Temporo-Spatial Relationship Between Energy Consumption, Air Pollution and Carbon Emissions in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area and Dataset

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Dataset

- Annual mean concentrations of PM2.5 during 2000–2020 at 1 km spatial resolution;

- Annual mean concentrations of SO2 during 2013–2020 at 10 km spatial resolution;

- Annual mean concentrations of NO2 during 2008–2020 at 10 km spatial resolution.

3. Methods

3.1. Data Preprocessing for Spatial Analysis

3.2. Spatial Correlation Matrices

- A coefficient approaching +1 indicates a strong positive correlation, reflecting similar spatial distribution patterns between variables;

- A coefficient approaching −1 indicates a strong negative correlation, manifesting as divergent spatial distribution patterns between variables.

3.3. Decoupling Analysis

- and represent the base period and end period, respectively;

- denotes the decoupling index between atmospheric environmental indicators and energy consumption at the end period relative to the base period;

- is the change in atmospheric environmental indicators;

- is the change in energy consumption;

- represents the values of atmospheric environmental indicators;

- denotes energy consumption values.

- Strong Decoupling: Represents an optimal scenario where increased energy consumption coexists with reduced atmospheric pollution/carbon emissions;

- Weak Decoupling: Denotes partial decoupling, characterized by energy consumption growth outpacing the growth rate of atmospheric pollution/carbon emissions;

- Recessive Decoupling: Occurs when reductions in atmospheric pollution/carbon emissions exceed the rate of energy consumption decline;

- Strong Negative Decoupling: An undesirable state where energy consumption decreases but atmospheric pollution/carbon emissions increase;

- Weak Negative Decoupling: Reflects concurrent reductions in both energy consumption and atmospheric pollution/carbon emissions, though with smaller environmental improvement relative to energy reduction;

- Expansive Negative Decoupling: Represents both energy consumption and atmospheric pollution/carbon emissions increase, though with environmental degradation outpacing energy demand growth.

4. Results

4.1. Spatial Correlation Analysis

4.2. Time Series Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Spatiotemporal Decoupling Characteristics and Evolution of Energy Consumption and Atmospheric Environment

- (1)

- 2000–2008: During this initial phase, the GBA cities initiated their air pollution control measures in response to growing environmental concerns. PM2.5 exhibited predominantly weak decoupling from energy consumption, reflecting early-stage mitigation efforts. However, the situation regarding carbon emission control remains suboptimal, as the relationship between CO2 emissions and energy consumption in most cities exhibits an expansive negative decoupling, indicating that the GBA still requires strengthened efforts in carbon emission management.

- (2)

- 2008–2013: Marked by intensified environmental policies, this period saw improved air quality outcomes. While PM2.5 maintained weak decoupling patterns, some cities achieved strong decoupling as concentrations began declining. NO2 demonstrated emerging weak decoupling from energy consumption, signaling progress in vehicular emission controls. However, although the GBA also shows a positive trend in carbon emission control, the progress is relatively slow and further efforts are still needed.

- (3)

- 2013–2020: Representing a watershed period, the GBA achieved strong decoupling for all three air pollutants relative to energy consumption, reflecting comprehensive air quality improvements. Notably, carbon emissions entered a declining phase, with the relationship between carbon emissions and energy consumption transitioning from a phase of expansive negative decoupling to one characterized predominantly by weak decoupling in most cities, demonstrating the effectiveness of integrated climate policies.

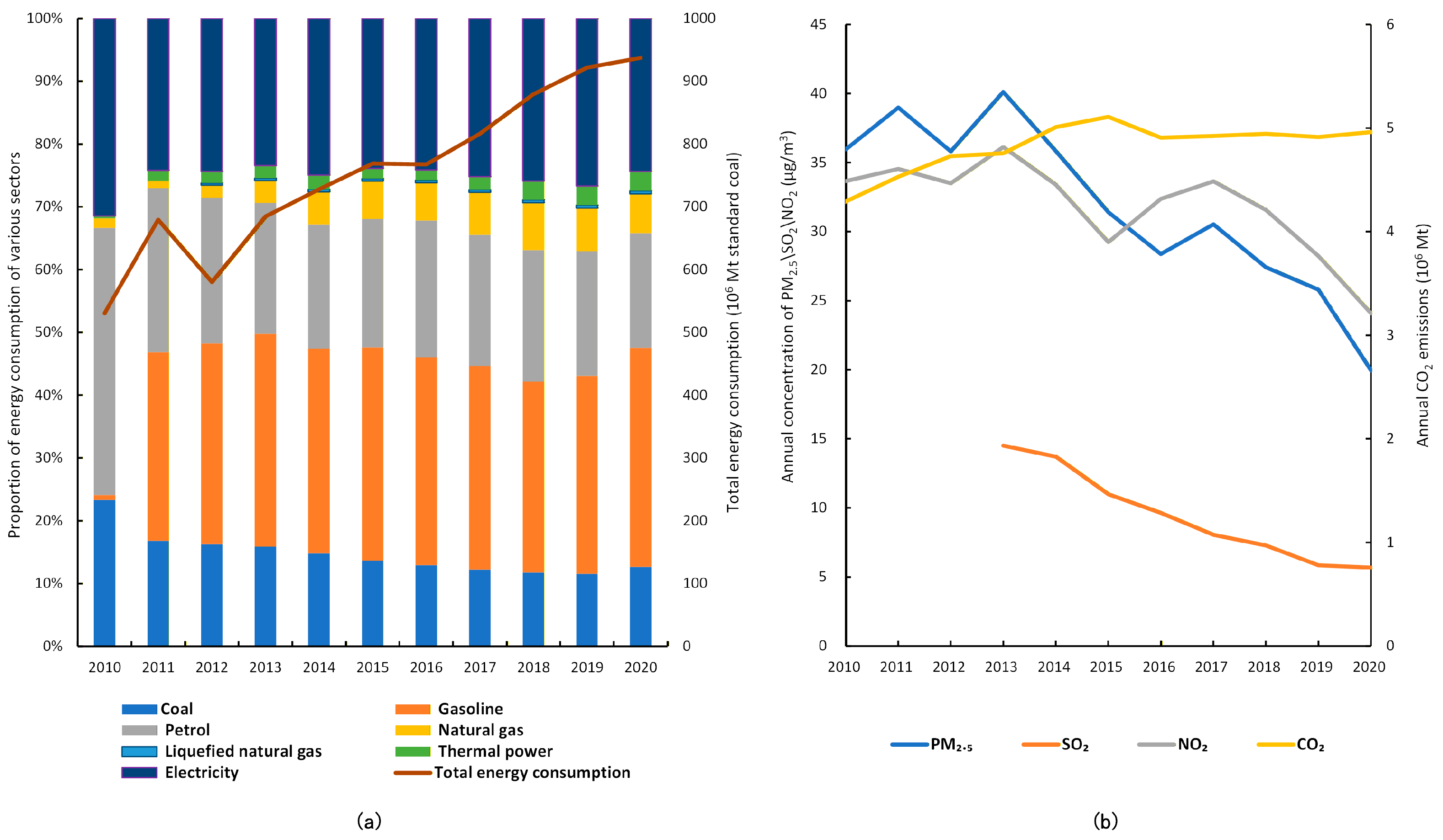

5.2. Energy Structure–Atmospheric Environment Relationship Based on a Representative City (Zhuhai)

5.3. Implications, Research Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, T.; Song, Q.; Qi, Y. An integrated approach to evaluating the coupling coordination degree between low-carbon development and air quality in Chinese cities. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2021, 12, 710–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Duan, Z.; Wei, T.; Pan, H. Spatial disparities and sources analysis of co-benefits between air pollution and carbon reduction in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 354, 120433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhu, L. Does renewable energy technological innovation control China’s air pollution? A spatial analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 250, 119515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, K.; Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Tang, L. Industrial activity, energy structure, and environmental pollution in China. Energy Econ. 2021, 104, 105633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, Z.; Mao, X.; Cai, B.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Gao, Y.; Guo, Z. Exploring the spatiotemporal pattern evolution of carbon emissions and air pollution in Chinese cities. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jia, X. Analysis of energy consumption structure on CO2 emission and economic sustainable growth. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 1667–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, B.W.; Zhang, F.Q. A survey of index decomposition analysis in energy and environmental studies. Energy 2000, 25, 1149–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dritsaki, C.; Dritsaki, M. Causal relationship between energy consumption, economic growth and CO2 emissions: A dynamic panel data approach. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2014, 4, 125–136. [Google Scholar]

- Mirza, F.M.; Kanwal, A. Energy consumption, carbon emissions and economic growth in Pakistan: Dynamic causality analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 72, 1233–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; He, S.; Zhou, H. Spatio-temporal characteristics and convergence trends of PM2.5 pollution: A case study of cities of air pollution transmission channel in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Tao, F.; Zhang, S.; Lin, S.; Zhou, T. Spatiotemporal distribution characteristics and driving forces of PM2.5 in three urban agglomerations of the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, L. Study on spatiotemporal distribution of the tropospheric NO2 column concentration in China and its relationship to energy consumption based on the time-series data from 2005 to 2013. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2020, 42, 2130–2144. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Y.; Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, L.; Chen, S. Spatiotemporal trajectory of energy efficiency in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area and implications on the route of economic transformation. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, X.; Webster, C. Spatio-temporal impact of land use changes on nitrogen emissions in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area. J. Ind. Ecol. 2025, 29, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wu, J.; Su, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wu, X.; Wen, X.; Huang, G.; Deng, Y.; Raffaele, L.; Chen, X. Estimating ecological sustainability in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area, China: Retrospective analysis and prospective trajectories. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 303, 114167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, H.; Kou, J.; Shao, Q. Evaluation of urban comprehensive carrying capacity in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area based on regional collaboration. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 20025–20036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, D. The Power Transition under the Interaction of Different Systems—A Case Study of the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Zhou, B. Sustainable future: A systematic review of city-region development in bay areas. Front. Sustain. Cities 2023, 5, 1052568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yu, B.; Yang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Yao, S.; Qian, X.; Wang, C.; Wu, B.; Wu, J. An Extended Time Series (2000–2018) of Global NPP-VIIRS-Like Nighttime Light Data from a Cross-Sensor Calibration. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 889–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.Q.; Wang, J.L.; Yang, F. Research progress in spatialization of population data. Prog. Geogr. 2013, 32, 1692–1702. [Google Scholar]

- Bright, E.; Coleman, P.; Dobson, J.E. LandScan: A global population database for estimating populations at risk. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2000, 66, 849–857. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Y.; Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X. Grid model of Energy consumption using random forest by integrating data of nighttime light, population and urban impervious surface (2000–2020) in Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macau Greater Bay Area. Energies 2024, 17, 2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Li, Z.; Lyapustin, A.; Sun, L.; Peng, Y.; Xue, W.; Su, T.; Cribb, M. Reconstructing 1-km-resolution high-quality PM2. 5 data records from 2000 to 2018 in China: Spatiotemporal variations and policy implications. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 252, 112136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Gupta, P.; Cribb, M. Ground-level gaseous pollutants (NO2, SO2, and CO) in China: Daily seamless mapping and spatiotemporal variations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 1511–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, T.; Maksyutov, S.; Andres, R.J. The Open-source Data Inventory for Anthropogenic CO2, version 2016 (ODIAC2016): A global monthly fossil fuel CO2 gridded emissions data product for tracer transport simulations and surface flux inversions. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2018, 10, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z. Analysis on spatial distribution of air pollution and its spatial correlation with influencing factors in Xiamen City. Chin. J. Environ. Eng. 2014, 8, 5406–5412. [Google Scholar]

- Tapio, P. Towards a theory of decoupling: Degrees of decoupling in the EU and the case of road traffic in Finland between 1970 and 2001. Transp. Policy 2005, 12, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Kong, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhou, H. Spatiotemporal pattern and convergence test of energy eco-efficiency in the Yellow River Basin. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Chang, S.; Yang, Z.; Luo, Y.; Liao, C. An integrated air quality improvement path of energy-environment policies in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J.; Liu, T.; Du, C.D.; Hu, R.; Wu, X. From research to policy recommendations: A scientometric case study of air quality management in the Greater Bay Area, China. Environ. Sci. Policy 2025, 165, 104025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conibear, L.; Reddington, C.L.; Silver, B.J.; Knote, C.; Arnold, S.R.; Spracklen, D.V. Regional policies targeting residential solid fuel and agricultural emissions can improve air quality and public health in the Greater Bay Area and across China. GeoHealth 2021, 5, e2020GH000341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, A.M. Energy, environment and sustainable development. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2008, 12, 2265–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wei, T.; Chen, S.; Wang, S.; Qiu, R. Pathways to a more efficient and cleaner energy system in Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area: A system-based simulation during 2015–2035. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 174, 105835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zantye, M.S.; Arora, A.; Hasan, M.F. Renewable-integrated flexible carbon capture: A synergistic path forward to clean energy future. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 3986–4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, K.; Liang, S.; Zeng, X.; Cai, Y.; Meng, J.; Shan, Y.; Guan, D.; Yang, Z. Trends, drivers, and mitigation of CO2 emissions in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area. Engineering 2023, 23, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data | Unit | Spatial Resolution | Year | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual energy consumption | 106 Mt of standard coal | 500 m | 2000–2020 | Annual energy consumption at the city level retrieved from nighttime light data [19], population data [20], and urban impervious surface data [21] using a random forest model [22] |

| PM2.5 Concentrations | µg/m3 | 1 km | 2000–2020 | The high-resolution and high-quality near-surface air pollutant database (CHAP) (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn (accessed on 25 September 2023) |

| SO2 Concentrations | µg/m3 | 10 km | 2013–2020 | The high-resolution and high-quality near-surface air pollutant database (CHAP) (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn (accessed on 15 October 2023) |

| NO2 Concentrations | µg/m3 | 10 km | 2008–2020 | The high-resolution and high-quality near-surface air pollutant database (CHAP) (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn (accessed on 22 October 2023) |

| CO2 Concentrations | kg/m2/s | 0.1° | 2000–2020 | Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR) (https://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 26 October 2023) |

| Annual energy consumption structure of Zhuhai City | 106 Mt of standard coal | - | 2010–2020 | Zhuhai Statistical Yearbooks |

| Decoupling Status | Decoupling Types | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decoupling | Strong Decoupling | ≤0 | >0 | ≤ 0 |

| Weak Decoupling | >0 | >0 | < 1 | |

| Recessive Decoupling | <0 | <0 | ≥ 1 | |

| Negative Decoupling | Strong Negative Decoupling | ≥0 | <0 | ≤ 0 |

| Weak Negative Decoupling | <0 | <0 | < 1 | |

| Expansive Negative Decoupling | >0 | >0 | ≥ 1 |

| Year | Spatial Correlation Coefficient | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM2.5 | SO2 | NO2 | CO2 | |

| 2000 | 0.2515 | \ | \ | 0.4729 |

| 2001 | 0.3156 | \ | \ | 0.5829 |

| 2002 | 0.2521 | \ | \ | 0.5676 |

| 2003 | 0.3318 | \ | \ | 0.5588 |

| 2004 | 0.3485 | \ | \ | 0.5690 |

| 2005 | 0.3251 | \ | \ | 0.5267 |

| 2006 | 0.3492 | \ | \ | 0.4970 |

| 2007 | 0.2855 | \ | \ | 0.4436 |

| 2008 | 0.3578 | \ | 0.6975 | 0.4618 |

| 2009 | 0.2387 | \ | 0.7023 | 0.4646 |

| 2010 | 0.2982 | \ | 0.6500 | 0.4186 |

| 2011 | 0.3393 | \ | 0.7053 | 0.4218 |

| 2012 | 0.3000 | \ | 0.6465 | 0.4075 |

| 2013 | 0.3512 | −0.1621 | 0.7568 | 0.4063 |

| 2014 | 0.2035 | −0.2574 | 0.7373 | 0.4036 |

| 2015 | 0.2920 | −0.2428 | 0.7661 | 0.4084 |

| 2016 | 0.2892 | −0.1341 | 0.7639 | 0.4028 |

| 2017 | 0.2112 | −0.0943 | 0.7157 | 0.3800 |

| 2018 | 0.2846 | −0.2547 | 0.7219 | 0.3657 |

| 2019 | 0.3434 | −0.3815 | 0.7617 | 0.3734 |

| 2020 | 0.2116 | −0.3814 | 0.7571 | 0.3808 |

| Average level | 0.2943 | −0.2385 | 0.7217 | 0.4388 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, C.; Lei, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, J. Temporo-Spatial Relationship Between Energy Consumption, Air Pollution and Carbon Emissions in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11175. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411175

Xu C, Lei Y, Liu X, Wang Y, Xiao J. Temporo-Spatial Relationship Between Energy Consumption, Air Pollution and Carbon Emissions in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area, China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11175. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411175

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Chao, Yanfei Lei, Xulong Liu, Yunpeng Wang, and Jie Xiao. 2025. "Temporo-Spatial Relationship Between Energy Consumption, Air Pollution and Carbon Emissions in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area, China" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11175. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411175

APA StyleXu, C., Lei, Y., Liu, X., Wang, Y., & Xiao, J. (2025). Temporo-Spatial Relationship Between Energy Consumption, Air Pollution and Carbon Emissions in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area, China. Sustainability, 17(24), 11175. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411175