 10.07–22.10.2003 | 105 | 91,074 | 867 | 42.2 | 34.7 | 27.08.2003 |

| 8 | 06.07–21.10.2015 | 108 | 144,357 | 1337 | 36.7 | 24.4 | 03.09.2015 |

| 9 | 29.08–21.10.2023 | 54 | 16,874 | 312 | 48.7 | 45.1 | 29.09.2023 |

| No. | Date dd.mm.yyyy | Characteristics of Water Temperature During Streamflow Droughts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tav.n | Tmax,n | Tmin,n | Date of Tmax,n | Date of Tmin,n | ||

| °C | °C | °C | dd.mm.yyyy | dd.mm.yyyy | ||

| 1 | 02.08–23.11.1921 * | 14.5 | 24.8 | 4.9 | 03–04.08.1921 | 31.10.1921 |

| 2 | 02.07–10.08.1930 | 18.2 | 21.5 | 14.9 | 02–05.07.1930 | 09–11.07.1930 |

| 3 | 29.05–20.11.1947 * | 17.4 | 27.6 | 3.6 | 01.07.1947 | 25.10.1947 |

| 4 | 05.07–08.11.1954 * | 16.3 | 22.7 | 7.2 | 06.08.1954 | 28.10.1954 |

| 5 | 20.06–15.11.1964 * | 15.4 | 23.5 | 3.2 | 21.06.1964 | 31.10.1964 |

| 6 | 30.07–08.09.1992 | 19.6 | 23.9 | 11.9 | 11.08.1992 | 07.09.1992 |

| 7 | 10.07–22.10.2003 | 16.1 | 24.3 | 4.6 | 29–30.07.2003 | 22.10.2003 |

| 8 | 06.07–21.10.2015 | 17.3 | 26.6 | 4.8 | 09.09.2015 | 13.10.2015 |

| 9 | 29.08–21.10.2023 | 17.0 | 23.4 | 8.5 | 29.08.2023 | 19–20.10.2023 |

| y = ax + b y—Tmax,n; x—Parameters of Streamflow Droughts | Parameters of Streamflow Droughts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qav.n | Qmin,n | Vn | Vav.n | |

| m3s−1 | m3s−1 | th.m3 | th.m3 | |

| n | 6 | 9 | 6 | 6 |

| R2 | 0.68 | 0.62 | 0.46 | 0.69 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaznowska, E.; Wasilewicz, M.; Hejduk, A.; Stelmaszczyk, M.; Hejduk, L. Long-Term Trends and Characteristics of Water Temperature Extremes of a Large Lowland River During the Summer Season from 1920 to 2023—Case Study of the Bug River in Poland, Eastern Europe. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11189. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411189

Kaznowska E, Wasilewicz M, Hejduk A, Stelmaszczyk M, Hejduk L. Long-Term Trends and Characteristics of Water Temperature Extremes of a Large Lowland River During the Summer Season from 1920 to 2023—Case Study of the Bug River in Poland, Eastern Europe. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11189. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411189

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaznowska, Ewa, Michał Wasilewicz, Agnieszka Hejduk, Mateusz Stelmaszczyk, and Leszek Hejduk. 2025. "Long-Term Trends and Characteristics of Water Temperature Extremes of a Large Lowland River During the Summer Season from 1920 to 2023—Case Study of the Bug River in Poland, Eastern Europe" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11189. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411189

APA StyleKaznowska, E., Wasilewicz, M., Hejduk, A., Stelmaszczyk, M., & Hejduk, L. (2025). Long-Term Trends and Characteristics of Water Temperature Extremes of a Large Lowland River During the Summer Season from 1920 to 2023—Case Study of the Bug River in Poland, Eastern Europe. Sustainability, 17(24), 11189. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411189